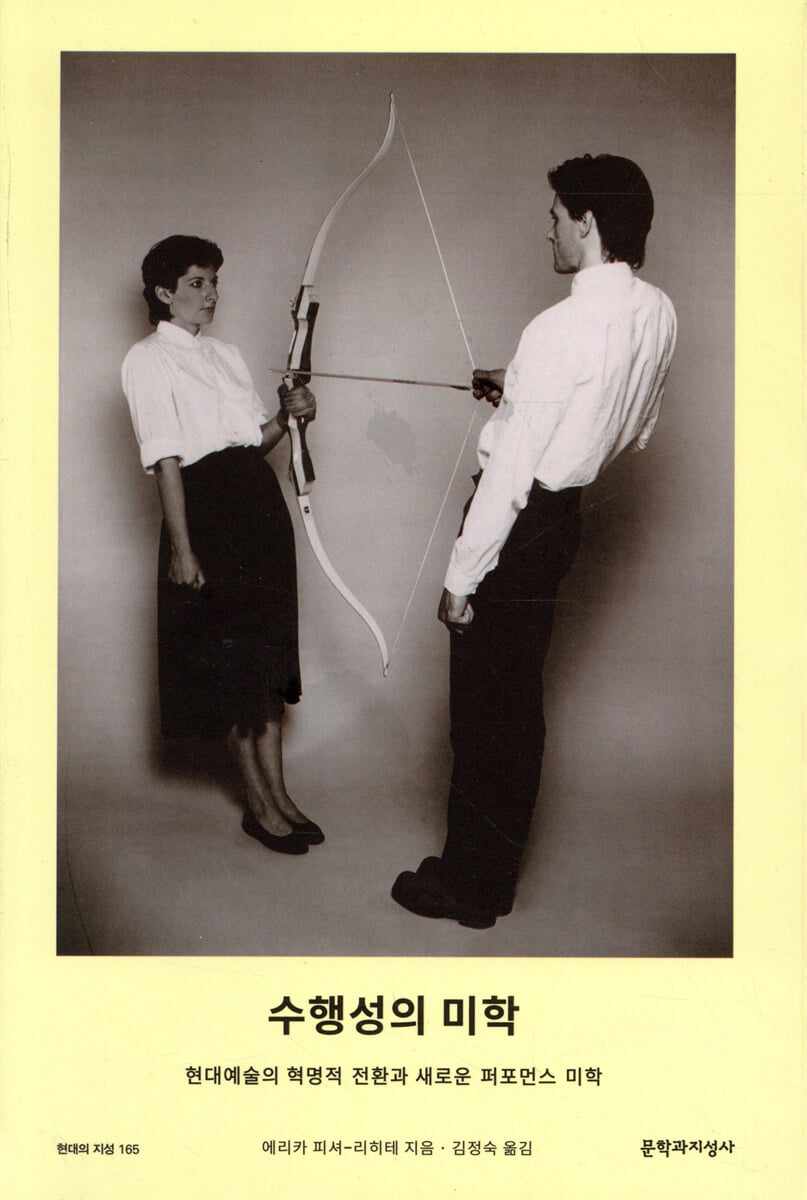

The aesthetics of performativity

|

Description

Book Introduction

An artist who beats himself with a whip and cuts his stomach with a razor blade.

A pianist who sits at the piano and doesn't play a single note

Actors who hurled insults at the audience or harassed them while blindfolded… …

Breaking down the boundaries between audience and actor, body and mind, life and art

The performative shift in contemporary art and the advent of a new aesthetic

An interesting incident occurred during the performance of "Tomas's Lips" by performance artist Marina Abramović in 1975.

The artist sat naked, swallowed over a kilogram of honey and wine, then carved a star shape on his stomach with a razor blade and whipped his back before being dragged down by the audience to lie on an ice cross.

It was a kind of incident where the audience who was watching the artist perform an intended action intervened.

The dichotomous thinking that the artist is the subject who creates the work and the audience is the object who passively receives it can no longer be maintained.

In many performances, the audience does not just engage in conventional actions like clapping, but actually participates with as much rights as the actors.

Today, new genres of performing arts are proliferating, shaking up existing values and norms and creating events that draw audiences in, and the relationship between audience and artist is also changing accordingly.

In this changing artistic environment, where the boundaries between art and life, aesthetics and ethics have collapsed and the distinctions between producers, recipients, and works of art have become unclear, contemporary art cannot be accurately explained solely through traditional aesthetic theories, and it even seems anachronistic.

In order to sensitively observe, study, and explain the performative shift in art from the concept of artwork to the concept of event since the 1960s, the emergence of a new aesthetic theory was inevitable.

And at the center of it all is this book, “The Aesthetics of Performance.”

A pianist who sits at the piano and doesn't play a single note

Actors who hurled insults at the audience or harassed them while blindfolded… …

Breaking down the boundaries between audience and actor, body and mind, life and art

The performative shift in contemporary art and the advent of a new aesthetic

An interesting incident occurred during the performance of "Tomas's Lips" by performance artist Marina Abramović in 1975.

The artist sat naked, swallowed over a kilogram of honey and wine, then carved a star shape on his stomach with a razor blade and whipped his back before being dragged down by the audience to lie on an ice cross.

It was a kind of incident where the audience who was watching the artist perform an intended action intervened.

The dichotomous thinking that the artist is the subject who creates the work and the audience is the object who passively receives it can no longer be maintained.

In many performances, the audience does not just engage in conventional actions like clapping, but actually participates with as much rights as the actors.

Today, new genres of performing arts are proliferating, shaking up existing values and norms and creating events that draw audiences in, and the relationship between audience and artist is also changing accordingly.

In this changing artistic environment, where the boundaries between art and life, aesthetics and ethics have collapsed and the distinctions between producers, recipients, and works of art have become unclear, contemporary art cannot be accurately explained solely through traditional aesthetic theories, and it even seems anachronistic.

In order to sensitively observe, study, and explain the performative shift in art from the concept of artwork to the concept of event since the 1960s, the emergence of a new aesthetic theory was inevitable.

And at the center of it all is this book, “The Aesthetics of Performance.”

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Korean edition

Chapter 1: Why is the Aesthetics of Performance Necessary?

Chapter 2: Concept Explanation

1.

Performance

2.

performance

Chapter 3: Physical Co-Presence of Actor and Audience

1.

Role reversal

2.

community

3.

contact

4.

Liveness

Chapter 4: The Performative Creation of Materiality

1.

physicality

Embodiment | Presence | Animal? Body

2.

Spatiality

Performative space | Atmosphere

3.

Sound

Auditory Space | Voice

4.

Temporality

Time Bracket | Rhythm

Chapter 5: The Emergence of Meaning

1.

Materiality, signifier, signified

2.

'Presence' and 'Representation'

3.

Meaning and influence

4.

Can you understand the performance?

Chapter 6 Performance as an Event

1.

Automorphism and emergence

2.

Collapsing opposition

3.

Threshold and Transformation

Chapter 7: Reenchanting the World

1.

'production'

2.

'Aesthetic Experience'

3.

Art and Life

References

Translator's Note

Search (person name)

Find (concept)

Chapter 1: Why is the Aesthetics of Performance Necessary?

Chapter 2: Concept Explanation

1.

Performance

2.

performance

Chapter 3: Physical Co-Presence of Actor and Audience

1.

Role reversal

2.

community

3.

contact

4.

Liveness

Chapter 4: The Performative Creation of Materiality

1.

physicality

Embodiment | Presence | Animal? Body

2.

Spatiality

Performative space | Atmosphere

3.

Sound

Auditory Space | Voice

4.

Temporality

Time Bracket | Rhythm

Chapter 5: The Emergence of Meaning

1.

Materiality, signifier, signified

2.

'Presence' and 'Representation'

3.

Meaning and influence

4.

Can you understand the performance?

Chapter 6 Performance as an Event

1.

Automorphism and emergence

2.

Collapsing opposition

3.

Threshold and Transformation

Chapter 7: Reenchanting the World

1.

'production'

2.

'Aesthetic Experience'

3.

Art and Life

References

Translator's Note

Search (person name)

Find (concept)

Into the book

In fact, Abramovich inflicted serious injuries on himself and attempted to continue to torture and abuse him.

If she had performed this act in any other public place, people would have had no hesitation in trying to stop her.

But what about this? If an artist is about to perform an act that seems deliberately planned, shouldn't we respect it? To interrupt it would be to risk damaging the "work" itself. But from a human perspective, is it acceptable to simply watch self-harm? Was the artist intending to invite the audience into the role of voyeur? Or was the artist experimenting with how long it would take for the audience to take action to end the performer's suffering? What is the right decision here? Through this performance, Abramović created a situation that forces the audience into a state of in-between art and everyday life, aesthetics and ethical norms.

(Chapter 1, “Why is the Aesthetics of Performance Necessary?”, p. 18)

For a performance to take place, the performers and the audience must gather at a specific place at a specific time and do something together.

Hermann defined it as “a play by everyone for everyone.”

Through this, he fundamentally redefined the relationship between actor and audience.

Until now, we have not thought of the audience as anything more than observers of the action taking place on stage.

[… … ] However, a performance is not a subject/object relationship in which the audience perceives the actor as an object of observation, nor is it a relationship in which the actor regards himself as a subject and the audience as an object, without exchanging meaning.

The physical co-presence of the actor and the audience is rather a relationship of co-subjectivity.

[… … ] In other words, a performance takes place between the performer and the audience and is co-created by them.

(Chapter 2, “Concept Explanation,” p. 63)

In "Dionysus 69" there is a scene that Schechner calls "the caressing god."

Here, the performers, the performance artists, go next to the audience, squat down or lie down, and begin to caress the audience.

They wore revealing clothing, especially bikini swimsuits for the women.

Audience reactions were varied.

Some audience members, especially the women, quietly and passively enjoyed the gentleness of the caresses.

Conversely, other audience members, mostly male, actively responded to this caressing, touching body parts that the performance artist had deliberately avoided.

The audience ignored the rules and regulations laid down by the artist in advance and accepted the situation as a real situation, not a 'play' about intimacy.

[… … ] What is clear here is that the actor intended to shake up and dismantle the dichotomous relationship between reality and fiction, publicness and intimacy, through contact, and in this way, to lead the audience into a familiar realm and provide them with a new experience.

However, the audience rather understood this act of contact dichotomously.

(Chapter 3, “Physical Co-Presence of Actor and Audience,” pp. 137–38)

Regardless of how or where they each moved, where they looked each time, whether they wore headphones or not, whether the actors' voices penetrated their ears through the headphones, or whether the voices gradually became inaudible as the chaotic voices and the noise of the shopping mall stores mixed together, it became impossible to distinguish between the actors in the theater and the passersby, and the busy movements of the shopping mall and the actors' actions continued to accumulate and overlap in new ways, creating a different spatiality each time.

This principle of creating spatiality was also applied in a significantly modified form of audio tour devised by the 'Hygiene Today' group.

(Chapter 4, “The Performative Creation of Materiality,” pp. 252–53)

The smell of food or drinks causes people to salivate when they breathe in and also affects the internal organs, resulting in strong appetite or disgust.

In this way, the audience who smells becomes aware of their own internal processes and realizes that they are a living organism.

Without a doubt, smell is the most powerful element in creating atmosphere.

This also relates to the fact that once a smell has spread, it can never be 'collected again'.

The resistance is also very strong.

Even when the smoke completely disappears, the smell remains and torments the audience.

Even when the charred eggs completely disappear from the stage, their smell still lingers in the space.

[… … ] The smell persists in attempting to fundamentally change the atmosphere, beyond the control of the actor and the audience.

(Chapter 4, “The Performative Creation of Materiality,” p. 262)

If I perceive the body of the performer as a special body and flesh in itself, for example, if I see the blood that sprinkled on the performer and the audience in Niche's rotten lamb performance in its characteristic red color, taste a strange sweetness in it, or feel the peculiar chewiness and writhing of the intestines under my feet, then I am perceiving all these phenomena as something in themselves.

The key here is not the general stimulus, but the perception of something in itself.

A thing means what it is, that is, what it appears phenomenally.

[… … ] In self-referentiality, materiality, signifier, and signified become one.

[… … ] To repeat, the subject who perceives the materiality of things accepts the meaning of that materiality.

In other words, it is to accept that phenomenal existence.

What an object perceived as something means is the perceived thing itself.

(Chapter 5, “The Emergence of Meaning,” p. 313)

Our culture is dominated by a fanatical obsession with youth, thinness, and toned muscles.

Any body that absolutely does not conform to this is branded as abnormal and restricted from the public world.

Disease and death are taboo or highly abhorrent in our society, and such bodies evoke disgust, nausea, disgust, and shame.

The Sochietas Raffaello Sanzio group usually put such bodies on stage without explaining in advance what was different from the norm required.

In doing so, the audience was exposed to the gaze on such bodies 'almost unprotected'.

The meanings that our society and most of its members attach to these bodies are no different from the emotions that are physically expressed and generated while perceiving them.

This feeling is undoubtedly cultural, with meaning given by each member of that culture.

These meanings define perception and evoke strong emotions.

(Chapter 5, “The Emergence of Meaning,” p. 337)

Performance artists create special situations in their performances where they surrender themselves to others.

When Beuys spent three days with a coyote, when Abramović exposed herself to the violence of others or was entangled with snakes, these artists voluntarily relinquished control and coordination of the performance process within the framework of what was possible.

Rather, they created situations that were difficult or nearly impossible to predict.

This development was not a matter for the artist alone, but always for someone else, most often the audience, or perhaps an animal.

What this means is that the artist places himself in a situation created not only by himself but also by others.

During the performance, the artist demanded that the audience, as observers, recognize the significance of the actions he had performed.

(Chapter 6, “Performance as an Event,” p. 363)

Artworks should not be misconstrued as political or moral statements.

Art cannot be blasphemous or pornographic, even if at first glance it seems to provoke subversion and revolution, glorify murder, rape, and theft, or slander God and show nudity.

Because a work of art means something very different.

Artworks are a complete disconnect from reality, where subversion and revolution occur, and where theft, blasphemy, and pornography are commonplace.

The autonomy of art presupposes a fundamental difference between art and reality, and art demands and asserts this difference.

Such claims about art have been fiercely contested in performance art and theatrical performances since the 1960s.

The argument that a work of art is not about showing and telling was not accepted.

(Chapter 6, “Performance as an Event,” p. 363)

The aesthetics of performance aims at art that transcends boundaries.

Historically, the aesthetics of performativity transcends boundaries that were established at the end of the 18th century and were considered fixed and insurmountable even afterward, boundaries that were so natural that they were considered laws of nature, and redefines the concept of boundaries.

If, up until now, building walls, separating, and principled distinctions have been considered important as perspectives that define art, the aesthetics of performativity reinforces the aspects of going beyond and transition.

Borders are not meant to separate us, but rather serve as thresholds that connect us.

In place of the unbridgeable conflicts, gradual differences take their place.

The aesthetics of performativity is not a project of disdifferentiation that unconditionally leads to the outbreak of violence, as Girard's theory of sacrifice suggests.

Rather, it is about overcoming rigid opposition and leading to dynamic differences.

If she had performed this act in any other public place, people would have had no hesitation in trying to stop her.

But what about this? If an artist is about to perform an act that seems deliberately planned, shouldn't we respect it? To interrupt it would be to risk damaging the "work" itself. But from a human perspective, is it acceptable to simply watch self-harm? Was the artist intending to invite the audience into the role of voyeur? Or was the artist experimenting with how long it would take for the audience to take action to end the performer's suffering? What is the right decision here? Through this performance, Abramović created a situation that forces the audience into a state of in-between art and everyday life, aesthetics and ethical norms.

(Chapter 1, “Why is the Aesthetics of Performance Necessary?”, p. 18)

For a performance to take place, the performers and the audience must gather at a specific place at a specific time and do something together.

Hermann defined it as “a play by everyone for everyone.”

Through this, he fundamentally redefined the relationship between actor and audience.

Until now, we have not thought of the audience as anything more than observers of the action taking place on stage.

[… … ] However, a performance is not a subject/object relationship in which the audience perceives the actor as an object of observation, nor is it a relationship in which the actor regards himself as a subject and the audience as an object, without exchanging meaning.

The physical co-presence of the actor and the audience is rather a relationship of co-subjectivity.

[… … ] In other words, a performance takes place between the performer and the audience and is co-created by them.

(Chapter 2, “Concept Explanation,” p. 63)

In "Dionysus 69" there is a scene that Schechner calls "the caressing god."

Here, the performers, the performance artists, go next to the audience, squat down or lie down, and begin to caress the audience.

They wore revealing clothing, especially bikini swimsuits for the women.

Audience reactions were varied.

Some audience members, especially the women, quietly and passively enjoyed the gentleness of the caresses.

Conversely, other audience members, mostly male, actively responded to this caressing, touching body parts that the performance artist had deliberately avoided.

The audience ignored the rules and regulations laid down by the artist in advance and accepted the situation as a real situation, not a 'play' about intimacy.

[… … ] What is clear here is that the actor intended to shake up and dismantle the dichotomous relationship between reality and fiction, publicness and intimacy, through contact, and in this way, to lead the audience into a familiar realm and provide them with a new experience.

However, the audience rather understood this act of contact dichotomously.

(Chapter 3, “Physical Co-Presence of Actor and Audience,” pp. 137–38)

Regardless of how or where they each moved, where they looked each time, whether they wore headphones or not, whether the actors' voices penetrated their ears through the headphones, or whether the voices gradually became inaudible as the chaotic voices and the noise of the shopping mall stores mixed together, it became impossible to distinguish between the actors in the theater and the passersby, and the busy movements of the shopping mall and the actors' actions continued to accumulate and overlap in new ways, creating a different spatiality each time.

This principle of creating spatiality was also applied in a significantly modified form of audio tour devised by the 'Hygiene Today' group.

(Chapter 4, “The Performative Creation of Materiality,” pp. 252–53)

The smell of food or drinks causes people to salivate when they breathe in and also affects the internal organs, resulting in strong appetite or disgust.

In this way, the audience who smells becomes aware of their own internal processes and realizes that they are a living organism.

Without a doubt, smell is the most powerful element in creating atmosphere.

This also relates to the fact that once a smell has spread, it can never be 'collected again'.

The resistance is also very strong.

Even when the smoke completely disappears, the smell remains and torments the audience.

Even when the charred eggs completely disappear from the stage, their smell still lingers in the space.

[… … ] The smell persists in attempting to fundamentally change the atmosphere, beyond the control of the actor and the audience.

(Chapter 4, “The Performative Creation of Materiality,” p. 262)

If I perceive the body of the performer as a special body and flesh in itself, for example, if I see the blood that sprinkled on the performer and the audience in Niche's rotten lamb performance in its characteristic red color, taste a strange sweetness in it, or feel the peculiar chewiness and writhing of the intestines under my feet, then I am perceiving all these phenomena as something in themselves.

The key here is not the general stimulus, but the perception of something in itself.

A thing means what it is, that is, what it appears phenomenally.

[… … ] In self-referentiality, materiality, signifier, and signified become one.

[… … ] To repeat, the subject who perceives the materiality of things accepts the meaning of that materiality.

In other words, it is to accept that phenomenal existence.

What an object perceived as something means is the perceived thing itself.

(Chapter 5, “The Emergence of Meaning,” p. 313)

Our culture is dominated by a fanatical obsession with youth, thinness, and toned muscles.

Any body that absolutely does not conform to this is branded as abnormal and restricted from the public world.

Disease and death are taboo or highly abhorrent in our society, and such bodies evoke disgust, nausea, disgust, and shame.

The Sochietas Raffaello Sanzio group usually put such bodies on stage without explaining in advance what was different from the norm required.

In doing so, the audience was exposed to the gaze on such bodies 'almost unprotected'.

The meanings that our society and most of its members attach to these bodies are no different from the emotions that are physically expressed and generated while perceiving them.

This feeling is undoubtedly cultural, with meaning given by each member of that culture.

These meanings define perception and evoke strong emotions.

(Chapter 5, “The Emergence of Meaning,” p. 337)

Performance artists create special situations in their performances where they surrender themselves to others.

When Beuys spent three days with a coyote, when Abramović exposed herself to the violence of others or was entangled with snakes, these artists voluntarily relinquished control and coordination of the performance process within the framework of what was possible.

Rather, they created situations that were difficult or nearly impossible to predict.

This development was not a matter for the artist alone, but always for someone else, most often the audience, or perhaps an animal.

What this means is that the artist places himself in a situation created not only by himself but also by others.

During the performance, the artist demanded that the audience, as observers, recognize the significance of the actions he had performed.

(Chapter 6, “Performance as an Event,” p. 363)

Artworks should not be misconstrued as political or moral statements.

Art cannot be blasphemous or pornographic, even if at first glance it seems to provoke subversion and revolution, glorify murder, rape, and theft, or slander God and show nudity.

Because a work of art means something very different.

Artworks are a complete disconnect from reality, where subversion and revolution occur, and where theft, blasphemy, and pornography are commonplace.

The autonomy of art presupposes a fundamental difference between art and reality, and art demands and asserts this difference.

Such claims about art have been fiercely contested in performance art and theatrical performances since the 1960s.

The argument that a work of art is not about showing and telling was not accepted.

(Chapter 6, “Performance as an Event,” p. 363)

The aesthetics of performance aims at art that transcends boundaries.

Historically, the aesthetics of performativity transcends boundaries that were established at the end of the 18th century and were considered fixed and insurmountable even afterward, boundaries that were so natural that they were considered laws of nature, and redefines the concept of boundaries.

If, up until now, building walls, separating, and principled distinctions have been considered important as perspectives that define art, the aesthetics of performativity reinforces the aspects of going beyond and transition.

Borders are not meant to separate us, but rather serve as thresholds that connect us.

In place of the unbridgeable conflicts, gradual differences take their place.

The aesthetics of performativity is not a project of disdifferentiation that unconditionally leads to the outbreak of violence, as Girard's theory of sacrifice suggests.

Rather, it is about overcoming rigid opposition and leading to dynamic differences.

---From the text

Publisher's Review

An artist who beats himself with a whip and cuts his stomach with a razor blade.

A pianist who sits at the piano and doesn't play a single note

Actors who hurled insults at the audience or harassed them while blindfolded… …

Breaking down the boundaries between audience and actor, body and mind, life and art

The performative shift in contemporary art and the advent of a new aesthetic

An interesting incident occurred during the performance of "Tomas's Lips" by performance artist Marina Abramović in 1975.

The artist sat naked, swallowed over a kilogram of honey and wine, then carved a star shape on his stomach with a razor blade and whipped his back before being dragged down by the audience to lie on an ice cross.

It was a kind of incident where the audience who was watching the artist perform an intended action intervened.

The dichotomous thinking that the artist is the subject who creates the work and the audience is the object who passively receives it can no longer be maintained.

In many performances, the audience does not just engage in conventional actions like clapping, but actually participates with as much rights as the actors.

Today, new genres of performing arts are proliferating, shaking up established values and norms and creating events that draw audiences in, and the relationship between audience and artist is also changing accordingly.

In this changing artistic environment, where the boundaries between art and life, aesthetics and ethics have collapsed and the distinctions between producers, recipients, and works of art have become unclear, contemporary art cannot be accurately explained solely through traditional aesthetic theories, and it even seems anachronistic.

In order to sensitively observe, study, and explain the performative shift in art from the concept of artwork to the concept of event since the 1960s, the emergence of a new aesthetic theory was inevitable.

And at the center of it all is this book, “The Aesthetics of Performance.”

A masterpiece by Erika Fischer-Lichte, a master of theatrical semiotics

"The Aesthetics of Performativity" is an essential book in theater studies and performance theory, and is the first Korean translation by Erika Fischer-Lichte, former director of the Institute for Theater Studies at the Free University of Berlin.

Performativity is a 'self-referential and reality-constituting act', and according to the author, the aesthetics of performativity focuses on the fact that the perceiving subject changes through a threshold experience with the object of perception.

In other words, the aesthetics of performance is based on the ‘transformative power that constitutes a new reality.’

The aesthetics of performativity encompasses not only artistic phenomena but also the power and reality-constructing power of non-artistic phenomena, and furthermore, aesthetic phenomena and experiences that transcend life and art, and provides a persuasive explanation for these.

The author analyzes contemporary theater, performance art, and cultural phenomena since the 1960s based on the theories of Durkheim, the founder of modern sociology, Vang Gennev's theory of rites of passage, and cultural anthropology that regards ritual as a transformative performance.

In particular, the aesthetic theory presented in this book is explained more easily by citing representative performances by Josef Beuys, Marina Abramović, Hermann Nitsch, Chris Burden, Max Reinhardt, and Richard Schechner as examples.

This book, "The Aesthetics of Performativity," outlines the development of art and aesthetic theory from the past to the present, and explores it across various cultural genres. By applying the analytical framework of new aesthetic theories such as corporeality, spatiality, sound, and temporality to actual performances, it presents a new way of reading that allows everyone from general audiences to professional critics to understand cultural performances more deeply and view them with open eyes.

The most excellent theoretical book for understanding the performing arts of the here and now.

The aesthetics of performance encompass all cultural performance genres, including various expressive arts such as theater, opera, dance, and performance art, as well as rituals, festivals, and sports competitions.

Essentially, these performance genres provide participants with an experience of being on the borderline, a threshold experience of being 'neither here nor there', and induce an experience of transformation.

The trends and flows related to this can be called a performative shift, which means that the conditions for producing and accepting art have changed decisively.

Now, the key is not the reproduction of a fictional world, but the establishment of a special relationship between the actor and the audience.

In other words, the key to the performance is not how the text was transferred to the stage or what means were used, but rather the 'event' that fundamentally redefines the relationship between actors and audience and opens up the possibility of a change in roles.

To explain this phenomenon, author Fischer-Lichte develops a theory centered on theatrical performances.

How do the actions of performers and audiences influence each other? Is performance an aesthetic or a social process? What is the relationship between the influence of the actor's body and the meaning of the work? How does materiality manifest performatively in performance, and what status does it hold? If the process and conclusion of a performance are not fixed but rather constantly changing, what circumstances and conditions do they depend on? This book sequentially poses these questions, leading readers step by step toward a theory of "the aesthetics of performativity."

The performative shift since the 1960s has not only accepted contingency as a condition and possibility of performance, but has also made it readily available.

Accordingly, today's directing strategies focus on auto-formative feedback loops, aiming for a change in roles between actors and audiences, community formation, and mutual contact.

The author explores the 'community formation' of performance through Schlepp's choral plays and Castorp's "Opportunity 2000", examines the role of 'contact' located between intimacy and publicness through Beuys's "Celtic+~~~", and examines the live nature of performance through Castorp's "The Idiot", which experiments with the audience's perceptual response in the face of the development of electronic media. Through these and other rich examples, the author develops a theory of the aesthetics of performativity in a more friendly and clear way.

Above all, the introduction of representative performances that have had a profound influence on the development of art, performances that feature diverse experiments and incredible imagination, makes this book even more interesting.

In conclusion, through this book, "The Aesthetics of Performativity," you will be able to get a quick overview of the development and evolution of modern art, look at aesthetic experience from a new perspective, and, above all, pay attention to the experience of "transformation" triggered by "performance."

In today's world, where the boundaries between art and life are more blurred than ever, this book is not only a must-read for professional critics, theorists, artists, and directors; it will also serve as a valuable resource for general readers, providing both insight and interest.

A pianist who sits at the piano and doesn't play a single note

Actors who hurled insults at the audience or harassed them while blindfolded… …

Breaking down the boundaries between audience and actor, body and mind, life and art

The performative shift in contemporary art and the advent of a new aesthetic

An interesting incident occurred during the performance of "Tomas's Lips" by performance artist Marina Abramović in 1975.

The artist sat naked, swallowed over a kilogram of honey and wine, then carved a star shape on his stomach with a razor blade and whipped his back before being dragged down by the audience to lie on an ice cross.

It was a kind of incident where the audience who was watching the artist perform an intended action intervened.

The dichotomous thinking that the artist is the subject who creates the work and the audience is the object who passively receives it can no longer be maintained.

In many performances, the audience does not just engage in conventional actions like clapping, but actually participates with as much rights as the actors.

Today, new genres of performing arts are proliferating, shaking up established values and norms and creating events that draw audiences in, and the relationship between audience and artist is also changing accordingly.

In this changing artistic environment, where the boundaries between art and life, aesthetics and ethics have collapsed and the distinctions between producers, recipients, and works of art have become unclear, contemporary art cannot be accurately explained solely through traditional aesthetic theories, and it even seems anachronistic.

In order to sensitively observe, study, and explain the performative shift in art from the concept of artwork to the concept of event since the 1960s, the emergence of a new aesthetic theory was inevitable.

And at the center of it all is this book, “The Aesthetics of Performance.”

A masterpiece by Erika Fischer-Lichte, a master of theatrical semiotics

"The Aesthetics of Performativity" is an essential book in theater studies and performance theory, and is the first Korean translation by Erika Fischer-Lichte, former director of the Institute for Theater Studies at the Free University of Berlin.

Performativity is a 'self-referential and reality-constituting act', and according to the author, the aesthetics of performativity focuses on the fact that the perceiving subject changes through a threshold experience with the object of perception.

In other words, the aesthetics of performance is based on the ‘transformative power that constitutes a new reality.’

The aesthetics of performativity encompasses not only artistic phenomena but also the power and reality-constructing power of non-artistic phenomena, and furthermore, aesthetic phenomena and experiences that transcend life and art, and provides a persuasive explanation for these.

The author analyzes contemporary theater, performance art, and cultural phenomena since the 1960s based on the theories of Durkheim, the founder of modern sociology, Vang Gennev's theory of rites of passage, and cultural anthropology that regards ritual as a transformative performance.

In particular, the aesthetic theory presented in this book is explained more easily by citing representative performances by Josef Beuys, Marina Abramović, Hermann Nitsch, Chris Burden, Max Reinhardt, and Richard Schechner as examples.

This book, "The Aesthetics of Performativity," outlines the development of art and aesthetic theory from the past to the present, and explores it across various cultural genres. By applying the analytical framework of new aesthetic theories such as corporeality, spatiality, sound, and temporality to actual performances, it presents a new way of reading that allows everyone from general audiences to professional critics to understand cultural performances more deeply and view them with open eyes.

The most excellent theoretical book for understanding the performing arts of the here and now.

The aesthetics of performance encompass all cultural performance genres, including various expressive arts such as theater, opera, dance, and performance art, as well as rituals, festivals, and sports competitions.

Essentially, these performance genres provide participants with an experience of being on the borderline, a threshold experience of being 'neither here nor there', and induce an experience of transformation.

The trends and flows related to this can be called a performative shift, which means that the conditions for producing and accepting art have changed decisively.

Now, the key is not the reproduction of a fictional world, but the establishment of a special relationship between the actor and the audience.

In other words, the key to the performance is not how the text was transferred to the stage or what means were used, but rather the 'event' that fundamentally redefines the relationship between actors and audience and opens up the possibility of a change in roles.

To explain this phenomenon, author Fischer-Lichte develops a theory centered on theatrical performances.

How do the actions of performers and audiences influence each other? Is performance an aesthetic or a social process? What is the relationship between the influence of the actor's body and the meaning of the work? How does materiality manifest performatively in performance, and what status does it hold? If the process and conclusion of a performance are not fixed but rather constantly changing, what circumstances and conditions do they depend on? This book sequentially poses these questions, leading readers step by step toward a theory of "the aesthetics of performativity."

The performative shift since the 1960s has not only accepted contingency as a condition and possibility of performance, but has also made it readily available.

Accordingly, today's directing strategies focus on auto-formative feedback loops, aiming for a change in roles between actors and audiences, community formation, and mutual contact.

The author explores the 'community formation' of performance through Schlepp's choral plays and Castorp's "Opportunity 2000", examines the role of 'contact' located between intimacy and publicness through Beuys's "Celtic+~~~", and examines the live nature of performance through Castorp's "The Idiot", which experiments with the audience's perceptual response in the face of the development of electronic media. Through these and other rich examples, the author develops a theory of the aesthetics of performativity in a more friendly and clear way.

Above all, the introduction of representative performances that have had a profound influence on the development of art, performances that feature diverse experiments and incredible imagination, makes this book even more interesting.

In conclusion, through this book, "The Aesthetics of Performativity," you will be able to get a quick overview of the development and evolution of modern art, look at aesthetic experience from a new perspective, and, above all, pay attention to the experience of "transformation" triggered by "performance."

In today's world, where the boundaries between art and life are more blurred than ever, this book is not only a must-read for professional critics, theorists, artists, and directors; it will also serve as a valuable resource for general readers, providing both insight and interest.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: August 22, 2017

- Page count, weight, size: 502 pages | 718g | 153*226*26mm

- ISBN13: 9788932029870

- ISBN10: 8932029873

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)