There was a Korean on the Bridge on the River Kwai

|

Description

Book Introduction

This book, which is set primarily in the colonial imperial period from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, “a time when worlds that had been divided for a long time became deeply intertwined” and “the most recent past that shaped the world we live in now,” is a liberal arts history book that crosses the continents, horizontally connecting contemporary figures interacting with each other, and vertically traversing the legacy of the time’s thought systems, perceptions, and sensibilities that continue to this day.

In the midst of the turbulent history that continues from the Paris Commune, Russo-Japanese War, Boxer Rebellion, World War I, March 1st Movement, First Shanghai Incident, Berlin Olympics, Second Sino-Japanese War, and World War II, politicians and soldiers, entertainers and writers, scientists and intellectuals, women who sell sex and women's rights activists, independence activists and spies, and ordinary people appear.

Many of the novels, movies, and songs they enjoyed are also cited.

All of these things unfold like a drama, a story of “being caught up in history, making history, and eventually becoming history.”

This book, which understands the essence of history as connection and involvement, focuses on the minds and attitudes of individuals as they move and react, rather than the familiar historical narratives of nations and ethnic groups, summarized as good and evil, victory and defeat, harm and harm.

It portrays the dynamics of characters who love, make mistakes, dream, and desire, meeting, becoming entangled with each other, and giving and receiving.

In the process, we examine the historical responsibility they must bear, the responsibility history must bear to them, and further, the responsibility we, as involved parties, must bear now.

In the midst of the turbulent history that continues from the Paris Commune, Russo-Japanese War, Boxer Rebellion, World War I, March 1st Movement, First Shanghai Incident, Berlin Olympics, Second Sino-Japanese War, and World War II, politicians and soldiers, entertainers and writers, scientists and intellectuals, women who sell sex and women's rights activists, independence activists and spies, and ordinary people appear.

Many of the novels, movies, and songs they enjoyed are also cited.

All of these things unfold like a drama, a story of “being caught up in history, making history, and eventually becoming history.”

This book, which understands the essence of history as connection and involvement, focuses on the minds and attitudes of individuals as they move and react, rather than the familiar historical narratives of nations and ethnic groups, summarized as good and evil, victory and defeat, harm and harm.

It portrays the dynamics of characters who love, make mistakes, dream, and desire, meeting, becoming entangled with each other, and giving and receiving.

In the process, we examine the historical responsibility they must bear, the responsibility history must bear to them, and further, the responsibility we, as involved parties, must bear now.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

1.

Thinking of Li Xianglan in the face of historical regression

2.

Your Name, forgetting by remembering

3.

There was a Korean on the Bridge on the River Kwai

4.

Beyond the narrative of self-pity: homesickness in the Casbah

5.

The story of a Westerner who hated Koreans

6.

Dream of traveling around the world, meet me when you return

7.

Do you know Elena?

8.

When Western gaze portrays Eastern women

9.

Will science save us?

10.

Doctors who crossed the Yalu River

11.

A community in disaster, beyond indifference and sympathy

12.

Are stars born in colonies too?

13.

Sakhalin Koreans, where is my country?

14.

Duet of Revolution and Love

15.

Leni Riefenstahl: Is Ignorant Beauty Innocent?

16.

How does a little person grow up?

17.

The Unheard Story Beyond The Sound of Music

18.

I walked without stars on the dark colonial night

main

1.

Thinking of Li Xianglan in the face of historical regression

2.

Your Name, forgetting by remembering

3.

There was a Korean on the Bridge on the River Kwai

4.

Beyond the narrative of self-pity: homesickness in the Casbah

5.

The story of a Westerner who hated Koreans

6.

Dream of traveling around the world, meet me when you return

7.

Do you know Elena?

8.

When Western gaze portrays Eastern women

9.

Will science save us?

10.

Doctors who crossed the Yalu River

11.

A community in disaster, beyond indifference and sympathy

12.

Are stars born in colonies too?

13.

Sakhalin Koreans, where is my country?

14.

Duet of Revolution and Love

15.

Leni Riefenstahl: Is Ignorant Beauty Innocent?

16.

How does a little person grow up?

17.

The Unheard Story Beyond The Sound of Music

18.

I walked without stars on the dark colonial night

main

Detailed image

Into the book

The true history of 'The Bridge on the River Kwai' asks us to reconsider our conventional perceptions of history.

What kind of perception is this? It's the perception that history flows through nations and ethnic groups, and that there are clear perpetrators and victims.

Real history often crosses boundaries, creates boundaries, and changes them.

The actual history of the Bridge on the River Kwai is also a 'disjointed common history' involving Britain, Japan, Korea, Thailand, and Myanmar.

--- p.9~10

Li Xianglan, a Japanese national who was popular on the Korean Peninsula under the name of Lee Hyangran, became deeply involved in the comfort women issue in the 1990s.

How should we view her apology? The scene of Son Ki-chung winning the marathon, which almost every Korean has seen, is a highlight of Riefenstahl's masterpiece, [Olympia].

Riefenstahl, who had been criticized for her Nazi ties, regained fame by capturing the disappearing indigenous people of Africa in her photographs.

How should we interpret her fame? Marlene Dietrich, Riefenstahl's rival in Germany, rose through the Hollywood star system and became a global darling, including in Korea, on the big screen.

She was the original 'Shanghai Lil', a Western man's fantasy of Eastern women, and fought against the Nazis.

What kind of person is she?

--- p.10~11

What kind of people were the prison guards? They were always under surveillance to make sure they were keeping a good watch.

I always got hit because I was told to hit hard.

Pierre Boulle writes in The Bridge on the River Kwai:

“Colonel Nicholson was beaten again, and the gorilla-like Korean was ordered to resume the harsh regime of the first few days.

Saito even hit the guard.

He threatened to use his pistol not only on the prisoners but also on the guards.” They were both the perpetrator and the victim.

He was a victim of overlapping fates.

Aiko Utsumi, a Japanese sociologist who studied the tragedy of Korean Class B and C war criminals, says that while there was some personal abuse by prison guards, the very situation in which they had no choice but to abuse prisoners due to lack of food and medicine should be addressed.

--- p.60~61

The Korean prisoner-of-war guards were perpetrators who collaborated with the Japanese in their war efforts.

Based on these cases, some people claim that Korea, like Japan, is a war criminal nation.

The practical implication is that Japan cannot be held responsible for the war, as it is a fellow war criminal country that sided with Japan.

It is just one of the arguments that agree with the logic of denying responsibility for the war.

On the other hand, there is the idea that they were simply victims, having been taken by force.

If there is structural evil, can the ethical responsibility of individuals who participate in it be simply absolved? As Lee Hak-rae confesses in his memoir, that's not the case.

We must recognize our share of historical responsibility without identifying with Japan.

Only then can one become an ethical subject.

--- p.62~63

There is also a much more trivial story.

In his memoirs, British prisoner Urquhart recalls the harrowing experience of being transported on a train like a piece of luggage, in fear of suffocation.

One day, while being transported, the prisoners begged the Korean guards not to close the door, saying that they would not escape and that they would close the door when they arrived.

Surprisingly, he didn't close the door.

“A pleasant breeze blew as we moved.

…I could never forget that the guards had allowed me to leave the door open, nor could I forget the first kindness and sympathy I received from one of them.”

No one escaped.

Rather than escaping, he repaid the kindness of the Korean prisoner guards by closing the door upon arrival, thus avoiding suspicion.

There were those who risked their lives to do small favors.

One wonders what meaning such a small favor can have in the face of such a terrible tragedy.

However, Aquatt remembered this and recorded it.

So we found out.

Could hope perhaps be found here?

--- p.65~66

Yun Chi-ho (1865-1945) also accepted social Darwinism while studying in the United States.

After experiencing racial discrimination, they come to accept the social Darwinism argument that 'might makes right'.

Of course, Yun Chi-ho was a more complex person than Yu Gil-jun.

He was particularly troubled by the dissonance between Christian faith and social Darwinism.

In his diary from one day in 1892, he agonizes:

“The greatest obstacle to my faith and belief is racial inequality and the many harms it causes.

Why didn't God grant equal opportunity and equal physical and mental abilities to Caucasians, Mongolians, Africans, and others? … Couldn't God have done so, even though He wanted to? What then is His wisdom? Couldn't He have done so, yet deliberately avoided it? What then is His love? Oh, the riddle!

--- p.93

The reality that Lee Soon-tak encountered upon returning from his world tour was different from the reality that Na Hye-seok and Park In-deok encountered upon returning.

For the intellectual elite male, traveling the world was not a life-changing adventure.

However, that doesn't mean the reality was rosy.

In April 1938, Lee Soon-tak was arrested along with professors Baek Nam-un and No Dong-gyu of the same department and students, accused of being the mastermind behind the 'Yeonhui College Economic Research Society Incident'.

He was sentenced to prison and served his sentence until July 1940.

Even after being released from prison, he was unable to return to work.

However, thanks to the school's consideration, he served as the head of the accounting department at Severance Hospital until liberation.

After the government was established, he participated as the first director of the planning department and worked hard to prepare a land reform plan.

There are clear traces of contributions from centrist leftists, such as Minister of Agriculture and Forestry Cho Bong-am and Director of Planning Lee Soon-tak, in South Korea's land reform.

He was abducted during the Korean War and his life or death was unknown until he was later found dead in October 1950.

--- p.114~115

Just as the hierarchy of power and cultural imagination between Korea, Japan, and the United States was stark, so too was the hierarchy of sexual fantasies.

While men from victorious nations dreamed of casual romances with women from conquered lands, men from defeated, weak nations trembled with shame, regret, and sometimes even anger.

--- p.125

It was a period that British historian Eric Hobsbawm called the Age of Empire (1875-1914).

The expansionist competition among the great powers was evolving beyond the long-distance trade and resource plunder of the early colonial period to include large-scale migration and capital export.

Ideologies, cultural imaginations, and works that fuel and justify the West's desire for expansion have emerged one after another.

Only the West could have the authority to define and express the non-West, the Orient.

All the discourses, knowledge, and cultural representations that described and analyzed the Orient through Western eyes eventually transformed into a style that dominated, reconstructed, oppressed, and disciplined the Orient.

It was an era when Western cultural hegemony reached its peak, a period captured by Palestinian-born English literature scholar Edward Said under the name of 'Orientalism.'

[Madame Butterfly] can be said to be a typical example of an Orientalist cultural product.

--- p.134

When criticized for developing poison gas, Haber protested.

“In times of peace, a scientist belongs to the world, but in times of war, he belongs to his country.” He was so patriotic towards Germany that he risked the destruction of his family, but he had to go into exile when the Nazis came to power in 1933.

Because he was Jewish.

After traveling to several countries, he died in Switzerland the following year.

Zyklon B, an insecticide developed by Haber, was widely used in the massacre of Jews during World War II.

It was a horrific poison gas that did not kill instantly, but caused a slow and painful death.

Could he have imagined this tragedy? His eldest son, Hermann, fled to the United States via France, where he committed suicide in 1946.

Hermann's daughter Claire grew up in the United States as a chemist.

While he was working on developing an antidote to chlorine gas created by his grandfather, he committed suicide when he heard that the research budget was being prioritized for the development of nuclear bombs.

It was 1949.

It is unclear whether science saved the world.

It is clear that we failed to save the scientist who said he would save the world.

--- p.157~158

Lee Gwang-su's interest in science did not last long.

Instead, in the 1930s, he was immersed in totalitarian ideologies such as Nazism and fascism.

Excerpts from Hitler's Mein Kampf were translated in 1930, before the Nazis came to power.

It was he who coined and spread the word totalitarianism.

Although science has become totalitarian, there are still enduring interests within it.

It is the ‘worship of power.’

Let's look back.

In the final scene of "Heartless," what did he vow just before he cried out, "Science! Science!"? "I must give them strength.

I must impart knowledge.

So, we must secure the foundation of our lives.” It was not difficult for the yearning for a power that could help the world to change into a worship of a power that could rule the world.

--- p.161

Around 1936, while Marlene Dietrich was working in the United States and staying in London to film a movie, she was approached by the Nazis.

He requested to return to Germany with the promise of the best treatment.

In fact, Dietrich was Hitler's favorite actor.

She declined the offer and applied for U.S. citizenship in 1937.

In the same year, he donated $450,000 from his appearance fee for [The Knight Without Armor] to a fund to help Jews escape from Germany.

When the war broke out, he took the lead in selling national bonds to raise war funds, and traveled to battlefields to perform and visit hospitals.

While Riefenstahl made films for the Nazis, Dietrich stood up to them.

After the war, he was condemned as a traitor in Germany.

He was unable to reconcile with Germany during his lifetime.

He left a will asking to be buried in Paris, not in Germany or the United States.

In 2002, ten years after Dietrich's death, the German government posthumously made her an honorary citizen of Germany and named a square in her hometown after her.

The cemetery in Paris was also moved.

What kind of perception is this? It's the perception that history flows through nations and ethnic groups, and that there are clear perpetrators and victims.

Real history often crosses boundaries, creates boundaries, and changes them.

The actual history of the Bridge on the River Kwai is also a 'disjointed common history' involving Britain, Japan, Korea, Thailand, and Myanmar.

--- p.9~10

Li Xianglan, a Japanese national who was popular on the Korean Peninsula under the name of Lee Hyangran, became deeply involved in the comfort women issue in the 1990s.

How should we view her apology? The scene of Son Ki-chung winning the marathon, which almost every Korean has seen, is a highlight of Riefenstahl's masterpiece, [Olympia].

Riefenstahl, who had been criticized for her Nazi ties, regained fame by capturing the disappearing indigenous people of Africa in her photographs.

How should we interpret her fame? Marlene Dietrich, Riefenstahl's rival in Germany, rose through the Hollywood star system and became a global darling, including in Korea, on the big screen.

She was the original 'Shanghai Lil', a Western man's fantasy of Eastern women, and fought against the Nazis.

What kind of person is she?

--- p.10~11

What kind of people were the prison guards? They were always under surveillance to make sure they were keeping a good watch.

I always got hit because I was told to hit hard.

Pierre Boulle writes in The Bridge on the River Kwai:

“Colonel Nicholson was beaten again, and the gorilla-like Korean was ordered to resume the harsh regime of the first few days.

Saito even hit the guard.

He threatened to use his pistol not only on the prisoners but also on the guards.” They were both the perpetrator and the victim.

He was a victim of overlapping fates.

Aiko Utsumi, a Japanese sociologist who studied the tragedy of Korean Class B and C war criminals, says that while there was some personal abuse by prison guards, the very situation in which they had no choice but to abuse prisoners due to lack of food and medicine should be addressed.

--- p.60~61

The Korean prisoner-of-war guards were perpetrators who collaborated with the Japanese in their war efforts.

Based on these cases, some people claim that Korea, like Japan, is a war criminal nation.

The practical implication is that Japan cannot be held responsible for the war, as it is a fellow war criminal country that sided with Japan.

It is just one of the arguments that agree with the logic of denying responsibility for the war.

On the other hand, there is the idea that they were simply victims, having been taken by force.

If there is structural evil, can the ethical responsibility of individuals who participate in it be simply absolved? As Lee Hak-rae confesses in his memoir, that's not the case.

We must recognize our share of historical responsibility without identifying with Japan.

Only then can one become an ethical subject.

--- p.62~63

There is also a much more trivial story.

In his memoirs, British prisoner Urquhart recalls the harrowing experience of being transported on a train like a piece of luggage, in fear of suffocation.

One day, while being transported, the prisoners begged the Korean guards not to close the door, saying that they would not escape and that they would close the door when they arrived.

Surprisingly, he didn't close the door.

“A pleasant breeze blew as we moved.

…I could never forget that the guards had allowed me to leave the door open, nor could I forget the first kindness and sympathy I received from one of them.”

No one escaped.

Rather than escaping, he repaid the kindness of the Korean prisoner guards by closing the door upon arrival, thus avoiding suspicion.

There were those who risked their lives to do small favors.

One wonders what meaning such a small favor can have in the face of such a terrible tragedy.

However, Aquatt remembered this and recorded it.

So we found out.

Could hope perhaps be found here?

--- p.65~66

Yun Chi-ho (1865-1945) also accepted social Darwinism while studying in the United States.

After experiencing racial discrimination, they come to accept the social Darwinism argument that 'might makes right'.

Of course, Yun Chi-ho was a more complex person than Yu Gil-jun.

He was particularly troubled by the dissonance between Christian faith and social Darwinism.

In his diary from one day in 1892, he agonizes:

“The greatest obstacle to my faith and belief is racial inequality and the many harms it causes.

Why didn't God grant equal opportunity and equal physical and mental abilities to Caucasians, Mongolians, Africans, and others? … Couldn't God have done so, even though He wanted to? What then is His wisdom? Couldn't He have done so, yet deliberately avoided it? What then is His love? Oh, the riddle!

--- p.93

The reality that Lee Soon-tak encountered upon returning from his world tour was different from the reality that Na Hye-seok and Park In-deok encountered upon returning.

For the intellectual elite male, traveling the world was not a life-changing adventure.

However, that doesn't mean the reality was rosy.

In April 1938, Lee Soon-tak was arrested along with professors Baek Nam-un and No Dong-gyu of the same department and students, accused of being the mastermind behind the 'Yeonhui College Economic Research Society Incident'.

He was sentenced to prison and served his sentence until July 1940.

Even after being released from prison, he was unable to return to work.

However, thanks to the school's consideration, he served as the head of the accounting department at Severance Hospital until liberation.

After the government was established, he participated as the first director of the planning department and worked hard to prepare a land reform plan.

There are clear traces of contributions from centrist leftists, such as Minister of Agriculture and Forestry Cho Bong-am and Director of Planning Lee Soon-tak, in South Korea's land reform.

He was abducted during the Korean War and his life or death was unknown until he was later found dead in October 1950.

--- p.114~115

Just as the hierarchy of power and cultural imagination between Korea, Japan, and the United States was stark, so too was the hierarchy of sexual fantasies.

While men from victorious nations dreamed of casual romances with women from conquered lands, men from defeated, weak nations trembled with shame, regret, and sometimes even anger.

--- p.125

It was a period that British historian Eric Hobsbawm called the Age of Empire (1875-1914).

The expansionist competition among the great powers was evolving beyond the long-distance trade and resource plunder of the early colonial period to include large-scale migration and capital export.

Ideologies, cultural imaginations, and works that fuel and justify the West's desire for expansion have emerged one after another.

Only the West could have the authority to define and express the non-West, the Orient.

All the discourses, knowledge, and cultural representations that described and analyzed the Orient through Western eyes eventually transformed into a style that dominated, reconstructed, oppressed, and disciplined the Orient.

It was an era when Western cultural hegemony reached its peak, a period captured by Palestinian-born English literature scholar Edward Said under the name of 'Orientalism.'

[Madame Butterfly] can be said to be a typical example of an Orientalist cultural product.

--- p.134

When criticized for developing poison gas, Haber protested.

“In times of peace, a scientist belongs to the world, but in times of war, he belongs to his country.” He was so patriotic towards Germany that he risked the destruction of his family, but he had to go into exile when the Nazis came to power in 1933.

Because he was Jewish.

After traveling to several countries, he died in Switzerland the following year.

Zyklon B, an insecticide developed by Haber, was widely used in the massacre of Jews during World War II.

It was a horrific poison gas that did not kill instantly, but caused a slow and painful death.

Could he have imagined this tragedy? His eldest son, Hermann, fled to the United States via France, where he committed suicide in 1946.

Hermann's daughter Claire grew up in the United States as a chemist.

While he was working on developing an antidote to chlorine gas created by his grandfather, he committed suicide when he heard that the research budget was being prioritized for the development of nuclear bombs.

It was 1949.

It is unclear whether science saved the world.

It is clear that we failed to save the scientist who said he would save the world.

--- p.157~158

Lee Gwang-su's interest in science did not last long.

Instead, in the 1930s, he was immersed in totalitarian ideologies such as Nazism and fascism.

Excerpts from Hitler's Mein Kampf were translated in 1930, before the Nazis came to power.

It was he who coined and spread the word totalitarianism.

Although science has become totalitarian, there are still enduring interests within it.

It is the ‘worship of power.’

Let's look back.

In the final scene of "Heartless," what did he vow just before he cried out, "Science! Science!"? "I must give them strength.

I must impart knowledge.

So, we must secure the foundation of our lives.” It was not difficult for the yearning for a power that could help the world to change into a worship of a power that could rule the world.

--- p.161

Around 1936, while Marlene Dietrich was working in the United States and staying in London to film a movie, she was approached by the Nazis.

He requested to return to Germany with the promise of the best treatment.

In fact, Dietrich was Hitler's favorite actor.

She declined the offer and applied for U.S. citizenship in 1937.

In the same year, he donated $450,000 from his appearance fee for [The Knight Without Armor] to a fund to help Jews escape from Germany.

When the war broke out, he took the lead in selling national bonds to raise war funds, and traveled to battlefields to perform and visit hospitals.

While Riefenstahl made films for the Nazis, Dietrich stood up to them.

After the war, he was condemned as a traitor in Germany.

He was unable to reconcile with Germany during his lifetime.

He left a will asking to be buried in Paris, not in Germany or the United States.

In 2002, ten years after Dietrich's death, the German government posthumously made her an honorary citizen of Germany and named a square in her hometown after her.

The cemetery in Paris was also moved.

--- p.253~254

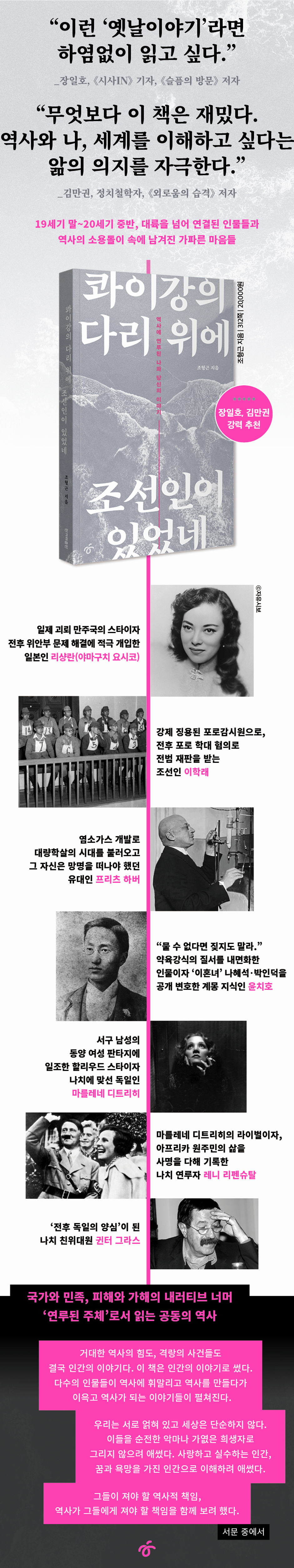

Publisher's Review

"I'd love to read these 'old tales' over and over again." _Jang Il-ho (Reporter for Sisa IN, Author of A Visit from Sadness)

“Above all, this book is fun.

“It stimulates the will to know, to understand history, myself, and the world.” _Kim Man-kwon (political philosopher, author of “Attack of Loneliness”)

Li Xianglan and Choi Seunghee, Hitler and Son Kee-chung, Ahn Chang-ho and Fanon,

Jack London and Yun Chi-ho, Na Hye-seok and Einstein…

From the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, people connected across continents

Steep hearts left behind in the whirlpool of history

This book, which is set primarily in the colonial and imperialist period from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, “a time when worlds that had been divided for a long time became deeply intertwined” and “the most recent past that shaped the world we live in now,” is a liberal arts history that crosses the continents, horizontally connecting contemporary figures interacting with each other, and vertically traversing the legacy of the time’s thought systems, perceptions, and sensibilities that have continued to the present.

In the midst of the turbulent history that continues from the Paris Commune, Russo-Japanese War, Boxer Rebellion, World War I, March 1st Movement, First Shanghai Incident, Berlin Olympics, Second Sino-Japanese War, and World War II, politicians and soldiers, entertainers and writers, scientists and intellectuals, women who sell sex and women's rights activists, independence activists and spies, and ordinary people appear.

Many of the novels, movies, and songs they enjoyed are also cited.

All of these things unfold like a drama, a story of “being caught up in history, making history, and eventually becoming history.”

This book is a compilation of 18 selected and supplemented articles from the series [Cho Hyung-geun's 'The Back Pages of History'] published in Sisa IN from May 2023 to August 2024.

This book, which focuses on recreating the complexities of individual hearts rather than major historical events, does not feature pure evil or pitiful victims.

However, it is full of three-dimensional figures of people who love, make mistakes, dream, and desire in the whirlwind of history, and the story that unfolds as they pass by and become intertwined with each other.

Choices, sometimes noble and sometimes vile, and the chain of events they bring about create and change history, crossing all the boundaries that constitute existing historical narratives: nation and people, good and evil, victory and defeat, harm and harm done.

The 'Bridge on the River Kwai' used in the title also shows a page of history that transcends boundaries.

In 1942, during the height of World War II, the Japanese army, which had occupied Southeast Asia, was looking beyond Burma (Myanmar) and even into India.

To this end, it was decided to build the Thailand-Burma Railway and forcibly mobilize Allied prisoners of war and local civilians.

Tens of thousands of people died in the difficult construction in rough terrain.

It is not well known that there were about 1,000 Koreans on that 'Death Railway'.

Those who were forcibly conscripted and worked as prisoner guards were beaten by the Japanese military, abused prisoners, and led the scene.

For some British prisoners of war, the most horrific sight of the perpetrator was also the face of a Korean.

After the war, they were subject to war crimes trials.

It is extremely unfair considering that they were drafted there and that many of their Japanese superiors were released without even being tried.

But does this mean there's no accountability for violence committed on orders? Above all, the parties involved didn't think so.

He visited the abused prisoners and apologized, while also holding the Japanese government accountable.

He was outraged by the violence he suffered and sought to take responsibility for the violence he committed.

They were not the only ones who became parties to overlapping destinies in the turbulent waves of history.

The story continues endlessly, revealing the diverse aspects of humanity that are difficult to capture with the logic of nation or race, good and evil, victim and perpetrator, and more: Japanese peace activist Li Xianglan (Yoshiko Yamaguchi), who became a star of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo while hiding her identity and actively intervened in resolving the comfort women issue after the war; Fritz Haber, a Jew who dramatically increased food production by developing nitrogen fertilizer and invented a method for producing chlorine gas, ushering in an era of mass slaughter; Yun Chi-ho, an enlightened intellectual who internalized the law of the jungle and publicly defended the divorced women Na Hye-seok and Park In-deok despite public criticism; Marlene Dietrich, a Hollywood star who contributed to Western men's fantasies about Asian women and a German who stood up to the Nazis; Leni Riefenstahl, a Nazi collaborator who dedicated herself to documenting the disappearing lives of indigenous Africans; and Gunter Grass, a Nazi SS member who became the "conscience of postwar Germany."

The great forces of history and the turbulent events are ultimately human stories.

This book was written as a human story.

Stories unfold of many characters becoming embroiled in history, making history, and eventually becoming history.

We are intertwined and the world is not simple.

I tried not to portray them as pure demons or pitiful victims.

I tried to understand them as human beings who love and make mistakes, as human beings with dreams and desires.

I tried to see together the historical responsibility they must bear and the responsibility history must bear them. (From the [Introduction])

Beyond indifference and sympathy

Reading a Common History as an 'Involved Subject'

When we talk about the imperialist period, we always take a clear position.

The facts of harm and harm are clearly distinguished, and the past is understood as a matter of demands rather than responsibility.

Acknowledging the damage and providing appropriate compensation is said to be the most appropriate way to overcome this period.

This book argues that a true break with this period is possible only when we move beyond the familiar perspective that sees the invasion of imperialist powers as the sole cause of the problem and use it as an opportunity for reflection to understand and reflect on the contemporary thought systems, perceptions, and sensibilities that made such violence possible.

For example, Chapter 9, 'Will Science Save Us?', examines the last scene of the novel 'Heartless', which interprets 'science' as 'power', Lee Kwang-soo's interest in Nazism and fascism, the Hwang Woo-suk boom and the superconductor controversy, and the life of Fritz Haber, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist who saved humanity from a food crisis and a Jew who opened the era of chemical warfare and mass genocide by developing chlorine gas. It makes us look back on the colonialism that still operates powerfully in a history that has reduced science only to power and competitiveness.

The history of sexual exploitation that emerged from Western men's fantasies about Oriental women, which blossomed in the Japanese concession of Shanghai, and the various cultural products that responded to them, and this Orientalist sensibility led to the "Pang Pang Girl" career women serving American soldiers in Japan, the "Elena" princess in South Korea, and the "Miss Saigon" in Vietnam, is also a theme that is repeatedly addressed throughout this book.

This makes us reflect on what "coming to terms with the past" means to those who have been mobilized and forgotten by the state, and how much we can alienate ourselves from this history in the present context.

Another important attempt of this book is to remind us that, as subjects of memory, we are always implicated in history.

A prime example is the way Korea and the United States remember the Vietnam War in public settings.

This is a selective memory that only commemorates and pities the veterans while omitting the Vietnamese victims, those who refused to be dragged into an immoral war and chose to go to prison, and anti-war activists, as well as the disparate responses to memorial services for Vietnam War veterans and the Japanese Prime Minister's visit to Yasukuni Shrine.

The author argues that our way of remembering war is intertwined with a reality where we express "national mourning" for repeated disasters, but fail to reflect on the structures that cause such tragedy.

This book shows that we can avoid repeating the past only when we thoroughly reflect on the historical responsibility we must bear, as well as the responsibility that history must bear to us, beyond indifference or sympathy. This also begins with deciding what to remember and how to remember it.

Looking back on the history of catastrophe

Flashes of light and attitude

Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist, said that everything can be taken from a human being but one thing: the freedom to choose and act in any given situation.

This book, which delicately follows the minds and attitudes of "ordinary people," is also a precious record that introduces a legacy of the mind, a flash of brilliance not recorded in capital-letter history, worthy of re-examination.

The granddaughter of Fritz Haber, the genius scientist who ushered in the era of chemical warfare and mass murder, devoted herself to developing an antidote to the poison gas her grandfather had created, but committed suicide when she heard that the research budget was being prioritized for the development of the atomic bomb. (p. 158) A British prisoner of war recalls the moment when, while being transported on a cargo ship bound for the River Kwai, a Korean guard opened the train door without his superiors knowing, as he was suffocating.

I remembered the pleasant breeze that blew then, the fact that no one escaped through the open door, and the sight of the prisoners quickly closing the door after arriving so as not to embarrass the guards. (Page 65) It is not a story that is remembered in official history, but someone remembered this moment for a long time and recorded it.

This book places these 'minor' choices on the stage of history and allows us to imagine other possibilities.

By looking back and remembering the small choices that transcended boundaries of ideology, nationality, and race and moved toward the "universal," wouldn't we perhaps have a very different history?

“Above all, this book is fun.

“It stimulates the will to know, to understand history, myself, and the world.” _Kim Man-kwon (political philosopher, author of “Attack of Loneliness”)

Li Xianglan and Choi Seunghee, Hitler and Son Kee-chung, Ahn Chang-ho and Fanon,

Jack London and Yun Chi-ho, Na Hye-seok and Einstein…

From the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, people connected across continents

Steep hearts left behind in the whirlpool of history

This book, which is set primarily in the colonial and imperialist period from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, “a time when worlds that had been divided for a long time became deeply intertwined” and “the most recent past that shaped the world we live in now,” is a liberal arts history that crosses the continents, horizontally connecting contemporary figures interacting with each other, and vertically traversing the legacy of the time’s thought systems, perceptions, and sensibilities that have continued to the present.

In the midst of the turbulent history that continues from the Paris Commune, Russo-Japanese War, Boxer Rebellion, World War I, March 1st Movement, First Shanghai Incident, Berlin Olympics, Second Sino-Japanese War, and World War II, politicians and soldiers, entertainers and writers, scientists and intellectuals, women who sell sex and women's rights activists, independence activists and spies, and ordinary people appear.

Many of the novels, movies, and songs they enjoyed are also cited.

All of these things unfold like a drama, a story of “being caught up in history, making history, and eventually becoming history.”

This book is a compilation of 18 selected and supplemented articles from the series [Cho Hyung-geun's 'The Back Pages of History'] published in Sisa IN from May 2023 to August 2024.

This book, which focuses on recreating the complexities of individual hearts rather than major historical events, does not feature pure evil or pitiful victims.

However, it is full of three-dimensional figures of people who love, make mistakes, dream, and desire in the whirlwind of history, and the story that unfolds as they pass by and become intertwined with each other.

Choices, sometimes noble and sometimes vile, and the chain of events they bring about create and change history, crossing all the boundaries that constitute existing historical narratives: nation and people, good and evil, victory and defeat, harm and harm done.

The 'Bridge on the River Kwai' used in the title also shows a page of history that transcends boundaries.

In 1942, during the height of World War II, the Japanese army, which had occupied Southeast Asia, was looking beyond Burma (Myanmar) and even into India.

To this end, it was decided to build the Thailand-Burma Railway and forcibly mobilize Allied prisoners of war and local civilians.

Tens of thousands of people died in the difficult construction in rough terrain.

It is not well known that there were about 1,000 Koreans on that 'Death Railway'.

Those who were forcibly conscripted and worked as prisoner guards were beaten by the Japanese military, abused prisoners, and led the scene.

For some British prisoners of war, the most horrific sight of the perpetrator was also the face of a Korean.

After the war, they were subject to war crimes trials.

It is extremely unfair considering that they were drafted there and that many of their Japanese superiors were released without even being tried.

But does this mean there's no accountability for violence committed on orders? Above all, the parties involved didn't think so.

He visited the abused prisoners and apologized, while also holding the Japanese government accountable.

He was outraged by the violence he suffered and sought to take responsibility for the violence he committed.

They were not the only ones who became parties to overlapping destinies in the turbulent waves of history.

The story continues endlessly, revealing the diverse aspects of humanity that are difficult to capture with the logic of nation or race, good and evil, victim and perpetrator, and more: Japanese peace activist Li Xianglan (Yoshiko Yamaguchi), who became a star of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo while hiding her identity and actively intervened in resolving the comfort women issue after the war; Fritz Haber, a Jew who dramatically increased food production by developing nitrogen fertilizer and invented a method for producing chlorine gas, ushering in an era of mass slaughter; Yun Chi-ho, an enlightened intellectual who internalized the law of the jungle and publicly defended the divorced women Na Hye-seok and Park In-deok despite public criticism; Marlene Dietrich, a Hollywood star who contributed to Western men's fantasies about Asian women and a German who stood up to the Nazis; Leni Riefenstahl, a Nazi collaborator who dedicated herself to documenting the disappearing lives of indigenous Africans; and Gunter Grass, a Nazi SS member who became the "conscience of postwar Germany."

The great forces of history and the turbulent events are ultimately human stories.

This book was written as a human story.

Stories unfold of many characters becoming embroiled in history, making history, and eventually becoming history.

We are intertwined and the world is not simple.

I tried not to portray them as pure demons or pitiful victims.

I tried to understand them as human beings who love and make mistakes, as human beings with dreams and desires.

I tried to see together the historical responsibility they must bear and the responsibility history must bear them. (From the [Introduction])

Beyond indifference and sympathy

Reading a Common History as an 'Involved Subject'

When we talk about the imperialist period, we always take a clear position.

The facts of harm and harm are clearly distinguished, and the past is understood as a matter of demands rather than responsibility.

Acknowledging the damage and providing appropriate compensation is said to be the most appropriate way to overcome this period.

This book argues that a true break with this period is possible only when we move beyond the familiar perspective that sees the invasion of imperialist powers as the sole cause of the problem and use it as an opportunity for reflection to understand and reflect on the contemporary thought systems, perceptions, and sensibilities that made such violence possible.

For example, Chapter 9, 'Will Science Save Us?', examines the last scene of the novel 'Heartless', which interprets 'science' as 'power', Lee Kwang-soo's interest in Nazism and fascism, the Hwang Woo-suk boom and the superconductor controversy, and the life of Fritz Haber, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist who saved humanity from a food crisis and a Jew who opened the era of chemical warfare and mass genocide by developing chlorine gas. It makes us look back on the colonialism that still operates powerfully in a history that has reduced science only to power and competitiveness.

The history of sexual exploitation that emerged from Western men's fantasies about Oriental women, which blossomed in the Japanese concession of Shanghai, and the various cultural products that responded to them, and this Orientalist sensibility led to the "Pang Pang Girl" career women serving American soldiers in Japan, the "Elena" princess in South Korea, and the "Miss Saigon" in Vietnam, is also a theme that is repeatedly addressed throughout this book.

This makes us reflect on what "coming to terms with the past" means to those who have been mobilized and forgotten by the state, and how much we can alienate ourselves from this history in the present context.

Another important attempt of this book is to remind us that, as subjects of memory, we are always implicated in history.

A prime example is the way Korea and the United States remember the Vietnam War in public settings.

This is a selective memory that only commemorates and pities the veterans while omitting the Vietnamese victims, those who refused to be dragged into an immoral war and chose to go to prison, and anti-war activists, as well as the disparate responses to memorial services for Vietnam War veterans and the Japanese Prime Minister's visit to Yasukuni Shrine.

The author argues that our way of remembering war is intertwined with a reality where we express "national mourning" for repeated disasters, but fail to reflect on the structures that cause such tragedy.

This book shows that we can avoid repeating the past only when we thoroughly reflect on the historical responsibility we must bear, as well as the responsibility that history must bear to us, beyond indifference or sympathy. This also begins with deciding what to remember and how to remember it.

Looking back on the history of catastrophe

Flashes of light and attitude

Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist, said that everything can be taken from a human being but one thing: the freedom to choose and act in any given situation.

This book, which delicately follows the minds and attitudes of "ordinary people," is also a precious record that introduces a legacy of the mind, a flash of brilliance not recorded in capital-letter history, worthy of re-examination.

The granddaughter of Fritz Haber, the genius scientist who ushered in the era of chemical warfare and mass murder, devoted herself to developing an antidote to the poison gas her grandfather had created, but committed suicide when she heard that the research budget was being prioritized for the development of the atomic bomb. (p. 158) A British prisoner of war recalls the moment when, while being transported on a cargo ship bound for the River Kwai, a Korean guard opened the train door without his superiors knowing, as he was suffocating.

I remembered the pleasant breeze that blew then, the fact that no one escaped through the open door, and the sight of the prisoners quickly closing the door after arriving so as not to embarrass the guards. (Page 65) It is not a story that is remembered in official history, but someone remembered this moment for a long time and recorded it.

This book places these 'minor' choices on the stage of history and allows us to imagine other possibilities.

By looking back and remembering the small choices that transcended boundaries of ideology, nationality, and race and moved toward the "universal," wouldn't we perhaps have a very different history?

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 31, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 312 pages | 380g | 135*210*16mm

- ISBN13: 9791172131166

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)