collaborator

|

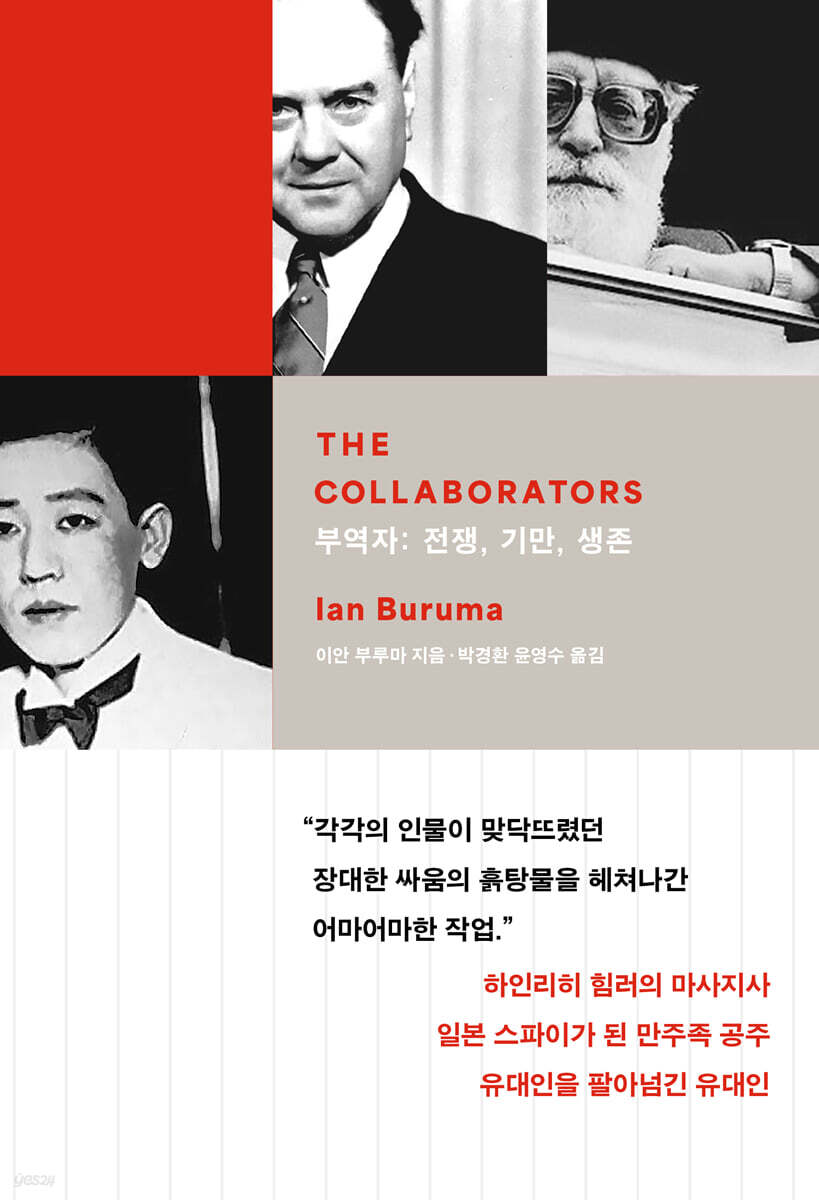

Description

Book Introduction

World War II, trace the lives of those who helped those in power!

This book is a testament to the power and credibility of history.

Kersten, Heinrich Himmler's indispensable personal masseuse

Yoshiko, a Manchurian princess who became a spy for the Japanese secret police in China

Weinreff, a Dutch Hasidic Jew who sold out fellow Jews to the German secret police

We will weigh the weight of good and evil and measure the weight of morality.

Here are three extraordinary people.

Felix Kersten, a masseuse with a good physique and a happy life.

Aisin Jueluo Xianyu (Kawashima Yoshiko), a Qing princess with a small build who dresses up as a man.

Weinref, a Jew who extorted money from Jews destined for extermination camps in exchange for their lives.

This book is a kind of biography that traces the lives of three people who lived through World War II in a unique way.

The three are known in German as 'Hochstapler'.

Hochstaffler, whose name translates to swindler, braggart, or charlatan, does not fit neatly into the categories of collaborator or resister, but lives a contradictory life that provokes strong moral condemnation while still making one tilt one's head.

The author suggests that we reread history through these.

This will allow us to measure the weight of morality more precisely, to weigh the proportions of good and evil within each person, and to acknowledge that fiction is as important as fact in history.

Why did the author choose these three? Acts of service and resistance during wartime don't fit neatly into the moral narrative of good and evil.

Evil things can be done with good intentions, and evil people can sometimes do good things.

For example, Kersten cared for the body and mind of Himmler, who planned to murder Jews, but later helped rescue Jews.

None of the three were completely corrupt, a trait that is common among those active in the public sphere today.

The author suggests that it is easier to imagine ourselves as sinners rather than adults, and that we reflect on the issue of forced labor by putting ourselves in these three categories.

History is not simple.

This book unfolds the complexity of life and the multifaceted nature of ethics in the broadest possible way.

There are inflection points there.

Either become a moral person or conform to the system.

The book unfolds in a way that the journeys of three people unfold simultaneously in Germany, the Netherlands, China, and Japan.

A mixture of traitors, collaborators, spies, and witnesses, these characters have crossed borders and shaken up history quite a bit.

What is required of readers is not to be swayed by fake news or testimonies, but to use their historical perspective and ability to discern facts to select trustworthy testimony, not to fall for deception born of desperation, and to have human understanding but not to be consistently ethically lax.

This book is a testament to the power and credibility of history.

Kersten, Heinrich Himmler's indispensable personal masseuse

Yoshiko, a Manchurian princess who became a spy for the Japanese secret police in China

Weinreff, a Dutch Hasidic Jew who sold out fellow Jews to the German secret police

We will weigh the weight of good and evil and measure the weight of morality.

Here are three extraordinary people.

Felix Kersten, a masseuse with a good physique and a happy life.

Aisin Jueluo Xianyu (Kawashima Yoshiko), a Qing princess with a small build who dresses up as a man.

Weinref, a Jew who extorted money from Jews destined for extermination camps in exchange for their lives.

This book is a kind of biography that traces the lives of three people who lived through World War II in a unique way.

The three are known in German as 'Hochstapler'.

Hochstaffler, whose name translates to swindler, braggart, or charlatan, does not fit neatly into the categories of collaborator or resister, but lives a contradictory life that provokes strong moral condemnation while still making one tilt one's head.

The author suggests that we reread history through these.

This will allow us to measure the weight of morality more precisely, to weigh the proportions of good and evil within each person, and to acknowledge that fiction is as important as fact in history.

Why did the author choose these three? Acts of service and resistance during wartime don't fit neatly into the moral narrative of good and evil.

Evil things can be done with good intentions, and evil people can sometimes do good things.

For example, Kersten cared for the body and mind of Himmler, who planned to murder Jews, but later helped rescue Jews.

None of the three were completely corrupt, a trait that is common among those active in the public sphere today.

The author suggests that it is easier to imagine ourselves as sinners rather than adults, and that we reflect on the issue of forced labor by putting ourselves in these three categories.

History is not simple.

This book unfolds the complexity of life and the multifaceted nature of ethics in the broadest possible way.

There are inflection points there.

Either become a moral person or conform to the system.

The book unfolds in a way that the journeys of three people unfold simultaneously in Germany, the Netherlands, China, and Japan.

A mixture of traitors, collaborators, spies, and witnesses, these characters have crossed borders and shaken up history quite a bit.

What is required of readers is not to be swayed by fake news or testimonies, but to use their historical perspective and ability to discern facts to select trustworthy testimony, not to fall for deception born of desperation, and to have human understanding but not to be consistently ethically lax.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

prolog

Chapter 1: Paradise Lost

Chapter 2: Foreign Countries

Chapter 3: Miracles

Chapter 4: Cheap and False Time

Chapter 5: Crossing the Line

Chapter 6: A Beautiful Story

Chapter 7: The Hunting Party

Chapter 8: Endgame

Chapter 9: The End

Chapter 10: Aftermath

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

main

Search

Chapter 1: Paradise Lost

Chapter 2: Foreign Countries

Chapter 3: Miracles

Chapter 4: Cheap and False Time

Chapter 5: Crossing the Line

Chapter 6: A Beautiful Story

Chapter 7: The Hunting Party

Chapter 8: Endgame

Chapter 9: The End

Chapter 10: Aftermath

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

main

Search

Into the book

No country has as many theories and as unclear an attitude toward the truth of war as Japan.

In Japanese films, musicals, comics, novels, and history books, Yoshiko Kawashima is portrayed as a tragic figure who deserves no blame.

Like the experience of being bullied, guilt can also give rise to countless myths.

--- p.12~13

I chose these three men as protagonists not because they are typical examples of collaborators, but because they are people who reinvented themselves in a time of war, persecution, and genocide.

It was a time when moral choices could easily have fatal consequences, but it was also a time when what was moral was not as clear as we were taught to believe later, when all threats had passed.

--- p.19

If there is anyone who can be said to have been caught up in the turbulent currents of history and become a pawn of fate, it is my distant cousin, Fritz Cormis.

In my memory, he was a pale, haggard man with a thick German accent, who spoke cynically about the twists and turns of life.

Fritz was a sculptor.

(…) He was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army and fought on the Eastern Front.

Wounded and captured by the Russian army, Fritz endured a grueling time in a Siberian prisoner-of-war camp.

He once told me about his harrowing experience: “If you live in your underwear, you learn a lot about the people around you.”

Fritz managed to escape by obtaining a fake Swiss passport.

(…) They immigrated to the Netherlands.

I didn't stay in the Netherlands very long.

Fritz felt that the Dutch were naively and complacently considering the consequences of Hitler's rise in neighboring Germany.

--- p.119

Absolute power over the powerless does not always lead to criminal abuse.

People who want to do good sometimes end up saving the lives of others.

A German lawyer named Hans Georg Kalmayer was in charge of the "Jewish Question" for the occupying government.

The question of whether someone was a pure Jew or a half-Jew was entirely up to him, and this meant life or death.

Kalmayer appears to have turned a blind eye to numerous documents that were clearly false.

But in other cases, he also faithfully performed his administrative duties and sent Jews to exile.

Many people still consider him a hero.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, honors Kalmayer as a "Righteous Man among the Nations."

But he was also a vital cog in a machine that perpetrated organized murder.

Bainref was not that kind of cogwheel.

His power to control the fate of others was purely a product of fantasy.

--- p.160~161

Like all people with unlimited power over others, Gameker had a fickle side.

But his whims were ones befitting the Nazis' characteristic pretensions to mass murder.

Gameker was a man who showed his love for children.

There was a newborn baby named Maciel.

Maciel barely managed to survive when his mother was forced to leave him behind in a cattle stall.

Gemecker asked a renowned Jewish pediatrician named Simon Pancrevelt to do whatever it took to save the baby.

An incubator was specially procured in Groningen.

The gamemaker visited the child every day to check on his condition.

He even offered his finest Hennessy brandy for a medical prescription devised by Dr. Pancrevelt.

Finally, as everyone hoped, the baby began to regain his strength.

When Maciel reached 6 pounds (about 2.72 kilograms), Gameker decided it was time to put him to work.

And then they sent them to Auschwitz by transport.

As I read Maciel's story, I thought the name Pancrevelt sounded familiar.

And soon, as I realized that he was a close friend and fellow pediatrician of my grandfather, I couldn't help but feel a chill down my spine at the thought that Maciel's grotesque anecdote was a story all my own.

--- p.283~284

Providing medical care to those targeted for extermination was another Nazi charade present in Westerbork.

--- p.285

Rewriting history is a continuous process.

Most of what people know about the past comes from fictional works such as novels, movies, musicals, and comics.

Myths sometimes bypass history entirely, for example by claiming that nothing ever ended or that heroes never died.

Speaking of this, the story of the resurrection of Jesus Christ comes to mind, but Jesus' death has never been denied.

Jesus came back to life like a tree sprouting new buds after a dry winter.

The story of Jesus is less a myth and more a parable about the cycle of life and death.

In Japanese films, musicals, comics, novels, and history books, Yoshiko Kawashima is portrayed as a tragic figure who deserves no blame.

Like the experience of being bullied, guilt can also give rise to countless myths.

--- p.12~13

I chose these three men as protagonists not because they are typical examples of collaborators, but because they are people who reinvented themselves in a time of war, persecution, and genocide.

It was a time when moral choices could easily have fatal consequences, but it was also a time when what was moral was not as clear as we were taught to believe later, when all threats had passed.

--- p.19

If there is anyone who can be said to have been caught up in the turbulent currents of history and become a pawn of fate, it is my distant cousin, Fritz Cormis.

In my memory, he was a pale, haggard man with a thick German accent, who spoke cynically about the twists and turns of life.

Fritz was a sculptor.

(…) He was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army and fought on the Eastern Front.

Wounded and captured by the Russian army, Fritz endured a grueling time in a Siberian prisoner-of-war camp.

He once told me about his harrowing experience: “If you live in your underwear, you learn a lot about the people around you.”

Fritz managed to escape by obtaining a fake Swiss passport.

(…) They immigrated to the Netherlands.

I didn't stay in the Netherlands very long.

Fritz felt that the Dutch were naively and complacently considering the consequences of Hitler's rise in neighboring Germany.

--- p.119

Absolute power over the powerless does not always lead to criminal abuse.

People who want to do good sometimes end up saving the lives of others.

A German lawyer named Hans Georg Kalmayer was in charge of the "Jewish Question" for the occupying government.

The question of whether someone was a pure Jew or a half-Jew was entirely up to him, and this meant life or death.

Kalmayer appears to have turned a blind eye to numerous documents that were clearly false.

But in other cases, he also faithfully performed his administrative duties and sent Jews to exile.

Many people still consider him a hero.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, honors Kalmayer as a "Righteous Man among the Nations."

But he was also a vital cog in a machine that perpetrated organized murder.

Bainref was not that kind of cogwheel.

His power to control the fate of others was purely a product of fantasy.

--- p.160~161

Like all people with unlimited power over others, Gameker had a fickle side.

But his whims were ones befitting the Nazis' characteristic pretensions to mass murder.

Gameker was a man who showed his love for children.

There was a newborn baby named Maciel.

Maciel barely managed to survive when his mother was forced to leave him behind in a cattle stall.

Gemecker asked a renowned Jewish pediatrician named Simon Pancrevelt to do whatever it took to save the baby.

An incubator was specially procured in Groningen.

The gamemaker visited the child every day to check on his condition.

He even offered his finest Hennessy brandy for a medical prescription devised by Dr. Pancrevelt.

Finally, as everyone hoped, the baby began to regain his strength.

When Maciel reached 6 pounds (about 2.72 kilograms), Gameker decided it was time to put him to work.

And then they sent them to Auschwitz by transport.

As I read Maciel's story, I thought the name Pancrevelt sounded familiar.

And soon, as I realized that he was a close friend and fellow pediatrician of my grandfather, I couldn't help but feel a chill down my spine at the thought that Maciel's grotesque anecdote was a story all my own.

--- p.283~284

Providing medical care to those targeted for extermination was another Nazi charade present in Westerbork.

--- p.285

Rewriting history is a continuous process.

Most of what people know about the past comes from fictional works such as novels, movies, musicals, and comics.

Myths sometimes bypass history entirely, for example by claiming that nothing ever ended or that heroes never died.

Speaking of this, the story of the resurrection of Jesus Christ comes to mind, but Jesus' death has never been denied.

Jesus came back to life like a tree sprouting new buds after a dry winter.

The story of Jesus is less a myth and more a parable about the cycle of life and death.

--- p.384

Publisher's Review

Kersten: Was he a Nazi who helped the Nazi leader?

Felix Kersten.

He was the personal masseuse of Himmler, head of the Nazi SS.

In other words, he used both hands to care for the body and mind of Himmler, who committed genocide.

Like barbers or court jesters, masseuses can become confidants of those in power.

People in power often suffer from psychological stress-related ailments such as chronic headaches, insomnia, and stomach cramps, and massage therapists can help alleviate their suffering.

Kersten himself said, “Through my practice, I gained the trust of those in leadership positions.”

He was a man who willingly adapted to the Nazi regime and “absorbed happiness.”

However, as Germany's defeat became apparent towards the end of the war, Kersten changed sides to seek a way out.

In other words, he saved thousands of Jews from the concentration camps, even at the risk of his own life.

Some have claimed that he did this for the sake of making money, but the author says that even if that were true, it cannot be said that he was devoid of any human decency.

He knew that his title as Himmler's masseuse would be threatened after the war, so he moved to help Jews, even making a risky attempt to persuade Himmler to release other prisoners.

In other words, Kersten was not the type of person who would enslave people and leave them to die in terrible conditions.

How should we evaluate Kersten, who has such ambivalence? The author argues, "Massaging the Nazi leader doesn't necessarily make him a war criminal, but he was undoubtedly a Nazi collaborator."

He was not a Nazi (he had no interest in politics).

But he was a god who served that class of people.

Even if that class was not all Nazis, they were people who adapted well to Hitler's empire.

Businessmen and entrepreneurs, professors and doctors, diplomats and bureaucrats.

Just as they had served effectively in postwar democratic societies, Kersten never severed ties with his colleagues from the Hitler era, even though he reversed his position after the war.

I still used to give them massages and rely on their money or power.

Therefore, the weight and nature of his good and evil can vary depending on our detailed moral consciousness and evaluation.

Yoshiko: A spy fragmented into pieces

During the period when Kersten was enjoying a comfortable life through his connections under the Nazis, a person named Yoshiko was talked about in the East.

Yoshiko's life is the most dramatic of all the characters covered in this book.

That means living the most twisted life, but at the same time, living like an actor in a play.

She was a Manchurian princess, and her life was spent traveling between Japan and China when her father gave her up to a Japanese family as an adopted daughter.

Yoshiko was a cross-dresser who had relationships with both men and women, which made headlines.

He engaged in espionage while maintaining a perverted relationship with Japanese Army officer Ryukichi Tanaka, and had a Japanese woman named Chizuko serve him, calling her “my beautiful wife.”

Moreover, she had a habit of going from one extreme to the other, from calling the Japanese thugs and their failed policies to praising their heroic efforts to build a new Asia.

One of her performances involved preaching racial harmony in Manchukuo while dressed in a Chinese men's long robe or a Japanese women's kimono.

And the performance promoted Japan's belligerent strategies under the pretext of Sino-Japanese friendship.

Yoshiko had a mixture of disparate aspects.

Her personality was a mixture of fragments: a Manchurian aristocrat, the far-right figures who surrounded her father and adoptive father, several Japanese lovers in positions of power, and her own rich imagination.

Court, October 5, 1947.

As 5,000 eyes watched Yoshiko, a list of her alleged crimes was laid out.

The crime of organizing a private army to conquer Chinese territory in Manchuria, the crime of helping to place Puyi on the throne of a puppet state, the crime of plotting an invasion of China, the crime of helping to instigate the Shanghai Incident, the crime of stealing Chinese military secrets, the crime of spreading Japanese propaganda, the crime of attempting to restore the Qing Dynasty, the crime of betraying the motherland by supporting Chinese collaborators, the crime of acting like a male military hero while being infected by the "samurai spirit" of the Japanese militarists...

But what was more surprising than the allegations was the evidence supporting them.

She was a spy who betrayed her country, but at the same time she was a victim of baseless accusations.

The flamboyant character Yoshiko had a delusional disorder, and her life has been dramatized in many novels and films, so the court included Yoshiko's actions in those works among a list of real-life crimes.

In other words, the lies she had told at the end of her life consumed Yoshiko herself.

The thirty-three-year-old was locked in solitary confinement in a prison cell, her head shaved and her upper teeth knocked out.

And even until the moment of his death, he was telling stories.

Weinreff: Stopping the Auschwitz Train by Selling Jews

Bainlev was Jewish.

However, his position in Jewish society was ambiguous: although he belonged to a poor Jewish immigrant family, he considered himself culturally sophisticated, and, unlike other Jews, he identified more with German Jews and had a sense of superiority.

He is the one who sold out Jews to the Nazis for money.

Wealthy Jews desperately tried to survive by putting their names on the rescue list, believing only in Bainlev.

In fact, he once manipulated the Westerbork camp commander, Gemecker, into stopping a train to Auschwitz, which was a remarkable feat.

But that was all.

The very existence of Bainref was a long list of lies.

There were so many Jews he sold out after pocketing their money that it took a tremendous amount of time and manpower to compile the testimonies about him after the war.

After a thorough review of the testimony of over 600 witnesses over six years, the culled report totaled 1,683 pages.

The author asks, closely analyzing materials from the Netherlands National Exhibition Documentation Institute.

“Will you believe Weinreff’s account, or will you believe most people’s accounts except Weinreff?” In other words, the book encourages the reader to make a judgment about whose testimony in history and how much to trust.

Weinreff undoubtedly saved the Jews, but he lied too much and took too much money, and eventually those Jews were sent to the concentration camps.

However, the author also leaves a comment that he was “a sharp observer of one’s own state of mind, and there was some truth in it.”

The conclusions drawn by post-war investigators about Bainlev were devastating.

'Weinreb betrayed Jews and collaborated with the SD, the Nazi SS security service.' He also wrote several books in which he defended himself vigorously.

He died in Switzerland in 1988, and was revered by a number of people who sought spiritual comfort from him until his death.

The story of our lives is shaped over time.

Fraud, forgery, and lies are inevitable products of war.

In an occupied country, people must hide their real names and resort to deception to operate, and even in the occupied country, conspiracy theories and imaginations are bound to run rampant.

In addition to the people introduced in this book, many others have committed acts of aiding others for their own reasons.

However, the author says that the harshest reprisals were meted out to some who committed the least serious acts of collaborating after the war.

These are women who slept with the enemy.

These women engaged with the enemy for reasons such as comfort, desire, loneliness, and (perhaps) love, but rarely out of profound ideological commitment.

But the crowd shaved the women's heads, covered them in excrement, spat on them, and even raped them.

Unlike corrupt officials, doctors and politicians with problematic pasts who have become the new elite or upper class without any problems.

The three translators of this book did not live in truth, but extended their lives in fiction.

The author says that this may have been due to emotions such as fear or arrogance, or it may have been done for no particular reason.

The three assistants had slightly different conclusions.

Bainref and Yoshiko saw through the lies life presented to them in their own way, and also showed the courage to tell the truth.

Kersten, looking back on his life, also claimed that he was like that.

However, the author shows a little more understanding and generosity to the first two people.

Because Kersten was more compliant with the system.

History is not an exact science.

We can figure out what actually happened, but the rest is all in the realm of interpretation.

Human memory is changeable, easily manipulated, and can be wrong at any time.

Much of the story of our past lives is embellished over time, and our thoughts change.

The author says that the only way to glimpse the truth, even briefly, is to question our own thinking.

“The dogmatic assertion that there is only one truth is not only oppressive but also downright wrong.

“If we do not allow ourselves to doubt any ideology we believe in, we are living in a lie.”

Felix Kersten.

He was the personal masseuse of Himmler, head of the Nazi SS.

In other words, he used both hands to care for the body and mind of Himmler, who committed genocide.

Like barbers or court jesters, masseuses can become confidants of those in power.

People in power often suffer from psychological stress-related ailments such as chronic headaches, insomnia, and stomach cramps, and massage therapists can help alleviate their suffering.

Kersten himself said, “Through my practice, I gained the trust of those in leadership positions.”

He was a man who willingly adapted to the Nazi regime and “absorbed happiness.”

However, as Germany's defeat became apparent towards the end of the war, Kersten changed sides to seek a way out.

In other words, he saved thousands of Jews from the concentration camps, even at the risk of his own life.

Some have claimed that he did this for the sake of making money, but the author says that even if that were true, it cannot be said that he was devoid of any human decency.

He knew that his title as Himmler's masseuse would be threatened after the war, so he moved to help Jews, even making a risky attempt to persuade Himmler to release other prisoners.

In other words, Kersten was not the type of person who would enslave people and leave them to die in terrible conditions.

How should we evaluate Kersten, who has such ambivalence? The author argues, "Massaging the Nazi leader doesn't necessarily make him a war criminal, but he was undoubtedly a Nazi collaborator."

He was not a Nazi (he had no interest in politics).

But he was a god who served that class of people.

Even if that class was not all Nazis, they were people who adapted well to Hitler's empire.

Businessmen and entrepreneurs, professors and doctors, diplomats and bureaucrats.

Just as they had served effectively in postwar democratic societies, Kersten never severed ties with his colleagues from the Hitler era, even though he reversed his position after the war.

I still used to give them massages and rely on their money or power.

Therefore, the weight and nature of his good and evil can vary depending on our detailed moral consciousness and evaluation.

Yoshiko: A spy fragmented into pieces

During the period when Kersten was enjoying a comfortable life through his connections under the Nazis, a person named Yoshiko was talked about in the East.

Yoshiko's life is the most dramatic of all the characters covered in this book.

That means living the most twisted life, but at the same time, living like an actor in a play.

She was a Manchurian princess, and her life was spent traveling between Japan and China when her father gave her up to a Japanese family as an adopted daughter.

Yoshiko was a cross-dresser who had relationships with both men and women, which made headlines.

He engaged in espionage while maintaining a perverted relationship with Japanese Army officer Ryukichi Tanaka, and had a Japanese woman named Chizuko serve him, calling her “my beautiful wife.”

Moreover, she had a habit of going from one extreme to the other, from calling the Japanese thugs and their failed policies to praising their heroic efforts to build a new Asia.

One of her performances involved preaching racial harmony in Manchukuo while dressed in a Chinese men's long robe or a Japanese women's kimono.

And the performance promoted Japan's belligerent strategies under the pretext of Sino-Japanese friendship.

Yoshiko had a mixture of disparate aspects.

Her personality was a mixture of fragments: a Manchurian aristocrat, the far-right figures who surrounded her father and adoptive father, several Japanese lovers in positions of power, and her own rich imagination.

Court, October 5, 1947.

As 5,000 eyes watched Yoshiko, a list of her alleged crimes was laid out.

The crime of organizing a private army to conquer Chinese territory in Manchuria, the crime of helping to place Puyi on the throne of a puppet state, the crime of plotting an invasion of China, the crime of helping to instigate the Shanghai Incident, the crime of stealing Chinese military secrets, the crime of spreading Japanese propaganda, the crime of attempting to restore the Qing Dynasty, the crime of betraying the motherland by supporting Chinese collaborators, the crime of acting like a male military hero while being infected by the "samurai spirit" of the Japanese militarists...

But what was more surprising than the allegations was the evidence supporting them.

She was a spy who betrayed her country, but at the same time she was a victim of baseless accusations.

The flamboyant character Yoshiko had a delusional disorder, and her life has been dramatized in many novels and films, so the court included Yoshiko's actions in those works among a list of real-life crimes.

In other words, the lies she had told at the end of her life consumed Yoshiko herself.

The thirty-three-year-old was locked in solitary confinement in a prison cell, her head shaved and her upper teeth knocked out.

And even until the moment of his death, he was telling stories.

Weinreff: Stopping the Auschwitz Train by Selling Jews

Bainlev was Jewish.

However, his position in Jewish society was ambiguous: although he belonged to a poor Jewish immigrant family, he considered himself culturally sophisticated, and, unlike other Jews, he identified more with German Jews and had a sense of superiority.

He is the one who sold out Jews to the Nazis for money.

Wealthy Jews desperately tried to survive by putting their names on the rescue list, believing only in Bainlev.

In fact, he once manipulated the Westerbork camp commander, Gemecker, into stopping a train to Auschwitz, which was a remarkable feat.

But that was all.

The very existence of Bainref was a long list of lies.

There were so many Jews he sold out after pocketing their money that it took a tremendous amount of time and manpower to compile the testimonies about him after the war.

After a thorough review of the testimony of over 600 witnesses over six years, the culled report totaled 1,683 pages.

The author asks, closely analyzing materials from the Netherlands National Exhibition Documentation Institute.

“Will you believe Weinreff’s account, or will you believe most people’s accounts except Weinreff?” In other words, the book encourages the reader to make a judgment about whose testimony in history and how much to trust.

Weinreff undoubtedly saved the Jews, but he lied too much and took too much money, and eventually those Jews were sent to the concentration camps.

However, the author also leaves a comment that he was “a sharp observer of one’s own state of mind, and there was some truth in it.”

The conclusions drawn by post-war investigators about Bainlev were devastating.

'Weinreb betrayed Jews and collaborated with the SD, the Nazi SS security service.' He also wrote several books in which he defended himself vigorously.

He died in Switzerland in 1988, and was revered by a number of people who sought spiritual comfort from him until his death.

The story of our lives is shaped over time.

Fraud, forgery, and lies are inevitable products of war.

In an occupied country, people must hide their real names and resort to deception to operate, and even in the occupied country, conspiracy theories and imaginations are bound to run rampant.

In addition to the people introduced in this book, many others have committed acts of aiding others for their own reasons.

However, the author says that the harshest reprisals were meted out to some who committed the least serious acts of collaborating after the war.

These are women who slept with the enemy.

These women engaged with the enemy for reasons such as comfort, desire, loneliness, and (perhaps) love, but rarely out of profound ideological commitment.

But the crowd shaved the women's heads, covered them in excrement, spat on them, and even raped them.

Unlike corrupt officials, doctors and politicians with problematic pasts who have become the new elite or upper class without any problems.

The three translators of this book did not live in truth, but extended their lives in fiction.

The author says that this may have been due to emotions such as fear or arrogance, or it may have been done for no particular reason.

The three assistants had slightly different conclusions.

Bainref and Yoshiko saw through the lies life presented to them in their own way, and also showed the courage to tell the truth.

Kersten, looking back on his life, also claimed that he was like that.

However, the author shows a little more understanding and generosity to the first two people.

Because Kersten was more compliant with the system.

History is not an exact science.

We can figure out what actually happened, but the rest is all in the realm of interpretation.

Human memory is changeable, easily manipulated, and can be wrong at any time.

Much of the story of our past lives is embellished over time, and our thoughts change.

The author says that the only way to glimpse the truth, even briefly, is to question our own thinking.

“The dogmatic assertion that there is only one truth is not only oppressive but also downright wrong.

“If we do not allow ourselves to doubt any ideology we believe in, we are living in a lie.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 3, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 464 pages | 678g | 140*205*28mm

- ISBN13: 9791169091169

- ISBN10: 1169091164

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)