Proust and the Squid

|

Description

Book Introduction

Marion Wolff, a world-renowned cognitive neuroscientist and authority on reading, has republished her masterpiece, Proust and the Squid, using the original title. (The previous Korean edition was titled The Reading Brain.) In this book, Marion Wolff shocked readers by saying, "Humans were not born to read," and that reading is not an innate ability but an invented trait.

Encompassing literature, archaeology, linguistics, and neuroscience, this book is a contemporary classic on reading studies, answering questions such as when reading began, how reading became possible, why dyslexia occurs, and what reading can mean to humans in our rapidly shifting digital culture.

Encompassing literature, archaeology, linguistics, and neuroscience, this book is a contemporary classic on reading studies, answering questions such as when reading began, how reading became possible, why dyslexia occurs, and what reading can mean to humans in our rapidly shifting digital culture.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Korean edition

introduction

Part 1.

How did the brain learn to read?

Chapter 1.

Reading Lectures on Proust and the Squid

Chapter 2.

The brain that started reading letters

Chapter 3.

The Birth of the Alphabet and Socrates' Opposition

Part 2.

How the Brain Learns to Read

Chapter 4.

Reading development, to get started properly

Chapter 5.

A Look Inside the Brain of a Child Just Starting to Read

Chapter 6.

What skilled reading changes

Part 3.

When the brain can't learn to read

Chapter 7.

The Mystery of Dyslexia

Chapter 8.

The Relationship Between Dyslexia and Creativity

Chapter 9.

The Miracle of Reading and Beyond

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

introduction

Part 1.

How did the brain learn to read?

Chapter 1.

Reading Lectures on Proust and the Squid

Chapter 2.

The brain that started reading letters

Chapter 3.

The Birth of the Alphabet and Socrates' Opposition

Part 2.

How the Brain Learns to Read

Chapter 4.

Reading development, to get started properly

Chapter 5.

A Look Inside the Brain of a Child Just Starting to Read

Chapter 6.

What skilled reading changes

Part 3.

When the brain can't learn to read

Chapter 7.

The Mystery of Dyslexia

Chapter 8.

The Relationship Between Dyslexia and Creativity

Chapter 9.

The Miracle of Reading and Beyond

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Unlike genetically organized components like vision or language, reading has no direct genetic program that transmits the ability to offspring.

So, every time an individual's brain acquires the ability to read, the four layers above it must relearn from scratch how to form the necessary pathways.

This is what differentiates reading and all other cultural inventions from other processes.

That is why the ability to read does not appear naturally in children like visual or language abilities that are pre-programmed.

--- p.42

Among the legacy left by the Sumerians, there is one fact that is not well known but is worth knowing.

The point is that female royals learned to read.

Women had their own language called Emesal.

Emesal, meaning 'noble language', was used as the language of the common royal family and was distinguished from Emegir, meaning 'the language of princes'.

There were quite a few words in women's language that had different pronunciations.

In a place where men spoke the 'language of princes' and women spoke the 'language of nobility', students were expected to speak a different dialect in each hallway they entered.

So you can imagine how much cognitive complexity they required.

--- p.87

If we look at this overall history from a meta-perspective, we can see that the driving force that has promoted the development of intellectual thought in human history is not the first alphabet or the best alphabet, but writing itself.

As the 20th-century Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky explained, the act of transcribing spoken words and unspoken thoughts into text forces us to think, and in the process, the thoughts themselves change.

As humans have become more and more precise in their use of written language to communicate their thoughts, their capacity for abstract thought and the development of innovative ideas has also been fostered.

--- p.

132

Geschwind's conclusions about when a child's brain is sufficiently developed to read are supported by cross-lingual research.

It's worth noting the surprising cross-linguistic findings of a study conducted by British reading scholar Usha Goswami and her team.

In a study of three different languages, they found that European children who began reading at age five underperformed those who began reading at age seven.

The bottom line from this study is that teaching children to read before they are four or five years old is biologically reckless and may be counterproductive for many children.

--- p.

179

Todd Risley and Betty Hart conducted a study of a California community and found the chilling finding that some five-year-olds from language-poor environments heard 32 million fewer words than the average middle-class child.

The grim reality revealed in this study raises serious implications.

What Louisa Cook-Moats calls “verbal poverty” is not limited to the words children hear as they grow up.

Another study that looked at how many words three-year-olds could say found that children growing up in poverty used less than half the vocabulary of their more privileged peers.

--- p.191

The evolution of writing provided the cognitive foundation for the emergence of immensely important capacities that mark the first chapter of human intellectual history: documentation, systematization, classification, organization, internalization of language, awareness of self and others, and awareness of consciousness itself.

The direct factor that allowed all these abilities to be fully developed was not reading.

What has served as an unprecedented catalyst for the development of all these abilities is the secret gift of "thinking time," which lies at the core of the brain's design for reading.

--- p.376

The true tragedy of dyslexia is that the children who spend countless years publicly shamed for their inability to read are actually incredibly gifted, and no one tells them that the type of intelligence they possess is incredibly important to humanity.

No one tells those kids' friends that story.

This story is not intended to downplay or minimize the challenges that all dyslexic children face in their learning.

Quite the opposite.

The idea is to tell these children that they are all very important to us, and that it is our job to find ways to teach reading to their differently organized brains.

So, every time an individual's brain acquires the ability to read, the four layers above it must relearn from scratch how to form the necessary pathways.

This is what differentiates reading and all other cultural inventions from other processes.

That is why the ability to read does not appear naturally in children like visual or language abilities that are pre-programmed.

--- p.42

Among the legacy left by the Sumerians, there is one fact that is not well known but is worth knowing.

The point is that female royals learned to read.

Women had their own language called Emesal.

Emesal, meaning 'noble language', was used as the language of the common royal family and was distinguished from Emegir, meaning 'the language of princes'.

There were quite a few words in women's language that had different pronunciations.

In a place where men spoke the 'language of princes' and women spoke the 'language of nobility', students were expected to speak a different dialect in each hallway they entered.

So you can imagine how much cognitive complexity they required.

--- p.87

If we look at this overall history from a meta-perspective, we can see that the driving force that has promoted the development of intellectual thought in human history is not the first alphabet or the best alphabet, but writing itself.

As the 20th-century Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky explained, the act of transcribing spoken words and unspoken thoughts into text forces us to think, and in the process, the thoughts themselves change.

As humans have become more and more precise in their use of written language to communicate their thoughts, their capacity for abstract thought and the development of innovative ideas has also been fostered.

--- p.

132

Geschwind's conclusions about when a child's brain is sufficiently developed to read are supported by cross-lingual research.

It's worth noting the surprising cross-linguistic findings of a study conducted by British reading scholar Usha Goswami and her team.

In a study of three different languages, they found that European children who began reading at age five underperformed those who began reading at age seven.

The bottom line from this study is that teaching children to read before they are four or five years old is biologically reckless and may be counterproductive for many children.

--- p.

179

Todd Risley and Betty Hart conducted a study of a California community and found the chilling finding that some five-year-olds from language-poor environments heard 32 million fewer words than the average middle-class child.

The grim reality revealed in this study raises serious implications.

What Louisa Cook-Moats calls “verbal poverty” is not limited to the words children hear as they grow up.

Another study that looked at how many words three-year-olds could say found that children growing up in poverty used less than half the vocabulary of their more privileged peers.

--- p.191

The evolution of writing provided the cognitive foundation for the emergence of immensely important capacities that mark the first chapter of human intellectual history: documentation, systematization, classification, organization, internalization of language, awareness of self and others, and awareness of consciousness itself.

The direct factor that allowed all these abilities to be fully developed was not reading.

What has served as an unprecedented catalyst for the development of all these abilities is the secret gift of "thinking time," which lies at the core of the brain's design for reading.

--- p.376

The true tragedy of dyslexia is that the children who spend countless years publicly shamed for their inability to read are actually incredibly gifted, and no one tells them that the type of intelligence they possess is incredibly important to humanity.

No one tells those kids' friends that story.

This story is not intended to downplay or minimize the challenges that all dyslexic children face in their learning.

Quite the opposite.

The idea is to tell these children that they are all very important to us, and that it is our job to find ways to teach reading to their differently organized brains.

--- p.385

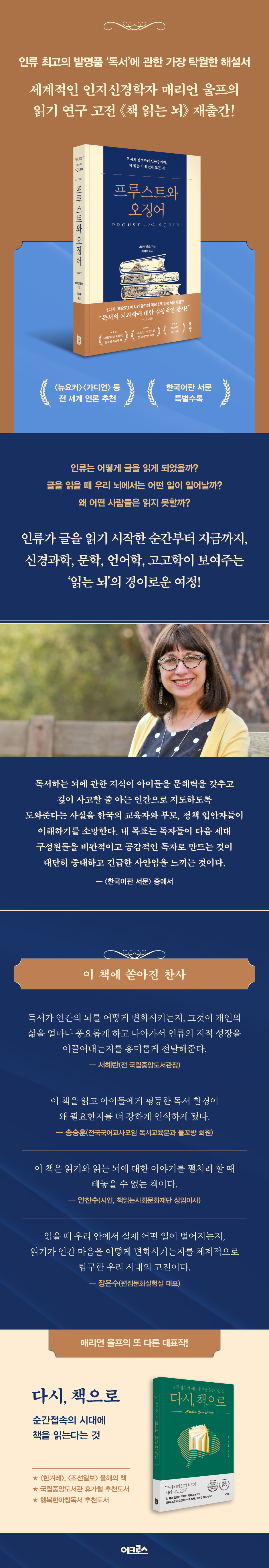

Publisher's Review

From the moment mankind began to read until now,

A wondrous journey of the "reading brain" revealed through literature, archaeology, linguistics, and neuroscience!

The classic reading research book, "The Reading Brain," by world-renowned cognitive neuroscientist Marion Wolff, has been republished!

- The brain science of reading, which has been highlighted by global media outlets such as The New Yorker and The Guardian.

- Publisher's Weekly's Best Nonfiction Books

- Includes preface to the Korean edition

Marion Woolf, a world-renowned cognitive neuroscientist and child development scholar, has republished her masterpiece, Proust and the Squid.

This book, which was published in Korea in 2009 under the title “The Brain that Reads Books,” was renamed “Proust and the Squid” to keep the original title.

A Korean preface has also been added to coincide with the republication.

Marion Wolf reminds us that Korea has the highest smartphone penetration rate in the world, and that we have lost the time to read in the midst of our rapid transition to a digital culture. She also emphasizes that we must not forget that the empathy for others, critical thinking and reasoning, and reflection that deep reading brings are the foundation of a good society.

"Proust and the Squid" is a masterpiece that has captivated not only those in the reading field but also the general public. It is a classic in the field of reading studies, translated and published in 13 countries, and has received praise from media outlets and experts around the world.

True to its title, which combines "Proust," which symbolizes the intellectual world of reading, and "squid," which symbolizes the neurological aspect of reading, "Proust and the Squid" discusses reading, humanity's greatest invention, in the most scientific and yet most literary way.

Drawing on diverse sources and vivid examples from neuroscience, literature, and archaeology, Marion Woolf illuminates what reading means to us as human beings.

"Proust and the Squid" also points out the reality of the rapid transition to digital culture.

As the tendency to acquire information through digital devices has increased significantly across all generations, including teenagers, concerns about digital addiction have grown louder.

There is also strong criticism that video-based learning that relies on digital devices can lead to a decline in concentration.

This rapid shift to digital culture is something that Marion Woolf warned about 15 years ago in Proust and the Squid.

This is why this book is still relevant today.

Humans were not born to read books.

: How did humans learn to read, and how does the brain learn to read?

“Reading is not an innate ability.” This is the first sentence of “Proust and the Squid.”

Marion Woolf's decisive declaration was a refreshing shock, overturning conventional views on reading.

We often think of reading as an innate ability, like speaking or falling asleep, but in fact, reading is closer to an acquired skill.

In the long history of modern humans spanning hundreds of thousands of years, reading began only a few thousand years ago.

Part 1 of "Proust and the Squid" traces the history of how humans first learned to read.

Through the development of the first human writing systems in the Sumerian and Egyptian civilizations and the formation of the alphabet in ancient Greece, we can gain insight into how humanity gradually approached a literacy-based society.

Although we cannot directly observe how the Sumerians and Egyptians acquired the ability to read, we can indirectly guess how by observing how reading ability developed within an individual.

Marion Wolfe explains that the reason humans acquired the ability to read is because of the brain's plasticity.

Brain plasticity refers to the brain's ability to change its neural circuits on its own.

In this book, Marion Wolf details the process by which the brain forms a kind of reading circuit through external sensory stimulation.

When reading, not just one part of the human brain is stimulated, but all parts connected to the reading circuit are stimulated as a whole.

As a result of these stimuli, reading circuits are formed and changed, making reading possible.

However, Marion Wolf says that this reading circuit expands or contracts depending on whether or not you continue reading.

Even people who were good at reading books can lose their reading skills and fall to a beginner's level if they stop reading, and even people who were not good at reading can improve their literacy skills if they make a consistent effort to read.

This is why reading ability varies from person to person and from time to time.

People who can't read

: What causes dyslexia and how should we view dyslexia?

Another important topic that Marion Wolf addresses in this book is dyslexia.

If the process described above allowed humans to learn to read, how should we view those who are unable to read? If reading is not an innate ability, isn't dyslexia perhaps a natural symptom? Why is dyslexia so frequently found in creative geniuses like Thomas Edison and Leonardo da Vinci? As a world-renowned reading researcher and the mother of a son with dyslexia, Marion Wolf offers a fresh and accurate perspective on dyslexia.

Dyslexia is a condition in which reading circuitry is not normally wired, leading to problems with reading.

The unique reading circuitry of dyslexics sometimes results in extreme creativity.

Representative examples include figures who have left their mark on history through creative thinking, such as Da Vinci, Einstein, Edison, and Gaudi.

In an illiterate society, these people would be at no disadvantage.

But in a society based on the ability to read and write, it suffers.

What's more problematic is the way we look at them.

Dyslexia does not mean that everyone with dyslexia has a low IQ, nor does it mean that everyone with dyslexia has amazing genius.

However, if parents or teachers fail to provide the necessary treatment or support due to these prejudices, the opportunity for them to develop their unique potential will be lost forever.

Marion Wolf likens studying dyslexia to "studying baby squid that can't swim fast."

Research on dyslexia says it can help us understand what the squid needs to swim well and its unique talents that allow it to live happily without having to swim like other squid.

And he emphasizes that the true meaning of dyslexia research is to ensure that no child's potential is wasted.

Socrates' Concerns and the Future

: Why should we read?

When the alphabet first began to be developed, there was one man in ancient Greece who strongly opposed reading.

It's Socrates.

Socrates opposed young people acquiring knowledge through reading.

This is because I believe that reading allows for information to be acquired in an overly superficial manner and hinders the process of moving toward true understanding.

Does this argument sound familiar? Socrates's argument echoes our own concerns about children's access to information through digital media.

In the final chapter, Chapter 9, Wolfe envisions the emergence of a "digital brain" in an era where digital media becomes the primary means of sharing information.

This also anticipated the sequel, “Back to the Book,” which would be published ten years after “Proust and the Squid.”

The success of reading depends not on deciphering the text, but on taking the time to think and reading deeply.

As we become accustomed to instant access through digital devices and short-form content becomes popular, Marion Wolf's concerns have become reality.

Now is the time to ask not how to read, but why we should read.

As Proust wrote a century ago, reading allows us “to discover our own wisdom beyond the wisdom of the author.”

In “On Reading,” Proust viewed reading as a kind of “sanctuary” of the intellect.

Because I saw it as a place where readers could access thousands of realities and truths they would never encounter or understand anywhere else, a place where each new reality and truth could transform their own lives without leaving the comfort of their armchair.

(Page 33) Proust is right.

Reading is not simply deciphering letters.

It is a wondrous process of visually perceiving letters, the brain processing that information, linking it to our memories, and using the accumulated knowledge as a foundation for insight and reflection, before it is transformed into wisdom for life.

This process is the 'deep reading' that Marion Woolf consistently emphasizes.

In a digital age accustomed to instantaneous and fleeting stimuli, Marion Wolf proves through Proust and the Squid why humanity still needs to read.

A wondrous journey of the "reading brain" revealed through literature, archaeology, linguistics, and neuroscience!

The classic reading research book, "The Reading Brain," by world-renowned cognitive neuroscientist Marion Wolff, has been republished!

- The brain science of reading, which has been highlighted by global media outlets such as The New Yorker and The Guardian.

- Publisher's Weekly's Best Nonfiction Books

- Includes preface to the Korean edition

Marion Woolf, a world-renowned cognitive neuroscientist and child development scholar, has republished her masterpiece, Proust and the Squid.

This book, which was published in Korea in 2009 under the title “The Brain that Reads Books,” was renamed “Proust and the Squid” to keep the original title.

A Korean preface has also been added to coincide with the republication.

Marion Wolf reminds us that Korea has the highest smartphone penetration rate in the world, and that we have lost the time to read in the midst of our rapid transition to a digital culture. She also emphasizes that we must not forget that the empathy for others, critical thinking and reasoning, and reflection that deep reading brings are the foundation of a good society.

"Proust and the Squid" is a masterpiece that has captivated not only those in the reading field but also the general public. It is a classic in the field of reading studies, translated and published in 13 countries, and has received praise from media outlets and experts around the world.

True to its title, which combines "Proust," which symbolizes the intellectual world of reading, and "squid," which symbolizes the neurological aspect of reading, "Proust and the Squid" discusses reading, humanity's greatest invention, in the most scientific and yet most literary way.

Drawing on diverse sources and vivid examples from neuroscience, literature, and archaeology, Marion Woolf illuminates what reading means to us as human beings.

"Proust and the Squid" also points out the reality of the rapid transition to digital culture.

As the tendency to acquire information through digital devices has increased significantly across all generations, including teenagers, concerns about digital addiction have grown louder.

There is also strong criticism that video-based learning that relies on digital devices can lead to a decline in concentration.

This rapid shift to digital culture is something that Marion Woolf warned about 15 years ago in Proust and the Squid.

This is why this book is still relevant today.

Humans were not born to read books.

: How did humans learn to read, and how does the brain learn to read?

“Reading is not an innate ability.” This is the first sentence of “Proust and the Squid.”

Marion Woolf's decisive declaration was a refreshing shock, overturning conventional views on reading.

We often think of reading as an innate ability, like speaking or falling asleep, but in fact, reading is closer to an acquired skill.

In the long history of modern humans spanning hundreds of thousands of years, reading began only a few thousand years ago.

Part 1 of "Proust and the Squid" traces the history of how humans first learned to read.

Through the development of the first human writing systems in the Sumerian and Egyptian civilizations and the formation of the alphabet in ancient Greece, we can gain insight into how humanity gradually approached a literacy-based society.

Although we cannot directly observe how the Sumerians and Egyptians acquired the ability to read, we can indirectly guess how by observing how reading ability developed within an individual.

Marion Wolfe explains that the reason humans acquired the ability to read is because of the brain's plasticity.

Brain plasticity refers to the brain's ability to change its neural circuits on its own.

In this book, Marion Wolf details the process by which the brain forms a kind of reading circuit through external sensory stimulation.

When reading, not just one part of the human brain is stimulated, but all parts connected to the reading circuit are stimulated as a whole.

As a result of these stimuli, reading circuits are formed and changed, making reading possible.

However, Marion Wolf says that this reading circuit expands or contracts depending on whether or not you continue reading.

Even people who were good at reading books can lose their reading skills and fall to a beginner's level if they stop reading, and even people who were not good at reading can improve their literacy skills if they make a consistent effort to read.

This is why reading ability varies from person to person and from time to time.

People who can't read

: What causes dyslexia and how should we view dyslexia?

Another important topic that Marion Wolf addresses in this book is dyslexia.

If the process described above allowed humans to learn to read, how should we view those who are unable to read? If reading is not an innate ability, isn't dyslexia perhaps a natural symptom? Why is dyslexia so frequently found in creative geniuses like Thomas Edison and Leonardo da Vinci? As a world-renowned reading researcher and the mother of a son with dyslexia, Marion Wolf offers a fresh and accurate perspective on dyslexia.

Dyslexia is a condition in which reading circuitry is not normally wired, leading to problems with reading.

The unique reading circuitry of dyslexics sometimes results in extreme creativity.

Representative examples include figures who have left their mark on history through creative thinking, such as Da Vinci, Einstein, Edison, and Gaudi.

In an illiterate society, these people would be at no disadvantage.

But in a society based on the ability to read and write, it suffers.

What's more problematic is the way we look at them.

Dyslexia does not mean that everyone with dyslexia has a low IQ, nor does it mean that everyone with dyslexia has amazing genius.

However, if parents or teachers fail to provide the necessary treatment or support due to these prejudices, the opportunity for them to develop their unique potential will be lost forever.

Marion Wolf likens studying dyslexia to "studying baby squid that can't swim fast."

Research on dyslexia says it can help us understand what the squid needs to swim well and its unique talents that allow it to live happily without having to swim like other squid.

And he emphasizes that the true meaning of dyslexia research is to ensure that no child's potential is wasted.

Socrates' Concerns and the Future

: Why should we read?

When the alphabet first began to be developed, there was one man in ancient Greece who strongly opposed reading.

It's Socrates.

Socrates opposed young people acquiring knowledge through reading.

This is because I believe that reading allows for information to be acquired in an overly superficial manner and hinders the process of moving toward true understanding.

Does this argument sound familiar? Socrates's argument echoes our own concerns about children's access to information through digital media.

In the final chapter, Chapter 9, Wolfe envisions the emergence of a "digital brain" in an era where digital media becomes the primary means of sharing information.

This also anticipated the sequel, “Back to the Book,” which would be published ten years after “Proust and the Squid.”

The success of reading depends not on deciphering the text, but on taking the time to think and reading deeply.

As we become accustomed to instant access through digital devices and short-form content becomes popular, Marion Wolf's concerns have become reality.

Now is the time to ask not how to read, but why we should read.

As Proust wrote a century ago, reading allows us “to discover our own wisdom beyond the wisdom of the author.”

In “On Reading,” Proust viewed reading as a kind of “sanctuary” of the intellect.

Because I saw it as a place where readers could access thousands of realities and truths they would never encounter or understand anywhere else, a place where each new reality and truth could transform their own lives without leaving the comfort of their armchair.

(Page 33) Proust is right.

Reading is not simply deciphering letters.

It is a wondrous process of visually perceiving letters, the brain processing that information, linking it to our memories, and using the accumulated knowledge as a foundation for insight and reflection, before it is transformed into wisdom for life.

This process is the 'deep reading' that Marion Woolf consistently emphasizes.

In a digital age accustomed to instantaneous and fleeting stimuli, Marion Wolf proves through Proust and the Squid why humanity still needs to read.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 20, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 456 pages | 620g | 147*215*25mm

- ISBN13: 9791167741547

- ISBN10: 1167741544

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)