Defense for the Disqualified

|

Description

Book Introduction

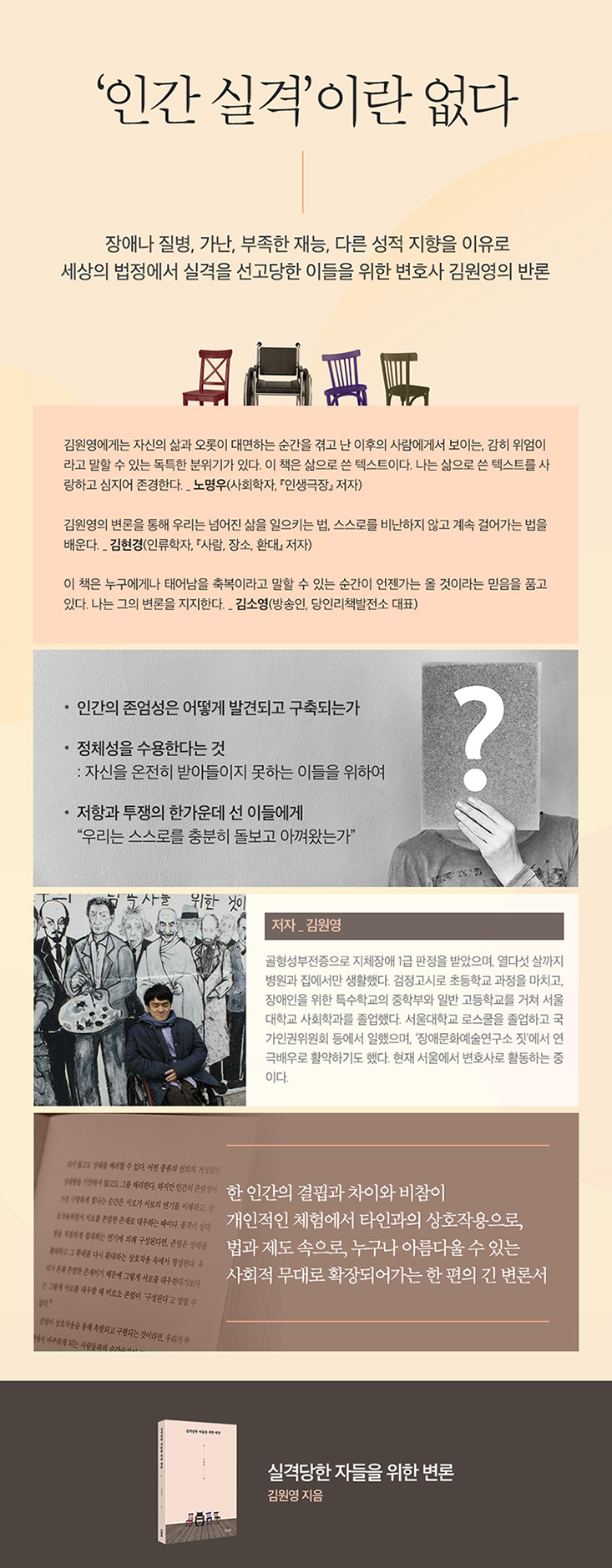

There is no such thing as 'disqualification from being human'

Is there a life where being born into this world is a loss in itself? A lifelong disability that confines you to your room, abject poverty that makes it difficult to feed your children, an unattractive appearance that no one likes, or a different sexual orientation…

If living a life of marginalization, exclusion, and self-deprecation, while embracing such a minority status, wouldn't it be better to never have been born? The "Wrongful Life Lawsuit," a central motif of this book, is a type of civil lawsuit in which a child born with a disability seeks damages from a doctor who failed to diagnose the disability, claiming it would have been better for the child not to have been born.

This lawsuit raises the difficult question of whether being born can be more damaging than not being born.

Kim Won-young, a lawyer with a first-degree physical disability, had to struggle with this question throughout his formative years.

Born into a poor family with a body that could not walk, he had to constantly ask himself whether his existence was a loss to his parents, society, and even himself.

In this book, he attempts to argue that those who, like himself, are often called "wrong lives" or "disqualified lives" have dignity and charm in their very existence.

His argument begins by exploring how respect for humanity emerges from everyday interactions between people.

Afterwards, it presents what it means to decide to accept one's own deficiencies and differences as one's own identity, and seeks a way for the unique stories of individuals who accept their identity and live in that way to enter the gates of law and institutions.

Furthermore, if all beings were given a platform to reveal who they are, with their own characteristics, experiences, preferences, and sufferings, it suggests the prospect that minorities themselves would be able to defend themselves against the stigma of being "disqualified from being human."

Is there a life where being born into this world is a loss in itself? A lifelong disability that confines you to your room, abject poverty that makes it difficult to feed your children, an unattractive appearance that no one likes, or a different sexual orientation…

If living a life of marginalization, exclusion, and self-deprecation, while embracing such a minority status, wouldn't it be better to never have been born? The "Wrongful Life Lawsuit," a central motif of this book, is a type of civil lawsuit in which a child born with a disability seeks damages from a doctor who failed to diagnose the disability, claiming it would have been better for the child not to have been born.

This lawsuit raises the difficult question of whether being born can be more damaging than not being born.

Kim Won-young, a lawyer with a first-degree physical disability, had to struggle with this question throughout his formative years.

Born into a poor family with a body that could not walk, he had to constantly ask himself whether his existence was a loss to his parents, society, and even himself.

In this book, he attempts to argue that those who, like himself, are often called "wrong lives" or "disqualified lives" have dignity and charm in their very existence.

His argument begins by exploring how respect for humanity emerges from everyday interactions between people.

Afterwards, it presents what it means to decide to accept one's own deficiencies and differences as one's own identity, and seeks a way for the unique stories of individuals who accept their identity and live in that way to enter the gates of law and institutions.

Furthermore, if all beings were given a platform to reveal who they are, with their own characteristics, experiences, preferences, and sufferings, it suggests the prospect that minorities themselves would be able to defend themselves against the stigma of being "disqualified from being human."

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Entering_A Wrong Life and a Good Encounter

Chapter 1: Experienced Disabled Persons

1.8 seconds _ Nuclear and the Crippled Legs _ Life as Performance: Symbolized Humans _ The Dilemma of Experience

Chapter 2: A Performance of Dignity and Dignity

The grotesqueness of the highest dignity / A performance that creates dignity _ A performance that constitutes dignity

Chapter 3: We Deny Love and Justice

Blue Grass Society _ Live or Die Theatrically _ Stop being a victim

Chapter 4: The Wrong Life

“You gave birth to me, so compensate for the damage”_ Choosing a child with hearing impairment_ Removing and choosing a disability_ “Then I’ll cut off your leg too”

Chapter 5: Willing Responsibility

Parents and Children _ Faith and Acceptance _ Accepting Disability

Chapter 6 Before the Law

Closed Ward _ Becoming a Mentally Ill Person _ No Way Out _ The Gatekeeper of the Law _ An Integrative Theory Explaining Life _ A Delusional Writer _ Is There a Hierarchy in Self-Narratives _ Reading Comprehension and Becoming a Co-Author

Chapter 7: Inventing Rights

The Right to Piss _ It's Not Your Fault _ Into the Law _ Your Uniqueness is Rightful and Justified

Chapter 8: Equality of Opportunity for Beauty

Politically Correct Love_ _ The Attractiveness Discrimination Act_ I'm Attracted to Your Amputated Body_ 'The Wrong Body' and Beauty_ Portrait Painting_ Distributing Opportunities to Be Beautiful_ Things We Don't Have

Chapter 9: You Don't Have to Be a Monster

Complete Love _ Personal Experience _ Concluding the Argument

Acknowledgements

References

Entering_A Wrong Life and a Good Encounter

Chapter 1: Experienced Disabled Persons

1.8 seconds _ Nuclear and the Crippled Legs _ Life as Performance: Symbolized Humans _ The Dilemma of Experience

Chapter 2: A Performance of Dignity and Dignity

The grotesqueness of the highest dignity / A performance that creates dignity _ A performance that constitutes dignity

Chapter 3: We Deny Love and Justice

Blue Grass Society _ Live or Die Theatrically _ Stop being a victim

Chapter 4: The Wrong Life

“You gave birth to me, so compensate for the damage”_ Choosing a child with hearing impairment_ Removing and choosing a disability_ “Then I’ll cut off your leg too”

Chapter 5: Willing Responsibility

Parents and Children _ Faith and Acceptance _ Accepting Disability

Chapter 6 Before the Law

Closed Ward _ Becoming a Mentally Ill Person _ No Way Out _ The Gatekeeper of the Law _ An Integrative Theory Explaining Life _ A Delusional Writer _ Is There a Hierarchy in Self-Narratives _ Reading Comprehension and Becoming a Co-Author

Chapter 7: Inventing Rights

The Right to Piss _ It's Not Your Fault _ Into the Law _ Your Uniqueness is Rightful and Justified

Chapter 8: Equality of Opportunity for Beauty

Politically Correct Love_ _ The Attractiveness Discrimination Act_ I'm Attracted to Your Amputated Body_ 'The Wrong Body' and Beauty_ Portrait Painting_ Distributing Opportunities to Be Beautiful_ Things We Don't Have

Chapter 9: You Don't Have to Be a Monster

Complete Love _ Personal Experience _ Concluding the Argument

Acknowledgements

References

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

The deficiencies, differences and misery of one human being

From personal experience to interaction with others, to law and institutions,

A long argument expanding into a social arena where anyone can be beautiful.

Won-Young Kim, a first-class disabled person, wrote a book in 2010 declaring that he refused to be a “disabled person who overcame disability,” a symbol of indomitable will and hope, and instead would become a “vulgar” disabled person, a “bad” disabled person.

Based on his personal story of how he, who had been confined to his room until the age of fifteen, went on to attend a school for the disabled and then Seoul National University Law School, he testified to the power of freedom and solidarity of courageous people who enabled minorities like himself to emerge into the world.

He was a young man of twenty-nine at the time, and in the book's epilogue, he said, "I hope to live a life where I can someday defend myself rather than testify, a life where I can tell my story with a little more confidence. That's the kind of life I want to live in my thirties."

Now in his thirties, he is a researcher and lawyer who has decided to go beyond expressing his anger and desires and instead advocate for the lives of those labeled as "wrong" or "disqualified" in our society.

To prevent them from living in pain, either by denying their very birth or by never being able to accept their physical and mental characteristics, I compiled evidence proving that all beings can be dignified and attractive, and wrote a lengthy defense.

How is human dignity discovered and built?

The author begins his discussion by examining the dilemma faced by minorities in the dramatic moments they encounter in their lives: how to deftly confront and gracefully confront discrimination, exclusion, shame, and humiliation.

This attitude of mind, adopted to protect oneself, turns every moment of life into a kind of performance.

Unexpectedly, this bears some resemblance to the theatrical lives of those who have insulted him, those who plan the ceremonies and mobilize the disabled.

However, rather than telling us to throw away false theater, the author borrows from the discussions of sociologist Erving Goffman and anthropologist Kim Hyun-kyung to say that theatrical interactions between people can develop in a way that builds human dignity.

A stage production by one child who stays with his disabled friend while all the other children run to the valley on a hot summer day, saying, “I need to take care of my skin,” and another child who understands his performance and sends his friend off with appropriate words.

Through this 'performance that constitutes dignity,' the author suggests the possibility that an individual who has been enduring pain alone can rise up as a dignified human being through encounters with others.

When my friend says, “You need to take care of your skin,” I know he’s lying because I respect him, so I agree with him.

In my response, he knows that I respect him, and he respects me even more.

When he respects me, I respect myself too.

In the end, I send him off to the valley he really wanted to go to, and he leaves, giving me a comic book and saving my self-esteem.

We acted with a deep understanding that we were each a single entity with desires and pride, and this performance made our existence more dense.

(syncopation)

The moment when human dignity shines most clearly is when people understand each other's performances and treat each other with dignity through interaction.

If character is formed through the performance of treating others appropriately, dignity is formed through the interaction of welcoming others and returning that hospitality.

Rather than saying that we treat each other that way because we are inherently dignified beings, we can say that dignity is 'constituted' only when we treat each other that way.

_ Pages 69-71

Minorities who have confirmed that they are dignified human beings through interactions with parents, siblings, friends, and lovers now go out into the world.

The author, a former lawyer and disability discrimination investigator at the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, points out that, based on his experience as a gatekeeper of the law and encountering those who are discriminated against, laws and systems fail to recognize the unique narratives of each individual, the most fundamental prerequisite for human dignity, in the name of protection, treatment, and welfare.

Whatever their complex and unique life stories, backgrounds, and bodily experiences, the law requires that they self-identify as mentally ill if they want to receive (effective, non-coercive) services.

In order to receive the protection and support of the law, it is a request to completely reduce a person's personality to the 'attributes' or 'background' that are precisely the reason for the protection, that is, to reduce their existence to just the physical and developmental disabilities themselves.

(syncopation)

The Constitution states that individuals have dignity because they possess unique authorship, and that to guarantee that dignity, they need the right to freedom, the right to equality, and the right to a decent life. However, in order to actually enter the door of protection of those rights, each individual must be stripped of their authorship, which is the core of their dignity.

_ Page 189

Furthermore, the author describes the long history of struggles by people with disabilities and minorities who invented new rights, such as the "right to mobility," to secure such uniqueness and authorship, the ability to write their own life stories.

Minorities who have strived to affirm their dignity through interactions with others and to incorporate it into law and institutions now face the question of beauty that remains: "Am I attractive in and of myself, without relying on law, morality, education, or human rights awareness?"

Through the concept of 'portrait drawing,' the author argues that if there is a gaze that can observe the life story of a person who has written it with his or her body and mind intact for a long time, if such a stage is given to everyone, even 'disqualified' beings can be beautiful and attractive.

Peter Dinklage, the actor who plays Tyrion in the American drama Game of Thrones, has achondroplasia.

(Omitted) Over the course of seven years, viewers follow Tyrion's entire life, integrating the character's appearance into the long-term experience created by his performance, rather than a single snapshot.

He is now being imprinted as the most attractive character in the entire play.

Of course, such acting itself is the result of the 'narrative' that the actor Peter Dinklage has built in his own life.

Tyrion's charm is never separated from that of the actor Peter Dinklage.

(syncopation)

All of these practices are about creating time and space for people who have limited self-expression to entrust their portraits to the human 'painters'.

A portrait painted like this will synthesize a person's life story, beliefs, inclinations, body mass and volume, proportions and curves, colors and scents, and voice.

If there is equal opportunity to be beautiful, then at least your bodies and mine can be somewhat beautiful.

_ Pages 276-285

Embracing your identity:

For those who cannot fully accept themselves

During a civil law class in my first year of law school, the author, the only student in a wheelchair, heard about the "wrongful life lawsuit."

He remembered that his illness could also be diagnosed in advance through genetic testing, and imagined his parents suing the doctor for damages, claiming that his birth was a loss.

The question I had been holding onto throughout my growing years—“Am I ugly, worthless, and inferior?”—felt like it was converging into the concept of “a wrong life.”

Since then, he has lived a life of struggle, trying to convince himself whether his life was a loss or a mistake, and if not, what the basis was, and what kind of awareness and attitude are necessary for a being with differences and deficiencies like his to accept them as his identity.

This book is a compilation of legal, social, philosophical, and empirical evidence gathered in the process.

In 2001, a deaf lesbian couple in the United States had a deaf son, Gobain, through sperm donation from a man who was born deaf for five generations.

The choice of those who deliberately pass on a disability to their children has sparked enormous ethical debate.

The author asks:

Is osteogenesis imperfecta a loss for me, and hearing impairment for Govin? A child born without osteogenesis imperfecta wouldn't be Kim Won-young, and Govin wouldn't exist if his parents hadn't deliberately chosen hearing impairment. So is being born into this world a loss rather than not being born? He argues that conditions that are completely attached to our bodies and become part of our existence—whether it's a disability, an ugly appearance, or a different gender identity—can never be a loss or a wrong, and if so, we have no choice but to accept them as a part of our identity.

What does it mean for a person to fully embrace their identity, defying the social stigma of being "wrong" or "disqualified"? The author experienced a sense of "sharing identity" while honing various wheelchair skills at a special education school and interacting with seniors who cared about the color and design of their wheelchairs.

I was able to share a "horizontal identity" that I could never share with my parents' generation, who tried to cure my disability or make me as close to "normal" as possible, and I was able to recognize myself as an individual, not as abnormal or deficient.

Gobang's parents, as hearing-impaired people, accepted their culture and lifestyle, which they had developed through sign language, as a complete identity and tried to share it with their child.

It was not about passing on a disability, but rather about conveying an identity and a world.

In other words, embracing one's identity means making the shared experiences and stories of those who have lived with such attributes and faced life's challenges a significant part of my self, and making an ethical decision to align my entire life plan with them.

“Children with disabilities like Sam and Julianna are not born destined to be gifts to their parents.

And yet, the reason those children are a gift to us is because we chose them.” (Omitted)

Let's say Ruth can't stand it anymore and believes, without any basis, that the child is a gift from God.

But one day, I found out that my child's disability was treatable, and in fact, the disability disappeared with medication.

(Omitted) Now Ruth may give up on showing interest in children with disabilities like her own or on thinking that such disabilities might be a gift.

Because there is no longer a need for 'strategic' faith to take charge of one's own destiny.

But if Ruth had accepted the disability itself, her practical choices would not have changed even after her child had been treated for the disability.

For Ruth, embracing her disability wasn't simply a strategic belief, but a practical choice that shifted a fundamental assumption of her life: that the lives of all children with disabilities matter, deserve respect, and are in some ways a gift.

_ Pages 140-143

To those who stand in the midst of resistance and struggle

Have we been taking sufficient care and protection of ourselves?

This book is steeped in the author's thoughts and experiences as he read, wrote, and fought to fully embrace his identity as a disabled person, unable to walk.

Has the author, who has struggled for so long to accept himself, now found comfort, no longer shaken? He asks another difficult question.

You've become a fierce fighter who embraces your identity and asserts your rights. Have you also succeeded in loving yourself? Have you cared for and cherished yourself sufficiently? He hopes that even if minorities, who must become strong and resilient to be recognized and avoid humiliation, ultimately fail in all these endeavors, they will never give up on loving and caring for themselves.

His final argument is not directed at those who have disqualified us.

His final words contain a sincere hope that we can embrace and love ourselves, even if we cannot fully accept some parts of ourselves.

You don't have to be a monster.

Even if your child or sibling has a disability and you have difficulty accepting them, they will still love you as their mother, father, older sister, or younger brother.

Even if you don't live a life of acceptance and courage in the face of adversity, your parents, siblings, lovers, friends, and neighbors will still have good reasons to love you.

We must strive to demonstrate that each other's lives can be respected and beautiful.

But in the midst of such struggles, at some point, you may find yourself lonely and unable to love yourself unless you take on the appearance of a strong fighter.

You don't have to do that.

How many people, living with disabilities, ugly faces, poverty, and discrimination based on race, gender, or sexual orientation, can confidently deny them all, practically embrace their "deficiencies," and stand as human beings who invent their rights before the law? Standing that way isn't the only way to be dignified and attractive.

This 'vulnerability', which we strive to accept and care for ourselves but can never fully achieve, is perhaps the common denominator that binds us together, despite our individual circumstances and belonging to different identity groups.

_ Page 310

Performance that constitutes class VS Performance that constitutes dignity

Everyone acts to some degree in their relationships with others.

Like an actor on stage, he performs the role required of him, controlling and coordinating himself.

This ability is called reflexivity.

Highly developed reflexivity leads to skill in relationships.

“Oh my, poor thing.

When asked, “How did you end up like that?” he wittily replied, “To get a discount for the disabled!” Or when parents got down on their knees to ask for consent to establish a special school for their disabled children, he would shout, “Stop putting on a show!” And then get down on his knees as well.

This sophistication protects the ego, but it also creates problems by preventing us from fully engaging with others or the situations we find ourselves in.

Surprisingly, the author finds the basis of human dignity in this theatrical aspect of life.

If we seek the reasons for the dignity of all human beings in concrete everyday life, without relying on human rights norms or laws, then these everyday performances will be the places of discovery.

However, this applies to 'performances that constitute dignity' rather than 'performances that constitute class' such as ceremonies for the powerful or political events that mobilize the disabled.

In a performance that constitutes dignity, all actors participating in it share reality (truth).

On top of that shared reality, they participate in the performance equally, actively responding to each other's acting.

A friend who quickly and naturally changes the topic of childcare when it comes to a college classmate who wants to have children but doesn't; a family who has dinner with a terminally ill loved one and converses as usual; a college student who nonchalantly turns his gaze to a book as if he's indifferent to a child with autism making a lot of noise at the cafe next to him.

They all share the same intention behind each other's acting.

(syncopation)

Interactions that respect each other as individuals reinforce that respect by sharing reality.

The anonymous college student who pretends not to know respects him out of gratitude, and the college student who knows the efforts of the parents of an autistic child who tries to respect him turns his attention to the book, pretending to be indifferent even more.

When we acknowledge that others are beings who react to our reactions, we begin to respect others, and through others who respect us, we begin to respect ourselves.

_ Pages 66-67

“We deny love and justice.”

_ The power to reap all the drama and declare oneself powerless

The author confesses that he tried to become more seasoned so as not to be mobilized for 'performances for class'.

Do my legs look even a little longer? Do I look like a poor, depressed, disabled person? He had difficulty escaping even a moment of reflection, and one day he encountered sentences that negated all this theatrical effort.

This was the code of conduct of the Blue Grass Society, an organization for people with cerebral palsy that emerged in Japan in the 1960s.

1.

We realize that we have cerebral palsy.

2.

We practice strong self-assertion.

3.

We deny love and justice.

4.

We don't choose the path to problem solving.

5.

We deny the civilization of the able-bodied.

_ Page 78

Faced with these sentences of pure negation, which deny the will to solve the problem, and even one's own potential and ability to put it into practice, the author reflects on himself, who had staged another play to counter the play of the qualityists.

In order to accept yourself as you are, shouldn't you at least once let go of everything and declare your helplessness?

The pressure to be witty, humorous, intelligent, and full of mental charm that compensates for physical shortcomings.

The mental burden of having to be polite and at least remember my colleagues' birthdays instead of being unable to change the office water bottle.

It's about letting go of all of this.

(syncopation)

The power to overcome paradoxical, other-oriented theater.

A power that is sometimes publicly declared to be powerless and insignificant.

The power to declare negation, that you can do nothing and have nothing.

There we see a form of authenticity that goes beyond other-orientedness.

(syncopation)

Completely denying the view of others and looking at myself only through my own eyes ultimately presupposes acceptance of my body, destiny, life, and existence.

_ Pages 91-92

“Then cut off your leg too.”

_ Josee of Josee, the Tiger and the Fish

If my child were born with a disability, would I be confident enough to actively welcome that child? The author poses the question: isn't it true that parents welcome even the "flaws" of their children—that we truly welcome the "flaws" of ourselves, our family, our loved ones, and our friends—the final gateway to affirming that all life can be dignified?

Until now, the way countries and societies have treated disabilities, illnesses, and other sexual identities has been to treat, correct, and train them to appear 'normal' as much as possible.

The author asks how long we must endure the effort to hide and change these traits, which are our very being, in order to become a 'sadly normal person', and suggests the attitude shown by Josee in the film Josee, the Tiger and the Fish.

Tsuneo's ex-lover, who had her boyfriend stolen by Jose, the disabled protagonist, comes to Jose and slaps him before saying:

“I wish I had no legs like you.”

Jose also responds with a blank expression after slapping the other person's cheek.

“Then cut off your leg too.” (omitted)

Grandmother advises Jose, who is suffering because of her relationship with Tsuneo, that "you shouldn't try to live like other people do."

Grandmother is Jose's sole guardian and the person who loves her the most, but in a 'vertical' relationship, that level of advice is the best that can be given.

Our loving grandmothers and mothers, our countries and communities that protect us, our religious leaders that seek to save us, and the teachings of the Bible never teach us, “Live according to your desires, and if others take issue with it, say, ‘Then cut off your leg too.’”

Only when we connect with other beings who have a horizontal identity can we build a style of mind that recognizes ourselves as a 'being' in itself, rather than as a lack of normality.

_ Pages 123-128

The law erases a person's life story.

According to the Mental Health and Welfare Act, anyone can be involuntarily admitted to a mental hospital if two family members apply for hospitalization and a doctor diagnoses the need.

Once you're 'legally' admitted, the only way to get out is to admit that you have a mental illness and voluntarily declare that you will undergo treatment.

The law doesn't listen to individual stories.

No matter how much I protest that I am not mentally ill, the gatekeepers of the law - social workers, judges, doctors, police - only follow the manual and do not listen to their life stories.

When a developmentally disabled person who wants to dress up and go out applies for activity support services, the examiner asks questions like, “Do you know how to boil ramen?”

A person's life, lived for decades, reacting to their physical and mental characteristics, is completely erased.

The author introduces "reason-forcing conversation," proposed by legal scholar Kenji Yoshino, as a way to somewhat improve the legal system that ignores the uniqueness of individuals.

Let's say that a disabled person who wants to receive activity support services is able to use his or her arms and legs to some extent from a medical standpoint and is capable of eating and using the toilet.

However, he applied for the activity support worker position because he “wanted to go out wearing a dark gray suit with a tie and product on my hair.”

His hands and feet are too weak to perform tasks like tying a tie.

The law, through the mouths of doctors and the National Pension Service, will ask:

"No, why do you insist on wearing a tie and suit? It's hard to provide support for someone like that."

But, in accordance with the principle of 'conversation that forces logical grounds', we must change the question.

“Why is it such a problem for the National Pension Service that I wear a tie and suit with the support of an activity support worker?” _ Page 201

Are the rights of people with disabilities to urinate and move a matter of welfare or freedom?

If a disabled student cannot study properly because there is no accessible restroom at school, or if the subway station does not have an elevator so he cannot get to his destination, what rights of his are being violated?

In the past, the country, society, and even people with disabilities themselves considered this a social welfare issue.

Because the state power did not physically restrain or threaten him to prevent him from going to the bathroom or riding the subway.

However, as democratization progressed and the "Disabled Persons Welfare Act" was enacted, disabled people began to feel that "movement" was not a matter of welfare or consideration, but rather something that confined them to their homes and tied their bodies to the stairs, that is, an infringement on their physical freedom.

Through this shift in perception, people with disabilities invented a new right called the "right to mobility," and fought fiercely to have it legally and socially recognized, including filing constitutional lawsuits and tying wheelchairs to subway tracks to stop trains.

In order for people with disabilities to invent their own right to move and have it incorporated into the legal system, they first had to get out on the streets and move on their own.

This shows that rights do not have real meaning only when they are recognized through the power of state power within the legal system.

The process of creating rights itself, the act of expressing the problems of one's body, mind, or social situation in the language of rights, sharing them collectively, and entering them into the legal system to give them real power, thereby giving them political, moral, and constitutional meaning, is a process by which the dignity of "wrong lives" is socially recognized.

_ Page 231

“I’m drawn to your severed body” _ Devotism

Even if laws, systems, morals, and ethics create a society free from discrimination, inconvenience, and insult, they cannot completely prevent those with limited attractive resources from being marginalized.

People with old, sick bodies, impaired legs, or distinctive appearances still struggle to enter society's informal networks, including deep friendships and sexual unions.

The author, who was not free from such worries, happened to learn about 'devotees', people who are sexually attracted to people with disabilities.

Many of them are attracted to the amputated bodies of disabled people.

Many people interpret this as sexual perversion or pathological fetishism, but isn't it better to desire the bodies of disabled people themselves without any preconceived notions or insulting gazes, rather than unilaterally bestowing 'sublimity' on them?

If you donate a large sum of money to the Salvation Army, but cannot even sit down for five minutes to eat with that body, cannot wait for that brief moment for that body to board the bus, and are opposed to building a school that many of those bodies attend, then that in itself is hateful and requires no further explanation.

Even if one feels religious sensitivity due to the fascination with the grandiose and romantic 'epic' fate that accompanies muscular dystrophy and osteogenesis imperfecta, this has nothing to do with love for that being.

You must desire the body.

No matter what religion, morality, or politics say, the declaration that you want to be with your 'body' is a desire for another person, and that is love.

_ Page 267

However, devotionalism has obvious limitations.

Because the desire for the body does not lead to the desire or love for the individual who lives with that body.

Devoted people reduce the real difficulties faced by people with disabilities to a matter of sexual desire, and fail to imagine issues such as discrimination, poverty, and mobility.

They are simply intoxicated with themselves for loving such a deficient other, believing that if only the disabled could become more aware of 'devotionalism', all their problems would be solved.

When the cave I was digging alone in despair met another cave

The author cites the example of Kenzaburo Oe in Japan in the 1960s, who raised a disabled child alone without any social network, and his own parents in the 1980s, and says that such personal experiences are now gradually coming together thanks to long-standing minority movements and internet-based networks.

If minorities change direction even just by one degree, we have entered an era where they can meet other caves and form a single world.

We all have moments of despair when we feel like we're digging a vertical tunnel, alone and disconnected from any meaningful network, with no apparent helping hand.

But in a hole that was thought to only go down vertically, some people succeed in changing direction a little.

As he turns his angle away from the vertical, their respective caves cease to be parallel, and it becomes possible for two or more people to meet at a certain point.

Only when people meet, talk, and join forces (even if underground) can a community be built.

(syncopation)

The cave, which had been dug only vertically, now joins forces and heads horizontally.

Soon we come across another cave that descends vertically.

The grid-like caves now form their own structure and form a world.

In an instant, sunlight began to pour in through the lattice holes in various places.

_ Pages 300-301

From personal experience to interaction with others, to law and institutions,

A long argument expanding into a social arena where anyone can be beautiful.

Won-Young Kim, a first-class disabled person, wrote a book in 2010 declaring that he refused to be a “disabled person who overcame disability,” a symbol of indomitable will and hope, and instead would become a “vulgar” disabled person, a “bad” disabled person.

Based on his personal story of how he, who had been confined to his room until the age of fifteen, went on to attend a school for the disabled and then Seoul National University Law School, he testified to the power of freedom and solidarity of courageous people who enabled minorities like himself to emerge into the world.

He was a young man of twenty-nine at the time, and in the book's epilogue, he said, "I hope to live a life where I can someday defend myself rather than testify, a life where I can tell my story with a little more confidence. That's the kind of life I want to live in my thirties."

Now in his thirties, he is a researcher and lawyer who has decided to go beyond expressing his anger and desires and instead advocate for the lives of those labeled as "wrong" or "disqualified" in our society.

To prevent them from living in pain, either by denying their very birth or by never being able to accept their physical and mental characteristics, I compiled evidence proving that all beings can be dignified and attractive, and wrote a lengthy defense.

How is human dignity discovered and built?

The author begins his discussion by examining the dilemma faced by minorities in the dramatic moments they encounter in their lives: how to deftly confront and gracefully confront discrimination, exclusion, shame, and humiliation.

This attitude of mind, adopted to protect oneself, turns every moment of life into a kind of performance.

Unexpectedly, this bears some resemblance to the theatrical lives of those who have insulted him, those who plan the ceremonies and mobilize the disabled.

However, rather than telling us to throw away false theater, the author borrows from the discussions of sociologist Erving Goffman and anthropologist Kim Hyun-kyung to say that theatrical interactions between people can develop in a way that builds human dignity.

A stage production by one child who stays with his disabled friend while all the other children run to the valley on a hot summer day, saying, “I need to take care of my skin,” and another child who understands his performance and sends his friend off with appropriate words.

Through this 'performance that constitutes dignity,' the author suggests the possibility that an individual who has been enduring pain alone can rise up as a dignified human being through encounters with others.

When my friend says, “You need to take care of your skin,” I know he’s lying because I respect him, so I agree with him.

In my response, he knows that I respect him, and he respects me even more.

When he respects me, I respect myself too.

In the end, I send him off to the valley he really wanted to go to, and he leaves, giving me a comic book and saving my self-esteem.

We acted with a deep understanding that we were each a single entity with desires and pride, and this performance made our existence more dense.

(syncopation)

The moment when human dignity shines most clearly is when people understand each other's performances and treat each other with dignity through interaction.

If character is formed through the performance of treating others appropriately, dignity is formed through the interaction of welcoming others and returning that hospitality.

Rather than saying that we treat each other that way because we are inherently dignified beings, we can say that dignity is 'constituted' only when we treat each other that way.

_ Pages 69-71

Minorities who have confirmed that they are dignified human beings through interactions with parents, siblings, friends, and lovers now go out into the world.

The author, a former lawyer and disability discrimination investigator at the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, points out that, based on his experience as a gatekeeper of the law and encountering those who are discriminated against, laws and systems fail to recognize the unique narratives of each individual, the most fundamental prerequisite for human dignity, in the name of protection, treatment, and welfare.

Whatever their complex and unique life stories, backgrounds, and bodily experiences, the law requires that they self-identify as mentally ill if they want to receive (effective, non-coercive) services.

In order to receive the protection and support of the law, it is a request to completely reduce a person's personality to the 'attributes' or 'background' that are precisely the reason for the protection, that is, to reduce their existence to just the physical and developmental disabilities themselves.

(syncopation)

The Constitution states that individuals have dignity because they possess unique authorship, and that to guarantee that dignity, they need the right to freedom, the right to equality, and the right to a decent life. However, in order to actually enter the door of protection of those rights, each individual must be stripped of their authorship, which is the core of their dignity.

_ Page 189

Furthermore, the author describes the long history of struggles by people with disabilities and minorities who invented new rights, such as the "right to mobility," to secure such uniqueness and authorship, the ability to write their own life stories.

Minorities who have strived to affirm their dignity through interactions with others and to incorporate it into law and institutions now face the question of beauty that remains: "Am I attractive in and of myself, without relying on law, morality, education, or human rights awareness?"

Through the concept of 'portrait drawing,' the author argues that if there is a gaze that can observe the life story of a person who has written it with his or her body and mind intact for a long time, if such a stage is given to everyone, even 'disqualified' beings can be beautiful and attractive.

Peter Dinklage, the actor who plays Tyrion in the American drama Game of Thrones, has achondroplasia.

(Omitted) Over the course of seven years, viewers follow Tyrion's entire life, integrating the character's appearance into the long-term experience created by his performance, rather than a single snapshot.

He is now being imprinted as the most attractive character in the entire play.

Of course, such acting itself is the result of the 'narrative' that the actor Peter Dinklage has built in his own life.

Tyrion's charm is never separated from that of the actor Peter Dinklage.

(syncopation)

All of these practices are about creating time and space for people who have limited self-expression to entrust their portraits to the human 'painters'.

A portrait painted like this will synthesize a person's life story, beliefs, inclinations, body mass and volume, proportions and curves, colors and scents, and voice.

If there is equal opportunity to be beautiful, then at least your bodies and mine can be somewhat beautiful.

_ Pages 276-285

Embracing your identity:

For those who cannot fully accept themselves

During a civil law class in my first year of law school, the author, the only student in a wheelchair, heard about the "wrongful life lawsuit."

He remembered that his illness could also be diagnosed in advance through genetic testing, and imagined his parents suing the doctor for damages, claiming that his birth was a loss.

The question I had been holding onto throughout my growing years—“Am I ugly, worthless, and inferior?”—felt like it was converging into the concept of “a wrong life.”

Since then, he has lived a life of struggle, trying to convince himself whether his life was a loss or a mistake, and if not, what the basis was, and what kind of awareness and attitude are necessary for a being with differences and deficiencies like his to accept them as his identity.

This book is a compilation of legal, social, philosophical, and empirical evidence gathered in the process.

In 2001, a deaf lesbian couple in the United States had a deaf son, Gobain, through sperm donation from a man who was born deaf for five generations.

The choice of those who deliberately pass on a disability to their children has sparked enormous ethical debate.

The author asks:

Is osteogenesis imperfecta a loss for me, and hearing impairment for Govin? A child born without osteogenesis imperfecta wouldn't be Kim Won-young, and Govin wouldn't exist if his parents hadn't deliberately chosen hearing impairment. So is being born into this world a loss rather than not being born? He argues that conditions that are completely attached to our bodies and become part of our existence—whether it's a disability, an ugly appearance, or a different gender identity—can never be a loss or a wrong, and if so, we have no choice but to accept them as a part of our identity.

What does it mean for a person to fully embrace their identity, defying the social stigma of being "wrong" or "disqualified"? The author experienced a sense of "sharing identity" while honing various wheelchair skills at a special education school and interacting with seniors who cared about the color and design of their wheelchairs.

I was able to share a "horizontal identity" that I could never share with my parents' generation, who tried to cure my disability or make me as close to "normal" as possible, and I was able to recognize myself as an individual, not as abnormal or deficient.

Gobang's parents, as hearing-impaired people, accepted their culture and lifestyle, which they had developed through sign language, as a complete identity and tried to share it with their child.

It was not about passing on a disability, but rather about conveying an identity and a world.

In other words, embracing one's identity means making the shared experiences and stories of those who have lived with such attributes and faced life's challenges a significant part of my self, and making an ethical decision to align my entire life plan with them.

“Children with disabilities like Sam and Julianna are not born destined to be gifts to their parents.

And yet, the reason those children are a gift to us is because we chose them.” (Omitted)

Let's say Ruth can't stand it anymore and believes, without any basis, that the child is a gift from God.

But one day, I found out that my child's disability was treatable, and in fact, the disability disappeared with medication.

(Omitted) Now Ruth may give up on showing interest in children with disabilities like her own or on thinking that such disabilities might be a gift.

Because there is no longer a need for 'strategic' faith to take charge of one's own destiny.

But if Ruth had accepted the disability itself, her practical choices would not have changed even after her child had been treated for the disability.

For Ruth, embracing her disability wasn't simply a strategic belief, but a practical choice that shifted a fundamental assumption of her life: that the lives of all children with disabilities matter, deserve respect, and are in some ways a gift.

_ Pages 140-143

To those who stand in the midst of resistance and struggle

Have we been taking sufficient care and protection of ourselves?

This book is steeped in the author's thoughts and experiences as he read, wrote, and fought to fully embrace his identity as a disabled person, unable to walk.

Has the author, who has struggled for so long to accept himself, now found comfort, no longer shaken? He asks another difficult question.

You've become a fierce fighter who embraces your identity and asserts your rights. Have you also succeeded in loving yourself? Have you cared for and cherished yourself sufficiently? He hopes that even if minorities, who must become strong and resilient to be recognized and avoid humiliation, ultimately fail in all these endeavors, they will never give up on loving and caring for themselves.

His final argument is not directed at those who have disqualified us.

His final words contain a sincere hope that we can embrace and love ourselves, even if we cannot fully accept some parts of ourselves.

You don't have to be a monster.

Even if your child or sibling has a disability and you have difficulty accepting them, they will still love you as their mother, father, older sister, or younger brother.

Even if you don't live a life of acceptance and courage in the face of adversity, your parents, siblings, lovers, friends, and neighbors will still have good reasons to love you.

We must strive to demonstrate that each other's lives can be respected and beautiful.

But in the midst of such struggles, at some point, you may find yourself lonely and unable to love yourself unless you take on the appearance of a strong fighter.

You don't have to do that.

How many people, living with disabilities, ugly faces, poverty, and discrimination based on race, gender, or sexual orientation, can confidently deny them all, practically embrace their "deficiencies," and stand as human beings who invent their rights before the law? Standing that way isn't the only way to be dignified and attractive.

This 'vulnerability', which we strive to accept and care for ourselves but can never fully achieve, is perhaps the common denominator that binds us together, despite our individual circumstances and belonging to different identity groups.

_ Page 310

Performance that constitutes class VS Performance that constitutes dignity

Everyone acts to some degree in their relationships with others.

Like an actor on stage, he performs the role required of him, controlling and coordinating himself.

This ability is called reflexivity.

Highly developed reflexivity leads to skill in relationships.

“Oh my, poor thing.

When asked, “How did you end up like that?” he wittily replied, “To get a discount for the disabled!” Or when parents got down on their knees to ask for consent to establish a special school for their disabled children, he would shout, “Stop putting on a show!” And then get down on his knees as well.

This sophistication protects the ego, but it also creates problems by preventing us from fully engaging with others or the situations we find ourselves in.

Surprisingly, the author finds the basis of human dignity in this theatrical aspect of life.

If we seek the reasons for the dignity of all human beings in concrete everyday life, without relying on human rights norms or laws, then these everyday performances will be the places of discovery.

However, this applies to 'performances that constitute dignity' rather than 'performances that constitute class' such as ceremonies for the powerful or political events that mobilize the disabled.

In a performance that constitutes dignity, all actors participating in it share reality (truth).

On top of that shared reality, they participate in the performance equally, actively responding to each other's acting.

A friend who quickly and naturally changes the topic of childcare when it comes to a college classmate who wants to have children but doesn't; a family who has dinner with a terminally ill loved one and converses as usual; a college student who nonchalantly turns his gaze to a book as if he's indifferent to a child with autism making a lot of noise at the cafe next to him.

They all share the same intention behind each other's acting.

(syncopation)

Interactions that respect each other as individuals reinforce that respect by sharing reality.

The anonymous college student who pretends not to know respects him out of gratitude, and the college student who knows the efforts of the parents of an autistic child who tries to respect him turns his attention to the book, pretending to be indifferent even more.

When we acknowledge that others are beings who react to our reactions, we begin to respect others, and through others who respect us, we begin to respect ourselves.

_ Pages 66-67

“We deny love and justice.”

_ The power to reap all the drama and declare oneself powerless

The author confesses that he tried to become more seasoned so as not to be mobilized for 'performances for class'.

Do my legs look even a little longer? Do I look like a poor, depressed, disabled person? He had difficulty escaping even a moment of reflection, and one day he encountered sentences that negated all this theatrical effort.

This was the code of conduct of the Blue Grass Society, an organization for people with cerebral palsy that emerged in Japan in the 1960s.

1.

We realize that we have cerebral palsy.

2.

We practice strong self-assertion.

3.

We deny love and justice.

4.

We don't choose the path to problem solving.

5.

We deny the civilization of the able-bodied.

_ Page 78

Faced with these sentences of pure negation, which deny the will to solve the problem, and even one's own potential and ability to put it into practice, the author reflects on himself, who had staged another play to counter the play of the qualityists.

In order to accept yourself as you are, shouldn't you at least once let go of everything and declare your helplessness?

The pressure to be witty, humorous, intelligent, and full of mental charm that compensates for physical shortcomings.

The mental burden of having to be polite and at least remember my colleagues' birthdays instead of being unable to change the office water bottle.

It's about letting go of all of this.

(syncopation)

The power to overcome paradoxical, other-oriented theater.

A power that is sometimes publicly declared to be powerless and insignificant.

The power to declare negation, that you can do nothing and have nothing.

There we see a form of authenticity that goes beyond other-orientedness.

(syncopation)

Completely denying the view of others and looking at myself only through my own eyes ultimately presupposes acceptance of my body, destiny, life, and existence.

_ Pages 91-92

“Then cut off your leg too.”

_ Josee of Josee, the Tiger and the Fish

If my child were born with a disability, would I be confident enough to actively welcome that child? The author poses the question: isn't it true that parents welcome even the "flaws" of their children—that we truly welcome the "flaws" of ourselves, our family, our loved ones, and our friends—the final gateway to affirming that all life can be dignified?

Until now, the way countries and societies have treated disabilities, illnesses, and other sexual identities has been to treat, correct, and train them to appear 'normal' as much as possible.

The author asks how long we must endure the effort to hide and change these traits, which are our very being, in order to become a 'sadly normal person', and suggests the attitude shown by Josee in the film Josee, the Tiger and the Fish.

Tsuneo's ex-lover, who had her boyfriend stolen by Jose, the disabled protagonist, comes to Jose and slaps him before saying:

“I wish I had no legs like you.”

Jose also responds with a blank expression after slapping the other person's cheek.

“Then cut off your leg too.” (omitted)

Grandmother advises Jose, who is suffering because of her relationship with Tsuneo, that "you shouldn't try to live like other people do."

Grandmother is Jose's sole guardian and the person who loves her the most, but in a 'vertical' relationship, that level of advice is the best that can be given.

Our loving grandmothers and mothers, our countries and communities that protect us, our religious leaders that seek to save us, and the teachings of the Bible never teach us, “Live according to your desires, and if others take issue with it, say, ‘Then cut off your leg too.’”

Only when we connect with other beings who have a horizontal identity can we build a style of mind that recognizes ourselves as a 'being' in itself, rather than as a lack of normality.

_ Pages 123-128

The law erases a person's life story.

According to the Mental Health and Welfare Act, anyone can be involuntarily admitted to a mental hospital if two family members apply for hospitalization and a doctor diagnoses the need.

Once you're 'legally' admitted, the only way to get out is to admit that you have a mental illness and voluntarily declare that you will undergo treatment.

The law doesn't listen to individual stories.

No matter how much I protest that I am not mentally ill, the gatekeepers of the law - social workers, judges, doctors, police - only follow the manual and do not listen to their life stories.

When a developmentally disabled person who wants to dress up and go out applies for activity support services, the examiner asks questions like, “Do you know how to boil ramen?”

A person's life, lived for decades, reacting to their physical and mental characteristics, is completely erased.

The author introduces "reason-forcing conversation," proposed by legal scholar Kenji Yoshino, as a way to somewhat improve the legal system that ignores the uniqueness of individuals.

Let's say that a disabled person who wants to receive activity support services is able to use his or her arms and legs to some extent from a medical standpoint and is capable of eating and using the toilet.

However, he applied for the activity support worker position because he “wanted to go out wearing a dark gray suit with a tie and product on my hair.”

His hands and feet are too weak to perform tasks like tying a tie.

The law, through the mouths of doctors and the National Pension Service, will ask:

"No, why do you insist on wearing a tie and suit? It's hard to provide support for someone like that."

But, in accordance with the principle of 'conversation that forces logical grounds', we must change the question.

“Why is it such a problem for the National Pension Service that I wear a tie and suit with the support of an activity support worker?” _ Page 201

Are the rights of people with disabilities to urinate and move a matter of welfare or freedom?

If a disabled student cannot study properly because there is no accessible restroom at school, or if the subway station does not have an elevator so he cannot get to his destination, what rights of his are being violated?

In the past, the country, society, and even people with disabilities themselves considered this a social welfare issue.

Because the state power did not physically restrain or threaten him to prevent him from going to the bathroom or riding the subway.

However, as democratization progressed and the "Disabled Persons Welfare Act" was enacted, disabled people began to feel that "movement" was not a matter of welfare or consideration, but rather something that confined them to their homes and tied their bodies to the stairs, that is, an infringement on their physical freedom.

Through this shift in perception, people with disabilities invented a new right called the "right to mobility," and fought fiercely to have it legally and socially recognized, including filing constitutional lawsuits and tying wheelchairs to subway tracks to stop trains.

In order for people with disabilities to invent their own right to move and have it incorporated into the legal system, they first had to get out on the streets and move on their own.

This shows that rights do not have real meaning only when they are recognized through the power of state power within the legal system.

The process of creating rights itself, the act of expressing the problems of one's body, mind, or social situation in the language of rights, sharing them collectively, and entering them into the legal system to give them real power, thereby giving them political, moral, and constitutional meaning, is a process by which the dignity of "wrong lives" is socially recognized.

_ Page 231

“I’m drawn to your severed body” _ Devotism

Even if laws, systems, morals, and ethics create a society free from discrimination, inconvenience, and insult, they cannot completely prevent those with limited attractive resources from being marginalized.

People with old, sick bodies, impaired legs, or distinctive appearances still struggle to enter society's informal networks, including deep friendships and sexual unions.

The author, who was not free from such worries, happened to learn about 'devotees', people who are sexually attracted to people with disabilities.

Many of them are attracted to the amputated bodies of disabled people.

Many people interpret this as sexual perversion or pathological fetishism, but isn't it better to desire the bodies of disabled people themselves without any preconceived notions or insulting gazes, rather than unilaterally bestowing 'sublimity' on them?

If you donate a large sum of money to the Salvation Army, but cannot even sit down for five minutes to eat with that body, cannot wait for that brief moment for that body to board the bus, and are opposed to building a school that many of those bodies attend, then that in itself is hateful and requires no further explanation.

Even if one feels religious sensitivity due to the fascination with the grandiose and romantic 'epic' fate that accompanies muscular dystrophy and osteogenesis imperfecta, this has nothing to do with love for that being.

You must desire the body.

No matter what religion, morality, or politics say, the declaration that you want to be with your 'body' is a desire for another person, and that is love.

_ Page 267

However, devotionalism has obvious limitations.

Because the desire for the body does not lead to the desire or love for the individual who lives with that body.

Devoted people reduce the real difficulties faced by people with disabilities to a matter of sexual desire, and fail to imagine issues such as discrimination, poverty, and mobility.

They are simply intoxicated with themselves for loving such a deficient other, believing that if only the disabled could become more aware of 'devotionalism', all their problems would be solved.

When the cave I was digging alone in despair met another cave

The author cites the example of Kenzaburo Oe in Japan in the 1960s, who raised a disabled child alone without any social network, and his own parents in the 1980s, and says that such personal experiences are now gradually coming together thanks to long-standing minority movements and internet-based networks.

If minorities change direction even just by one degree, we have entered an era where they can meet other caves and form a single world.

We all have moments of despair when we feel like we're digging a vertical tunnel, alone and disconnected from any meaningful network, with no apparent helping hand.

But in a hole that was thought to only go down vertically, some people succeed in changing direction a little.

As he turns his angle away from the vertical, their respective caves cease to be parallel, and it becomes possible for two or more people to meet at a certain point.

Only when people meet, talk, and join forces (even if underground) can a community be built.

(syncopation)

The cave, which had been dug only vertically, now joins forces and heads horizontally.

Soon we come across another cave that descends vertically.

The grid-like caves now form their own structure and form a world.

In an instant, sunlight began to pour in through the lattice holes in various places.

_ Pages 300-301

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 15, 2018

- Page count, weight, size: 324 pages | 488g | 140*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791160943733

- ISBN10: 1160943737

- KC Certification: Certification Type: Confirming Certification Number: -

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)