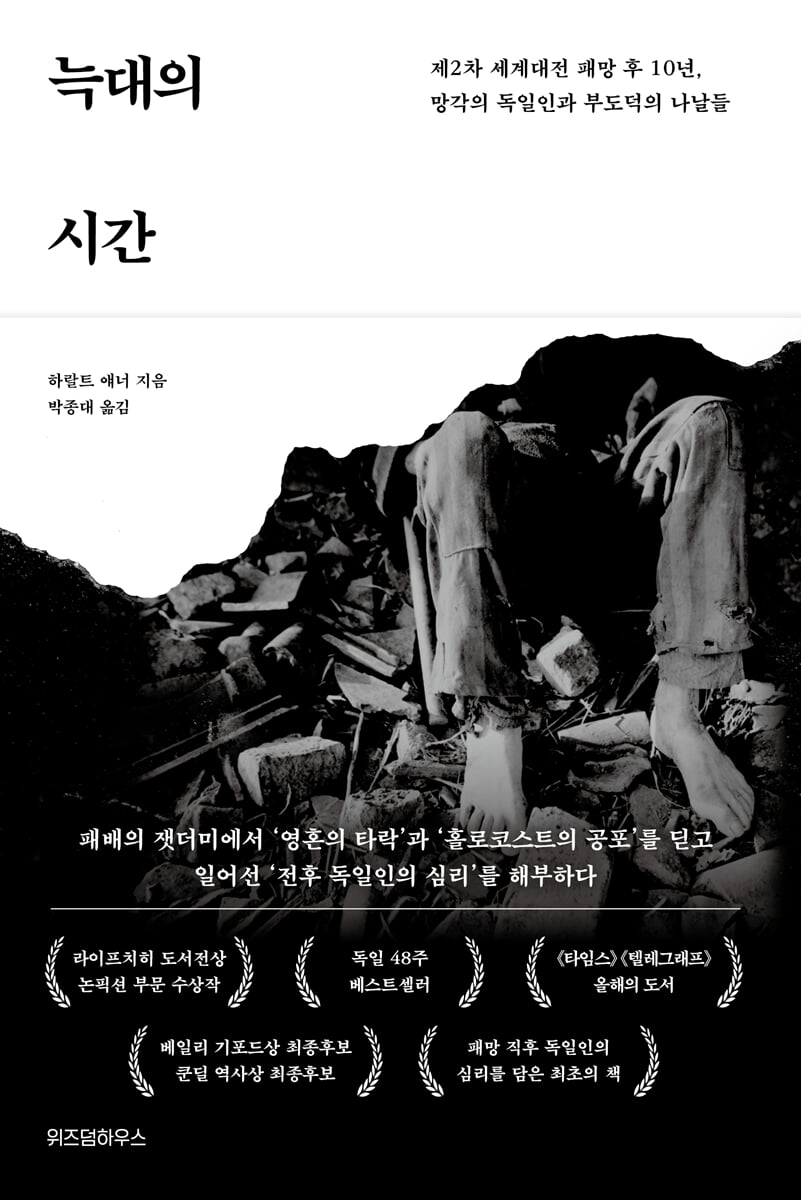

Wolf's Hour

|

Description

Book Introduction

Rising from the ashes of defeat, overcoming the ‘corruption of the soul’ and the ‘horror of the Holocaust’ The first historical book to dissect the psychology of postwar Germans This book provides a panoramic view of the reconstruction efforts and social divisions Germany endured over the ten years from May 8, 1945, the day Germany was defeated in World War II, the so-called "zero hour," to 1955. How did the Germans abandon "Nazis" and create a new "Germany"? Was Germany's economic miracle entirely due to thorough self-reflection and diligence? Was the Germans' reckoning with their past truly "exemplary"? What processes did Germany undergo after its defeat to create the nation we now call "Germany"? This book revisits scenes from that history, revealing a Germany quite different from the one we commonly perceive. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: Happiness Through Misfortune 7

1.

Zero time?

Countless Beginnings and Endings · 19 | People Who Experienced Hell · 28

2.

In the ruins

Who Will Clean Up the Massive Debris? · 37 | The Beauty of Ruins and Debris Tourism · 55

3.

Great Migration

People Who Lost Their Homes Forever · 71 | Freed Forced Laborers and Wandering Prisoners · 78 | A Shocking Encounter with Oneself · 102 | A Life of Poverty on the Road · 124

4.

dance craze

The Bubbling Joy of Life · 139 | The Wild Party on the Ashes · 149

5.

Love in a Destroyed City

The Return of Exhausted Men · 171 | Constanze, A Voice for Women · 185 | Hungry for Life, Thirsty for Love · 191 | The Age of Female Excess · 199 | The "Time of Humiliation" Experienced by Eastern Women · 209 | Veronika Dankeschön, the Yankee Lover of the West · 216

6.

Looting, Distribution, and Black Markets: Lessons for a Market Economy

The Beginning of Redistribution: Learning to Plunder · 237 | The Logic of Food Rationing · 243 | The Birth of a Nation of Thieves · 252 | The Black Market as a Citizen's School · 271

7.

Economic Miracle and Concerns about Immorality

Currency Reform, the Second Zero Hour · 285 | Wolfsburg, the Human Farm · 296 | Using Couples' Sex as a Business Model · 321 | Fear of Moral Decay · 332

8.

Re-educators

The Allied Reform of Germany's Spirit · 343 | Strangers Returning Home · 360

9.

The Cold War in Art and the Design of Democracy

Longing for Culture · 385 | Abstract Art and the Social Market Economy · 393 | How Kidney Tables Changed Our Minds · 414

10.

The sound of oppression

Fascism Vanishes Like Air · 425 | Silence, Words, and Unwilling Closeness · 434 | Denazification and Democracy · 451

Conclusion: Life Goes On 460

Week 466

Reference 507

521 Images and Quotes

Search 522

1.

Zero time?

Countless Beginnings and Endings · 19 | People Who Experienced Hell · 28

2.

In the ruins

Who Will Clean Up the Massive Debris? · 37 | The Beauty of Ruins and Debris Tourism · 55

3.

Great Migration

People Who Lost Their Homes Forever · 71 | Freed Forced Laborers and Wandering Prisoners · 78 | A Shocking Encounter with Oneself · 102 | A Life of Poverty on the Road · 124

4.

dance craze

The Bubbling Joy of Life · 139 | The Wild Party on the Ashes · 149

5.

Love in a Destroyed City

The Return of Exhausted Men · 171 | Constanze, A Voice for Women · 185 | Hungry for Life, Thirsty for Love · 191 | The Age of Female Excess · 199 | The "Time of Humiliation" Experienced by Eastern Women · 209 | Veronika Dankeschön, the Yankee Lover of the West · 216

6.

Looting, Distribution, and Black Markets: Lessons for a Market Economy

The Beginning of Redistribution: Learning to Plunder · 237 | The Logic of Food Rationing · 243 | The Birth of a Nation of Thieves · 252 | The Black Market as a Citizen's School · 271

7.

Economic Miracle and Concerns about Immorality

Currency Reform, the Second Zero Hour · 285 | Wolfsburg, the Human Farm · 296 | Using Couples' Sex as a Business Model · 321 | Fear of Moral Decay · 332

8.

Re-educators

The Allied Reform of Germany's Spirit · 343 | Strangers Returning Home · 360

9.

The Cold War in Art and the Design of Democracy

Longing for Culture · 385 | Abstract Art and the Social Market Economy · 393 | How Kidney Tables Changed Our Minds · 414

10.

The sound of oppression

Fascism Vanishes Like Air · 425 | Silence, Words, and Unwilling Closeness · 434 | Denazification and Democracy · 451

Conclusion: Life Goes On 460

Week 466

Reference 507

521 Images and Quotes

Search 522

Detailed image

Into the book

Today we know a lot about the Holocaust.

On the other hand, we do not know much about how contemporaries continued to live in the shadow of the Holocaust.

How could a nation that had previously murdered millions in its name ever speak of morality and culture? How could they, with any conscience, ever speak of such things again? Shouldn't they have left it up to their children to decide for themselves what is good and what is bad?

--- p.15, from “Introductory Remarks”

People who wore uniforms in the past now quickly take them off, burn them, or dye them a different color.

High-ranking officials committed suicide by drinking poison, while lower-ranking officials threw themselves out of windows or cut their arteries.

The 'blank period' has begun.

The law was suspended and there was no one in charge of anything.

Nothing belonged to anyone.

The first person to lie down and occupy the place was the owner.

No one took responsibility and no one protected them.

The old power has fled, and the new power has not yet arrived.

Only the sound of cannons heralded the coming of a new power.

Now even decent and respectable people are out to plunder.

People swarmed the food stores and roamed abandoned houses looking for food and shelter.

--- p.22~23, 「1.

From "Zero Time?"

How the debris is disposed of also affects the economic development of the city.

Frankfurt, for example, did not become the capital of West Germany in 1949 as it had hoped, but instead emerged as the "capital of the economic miracle," thanks in part to the way it handled the rubble.

The city's residents have shown that money can be made from war debris.

At first it seemed like they were just letting go.

While authorities in other cities have urged residents to grab shovels and get to work cleaning up, Frankfurt officials have taken a different approach.

It was a scientific method.

They analyzed, pondered, and experimented.

(…) Frankfurt chemists discovered that by dissolving the debris they could obtain gypsum, which would break down into sulfur dioxide and calcium oxide, and thus produce a cement aggregate that could be sold at a very good price when the decomposition process was complete.

--- p.50, 「1.

From "In the Ruins"

The millions of books that the Nazis confiscated from Jewish communities across Europe and moved to German libraries and museums were a treasure of immense historical significance to Jews.

Therefore, various Jewish organizations were established with American support to identify the destroyed Jewish cultural heritage, reclaim it from Germany, and manage it on their own.

However, when Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt visited Germany on this mission as chair of the Committee for the Reconstruction of Jewish Culture, she became embroiled in a serious feud between two Jewish communities that had just survived the Holocaust.

The dispute concerned Jewish identity and unity, which were crucial to both sides.

Because of this, the Munich Jews, although they had benefited from the Eastern Orthodox in many ways, wanted them to leave for Palestine as soon as possible.

--- p.92, 「3.

From "The Great Migration"

If you watch movies from the post-war era, you'll almost always see people like thugs, black marketeers, and underworld criminals enjoying parties.

They eat thick cutlets, drink smuggled wine, and bury their noses in women's swaying breasts, with greedy, oily faces like those in George Grosz's Weimar-era caricatures.

In this respect, dancing and parties were portrayed as the lewd pastimes of the unscrupulous nouveau riche, automatically taboo in a state of general poverty.

But the reality was completely different.

Even people who had nothing enjoyed the party.

Of course, not everyone did that.

--- p.144, 「4.

From "Dance Fever"

The typical image of a returnee was always that of a gloomy and ungrateful type.

They often felt unwell and would just lie on the sofa and roll around.

If there's still a sofa left.

They made life hell for families who had been desperately waiting for their husbands and fathers to return.

He made his family members feel every day how much he had suffered.

Few people expected this world when they returned home.

The world had completely changed.

Everything was destroyed by bombing, and the country was occupied by foreign countries.

Above all, it was now a country run by women.

The returnees were more angry than happy that their wives had managed to raise their families without them.

Because through that process, my wife changed into a different person.

--- p.174, 「5.

From "Love in the Destroyed City"

There were also cultural or subcultural motivations behind the young German women's search for American soldiers.

That is to say, there was also a desire to escape from the monotonous German way of life and the cramped, stifling environment.

But most German historians have long since given up on the idea that women at the time possessed a desire for the unfamiliar, and that this might be precisely what attracted them to American soldiers.

They did not, and still do not, acknowledge that Americans, even black men, could be attracted to them for reasons other than a desire for chocolate.

For them, 'poverty' was the only motive for forced labor.

So, isn't it possible that we still have the impulse to view women who voluntarily seek out the Yankees as traitors to their nation?

--- p.224, 「5.

From "Love in the Destroyed City"

Theft was also subtly categorized according to type, but the standards were clear.

One's own possessions must be protected, but one can take others' possessions.

If someone stole a shell and made it their own, it should be protected, but the shells loaded onto a truck as the property of an unknown public institution did not need such protection, which was the collective legal consciousness of the Germans at the time.

In other words, taking coal from a truck is a self-rescue measure taken in an emergency evacuation situation, while taking coal from a person's basement is theft.

People in the post-war era liked to compare themselves to animals, either good or bad.

The person who stole potatoes from the field was a hamster who diligently gathered food, and the person who took things from such a hamster was a hyena.

Between the two, there was a wolf whose sociality was questionable, and the 'lone wolf' was as notorious as the pack.

--- p.266, 「6.

From “Looting, Distribution, and Black Market”

Wolfsburg's history began in 1938.

Hitler wanted a people's car that many people could afford.

New cars had to cost less than 1,000 marks, be reliable, have a long lifespan, be fuel efficient, and have air-cooled engines.

It is said that Hitler even drew and showed a model of a round beetle-shaped car.

However, established German car manufacturers opposed this plan, deciding that the car could not be produced at that price.

Hitler, on the other hand, believed that automakers were incapable of producing such a people's car because they were obsessed with luxury cars (and so was Hitler himself).

--- p.298, 「7.

From “Economic Miracle and Concerns about Immorality”

The Americans had no intention of giving the Germans a chance to reintegrate immediately after the war.

They had no communist theory of history that saw the Germans as victims of Hitler.

On the contrary, he assumed that even ordinary Germans had cold-blooded, militaristic, and authoritarian tendencies, and he thought that the form of government most suitable for such tendencies was a Führer state.

In any case, the Germans were not yet ready for democracy, and until then it would remain a great danger to world peace.

Therefore, all Germans were considered enemies in principle.

--- p.351, 「8.

Among the "re-educators"

Even in the realm of art, Cold War front lines were formed.

As East and West Germans grew increasingly distant, it became easier for abstract art to gain traction in West Germany.

As the principles of East German figurative art became clearer, it became easier for abstract art to establish itself as an aesthetic alternative to the political system and to rise as the representative art form of West Germany.

Abstract art, understood as the art of freedom, acquired a charisma similar to a confession of faith, and this charisma became more persuasive when it drew a clear line with politics.

Abstract art depicted the playful celebration of existence, embodying the pure life energy freely erupting on large canvases.

It was also an expression of luxury, an excessive use of materials, by applying the paint by scooping it out with a spatula, dripping it, or applying it in thick layers on the surface.

Luxury was a yearning for a higher form of abundance, while also freeing us from the shackles of frugality that had long been an internal compulsion of the postwar era.

--- p.406, 「9.

From “Art: The Cold War and the Design of Democracy”

A female exile who returned to the United States in 1949 felt, despite her brief six-month visit, that the Germans' inability to speak out about the persecution of the Jews was a bitter denial of her own existence.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt, who, as a Jew, had to leave Germany in 1933, served as chair of the Committee for Jewish Cultural Reconstruction,11 and reported to various American institutions on the “aftereffects of Nazi rule.”12 She was appalled by the state of mind of the German people, except in Berlin, where they “still hated Hitler,” where freethinking flourished, and where resentment toward the victorious powers was barely felt.

The pervasive indifference, the general lack of emotion, the overt coldness in his eyes were merely “the most striking outward symptoms of a deep-seated, stubborn, and sometimes barbaric inability to face and accept what had actually happened.”

A shadow of deep mourning fell over all of Europe, but not Germany.

Instead, in Germany, a diligence bordering on madness was used to deny reality.

Arendt argued that this “inability to mourn,” as the social psychologists Alexander and Margarete Michellich later termed it, had left Germans “living ghosts who no longer respond to words, arguments, or even to the genuinely sad gaze of human beings.”

On the other hand, we do not know much about how contemporaries continued to live in the shadow of the Holocaust.

How could a nation that had previously murdered millions in its name ever speak of morality and culture? How could they, with any conscience, ever speak of such things again? Shouldn't they have left it up to their children to decide for themselves what is good and what is bad?

--- p.15, from “Introductory Remarks”

People who wore uniforms in the past now quickly take them off, burn them, or dye them a different color.

High-ranking officials committed suicide by drinking poison, while lower-ranking officials threw themselves out of windows or cut their arteries.

The 'blank period' has begun.

The law was suspended and there was no one in charge of anything.

Nothing belonged to anyone.

The first person to lie down and occupy the place was the owner.

No one took responsibility and no one protected them.

The old power has fled, and the new power has not yet arrived.

Only the sound of cannons heralded the coming of a new power.

Now even decent and respectable people are out to plunder.

People swarmed the food stores and roamed abandoned houses looking for food and shelter.

--- p.22~23, 「1.

From "Zero Time?"

How the debris is disposed of also affects the economic development of the city.

Frankfurt, for example, did not become the capital of West Germany in 1949 as it had hoped, but instead emerged as the "capital of the economic miracle," thanks in part to the way it handled the rubble.

The city's residents have shown that money can be made from war debris.

At first it seemed like they were just letting go.

While authorities in other cities have urged residents to grab shovels and get to work cleaning up, Frankfurt officials have taken a different approach.

It was a scientific method.

They analyzed, pondered, and experimented.

(…) Frankfurt chemists discovered that by dissolving the debris they could obtain gypsum, which would break down into sulfur dioxide and calcium oxide, and thus produce a cement aggregate that could be sold at a very good price when the decomposition process was complete.

--- p.50, 「1.

From "In the Ruins"

The millions of books that the Nazis confiscated from Jewish communities across Europe and moved to German libraries and museums were a treasure of immense historical significance to Jews.

Therefore, various Jewish organizations were established with American support to identify the destroyed Jewish cultural heritage, reclaim it from Germany, and manage it on their own.

However, when Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt visited Germany on this mission as chair of the Committee for the Reconstruction of Jewish Culture, she became embroiled in a serious feud between two Jewish communities that had just survived the Holocaust.

The dispute concerned Jewish identity and unity, which were crucial to both sides.

Because of this, the Munich Jews, although they had benefited from the Eastern Orthodox in many ways, wanted them to leave for Palestine as soon as possible.

--- p.92, 「3.

From "The Great Migration"

If you watch movies from the post-war era, you'll almost always see people like thugs, black marketeers, and underworld criminals enjoying parties.

They eat thick cutlets, drink smuggled wine, and bury their noses in women's swaying breasts, with greedy, oily faces like those in George Grosz's Weimar-era caricatures.

In this respect, dancing and parties were portrayed as the lewd pastimes of the unscrupulous nouveau riche, automatically taboo in a state of general poverty.

But the reality was completely different.

Even people who had nothing enjoyed the party.

Of course, not everyone did that.

--- p.144, 「4.

From "Dance Fever"

The typical image of a returnee was always that of a gloomy and ungrateful type.

They often felt unwell and would just lie on the sofa and roll around.

If there's still a sofa left.

They made life hell for families who had been desperately waiting for their husbands and fathers to return.

He made his family members feel every day how much he had suffered.

Few people expected this world when they returned home.

The world had completely changed.

Everything was destroyed by bombing, and the country was occupied by foreign countries.

Above all, it was now a country run by women.

The returnees were more angry than happy that their wives had managed to raise their families without them.

Because through that process, my wife changed into a different person.

--- p.174, 「5.

From "Love in the Destroyed City"

There were also cultural or subcultural motivations behind the young German women's search for American soldiers.

That is to say, there was also a desire to escape from the monotonous German way of life and the cramped, stifling environment.

But most German historians have long since given up on the idea that women at the time possessed a desire for the unfamiliar, and that this might be precisely what attracted them to American soldiers.

They did not, and still do not, acknowledge that Americans, even black men, could be attracted to them for reasons other than a desire for chocolate.

For them, 'poverty' was the only motive for forced labor.

So, isn't it possible that we still have the impulse to view women who voluntarily seek out the Yankees as traitors to their nation?

--- p.224, 「5.

From "Love in the Destroyed City"

Theft was also subtly categorized according to type, but the standards were clear.

One's own possessions must be protected, but one can take others' possessions.

If someone stole a shell and made it their own, it should be protected, but the shells loaded onto a truck as the property of an unknown public institution did not need such protection, which was the collective legal consciousness of the Germans at the time.

In other words, taking coal from a truck is a self-rescue measure taken in an emergency evacuation situation, while taking coal from a person's basement is theft.

People in the post-war era liked to compare themselves to animals, either good or bad.

The person who stole potatoes from the field was a hamster who diligently gathered food, and the person who took things from such a hamster was a hyena.

Between the two, there was a wolf whose sociality was questionable, and the 'lone wolf' was as notorious as the pack.

--- p.266, 「6.

From “Looting, Distribution, and Black Market”

Wolfsburg's history began in 1938.

Hitler wanted a people's car that many people could afford.

New cars had to cost less than 1,000 marks, be reliable, have a long lifespan, be fuel efficient, and have air-cooled engines.

It is said that Hitler even drew and showed a model of a round beetle-shaped car.

However, established German car manufacturers opposed this plan, deciding that the car could not be produced at that price.

Hitler, on the other hand, believed that automakers were incapable of producing such a people's car because they were obsessed with luxury cars (and so was Hitler himself).

--- p.298, 「7.

From “Economic Miracle and Concerns about Immorality”

The Americans had no intention of giving the Germans a chance to reintegrate immediately after the war.

They had no communist theory of history that saw the Germans as victims of Hitler.

On the contrary, he assumed that even ordinary Germans had cold-blooded, militaristic, and authoritarian tendencies, and he thought that the form of government most suitable for such tendencies was a Führer state.

In any case, the Germans were not yet ready for democracy, and until then it would remain a great danger to world peace.

Therefore, all Germans were considered enemies in principle.

--- p.351, 「8.

Among the "re-educators"

Even in the realm of art, Cold War front lines were formed.

As East and West Germans grew increasingly distant, it became easier for abstract art to gain traction in West Germany.

As the principles of East German figurative art became clearer, it became easier for abstract art to establish itself as an aesthetic alternative to the political system and to rise as the representative art form of West Germany.

Abstract art, understood as the art of freedom, acquired a charisma similar to a confession of faith, and this charisma became more persuasive when it drew a clear line with politics.

Abstract art depicted the playful celebration of existence, embodying the pure life energy freely erupting on large canvases.

It was also an expression of luxury, an excessive use of materials, by applying the paint by scooping it out with a spatula, dripping it, or applying it in thick layers on the surface.

Luxury was a yearning for a higher form of abundance, while also freeing us from the shackles of frugality that had long been an internal compulsion of the postwar era.

--- p.406, 「9.

From “Art: The Cold War and the Design of Democracy”

A female exile who returned to the United States in 1949 felt, despite her brief six-month visit, that the Germans' inability to speak out about the persecution of the Jews was a bitter denial of her own existence.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt, who, as a Jew, had to leave Germany in 1933, served as chair of the Committee for Jewish Cultural Reconstruction,11 and reported to various American institutions on the “aftereffects of Nazi rule.”12 She was appalled by the state of mind of the German people, except in Berlin, where they “still hated Hitler,” where freethinking flourished, and where resentment toward the victorious powers was barely felt.

The pervasive indifference, the general lack of emotion, the overt coldness in his eyes were merely “the most striking outward symptoms of a deep-seated, stubborn, and sometimes barbaric inability to face and accept what had actually happened.”

A shadow of deep mourning fell over all of Europe, but not Germany.

Instead, in Germany, a diligence bordering on madness was used to deny reality.

Arendt argued that this “inability to mourn,” as the social psychologists Alexander and Margarete Michellich later termed it, had left Germans “living ghosts who no longer respond to words, arguments, or even to the genuinely sad gaze of human beings.”

--- p.433~434, 「10.

From "The Sound of Oppression"

From "The Sound of Oppression"

Publisher's Review

From the age of barbarism to the age of citizenship,

What did post-war Germans forget and how did they recover?

The Germans, who had been united until the end of the war, were completely divided when the war ended.

The old order was gone, but the new order was still vague, and this time was called the "Hour of the Wolf," meaning "humans were wolves to everyone else."

After the war, more than half of Germans remained in their former places.

Adding the 10 million forced laborers to those who died in the bombings, fled, were exiled, or were forcibly relocated, the total number reached 40 million.

How could people who had been expelled, dragged away, and then released, only to find new homes, rediscover their civic identity? It was a time when they had to create a new society, as entirely new members, amidst chaos.

The author focuses on the story of this period.

The most significant changes began in our daily lives.

It arose from procuring food, from plunder, from exchange, from purchase.

Love is the same.

The end of the war brought a flood of sexual adventure, but also a bitter disappointment for the men who had longed to return home.

People wanted to start over, and divorce rates skyrocketed.

Families were torn apart, life's order was shattered, and human relationships were lost, but people came together again, and the young and courageous enjoyed the adventure of finding their own happiness every day amidst the chaos of the ashes.

The impact of the Holocaust on the consciousness of post-war Germans was surprisingly minimal.

They avoided the Holocaust for their own 'suspicious happiness' and portrayed themselves as victims.

Yet the postwar era was more contentious, life more open, and intellectuals more critical than previously thought.

The spectrum of opinion was wider and the art was more innovative.

It was through this conscious suppression and distortion that the anti-fascist and trust-inspiring Germany of today was born.

This book sheds new light on the forgotten Germany between 1945 and 1955 by examining from various angles the reconstruction work Germany had to endure in the ten years immediately following the war and the divided mentality of the German people during that time.

Through extensive sources and meticulous interpretations, including not only official documents and published books, but also diaries, memoirs, literary works, newspapers, magazines, video footage, and even popular song lyrics, this book provides a fresh perspective on how Germany transcended that period and became the Germany of today.

The virtue of this book is that it vividly captures the atmosphere of the times, as if it were within reach, through the personal accounts of not only famous people like Thomas Mann and Hannah Arendt, but also lesser-known ordinary people.

There was no self-reflection as we know it.

Germans who advocated a cartel of silence and scapegoat logic regarding the Holocaust

In January 1947, the German magazine Der Standpunkt published an article asking:

“Why are Germans so unpopular with the world?” The article answers the question by saying that Germany is “Europe’s problem child and the world’s scapegoat,” and that “just like in any family, in the international community, there are children who are loved and there are children who are hated.”

How could Germany, a country that prides itself on being "the world's leading exporter of reconciliation," pose such a question so soon after the Holocaust, which slaughtered millions of Jews? What kind of mental structure exists within someone who reduces a world war to a "domestic feud" and dismisses the perpetrators as mere "problem children"?

Immediately after Germany's official defeat on May 8, 1945, the so-called "zero hour," the Germans were confronted with a pile of ruins measuring approximately 500 million cubic meters.

Having experienced 60 million deaths in the war, the wave of rape that began with the arrival of the Red Army, the occupation of Germany by the Western Allies, and the hell known as the "Hunger Winter" of 1946 and 1947, Germans did not hesitate to consider themselves "victims" as if the Holocaust had never existed.

Their logic was that they were simply victims of National Socialism, which was like a 'poison' that paralyzed people, of Nazism, which was like a 'drug' that tamed people into obedient tools, and of the 'evil' called Hitler.

“No people’s soul has been so often and so deeply plowed by fate as that of the German people, preparing the soil for the seeds of a new spirit to sprout.”_Page 430

The press, books, and papers of the time were full of articles that described the suffering of the German people in such a superlative way that no other people could match it.

This is because they believed that the darker they portrayed that period, the lighter their mistakes, responsibilities, and guilt would be.

The previous article in "Perspective" was a psychological expression of the victim logic, conscious suppression of the Holocaust, and collective silence that the Germans adopted in the face of this desperate desire for survival.

Even post-war Germans, when they look back on the old days, often portray themselves as the "Great Silencers," who had to endure what they had experienced in silence.

But in reality, silence was selective only in the case of the Holocaust.

Rather, the fact that they had escaped death made most people enjoy an unprecedentedly hot 'joy of life'.

Within a fortnight of the surrender, movie theaters reopened amidst the ruins, and within two months, dance halls were open enough to accommodate all-night tours.

In Cologne, where only about 5% of the post-war population survived, a small 'carnival procession' was already taking place among the eerie rubble in 1946, while in Berlin the 'Fantasy Ball' took place the same year.

By 1947, people were already going on vacation to resorts.

Of the 10,000 or so holiday homes on Sylt, 6,000 were occupied by refugees, while the rest were occupied by holidaymakers.

The author argues that in the decades immediately following the collapse, there was no widespread social debate about the massacre of millions of people.

The liquidation of the past only began with the Auschwitz trials, which took place from 1963 to 1968.

This too was not so much a product of thorough self-reflection as a historic victory over the parental generation, sparked by the anger of the '68 generation, like the leaflets plastered on the streets in 1967 that read, "Let's launch a movement of disobedience against the Nazi generation."

In other words, the German settlement of its past, which we cite as an example, was the aftereffect of the oppression that the German people inflicted on themselves after 1945.

“Moral collapse and distortion of collective awareness”

An Autopsy of the Post-War German Mentality Through an Insider's Eyes

Naturally, the war completely shook many social concepts in Germany.

The most representative example is ‘moral concept’.

The 'honesty' that we often think of as a characteristic of Germans today was not applicable to post-war Germans.

Germans, who had not known what starvation was until their defeat, felt the 'fear of death' for the first time after the war when their supply chain was destroyed and the Allies drastically reduced food rations.

To survive, the Germans had to learn new survival skills: pillaging, black market trading, and petty theft.

During the 'power vacuum' after the defeat and just before the Allied occupation, the Germans were obsessed with 'plunder'.

Amidst extreme anxiety about what might happen next, people frantically ransacked government buildings, stockpiles, freight trains, farms, and even neighbors' homes.

This was so common that the diary of an ordinary 18-year-old German woman recorded a plundering expedition she went on with her friends and neighbors.

The Allied forces soon stabilized the social system by normalizing administrative institutions, but the moral collapse showed no signs of stopping.

Especially for the three years immediately following the end of the war, Germans were constantly suffering from hunger because they were only given a minimum of 800 calories per person.

People resorted to a variety of generally immoral means of self-preservation, including a 'thieving tour' to the countryside.

City dwellers, unable to buy what they wanted no matter how much money they had, boarded trains to steal the crops of rural farmers.

A hole soon appeared in the gap between the food ration cards.

The black market was overflowing with goods embezzled or smuggled from Allied PXs, and forged food ration cards were circulating in large quantities.

People of this period spoke of the arrival of the 'hour of the wolf', the time when 'humans in their natural state are wolves to other humans'.

It meant that a complete collapse of legal consciousness and moral sentiment was imminent.

“Everyone who didn’t freeze to death stole.

If everyone is a thief, can we really accuse each other of being thieves?”_Page 261

In 1947, criminologist Hans von Hentig published an article expressing concern about the “normalization of crime,” stating that “the scale and form of crime in Germany is unprecedented in the history of Western civilization.”

Countless debates about the Germans' loss of legal consciousness and sense of guilt can be found in magazines, academic books, newspapers, and memoirs of the time.

But if we look at this debate from a historical distance, away from the specifics of post-war German daily life, the debate itself seems absurd.

The fact that in Germany alone 500,000 Jews were looted or driven from their homes, and 165,000 of them murdered, is not mentioned at all in the search for reasons for the disappearance of the legal consciousness.

Even after the defeat, when the world had long since stigmatized the "Germans" as perpetrators of war crimes and genocide, Germans still believed that their country possessed order and dignity.

While the post-war collapse of the system was viewed abroad as an opportunity to resocialize Germany, the fact that Germans now feared that they had fallen into a pit of crime shows how severe the distortion of collective perception was at the time.

The Whereabouts of Jews in Concentration Camps and the Social Role of Wartime Emigrants

This is how the foundation of civil society was laid.

While the Germans enjoyed a dubious happiness amidst their poverty, the repatriation of 8 to 10 million forced laborers also began.

They were 7 million foreigners and Jews who were brought in to solve the labor shortage during the war.

Although 107,000 Jews were transported home each day, many chose to remain in the camps.

The reasons why Jews remained in the camps varied.

Most of them had nowhere to return to, and many were unable to endure the transfer due to mental or physical weakness.

The US military established new camps for Jewish survivors, most notably the Förrenwald concentration camp near Munich, on the grounds that "Jews suffered far more at the hands of the Nazis than did other non-Jewish populations of the same nationality."

Originally a housing complex for a dye company, Förrenwald was more like a concentration camp than a small Jewish community.

It had 15 streets, including Kentucky Street and New York Street, and had its own administrative body, political party, police force, courts, hospital, staff training center, school, theater, sports club, and even a newspaper in Yiddish.

When Israel was established in 1948, many Jews left, but others returned.

These were people who had not been able to adapt to a free life after living in a concentration camp for over a decade, and who longed for the 'passive life' in the concentration camp where others took care of their lives and protected them.

In addition to these forced conscripts, the total number of people for whom the Allied Powers had to take responsibility after the war exceeded 40 million.

Immediately after the war, Germany was entangled in another diaspora: refugees, the homeless, deserters, displaced persons forcibly relocated when eastern Germany became Polish territory after the Yalta and Potsdam conferences, and Jewish refugees flooding into Germany due to anti-Semitism and genocide.

In addition, racism, regionalism, and tribalism were still rampant, and even people at the time could not have imagined that social integration would be possible.

And yet, the ‘miracle of unification’ happened.

The most important role was played by the 12 million displaced people.

Moved to the countryside under the Allied plan, they served as a catalyst for social modernization despite the hostility of the local indigenous population.

Displaced people also played a role in the enzymatic function of delocalization, the leveling of regional differences, the driving force of the economic miracle, and the unification around a national identity rooted in constitutional patriotism.

Institutional integration soon followed.

In particular, the Burden Adjustment Act, implemented in West Germany in 1952, served more than its original purpose of requiring owners of real estate, houses, and other assets to transfer 50% of their value to those who suffered losses.

The foundation of what would later become known as "civil society" was laid in the redistribution process, where a compromise was reached after fierce and persistent debate.

How were the traces of Nazism, fascism, and the Third Reich erased?

The meticulous planning of the Great Designer Alliance

The Allied Forces were responsible for shaking off the taint of fascism during the transition from the Third Reich to a new democratic republic.

The moment the Allies crossed the German Empire's borders, they already had an elaborate plan in their pocket for managing the conquered territories.

'How can we drive the arrogance out of the Germans?' 'How can we rid their brains of the racism that has been instilled in them over the past twelve years?' As a broad plan to capture the German spirit, the Soviet Union first joined hands with German exile groups such as the 'Ulbricht Group' and took over leaflets, radio speeches, and press agencies one by one.

Some of Ulbricht's group managed to find a usable printer and typewriter in the corpse-strewn press quarters.

How quickly all this happened is evident in the fact that on May 22, just two weeks after the defeat, the first issue of the daily newspaper Berliner Zeitung was published with a circulation of 100,000 copies.

The US military also founded and distributed sixteen new newspapers, with the "Ritchie Boys" receiving advanced training at Camp Ritchie in Maryland.

But unlike the Soviet Union, there was another thing the United States focused on in order to 're-educate' the Germans as a 'promoter of democracy'.

It was art, and specifically, abstract art.

The United States believed that abstract art was not only a good aesthetic program for the "denazification of the imagination," but also a suitable means for opposing the Soviet Union and establishing a separate aesthetic identity for West Germany.

American support for abstract art was comprehensive.

He provided subsidies to young artists, funded exhibitions, and purchased large quantities of their work.

Through sophisticated American operations, lyrical abstraction penetrated even the homes of Germans who still harbored aversion to abstract art.

Abstract patterned curtains, carpets, and tablecloths decorate the interior of the house.

Post-war German homes were soon filled with round, bulbous, curved, and slanted small objects and lightweight furniture such as the "kidney-shaped" kidney table.

Heavy oak furniture, a symbol of fascism, was discarded and a new 'zeitgeist' was placed throughout the house.

It may seem absurd to those who believe that reason is the only effective means of denazification, but as the saying goes, “design determines consciousness,” Germans began to overcome the past and move into the future by changing their environment.

What the author wanted to clarify through this book is clear.

'How could it be possible to escape the psychological state that made the Nazi regime possible, despite the fact that many Germans refused to take personal responsibility?' Here, as crucial as the previous delusions of grandeur, a sudden 'awakening to reality', as if from a dream, played a crucial role.

Moreover, the allure of the laid-back lifestyle that came with the Allies, the bitter process of socialization through the black market, the efforts to integrate displaced people, the heated debates surrounding abstract art, and the excitement of new designs also played a significant role.

All of this fostered a change in the psychological state, and on that basis, political discourse on democracy was able to gradually bear fruit.

This is how those whom we call 'Germany' and 'Germans' today were born.

What did post-war Germans forget and how did they recover?

The Germans, who had been united until the end of the war, were completely divided when the war ended.

The old order was gone, but the new order was still vague, and this time was called the "Hour of the Wolf," meaning "humans were wolves to everyone else."

After the war, more than half of Germans remained in their former places.

Adding the 10 million forced laborers to those who died in the bombings, fled, were exiled, or were forcibly relocated, the total number reached 40 million.

How could people who had been expelled, dragged away, and then released, only to find new homes, rediscover their civic identity? It was a time when they had to create a new society, as entirely new members, amidst chaos.

The author focuses on the story of this period.

The most significant changes began in our daily lives.

It arose from procuring food, from plunder, from exchange, from purchase.

Love is the same.

The end of the war brought a flood of sexual adventure, but also a bitter disappointment for the men who had longed to return home.

People wanted to start over, and divorce rates skyrocketed.

Families were torn apart, life's order was shattered, and human relationships were lost, but people came together again, and the young and courageous enjoyed the adventure of finding their own happiness every day amidst the chaos of the ashes.

The impact of the Holocaust on the consciousness of post-war Germans was surprisingly minimal.

They avoided the Holocaust for their own 'suspicious happiness' and portrayed themselves as victims.

Yet the postwar era was more contentious, life more open, and intellectuals more critical than previously thought.

The spectrum of opinion was wider and the art was more innovative.

It was through this conscious suppression and distortion that the anti-fascist and trust-inspiring Germany of today was born.

This book sheds new light on the forgotten Germany between 1945 and 1955 by examining from various angles the reconstruction work Germany had to endure in the ten years immediately following the war and the divided mentality of the German people during that time.

Through extensive sources and meticulous interpretations, including not only official documents and published books, but also diaries, memoirs, literary works, newspapers, magazines, video footage, and even popular song lyrics, this book provides a fresh perspective on how Germany transcended that period and became the Germany of today.

The virtue of this book is that it vividly captures the atmosphere of the times, as if it were within reach, through the personal accounts of not only famous people like Thomas Mann and Hannah Arendt, but also lesser-known ordinary people.

There was no self-reflection as we know it.

Germans who advocated a cartel of silence and scapegoat logic regarding the Holocaust

In January 1947, the German magazine Der Standpunkt published an article asking:

“Why are Germans so unpopular with the world?” The article answers the question by saying that Germany is “Europe’s problem child and the world’s scapegoat,” and that “just like in any family, in the international community, there are children who are loved and there are children who are hated.”

How could Germany, a country that prides itself on being "the world's leading exporter of reconciliation," pose such a question so soon after the Holocaust, which slaughtered millions of Jews? What kind of mental structure exists within someone who reduces a world war to a "domestic feud" and dismisses the perpetrators as mere "problem children"?

Immediately after Germany's official defeat on May 8, 1945, the so-called "zero hour," the Germans were confronted with a pile of ruins measuring approximately 500 million cubic meters.

Having experienced 60 million deaths in the war, the wave of rape that began with the arrival of the Red Army, the occupation of Germany by the Western Allies, and the hell known as the "Hunger Winter" of 1946 and 1947, Germans did not hesitate to consider themselves "victims" as if the Holocaust had never existed.

Their logic was that they were simply victims of National Socialism, which was like a 'poison' that paralyzed people, of Nazism, which was like a 'drug' that tamed people into obedient tools, and of the 'evil' called Hitler.

“No people’s soul has been so often and so deeply plowed by fate as that of the German people, preparing the soil for the seeds of a new spirit to sprout.”_Page 430

The press, books, and papers of the time were full of articles that described the suffering of the German people in such a superlative way that no other people could match it.

This is because they believed that the darker they portrayed that period, the lighter their mistakes, responsibilities, and guilt would be.

The previous article in "Perspective" was a psychological expression of the victim logic, conscious suppression of the Holocaust, and collective silence that the Germans adopted in the face of this desperate desire for survival.

Even post-war Germans, when they look back on the old days, often portray themselves as the "Great Silencers," who had to endure what they had experienced in silence.

But in reality, silence was selective only in the case of the Holocaust.

Rather, the fact that they had escaped death made most people enjoy an unprecedentedly hot 'joy of life'.

Within a fortnight of the surrender, movie theaters reopened amidst the ruins, and within two months, dance halls were open enough to accommodate all-night tours.

In Cologne, where only about 5% of the post-war population survived, a small 'carnival procession' was already taking place among the eerie rubble in 1946, while in Berlin the 'Fantasy Ball' took place the same year.

By 1947, people were already going on vacation to resorts.

Of the 10,000 or so holiday homes on Sylt, 6,000 were occupied by refugees, while the rest were occupied by holidaymakers.

The author argues that in the decades immediately following the collapse, there was no widespread social debate about the massacre of millions of people.

The liquidation of the past only began with the Auschwitz trials, which took place from 1963 to 1968.

This too was not so much a product of thorough self-reflection as a historic victory over the parental generation, sparked by the anger of the '68 generation, like the leaflets plastered on the streets in 1967 that read, "Let's launch a movement of disobedience against the Nazi generation."

In other words, the German settlement of its past, which we cite as an example, was the aftereffect of the oppression that the German people inflicted on themselves after 1945.

“Moral collapse and distortion of collective awareness”

An Autopsy of the Post-War German Mentality Through an Insider's Eyes

Naturally, the war completely shook many social concepts in Germany.

The most representative example is ‘moral concept’.

The 'honesty' that we often think of as a characteristic of Germans today was not applicable to post-war Germans.

Germans, who had not known what starvation was until their defeat, felt the 'fear of death' for the first time after the war when their supply chain was destroyed and the Allies drastically reduced food rations.

To survive, the Germans had to learn new survival skills: pillaging, black market trading, and petty theft.

During the 'power vacuum' after the defeat and just before the Allied occupation, the Germans were obsessed with 'plunder'.

Amidst extreme anxiety about what might happen next, people frantically ransacked government buildings, stockpiles, freight trains, farms, and even neighbors' homes.

This was so common that the diary of an ordinary 18-year-old German woman recorded a plundering expedition she went on with her friends and neighbors.

The Allied forces soon stabilized the social system by normalizing administrative institutions, but the moral collapse showed no signs of stopping.

Especially for the three years immediately following the end of the war, Germans were constantly suffering from hunger because they were only given a minimum of 800 calories per person.

People resorted to a variety of generally immoral means of self-preservation, including a 'thieving tour' to the countryside.

City dwellers, unable to buy what they wanted no matter how much money they had, boarded trains to steal the crops of rural farmers.

A hole soon appeared in the gap between the food ration cards.

The black market was overflowing with goods embezzled or smuggled from Allied PXs, and forged food ration cards were circulating in large quantities.

People of this period spoke of the arrival of the 'hour of the wolf', the time when 'humans in their natural state are wolves to other humans'.

It meant that a complete collapse of legal consciousness and moral sentiment was imminent.

“Everyone who didn’t freeze to death stole.

If everyone is a thief, can we really accuse each other of being thieves?”_Page 261

In 1947, criminologist Hans von Hentig published an article expressing concern about the “normalization of crime,” stating that “the scale and form of crime in Germany is unprecedented in the history of Western civilization.”

Countless debates about the Germans' loss of legal consciousness and sense of guilt can be found in magazines, academic books, newspapers, and memoirs of the time.

But if we look at this debate from a historical distance, away from the specifics of post-war German daily life, the debate itself seems absurd.

The fact that in Germany alone 500,000 Jews were looted or driven from their homes, and 165,000 of them murdered, is not mentioned at all in the search for reasons for the disappearance of the legal consciousness.

Even after the defeat, when the world had long since stigmatized the "Germans" as perpetrators of war crimes and genocide, Germans still believed that their country possessed order and dignity.

While the post-war collapse of the system was viewed abroad as an opportunity to resocialize Germany, the fact that Germans now feared that they had fallen into a pit of crime shows how severe the distortion of collective perception was at the time.

The Whereabouts of Jews in Concentration Camps and the Social Role of Wartime Emigrants

This is how the foundation of civil society was laid.

While the Germans enjoyed a dubious happiness amidst their poverty, the repatriation of 8 to 10 million forced laborers also began.

They were 7 million foreigners and Jews who were brought in to solve the labor shortage during the war.

Although 107,000 Jews were transported home each day, many chose to remain in the camps.

The reasons why Jews remained in the camps varied.

Most of them had nowhere to return to, and many were unable to endure the transfer due to mental or physical weakness.

The US military established new camps for Jewish survivors, most notably the Förrenwald concentration camp near Munich, on the grounds that "Jews suffered far more at the hands of the Nazis than did other non-Jewish populations of the same nationality."

Originally a housing complex for a dye company, Förrenwald was more like a concentration camp than a small Jewish community.

It had 15 streets, including Kentucky Street and New York Street, and had its own administrative body, political party, police force, courts, hospital, staff training center, school, theater, sports club, and even a newspaper in Yiddish.

When Israel was established in 1948, many Jews left, but others returned.

These were people who had not been able to adapt to a free life after living in a concentration camp for over a decade, and who longed for the 'passive life' in the concentration camp where others took care of their lives and protected them.

In addition to these forced conscripts, the total number of people for whom the Allied Powers had to take responsibility after the war exceeded 40 million.

Immediately after the war, Germany was entangled in another diaspora: refugees, the homeless, deserters, displaced persons forcibly relocated when eastern Germany became Polish territory after the Yalta and Potsdam conferences, and Jewish refugees flooding into Germany due to anti-Semitism and genocide.

In addition, racism, regionalism, and tribalism were still rampant, and even people at the time could not have imagined that social integration would be possible.

And yet, the ‘miracle of unification’ happened.

The most important role was played by the 12 million displaced people.

Moved to the countryside under the Allied plan, they served as a catalyst for social modernization despite the hostility of the local indigenous population.

Displaced people also played a role in the enzymatic function of delocalization, the leveling of regional differences, the driving force of the economic miracle, and the unification around a national identity rooted in constitutional patriotism.

Institutional integration soon followed.

In particular, the Burden Adjustment Act, implemented in West Germany in 1952, served more than its original purpose of requiring owners of real estate, houses, and other assets to transfer 50% of their value to those who suffered losses.

The foundation of what would later become known as "civil society" was laid in the redistribution process, where a compromise was reached after fierce and persistent debate.

How were the traces of Nazism, fascism, and the Third Reich erased?

The meticulous planning of the Great Designer Alliance

The Allied Forces were responsible for shaking off the taint of fascism during the transition from the Third Reich to a new democratic republic.

The moment the Allies crossed the German Empire's borders, they already had an elaborate plan in their pocket for managing the conquered territories.

'How can we drive the arrogance out of the Germans?' 'How can we rid their brains of the racism that has been instilled in them over the past twelve years?' As a broad plan to capture the German spirit, the Soviet Union first joined hands with German exile groups such as the 'Ulbricht Group' and took over leaflets, radio speeches, and press agencies one by one.

Some of Ulbricht's group managed to find a usable printer and typewriter in the corpse-strewn press quarters.

How quickly all this happened is evident in the fact that on May 22, just two weeks after the defeat, the first issue of the daily newspaper Berliner Zeitung was published with a circulation of 100,000 copies.

The US military also founded and distributed sixteen new newspapers, with the "Ritchie Boys" receiving advanced training at Camp Ritchie in Maryland.

But unlike the Soviet Union, there was another thing the United States focused on in order to 're-educate' the Germans as a 'promoter of democracy'.

It was art, and specifically, abstract art.

The United States believed that abstract art was not only a good aesthetic program for the "denazification of the imagination," but also a suitable means for opposing the Soviet Union and establishing a separate aesthetic identity for West Germany.

American support for abstract art was comprehensive.

He provided subsidies to young artists, funded exhibitions, and purchased large quantities of their work.

Through sophisticated American operations, lyrical abstraction penetrated even the homes of Germans who still harbored aversion to abstract art.

Abstract patterned curtains, carpets, and tablecloths decorate the interior of the house.

Post-war German homes were soon filled with round, bulbous, curved, and slanted small objects and lightweight furniture such as the "kidney-shaped" kidney table.

Heavy oak furniture, a symbol of fascism, was discarded and a new 'zeitgeist' was placed throughout the house.

It may seem absurd to those who believe that reason is the only effective means of denazification, but as the saying goes, “design determines consciousness,” Germans began to overcome the past and move into the future by changing their environment.

What the author wanted to clarify through this book is clear.

'How could it be possible to escape the psychological state that made the Nazi regime possible, despite the fact that many Germans refused to take personal responsibility?' Here, as crucial as the previous delusions of grandeur, a sudden 'awakening to reality', as if from a dream, played a crucial role.

Moreover, the allure of the laid-back lifestyle that came with the Allies, the bitter process of socialization through the black market, the efforts to integrate displaced people, the heated debates surrounding abstract art, and the excitement of new designs also played a significant role.

All of this fostered a change in the psychological state, and on that basis, political discourse on democracy was able to gradually bear fruit.

This is how those whom we call 'Germany' and 'Germans' today were born.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 24, 2024

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 540 pages | 902g | 140*210*32mm

- ISBN13: 9791171710980

- ISBN10: 1171710984

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)