Portrait of a Young People

|

Description

Book Introduction

How China's "next generation" became what it is today

What kind of world will they create in the future?

The reality faced by two generations of young people in China from 1996 to the present

The most human journalism, portrayed with deep empathy and sincerity.

I said that I think young people are risk-averse because they are only children who feel pressured to succeed.

They also said that they were much better educated and more aware of the outside world than previous generations.

“But I don’t know what this means for the future,” I said.

“Maybe they will figure out a way to change the system.

But maybe we just figure out how to adapt to the system.”

I looked at the young faces surrounding me and asked:

“What do you think?”

“We’ll adapt,” one girl said, and several nodded.

“It’s easy to get angry, but it’s easy to forget anger,” said another student.

But Serena, who was sitting at the back of the group, said this.

“We will change the system.”

_From page 522 of the text

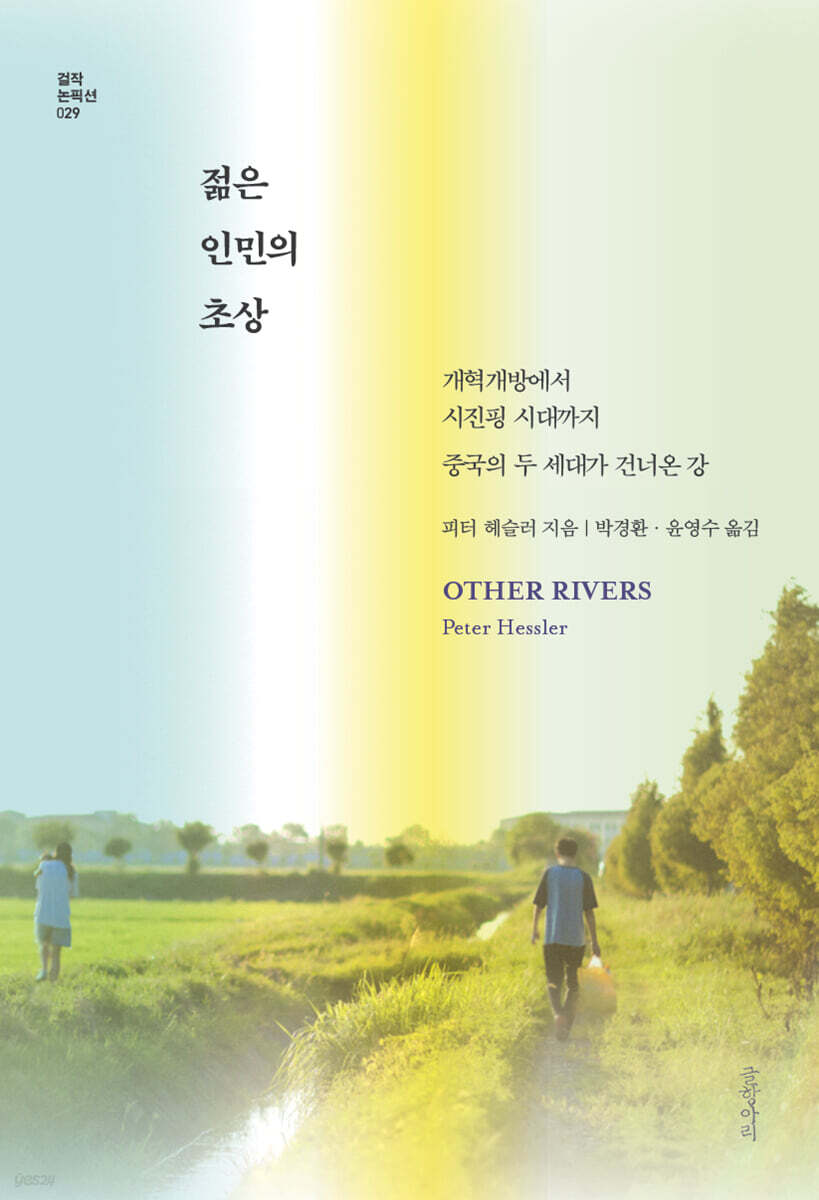

Peter Hessler's 2024 new book, Portrait of a Young People (original title: Other Rivers), has been translated and published as the 29th book in the Masterpiece Nonfiction series of the Glahangari series.

This book is the fourth work in Peter Hessler's so-called 'Chinese Trilogy', following 'Rivertown', 'Oracle Bone Script', and 'Country Driving'.

In this book, Hessler, a renowned nonfiction writer specializing in China, depicts the lives of several generations of Chinese people amidst the maelstrom of tremendous social, political, and economic transformation with deep compassion, humor, and seriousness.

From 2020 to 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hessler taught nonfiction to students at Sichuan University in Chongqing. He also became a parent with his wife, helping his two children enroll and adjust to local elementary schools.

The author, who could be said to have experienced China quite a bit, had no choice but to experience this vast society, which had become completely new and irregular in the pandemic situation, from a new perspective and sense, and he created another human documentary by mixing various situations that were sometimes serious and sometimes laughable.

Pamela Druckerman said of the book, “This book paints a portrait of modern China, full of witty observations and deep empathy, drawing on the lives of the Chinese students she taught and the experiences of her own daughters in local schools.

Hessler, who believes that the true story of China is revealed through microsavages, everyday conversations, and the joy of glimpses into everyday life, avoids jumping to conclusions.

“This book is journalism in its most human form, and (especially for readers like us who are not Sinologists) it is the perfect introduction to what the real China is like,” he commented.

What kind of world will they create in the future?

The reality faced by two generations of young people in China from 1996 to the present

The most human journalism, portrayed with deep empathy and sincerity.

I said that I think young people are risk-averse because they are only children who feel pressured to succeed.

They also said that they were much better educated and more aware of the outside world than previous generations.

“But I don’t know what this means for the future,” I said.

“Maybe they will figure out a way to change the system.

But maybe we just figure out how to adapt to the system.”

I looked at the young faces surrounding me and asked:

“What do you think?”

“We’ll adapt,” one girl said, and several nodded.

“It’s easy to get angry, but it’s easy to forget anger,” said another student.

But Serena, who was sitting at the back of the group, said this.

“We will change the system.”

_From page 522 of the text

Peter Hessler's 2024 new book, Portrait of a Young People (original title: Other Rivers), has been translated and published as the 29th book in the Masterpiece Nonfiction series of the Glahangari series.

This book is the fourth work in Peter Hessler's so-called 'Chinese Trilogy', following 'Rivertown', 'Oracle Bone Script', and 'Country Driving'.

In this book, Hessler, a renowned nonfiction writer specializing in China, depicts the lives of several generations of Chinese people amidst the maelstrom of tremendous social, political, and economic transformation with deep compassion, humor, and seriousness.

From 2020 to 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hessler taught nonfiction to students at Sichuan University in Chongqing. He also became a parent with his wife, helping his two children enroll and adjust to local elementary schools.

The author, who could be said to have experienced China quite a bit, had no choice but to experience this vast society, which had become completely new and irregular in the pandemic situation, from a new perspective and sense, and he created another human documentary by mixing various situations that were sometimes serious and sometimes laughable.

Pamela Druckerman said of the book, “This book paints a portrait of modern China, full of witty observations and deep empathy, drawing on the lives of the Chinese students she taught and the experiences of her own daughters in local schools.

Hessler, who believes that the true story of China is revealed through microsavages, everyday conversations, and the joy of glimpses into everyday life, avoids jumping to conclusions.

“This book is journalism in its most human form, and (especially for readers like us who are not Sinologists) it is the perfect introduction to what the real China is like,” he commented.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Part 1

Chapter 1: Rejection

Chapter 2 Old Campus

Chapter 3 New Campus

Chapter 4 Chengdu Experimental School

Chapter 5 Earthquake

Part 2

Chapter 6: The City That Fell

Chapter 7: Children of Corona

Chapter 8: The Blockaded City

Chapter 9: Neijuan

Chapter 10: Common Sense

Chapter 11: The Xi Jinping Generation

Backstory: Uncompahgre River

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

Chapter 1: Rejection

Chapter 2 Old Campus

Chapter 3 New Campus

Chapter 4 Chengdu Experimental School

Chapter 5 Earthquake

Part 2

Chapter 6: The City That Fell

Chapter 7: Children of Corona

Chapter 8: The Blockaded City

Chapter 9: Neijuan

Chapter 10: Common Sense

Chapter 11: The Xi Jinping Generation

Backstory: Uncompahgre River

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

Into the book

He explained that the Chinese government's authoritarianism creates two dynamics.

While local officials tend to cover things up, senior leaders are equipped to respond quickly and effectively.

Zhang's view was that China would fail in the early stages of the crisis and only improve in the later stages.

--- p.384

Of course, all of this was just speculation.

No one could truly understand the US-China relationship or the strange way ideas and products flowed between the two countries.

Some Chinese students come to class wearing Trump hats to commemorate the US president's connection to Sichuan, while others use the title of a Thomas Paine pamphlet in their underground publications.

A manufacturer in Zhejiang Province could turn a Boy Pioneer scarf into a Trump flag, and a businessman in Chengdu could use a fierce commercial "exchange" to determine the exact date when American consumers will receive their stimulus checks.

But all these little touches didn't lead to the big picture of empathy and understanding.

--- p.477

Most of my former students living abroad had plans to return to China someday.

But a few told me they wanted to settle in the US or Europe, which seemed to be part of a larger trend.

Young people called it Runxue, meaning "the study of escape." (A neologism derived from the fact that the alphabet of Run, meaning "affluent life," is the same as the English word "run.") There were signs that some young Chinese people, especially those with higher education, were considering emigrating.

--- p.558

It was very depressing and scary to realize that there was nowhere inside the Great Firewall where we could safely talk.

They are looking at all our information.

We stopped working, and Common Sense hasn't published any articles since.

I even began to doubt the meaning of writing.

“If I can’t publish my writing and people can’t read it, what good does it do to me?”

--- p.560

When I was in Sichuan, I often found myself repeating the same mantra.

Nothing has changed, yet everything has changed.

On one side is the perspective of a foreigner.

The Chinese have driven so many changes in society, economy, and education, so why can't they do the same in politics? But the other side of the argument is equally compelling.

Many Chinese, especially those in the provinces, believed that political stability was necessary for all these changes.

While local officials tend to cover things up, senior leaders are equipped to respond quickly and effectively.

Zhang's view was that China would fail in the early stages of the crisis and only improve in the later stages.

--- p.384

Of course, all of this was just speculation.

No one could truly understand the US-China relationship or the strange way ideas and products flowed between the two countries.

Some Chinese students come to class wearing Trump hats to commemorate the US president's connection to Sichuan, while others use the title of a Thomas Paine pamphlet in their underground publications.

A manufacturer in Zhejiang Province could turn a Boy Pioneer scarf into a Trump flag, and a businessman in Chengdu could use a fierce commercial "exchange" to determine the exact date when American consumers will receive their stimulus checks.

But all these little touches didn't lead to the big picture of empathy and understanding.

--- p.477

Most of my former students living abroad had plans to return to China someday.

But a few told me they wanted to settle in the US or Europe, which seemed to be part of a larger trend.

Young people called it Runxue, meaning "the study of escape." (A neologism derived from the fact that the alphabet of Run, meaning "affluent life," is the same as the English word "run.") There were signs that some young Chinese people, especially those with higher education, were considering emigrating.

--- p.558

It was very depressing and scary to realize that there was nowhere inside the Great Firewall where we could safely talk.

They are looking at all our information.

We stopped working, and Common Sense hasn't published any articles since.

I even began to doubt the meaning of writing.

“If I can’t publish my writing and people can’t read it, what good does it do to me?”

--- p.560

When I was in Sichuan, I often found myself repeating the same mantra.

Nothing has changed, yet everything has changed.

On one side is the perspective of a foreigner.

The Chinese have driven so many changes in society, economy, and education, so why can't they do the same in politics? But the other side of the argument is equally compelling.

Many Chinese, especially those in the provinces, believed that political stability was necessary for all these changes.

--- p.561

Publisher's Review

Peter Hessler's 2024 new book, Portrait of a Young People (original title: Other Rivers), has been translated and published as the 29th book in the Masterpiece Nonfiction series of the Glahangari series.

This book is the fourth work in Peter Hessler's so-called 'Chinese Trilogy', following 'Rivertown', 'Oracle Bone Script', and 'Country Driving'.

In this book, Hessler, a renowned nonfiction writer specializing in China, depicts the lives of several generations of Chinese people amidst the maelstrom of tremendous social, political, and economic transformation with deep compassion, humor, and seriousness.

From 2020 to 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hessler taught nonfiction to students at Sichuan University in Chongqing. He also became a parent with his wife, helping his two children enroll and adjust to local elementary schools.

The author, who could be said to have experienced China quite a bit, had no choice but to experience this vast society, which had become completely new and irregular in the pandemic situation, from a new perspective and sense, and he created another human documentary by mixing various situations that were sometimes serious and sometimes laughable.

Pamela Druckerman said of the book, “This book paints a portrait of modern China, full of witty observations and deep empathy, drawing on the lives of the Chinese students she taught and the experiences of her own daughters in local schools.

Hessler, who believes that the true story of China is revealed through microsavages, everyday conversations, and the joy of glimpses into everyday life, avoids jumping to conclusions.

“This book is journalism in its most human form, and (especially for readers like us who are not Sinologists) it is the perfect introduction to what the real China is like,” he commented.

As such, Peter Hessler is an author with a hidden fan base, as almost all of his works have been continuously introduced to Korean society.

In the afterword, co-translators Park Kyung-hwan and Yoon Young-soo, who translated this new book, describe in detail their first meeting with the author Hessler and provide a glimpse into his writing career.

The translators were in China around 2008.

As I was entering my seventh year of living in China, I was slowly losing my mind and body due to the accumulated stress of living abroad. Then, I read “Rivertown” and found salvation.

In the 2000s, when the fervor of reform and opening up that began in 1978 reached its peak, there was an atmosphere in China that, looking back, was reminiscent of the American Wild West.

China's accession to the WTO brought with it a surge of anticipation for all sorts of business opportunities, a surge of real estate development that transformed city skylines by the month, and a flurry of Chinese companies going overseas for spectacular IPOs.

But this rapid material growth inevitably left behind some absurdities.

Institutions failed to keep up with reality, the ends justified the means, and it was common for material wealth to lead to a loss of consideration for others.

Translators believe that much of our negative preconceptions about China stem from this period of contact.

While foreigners living in China enjoyed the fruits of economic growth, they were busy stereotyping Chinese people, making fun of them and making fun of them.

I wasn't free there either, and that kind of life couldn't be healthy.

It was around the time that accumulated stress was finally manifesting itself as health problems that I came across Hessler's first book, Rivertown.

Peter Hessler's experiences and perspectives were fresh from his two years at a small Sichuan Normal University as a member of the U.S. Peace Corps in the 1990s.

The human relationships he formed were not short-term relationships based on profit, but rather long-term relationships between teachers and students and colleagues.

It was amazing to see a young foreigner with virtually no understanding of China learn the language and become immersed in the local life.

That doesn't mean he beautified his surroundings.

His surroundings, like mine, were filled with all kinds of absurdities.

However, he only tried to be affectionate and understanding to those around him.

Some media outlets have called this attitude of Peter Hessler “informed empathy.”

Just realizing that coexistence begins with understanding the other person's perspective—this simple yet difficult-to-practice attitude—gave me immense comfort and helped me escape the mental trap I had created.

After completing his service in the Peace Corps, Peter Hessler returned to China as a journalist and stayed there for about eight years, writing his follow-up works, “Oracle Bone Script” and “Country Driving.”

These two books are filled with the life stories of dozens of students I taught at Chongqing Normal University and their lives after graduation.

I had been exchanging greetings with my disciples through letters and emails.

Unlike other correspondents, Peter Hessler develops deep relationships with his sources over many years.

Rather than finding a macro item and finding a source that fits that, by getting to know the sources for a long time, the macro environment of China in which they live is naturally revealed.

After that, he spent several years as a correspondent in Egypt via the United States and then returned to China.

In 2019, I was hired officially at Sichuan University in the metropolis of Chengdu to teach nonfiction writing.

The students are the children of students I taught in the 1990s.

The main theme of this book is to compare two generations: the generation that grew up with reform and opening up, and the younger generation that spent their teenage years after Xi Jinping came to power, through the unwaveringly bright eyes of Peter Hessler.

As longtime readers of Rivertown, the translators say they were moved by the scenes in which the author reunites with his former students, now in their late 40s, and continues their relationship.

There are several other strands in the book, one of which is the author's story of sending her twin elementary school-aged daughters to a local school in China.

He details the process of his daughters, who could not speak a word of Chinese, adapting to Chinese school, and thinks about the pros and cons of Chinese education.

And in the meantime, COVID-19 breaks out.

At a time when most American correspondents were expelled due to the worsening US-China relationship, Peter Hessler, a former teacher, took on the role of a journalist and conducted extensive reporting, including a visit to Wuhan.

Perhaps because of that, he was denied renewal of his contract at the university for no clear reason, and ended his life in China after two years, earlier than planned.

This book is a record of those two years.

Coincidentally, it has a form that corresponds to 『Rivertown』, which was a two-year record in the 1990s.

Peter Hessler is also a master of 'show not tell'.

I learned writing directly from John McPhee, a master of nonfiction who is famous for showing between the lines, during my college years.

The translators had the opportunity to examine how he had revised the text twice after completing the translation of this book.

By removing unnecessary sentences, adjusting the rhythm of paragraphs, and eliminating direct adjectives and adverbs, I could vaguely catch a glimpse of his skill in conveying emotions and thoughts more completely by not forcing them on the reader.

This type of writing can easily become overly reliant on emotional resonance, but Peter Hessler balances it out with a journalist's meticulousness.

Investigate the socio-cultural background surrounding the phenomenon to provide context, cross-check facts, and give meaning, but do not generalize hastily.

The attitude of being meticulous in caring for sources also stands out.

This book is the fourth work in Peter Hessler's so-called 'Chinese Trilogy', following 'Rivertown', 'Oracle Bone Script', and 'Country Driving'.

In this book, Hessler, a renowned nonfiction writer specializing in China, depicts the lives of several generations of Chinese people amidst the maelstrom of tremendous social, political, and economic transformation with deep compassion, humor, and seriousness.

From 2020 to 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hessler taught nonfiction to students at Sichuan University in Chongqing. He also became a parent with his wife, helping his two children enroll and adjust to local elementary schools.

The author, who could be said to have experienced China quite a bit, had no choice but to experience this vast society, which had become completely new and irregular in the pandemic situation, from a new perspective and sense, and he created another human documentary by mixing various situations that were sometimes serious and sometimes laughable.

Pamela Druckerman said of the book, “This book paints a portrait of modern China, full of witty observations and deep empathy, drawing on the lives of the Chinese students she taught and the experiences of her own daughters in local schools.

Hessler, who believes that the true story of China is revealed through microsavages, everyday conversations, and the joy of glimpses into everyday life, avoids jumping to conclusions.

“This book is journalism in its most human form, and (especially for readers like us who are not Sinologists) it is the perfect introduction to what the real China is like,” he commented.

As such, Peter Hessler is an author with a hidden fan base, as almost all of his works have been continuously introduced to Korean society.

In the afterword, co-translators Park Kyung-hwan and Yoon Young-soo, who translated this new book, describe in detail their first meeting with the author Hessler and provide a glimpse into his writing career.

The translators were in China around 2008.

As I was entering my seventh year of living in China, I was slowly losing my mind and body due to the accumulated stress of living abroad. Then, I read “Rivertown” and found salvation.

In the 2000s, when the fervor of reform and opening up that began in 1978 reached its peak, there was an atmosphere in China that, looking back, was reminiscent of the American Wild West.

China's accession to the WTO brought with it a surge of anticipation for all sorts of business opportunities, a surge of real estate development that transformed city skylines by the month, and a flurry of Chinese companies going overseas for spectacular IPOs.

But this rapid material growth inevitably left behind some absurdities.

Institutions failed to keep up with reality, the ends justified the means, and it was common for material wealth to lead to a loss of consideration for others.

Translators believe that much of our negative preconceptions about China stem from this period of contact.

While foreigners living in China enjoyed the fruits of economic growth, they were busy stereotyping Chinese people, making fun of them and making fun of them.

I wasn't free there either, and that kind of life couldn't be healthy.

It was around the time that accumulated stress was finally manifesting itself as health problems that I came across Hessler's first book, Rivertown.

Peter Hessler's experiences and perspectives were fresh from his two years at a small Sichuan Normal University as a member of the U.S. Peace Corps in the 1990s.

The human relationships he formed were not short-term relationships based on profit, but rather long-term relationships between teachers and students and colleagues.

It was amazing to see a young foreigner with virtually no understanding of China learn the language and become immersed in the local life.

That doesn't mean he beautified his surroundings.

His surroundings, like mine, were filled with all kinds of absurdities.

However, he only tried to be affectionate and understanding to those around him.

Some media outlets have called this attitude of Peter Hessler “informed empathy.”

Just realizing that coexistence begins with understanding the other person's perspective—this simple yet difficult-to-practice attitude—gave me immense comfort and helped me escape the mental trap I had created.

After completing his service in the Peace Corps, Peter Hessler returned to China as a journalist and stayed there for about eight years, writing his follow-up works, “Oracle Bone Script” and “Country Driving.”

These two books are filled with the life stories of dozens of students I taught at Chongqing Normal University and their lives after graduation.

I had been exchanging greetings with my disciples through letters and emails.

Unlike other correspondents, Peter Hessler develops deep relationships with his sources over many years.

Rather than finding a macro item and finding a source that fits that, by getting to know the sources for a long time, the macro environment of China in which they live is naturally revealed.

After that, he spent several years as a correspondent in Egypt via the United States and then returned to China.

In 2019, I was hired officially at Sichuan University in the metropolis of Chengdu to teach nonfiction writing.

The students are the children of students I taught in the 1990s.

The main theme of this book is to compare two generations: the generation that grew up with reform and opening up, and the younger generation that spent their teenage years after Xi Jinping came to power, through the unwaveringly bright eyes of Peter Hessler.

As longtime readers of Rivertown, the translators say they were moved by the scenes in which the author reunites with his former students, now in their late 40s, and continues their relationship.

There are several other strands in the book, one of which is the author's story of sending her twin elementary school-aged daughters to a local school in China.

He details the process of his daughters, who could not speak a word of Chinese, adapting to Chinese school, and thinks about the pros and cons of Chinese education.

And in the meantime, COVID-19 breaks out.

At a time when most American correspondents were expelled due to the worsening US-China relationship, Peter Hessler, a former teacher, took on the role of a journalist and conducted extensive reporting, including a visit to Wuhan.

Perhaps because of that, he was denied renewal of his contract at the university for no clear reason, and ended his life in China after two years, earlier than planned.

This book is a record of those two years.

Coincidentally, it has a form that corresponds to 『Rivertown』, which was a two-year record in the 1990s.

Peter Hessler is also a master of 'show not tell'.

I learned writing directly from John McPhee, a master of nonfiction who is famous for showing between the lines, during my college years.

The translators had the opportunity to examine how he had revised the text twice after completing the translation of this book.

By removing unnecessary sentences, adjusting the rhythm of paragraphs, and eliminating direct adjectives and adverbs, I could vaguely catch a glimpse of his skill in conveying emotions and thoughts more completely by not forcing them on the reader.

This type of writing can easily become overly reliant on emotional resonance, but Peter Hessler balances it out with a journalist's meticulousness.

Investigate the socio-cultural background surrounding the phenomenon to provide context, cross-check facts, and give meaning, but do not generalize hastily.

The attitude of being meticulous in caring for sources also stands out.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 12, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 616 pages | 756g | 141*205*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791169093156

- ISBN10: 1169093159

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)