Archive Taste

|

Description

Book Introduction

About writing history from archives

A French historian's intense reflections and reflections

Retrieving the lives of the common people from a pile of 18th-century documents!

In March 2020, some interesting news was reported.

Following Pope Francis' decision, the archive of secret documents from the time of Pope Pius XII has been opened.

The archives contain approximately 2 million documents, and the length of the shelves containing the records is said to be approximately 85 kilometers.

This opening has garnered much attention and anticipation from the academic community, as it will allow them to confirm the Vatican's position and role regarding the Holocaust during World War II.

What would it be like to unearth fragments of ancient records, raw and dormant, not "written history" through someone else's interpretation, but rather to touch, see, read, copy, and interpret these documents, bringing the past to life? It feels as if profound secrets lie dormant within, opening up new horizons previously unknown.

The archives contain the voices of ordinary citizens whose stories are not recorded in history books.

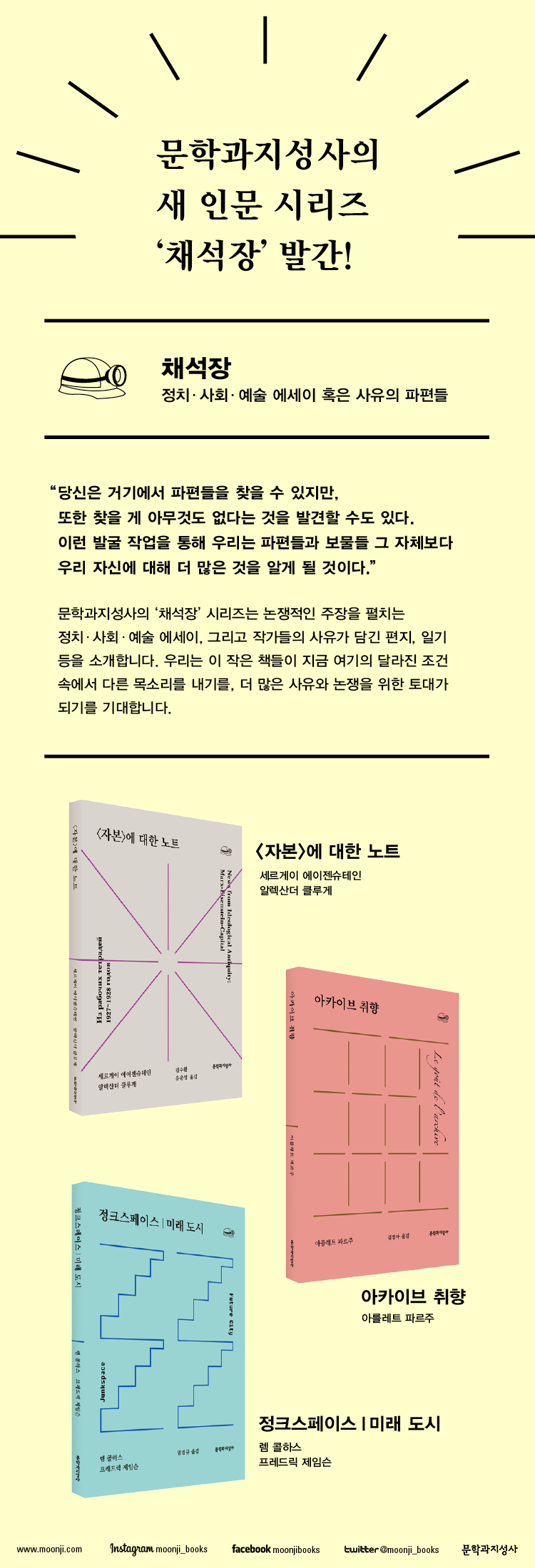

A book titled "Archive Taste" has been published, which presents a profound philosophy on writing history through archives.

This book is an essay that follows the journey of a historical researcher as he carries out archival work, condensing the concerns, reflections, and questions that arise along the way in a beautifully written style.

Arlette Farge, a historian who Robert Darnton called “one of France’s greatest historians,” has studied the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment and participated in major European historical projects such as “A History of Western Women,” and has shown a deep interest in marginalized groups such as the masses, the poor, and women.

In this book, she shares her insights gained from researching 18th-century criminal case archives, her philosophy of history, and suggestions for historical researchers.

A French historian's intense reflections and reflections

Retrieving the lives of the common people from a pile of 18th-century documents!

In March 2020, some interesting news was reported.

Following Pope Francis' decision, the archive of secret documents from the time of Pope Pius XII has been opened.

The archives contain approximately 2 million documents, and the length of the shelves containing the records is said to be approximately 85 kilometers.

This opening has garnered much attention and anticipation from the academic community, as it will allow them to confirm the Vatican's position and role regarding the Holocaust during World War II.

What would it be like to unearth fragments of ancient records, raw and dormant, not "written history" through someone else's interpretation, but rather to touch, see, read, copy, and interpret these documents, bringing the past to life? It feels as if profound secrets lie dormant within, opening up new horizons previously unknown.

The archives contain the voices of ordinary citizens whose stories are not recorded in history books.

A book titled "Archive Taste" has been published, which presents a profound philosophy on writing history through archives.

This book is an essay that follows the journey of a historical researcher as he carries out archival work, condensing the concerns, reflections, and questions that arise along the way in a beautifully written style.

Arlette Farge, a historian who Robert Darnton called “one of France’s greatest historians,” has studied the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment and participated in major European historical projects such as “A History of Western Women,” and has shown a deep interest in marginalized groups such as the masses, the poor, and women.

In this book, she shares her insights gained from researching 18th-century criminal case archives, her philosophy of history, and suggestions for historical researchers.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Countless traces

There is a notice posted on the entrance door indicating the operating hours.

Who's in the archives

When I arrived at the manuscript reading room, they asked me to show them my pass.

Collection stage

stranded sentences

The reading room of the manuscript catalog is like a giant tomb.

The history of the beach

Translator's Note

There is a notice posted on the entrance door indicating the operating hours.

Who's in the archives

When I arrived at the manuscript reading room, they asked me to show them my pass.

Collection stage

stranded sentences

The reading room of the manuscript catalog is like a giant tomb.

The history of the beach

Translator's Note

Detailed image

Into the book

The interrogation and statement materials in the criminal case archives seem to work miracles, connecting the past to the present.

The work here no longer seems to be about dead beings, and the material here seems to be so sharp that it stimulates both the intellect and the emotions.

[… … ] Whether they were witnesses, neighbors, thieves, conmen, or rioters, their words, actions, and thoughts were recorded not because they wanted to, but for entirely different reasons.

So everything changes.

Not only the content of the text changes, but also the relationship between the writer and the text changes.

In particular, the sense of reality felt by workers changes.

It seems that reality clings more tenaciously.

You could say that reality is creeping in.

---From "Countless Traces"

The archives of 18th-century criminal cases are filled with more characters than any other book or novel.

The bustling crowd of characters whose names you know but whose personalities you have no idea about actually causes the worker to feel even more lonely.

This is the shocking contradiction that the archive presents to its workers early on.

[… … ] As the ‘living’ beings overwhelmingly invade us, it seems impossible to recognize them all and write them down in history.

Countless traces… It’s every worker’s dream.

In front of the countless traces, the worker hesitates on the one hand, but on the other hand, he is fascinated and approaches them.

---From "Countless Traces"

Politics in the formal sense may not seem like a women's arena, but surprisingly, the women in the 18th-century archives never left politics.

In all the popular uprisings, big and small, women were not only present but also actively participated in the struggle.

They incited uprisings against men and even confronted police and soldiers with clubs and sticks.

The men were not at all surprised.

In some cases, women were encouraged to lead the way or shout from high windows.

---From "Who's in the Archives"

It cannot be overstated how slow archival work is, and how creative the slow movements of hands and heads can be in the archive.

Being creative because it's slow is something that can only be said later, and getting faster in the first place is an impossible task.

The task of reading through the data one by one seems never-ending.

Even if the amount of data is limited as much as possible through a pre-determined sampling method and precise calculations, it still requires tremendous patience to read it all.

---From the "Collection Stage"

A lifetime would not be enough to read the entire archive of 18th-century criminal cases, but the desire to read through the archive in a disorderly and aimless manner, to feel the wonder, to simply savor the archive, to feel the overflow of life in the strings of ordinary sentences, is not weakened by the lack of time, but rather strengthened.

As you freely collect details about countless unknown people who disappeared long ago, you may find yourself enjoying it enough to forget that writing history requires a different kind of intellectual effort.

---From the "Collection Stage"

The worker must forge a path through the archive's sparseness, and create questions from its groping answers and unspoken words.

The kaleidoscope keeps changing its shape before your eyes.

The image that appears before our eyes for a moment disappears before it can solidify into a clear hypothesis.

A brilliantly shining image instantly becomes another image and shines differently.

A very small shake is enough to cause a different image to appear.

The meaning of the archive is dynamic and fleeting, like a kaleidoscope of images.

---From "Stranded Sentences"

The preference for small fragments of words and actions also influences the rhythm and language of writing.

Writings that rely on small fragments within the archive find rhythm in probable rather than inevitable plots, and they seek a language that can offer new and unexpected knowledge while simultaneously not concealing their own ignorance.

To write history not of what actually happened but of what could have happened, to write a history in which the capricious and chaotic order that creates everyday life is revealed naturally through the plot lines of events, is a risky endeavor that simultaneously gains and loses plausibility.

The work here no longer seems to be about dead beings, and the material here seems to be so sharp that it stimulates both the intellect and the emotions.

[… … ] Whether they were witnesses, neighbors, thieves, conmen, or rioters, their words, actions, and thoughts were recorded not because they wanted to, but for entirely different reasons.

So everything changes.

Not only the content of the text changes, but also the relationship between the writer and the text changes.

In particular, the sense of reality felt by workers changes.

It seems that reality clings more tenaciously.

You could say that reality is creeping in.

---From "Countless Traces"

The archives of 18th-century criminal cases are filled with more characters than any other book or novel.

The bustling crowd of characters whose names you know but whose personalities you have no idea about actually causes the worker to feel even more lonely.

This is the shocking contradiction that the archive presents to its workers early on.

[… … ] As the ‘living’ beings overwhelmingly invade us, it seems impossible to recognize them all and write them down in history.

Countless traces… It’s every worker’s dream.

In front of the countless traces, the worker hesitates on the one hand, but on the other hand, he is fascinated and approaches them.

---From "Countless Traces"

Politics in the formal sense may not seem like a women's arena, but surprisingly, the women in the 18th-century archives never left politics.

In all the popular uprisings, big and small, women were not only present but also actively participated in the struggle.

They incited uprisings against men and even confronted police and soldiers with clubs and sticks.

The men were not at all surprised.

In some cases, women were encouraged to lead the way or shout from high windows.

---From "Who's in the Archives"

It cannot be overstated how slow archival work is, and how creative the slow movements of hands and heads can be in the archive.

Being creative because it's slow is something that can only be said later, and getting faster in the first place is an impossible task.

The task of reading through the data one by one seems never-ending.

Even if the amount of data is limited as much as possible through a pre-determined sampling method and precise calculations, it still requires tremendous patience to read it all.

---From the "Collection Stage"

A lifetime would not be enough to read the entire archive of 18th-century criminal cases, but the desire to read through the archive in a disorderly and aimless manner, to feel the wonder, to simply savor the archive, to feel the overflow of life in the strings of ordinary sentences, is not weakened by the lack of time, but rather strengthened.

As you freely collect details about countless unknown people who disappeared long ago, you may find yourself enjoying it enough to forget that writing history requires a different kind of intellectual effort.

---From the "Collection Stage"

The worker must forge a path through the archive's sparseness, and create questions from its groping answers and unspoken words.

The kaleidoscope keeps changing its shape before your eyes.

The image that appears before our eyes for a moment disappears before it can solidify into a clear hypothesis.

A brilliantly shining image instantly becomes another image and shines differently.

A very small shake is enough to cause a different image to appear.

The meaning of the archive is dynamic and fleeting, like a kaleidoscope of images.

---From "Stranded Sentences"

The preference for small fragments of words and actions also influences the rhythm and language of writing.

Writings that rely on small fragments within the archive find rhythm in probable rather than inevitable plots, and they seek a language that can offer new and unexpected knowledge while simultaneously not concealing their own ignorance.

To write history not of what actually happened but of what could have happened, to write a history in which the capricious and chaotic order that creates everyday life is revealed naturally through the plot lines of events, is a risky endeavor that simultaneously gains and loses plausibility.

---From "History of the Beach"

Publisher's Review

The hands of an archivist who breathes life into the anonymous people of the past.

How does something become history?

Considered one of the most beautiful libraries in Paris, France, the Arsenal Library houses a large collection of documents related to various criminal cases from the 18th century.

Also known as the Bastille Archive.

It was initially stored in a damp underground vault and was only classified as valuable after it was damaged by seeping rain.

Here, interrogation records and trial records of prisoners imprisoned in the Bastille, various indictments, and illegal posters torn from the walls by the 18th-century police are jumbled together.

The archive is not a place where history is written, but where the trivial and the profound unfold in equal measure.

And what researchers who prefer archives focus on are the ordinary lives of ordinary characters.

The 18th-century Bastille Archive, the subject of study in this book, is filled with a wealth of stories that would have remained unrecorded had the people of the time not been exposed to the public authorities.

Street life, rumors, various brawls, the actions and opinions of ordinary people—these seemingly trivial incidents lie in the archives, waiting to be unearthed like raw gems.

But for these to see the light of day, they require the collection and selection of historians who seek to transform what they contain into questions and approach the truth.

A striking example of this is revealed in the section that focuses on the specific and dynamic lives of women of the time.

Since the 1980s, as history has focused on the private sphere, the presence of women, previously overlooked, has begun to be revealed. However, in many cases, this has been limited to adding appendices to existing historical knowledge.

However, if we look into the archives, we can find women who are living, moving, three-dimensional figures that go beyond ‘genre paintings.’

Archivists can examine the conditions of women, the social and political environment in which they were treated at the time, and perceive how women participated in a male-dominated world and how they fulfilled full social roles.

It is a work of making women visible in places where women were invisible, where history did not try to see women.

Archival materials not only allow us to see the lives of the people as they are by breaking down pre-existing images, but also allow us to reflect deeply on the fact that existing history is written from the perspective of the victors.

How do historians with an "archival taste" work?

“Archive taste” refers to a unique attitude of digging through piles of data on unknown people forgotten by history, bringing the things buried therein into the arena of historical discussion, and discussing and reflecting on them.

As the worker reads the language of the archive and listens to the lives of the lowly, he or she is able to hear sounds that were previously unheard.

Archival taste is formed through encounters with fascinating shadows that have rarely been illuminated, encounters with beings who are both hostile and hostile, and encounters with people damaged by the violence of their time.

So how does a historian with an archival bent work? Drawing on his own experience, the author recounts the process of historical research, which involves being glued to a library, constantly reading, copying, categorizing, and deciphering materials until his shoulders and neck become stiff.

The author also discusses the rules for historians working with archives.

Historians must always be careful not to make archives an object of desire, abandon the idea that they can understand something by reading it once, be wary of the danger of homogenization that causes them to lose their distance from the source material or the danger of becoming dry footnotes by repeating the material, avoid adding fiction like historical novels to breathe life into archives, abandon the perspective that universalizes the subject of research and write articles that craft the situation at the time as precisely as possible, and avoid adding their own thoughts to the archive while constantly seeking the meaning of the event.

This book, which provides a close look into the work of historians who rely on archives, offers many lessons and food for thought for historical researchers and related specialists.

Furthermore, for general readers who have only seen history books as finished products, this book will satisfy their intellectual curiosity by allowing them to observe the intense research process of a historian, something they rarely encounter, and will allow them to reflect on the true attitude toward learning and research, making for an enjoyable reading experience.

“The reason why we must write history is

Not to talk about the dead past

“To participate in a conversation between living beings.”

This book has an interesting structure.

Beginning with a story about the rough texture and vastness of the archives, covered in white dust, the book contains five essays that sequentially illuminate the archival work process.

Also interspersed among the essays are humorous short stories depicting researchers working in a library, such as competing for a good seat, being sensitive to even the slightest noise, and wondering what other people are looking at and why.

"Countless Traces" sensually depicts the experience of browsing an archive, exploring the allure of archives and how workers are captivated by their allure.

The book compares printed and manuscript materials, autobiographical records, and various statements from the archives, and explains the archival work process with abundant examples such as trump cards, quill pen marks, cloth letters, and seed envelopes discovered among the archive documents.

"Who's in the Archives" tells the story of what was discovered, what was experienced, and what was insightful as one reads through the police records of 18th-century Paris.

What is 'truth' and what is 'reality' in the statements the public makes against those in power?

How can we write the history of the "masses" and the history of "women"? This book concisely captures profound reflections and questions born from experience.

"The Collection Stage" starkly illustrates, through its description of a monotonous and lengthy process, how even the most radical visions inevitably begin with turning each page of old paper.

It also provides a brief overview of the qualities and capabilities required of a history researcher.

"Stranded Sentences" describes the vast abyss between complex lives and criminal case data, the vast chasm between individual stories and so-called historical facts.

In particular, the author's fierce criticism of historical revisionism resonates deeply with readers.

Finally, "The Historian of the Beach" concludes with the author's cautious opinion on why history should be written.

How does something become history?

Considered one of the most beautiful libraries in Paris, France, the Arsenal Library houses a large collection of documents related to various criminal cases from the 18th century.

Also known as the Bastille Archive.

It was initially stored in a damp underground vault and was only classified as valuable after it was damaged by seeping rain.

Here, interrogation records and trial records of prisoners imprisoned in the Bastille, various indictments, and illegal posters torn from the walls by the 18th-century police are jumbled together.

The archive is not a place where history is written, but where the trivial and the profound unfold in equal measure.

And what researchers who prefer archives focus on are the ordinary lives of ordinary characters.

The 18th-century Bastille Archive, the subject of study in this book, is filled with a wealth of stories that would have remained unrecorded had the people of the time not been exposed to the public authorities.

Street life, rumors, various brawls, the actions and opinions of ordinary people—these seemingly trivial incidents lie in the archives, waiting to be unearthed like raw gems.

But for these to see the light of day, they require the collection and selection of historians who seek to transform what they contain into questions and approach the truth.

A striking example of this is revealed in the section that focuses on the specific and dynamic lives of women of the time.

Since the 1980s, as history has focused on the private sphere, the presence of women, previously overlooked, has begun to be revealed. However, in many cases, this has been limited to adding appendices to existing historical knowledge.

However, if we look into the archives, we can find women who are living, moving, three-dimensional figures that go beyond ‘genre paintings.’

Archivists can examine the conditions of women, the social and political environment in which they were treated at the time, and perceive how women participated in a male-dominated world and how they fulfilled full social roles.

It is a work of making women visible in places where women were invisible, where history did not try to see women.

Archival materials not only allow us to see the lives of the people as they are by breaking down pre-existing images, but also allow us to reflect deeply on the fact that existing history is written from the perspective of the victors.

How do historians with an "archival taste" work?

“Archive taste” refers to a unique attitude of digging through piles of data on unknown people forgotten by history, bringing the things buried therein into the arena of historical discussion, and discussing and reflecting on them.

As the worker reads the language of the archive and listens to the lives of the lowly, he or she is able to hear sounds that were previously unheard.

Archival taste is formed through encounters with fascinating shadows that have rarely been illuminated, encounters with beings who are both hostile and hostile, and encounters with people damaged by the violence of their time.

So how does a historian with an archival bent work? Drawing on his own experience, the author recounts the process of historical research, which involves being glued to a library, constantly reading, copying, categorizing, and deciphering materials until his shoulders and neck become stiff.

The author also discusses the rules for historians working with archives.

Historians must always be careful not to make archives an object of desire, abandon the idea that they can understand something by reading it once, be wary of the danger of homogenization that causes them to lose their distance from the source material or the danger of becoming dry footnotes by repeating the material, avoid adding fiction like historical novels to breathe life into archives, abandon the perspective that universalizes the subject of research and write articles that craft the situation at the time as precisely as possible, and avoid adding their own thoughts to the archive while constantly seeking the meaning of the event.

This book, which provides a close look into the work of historians who rely on archives, offers many lessons and food for thought for historical researchers and related specialists.

Furthermore, for general readers who have only seen history books as finished products, this book will satisfy their intellectual curiosity by allowing them to observe the intense research process of a historian, something they rarely encounter, and will allow them to reflect on the true attitude toward learning and research, making for an enjoyable reading experience.

“The reason why we must write history is

Not to talk about the dead past

“To participate in a conversation between living beings.”

This book has an interesting structure.

Beginning with a story about the rough texture and vastness of the archives, covered in white dust, the book contains five essays that sequentially illuminate the archival work process.

Also interspersed among the essays are humorous short stories depicting researchers working in a library, such as competing for a good seat, being sensitive to even the slightest noise, and wondering what other people are looking at and why.

"Countless Traces" sensually depicts the experience of browsing an archive, exploring the allure of archives and how workers are captivated by their allure.

The book compares printed and manuscript materials, autobiographical records, and various statements from the archives, and explains the archival work process with abundant examples such as trump cards, quill pen marks, cloth letters, and seed envelopes discovered among the archive documents.

"Who's in the Archives" tells the story of what was discovered, what was experienced, and what was insightful as one reads through the police records of 18th-century Paris.

What is 'truth' and what is 'reality' in the statements the public makes against those in power?

How can we write the history of the "masses" and the history of "women"? This book concisely captures profound reflections and questions born from experience.

"The Collection Stage" starkly illustrates, through its description of a monotonous and lengthy process, how even the most radical visions inevitably begin with turning each page of old paper.

It also provides a brief overview of the qualities and capabilities required of a history researcher.

"Stranded Sentences" describes the vast abyss between complex lives and criminal case data, the vast chasm between individual stories and so-called historical facts.

In particular, the author's fierce criticism of historical revisionism resonates deeply with readers.

Finally, "The Historian of the Beach" concludes with the author's cautious opinion on why history should be written.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: March 10, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 168 pages | 182g | 128*187*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788932036045

- ISBN10: 8932036047

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)