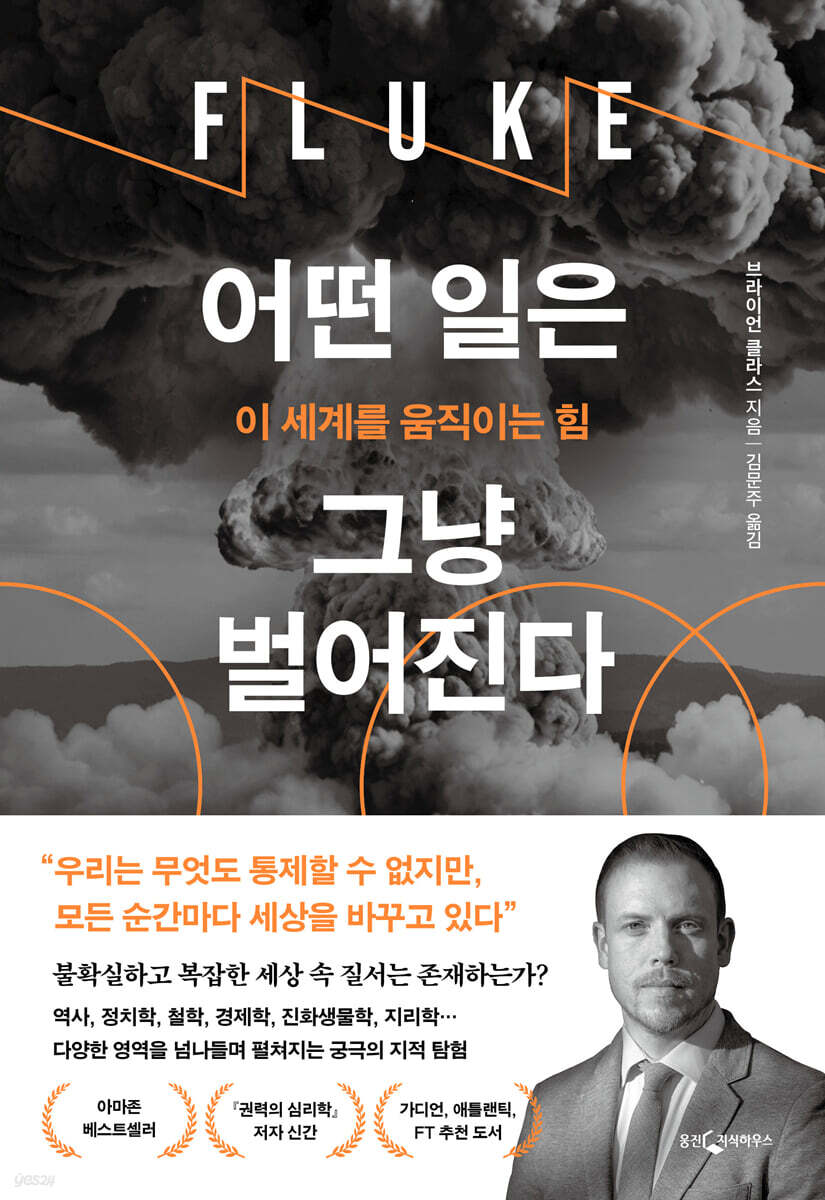

Some things just happen

|

Description

Book Introduction

“The history of mankind is unpredictable.

“It was a series of futile struggles to predict.”

A friendly guide to properly navigating this complex world.

History, political science, philosophy, economics, evolutionary biology, geography…

The ultimate intellectual exploration across diverse fields!

★ Selected as an Amazon Bestseller and Editor's Pick 'Book of the Year' in 2024

★ Recommended books by The Guardian, The Atlantic, and The Financial Times

★ A new book from the author of the social science bestseller, "The Psychology of Power"

If you could go back in time, would everything continue the same? Or would the trajectory of your life be completely altered by the alarm clock you snooze one morning and the bus you miss because of it? People believe that events have a reason, and that by understanding those reasons and identifying patterns, you can control your reality and predict the future.

It is a belief that technological civilization and modern society have bestowed upon us.

But reality completely betrays expectations.

The world is full of contingency and uncertainty.

Brian Klaas, Professor of International Politics at UCL and a prominent social scientist, challenges fundamental assumptions that govern us today and offers a radically new perspective on understanding the world.

This book delves deeply into random coincidences and the profound changes they bring, traversing history and the real world.

Drawing on cutting-edge research from a variety of disciplines, including social science, chaos theory, evolutionary biology, philosophy, and geography, we explore how this complex world actually works.

Furthermore, by breaking the matrix that traps us in the "comfortable lie" of pursuing certainty, it raises profound questions about human free will and how to live a more valuable life.

"Some Things Just Happen," which weaves together compelling case studies and compelling arguments, received rave reviews from leading media outlets and intellectuals, including "A fascinating example of the folly of trying to model and predict an unpredictable world" (Financial Times) and "A fascinating topic that cuts to the heart of everything" (Kirkus Reviews), and became an Amazon bestseller upon its publication.

“It was a series of futile struggles to predict.”

A friendly guide to properly navigating this complex world.

History, political science, philosophy, economics, evolutionary biology, geography…

The ultimate intellectual exploration across diverse fields!

★ Selected as an Amazon Bestseller and Editor's Pick 'Book of the Year' in 2024

★ Recommended books by The Guardian, The Atlantic, and The Financial Times

★ A new book from the author of the social science bestseller, "The Psychology of Power"

If you could go back in time, would everything continue the same? Or would the trajectory of your life be completely altered by the alarm clock you snooze one morning and the bus you miss because of it? People believe that events have a reason, and that by understanding those reasons and identifying patterns, you can control your reality and predict the future.

It is a belief that technological civilization and modern society have bestowed upon us.

But reality completely betrays expectations.

The world is full of contingency and uncertainty.

Brian Klaas, Professor of International Politics at UCL and a prominent social scientist, challenges fundamental assumptions that govern us today and offers a radically new perspective on understanding the world.

This book delves deeply into random coincidences and the profound changes they bring, traversing history and the real world.

Drawing on cutting-edge research from a variety of disciplines, including social science, chaos theory, evolutionary biology, philosophy, and geography, we explore how this complex world actually works.

Furthermore, by breaking the matrix that traps us in the "comfortable lie" of pursuing certainty, it raises profound questions about human free will and how to live a more valuable life.

"Some Things Just Happen," which weaves together compelling case studies and compelling arguments, received rave reviews from leading media outlets and intellectuals, including "A fascinating example of the folly of trying to model and predict an unpredictable world" (Financial Times) and "A fascinating topic that cuts to the heart of everything" (Kirkus Reviews), and became an Amazon bestseller upon its publication.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Chapter 1 Introduction - The Power That Drives Us Through an Uncertain and Complex World

A tourist couple and the life and death of 200,000 people separated by clouds

People who don't want coincidences

A single gesture can change all the constellations.

Some things happen for no reason.

Changing one chapter changes the heat - the illusion of individualism that all actions are independent.

A clock-precise universe vs.

uncertain universe

Small differences can make a huge difference

We live in a world that is far more arbitrary than we think.

Chapter 3: Not Everything Happens for a Reason - How Could Contingency Reign in a World Driven by Probability and Chaos?

We find meaning in the meaningless.

A little twist can change everything

Are we really in control of our own lives?

Why has the role of randomness been overlooked in evolution?

The most surprising developments come from unexpected places.

Chapter 4: Why Our Brains Distort Reality - We Evolved to Over-Detect Patterns

How would history be different if we could only see in black and white?

Our brains are designed to make up stories.

Conspiracy theorists who search for explanations they believe are hidden.

Chapter 5: The Law of the Herd - Every herd stands precariously on the edge of chaos.

A crowd that marches as one and changes direction without warning

A single grain of sand can cause a devastating chain reaction.

The enormous effect of a series of meaningless coincidences

The mirage of regularity

How Ripples Change Lives and Upend Societies

Chapter 6: Heraclitus' Rule - Those Who Mistakenly Think of Controllable Chaos as Controllable Probability

We often mistakenly believe we know the answers to questions we cannot answer.

Can we at least understand ourselves?

It's better to admit you don't know than to use incorrect probabilities.

We get lost when we use probability in areas of uncertainty.

Chapter 7: The Storytelling Animal - The Power of Irrational Beliefs

How do beliefs shape human behavior?

Humans navigate the world through narrative.

There is no beginning, development, climax, and conclusion in reality.

Chapter 8: The Earth Lottery - How do geology and geography shape our destiny and alter our trajectory?

Geography decorates a page of the history we write.

We rarely think about how the Earth shaped us.

Geographic factors change people's choices and shape history.

How do geology, topography, and contingency manifest themselves in reality?

Chapter 9: The Butterfly Effect for Everyone - How Everyone Constantly Changes the World

Each of us flaps our wings a little differently.

History is not what happened, but what we agree happened.

Three discarded cigarettes and the right person who found them.

Sometimes prejudice blinds us and closes our ears.

The important thing is that it is you and no one else who is doing the work.

Chapter 10: Clocks and Calendars - How Can a Brief Moment Change the World?

The contingency of timing endlessly determines and transforms our lives.

We synchronize our lives to the rhythm created by historical events.

Even the same effect can vary greatly depending on the timing.

Chapter 11: The Emperor's New Equation - Why is rocket science easier to understand than human society?

The pitfalls of bad research methods and intentional shortcuts

Was the original theory wrong, or has the world changed?

The problem of strong ties vs.

The problem of weak links

Truthfulness and Mathematics

The Pitfalls of Data Prediction

Chapter 12: Is the world deterministic or indeterministic? - Is life scripted from the start, or do we have the freedom to choose our future?

If I could go back to the beginning of my life, would everything still be the same?

If we leave a little free will, the world will enjoy a comfortable uncertainty.

What is free will?

The paradox of free will

Chapter 13 We Don't Have to Control Everything - The Power of Uncertainty in a Complex and Chaotic World

The despair we created ourselves

A mantra that embraces uncertainty and the unknown: "I don't know."

Everything we do matters

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Introduction - The Power That Drives Us Through an Uncertain and Complex World

A tourist couple and the life and death of 200,000 people separated by clouds

People who don't want coincidences

A single gesture can change all the constellations.

Some things happen for no reason.

Changing one chapter changes the heat - the illusion of individualism that all actions are independent.

A clock-precise universe vs.

uncertain universe

Small differences can make a huge difference

We live in a world that is far more arbitrary than we think.

Chapter 3: Not Everything Happens for a Reason - How Could Contingency Reign in a World Driven by Probability and Chaos?

We find meaning in the meaningless.

A little twist can change everything

Are we really in control of our own lives?

Why has the role of randomness been overlooked in evolution?

The most surprising developments come from unexpected places.

Chapter 4: Why Our Brains Distort Reality - We Evolved to Over-Detect Patterns

How would history be different if we could only see in black and white?

Our brains are designed to make up stories.

Conspiracy theorists who search for explanations they believe are hidden.

Chapter 5: The Law of the Herd - Every herd stands precariously on the edge of chaos.

A crowd that marches as one and changes direction without warning

A single grain of sand can cause a devastating chain reaction.

The enormous effect of a series of meaningless coincidences

The mirage of regularity

How Ripples Change Lives and Upend Societies

Chapter 6: Heraclitus' Rule - Those Who Mistakenly Think of Controllable Chaos as Controllable Probability

We often mistakenly believe we know the answers to questions we cannot answer.

Can we at least understand ourselves?

It's better to admit you don't know than to use incorrect probabilities.

We get lost when we use probability in areas of uncertainty.

Chapter 7: The Storytelling Animal - The Power of Irrational Beliefs

How do beliefs shape human behavior?

Humans navigate the world through narrative.

There is no beginning, development, climax, and conclusion in reality.

Chapter 8: The Earth Lottery - How do geology and geography shape our destiny and alter our trajectory?

Geography decorates a page of the history we write.

We rarely think about how the Earth shaped us.

Geographic factors change people's choices and shape history.

How do geology, topography, and contingency manifest themselves in reality?

Chapter 9: The Butterfly Effect for Everyone - How Everyone Constantly Changes the World

Each of us flaps our wings a little differently.

History is not what happened, but what we agree happened.

Three discarded cigarettes and the right person who found them.

Sometimes prejudice blinds us and closes our ears.

The important thing is that it is you and no one else who is doing the work.

Chapter 10: Clocks and Calendars - How Can a Brief Moment Change the World?

The contingency of timing endlessly determines and transforms our lives.

We synchronize our lives to the rhythm created by historical events.

Even the same effect can vary greatly depending on the timing.

Chapter 11: The Emperor's New Equation - Why is rocket science easier to understand than human society?

The pitfalls of bad research methods and intentional shortcuts

Was the original theory wrong, or has the world changed?

The problem of strong ties vs.

The problem of weak links

Truthfulness and Mathematics

The Pitfalls of Data Prediction

Chapter 12: Is the world deterministic or indeterministic? - Is life scripted from the start, or do we have the freedom to choose our future?

If I could go back to the beginning of my life, would everything still be the same?

If we leave a little free will, the world will enjoy a comfortable uncertainty.

What is free will?

The paradox of free will

Chapter 13 We Don't Have to Control Everything - The Power of Uncertainty in a Complex and Chaotic World

The despair we created ourselves

A mantra that embraces uncertainty and the unknown: "I don't know."

Everything we do matters

Acknowledgements

Detailed image

Into the book

There is a strange disconnect in the way we think about the past compared to the present.

This is also something we need to be careful about when we imagine that we can travel back in time.

The point is that you should never touch anything.

Even a slight change to the past can fundamentally change the world.

You can even accidentally erase your future self.

But we never think that way about the present.

No one is walking around with extreme caution for fear of accidentally crushing a bug.

No one lives in fear that missing the bus once will irrevocably change their future.

Rather, we think that small things are not that important.

It's just that I believe that everything will eventually be washed away and purified.

But if every detail of our past has created our present, then every moment of our present will also create our future.

--- p.22

Imagine if our life were like a movie, where we could rewind to yesterday.

Then, when we return to the beginning of the day, let's change a little detail.

For example, stopping for a moment to drink coffee before running out the front door.

If the day went by pretty much the same whether you drank coffee or not, that would be a convergent event.

The details didn't really matter, what happened was going to happen anyway.

The train of your life left the station a few minutes late, but followed the same track.

But if you stopped for a moment to have a cup of coffee and your future life turned out completely differently, it would be a coincidence.

Because so much can change with just one small detail.

--- p.33

Chaos theory has changed the way we understand the world.

But Lorenz's findings also lead to unsettling questions about our own existence.

What happens to that Tuesday morning resolution to jump out of bed instead of turning off the alarm if a slight shift in wind speed causes a storm a few months later? Are our lives governed by seemingly random misfortunes and luck, including trivial choices? And this raises a perplexing question:

If Henry Stimson's vacation plans in 1926 could affect the lives of hundreds of thousands of people living thousands of miles away 20 years later, it's not just our alarm clocks we should be worried about.

Even the seemingly insignificant choices of 8 billion people, like alarm clocks, can shake up the trajectory of our lives.

This is true even if we are not aware of the fact.

--- p.54

It now becomes clear that our existence and the way we live are contingent, arbitrary, and therefore unstable.

Scientists have even discovered that the reason we don't lay eggs dates back to a retrovirus infection in a shrew-like creature about 100 million years ago.

This led to the evolution of the placenta and ultimately the process of childbirth.

The story of our lives is written through the intricate collaboration of countless authors, human and non-human, stretching back across vast distances to the distant past.

But if it hadn't been for a single, coincidental event that occurred over a period of time so long forgotten that it's almost dim, we wouldn't exist.

--- p.74

We spend a lot of time trying to create explanations when none are immediately available.

For example, at the end of World War I, the blood-soaked trenches were filled not only with corpses but also with amulets.

Branches of heather, heart-shaped amulets, and rabbit's feet were buried together in makeshift graves.

Troops descending from the mountains of the Austro-Hungarian Empire believed that sewing bat wings into their underwear would save their lives.

No one would dare wear a dead person's boots, no matter how high-quality the leather they were made of.

Twenty years later, another world war broke out, and superstitions multiplied again.

As the flying bombs began to fall on London in 1944, residents developed maps and superstitions to combat them, frantically trying to predict where the next blast would land.

However, after the war, analysis of the blast area revealed that the destruction followed a Poisson distribution, almost completely randomly distributed.

--- p.119

Complex systems, such as a swarm of locusts or a modern human society, contain diverse, interacting, and interconnected parts (or individuals) that adapt to one another.

Like our world, this system undergoes constant change.

When you change one aspect of a system, other parts naturally adjust, creating something entirely new.

When you hit the brakes while driving, or when someone in a crowd stops to talk to someone else, people don't just keep moving; they follow a modified trajectory.

They adapt and adjust.

The entire flow of people or vehicles within a system can be drastically affected by a single small change.

--- p.143

Many problems can arise when we try to master complex systems.

China under Mao Zedong learned this the hard way.

Mao Zedong failed to understand that nature's ecology is complex, and that some species are untamable and susceptible to change.

The Chinese dictator promoted a sacrificial rite movement, ordering his people to kill rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows.

He hoped this would help eradicate human disease.

But once the sparrows were eradicated, the locusts no longer had to face any natural predators.

This caused unexpected ecological chaos as swarms of locusts overran the area.

A famine occurred and 55 million people lost their lives.

--- p.152

More than a century after World War I, big data, analytics, and machine learning are enabling unprecedented accuracy in predicting the average behavior of crowds within seemingly stable systems.

For example, in the UK, the power grid is now managed to account for "TV pick-up," which occurs when millions of people watching a World Cup match on TV simultaneously turn on their kettles during halftime.

Data-driven predictions of power needs are often incredibly, even frighteningly, accurate.

We can predict the collective actions of millions of people more accurately than ever before.

This gives us a sense of pride that we have conquered the world.

The so-called illusion of control is the illusion of control.

--- p.157

However, in the 18th century, Scottish philosopher David Hume raised the famous 'problem of induction', warning that probability is far from certainty.

Hume's warning was sharp.

Hume said that most of our knowledge of causality is based on experience, that is, on what happened in the past.

He also emphasized that there is no guarantee that the future will be like the past.

Or, more charmingly, say this:

“Probability is based on estimating the similarity between the past and the future.

“It is the similarity between something we have already experienced and something we have no experience with.” Probability can be useful.

But the future may differ from the patterns of the past, and when it does, it will be a challenge for us (as we will see, Hume was right).

--- p.169

Why did this happen? Part of the explanation lies in the fact that we are cognitive victims of our own remarkable success.

Scientists are the wizards of the modern age.

Manipulate genes, discover nearly invisible particles, and even change the direction of asteroids.

These breakthroughs gave us the valid but misleading feeling that we were close to unlocking the world's mysteries.

Too many people believe that human knowledge is in the final stages of development and that this vexing, unexplored problem will soon be neatly resolved and a satisfactory answer will be given.

For example, there is no cure for cancer yet, but one will be available soon, or Mars is not inhabitable yet, but people will soon.

Modern science, which seems to know everything, seems to protect us from the dangers of contingency and chaos.

--- p.170~171

In 2016, The Economist analyzed the IMF's economic forecasts for 189 countries, covering roughly 15 years.

During this period, the country entered into 220 economic recessions, a major economic downturn that seriously affected millions of people.

Each year, the IMF releases its economic forecasts twice: once in April and once in October after looking at actual data for six months.

How many times will this prediction accurately pinpoint the onset of an economic downturn? How many times will the greatest minds of our time get it right? Of the 220 recessions predicted in April, not a single one was correct, resulting in a zero-hit rate.

These predictions never saw the coming future.

October's forecasts provided real-world data with warning signs to address, but only half of them were understood.

--- p.174

Most professional studies of humanity emerge from how people experience the world.

84 percent of the world's population identifies with a religious group.

In a Pew Research survey conducted in 34 countries, two out of three people agreed that “God plays an important role in my life.”

A 2022 study of 95 countries found that about 40 percent of the world's population believed in witchcraft, which is defined as "the ability to intentionally cause harm through supernatural means."

Trying to understand politics without a clear understanding of how beliefs shape human behavior is like trying to drive a car without a steering wheel.

Faith is an important human element that should not be ignored.

However, some branches of rational choice models and game theory still ignore this.

In the real world, emotions, intuition, impulses, beliefs and faith in God ultimately fundamentally influence important decisions.

But we assume that this world is filled with people who are like potential probability calculators.

--- p.206

Our beliefs are most easily influenced when we inject ideas into a story.

Since the beginning of time, humanity has accumulated wisdom to understand this world over time.

How could this wisdom be passed down across generations? Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio answers:

“I was faced with the problem of how to understand, disseminate, persuade, and enforce all this wisdom, and how to maintain it, and I found a solution.

Storytelling was the solution.” Our brains are so accustomed to narrative that they can connect the dots and create a story even when there are no lines between them.

This is called narrative bias.

When we are given a piece of incomplete information, the networks in our brain that process patterns fill in the gaps.

--- p.208

Today, to make arguments that rely on 'geographic determinism' or 'environmental determinism' is a serious insult to history and the social sciences, and a way of immediately dismissing scholarly arguments.

It's no wonder that the notion that geography determines outcomes has been used to justify racism for thousands of years.

In ancient China, a judge named Guan Zhong claimed that people living near fast-flowing, winding rivers were inevitably “greedy, rude, and warlike.”

In ancient Greece, Hippocrates, the father of medicine, even deduced that Scythian men must have suffered from erectile dysfunction, given that they lived in a harsh land.

Ibn Khaldun, a 14th-century Arab scholar and the father of social science, argued that darker skin tones were caused by hotter weather and that environment determined whether a people were nomadic or settled.

Centuries later, these theories influenced the French historian and political philosopher Montesquieu, who returned to climate-based theories that placed Europeans at the top of the racial hierarchy.

Geographic racism, in turn, became enshrined in the pantheon of intellectually bankrupt concepts used by white oppressors to justify colonialism.

--- p.229

This becomes more clear when we consider the following thought experiment.

Imagine an Earth without humans.

Then, through some magic, three groups of humans are dropped somewhere on the vast continent of Earth and start a new civilization.

But where it lands is completely random.

One group lands in the Loire Valley in France.

It is a place with abundant water, fertile land, and a mild and wonderful climate.

Another group lands in the Australian outback.

The third group, unfortunately, ends up spending their short lives in Antarctica.

Clearly, topography, geology, and climate will determine the fate of the herd to some extent.

The notion that geography influences human trajectories and inequalities does not, in any way, negate the importance of history, decision-making, culture, or the atrocities committed in more traditional historical narratives.

--- p.235

“All models are wrong, but some are useful,” said statistician George Box.

We too often forget this lesson, conflating maps and regions, and mistakenly assuming that a simplified representation of the world accurately depicts the world.

How often have you heard statements like "according to new predictions" or "recent research has found" and simply accepted them without examining the underlying assumptions or methodology? Social research is one of the best tools for navigating an uncertain world, and sometimes it can be incredibly helpful.

But if we want to avoid the often disastrous mistakes that often occur, we need to become more aware of what we can and cannot understand about ourselves as we navigate this complex world, shaken by randomness, accident, and haphazardness.

It's time to be honest about how little we know for sure.

We need to take a quick look into the world of social research and see the ugly truth for ourselves.

--- p.295

Essayist Maria Popova enlightens us:

"Living in awe of reality is the most joyful way to live." How many of us are trapped in the hamster wheel of modern life, plodding along, indifferent? It's time to let go of the false idols of mastery and control, and, if we know where to look, marvel at the beauty hidden within uncertainty.

--- p.366

In the mid-1990s, Catalin Kariko believed her research had promise, so she applied for grants again and again.

She was rejected again and again and failed.

Venture capitalists even considered her idea a waste of money.

After these repeated failures, Kariko's university issued an ultimatum.

Quit or get demoted.

Kariko kept holding on, and we are grateful that Kariko kept holding on.

Thanks to Kariko's research on mRNA, millions of lives could soon be saved.

This is the basis for developing the most effective coronavirus vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This research was not useful until the world suddenly changed.

But now it has become one of the most useful scientific discoveries in history.

Kariko won the Nobel Prize.

This is also something we need to be careful about when we imagine that we can travel back in time.

The point is that you should never touch anything.

Even a slight change to the past can fundamentally change the world.

You can even accidentally erase your future self.

But we never think that way about the present.

No one is walking around with extreme caution for fear of accidentally crushing a bug.

No one lives in fear that missing the bus once will irrevocably change their future.

Rather, we think that small things are not that important.

It's just that I believe that everything will eventually be washed away and purified.

But if every detail of our past has created our present, then every moment of our present will also create our future.

--- p.22

Imagine if our life were like a movie, where we could rewind to yesterday.

Then, when we return to the beginning of the day, let's change a little detail.

For example, stopping for a moment to drink coffee before running out the front door.

If the day went by pretty much the same whether you drank coffee or not, that would be a convergent event.

The details didn't really matter, what happened was going to happen anyway.

The train of your life left the station a few minutes late, but followed the same track.

But if you stopped for a moment to have a cup of coffee and your future life turned out completely differently, it would be a coincidence.

Because so much can change with just one small detail.

--- p.33

Chaos theory has changed the way we understand the world.

But Lorenz's findings also lead to unsettling questions about our own existence.

What happens to that Tuesday morning resolution to jump out of bed instead of turning off the alarm if a slight shift in wind speed causes a storm a few months later? Are our lives governed by seemingly random misfortunes and luck, including trivial choices? And this raises a perplexing question:

If Henry Stimson's vacation plans in 1926 could affect the lives of hundreds of thousands of people living thousands of miles away 20 years later, it's not just our alarm clocks we should be worried about.

Even the seemingly insignificant choices of 8 billion people, like alarm clocks, can shake up the trajectory of our lives.

This is true even if we are not aware of the fact.

--- p.54

It now becomes clear that our existence and the way we live are contingent, arbitrary, and therefore unstable.

Scientists have even discovered that the reason we don't lay eggs dates back to a retrovirus infection in a shrew-like creature about 100 million years ago.

This led to the evolution of the placenta and ultimately the process of childbirth.

The story of our lives is written through the intricate collaboration of countless authors, human and non-human, stretching back across vast distances to the distant past.

But if it hadn't been for a single, coincidental event that occurred over a period of time so long forgotten that it's almost dim, we wouldn't exist.

--- p.74

We spend a lot of time trying to create explanations when none are immediately available.

For example, at the end of World War I, the blood-soaked trenches were filled not only with corpses but also with amulets.

Branches of heather, heart-shaped amulets, and rabbit's feet were buried together in makeshift graves.

Troops descending from the mountains of the Austro-Hungarian Empire believed that sewing bat wings into their underwear would save their lives.

No one would dare wear a dead person's boots, no matter how high-quality the leather they were made of.

Twenty years later, another world war broke out, and superstitions multiplied again.

As the flying bombs began to fall on London in 1944, residents developed maps and superstitions to combat them, frantically trying to predict where the next blast would land.

However, after the war, analysis of the blast area revealed that the destruction followed a Poisson distribution, almost completely randomly distributed.

--- p.119

Complex systems, such as a swarm of locusts or a modern human society, contain diverse, interacting, and interconnected parts (or individuals) that adapt to one another.

Like our world, this system undergoes constant change.

When you change one aspect of a system, other parts naturally adjust, creating something entirely new.

When you hit the brakes while driving, or when someone in a crowd stops to talk to someone else, people don't just keep moving; they follow a modified trajectory.

They adapt and adjust.

The entire flow of people or vehicles within a system can be drastically affected by a single small change.

--- p.143

Many problems can arise when we try to master complex systems.

China under Mao Zedong learned this the hard way.

Mao Zedong failed to understand that nature's ecology is complex, and that some species are untamable and susceptible to change.

The Chinese dictator promoted a sacrificial rite movement, ordering his people to kill rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows.

He hoped this would help eradicate human disease.

But once the sparrows were eradicated, the locusts no longer had to face any natural predators.

This caused unexpected ecological chaos as swarms of locusts overran the area.

A famine occurred and 55 million people lost their lives.

--- p.152

More than a century after World War I, big data, analytics, and machine learning are enabling unprecedented accuracy in predicting the average behavior of crowds within seemingly stable systems.

For example, in the UK, the power grid is now managed to account for "TV pick-up," which occurs when millions of people watching a World Cup match on TV simultaneously turn on their kettles during halftime.

Data-driven predictions of power needs are often incredibly, even frighteningly, accurate.

We can predict the collective actions of millions of people more accurately than ever before.

This gives us a sense of pride that we have conquered the world.

The so-called illusion of control is the illusion of control.

--- p.157

However, in the 18th century, Scottish philosopher David Hume raised the famous 'problem of induction', warning that probability is far from certainty.

Hume's warning was sharp.

Hume said that most of our knowledge of causality is based on experience, that is, on what happened in the past.

He also emphasized that there is no guarantee that the future will be like the past.

Or, more charmingly, say this:

“Probability is based on estimating the similarity between the past and the future.

“It is the similarity between something we have already experienced and something we have no experience with.” Probability can be useful.

But the future may differ from the patterns of the past, and when it does, it will be a challenge for us (as we will see, Hume was right).

--- p.169

Why did this happen? Part of the explanation lies in the fact that we are cognitive victims of our own remarkable success.

Scientists are the wizards of the modern age.

Manipulate genes, discover nearly invisible particles, and even change the direction of asteroids.

These breakthroughs gave us the valid but misleading feeling that we were close to unlocking the world's mysteries.

Too many people believe that human knowledge is in the final stages of development and that this vexing, unexplored problem will soon be neatly resolved and a satisfactory answer will be given.

For example, there is no cure for cancer yet, but one will be available soon, or Mars is not inhabitable yet, but people will soon.

Modern science, which seems to know everything, seems to protect us from the dangers of contingency and chaos.

--- p.170~171

In 2016, The Economist analyzed the IMF's economic forecasts for 189 countries, covering roughly 15 years.

During this period, the country entered into 220 economic recessions, a major economic downturn that seriously affected millions of people.

Each year, the IMF releases its economic forecasts twice: once in April and once in October after looking at actual data for six months.

How many times will this prediction accurately pinpoint the onset of an economic downturn? How many times will the greatest minds of our time get it right? Of the 220 recessions predicted in April, not a single one was correct, resulting in a zero-hit rate.

These predictions never saw the coming future.

October's forecasts provided real-world data with warning signs to address, but only half of them were understood.

--- p.174

Most professional studies of humanity emerge from how people experience the world.

84 percent of the world's population identifies with a religious group.

In a Pew Research survey conducted in 34 countries, two out of three people agreed that “God plays an important role in my life.”

A 2022 study of 95 countries found that about 40 percent of the world's population believed in witchcraft, which is defined as "the ability to intentionally cause harm through supernatural means."

Trying to understand politics without a clear understanding of how beliefs shape human behavior is like trying to drive a car without a steering wheel.

Faith is an important human element that should not be ignored.

However, some branches of rational choice models and game theory still ignore this.

In the real world, emotions, intuition, impulses, beliefs and faith in God ultimately fundamentally influence important decisions.

But we assume that this world is filled with people who are like potential probability calculators.

--- p.206

Our beliefs are most easily influenced when we inject ideas into a story.

Since the beginning of time, humanity has accumulated wisdom to understand this world over time.

How could this wisdom be passed down across generations? Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio answers:

“I was faced with the problem of how to understand, disseminate, persuade, and enforce all this wisdom, and how to maintain it, and I found a solution.

Storytelling was the solution.” Our brains are so accustomed to narrative that they can connect the dots and create a story even when there are no lines between them.

This is called narrative bias.

When we are given a piece of incomplete information, the networks in our brain that process patterns fill in the gaps.

--- p.208

Today, to make arguments that rely on 'geographic determinism' or 'environmental determinism' is a serious insult to history and the social sciences, and a way of immediately dismissing scholarly arguments.

It's no wonder that the notion that geography determines outcomes has been used to justify racism for thousands of years.

In ancient China, a judge named Guan Zhong claimed that people living near fast-flowing, winding rivers were inevitably “greedy, rude, and warlike.”

In ancient Greece, Hippocrates, the father of medicine, even deduced that Scythian men must have suffered from erectile dysfunction, given that they lived in a harsh land.

Ibn Khaldun, a 14th-century Arab scholar and the father of social science, argued that darker skin tones were caused by hotter weather and that environment determined whether a people were nomadic or settled.

Centuries later, these theories influenced the French historian and political philosopher Montesquieu, who returned to climate-based theories that placed Europeans at the top of the racial hierarchy.

Geographic racism, in turn, became enshrined in the pantheon of intellectually bankrupt concepts used by white oppressors to justify colonialism.

--- p.229

This becomes more clear when we consider the following thought experiment.

Imagine an Earth without humans.

Then, through some magic, three groups of humans are dropped somewhere on the vast continent of Earth and start a new civilization.

But where it lands is completely random.

One group lands in the Loire Valley in France.

It is a place with abundant water, fertile land, and a mild and wonderful climate.

Another group lands in the Australian outback.

The third group, unfortunately, ends up spending their short lives in Antarctica.

Clearly, topography, geology, and climate will determine the fate of the herd to some extent.

The notion that geography influences human trajectories and inequalities does not, in any way, negate the importance of history, decision-making, culture, or the atrocities committed in more traditional historical narratives.

--- p.235

“All models are wrong, but some are useful,” said statistician George Box.

We too often forget this lesson, conflating maps and regions, and mistakenly assuming that a simplified representation of the world accurately depicts the world.

How often have you heard statements like "according to new predictions" or "recent research has found" and simply accepted them without examining the underlying assumptions or methodology? Social research is one of the best tools for navigating an uncertain world, and sometimes it can be incredibly helpful.

But if we want to avoid the often disastrous mistakes that often occur, we need to become more aware of what we can and cannot understand about ourselves as we navigate this complex world, shaken by randomness, accident, and haphazardness.

It's time to be honest about how little we know for sure.

We need to take a quick look into the world of social research and see the ugly truth for ourselves.

--- p.295

Essayist Maria Popova enlightens us:

"Living in awe of reality is the most joyful way to live." How many of us are trapped in the hamster wheel of modern life, plodding along, indifferent? It's time to let go of the false idols of mastery and control, and, if we know where to look, marvel at the beauty hidden within uncertainty.

--- p.366

In the mid-1990s, Catalin Kariko believed her research had promise, so she applied for grants again and again.

She was rejected again and again and failed.

Venture capitalists even considered her idea a waste of money.

After these repeated failures, Kariko's university issued an ultimatum.

Quit or get demoted.

Kariko kept holding on, and we are grateful that Kariko kept holding on.

Thanks to Kariko's research on mRNA, millions of lives could soon be saved.

This is the basis for developing the most effective coronavirus vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This research was not useful until the world suddenly changed.

But now it has become one of the most useful scientific discoveries in history.

Kariko won the Nobel Prize.

--- p.384~385

Publisher's Review

“Why We Make the Error of Believing in ‘False Certainty’”

History, political science, philosophy, economics, evolutionary biology, geography…

A complex world explored across various academic fields

- Why was the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima and not on Kyoto, where the munitions factory was located?

- How did a scholar studying weather forecasting come up with chaos theory?

- How many times has the IMF's economic forecast been accurate?

- Was World War I predictable?

- Was human evolution an inevitable function of genes?

The reason the American atomic bomb 'Little Boy' was dropped on Hiroshima, not Kyoto, which was its original target, was because it was a city of affection for an officer couple who had traveled there long ago.

Chaos theory was born out of nowhere when a scientist studying weather forecasting noticed small changes occurring in subsets.

The Archduke of Austria-Hungary, who narrowly escaped death in a hunting ground, was assassinated, sparking World War I, and the IMF repeatedly failed to predict the recession.

Humanity has believed that there is a proper cause for any great event or discovery and that statistics and probability can be used to predict the future.

But the more we dig into the cause, the more our expectations are overturned and our predictions are likely to go wrong time and time again.

The world has completely betrayed the belief that 'everything happens for a reason' and has reached its current state through a chain of accidental events.

Yet, we are forced to choose comfort between 'complex uncertainty' and the comforting but 'false certainty'.

This book shatters that solid but flawed conviction.

The world is at the 'edge of chaos', a crossroads between complete chaos and order.

The author delves into the workings of this complex world, examining the results of uncontrollable, random, and coincidental events based on research findings from various disciplines.

“We live in a world that is more random and arbitrary than we think.”

Some things happen for no reason

A butterfly's flapping wings can cause a hurricane.

There was a woman a long time ago who killed all of her children and then took her own life.

It was a horrific incident that was featured in the local newspaper.

The woman's husband remarried and had another child.

The husband in the incident is the great-grandfather of the author of this book, Brian Klass.

What if someone had intervened? Some people's lives would have continued, but the author would no longer exist.

The book begins with a mystery of coincidence and chaos captured in the author's own personal history.

The author further raises the question of human history as “a process of constant but futile struggle to bring order, certainty, and rationality to the world.”

For so long, we have been so caught up in the delusion that scientific advancements and innovations sufficiently reveal the workings of the world that we have turned a blind eye to the "inevitable coincidence."

But the world is more violent and unruly than we think, and even the slightest flap of a butterfly's wings can send huge ripples.

Because of this uncertainty, we can never know future outcomes, nor the underlying mechanisms that produce them.

Brian Klaas challenges the fundamental assumptions that govern us today and offers a whole new way of understanding the world.

It delves deeply into random coincidences and the enormous changes they bring, traversing history and the real world.

It reinforces the argument that some things just happen for no reason, while also emphasizing the meaning this book conveys.

“By accepting that we and all the circumstances around us are simply chance, thrown by an untamable universe, we can learn to face the messiness and uncertainty of reality and find new meaning in this chaos.”

“We control nothing, but we influence everything.”

This wonderful and maddeningly complex world

Why You Should Explore with an Open Mind

The author of this book, Brian Klaas, a professor of international politics at UCL, is a political consultant who has advised various government agencies, NATO, the EU, and NGOs.

He has emerged as a social scientist who has been receiving attention from various media outlets and major news outlets, particularly for his sharp analysis of the nature of power and systems.

This time, we return to a deeper insight into how the world works, beyond political science.

"Some Things Just Happen," which weaves together a wide range of research and fascinating case studies from psychology, anthropology, evolutionary biology, philosophy, and social science, became an Amazon bestseller upon its publication.

It has been praised by leading media and intellectuals, including “a fascinating example of the folly of trying to model and predict an unpredictable world” (Financial Times), “a fascinating topic that penetrates the essence of everything” (Kirkus Review), and “a mind-bogglingly intelligent book” (Jonathan Gottschall).

Encompassing diverse histories, vast archives, and research, and exploring a world dominated by chance and chaos, the book's ultimate goal is to "weave these pieces together to create a new, coherent picture that reconstructs our notions of who we are and how our world works."

This book does not stop at persuasively depicting the history of mankind's 'vain predictions'.

It pushes away “the despair created by the vain desire for control” and forces us to accept that “we are contingency in the universe, connected atoms imbued with consciousness, drifting in a sea of uncertainty.”

Furthermore, it emphasizes that all the beings that make up the world are interconnected, so every choice and action we make is important.

Only when we realize that “we control nothing, but we influence everything” do we gain the freedom to truly see, explore, and expand the world.

History, political science, philosophy, economics, evolutionary biology, geography…

A complex world explored across various academic fields

- Why was the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima and not on Kyoto, where the munitions factory was located?

- How did a scholar studying weather forecasting come up with chaos theory?

- How many times has the IMF's economic forecast been accurate?

- Was World War I predictable?

- Was human evolution an inevitable function of genes?

The reason the American atomic bomb 'Little Boy' was dropped on Hiroshima, not Kyoto, which was its original target, was because it was a city of affection for an officer couple who had traveled there long ago.

Chaos theory was born out of nowhere when a scientist studying weather forecasting noticed small changes occurring in subsets.

The Archduke of Austria-Hungary, who narrowly escaped death in a hunting ground, was assassinated, sparking World War I, and the IMF repeatedly failed to predict the recession.

Humanity has believed that there is a proper cause for any great event or discovery and that statistics and probability can be used to predict the future.

But the more we dig into the cause, the more our expectations are overturned and our predictions are likely to go wrong time and time again.

The world has completely betrayed the belief that 'everything happens for a reason' and has reached its current state through a chain of accidental events.

Yet, we are forced to choose comfort between 'complex uncertainty' and the comforting but 'false certainty'.

This book shatters that solid but flawed conviction.

The world is at the 'edge of chaos', a crossroads between complete chaos and order.

The author delves into the workings of this complex world, examining the results of uncontrollable, random, and coincidental events based on research findings from various disciplines.

“We live in a world that is more random and arbitrary than we think.”

Some things happen for no reason

A butterfly's flapping wings can cause a hurricane.

There was a woman a long time ago who killed all of her children and then took her own life.

It was a horrific incident that was featured in the local newspaper.

The woman's husband remarried and had another child.

The husband in the incident is the great-grandfather of the author of this book, Brian Klass.

What if someone had intervened? Some people's lives would have continued, but the author would no longer exist.

The book begins with a mystery of coincidence and chaos captured in the author's own personal history.

The author further raises the question of human history as “a process of constant but futile struggle to bring order, certainty, and rationality to the world.”

For so long, we have been so caught up in the delusion that scientific advancements and innovations sufficiently reveal the workings of the world that we have turned a blind eye to the "inevitable coincidence."

But the world is more violent and unruly than we think, and even the slightest flap of a butterfly's wings can send huge ripples.

Because of this uncertainty, we can never know future outcomes, nor the underlying mechanisms that produce them.

Brian Klaas challenges the fundamental assumptions that govern us today and offers a whole new way of understanding the world.

It delves deeply into random coincidences and the enormous changes they bring, traversing history and the real world.

It reinforces the argument that some things just happen for no reason, while also emphasizing the meaning this book conveys.

“By accepting that we and all the circumstances around us are simply chance, thrown by an untamable universe, we can learn to face the messiness and uncertainty of reality and find new meaning in this chaos.”

“We control nothing, but we influence everything.”

This wonderful and maddeningly complex world

Why You Should Explore with an Open Mind

The author of this book, Brian Klaas, a professor of international politics at UCL, is a political consultant who has advised various government agencies, NATO, the EU, and NGOs.

He has emerged as a social scientist who has been receiving attention from various media outlets and major news outlets, particularly for his sharp analysis of the nature of power and systems.

This time, we return to a deeper insight into how the world works, beyond political science.

"Some Things Just Happen," which weaves together a wide range of research and fascinating case studies from psychology, anthropology, evolutionary biology, philosophy, and social science, became an Amazon bestseller upon its publication.

It has been praised by leading media and intellectuals, including “a fascinating example of the folly of trying to model and predict an unpredictable world” (Financial Times), “a fascinating topic that penetrates the essence of everything” (Kirkus Review), and “a mind-bogglingly intelligent book” (Jonathan Gottschall).

Encompassing diverse histories, vast archives, and research, and exploring a world dominated by chance and chaos, the book's ultimate goal is to "weave these pieces together to create a new, coherent picture that reconstructs our notions of who we are and how our world works."

This book does not stop at persuasively depicting the history of mankind's 'vain predictions'.

It pushes away “the despair created by the vain desire for control” and forces us to accept that “we are contingency in the universe, connected atoms imbued with consciousness, drifting in a sea of uncertainty.”

Furthermore, it emphasizes that all the beings that make up the world are interconnected, so every choice and action we make is important.

Only when we realize that “we control nothing, but we influence everything” do we gain the freedom to truly see, explore, and expand the world.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 27, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 420 pages | 736g | 150*218*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788901287171

- ISBN10: 890128717X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)