The Language of the Goddess

|

Description

Book Introduction

The book 『The Language of the Goddess』, which received numerous requests for republication from readers, has been republished.

This monumental book showcases the goddess traditions of 'Old Europe' (Europe before the formation of Indo-European civilization) through artifacts from around 7000 BC to 3500 BC, and explains the traces of various goddess traditions and matriarchal societies that have continued since then.

About 2,000 relics and icons are introduced, categorized into symbolic groups according to their respective meanings.

Within the four major branches of 'Bonding of Life', 'Rebirth and the Eternal World', 'Death and Rebirth', and 'Energy and Flow', the symbols are explained in 28 smaller branches, ranging from V-shaped patterns and wave patterns to shapes of birds, snakes, sheep, and bears.

The appendix at the back of the book includes a glossary of symbolic terms, types of goddesses and gods and their roles, a chronology, and a map of artifact excavation sites, vividly and meticulously recreating the world 10,000 years ago.

This monumental book showcases the goddess traditions of 'Old Europe' (Europe before the formation of Indo-European civilization) through artifacts from around 7000 BC to 3500 BC, and explains the traces of various goddess traditions and matriarchal societies that have continued since then.

About 2,000 relics and icons are introduced, categorized into symbolic groups according to their respective meanings.

Within the four major branches of 'Bonding of Life', 'Rebirth and the Eternal World', 'Death and Rebirth', and 'Energy and Flow', the symbols are explained in 28 smaller branches, ranging from V-shaped patterns and wave patterns to shapes of birds, snakes, sheep, and bears.

The appendix at the back of the book includes a glossary of symbolic terms, types of goddesses and gods and their roles, a chronology, and a map of artifact excavation sites, vividly and meticulously recreating the world 10,000 years ago.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation - Joseph Campbell

Author's Preface

Recommendation for the Korean edition - Kim Jong-il (Professor, Department of Archaeology and Art History, Seoul National University)

Translator's Preface

Category of symbols

Part I: The Gift of Life

Chapter 1: Symbols of the New Goddess: The V-Shaped Pattern and the Wedge Pattern

Chapter 2 Zigzag Pattern and M Pattern

Chapter 3: Meander Patterns and Waterfowl

Chapter 4: The Breasts of the New Goddess

Chapter 5 Wave Pattern

Chapter 6: The Eyes of the Goddess

Chapter 7 Open Mouth/Goddess's Beak

Chapter 8: Grantors of Craft Skills Related to Spinning, Weaving, Metallurgy, and Musical Instruments

Chapter 9: The Ram, the Animal of the New Goddess

Chapter 10: Mesh Pattern

Chapter 11: The Power of the Three Lines and the Number 3

Chapter 12: The Vulva and Birth

Chapter 13: Deer and Bear as Mothers

Chapter 14 The Snake

Part II: Regeneration and the Eternal World

Chapter 15: The Great Mother

Chapter 16: The Power of Two

Chapter 17: The Gods and the Daimons

Part III: Death and Rebirth

Chapter 18: Symbols of Death

Chapter 19 Al

Chapter 20: The Pillars of Life

Chapter 21: Symbols of Regeneration: The Vulva: The Triangle, the Hourglass, and the Bird's Claw

Chapter 22: The Ship of Rebirth

Chapter 23: The Frog, the Hedgehog, and the Fish

Chapter 24: Hydrogen, Bees, and Butterflies

Part IV Energy and Flow

Chapter 25: Spirals, Lunar Cycles, Snake Coils, Hooks and Axes

Chapter 26: Spirals, Whirlpools, Combs, Brushes, and Animal Whirlpools in Opposite Directions

Chapter 27: The Hands and Feet of the Goddess

Chapter 28: The Stone and the Circle

conclusion

The Goddess's Position and Role

Changes in Goddesses During the Indo-European and Christian Eras

The worldview of the goddess tradition

Symbol Glossary

Types of Goddesses and Goddesses

Images and roles of great goddesses/gods of the Neolithic Age

Timeline

map

References

Illustration source

index

Author's Preface

Recommendation for the Korean edition - Kim Jong-il (Professor, Department of Archaeology and Art History, Seoul National University)

Translator's Preface

Category of symbols

Part I: The Gift of Life

Chapter 1: Symbols of the New Goddess: The V-Shaped Pattern and the Wedge Pattern

Chapter 2 Zigzag Pattern and M Pattern

Chapter 3: Meander Patterns and Waterfowl

Chapter 4: The Breasts of the New Goddess

Chapter 5 Wave Pattern

Chapter 6: The Eyes of the Goddess

Chapter 7 Open Mouth/Goddess's Beak

Chapter 8: Grantors of Craft Skills Related to Spinning, Weaving, Metallurgy, and Musical Instruments

Chapter 9: The Ram, the Animal of the New Goddess

Chapter 10: Mesh Pattern

Chapter 11: The Power of the Three Lines and the Number 3

Chapter 12: The Vulva and Birth

Chapter 13: Deer and Bear as Mothers

Chapter 14 The Snake

Part II: Regeneration and the Eternal World

Chapter 15: The Great Mother

Chapter 16: The Power of Two

Chapter 17: The Gods and the Daimons

Part III: Death and Rebirth

Chapter 18: Symbols of Death

Chapter 19 Al

Chapter 20: The Pillars of Life

Chapter 21: Symbols of Regeneration: The Vulva: The Triangle, the Hourglass, and the Bird's Claw

Chapter 22: The Ship of Rebirth

Chapter 23: The Frog, the Hedgehog, and the Fish

Chapter 24: Hydrogen, Bees, and Butterflies

Part IV Energy and Flow

Chapter 25: Spirals, Lunar Cycles, Snake Coils, Hooks and Axes

Chapter 26: Spirals, Whirlpools, Combs, Brushes, and Animal Whirlpools in Opposite Directions

Chapter 27: The Hands and Feet of the Goddess

Chapter 28: The Stone and the Circle

conclusion

The Goddess's Position and Role

Changes in Goddesses During the Indo-European and Christian Eras

The worldview of the goddess tradition

Symbol Glossary

Types of Goddesses and Goddesses

Images and roles of great goddesses/gods of the Neolithic Age

Timeline

map

References

Illustration source

index

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

The purpose of this book is to create an illustrated dictionary of the great goddess religions of Old Europe.

This book is composed of various patterns and images of gods, and these patterns and images serve as key data for reconstructing the landscape of prehistoric times.

This is also an essential resource for correctly understanding Western religion and mythology.

About 20 years ago, I first began to question the meaning of the patterns that recurred on Neolithic European pottery paintings and ceremonial objects.

These patterns were like a giant puzzle, two-thirds of the pieces of which were already missing.

But as the puzzle was completed, the central themes of Old European ideology emerged.

I have primarily worked on analyzing symbols and images and discovering their inherent order, which has led me to understand that the images of artifacts represent the syntax and grammar of a kind of metalanguage.

Gradually, a whole set of meanings began to emerge, this metalanguage expressing the basic worldview of Old European civilization, that is, before Indo-European civilization.

Symbols are never abstract.

Because symbols are always connected to nature, their meaning can be understood through studying their context or associations.

Since the existence of artistic forms expressed in relics is based on mythological thinking, it is possible to decipher the myths of the people of that time in this way.

--- p.xv

Farmers were concerned with the aridity and fertility of the land, the fragility of life and the fear of repeated destruction, and the need for periodic renewal of natural processes of regeneration or reproduction.

This is arguably the longest-lasting belief system in human history.

Although this belief has been constantly diluted and destroyed throughout history, this belief system still survives to this day.

The oldest form of this belief is revealed in the face of prehistoric goddesses, but it is still passed down from grandmother to mother in European villages today.

The ancient belief system went through periods of replacement by Indo-European mythologies and then by periods of dominance by Christian mythologies, but ultimately survived.

Goddess-centered religions have existed on Earth for a very long time.

This religion can never be washed away from the Western mind, as it is much older than the Indo-European or Christian civilizations, which are relatively short periods in human history.

--- p.xvii

The central themes of traditional goddess symbols are birth, death, and rebirth, which emphasize the mystery of life.

Here, life refers not only to humans but also to all life on Earth.

In fact, it encompasses all life in the universe.

The symbols and images represent the Parthenogenetic Goddess, who conceives life without the intervention of a male deity, the giver of life, the giver of death, and equally important, the enabler of rebirth, and are organized around the Earth Mother, the young fertility goddess, the mature fertility goddess, and the goddesses who bring about the birth and death of vegetation.

This symbolic system represents not linear time, but cyclical, mythical time.

In the art of the time, this meaning was expressed through dynamic movement, such as swirling spirals, coiled snakes, circles, crescent moons, horns, and germinating seeds or sprouts.

--- p.xix

Marija Gimbutas's research began in the late 1950s, continued through the 1960s and 1970s, and was completed in the late 1980s.

It is no exaggeration to say that Kimbutas almost single-handedly led research in this field in the 1960s and 1970s, a time when skepticism was widespread regarding the methodologically challenging nature of accessing the mind and spiritual world, as well as the uncertainty surrounding its content. Consequently, more attention was paid to understanding the behavioral patterns of past people.

First published in 1989, 『The Language of the Goddess』, along with 『The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe』, published in 1974, and 『The Civilization of the Goddess』, published in 1991, can be considered a masterpiece that summarizes the remarkable achievements that Gimbutas has accumulated through long-term research.

In particular, 『The Language of the Goddess』, introduced this time, is a book that, unlike other works, organizes and categorizes numerous objects and images excavated from the Middle East, including Eastern Europe, and Southern Europe by major form and interprets them within a consistent framework of goddesses, production and abundance, and death and rebirth.

Therefore, this book is a comprehensive compilation of Kimbutas's long academic journey and achievements, and it is an important work that can be used as a starting point among the must-read books for a more systematic understanding of her other works and for a deeper understanding of the various symbols and signs that appear from the Late Paleolithic to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

--- p.xxi

Kim Butas, who created the art of archaeology, meticulously observed these relics, empathized with them, and used his imagination to infer and analyze them.

It shows that it is possible to reconstruct what an artifact meant to the craftsmen who created it or to our primordial ancestors who used it, through the ability to synthesize patterns or the mastery of understanding symbols.

To this end, I was willing to take the risk of inferring connections between the silent artifacts and the rituals and beliefs of the ancestors who used them.

“If you don’t have a vision, if you’re not a poet or an artist, you won’t see much.” This is the expression of the great scholar Kimbutas.

Kim Butas demonstrates throughout the book his ability to read this metalanguage.

And it teaches us to decipher, read and see the grammar of the language of the goddess.

--- p.xxvi

As this book will reveal, in prehistoric times the image of death was not overshadowed by the image of life.

The image of death is combined with symbols of rebirth, suggesting that the messengers of death or those who govern death always have rebirth in mind.

The existence of this motif can be confirmed by countless artifacts.

An example is an artifact showing the head of a bird of prey placed between the breast, jaws, and teeth of a ferocious boar, with the breast covering it (7th millennium BC, Çatalhüyük Temple, central Turkey).

Also, the Western European owl goddess images decorated on the walls of megalithic tombs or on tombstones depict breasts.

In cases where breasts are not shown, a labyrinth is depicted within the goddess's body to create life, with a vulva depicted in the center of the labyrinth.

--- p.xxviii

One god is the giver of life and at the same time the giver of death.

This interplay of life and death is a key characteristic of the goddesses who were dominant at the time.

The goddess of life and childbirth can transform into a fearsome death-giver, either as a stiff nude or as an image of a supernatural womb-shaped triangle carved into bone.

This triangle in the uterine area is where the transformation from death to new life begins.

Sometimes, statues of bird goddesses with new masks and birds of prey are observed, which shows the relationship between the goddess and birds of prey.

Also, the snake goddess with a long mouth, sharp fangs, and small round eyes is associated with venomous snakes.

Although the stiff nude figurines excavated from the Late Paleolithic sites do not exhibit the raised parts that give rise to life, they are the ancestors of the stiff nude figurines that appear in Old Europe.

The materials of old European nude statues were marble, plaster, or light-colored stone or bone, the colors of death.

--- p.xxix

Throughout Europe, especially in the west and north, large boulders and human-shaped stones that have been deliberately deformed are observed.

A striking feature of these boulders is the presence of small, round holes called sunghyeol.

The number of holes varies from one to hundreds.

These holes sometimes appear with eye or snake motifs.

Often, these patterns are adorned on human-shaped stones, that is, statues of goddesses (Figure 98).

It is not uncommon for one, two or more circles to surround it.

These holes clearly represent eyes, and naturally they signify the source of the divine water, the water of life itself.

It is also a container that holds running water.

Some of this symbolic meaning still remains among European peasants today.

Farmers believe in the healing power of rainwater and still collect rainwater collected in Seonghyeol.

People who are paralyzed or disabled drink the sacred water, wash themselves with it, and apply it to problem areas.

For example, the Greeks perform the Paraskevi ritual on Good Friday, July 26th.

It is a ritual that inherits the tradition of prehistoric goddesses, and Paraskevi is believed to be particularly effective in curing eye diseases.

During this ritual, hundreds of silver offerings symbolizing human eyes are made to adorn the icon of the goddess (Megas 1963: 144). I witnessed these offerings adorning a portrait of a saint in a temple on the island of Paros in the middle of the Aegean Sea in the summer of 1986.

--- p.61

From prehistoric times to the present day, owls have been considered omens of death.

In many European countries, it is still believed today that if an owl lands on a roof or a tree near a house, the family will die.

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the owl also signifies death.

Even in the time of Pliny the Great in the 1st century AD, it was believed that the appearance of an owl in a city meant destruction.

Later writers also described owls as ominous, unpleasant, and tragic, and there are statements that other birds disliked them.

Even in the early 18th century, the owl was recognized as a powerful symbol of death.

Spencer once described owls as cruel messengers of death, feared and loathed by humans (Rowland 1978: 119).

Despite this gloomy image surrounding owls, there was a positive side.

Owls were believed to possess profound wisdom, the power of oracles, and the power to ward off evil.

It was believed that some divine power was especially present in the eyes of owls, perhaps because their keen eyesight was superior to that of other creatures.

This dual image is a remnant of the notion that the owl embodies the cruel goddess of death, which has faded over time.

Owls were worshipped as gods.

Perhaps it was because they were considered a cruel but indispensable part of the overall cycle of life that they became objects of worship.

--- p.190

The images and symbols presented in this book are an archaeological record of the ancient world that argues that the era of the goddess, who produced offspring without the intervention of a male god, was one of the most enduring traits in human history.

In Europe, the goddess dominated the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods, and in the Mediterranean this tradition continued until most of the Bronze Age.

Then comes the era of priests and patriarchal warrior gods.

They replaced or assimilated the goddesses or mother gods of the gods.

This is an intermediate stage before the philosophical rejection of Christianity and the ancient goddess traditions expanded.

Gradually, a prejudice against things belonging to the earth develops.

Along with this, all goddesses and anything symbolizing the goddess are rejected.

The goddesses gradually retreated into the deep forests or mountaintops.

They survived in this place and their existence is passed down today in the form of folk beliefs and old tales.

Humans have become increasingly alienated from their living roots in earth-centered life.

The society we live in today clearly testifies to the results that have resulted.

But the rhythm of nature never stops.

Now that the goddesses are reappearing in the forests and mountains, we can dream of hope.

This phenomenon takes us back to the most ancient roots of humanity.

This book is composed of various patterns and images of gods, and these patterns and images serve as key data for reconstructing the landscape of prehistoric times.

This is also an essential resource for correctly understanding Western religion and mythology.

About 20 years ago, I first began to question the meaning of the patterns that recurred on Neolithic European pottery paintings and ceremonial objects.

These patterns were like a giant puzzle, two-thirds of the pieces of which were already missing.

But as the puzzle was completed, the central themes of Old European ideology emerged.

I have primarily worked on analyzing symbols and images and discovering their inherent order, which has led me to understand that the images of artifacts represent the syntax and grammar of a kind of metalanguage.

Gradually, a whole set of meanings began to emerge, this metalanguage expressing the basic worldview of Old European civilization, that is, before Indo-European civilization.

Symbols are never abstract.

Because symbols are always connected to nature, their meaning can be understood through studying their context or associations.

Since the existence of artistic forms expressed in relics is based on mythological thinking, it is possible to decipher the myths of the people of that time in this way.

--- p.xv

Farmers were concerned with the aridity and fertility of the land, the fragility of life and the fear of repeated destruction, and the need for periodic renewal of natural processes of regeneration or reproduction.

This is arguably the longest-lasting belief system in human history.

Although this belief has been constantly diluted and destroyed throughout history, this belief system still survives to this day.

The oldest form of this belief is revealed in the face of prehistoric goddesses, but it is still passed down from grandmother to mother in European villages today.

The ancient belief system went through periods of replacement by Indo-European mythologies and then by periods of dominance by Christian mythologies, but ultimately survived.

Goddess-centered religions have existed on Earth for a very long time.

This religion can never be washed away from the Western mind, as it is much older than the Indo-European or Christian civilizations, which are relatively short periods in human history.

--- p.xvii

The central themes of traditional goddess symbols are birth, death, and rebirth, which emphasize the mystery of life.

Here, life refers not only to humans but also to all life on Earth.

In fact, it encompasses all life in the universe.

The symbols and images represent the Parthenogenetic Goddess, who conceives life without the intervention of a male deity, the giver of life, the giver of death, and equally important, the enabler of rebirth, and are organized around the Earth Mother, the young fertility goddess, the mature fertility goddess, and the goddesses who bring about the birth and death of vegetation.

This symbolic system represents not linear time, but cyclical, mythical time.

In the art of the time, this meaning was expressed through dynamic movement, such as swirling spirals, coiled snakes, circles, crescent moons, horns, and germinating seeds or sprouts.

--- p.xix

Marija Gimbutas's research began in the late 1950s, continued through the 1960s and 1970s, and was completed in the late 1980s.

It is no exaggeration to say that Kimbutas almost single-handedly led research in this field in the 1960s and 1970s, a time when skepticism was widespread regarding the methodologically challenging nature of accessing the mind and spiritual world, as well as the uncertainty surrounding its content. Consequently, more attention was paid to understanding the behavioral patterns of past people.

First published in 1989, 『The Language of the Goddess』, along with 『The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe』, published in 1974, and 『The Civilization of the Goddess』, published in 1991, can be considered a masterpiece that summarizes the remarkable achievements that Gimbutas has accumulated through long-term research.

In particular, 『The Language of the Goddess』, introduced this time, is a book that, unlike other works, organizes and categorizes numerous objects and images excavated from the Middle East, including Eastern Europe, and Southern Europe by major form and interprets them within a consistent framework of goddesses, production and abundance, and death and rebirth.

Therefore, this book is a comprehensive compilation of Kimbutas's long academic journey and achievements, and it is an important work that can be used as a starting point among the must-read books for a more systematic understanding of her other works and for a deeper understanding of the various symbols and signs that appear from the Late Paleolithic to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

--- p.xxi

Kim Butas, who created the art of archaeology, meticulously observed these relics, empathized with them, and used his imagination to infer and analyze them.

It shows that it is possible to reconstruct what an artifact meant to the craftsmen who created it or to our primordial ancestors who used it, through the ability to synthesize patterns or the mastery of understanding symbols.

To this end, I was willing to take the risk of inferring connections between the silent artifacts and the rituals and beliefs of the ancestors who used them.

“If you don’t have a vision, if you’re not a poet or an artist, you won’t see much.” This is the expression of the great scholar Kimbutas.

Kim Butas demonstrates throughout the book his ability to read this metalanguage.

And it teaches us to decipher, read and see the grammar of the language of the goddess.

--- p.xxvi

As this book will reveal, in prehistoric times the image of death was not overshadowed by the image of life.

The image of death is combined with symbols of rebirth, suggesting that the messengers of death or those who govern death always have rebirth in mind.

The existence of this motif can be confirmed by countless artifacts.

An example is an artifact showing the head of a bird of prey placed between the breast, jaws, and teeth of a ferocious boar, with the breast covering it (7th millennium BC, Çatalhüyük Temple, central Turkey).

Also, the Western European owl goddess images decorated on the walls of megalithic tombs or on tombstones depict breasts.

In cases where breasts are not shown, a labyrinth is depicted within the goddess's body to create life, with a vulva depicted in the center of the labyrinth.

--- p.xxviii

One god is the giver of life and at the same time the giver of death.

This interplay of life and death is a key characteristic of the goddesses who were dominant at the time.

The goddess of life and childbirth can transform into a fearsome death-giver, either as a stiff nude or as an image of a supernatural womb-shaped triangle carved into bone.

This triangle in the uterine area is where the transformation from death to new life begins.

Sometimes, statues of bird goddesses with new masks and birds of prey are observed, which shows the relationship between the goddess and birds of prey.

Also, the snake goddess with a long mouth, sharp fangs, and small round eyes is associated with venomous snakes.

Although the stiff nude figurines excavated from the Late Paleolithic sites do not exhibit the raised parts that give rise to life, they are the ancestors of the stiff nude figurines that appear in Old Europe.

The materials of old European nude statues were marble, plaster, or light-colored stone or bone, the colors of death.

--- p.xxix

Throughout Europe, especially in the west and north, large boulders and human-shaped stones that have been deliberately deformed are observed.

A striking feature of these boulders is the presence of small, round holes called sunghyeol.

The number of holes varies from one to hundreds.

These holes sometimes appear with eye or snake motifs.

Often, these patterns are adorned on human-shaped stones, that is, statues of goddesses (Figure 98).

It is not uncommon for one, two or more circles to surround it.

These holes clearly represent eyes, and naturally they signify the source of the divine water, the water of life itself.

It is also a container that holds running water.

Some of this symbolic meaning still remains among European peasants today.

Farmers believe in the healing power of rainwater and still collect rainwater collected in Seonghyeol.

People who are paralyzed or disabled drink the sacred water, wash themselves with it, and apply it to problem areas.

For example, the Greeks perform the Paraskevi ritual on Good Friday, July 26th.

It is a ritual that inherits the tradition of prehistoric goddesses, and Paraskevi is believed to be particularly effective in curing eye diseases.

During this ritual, hundreds of silver offerings symbolizing human eyes are made to adorn the icon of the goddess (Megas 1963: 144). I witnessed these offerings adorning a portrait of a saint in a temple on the island of Paros in the middle of the Aegean Sea in the summer of 1986.

--- p.61

From prehistoric times to the present day, owls have been considered omens of death.

In many European countries, it is still believed today that if an owl lands on a roof or a tree near a house, the family will die.

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, the owl also signifies death.

Even in the time of Pliny the Great in the 1st century AD, it was believed that the appearance of an owl in a city meant destruction.

Later writers also described owls as ominous, unpleasant, and tragic, and there are statements that other birds disliked them.

Even in the early 18th century, the owl was recognized as a powerful symbol of death.

Spencer once described owls as cruel messengers of death, feared and loathed by humans (Rowland 1978: 119).

Despite this gloomy image surrounding owls, there was a positive side.

Owls were believed to possess profound wisdom, the power of oracles, and the power to ward off evil.

It was believed that some divine power was especially present in the eyes of owls, perhaps because their keen eyesight was superior to that of other creatures.

This dual image is a remnant of the notion that the owl embodies the cruel goddess of death, which has faded over time.

Owls were worshipped as gods.

Perhaps it was because they were considered a cruel but indispensable part of the overall cycle of life that they became objects of worship.

--- p.190

The images and symbols presented in this book are an archaeological record of the ancient world that argues that the era of the goddess, who produced offspring without the intervention of a male god, was one of the most enduring traits in human history.

In Europe, the goddess dominated the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods, and in the Mediterranean this tradition continued until most of the Bronze Age.

Then comes the era of priests and patriarchal warrior gods.

They replaced or assimilated the goddesses or mother gods of the gods.

This is an intermediate stage before the philosophical rejection of Christianity and the ancient goddess traditions expanded.

Gradually, a prejudice against things belonging to the earth develops.

Along with this, all goddesses and anything symbolizing the goddess are rejected.

The goddesses gradually retreated into the deep forests or mountaintops.

They survived in this place and their existence is passed down today in the form of folk beliefs and old tales.

Humans have become increasingly alienated from their living roots in earth-centered life.

The society we live in today clearly testifies to the results that have resulted.

But the rhythm of nature never stops.

Now that the goddesses are reappearing in the forests and mountains, we can dream of hope.

This phenomenon takes us back to the most ancient roots of humanity.

--- p.321

Publisher's Review

“The primordial gods were goddesses.

Do you remember?

A classic of mythology that awakens the lost goddess deep within the unconscious.

“The message emphasized in this book is that before the short 5,000-year history of mankind, which James Joyce diagnosed as a ‘nightmare,’ there actually existed a 4,000-year history that was completely different from the present.

This period was a time of harmony and peace, in keeping with the creative energy of nature.

Now, it is time for the whole Earth to wake up from this ‘nightmare.’”

-From Joseph Campbell's recommendation

The book 『The Language of the Goddess』, which received numerous requests for republication from readers, has been republished.

This book is a unique and monumental work that illuminates the religion, society, ideology, and culture of prehistoric times before the establishment of patriarchy. It caused a sensation when it was published in 1989 and has since influenced various ideologies, research, and cultural content.

In Western civilization, which traces its origins to ancient Greece, the fact that a matriarchal society centered on a goddess existed first and the vast amount of artifacts supporting this were truly shocking events.

Author Marija Gimbutas, who began her career as an archaeologist at Harvard University, was the only female archaeologist on campus at the time.

He studied the culture of war for over ten years, classifying various weapon relics in accordance with the academic tradition and trend, and began to question the perspective that explained humanity through the logic of 'war' and 'domination'.

"Was war truly inevitable throughout human history? And where are women in that history? Has men dominated women throughout human civilization?" This is why he turned his gaze to prehistoric times.

In the following decades, he became increasingly dedicated to excavating artifacts from the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and through interdisciplinary research encompassing comparative mythology, early historical sources, linguistics, ethnography, and folklore, he devoted himself to analyzing the symbols and meanings of the patterns engraved on the artifacts and discovering their inherent order.

As a result, it was revealed that goddess worship and an earth-centered culture existed in the life of human communities before patriarchy.

The ancient matriarchal society, as interpreted by thousands of relic icons, was characterized by “equality rather than hierarchy, presence rather than transcendence, diversity rather than unity, rhythm and change rather than stillness and fixation, harmony rather than dominance and domination” (p. xxvi).

Before Kimbutas, historian Bachofen (1815-1887) had also argued for a matriarchal society in the early days of mankind.

However, Kim Butas's perspective was different.

While Bachoffen viewed the transition from a matriarchal society to a patriarchal society as the evolution of humanity, Gimbutas argued that male-centered civilization was rather temporary in the long history of humanity, and that the culture of war and domination derived from it was merely a pathological phenomenon (p. xxv). He argued that humanity lived peacefully without war for a longer period before historical times, and traces of the goddess tradition prove this.

Although this was a topic that was difficult to accept in the existing academic world, which was male-centered and centered on written records, research on goddesses began to gain momentum in the academic world in the 1970s.

In particular, attempts to shift the focus of research to prehistoric times continued, with awareness of the problem that even images of goddesses from historical times were influenced by patriarchy.

All of this work was based on Kim Butas' research, which began in the 1950s.

Scholars such as Joseph Campbell and Leonard Schlane have stated that their research on the goddesses of primitive humans was entirely based on Gimbutas's work, and Gloria Steinem, a leader in the second wave of feminism, and psychoanalyst Jean Shinoda Bolin also highly regarded Gimbutas's work.

The attempts widely attempted today to reinterpret mythological goddesses by giving them more subjective narratives rather than referring to them as the mother, wife, or daughter of a male god would also have been impossible without Kimbutas's achievements.

About 2,000 relics are being restored

Goddess civilization society 10,000 years ago

Ninety percent of the statues of gods in prehistoric times (especially up to the Neolithic Age) were goddess statues.

The Venus of Willendorf, widely considered the oldest human-figure sculpture, also dates from this period.

Unlike previous discussions that limited the meaning of the goddess to abundance and fertility, the main themes of the symbols of this period, which Kimbutas revealed had affinities with all things in nature, including the earth and the moon, were birth, death (destruction), and rebirth.

Life and birth are also important themes in goddess culture, but he argues that explaining the goddess's power solely through motherhood is a perspective that narrowly interprets the goddess (femininity) of the time.

In this world, there is no hierarchy between birth and death, and goddesses conceive life and bring about death on their own without the intervention of male gods.

Black, the color of the soil and the womb, is associated with vitality, while white, the color of bones, signifies death and destruction.

The goddesses bring good luck, give prophecies, howl like birds of prey, and crawl like venomous snakes.

This is a characteristic that clearly distinguishes it from the worldview of the Indo-European civilization, which clearly divides the heaven and the underworld into hierarchies and interprets the meaning of the goddess only in terms of motherhood and altruism.

It is a temporality that is different from today's linear concept of time, which begins with life and ends with death.

The 2,000 or so artifacts featured in the book include ancient funerary objects, sculptures, figurines, frescoes, sacrificial vessels, and pottery excavated from temples, shrines, and tombs.

The objects and images of artifacts excavated from Europe and the Middle East during the Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Ages were classified into 28 shapes, including waves, wedges, triangles, zigzags, V-shapes, M-shapes, and shapes of birds, snakes, sheep, and bears, and were further divided into four themes: life, regeneration, death and rebirth, and energy and flow.

The appendix includes a glossary of symbolic terms, types of goddesses and gods and their roles, a chronology, a map of artifact excavation sites, and an index, helping readers to learn the grammar of the goddess's language from various perspectives.

In keeping with the author's definition of this book as a 'dictionary of goddess religions,' it features a clear and friendly structure.

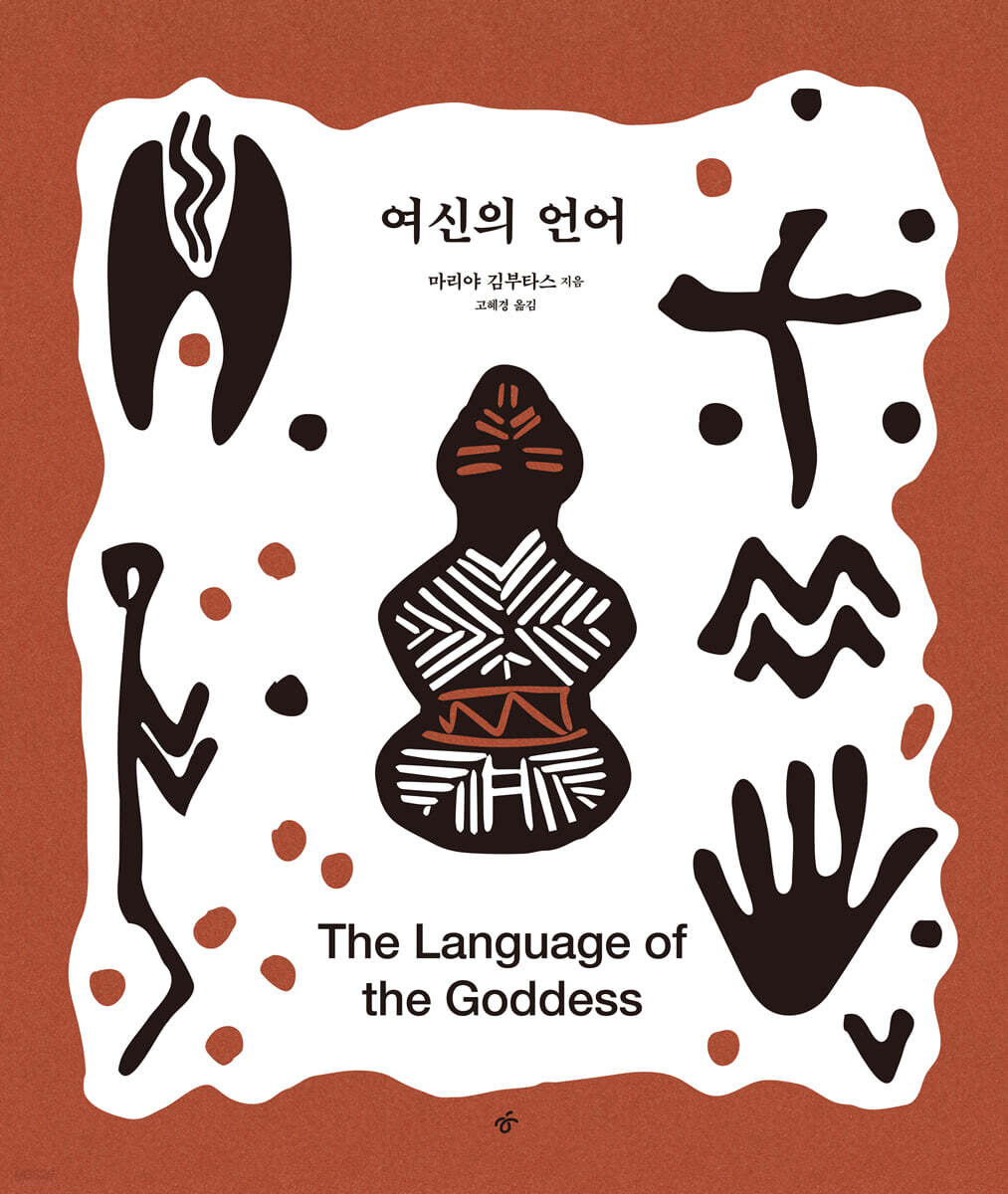

In particular, the revised edition retains the large first edition format of 250*300mm, while the binding and cover design capture the texture and color of terracotta pottery, a representative artifact of the period, allowing readers to experience the book more synesthetically.

Guided by the author's emphasis on "intuition" and "spirituality" as reading tips, "The Language of the Goddess" will lead you beyond the acquisition of knowledge and into an experience of encountering the goddess latent within you.

“This book brilliantly restores the language of a goddess who does not submit to power, a goddess who dreams of beauty, acceptance, and healing rather than power, thereby awakening us to the fact that the ‘lost paradise of goddesses’ already lives vividly deep within our subconscious.

The moment you truly understand this book, you will be able to listen to the breath of the Great Goddess and feel the lost energy of the Anima (unconscious feminine) awakening within you.”

- From the recommendation of author Jeong Yeo-ul

In an age of war and climate crisis

Rereading this book

Kimbutas's claim that there was no war in 'Old Europe' sparks heated debate.

How would Kimbutas have interpreted the statistic that throughout human history, there have been only three days on Earth without war? To us, who still experience war on a daily basis, his story certainly sounds somewhat unrealistic.

However, it is archaeologically proven that people during this period, even after they mastered metallurgy, did not create lethal weapons of mass destruction, and that they did not build defensive structures even in large villages.

Kimbutas explains that in an agricultural society where raising and caring for livestock and food was important, peace and equality were of paramount importance.

His argument is that after this goddess-centered egalitarian society collapsed due to the invasion of the nomadic Kurgan people, an authoritarian patriarchal system centered on the "father god" was established, and in the process, the goddesses barely managed to survive as wives or daughters of warlike male gods, and even then, they were pushed to the periphery after the advent of Christianity.

It is difficult to determine the truth of the 'era without war'.

However, following the view of anthropologist Pierre Clastres, who viewed myths not as reflections of reality but rather attempts to modify it, we could also view the goddess movement as a practice aimed at creating a new cultural order in the present context.

In the midst of war and the climate crisis, I hope this book connects us with the language of peace and equality.

Do you remember?

A classic of mythology that awakens the lost goddess deep within the unconscious.

“The message emphasized in this book is that before the short 5,000-year history of mankind, which James Joyce diagnosed as a ‘nightmare,’ there actually existed a 4,000-year history that was completely different from the present.

This period was a time of harmony and peace, in keeping with the creative energy of nature.

Now, it is time for the whole Earth to wake up from this ‘nightmare.’”

-From Joseph Campbell's recommendation

The book 『The Language of the Goddess』, which received numerous requests for republication from readers, has been republished.

This book is a unique and monumental work that illuminates the religion, society, ideology, and culture of prehistoric times before the establishment of patriarchy. It caused a sensation when it was published in 1989 and has since influenced various ideologies, research, and cultural content.

In Western civilization, which traces its origins to ancient Greece, the fact that a matriarchal society centered on a goddess existed first and the vast amount of artifacts supporting this were truly shocking events.

Author Marija Gimbutas, who began her career as an archaeologist at Harvard University, was the only female archaeologist on campus at the time.

He studied the culture of war for over ten years, classifying various weapon relics in accordance with the academic tradition and trend, and began to question the perspective that explained humanity through the logic of 'war' and 'domination'.

"Was war truly inevitable throughout human history? And where are women in that history? Has men dominated women throughout human civilization?" This is why he turned his gaze to prehistoric times.

In the following decades, he became increasingly dedicated to excavating artifacts from the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages, and through interdisciplinary research encompassing comparative mythology, early historical sources, linguistics, ethnography, and folklore, he devoted himself to analyzing the symbols and meanings of the patterns engraved on the artifacts and discovering their inherent order.

As a result, it was revealed that goddess worship and an earth-centered culture existed in the life of human communities before patriarchy.

The ancient matriarchal society, as interpreted by thousands of relic icons, was characterized by “equality rather than hierarchy, presence rather than transcendence, diversity rather than unity, rhythm and change rather than stillness and fixation, harmony rather than dominance and domination” (p. xxvi).

Before Kimbutas, historian Bachofen (1815-1887) had also argued for a matriarchal society in the early days of mankind.

However, Kim Butas's perspective was different.

While Bachoffen viewed the transition from a matriarchal society to a patriarchal society as the evolution of humanity, Gimbutas argued that male-centered civilization was rather temporary in the long history of humanity, and that the culture of war and domination derived from it was merely a pathological phenomenon (p. xxv). He argued that humanity lived peacefully without war for a longer period before historical times, and traces of the goddess tradition prove this.

Although this was a topic that was difficult to accept in the existing academic world, which was male-centered and centered on written records, research on goddesses began to gain momentum in the academic world in the 1970s.

In particular, attempts to shift the focus of research to prehistoric times continued, with awareness of the problem that even images of goddesses from historical times were influenced by patriarchy.

All of this work was based on Kim Butas' research, which began in the 1950s.

Scholars such as Joseph Campbell and Leonard Schlane have stated that their research on the goddesses of primitive humans was entirely based on Gimbutas's work, and Gloria Steinem, a leader in the second wave of feminism, and psychoanalyst Jean Shinoda Bolin also highly regarded Gimbutas's work.

The attempts widely attempted today to reinterpret mythological goddesses by giving them more subjective narratives rather than referring to them as the mother, wife, or daughter of a male god would also have been impossible without Kimbutas's achievements.

About 2,000 relics are being restored

Goddess civilization society 10,000 years ago

Ninety percent of the statues of gods in prehistoric times (especially up to the Neolithic Age) were goddess statues.

The Venus of Willendorf, widely considered the oldest human-figure sculpture, also dates from this period.

Unlike previous discussions that limited the meaning of the goddess to abundance and fertility, the main themes of the symbols of this period, which Kimbutas revealed had affinities with all things in nature, including the earth and the moon, were birth, death (destruction), and rebirth.

Life and birth are also important themes in goddess culture, but he argues that explaining the goddess's power solely through motherhood is a perspective that narrowly interprets the goddess (femininity) of the time.

In this world, there is no hierarchy between birth and death, and goddesses conceive life and bring about death on their own without the intervention of male gods.

Black, the color of the soil and the womb, is associated with vitality, while white, the color of bones, signifies death and destruction.

The goddesses bring good luck, give prophecies, howl like birds of prey, and crawl like venomous snakes.

This is a characteristic that clearly distinguishes it from the worldview of the Indo-European civilization, which clearly divides the heaven and the underworld into hierarchies and interprets the meaning of the goddess only in terms of motherhood and altruism.

It is a temporality that is different from today's linear concept of time, which begins with life and ends with death.

The 2,000 or so artifacts featured in the book include ancient funerary objects, sculptures, figurines, frescoes, sacrificial vessels, and pottery excavated from temples, shrines, and tombs.

The objects and images of artifacts excavated from Europe and the Middle East during the Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Ages were classified into 28 shapes, including waves, wedges, triangles, zigzags, V-shapes, M-shapes, and shapes of birds, snakes, sheep, and bears, and were further divided into four themes: life, regeneration, death and rebirth, and energy and flow.

The appendix includes a glossary of symbolic terms, types of goddesses and gods and their roles, a chronology, a map of artifact excavation sites, and an index, helping readers to learn the grammar of the goddess's language from various perspectives.

In keeping with the author's definition of this book as a 'dictionary of goddess religions,' it features a clear and friendly structure.

In particular, the revised edition retains the large first edition format of 250*300mm, while the binding and cover design capture the texture and color of terracotta pottery, a representative artifact of the period, allowing readers to experience the book more synesthetically.

Guided by the author's emphasis on "intuition" and "spirituality" as reading tips, "The Language of the Goddess" will lead you beyond the acquisition of knowledge and into an experience of encountering the goddess latent within you.

“This book brilliantly restores the language of a goddess who does not submit to power, a goddess who dreams of beauty, acceptance, and healing rather than power, thereby awakening us to the fact that the ‘lost paradise of goddesses’ already lives vividly deep within our subconscious.

The moment you truly understand this book, you will be able to listen to the breath of the Great Goddess and feel the lost energy of the Anima (unconscious feminine) awakening within you.”

- From the recommendation of author Jeong Yeo-ul

In an age of war and climate crisis

Rereading this book

Kimbutas's claim that there was no war in 'Old Europe' sparks heated debate.

How would Kimbutas have interpreted the statistic that throughout human history, there have been only three days on Earth without war? To us, who still experience war on a daily basis, his story certainly sounds somewhat unrealistic.

However, it is archaeologically proven that people during this period, even after they mastered metallurgy, did not create lethal weapons of mass destruction, and that they did not build defensive structures even in large villages.

Kimbutas explains that in an agricultural society where raising and caring for livestock and food was important, peace and equality were of paramount importance.

His argument is that after this goddess-centered egalitarian society collapsed due to the invasion of the nomadic Kurgan people, an authoritarian patriarchal system centered on the "father god" was established, and in the process, the goddesses barely managed to survive as wives or daughters of warlike male gods, and even then, they were pushed to the periphery after the advent of Christianity.

It is difficult to determine the truth of the 'era without war'.

However, following the view of anthropologist Pierre Clastres, who viewed myths not as reflections of reality but rather attempts to modify it, we could also view the goddess movement as a practice aimed at creating a new cultural order in the present context.

In the midst of war and the climate crisis, I hope this book connects us with the language of peace and equality.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 18, 2024

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 416 pages | 2,304g | 250*300*40mm

- ISBN13: 9791172131364

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)