History of the French Revolution

|

Description

Book Introduction

“The French Revolution opened the curtain on the modern world.” ― Albert Soboul

A magnificent narrative of the French Revolution, depicted with unparalleled clarity.

A modern classic that elevated Albert Soboulle to the position of the greatest historian of the French Revolution.

Albert Soboul (1914-1982) was an outstanding revolutionary historian who broadened and deepened our knowledge of the French Revolution.

Sobul's masterpiece, "History of the French Revolution," has been translated into numerous languages and is a classic work read around the world. It is also recognized as the best introductory book on the history of the French Revolution, culminating in the achievements of research up to that time.

Sobule inherited the tradition of French revolutionary history studies from Jean Jaures, Albert Mathiez, and Georges Lefebvre, and compiled the true nature of the French Revolution as a great social revolution on a grand scale.

Sobule answered the real questions of the revolution through a delicate and passionate exploration of the ten years of the French Revolution.

How was such a profound transformation possible? How did the leaders of the revolution change the world and transform themselves? This book, in a clear and unpretentious style, vividly illustrates the whys and hows of the French Revolution.

This book, an excellent guide to the French Revolution accessible to everyone, will enable readers to grasp the unfolding of the French Revolution and its historical and current significance.

A magnificent narrative of the French Revolution, depicted with unparalleled clarity.

A modern classic that elevated Albert Soboulle to the position of the greatest historian of the French Revolution.

Albert Soboul (1914-1982) was an outstanding revolutionary historian who broadened and deepened our knowledge of the French Revolution.

Sobul's masterpiece, "History of the French Revolution," has been translated into numerous languages and is a classic work read around the world. It is also recognized as the best introductory book on the history of the French Revolution, culminating in the achievements of research up to that time.

Sobule inherited the tradition of French revolutionary history studies from Jean Jaures, Albert Mathiez, and Georges Lefebvre, and compiled the true nature of the French Revolution as a great social revolution on a grand scale.

Sobule answered the real questions of the revolution through a delicate and passionate exploration of the ten years of the French Revolution.

How was such a profound transformation possible? How did the leaders of the revolution change the world and transform themselves? This book, in a clear and unpretentious style, vividly illustrates the whys and hows of the French Revolution.

This book, an excellent guide to the French Revolution accessible to everyone, will enable readers to grasp the unfolding of the French Revolution and its historical and current significance.

index

Preface to the Revised Edition (Claude Majoric)

preface

Introduction: The Crisis of the Old Regime

Chapter 1: Social Crisis

Chapter 2: The Crisis of the System

Chapter 3: The Prologue to the Bourgeois Revolution: The Revolt of the Privileged Classes

Part 1: People, King, and Law

- Bourgeois Revolution and Popular Movement (1789–1792)

Chapter 1: Bourgeois Revolution and the Collapse of the Old Regime

Chapter 2: The Constituent Assembly: The Failure of Compromise

Chapter 3: The Bourgeoisie of the Constituent Assembly and the Reconstruction of France

Chapter 4: The Constituent Assembly and the King's Escape

Chapter 5: The Legislative Assembly: War and the Overthrow of the Throne

Part 2: The Premises of Freedom

- Revolutionary government and popular movement (1792-1795)

Chapter 1: The End of the Legislative Assembly: The Revolution's Advance and National Defense

Chapter 2: The Girondin National Convention: The Bankruptcy of the Liberal Bourgeoisie

Chapter 3: The National Convention of the Mountain Faction: Popular Movement and the Dictatorship of Public Safety

Chapter 4: Victory and the Fall of the Revolutionary Government

Chapter 5: The Thermidorian National Convention: Bourgeois Reaction and the End of the Popular Movement

Part 3: A Country Ruled by the Legacy

- Consolidation of the bourgeois republic and society (1795–1799)

Chapter 1: The End of the Thermidorian National Convention: The Treaties of 1795 and the Constitution of Year III

Chapter 2 The First Presidential Government: The Failure of Liberal Stabilization

Chapter 3: The Second Directory: The End of the Bourgeois Republic

Conclusion: Revolution and Modern France

new society

bourgeois state

National unity and equality of rights

Legacy of the Revolution

Appendix 1: The Revolutionary Crowd: Collective Violence and Social Relations

Appendix 2 What is Revolution?

Translator's Note

French Revolution Chronology

Search

preface

Introduction: The Crisis of the Old Regime

Chapter 1: Social Crisis

Chapter 2: The Crisis of the System

Chapter 3: The Prologue to the Bourgeois Revolution: The Revolt of the Privileged Classes

Part 1: People, King, and Law

- Bourgeois Revolution and Popular Movement (1789–1792)

Chapter 1: Bourgeois Revolution and the Collapse of the Old Regime

Chapter 2: The Constituent Assembly: The Failure of Compromise

Chapter 3: The Bourgeoisie of the Constituent Assembly and the Reconstruction of France

Chapter 4: The Constituent Assembly and the King's Escape

Chapter 5: The Legislative Assembly: War and the Overthrow of the Throne

Part 2: The Premises of Freedom

- Revolutionary government and popular movement (1792-1795)

Chapter 1: The End of the Legislative Assembly: The Revolution's Advance and National Defense

Chapter 2: The Girondin National Convention: The Bankruptcy of the Liberal Bourgeoisie

Chapter 3: The National Convention of the Mountain Faction: Popular Movement and the Dictatorship of Public Safety

Chapter 4: Victory and the Fall of the Revolutionary Government

Chapter 5: The Thermidorian National Convention: Bourgeois Reaction and the End of the Popular Movement

Part 3: A Country Ruled by the Legacy

- Consolidation of the bourgeois republic and society (1795–1799)

Chapter 1: The End of the Thermidorian National Convention: The Treaties of 1795 and the Constitution of Year III

Chapter 2 The First Presidential Government: The Failure of Liberal Stabilization

Chapter 3: The Second Directory: The End of the Bourgeois Republic

Conclusion: Revolution and Modern France

new society

bourgeois state

National unity and equality of rights

Legacy of the Revolution

Appendix 1: The Revolutionary Crowd: Collective Violence and Social Relations

Appendix 2 What is Revolution?

Translator's Note

French Revolution Chronology

Search

Into the book

In the 18th century, living conditions for the urban poor deteriorated.

The increase in urban population along with rising prices has exacerbated the imbalance between the cost of living and wages.

In the late 18th century, even the impoverishment of the wage earners began to appear.

… … The fundamental problem of the common people’s livelihood was wages and purchasing power.

The pressure of inflation has been felt unevenly across different segments of the population, depending on the composition of their cost of living.

The rise in grain prices was most severe, especially among the lower classes, who naturally suffered the most, as the population grew and bread accounted for a very large portion of the cost of living.

… …

It was seasonal price fluctuations that led to the tragic results.

In the run-up to 1789, amidst the general inflation, food expenditures already accounted for 58 percent of the expenditures of common households, and by 1789, this had soared to 88 percent.

Disposable income other than food expenses is only 12 percent.

The surge in prices did not have much of an impact on the wealthy, but it hit the poor hard.

--- p.61~62

The people's fundamental demand was still bread.

The extreme political aggression of the masses in 1788-1789 was also due to the severity of the economic crisis that was making their livelihood increasingly difficult.

The riots that broke out in most cities in 1789 were caused by poverty, and their first effect was a reduction in the price of bread.

The crisis in ancien régime France was essentially an agrarian crisis.

Whenever crop failures or crop failures continued, an agricultural crisis invariably occurred.

Then, grain prices rose dramatically, and the purchasing power of the majority of small farmers who had to buy grain decreased.

In this way, the agricultural crisis spread to industrial production.

The agrarian crisis of the entire 18th century reached its peak in 1788.

That winter, famine struck and begging increased rapidly due to unemployment.

These hungry unemployed people formed one axis of the revolutionary crowd.

--- p.64

From poverty and group mentality, 'riots' and rebellions erupted.

On April 28, 1789, the first riot broke out in Paris against the wallpaper manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon and the limestone manufacturer François Henriot.

The two men were accused of making unscrupulous remarks about the poverty of the people at the electoral college.

Leveyong said that a worker can live comfortably on 15 sous a day.

There were protests on April 27th, and on the 28th the homes of two manufacturers were looted.

When the police chief sent in the military, the rioters resisted and there were deaths.

Thus, the first revolutionary uprising was clearly economic and social in origin, not political.

The people had no clear views on political issues.

The reason they took action was because there were economic and social reasons.

However, these popular unrests were bound to have political consequences that threatened power.

--- p.65

Rousseau, with the soul of a commoner, stood against the tide of the century.

In his first essay, [If the Revival of Science and Arts Contributed to the Purification of Morals] (1750), he criticized the civilization of his time and defended those who had not benefited from it.

“Luxury feeds a hundred paupers in our towns, but in fact kills a hundred thousand in our country.” In his second essay (Discourse on the Origin of Inequality among Men) he attacked property rights.

And in The Social Contract, he presented the theory of popular sovereignty.

While Montesquieu and Voltaire confined power to the privileged classes and the upper bourgeoisie respectively, Rousseau liberated the lowly and gave power to the entire people.

Rousseau assigned the role of the state to restrain the abuse of private property rights and maintain social balance through inheritance legislation and progressive taxation.

This call for equality in the social as well as the political sphere was new in the 18th century.

--- p.82

The French Revolution, according to Jean Jaurès, was not a “bourgeois and conservative” revolution in the narrow sense, like the English “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, but a “bourgeois and democratic” revolution in the broad sense.

The great revolution took on this character because it was supported by the masses of people who, driven by a hatred for privilege and unable to endure hunger, yearned to be free from the oppression of feudalism.

One of the fundamental tasks of the Great Revolution was to destroy feudalism and liberate the peasants and their land.

Not only the total economic crisis at the end of the old regime, but more fundamentally, the structure and contradictions of the old society explain these characteristics of the revolution.

The French Revolution was truly a bourgeois revolution.

However, it was a bourgeois revolution supported by the people, especially the peasants.

--- p.132~133

The provinces watched the Third Estate's struggle for privileged status with the same uneasy eye as the capital.

The news of Necker's dismissal caused as much excitement in Paris as in the rest of the country.

News of the fall of the Bastille reached Paris between July 16th and 19th, depending on distance from Paris.

The news sparked a frenzy and spurred movements that had been emerging in several cities since early July.

The 'urban revolutions' actually began in early July, as in Rouen, due to food shortages, and continued for nearly a month, as in Hoche and Bourges, until August.

In Dijon, the news of Necker's dismissal became the trigger for revolution, and in Montauban, the news of the fall of the Bastille became the trigger for revolution.

… …

Whatever the nature of these urban revolutions, the results were the same everywhere.

The monarchy was abolished, centralization collapsed, almost all governors gave up their posts, and tax collection ceased.

In the words of the time, “the king, the high court, the army, and the police ceased to exist.” New municipalities took over the old powers.

Local autonomy, which had long been suppressed by absolutism, began to function freely, and the vitality of local governments was enriched again.

France became an autonomous community.

--- p.169~171

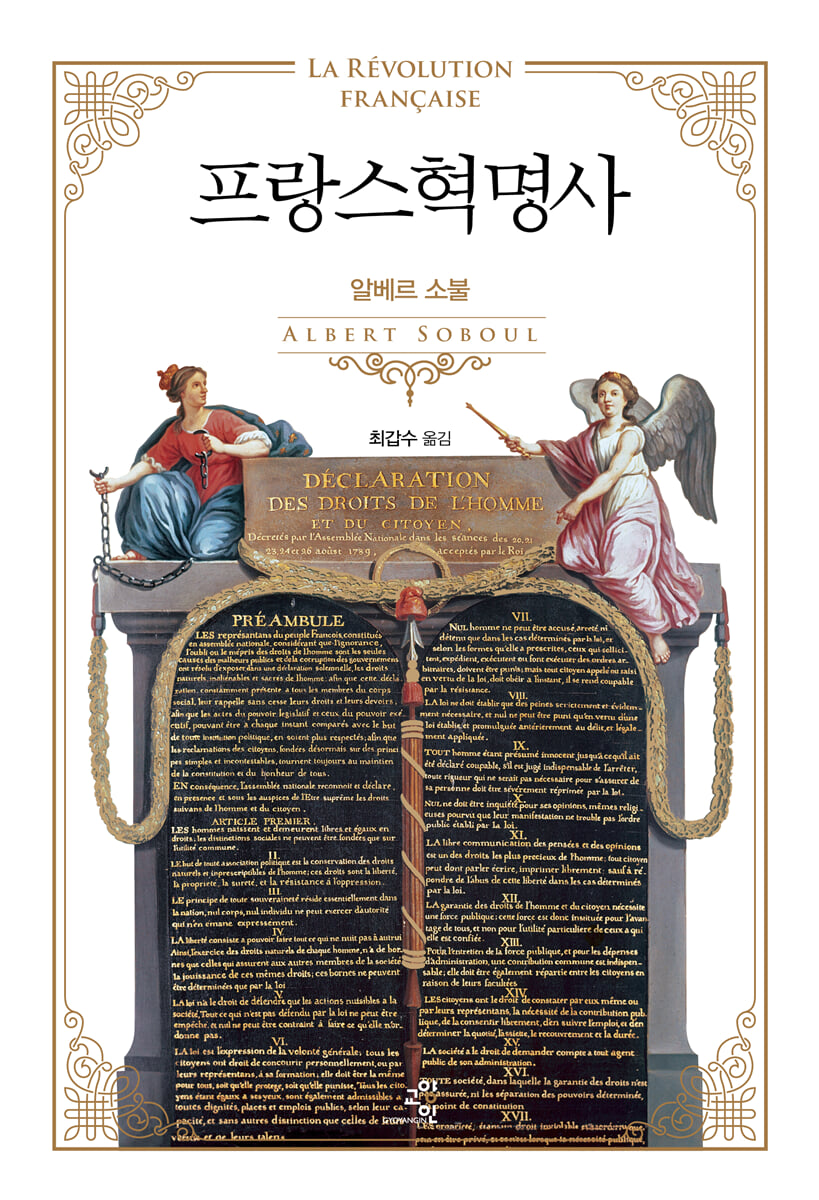

On August 1, 1789, Parliament resumed its debate.

The debate raged on this very point, as the delegates disagreed over the need to draft a declaration of human rights.

Some speakers even questioned the very timeliness of the declaration.

Moderates, like Pierre-Victor Malouet, who were alarmed by the disorder, considered the Declaration of Rights useless or even dangerous.

Those like Father Gregoire hoped to add a declaration of obligations to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

Finally, on the morning of the 4th, the National Assembly decided to insert the Declaration of Rights at the beginning of the Constitution.

The discussion progressed slowly.

… … On August 26, 1789, Parliament adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen became a 'death certificate of the old regime', an implicit condemnation of the evils of a privileged society and monarchy.

But at the same time, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, inspired by the doctrines of the Enlightenment, expressed the ideals of the bourgeoisie and laid the foundations of a new social order applicable not only to France but to all humanity.

--- p.179~180

Those who were called 'sans-culottes' at the time of the revolution were this old popular category that was the basic element that constituted the revolutionary crowd.

… … On April 10, 1793, Pétion said to the National Convention:

“When we speak of sans-culottes, we do not mean all citizens except the nobles and the privileged.

Rather, to distinguish those who have not, they are called sans-culottes.”

The sans-culottes defined themselves by their actions, their hostility to the privileged classes, to commerce, to wealth, if not to affluence.

… … A counter-revolutionary worker could not be a good sans-culottes.

The patriotic bourgeoisie gladly qualifies as sans-culottes.

The social dimension becomes clear when it is defined politically.

The two were inseparable.

The key here was not lip service to patriotism or a mere mentality, but a political attitude.

The sans-culottes took part in all the great events that took place during the Revolution.

--- p.747

Although the revolutionary government, faced with an imminent danger, agreed to an alliance with the sans-culottes and made some concessions to maintain that relationship, it by no means accepted the social aims or political methods of sans-culottes democracy.

Moreover, for the two government committees, it was justifiable, in the light of the struggle against the Great Alliance and the counter-revolution and in the light of the political conceptions of the two committees, to control the popular organizations and integrate them into the Jacobin framework of the bourgeois revolution.

So when the Cordelier faction's opposition threatened this equilibrium, the revolutionary government responded with repressive measures.

However, the sans-culottes began to distrust the revolutionary government after witnessing the elimination of [Pére Duchene] and the Cordeliers, who had represented and supported their aspirations.

The revolutionary government also removed the party leader, but it was in vain.

The repressive measures that followed these high-profile trials, though limited, instilled fear in the fighters and paralyzed political activity in the district.

Direct and friendly contact between the revolutionary authorities and the old sans-culottes was now severed.

Soon after, Saint-Just wrote, “The revolution is frozen.”

--- p.440~441

We can obtain an accurate picture of the composition of the revolutionary masses, which are at once heterogeneous and unified wholes.

These are the 'common people' of Paris.

… … These revolutionary crowds were neither marginalized or “independent” individuals with severed social ties, nor were they proletarians without stable jobs, prone to disorder due to poverty, easily mobilized by agitators, and lacking professional technical training.

They were artisans and journeymen, clerks, shopkeepers and retailers – a collection of small business owners and wage earners who were equally agitated by the rising cost of living and the political crisis.

In this way, sans-culottes took up an overwhelming proportion.

But there were also small numbers of 'bourgeois', rentiers and free professionals who took part in the uprising.

These included the fall of the Bastille, the Champ de Mars (July 17, 1791), the attack on the Tuileries Palace, and the uprising that erupted in Prairie in 1793.

Women played a particularly important role in the March on Versailles, the food riots and looting of 1792–1793, and the Prairie Uprising.

--- p.744~745

Revolution, it cannot be forced 'from above'.

If ‘reform’ can be given ‘from above,’ revolution is inevitably forced ‘from below.’

Reforms do not shake the basic structures of society, but rather support them for the continued benefit of dominant social categories.

Reform becomes clear about its raison d'être within the framework of the existing society it seeks to strengthen.

Moreover, reform is not a revolution that extends over a long period of time, and reform and revolution are distinguished not by their length of time but by their content.

Reform or revolution? The question here isn't whether to choose a faster or slower path that leads to the same result, but to clarify the goal: the creation of a new society or a superficial revision of the old.

The increase in urban population along with rising prices has exacerbated the imbalance between the cost of living and wages.

In the late 18th century, even the impoverishment of the wage earners began to appear.

… … The fundamental problem of the common people’s livelihood was wages and purchasing power.

The pressure of inflation has been felt unevenly across different segments of the population, depending on the composition of their cost of living.

The rise in grain prices was most severe, especially among the lower classes, who naturally suffered the most, as the population grew and bread accounted for a very large portion of the cost of living.

… …

It was seasonal price fluctuations that led to the tragic results.

In the run-up to 1789, amidst the general inflation, food expenditures already accounted for 58 percent of the expenditures of common households, and by 1789, this had soared to 88 percent.

Disposable income other than food expenses is only 12 percent.

The surge in prices did not have much of an impact on the wealthy, but it hit the poor hard.

--- p.61~62

The people's fundamental demand was still bread.

The extreme political aggression of the masses in 1788-1789 was also due to the severity of the economic crisis that was making their livelihood increasingly difficult.

The riots that broke out in most cities in 1789 were caused by poverty, and their first effect was a reduction in the price of bread.

The crisis in ancien régime France was essentially an agrarian crisis.

Whenever crop failures or crop failures continued, an agricultural crisis invariably occurred.

Then, grain prices rose dramatically, and the purchasing power of the majority of small farmers who had to buy grain decreased.

In this way, the agricultural crisis spread to industrial production.

The agrarian crisis of the entire 18th century reached its peak in 1788.

That winter, famine struck and begging increased rapidly due to unemployment.

These hungry unemployed people formed one axis of the revolutionary crowd.

--- p.64

From poverty and group mentality, 'riots' and rebellions erupted.

On April 28, 1789, the first riot broke out in Paris against the wallpaper manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon and the limestone manufacturer François Henriot.

The two men were accused of making unscrupulous remarks about the poverty of the people at the electoral college.

Leveyong said that a worker can live comfortably on 15 sous a day.

There were protests on April 27th, and on the 28th the homes of two manufacturers were looted.

When the police chief sent in the military, the rioters resisted and there were deaths.

Thus, the first revolutionary uprising was clearly economic and social in origin, not political.

The people had no clear views on political issues.

The reason they took action was because there were economic and social reasons.

However, these popular unrests were bound to have political consequences that threatened power.

--- p.65

Rousseau, with the soul of a commoner, stood against the tide of the century.

In his first essay, [If the Revival of Science and Arts Contributed to the Purification of Morals] (1750), he criticized the civilization of his time and defended those who had not benefited from it.

“Luxury feeds a hundred paupers in our towns, but in fact kills a hundred thousand in our country.” In his second essay (Discourse on the Origin of Inequality among Men) he attacked property rights.

And in The Social Contract, he presented the theory of popular sovereignty.

While Montesquieu and Voltaire confined power to the privileged classes and the upper bourgeoisie respectively, Rousseau liberated the lowly and gave power to the entire people.

Rousseau assigned the role of the state to restrain the abuse of private property rights and maintain social balance through inheritance legislation and progressive taxation.

This call for equality in the social as well as the political sphere was new in the 18th century.

--- p.82

The French Revolution, according to Jean Jaurès, was not a “bourgeois and conservative” revolution in the narrow sense, like the English “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, but a “bourgeois and democratic” revolution in the broad sense.

The great revolution took on this character because it was supported by the masses of people who, driven by a hatred for privilege and unable to endure hunger, yearned to be free from the oppression of feudalism.

One of the fundamental tasks of the Great Revolution was to destroy feudalism and liberate the peasants and their land.

Not only the total economic crisis at the end of the old regime, but more fundamentally, the structure and contradictions of the old society explain these characteristics of the revolution.

The French Revolution was truly a bourgeois revolution.

However, it was a bourgeois revolution supported by the people, especially the peasants.

--- p.132~133

The provinces watched the Third Estate's struggle for privileged status with the same uneasy eye as the capital.

The news of Necker's dismissal caused as much excitement in Paris as in the rest of the country.

News of the fall of the Bastille reached Paris between July 16th and 19th, depending on distance from Paris.

The news sparked a frenzy and spurred movements that had been emerging in several cities since early July.

The 'urban revolutions' actually began in early July, as in Rouen, due to food shortages, and continued for nearly a month, as in Hoche and Bourges, until August.

In Dijon, the news of Necker's dismissal became the trigger for revolution, and in Montauban, the news of the fall of the Bastille became the trigger for revolution.

… …

Whatever the nature of these urban revolutions, the results were the same everywhere.

The monarchy was abolished, centralization collapsed, almost all governors gave up their posts, and tax collection ceased.

In the words of the time, “the king, the high court, the army, and the police ceased to exist.” New municipalities took over the old powers.

Local autonomy, which had long been suppressed by absolutism, began to function freely, and the vitality of local governments was enriched again.

France became an autonomous community.

--- p.169~171

On August 1, 1789, Parliament resumed its debate.

The debate raged on this very point, as the delegates disagreed over the need to draft a declaration of human rights.

Some speakers even questioned the very timeliness of the declaration.

Moderates, like Pierre-Victor Malouet, who were alarmed by the disorder, considered the Declaration of Rights useless or even dangerous.

Those like Father Gregoire hoped to add a declaration of obligations to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

Finally, on the morning of the 4th, the National Assembly decided to insert the Declaration of Rights at the beginning of the Constitution.

The discussion progressed slowly.

… … On August 26, 1789, Parliament adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen became a 'death certificate of the old regime', an implicit condemnation of the evils of a privileged society and monarchy.

But at the same time, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, inspired by the doctrines of the Enlightenment, expressed the ideals of the bourgeoisie and laid the foundations of a new social order applicable not only to France but to all humanity.

--- p.179~180

Those who were called 'sans-culottes' at the time of the revolution were this old popular category that was the basic element that constituted the revolutionary crowd.

… … On April 10, 1793, Pétion said to the National Convention:

“When we speak of sans-culottes, we do not mean all citizens except the nobles and the privileged.

Rather, to distinguish those who have not, they are called sans-culottes.”

The sans-culottes defined themselves by their actions, their hostility to the privileged classes, to commerce, to wealth, if not to affluence.

… … A counter-revolutionary worker could not be a good sans-culottes.

The patriotic bourgeoisie gladly qualifies as sans-culottes.

The social dimension becomes clear when it is defined politically.

The two were inseparable.

The key here was not lip service to patriotism or a mere mentality, but a political attitude.

The sans-culottes took part in all the great events that took place during the Revolution.

--- p.747

Although the revolutionary government, faced with an imminent danger, agreed to an alliance with the sans-culottes and made some concessions to maintain that relationship, it by no means accepted the social aims or political methods of sans-culottes democracy.

Moreover, for the two government committees, it was justifiable, in the light of the struggle against the Great Alliance and the counter-revolution and in the light of the political conceptions of the two committees, to control the popular organizations and integrate them into the Jacobin framework of the bourgeois revolution.

So when the Cordelier faction's opposition threatened this equilibrium, the revolutionary government responded with repressive measures.

However, the sans-culottes began to distrust the revolutionary government after witnessing the elimination of [Pére Duchene] and the Cordeliers, who had represented and supported their aspirations.

The revolutionary government also removed the party leader, but it was in vain.

The repressive measures that followed these high-profile trials, though limited, instilled fear in the fighters and paralyzed political activity in the district.

Direct and friendly contact between the revolutionary authorities and the old sans-culottes was now severed.

Soon after, Saint-Just wrote, “The revolution is frozen.”

--- p.440~441

We can obtain an accurate picture of the composition of the revolutionary masses, which are at once heterogeneous and unified wholes.

These are the 'common people' of Paris.

… … These revolutionary crowds were neither marginalized or “independent” individuals with severed social ties, nor were they proletarians without stable jobs, prone to disorder due to poverty, easily mobilized by agitators, and lacking professional technical training.

They were artisans and journeymen, clerks, shopkeepers and retailers – a collection of small business owners and wage earners who were equally agitated by the rising cost of living and the political crisis.

In this way, sans-culottes took up an overwhelming proportion.

But there were also small numbers of 'bourgeois', rentiers and free professionals who took part in the uprising.

These included the fall of the Bastille, the Champ de Mars (July 17, 1791), the attack on the Tuileries Palace, and the uprising that erupted in Prairie in 1793.

Women played a particularly important role in the March on Versailles, the food riots and looting of 1792–1793, and the Prairie Uprising.

--- p.744~745

Revolution, it cannot be forced 'from above'.

If ‘reform’ can be given ‘from above,’ revolution is inevitably forced ‘from below.’

Reforms do not shake the basic structures of society, but rather support them for the continued benefit of dominant social categories.

Reform becomes clear about its raison d'être within the framework of the existing society it seeks to strengthen.

Moreover, reform is not a revolution that extends over a long period of time, and reform and revolution are distinguished not by their length of time but by their content.

Reform or revolution? The question here isn't whether to choose a faster or slower path that leads to the same result, but to clarify the goal: the creation of a new society or a superficial revision of the old.

--- p.776

Publisher's Review

Translated by the country's leading authority on the history of the French Revolution

The definitive edition of Albert Soboul's Revolutionary History series

《History of the French Revolution》 is a revised edition of 《Introduction to the History of the French Revolution》 (published in 1962), the first fruit of Albert Soboul's great academic work.

Although a popular edition of "An Introduction to the History of the French Revolution" was published in Korea in 1984, this is the first time that a revised edition has been published in its entirety.

Professor Choi Gap-su of the Department of Western History at Seoul National University, the leading authority on the history of the French Revolution in Korea, has translated it into Korean.

Since the mid-1960s, with the accumulation of empirical research results that challenged traditional interpretations of the French Revolution, Sobul felt the need to revise "Introduction to the History of the French Revolution."

In 1982, Sobul began a comprehensive revision project, but passed away that year due to sudden deterioration in health.

Following Sobul's work of revising and adding content throughout the book, his disciples organized the text and included as appendices two essays, [Revolutionary Crowd] and [What is Revolution?], which Sobul had published a year before his death and sketched out as a blueprint for revision.

This completed the 'final comprehensive introduction to the history of the French Revolution', representing the traditional French historical scholarship on the study of the French Revolution.

《History of the French Revolution》 is composed of five parts.

The 'Introduction' section details the social background that led to the French Revolution, based on Sobul's research on economic trends in ancien régime France in the late 18th century.

In 'Parts 1, 2, and 3', the progress and rise and fall of the French Revolution over the past ten years, from 1789, when the revolution began, to 1799, when the Republic fell and the Directory came to power, are depicted in a compelling way, focusing on the main subjects of the revolution, the bourgeoisie and the people.

The final 'Conclusion' section shows the specificity and modern significance of the French Revolution by addressing the issues that the French Revolution raised not only in France but also in modern society.

Why should I still read the book?

“The French Revolution lost popularity.

Although its historical significance is still recognized, its reputation has declined.

“For many in the public and academia, the French Revolution was the harbinger of violence, terror, totalitarianism, and even genocide in the modern world.” This is the testimony of a representative of the Anglo-American revolutionary history community upon taking office as president of the American Historical Association (AHA).

What a tremendous reversal of significance this is! … … Not all revolutions end in the guillotine.

Revolutions have been classified as 'good' and 'bad' revolutions.

The British and American Revolutions were considered 'good' revolutions that did not involve violence or bloodshed, while the French, Russian, and all other Third World revolutions were considered 'bad' revolutions that resulted in massive violations of human rights.

… …

What we find in this series of revisionary interpretations is a conformism that dismisses any fundamental questioning of the existing order (especially capitalism).

And it goes without saying that all academic attempts to disconnect the past from the present and future are merely ideological offensives and not true history.

This is precisely why we still need to read the Small Buddha.

History has as its academic mission to reflect on our present by looking at the past in a strange way.

Therefore, the act of dismissing the revolution, the ‘driving force of history,’ as a counterrevolution is ahistorical and even anti-historical, no matter how much it is dressed up as academicism.

This book by Sobul constantly asks the question of what the past of the French Revolution, its protagonists and even its victims, has present-day meaning.

? In the 'Translator's Note'

Who created the French Revolution?

《History of the French Revolution》 reconstructs the French Revolution focusing on the bourgeoisie of the old regime and the urban people and peasants who existed behind the scenes of the revolution.

It reveals that although various types of bourgeoisie led the revolution, the people of both cities and rural areas entered the revolutionary stage in large numbers amid the divisions of the ruling class.

Albert Soboul, who followed in the footsteps of Jean Jaurès, who had described the French Revolution from the perspective of the people and thus achieved a "historiography from below (d'en bas)", proved through a tremendous amount of historical research that the "peasant revolution" and the "popular revolution" existed.

It shows the true nature of the French Revolution as a great social revolution in which the bourgeoisie was the main character, but the urban masses and peasants played supporting roles with strong personalities.

What is revolution?

In his History of the French Revolution, Albert Soboul clearly defines the concept of revolution and explains the essential characteristics of the French Revolution.

According to him, revolution means not only the destruction of the existing state apparatus, but also a fundamental transformation of the social relations and political structures that govern the state apparatus.

That is, the goal of the revolution is not to improve the old order or alleviate its evils, but to abolish privileges and feudalism and create a new social order.

The causes of the French Revolution were deeply rooted in the contradictory realities that the French people experienced during the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

In the course of the revolution, old social relations were destroyed in the course of the class struggle between the privileged and the common classes, and after the revolution, institutions such as democracy, which were essentially different from the previous absolute monarchy, gained power.

The small fire shows how a new social force, the bourgeoisie, with the support and restraint of the urban masses and rural peasantry, created modern society and the modern state through revolution.

The definitive edition of Albert Soboul's Revolutionary History series

《History of the French Revolution》 is a revised edition of 《Introduction to the History of the French Revolution》 (published in 1962), the first fruit of Albert Soboul's great academic work.

Although a popular edition of "An Introduction to the History of the French Revolution" was published in Korea in 1984, this is the first time that a revised edition has been published in its entirety.

Professor Choi Gap-su of the Department of Western History at Seoul National University, the leading authority on the history of the French Revolution in Korea, has translated it into Korean.

Since the mid-1960s, with the accumulation of empirical research results that challenged traditional interpretations of the French Revolution, Sobul felt the need to revise "Introduction to the History of the French Revolution."

In 1982, Sobul began a comprehensive revision project, but passed away that year due to sudden deterioration in health.

Following Sobul's work of revising and adding content throughout the book, his disciples organized the text and included as appendices two essays, [Revolutionary Crowd] and [What is Revolution?], which Sobul had published a year before his death and sketched out as a blueprint for revision.

This completed the 'final comprehensive introduction to the history of the French Revolution', representing the traditional French historical scholarship on the study of the French Revolution.

《History of the French Revolution》 is composed of five parts.

The 'Introduction' section details the social background that led to the French Revolution, based on Sobul's research on economic trends in ancien régime France in the late 18th century.

In 'Parts 1, 2, and 3', the progress and rise and fall of the French Revolution over the past ten years, from 1789, when the revolution began, to 1799, when the Republic fell and the Directory came to power, are depicted in a compelling way, focusing on the main subjects of the revolution, the bourgeoisie and the people.

The final 'Conclusion' section shows the specificity and modern significance of the French Revolution by addressing the issues that the French Revolution raised not only in France but also in modern society.

Why should I still read the book?

“The French Revolution lost popularity.

Although its historical significance is still recognized, its reputation has declined.

“For many in the public and academia, the French Revolution was the harbinger of violence, terror, totalitarianism, and even genocide in the modern world.” This is the testimony of a representative of the Anglo-American revolutionary history community upon taking office as president of the American Historical Association (AHA).

What a tremendous reversal of significance this is! … … Not all revolutions end in the guillotine.

Revolutions have been classified as 'good' and 'bad' revolutions.

The British and American Revolutions were considered 'good' revolutions that did not involve violence or bloodshed, while the French, Russian, and all other Third World revolutions were considered 'bad' revolutions that resulted in massive violations of human rights.

… …

What we find in this series of revisionary interpretations is a conformism that dismisses any fundamental questioning of the existing order (especially capitalism).

And it goes without saying that all academic attempts to disconnect the past from the present and future are merely ideological offensives and not true history.

This is precisely why we still need to read the Small Buddha.

History has as its academic mission to reflect on our present by looking at the past in a strange way.

Therefore, the act of dismissing the revolution, the ‘driving force of history,’ as a counterrevolution is ahistorical and even anti-historical, no matter how much it is dressed up as academicism.

This book by Sobul constantly asks the question of what the past of the French Revolution, its protagonists and even its victims, has present-day meaning.

? In the 'Translator's Note'

Who created the French Revolution?

《History of the French Revolution》 reconstructs the French Revolution focusing on the bourgeoisie of the old regime and the urban people and peasants who existed behind the scenes of the revolution.

It reveals that although various types of bourgeoisie led the revolution, the people of both cities and rural areas entered the revolutionary stage in large numbers amid the divisions of the ruling class.

Albert Soboul, who followed in the footsteps of Jean Jaurès, who had described the French Revolution from the perspective of the people and thus achieved a "historiography from below (d'en bas)", proved through a tremendous amount of historical research that the "peasant revolution" and the "popular revolution" existed.

It shows the true nature of the French Revolution as a great social revolution in which the bourgeoisie was the main character, but the urban masses and peasants played supporting roles with strong personalities.

What is revolution?

In his History of the French Revolution, Albert Soboul clearly defines the concept of revolution and explains the essential characteristics of the French Revolution.

According to him, revolution means not only the destruction of the existing state apparatus, but also a fundamental transformation of the social relations and political structures that govern the state apparatus.

That is, the goal of the revolution is not to improve the old order or alleviate its evils, but to abolish privileges and feudalism and create a new social order.

The causes of the French Revolution were deeply rooted in the contradictory realities that the French people experienced during the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

In the course of the revolution, old social relations were destroyed in the course of the class struggle between the privileged and the common classes, and after the revolution, institutions such as democracy, which were essentially different from the previous absolute monarchy, gained power.

The small fire shows how a new social force, the bourgeoisie, with the support and restraint of the urban masses and rural peasantry, created modern society and the modern state through revolution.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 20, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 812 pages | 874g | 153*224*40mm

- ISBN13: 9791193154328

- ISBN10: 1193154324

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)