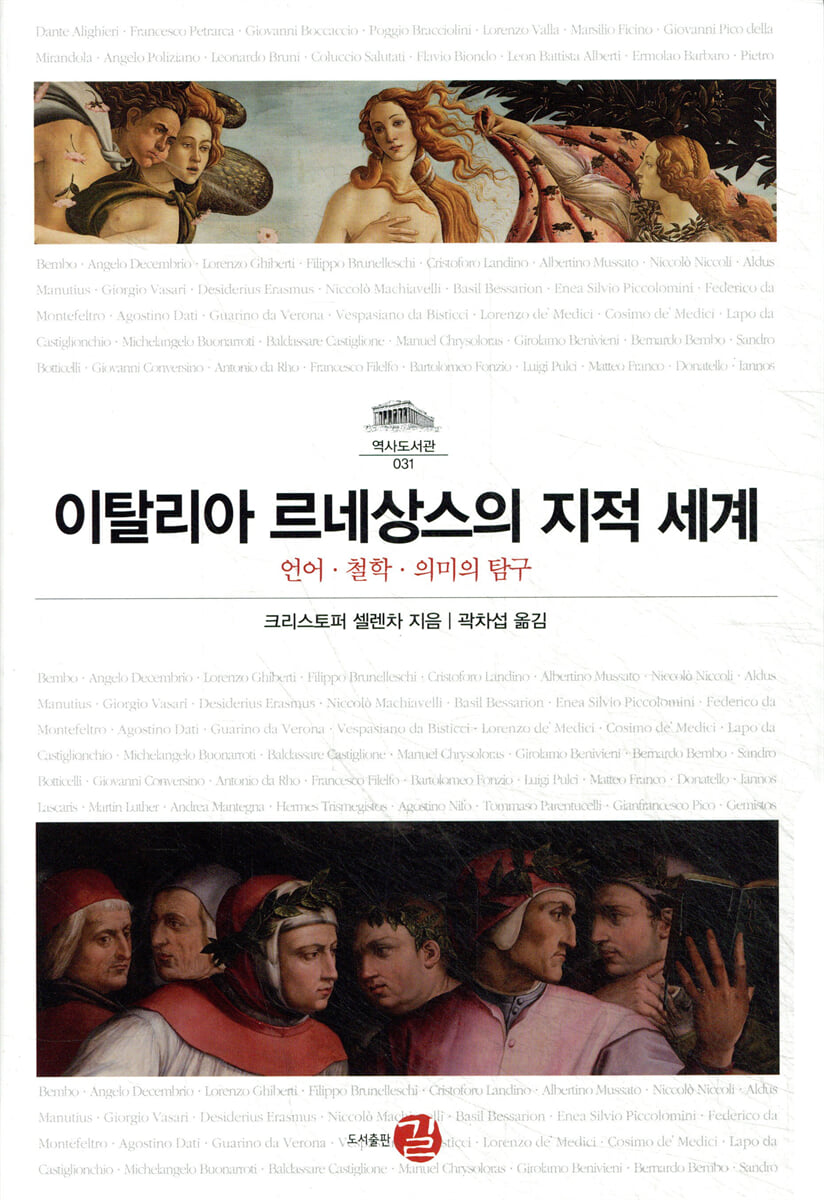

The intellectual world of the Italian Renaissance

|

Description

Book Introduction

The Renaissance was an important period not only in art but also in intellectual and philosophical history!

When general readers think of the Renaissance, most of what comes to mind is the Renaissance as ‘art’ and ‘architecture.’

However, even during the Renaissance, philosophy and thought were discussed in abundance, and the horizons of high-level thought were broadened through various writings.

For approximately 200 years, from the 14th century to the mid-16th century, in the heart of the Renaissance, Italy (especially Florence), the intellectual trend was led by 'humanism', which actively interacted with various philosophical schools that had existed until the previous period, such as Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism, skepticism, and Epicureanism, and sometimes accepted them and sometimes rejected them, showing an eclectic attitude.

Naturally, such aspects raised the academic question of how the Italian Renaissance could be defined.

Was it an extension of the Middle Ages or the beginning of the modern era? Was it philosophical or literary? Did it seek to awaken a new human spirit and present a new perspective on humanity, or did it simply restore and elevate the writings of classical antiquity? For the past hundred years or so, Western academia has been embroiled in countless debates and controversies surrounding the nature and meaning of Renaissance humanism.

This book is a translation of the controversial work of Renaissance scholar Christopher Selenza, which presents the latest research findings in a debate that has lasted for a century.

Naturally, through the translation of this book, our readers will gain another insight into the Renaissance. This is because the Renaissance, which has been understood primarily as a period centered on the world of art, including painting and architecture, was also a very significant period in terms of intellectual and philosophical history.

When general readers think of the Renaissance, most of what comes to mind is the Renaissance as ‘art’ and ‘architecture.’

However, even during the Renaissance, philosophy and thought were discussed in abundance, and the horizons of high-level thought were broadened through various writings.

For approximately 200 years, from the 14th century to the mid-16th century, in the heart of the Renaissance, Italy (especially Florence), the intellectual trend was led by 'humanism', which actively interacted with various philosophical schools that had existed until the previous period, such as Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism, skepticism, and Epicureanism, and sometimes accepted them and sometimes rejected them, showing an eclectic attitude.

Naturally, such aspects raised the academic question of how the Italian Renaissance could be defined.

Was it an extension of the Middle Ages or the beginning of the modern era? Was it philosophical or literary? Did it seek to awaken a new human spirit and present a new perspective on humanity, or did it simply restore and elevate the writings of classical antiquity? For the past hundred years or so, Western academia has been embroiled in countless debates and controversies surrounding the nature and meaning of Renaissance humanism.

This book is a translation of the controversial work of Renaissance scholar Christopher Selenza, which presents the latest research findings in a debate that has lasted for a century.

Naturally, through the translation of this book, our readers will gain another insight into the Renaissance. This is because the Renaissance, which has been understood primarily as a period centered on the world of art, including painting and architecture, was also a very significant period in terms of intellectual and philosophical history.

index

Translator's Preface 7

Introduction 31

Acknowledgements 37

List of abbreviations 39

1.

Start 43

2.

Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio 67

3.

The Italian Renaissance Takes Root in Florence 109

4.

Florentine Humanism, Translation, New (Old) Philosophy 149

5.

Dialogue, Institutions, and Social Exchange 183

6.

Who Owns Culture? Classicism, Institutions, and Slang 221

7.

Pozzo Braciolini 247

8.

Lorenzo Valla 275

9.

The Nature of Latin: Pozzo vs. Bala 307

10.

Balla, Latin, Christianity, Culture 339

11.

Changing Environment 381

12.

Florence: Marsilio Ficino 1401

13.

Picino 2 435

14.

Voices of Florentine Culture in the Late Fifteenth Century 469

15.

"I can hardly breathe": Poliziano, Pico, Ficino, and the beginning of the end of the Florentine Renaissance 505

16.

Angelo Poliziano's Lamia in Context 541

17.

Endings and New Beginnings: The Language Debate 593

Epilogue 635

Reference 641

Search 681

Introduction 31

Acknowledgements 37

List of abbreviations 39

1.

Start 43

2.

Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio 67

3.

The Italian Renaissance Takes Root in Florence 109

4.

Florentine Humanism, Translation, New (Old) Philosophy 149

5.

Dialogue, Institutions, and Social Exchange 183

6.

Who Owns Culture? Classicism, Institutions, and Slang 221

7.

Pozzo Braciolini 247

8.

Lorenzo Valla 275

9.

The Nature of Latin: Pozzo vs. Bala 307

10.

Balla, Latin, Christianity, Culture 339

11.

Changing Environment 381

12.

Florence: Marsilio Ficino 1401

13.

Picino 2 435

14.

Voices of Florentine Culture in the Late Fifteenth Century 469

15.

"I can hardly breathe": Poliziano, Pico, Ficino, and the beginning of the end of the Florentine Renaissance 505

16.

Angelo Poliziano's Lamia in Context 541

17.

Endings and New Beginnings: The Language Debate 593

Epilogue 635

Reference 641

Search 681

Publisher's Review

Baron, Garin, and Christeller's discourse debate on defining the character of the Italian Renaissance

In Western academia, the discourse on defining the nature of the Renaissance has been led by Hans Baron (1900-1988), Eugenio Garin (1909-2004), and Paul Oskar Kristeller (1905-1999).

Among these, Baron's discussion of humanism was inextricably linked to 'republican freedom', and he viewed the war of 1402 between the Republic of Florence and the Tyrant of Milan as a crucial period in Western civilization from the perspective of the confrontation and conflict between 'freedom' and 'tyranny'.

In his view, the Florentine humanist writers were able to effectively combine political rhetoric and action by actively defending republican liberty against the absolutism of the Visconti tyrants of Milan.

It is said that a modern consciousness called 'civic humanism' emerged to replace the static classicism of the 14th century humanists.

This is the 'vita activa' or 'vivere civile', which states that citizens have the right and duty to actively participate in the governance of the country.

Eugenio Garin also sought to find a manifestation of modernity in Renaissance humanism, but unlike Baron, who focused on the relationship between historical events and ideologies, he viewed humanism as an important turning point in the history of Western philosophy, that is, as a transition to modernity.

In his view, the Italian Renaissance was essentially a movement to elevate and transform the culture and values of ancient peoples within the historical environment of Renaissance Italy.

In particular, the achievements of Renaissance humanists were philology, which they called 'grammatica' - philology at that time was not philology in the narrow sense of the modern day, but rather 'philosophy' in the broad sense of presenting a new perspective on humans and the world.

Naturally, it was based on a dislike for scholastic philosophy, which was mired in metaphysics and theology, and turned towards concrete studies - through which he saw the practice of a new kind of philosophy, or philosophy - in a broad sense - which was a new transformation of the ancient concept of 'philosophy' - the love of wisdom.

In short, Garin argued for ‘very practical philosophizing’ (proprio effettivo filosofare) or ‘philology as philosophy.’

Christeller is the scholar who stands in opposition to Garin, who regards Renaissance humanism as a new 'philosophy' that rebelled against scholastic philosophy (or traditional philosophy).

On almost every point of history and philosophy, Garin and Christeller are polar opposites.

For Christeller, Renaissance humanists were heirs to medieval rhetoricians, and so they believed that the best way to achieve eloquence was to imitate the style of classical works such as Cicero.

That is, most of these humanists were 'professional rhetoricians' who studied the classics and explored classical linguistics, either as clerks in monarchies or republics or as teachers of grammar and rhetoric in universities or lower schools.

Therefore, in his view, Renaissance humanism is “a cultural and educational program that emphasizes and develops the humanities rather than a philosophical tendency or system,” and humanists are “not philosophers at all.”

The author of this book re-establishes Renaissance humanism based on philosophy as a way of life.

Currently, the study of Renaissance humanism is showing a trend in which the 'philosophical school' following Christeller is attacking the solid fortress of the 'rhetorical school' while the 'civic values' emphasized by Baron still form one axis.

The 'philosophical school' is roughly divided into two branches (though the two are closely related): one is that which seeks to 'philosophize' or 'philosophy as philosophy' in a humanistic way, and the other is that humanist philosophy aims for 'philosophy as a way of life' rather than the dialectics of traditional scholastic philosophy.

According to Pierre Hadot, the French philosopher who advocated 'philosophy as a way of life', it is "a way of being-in-the-world that must be practiced at every moment with the goal of transforming one's entire life."

Philosophy was originally conceived as the love of wisdom, and wisdom “does not merely enable us to know, but makes us ‘be’ in a different way.” The author of this book, Selenza, follows Addo’s model of philosophy and argues that during the Renaissance, the word ‘philosopher’ was used in a broad sense, and that the philosophy that humanists conceived of was the search for wisdom in all areas of life.

This idea has persisted since ancient times, and from the end of the 18th century, a theoretical and dialectical philosophy became mainstream.

Thus, Petrarch, while criticizing Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, said that the essence of philosophy is 'care for the soul' (Alberti followed suit), Leonardo Bruni intentionally omitted Aristotle's metaphysics to make him a humanist, and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola considered attitude toward life to be one aspect of a true philosopher.

They all pursued a Socratic view on how to live.

With these points in mind, the author emphasizes that philosophy is not simply about pursuing knowledge, but about transforming oneself through that knowledge; that is, it is not about clinging to logical consistency and commentary alone, and that the meaning of Renaissance humanism must be sought in that respect.

In Western academia, the discourse on defining the nature of the Renaissance has been led by Hans Baron (1900-1988), Eugenio Garin (1909-2004), and Paul Oskar Kristeller (1905-1999).

Among these, Baron's discussion of humanism was inextricably linked to 'republican freedom', and he viewed the war of 1402 between the Republic of Florence and the Tyrant of Milan as a crucial period in Western civilization from the perspective of the confrontation and conflict between 'freedom' and 'tyranny'.

In his view, the Florentine humanist writers were able to effectively combine political rhetoric and action by actively defending republican liberty against the absolutism of the Visconti tyrants of Milan.

It is said that a modern consciousness called 'civic humanism' emerged to replace the static classicism of the 14th century humanists.

This is the 'vita activa' or 'vivere civile', which states that citizens have the right and duty to actively participate in the governance of the country.

Eugenio Garin also sought to find a manifestation of modernity in Renaissance humanism, but unlike Baron, who focused on the relationship between historical events and ideologies, he viewed humanism as an important turning point in the history of Western philosophy, that is, as a transition to modernity.

In his view, the Italian Renaissance was essentially a movement to elevate and transform the culture and values of ancient peoples within the historical environment of Renaissance Italy.

In particular, the achievements of Renaissance humanists were philology, which they called 'grammatica' - philology at that time was not philology in the narrow sense of the modern day, but rather 'philosophy' in the broad sense of presenting a new perspective on humans and the world.

Naturally, it was based on a dislike for scholastic philosophy, which was mired in metaphysics and theology, and turned towards concrete studies - through which he saw the practice of a new kind of philosophy, or philosophy - in a broad sense - which was a new transformation of the ancient concept of 'philosophy' - the love of wisdom.

In short, Garin argued for ‘very practical philosophizing’ (proprio effettivo filosofare) or ‘philology as philosophy.’

Christeller is the scholar who stands in opposition to Garin, who regards Renaissance humanism as a new 'philosophy' that rebelled against scholastic philosophy (or traditional philosophy).

On almost every point of history and philosophy, Garin and Christeller are polar opposites.

For Christeller, Renaissance humanists were heirs to medieval rhetoricians, and so they believed that the best way to achieve eloquence was to imitate the style of classical works such as Cicero.

That is, most of these humanists were 'professional rhetoricians' who studied the classics and explored classical linguistics, either as clerks in monarchies or republics or as teachers of grammar and rhetoric in universities or lower schools.

Therefore, in his view, Renaissance humanism is “a cultural and educational program that emphasizes and develops the humanities rather than a philosophical tendency or system,” and humanists are “not philosophers at all.”

The author of this book re-establishes Renaissance humanism based on philosophy as a way of life.

Currently, the study of Renaissance humanism is showing a trend in which the 'philosophical school' following Christeller is attacking the solid fortress of the 'rhetorical school' while the 'civic values' emphasized by Baron still form one axis.

The 'philosophical school' is roughly divided into two branches (though the two are closely related): one is that which seeks to 'philosophize' or 'philosophy as philosophy' in a humanistic way, and the other is that humanist philosophy aims for 'philosophy as a way of life' rather than the dialectics of traditional scholastic philosophy.

According to Pierre Hadot, the French philosopher who advocated 'philosophy as a way of life', it is "a way of being-in-the-world that must be practiced at every moment with the goal of transforming one's entire life."

Philosophy was originally conceived as the love of wisdom, and wisdom “does not merely enable us to know, but makes us ‘be’ in a different way.” The author of this book, Selenza, follows Addo’s model of philosophy and argues that during the Renaissance, the word ‘philosopher’ was used in a broad sense, and that the philosophy that humanists conceived of was the search for wisdom in all areas of life.

This idea has persisted since ancient times, and from the end of the 18th century, a theoretical and dialectical philosophy became mainstream.

Thus, Petrarch, while criticizing Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, said that the essence of philosophy is 'care for the soul' (Alberti followed suit), Leonardo Bruni intentionally omitted Aristotle's metaphysics to make him a humanist, and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola considered attitude toward life to be one aspect of a true philosopher.

They all pursued a Socratic view on how to live.

With these points in mind, the author emphasizes that philosophy is not simply about pursuing knowledge, but about transforming oneself through that knowledge; that is, it is not about clinging to logical consistency and commentary alone, and that the meaning of Renaissance humanism must be sought in that respect.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 10, 2025

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 692 pages | 153*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788964453025

- ISBN10: 8964453026

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)