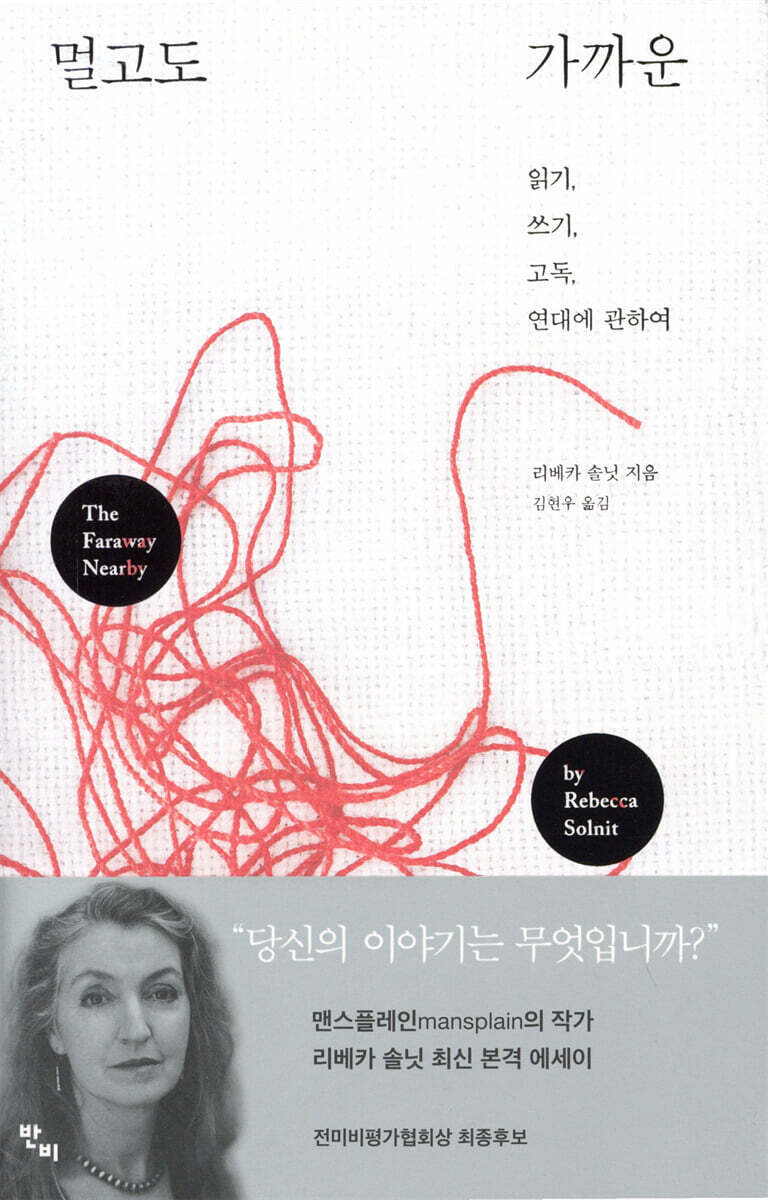

Far yet close

|

Description

Book Introduction

Rebecca Solnit's new book, selected by Uton Leader as one of the "25 Thinkers Who Will Change the World," is a must-read.

National Book Award nominee, National Book Critics Circle Award finalist

“What is your story?”

Connecting you and me,

The power of stories to help us overcome life's challenges

A new book by Rebecca Solnit, the author best known for coining the term 'mansplaining.'

Essays on reading and writing, solitude and solidarity, illness and care, life and death, mothers and daughters, Iceland and the Arctic.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, C.

From S. Lewis's 'The Chronicles of Narnia', Freucen's 'The Polar Adventure', Che Guevara's 'The Motorcycle Diaries', and fairy tales like 'The Swan Prince' and 'Lumpenstiltsken', we use a variety of stories to observe and understand the complexly intertwined lives of the authors.

We take a close look at the role stories play in shaping our lives and relationships.

It's an intimate memoir, but it's also a unique essay that only Rebecca Solnit could write, eloquently exploring the public effects of reading and writing.

National Book Award nominee, National Book Critics Circle Award finalist

“What is your story?”

Connecting you and me,

The power of stories to help us overcome life's challenges

A new book by Rebecca Solnit, the author best known for coining the term 'mansplaining.'

Essays on reading and writing, solitude and solidarity, illness and care, life and death, mothers and daughters, Iceland and the Arctic.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, C.

From S. Lewis's 'The Chronicles of Narnia', Freucen's 'The Polar Adventure', Che Guevara's 'The Motorcycle Diaries', and fairy tales like 'The Swan Prince' and 'Lumpenstiltsken', we use a variety of stories to observe and understand the complexly intertwined lives of the authors.

We take a close look at the role stories play in shaping our lives and relationships.

It's an intimate memoir, but it's also a unique essay that only Rebecca Solnit could write, eloquently exploring the public effects of reading and writing.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Apricot / Mirror / Ice / Flight / Breath / Wrap / Knot / Untie / Breath / Flight / Ice / Mirror / Apricot

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

Publisher's Review

“What is your story?”

The power of stories that connect you and me and help us overcome life's challenges.

“I believe in the power of a larger story to cleanse the poison of a bad story and ultimately flow into a river of beautiful stories.

“Solnit is a warrior of storytelling who fights and ultimately wins against the spell of bad stories imposed on her by creating more powerful stories.” Jeong Yeo-ul (literary critic)

“This is the most specific proverb I have ever read.

There is not a single phrase floating in the air.

Only working women can write such things.

Intelligence and insight are powers that only the weak can possess.

It's true that reading eases the pain of life.

It also calms loneliness and the desire to die.

“I believe that we can connect just by reading.” Jeong Hee-jin (author of “Reading Like Jeong Hee-jin”)

A full-fledged essay that delves into the essence of Rebecca Solnit, author of "Mansplaining."

"Far and Near" is Rebecca Solnit's new book and a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Solnit gained fame in 2010 when she used the word "mansplaining" in a column to lucidly summarize the core of gender inequality that persists even in the 21st century.

This word was selected as the New York Times' '2010 Word of the Year', and Solnit was selected as one of the '25 Thinkers Who Will Change the World' by Utton Reader in the same year.

In 2015, the word "mansplaining" was added to the online version of the Oxford English Dictionary, and the column collection "Men Keep Trying to Teach Me Lessons" containing this article was introduced in Korea and selected as the book of the year by most media outlets.

In addition to this book, there are other books introduced in Korea that show the author's diverse interests and aspects, such as 『History of Walking』, 『Gaze at These Ruins』, and 『Hope in the Darkness』. In particular, 『Far and Near』 is significant in that it is a full-fledged work that most comprehensively shows such diverse aspects.

The book's main themes are reading and writing, solitude and solidarity, illness and care, life and death, mothers and daughters, Iceland and the Arctic.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, C.

Solnit uses a variety of stories, including S. Lewis's 'The Chronicles of Narnia', Freucen's 'The Polar Adventure', Che Guevara's 'The Motorcycle Diaries', and oral fairy tales such as 'The Swan Prince', 'Lumpenstiltskin', and 'The Snow Queen', to observe, think about, and ultimately understand the lives around her.

It is a different kind of understanding than making excuses for someone, covering up someone's mistakes, or showing off the writer's superiority.

The author calls this forgiveness and love.

With this warm and objective perspective, the author meticulously observes the role stories play in shaping our lives and relationships.

It is a unique essay, a memoir of intimacy, yet also eloquently about the public effects of reading and writing, a work that only Solnit could write.

What's your story? The power of stories that make us who we are.

The overarching theme that ties together the diverse topics of this book is the power of storytelling.

We weave stories to form our identity.

As Solnit says, the self is an important work of art that our lives create, and it is the work that turns everyone into an artist.

For example, many fairy tales deal with problem solving, and the protagonists of fairy tales become 'themselves' in the process of solving the problem.

This is a basic principle of storytelling.

A story is a process of discovering who we are, and in the process, with the help of others, we become aware of our limitations, overcome them, and become someone else.

Our stories are only possible by constantly encountering other people's stories along the way.

This also means that the ability to ‘listen’ and ‘read’, as well as the ability to empathize with and understand others, are fundamentally necessary in creating a ‘self’.

The book calls up countless stories, including classics like Frankenstein and archetypal narratives like The Swan Prince, as well as the story of an Eskimo woman who survived the extreme cold by eating the corpses of her husband and child, the story of a firefighter who saved a girl who fell into a well in front of the world on TV and then committed suicide as a result, the story of a polar bear that eats a polar bear that looks just like itself, and above all, the story of Solnit's mother, which could be called a darker version of Cinderella.

Understanding how these stories transformed Solnit can, in turn, influence our own lives.

This book, Solnit's story, transcends physical distance and firmly connects her life with ours.

In fairy tales, power itself is rarely a suitable means of survival.

Rather, it is often the powerless who unite and achieve success, often through acts of kindness toward one another.

Those who repay this deed are the ones who leave the beehive unbroken, the birds released without killing them, and the old women who welcome us with respect.

Kindness sown like a seed to a weak being bears fruit in a fairy tale, and sometimes even in reality, in moments of crisis. (28)

Like many who become writers, I too have been lost in books since childhood.

He disappeared into it as if he was running into the forest.

What surprised me, and still surprises me, is that beyond the forest of stories and solitude, there is a place, and if you go out there, you can meet people.

Writers are, and need to be, isolated by the nature of their profession.

Sometimes I think talent isn't the issue.

A writer's talent is not as rare as people think.

Rather, that talent is partly revealed in the ability to endure long periods of solitude and continue working.

Before being a writer, a writer is a reader, and he lives in and across books.

To live in another's life, and also in another's head, in that act which is deeply intimate, yet also utterly lonely. (96)

What we call a book is not a real book, but the potential it holds, like a musical score or a seed.

A book exists only when it is read, and its true home is in the reader's head, where the orchestra resonates and the seeds germinate.

A book is a heart that beats only in another person's body. (100)

Writing is an act of saying to no one what one cannot say to anyone, while at the same time saying to everyone what one cannot say to anyone.

Or, it is an act of telling a story that cannot be told to anyone now, to someone who may become a reader in the future.

You discover that you can write down and share with strangers stories so sensitive, so personal, so nebulous that you would normally never imagine telling even the closest of people, words that would otherwise escape the ears of others.

Writing speaks to a complete stranger in silence, and the story finds its voice and resonates through solitary reading.

Isn't that the loneliness shared through writing?

Footprints were clearly imprinted on the hard, damp sand at low tide.

It would remain like that until the tide came in again and completely erased the traces of its passage.

I love looking at the long line we each leave behind.

Sometimes I imagine my life that way.

As if each step were a stitch in a needle, as if I were a needle and the world was being sewn along the path I took with each step I took.

Although they intersect with the paths of others, they are all woven together in important ways, like a quilt, though the traces are difficult to trace.

It's as if those steps are sewing, sewing is the process of telling a story, and that story is your life. (192)

Empathy means stepping outside your own boundaries and traveling, expanding your scope.

This is truly an act of recognizing the real existence of another, and it is this very imaginative leap that gives birth to empathy. (286)

One of the charms of Andersen's The Snow Queen is that Gerda rescues Kai from the Snow Queen and their friendship is restored.

That's enough.

Many Native American stories never seem to end.

Those who entered the animal world did not return, but continued to exert some power as ancestors, founders, or benefactors.

The process by which Siddhartha, who was rich, well-off, loved, protected, and privileged, shakes off all of that seems like the story unfolding in reverse.

He was born as if he were a model answer, but he left that safe harbor and went out into the sea of endless questions and tasks. (363)

Empathy for illness and suffering, and the labor of care and reflection, achieved through

A record of a beautiful personality

This book is, above all, a story about a mother and a daughter.

It is a narrative about how a daughter loves, hates, overcomes, and understands her mother.

It is a narrative that shows how a daughter grows up and eventually achieves meaningful existential achievements.

To exaggerate a bit, it could be said to be a model of feminist growth narrative.

It can be said to be an alternative coming-of-age narrative that is fundamentally different from the typical modern masculine coming-of-age narrative of being overwhelmed by the father, competing with the father, killing the father, and taking over the mother.

Caring for other people (or animals), reading, listening to, and writing about other stories, are all closely linked tasks in this book.

It is a labor that requires the ability to empathize, which is based on imagination, and it is a labor that requires honest sweat.

Solnit's 'self' formed through this labor may not fit in with "conventional things like palaces, wealth, and revenge," but it may be richer and more special than those things.

As much as Mary Wollstonecraft achieved in writing Frankenstein.

There is a divine, artistic, parental power there that truly creates something.

At that time, my mother's condition felt like a fairy tale curse that could not be lifted by anything, something I could only accept.

But apricots were something that could be tried.

The fruit itself wasn't difficult to handle, but it felt like a metaphor, a reminder of some old heritage and mission.

But what was the metaphor for? (29-30)

My story is another variation of a story I've heard from many women over the years.

The story was about a mother who, like all mothers in the world, gave herself to everyone or someone else, and then tried to find herself again in her daughter. (36-37)

Mary, a young and poor woman in a time when women had little power, rises to an omnipotent position in her work.

He wrote a masterpiece that described the world in his own terms, depicted his vision of a world gone wrong, and dwarfed all other Romantic poets in its direct impact on the collective imagination.

Frankenstein is an exceptional work, a kind of archetype that always comes to mind when discussing imagination, like a legend or a fairy tale, and a symbol that encapsulates an aspect of the human condition. (79-80)

The three categories of parents, artists, and gods have something in common: they create something.

This novel raises the very important question of the responsibility a creator has for his creation.

It is also a question of the responsibility that humans have toward one another.

Frankenstein is, in fact, a conservative work, not in the sense that it defends conventional norms, but in the sense that it champions bonds of duty and affection over the pursuit of personal goals.

It also contained an invisible resentment toward the author's husband, the poet, who was stubborn, active, and often selfish. (81)

Illness also soothes loneliness in another way: by destroying the idea that we exist alone, self-sufficiently, and independently.

You need someone else's bone marrow or blood.

Care from professionals and loved ones is also needed.

You may be sick because you were bitten by a mosquito, contracted a virus, inherited a mutant gene, or a combination of these factors.

A person who is ill cannot ignore the fact that he or she is a biological being, finite, and interdependent with others. (191)

Strands just a few inches long are twisted together to form a single thread.

And just as words come together to form a story, the thread can become infinitely long.

The heroines in fairy tales create whatever they need to survive from spider webs, rags, nettles, and other things.

Scheherazade prevents her own death by continuing a thread of stories that never breaks.

She creates and creates again, adding new pieces, characters, and events to her own unbroken, unbreakable narrative thread.

On the contrary, Penelope, in order to avoid being married to the many suitors who flock to her, unravels the shroud she has woven for her father-in-law at night.

Through the process of spinning thread, weaving cloth, and then unraveling it again, these women conquered time itself.

Although the word "conqueror" itself is a masculine noun, this conquest was feminine. (194)

Before the word 'spinster' came to have a pejorative meaning of 'old maid,' when the spinning wheel symbolized the feminine domain in the home, every woman was a spinster, a person who spun yarn. (194)

A thoughtful person does not completely forget old age, illness, and death.

But most of us, either intentionally or for other reasons, forget about it to some extent.

We know it, but we don't experience or imagine it vividly enough to influence our decisions.

But once you realize it, whether it's you or us, everything changes.

I think I learned a little about it during the apricot harvest that year, when my elderly mother was ill, and I was soon hospitalized, my friend Ann was dying, and Nellie's daughter was born in critical condition. (222)

Of course, there was a sharp edge to my mother's joke that I seemed like her mother.

On the other hand, my mother was always confused about how this world came to be and what kind of relationship we had.

Time flows backwards for Alzheimer's patients, so I might have been my mother's mother.

I really had to take on the role of mother sometimes. (329)

A trip to Iceland, a journey away from myself and into the center of the world.

From a slightly different perspective, this book is also a travel essay about a writer from the American West who traveled to Iceland.

Thanks to the author's exceptional sense of place and space, this book has a special sense of depth and space.

Solnit is a good traveler, possessing both the ability to fully savor the familiar places of the American West and the ability to imagine other stories and other selves in faraway places.

The author effectively convinces us through his travels that just as it is important to delve deep into the self, it is equally important to break out of oneself, that it is necessary to love one's hometown while also seeking to reach out into the larger world, and that the ability to go in both directions is crucial.

Sometimes, going outside can help you get to the heart of the problem you've been holding onto.

The observations and descriptions of Iceland's exotic landscapes are enhanced by the many beautiful and sad stories told there.

In Iceland, Solnit contemplates darkness and light, cold and warmth, with a unique perspective.

And that kind of thinking naturally leads to the story of polar bears eating their own kind.

The sorrow continues over human arrogance and ignorance that is making the place we live in uninhabitable.

Her diverse facets as an essayist, historian, art critic, environmental activist, and someone's daughter, sister, and friend shine through.

I discovered books and places before I found friends or teachers, and while it may not be the same as what people give, they have given me a lot.

As a child, I used to vent whenever I had a problem.

In a world where inside and outside are turned upside down, anywhere but home is safe.

Fortunately, there were oak trees, hills, a stream, a small forest, birds, an old pasture and stable, and a jutting rock.

Such open spaces encouraged me to emerge from the personal and embrace a world devoid of humans. (54)

If we had said, “I don’t want to go,” back then, we would have wondered forever what would have happened.

We would have to live with the feeling that we had rejected a treasure that could have been ours, that we had rejected an opportunity to live life to the fullest.

The important thing is that we said “yes” to adventure, to the unknown, to possibility. (59)

It was as if the book had become a door.

People come into my life through books and lead me into theirs.

It was as if an unexpected sign had been created.

For the seven months leading up to my first actual visit, Iceland was a talisman, a window to another world.

It occurred to me that there was a place far away from all the troubles that had befallen me, and that I too would soon be able to escape from them. (115)

Hermaphroditic polar bears began appearing about 20 years ago.

It was a mutant that was unable to reproduce.

Because of these changes, polar bears are endangered.

It was the result of pollutants that had been carried in by currents or by migratory birds accumulating in the body.

Then there was the incident where a bear drowned.

The victims were bears who could not leave the area even though the ice that had been their habitat had melted and disappeared.

In Mary Shelley's novels, the abnormal nature was the exception, and the rest of the world was mostly wild or orderly.

She never imagined that we could all become Frankensteins.

A situation where the surrounding landscape has become a monster, chasing and being chased, where pollutants are spreading everywhere from inside our bodies to the ends of the earth. (230)

In the darkness, many things blend together.

In this way, passion becomes love, and as a result of the act of sharing love, all nature and form come into being.

Mixing is dangerous.

At least in terms of the boundaries that define the self, that is the case.

Darkness gives birth to something, and what is born that way, whether it be life or art, demands a loving attention to the unknown.

It means entering into a realm where you yourself don't know exactly what will happen next.

Creation always takes place in the dark.

Creating something only happens when you don't know exactly what you're doing.

When light shines, the specific shape or shadow of the thought is revealed and recognized by others, but it is not in the light that it is created. (272)

I felt at home there, more at home than anywhere else in Iceland.

The title of Jules Verne's novel about Iceland was Journey to the Center of the Earth, and it seemed that the experience inside the labyrinth was the 'journey' or the 'center' of it all. (276)

Recommendation

I believe in the power of a larger story to cleanse the toxins of bad stories and ultimately flow into a river of beautiful stories.

Solnit is a story warrior who fights and ultimately wins against the spell of bad stories imposed on her by creating more powerful stories.

Jeong Yeo-ul

This is the most specific 'proverb' I've ever read.

There is not a single phrase floating in the air.

Only working women can write such things.

Intelligence and insight are powers that only the weak can possess.

It's true that reading eases the pain of life.

It soothes loneliness and the desire to die.

I believe that we can connect just by reading.

Jeong Hee-jin

It's an amazing book that transcends genres.

As with previous books, the power of this one comes from the placement of the narrative's subtle neurons.

San Francisco Chronicle

Solnit, a master of lyrical prose, writes about her life, her family, and her reading.

In the process, he reconsiders the myths and thoughts that created his own world.

New Yorker

Reading this book feels like a dream.

It is the result of the tireless labor of a great mind.

Readers can weave a tremendous number of threads into a single story, and this allows us to see how well our stories are interconnected.

North Forum

A profound and moving explanation of why we create, why we tell stories.

I have never seen a more beautiful and compelling piece of literary nonfiction.

American Scholar

Solnit argues that we can continually change who we are and what we want.

Even in the most difficult and fateful times, it is the same.

Oprah.com

Solnit calls us to become bolder and more creative thinkers.

He intuitively discerns connections between seemingly unconnected topics and encourages readers to follow their own path.

Daily Beast

It's a masterpiece.

Solnit is one of the few writers who can guide us through the never-ending work of creating the self.

Nick Flynn

When you sit down with a Solnit book, something changes.

The world becomes a little clearer and at the same time a little more mysterious.

Here is the truest voice we know.

Each book Solnit publishes becomes a new map of the world.

Mark Doty

The power of stories that connect you and me and help us overcome life's challenges.

“I believe in the power of a larger story to cleanse the poison of a bad story and ultimately flow into a river of beautiful stories.

“Solnit is a warrior of storytelling who fights and ultimately wins against the spell of bad stories imposed on her by creating more powerful stories.” Jeong Yeo-ul (literary critic)

“This is the most specific proverb I have ever read.

There is not a single phrase floating in the air.

Only working women can write such things.

Intelligence and insight are powers that only the weak can possess.

It's true that reading eases the pain of life.

It also calms loneliness and the desire to die.

“I believe that we can connect just by reading.” Jeong Hee-jin (author of “Reading Like Jeong Hee-jin”)

A full-fledged essay that delves into the essence of Rebecca Solnit, author of "Mansplaining."

"Far and Near" is Rebecca Solnit's new book and a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Solnit gained fame in 2010 when she used the word "mansplaining" in a column to lucidly summarize the core of gender inequality that persists even in the 21st century.

This word was selected as the New York Times' '2010 Word of the Year', and Solnit was selected as one of the '25 Thinkers Who Will Change the World' by Utton Reader in the same year.

In 2015, the word "mansplaining" was added to the online version of the Oxford English Dictionary, and the column collection "Men Keep Trying to Teach Me Lessons" containing this article was introduced in Korea and selected as the book of the year by most media outlets.

In addition to this book, there are other books introduced in Korea that show the author's diverse interests and aspects, such as 『History of Walking』, 『Gaze at These Ruins』, and 『Hope in the Darkness』. In particular, 『Far and Near』 is significant in that it is a full-fledged work that most comprehensively shows such diverse aspects.

The book's main themes are reading and writing, solitude and solidarity, illness and care, life and death, mothers and daughters, Iceland and the Arctic.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, C.

Solnit uses a variety of stories, including S. Lewis's 'The Chronicles of Narnia', Freucen's 'The Polar Adventure', Che Guevara's 'The Motorcycle Diaries', and oral fairy tales such as 'The Swan Prince', 'Lumpenstiltskin', and 'The Snow Queen', to observe, think about, and ultimately understand the lives around her.

It is a different kind of understanding than making excuses for someone, covering up someone's mistakes, or showing off the writer's superiority.

The author calls this forgiveness and love.

With this warm and objective perspective, the author meticulously observes the role stories play in shaping our lives and relationships.

It is a unique essay, a memoir of intimacy, yet also eloquently about the public effects of reading and writing, a work that only Solnit could write.

What's your story? The power of stories that make us who we are.

The overarching theme that ties together the diverse topics of this book is the power of storytelling.

We weave stories to form our identity.

As Solnit says, the self is an important work of art that our lives create, and it is the work that turns everyone into an artist.

For example, many fairy tales deal with problem solving, and the protagonists of fairy tales become 'themselves' in the process of solving the problem.

This is a basic principle of storytelling.

A story is a process of discovering who we are, and in the process, with the help of others, we become aware of our limitations, overcome them, and become someone else.

Our stories are only possible by constantly encountering other people's stories along the way.

This also means that the ability to ‘listen’ and ‘read’, as well as the ability to empathize with and understand others, are fundamentally necessary in creating a ‘self’.

The book calls up countless stories, including classics like Frankenstein and archetypal narratives like The Swan Prince, as well as the story of an Eskimo woman who survived the extreme cold by eating the corpses of her husband and child, the story of a firefighter who saved a girl who fell into a well in front of the world on TV and then committed suicide as a result, the story of a polar bear that eats a polar bear that looks just like itself, and above all, the story of Solnit's mother, which could be called a darker version of Cinderella.

Understanding how these stories transformed Solnit can, in turn, influence our own lives.

This book, Solnit's story, transcends physical distance and firmly connects her life with ours.

In fairy tales, power itself is rarely a suitable means of survival.

Rather, it is often the powerless who unite and achieve success, often through acts of kindness toward one another.

Those who repay this deed are the ones who leave the beehive unbroken, the birds released without killing them, and the old women who welcome us with respect.

Kindness sown like a seed to a weak being bears fruit in a fairy tale, and sometimes even in reality, in moments of crisis. (28)

Like many who become writers, I too have been lost in books since childhood.

He disappeared into it as if he was running into the forest.

What surprised me, and still surprises me, is that beyond the forest of stories and solitude, there is a place, and if you go out there, you can meet people.

Writers are, and need to be, isolated by the nature of their profession.

Sometimes I think talent isn't the issue.

A writer's talent is not as rare as people think.

Rather, that talent is partly revealed in the ability to endure long periods of solitude and continue working.

Before being a writer, a writer is a reader, and he lives in and across books.

To live in another's life, and also in another's head, in that act which is deeply intimate, yet also utterly lonely. (96)

What we call a book is not a real book, but the potential it holds, like a musical score or a seed.

A book exists only when it is read, and its true home is in the reader's head, where the orchestra resonates and the seeds germinate.

A book is a heart that beats only in another person's body. (100)

Writing is an act of saying to no one what one cannot say to anyone, while at the same time saying to everyone what one cannot say to anyone.

Or, it is an act of telling a story that cannot be told to anyone now, to someone who may become a reader in the future.

You discover that you can write down and share with strangers stories so sensitive, so personal, so nebulous that you would normally never imagine telling even the closest of people, words that would otherwise escape the ears of others.

Writing speaks to a complete stranger in silence, and the story finds its voice and resonates through solitary reading.

Isn't that the loneliness shared through writing?

Footprints were clearly imprinted on the hard, damp sand at low tide.

It would remain like that until the tide came in again and completely erased the traces of its passage.

I love looking at the long line we each leave behind.

Sometimes I imagine my life that way.

As if each step were a stitch in a needle, as if I were a needle and the world was being sewn along the path I took with each step I took.

Although they intersect with the paths of others, they are all woven together in important ways, like a quilt, though the traces are difficult to trace.

It's as if those steps are sewing, sewing is the process of telling a story, and that story is your life. (192)

Empathy means stepping outside your own boundaries and traveling, expanding your scope.

This is truly an act of recognizing the real existence of another, and it is this very imaginative leap that gives birth to empathy. (286)

One of the charms of Andersen's The Snow Queen is that Gerda rescues Kai from the Snow Queen and their friendship is restored.

That's enough.

Many Native American stories never seem to end.

Those who entered the animal world did not return, but continued to exert some power as ancestors, founders, or benefactors.

The process by which Siddhartha, who was rich, well-off, loved, protected, and privileged, shakes off all of that seems like the story unfolding in reverse.

He was born as if he were a model answer, but he left that safe harbor and went out into the sea of endless questions and tasks. (363)

Empathy for illness and suffering, and the labor of care and reflection, achieved through

A record of a beautiful personality

This book is, above all, a story about a mother and a daughter.

It is a narrative about how a daughter loves, hates, overcomes, and understands her mother.

It is a narrative that shows how a daughter grows up and eventually achieves meaningful existential achievements.

To exaggerate a bit, it could be said to be a model of feminist growth narrative.

It can be said to be an alternative coming-of-age narrative that is fundamentally different from the typical modern masculine coming-of-age narrative of being overwhelmed by the father, competing with the father, killing the father, and taking over the mother.

Caring for other people (or animals), reading, listening to, and writing about other stories, are all closely linked tasks in this book.

It is a labor that requires the ability to empathize, which is based on imagination, and it is a labor that requires honest sweat.

Solnit's 'self' formed through this labor may not fit in with "conventional things like palaces, wealth, and revenge," but it may be richer and more special than those things.

As much as Mary Wollstonecraft achieved in writing Frankenstein.

There is a divine, artistic, parental power there that truly creates something.

At that time, my mother's condition felt like a fairy tale curse that could not be lifted by anything, something I could only accept.

But apricots were something that could be tried.

The fruit itself wasn't difficult to handle, but it felt like a metaphor, a reminder of some old heritage and mission.

But what was the metaphor for? (29-30)

My story is another variation of a story I've heard from many women over the years.

The story was about a mother who, like all mothers in the world, gave herself to everyone or someone else, and then tried to find herself again in her daughter. (36-37)

Mary, a young and poor woman in a time when women had little power, rises to an omnipotent position in her work.

He wrote a masterpiece that described the world in his own terms, depicted his vision of a world gone wrong, and dwarfed all other Romantic poets in its direct impact on the collective imagination.

Frankenstein is an exceptional work, a kind of archetype that always comes to mind when discussing imagination, like a legend or a fairy tale, and a symbol that encapsulates an aspect of the human condition. (79-80)

The three categories of parents, artists, and gods have something in common: they create something.

This novel raises the very important question of the responsibility a creator has for his creation.

It is also a question of the responsibility that humans have toward one another.

Frankenstein is, in fact, a conservative work, not in the sense that it defends conventional norms, but in the sense that it champions bonds of duty and affection over the pursuit of personal goals.

It also contained an invisible resentment toward the author's husband, the poet, who was stubborn, active, and often selfish. (81)

Illness also soothes loneliness in another way: by destroying the idea that we exist alone, self-sufficiently, and independently.

You need someone else's bone marrow or blood.

Care from professionals and loved ones is also needed.

You may be sick because you were bitten by a mosquito, contracted a virus, inherited a mutant gene, or a combination of these factors.

A person who is ill cannot ignore the fact that he or she is a biological being, finite, and interdependent with others. (191)

Strands just a few inches long are twisted together to form a single thread.

And just as words come together to form a story, the thread can become infinitely long.

The heroines in fairy tales create whatever they need to survive from spider webs, rags, nettles, and other things.

Scheherazade prevents her own death by continuing a thread of stories that never breaks.

She creates and creates again, adding new pieces, characters, and events to her own unbroken, unbreakable narrative thread.

On the contrary, Penelope, in order to avoid being married to the many suitors who flock to her, unravels the shroud she has woven for her father-in-law at night.

Through the process of spinning thread, weaving cloth, and then unraveling it again, these women conquered time itself.

Although the word "conqueror" itself is a masculine noun, this conquest was feminine. (194)

Before the word 'spinster' came to have a pejorative meaning of 'old maid,' when the spinning wheel symbolized the feminine domain in the home, every woman was a spinster, a person who spun yarn. (194)

A thoughtful person does not completely forget old age, illness, and death.

But most of us, either intentionally or for other reasons, forget about it to some extent.

We know it, but we don't experience or imagine it vividly enough to influence our decisions.

But once you realize it, whether it's you or us, everything changes.

I think I learned a little about it during the apricot harvest that year, when my elderly mother was ill, and I was soon hospitalized, my friend Ann was dying, and Nellie's daughter was born in critical condition. (222)

Of course, there was a sharp edge to my mother's joke that I seemed like her mother.

On the other hand, my mother was always confused about how this world came to be and what kind of relationship we had.

Time flows backwards for Alzheimer's patients, so I might have been my mother's mother.

I really had to take on the role of mother sometimes. (329)

A trip to Iceland, a journey away from myself and into the center of the world.

From a slightly different perspective, this book is also a travel essay about a writer from the American West who traveled to Iceland.

Thanks to the author's exceptional sense of place and space, this book has a special sense of depth and space.

Solnit is a good traveler, possessing both the ability to fully savor the familiar places of the American West and the ability to imagine other stories and other selves in faraway places.

The author effectively convinces us through his travels that just as it is important to delve deep into the self, it is equally important to break out of oneself, that it is necessary to love one's hometown while also seeking to reach out into the larger world, and that the ability to go in both directions is crucial.

Sometimes, going outside can help you get to the heart of the problem you've been holding onto.

The observations and descriptions of Iceland's exotic landscapes are enhanced by the many beautiful and sad stories told there.

In Iceland, Solnit contemplates darkness and light, cold and warmth, with a unique perspective.

And that kind of thinking naturally leads to the story of polar bears eating their own kind.

The sorrow continues over human arrogance and ignorance that is making the place we live in uninhabitable.

Her diverse facets as an essayist, historian, art critic, environmental activist, and someone's daughter, sister, and friend shine through.

I discovered books and places before I found friends or teachers, and while it may not be the same as what people give, they have given me a lot.

As a child, I used to vent whenever I had a problem.

In a world where inside and outside are turned upside down, anywhere but home is safe.

Fortunately, there were oak trees, hills, a stream, a small forest, birds, an old pasture and stable, and a jutting rock.

Such open spaces encouraged me to emerge from the personal and embrace a world devoid of humans. (54)

If we had said, “I don’t want to go,” back then, we would have wondered forever what would have happened.

We would have to live with the feeling that we had rejected a treasure that could have been ours, that we had rejected an opportunity to live life to the fullest.

The important thing is that we said “yes” to adventure, to the unknown, to possibility. (59)

It was as if the book had become a door.

People come into my life through books and lead me into theirs.

It was as if an unexpected sign had been created.

For the seven months leading up to my first actual visit, Iceland was a talisman, a window to another world.

It occurred to me that there was a place far away from all the troubles that had befallen me, and that I too would soon be able to escape from them. (115)

Hermaphroditic polar bears began appearing about 20 years ago.

It was a mutant that was unable to reproduce.

Because of these changes, polar bears are endangered.

It was the result of pollutants that had been carried in by currents or by migratory birds accumulating in the body.

Then there was the incident where a bear drowned.

The victims were bears who could not leave the area even though the ice that had been their habitat had melted and disappeared.

In Mary Shelley's novels, the abnormal nature was the exception, and the rest of the world was mostly wild or orderly.

She never imagined that we could all become Frankensteins.

A situation where the surrounding landscape has become a monster, chasing and being chased, where pollutants are spreading everywhere from inside our bodies to the ends of the earth. (230)

In the darkness, many things blend together.

In this way, passion becomes love, and as a result of the act of sharing love, all nature and form come into being.

Mixing is dangerous.

At least in terms of the boundaries that define the self, that is the case.

Darkness gives birth to something, and what is born that way, whether it be life or art, demands a loving attention to the unknown.

It means entering into a realm where you yourself don't know exactly what will happen next.

Creation always takes place in the dark.

Creating something only happens when you don't know exactly what you're doing.

When light shines, the specific shape or shadow of the thought is revealed and recognized by others, but it is not in the light that it is created. (272)

I felt at home there, more at home than anywhere else in Iceland.

The title of Jules Verne's novel about Iceland was Journey to the Center of the Earth, and it seemed that the experience inside the labyrinth was the 'journey' or the 'center' of it all. (276)

Recommendation

I believe in the power of a larger story to cleanse the toxins of bad stories and ultimately flow into a river of beautiful stories.

Solnit is a story warrior who fights and ultimately wins against the spell of bad stories imposed on her by creating more powerful stories.

Jeong Yeo-ul

This is the most specific 'proverb' I've ever read.

There is not a single phrase floating in the air.

Only working women can write such things.

Intelligence and insight are powers that only the weak can possess.

It's true that reading eases the pain of life.

It soothes loneliness and the desire to die.

I believe that we can connect just by reading.

Jeong Hee-jin

It's an amazing book that transcends genres.

As with previous books, the power of this one comes from the placement of the narrative's subtle neurons.

San Francisco Chronicle

Solnit, a master of lyrical prose, writes about her life, her family, and her reading.

In the process, he reconsiders the myths and thoughts that created his own world.

New Yorker

Reading this book feels like a dream.

It is the result of the tireless labor of a great mind.

Readers can weave a tremendous number of threads into a single story, and this allows us to see how well our stories are interconnected.

North Forum

A profound and moving explanation of why we create, why we tell stories.

I have never seen a more beautiful and compelling piece of literary nonfiction.

American Scholar

Solnit argues that we can continually change who we are and what we want.

Even in the most difficult and fateful times, it is the same.

Oprah.com

Solnit calls us to become bolder and more creative thinkers.

He intuitively discerns connections between seemingly unconnected topics and encourages readers to follow their own path.

Daily Beast

It's a masterpiece.

Solnit is one of the few writers who can guide us through the never-ending work of creating the self.

Nick Flynn

When you sit down with a Solnit book, something changes.

The world becomes a little clearer and at the same time a little more mysterious.

Here is the truest voice we know.

Each book Solnit publishes becomes a new map of the world.

Mark Doty

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: February 11, 2016

- Page count, weight, size: 384 pages | 456g | 130*205*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788983717733

- ISBN10: 8983717734

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)