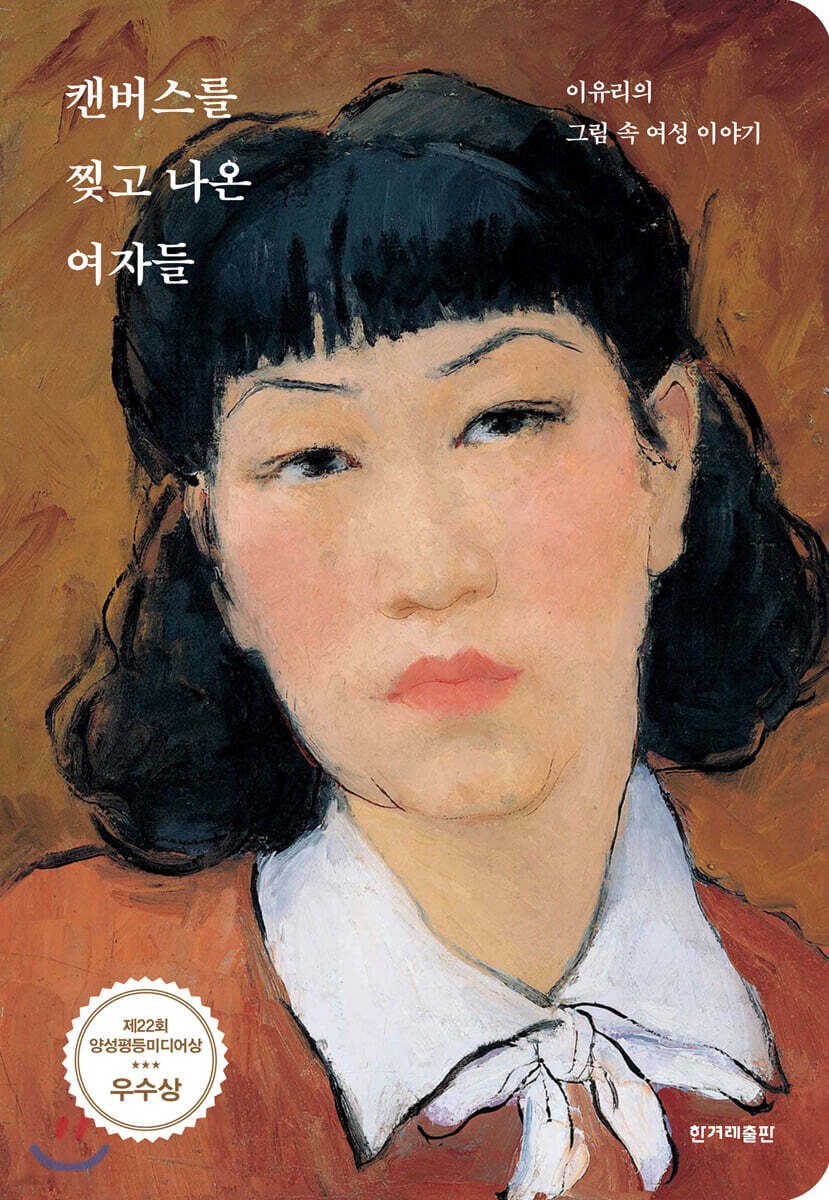

Women who tore through the canvas

|

Description

Book Introduction

The 22nd Gender Equality Media Awards Excellence Award Winner Picasso, Gauguin, Rembrandt, Giacometti… After they produced their masterpiece, there were 'women' 'Women' hidden behind men's canvases Walk out of the picture A new work by author Lee Yu-ri, author of 『The Painter's Last Painting』, 『Artworks that Changed the World』, and 『The Painter's Rising Works』, has been published. The author, who has been loved by readers for telling 'hidden' stories about painters and paintings in her previous works, has revealed the stories of women who were 'hidden' by men's canvases in this book, 'Women Who Torn the Canvas'. It contains the stories of women who played a major role behind the scenes in creating masterpieces by artists of the century such as Picasso, Gauguin, Rembrandt, and Giacometti, as well as stories of female artists who had outstanding talent but were not properly recognized, such as Pan Weiliang, Mary Cassatt, and Berthe Morisot. Before being wives, muses, and artists, these women have always suffered as the 'foundation' that supports patriarchal society. Through this book, the author also seeks to expose the violence against women that male-dominated society has turned a blind eye to. "Women Who Torn the Canvas" is an indictment of an era that disguised women's suffering as art, and a process of revealing that the artist's interpretation of the women in the painting was not "strange" or "fresh," but "correct." “Through this book, readers will be able to reflect on how women have been represented in paintings and what kind of violence men have inflicted on women. “Furthermore, I would be most grateful if this book provides an opportunity for reflection on whether this issue is closely connected to 21st century Korean society.” - From the author’s words |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Author's Note

Part 1: Women, Made

- “We do not wear clothes, our clothes wear us.”

- The lie that a woman's enemy is another woman

- Sometimes cute, sometimes like a mother?

Picasso, a great artist or a grooming perpetrator?

- Rembrandt and 'The Secret Lover'

- Girls want blue too

- Women also have the right to draw 'this kind of' work.

- Why is the history of old age and ugliness the lot of women?

Part 2 Women: We Are Not Possessions

- Even without Manet, Morisot is Morisot.

- A woman who refused to 'make a wife'

- Is this the martyrdom of women or the suffering of women?

- Hoping that the patriarchy will one day be broken

- Rubens' 'true' intentions behind painting 'Cimon and Pero'

- Gauguin and his descendants' fantasy of 'foreign women'

- Giacometti's 'sculptures' that blossomed amidst his wife's devotion

- A woman's appearance that is neither too pretty nor too ugly

Part 3: Women Have the Right to Safety

- The witch hunt is still not over

- Are men originally beasts?

- Look at the 'survival'!

- “Being born a woman is a terrible tragedy.”

- Who throws stones at 'drinking women'?

- A woman's body is a battlefield without gunfire.

Part 4 Women: We Are Ourselves

- “I will paint my picture with confidence.”

- Ladies, wear glasses and blue stockings.

- For my daughter's independence

- I like a woman who speaks and thinks clearly.

- Women have always existed throughout history.

- Why women had no choice but to borrow men's names

- When we need to return their names and voices

- I just drew a picture that was 'my own'

References

Part 1: Women, Made

- “We do not wear clothes, our clothes wear us.”

- The lie that a woman's enemy is another woman

- Sometimes cute, sometimes like a mother?

Picasso, a great artist or a grooming perpetrator?

- Rembrandt and 'The Secret Lover'

- Girls want blue too

- Women also have the right to draw 'this kind of' work.

- Why is the history of old age and ugliness the lot of women?

Part 2 Women: We Are Not Possessions

- Even without Manet, Morisot is Morisot.

- A woman who refused to 'make a wife'

- Is this the martyrdom of women or the suffering of women?

- Hoping that the patriarchy will one day be broken

- Rubens' 'true' intentions behind painting 'Cimon and Pero'

- Gauguin and his descendants' fantasy of 'foreign women'

- Giacometti's 'sculptures' that blossomed amidst his wife's devotion

- A woman's appearance that is neither too pretty nor too ugly

Part 3: Women Have the Right to Safety

- The witch hunt is still not over

- Are men originally beasts?

- Look at the 'survival'!

- “Being born a woman is a terrible tragedy.”

- Who throws stones at 'drinking women'?

- A woman's body is a battlefield without gunfire.

Part 4 Women: We Are Ourselves

- “I will paint my picture with confidence.”

- Ladies, wear glasses and blue stockings.

- For my daughter's independence

- I like a woman who speaks and thinks clearly.

- Women have always existed throughout history.

- Why women had no choice but to borrow men's names

- When we need to return their names and voices

- I just drew a picture that was 'my own'

References

Detailed image

Into the book

There is a term called 'grooming sexual violence'.

This term refers to an act in which the perpetrator gains favor with the victim or creates an intimate relationship with them, psychologically dominates them, and then satisfies sexual desire.

As a result, some victims believe that the abuser's actions are love.

Marie-Thérèse did.

"Even if the world doesn't understand, this is true love." This is a common excuse for sex offenders.

Picasso did the same.

Even Picasso's great art cannot hide the fact that he was a grooming sexual assault perpetrator.

Isn't that right?

--- p.53

Women who lived under the patriarchal system and died in vain, hearing the saying, “When a hen crows, the household falls apart.”

Women who had no say and had no choice but to choose death.

Aren't they the Korean version of the nagging women, Heirtier and Catherine?

Only after death could the virgin ghost visit the magistrate's room and speak to him.

I think that is why we feel both fear and deep sadness when we see the appearance of the virgin ghosts in legends and tales.

--- p.62

In reality, most "real girls" are neither so passive, nor so expressionless, nor do they alternate between innocence and provocation.

A campaign video for a famous American household goods brand once garnered much attention.

When we put adults in front of the camera and told them to “run like a little girl,” they ran with their arms waving comically.

So what would have happened if the same order had been given to real girls? Contrary to popular belief, they ran around with vigor and energy, "like girls."

I ordered it once for the girl in my house.

“Imagine being a child model and posing for me,” I said. The child then grabbed his waist with both hands and smiled, his face contorted into a wry grin.

It was the moment when I met the appearance of a 'real girl' in reality.

--- p.86~88

Australian comedian and disabled person with a rare genetic condition called osteogenesis imperfecta, Stella Young, said:

“I am not a person who exists to impress you.” He criticized the phenomenon of disabled people’s struggles being consumed as a human story to motivate non-disabled people, calling it “emotion porn.”

This advice also applies to the artist's paintings.

“My poverty, the misery of my life, the pain etched on my body are not tools to inspire an artist.”

It is objectification of the victim, voyeurism disguised as a cause, and nothing more than 'pain porn.'

--- p.117

The world is cruel and merciless to wives who spend their husbands' money.

On the other hand, she is too generous to husbands who steal her wife's time.

Patriarchal societies also encourage wives to be more devoted, as the more a husband exploits his wife's life and time, the more successful he becomes.

A woman's life in a patriarchal system is like a game of 'snakes and ladders'.

Even if you work hard to climb the ladder of life, the moment you become a wife, there is a high probability that you will slide down the snake.

This is precisely why we can never point fingers at single women and call them 'selfish'.

Who would play a game they are sure to lose?

--- p.154

I found myself scratching my forehead several times while reading material about the lives and art world of female artists.

This is because there were many records where, after talking about their talents for a long time, a review of their appearance was suddenly inserted.

For example, art historian Gail Levin said the following about American abstract expressionist painter Lee Krasner (1908–1984):

“I never thought Krasner was ugly, but after her death, some acquaintances and writers emphasized that Krasner was not beautiful.

Krasner's schoolmates said she was terribly ugly but had elegant style.” When referring to Krasner's husband, Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), the master of "action painting," they don't say, "He was bald, but he had a wild charm."

Because the appearance of a male artist is not that important.

--- p.156

It is not hard to understand why talented women would go out of their way to 'act like men'.

Even the French writer George Sand is like that.

(…) What if Sand had debuted under her real name, Aurore Dupin, rather than the male pen name, Georges? In a literary world so deeply prejudiced against women, it would have been difficult for Sand to succeed as a novelist from the start.

There has never been a time in history when there were no women.

(…) Just as words in male language are being replaced with gender-neutral words, shouldn’t we now also restore their original faces?

This term refers to an act in which the perpetrator gains favor with the victim or creates an intimate relationship with them, psychologically dominates them, and then satisfies sexual desire.

As a result, some victims believe that the abuser's actions are love.

Marie-Thérèse did.

"Even if the world doesn't understand, this is true love." This is a common excuse for sex offenders.

Picasso did the same.

Even Picasso's great art cannot hide the fact that he was a grooming sexual assault perpetrator.

Isn't that right?

--- p.53

Women who lived under the patriarchal system and died in vain, hearing the saying, “When a hen crows, the household falls apart.”

Women who had no say and had no choice but to choose death.

Aren't they the Korean version of the nagging women, Heirtier and Catherine?

Only after death could the virgin ghost visit the magistrate's room and speak to him.

I think that is why we feel both fear and deep sadness when we see the appearance of the virgin ghosts in legends and tales.

--- p.62

In reality, most "real girls" are neither so passive, nor so expressionless, nor do they alternate between innocence and provocation.

A campaign video for a famous American household goods brand once garnered much attention.

When we put adults in front of the camera and told them to “run like a little girl,” they ran with their arms waving comically.

So what would have happened if the same order had been given to real girls? Contrary to popular belief, they ran around with vigor and energy, "like girls."

I ordered it once for the girl in my house.

“Imagine being a child model and posing for me,” I said. The child then grabbed his waist with both hands and smiled, his face contorted into a wry grin.

It was the moment when I met the appearance of a 'real girl' in reality.

--- p.86~88

Australian comedian and disabled person with a rare genetic condition called osteogenesis imperfecta, Stella Young, said:

“I am not a person who exists to impress you.” He criticized the phenomenon of disabled people’s struggles being consumed as a human story to motivate non-disabled people, calling it “emotion porn.”

This advice also applies to the artist's paintings.

“My poverty, the misery of my life, the pain etched on my body are not tools to inspire an artist.”

It is objectification of the victim, voyeurism disguised as a cause, and nothing more than 'pain porn.'

--- p.117

The world is cruel and merciless to wives who spend their husbands' money.

On the other hand, she is too generous to husbands who steal her wife's time.

Patriarchal societies also encourage wives to be more devoted, as the more a husband exploits his wife's life and time, the more successful he becomes.

A woman's life in a patriarchal system is like a game of 'snakes and ladders'.

Even if you work hard to climb the ladder of life, the moment you become a wife, there is a high probability that you will slide down the snake.

This is precisely why we can never point fingers at single women and call them 'selfish'.

Who would play a game they are sure to lose?

--- p.154

I found myself scratching my forehead several times while reading material about the lives and art world of female artists.

This is because there were many records where, after talking about their talents for a long time, a review of their appearance was suddenly inserted.

For example, art historian Gail Levin said the following about American abstract expressionist painter Lee Krasner (1908–1984):

“I never thought Krasner was ugly, but after her death, some acquaintances and writers emphasized that Krasner was not beautiful.

Krasner's schoolmates said she was terribly ugly but had elegant style.” When referring to Krasner's husband, Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), the master of "action painting," they don't say, "He was bald, but he had a wild charm."

Because the appearance of a male artist is not that important.

--- p.156

It is not hard to understand why talented women would go out of their way to 'act like men'.

Even the French writer George Sand is like that.

(…) What if Sand had debuted under her real name, Aurore Dupin, rather than the male pen name, Georges? In a literary world so deeply prejudiced against women, it would have been difficult for Sand to succeed as a novelist from the start.

There has never been a time in history when there were no women.

(…) Just as words in male language are being replaced with gender-neutral words, shouldn’t we now also restore their original faces?

--- p.258, 260, 265

Publisher's Review

Martyrdom or Suffering for Women

The 'truths' in the painting that need to be revisited crookedly

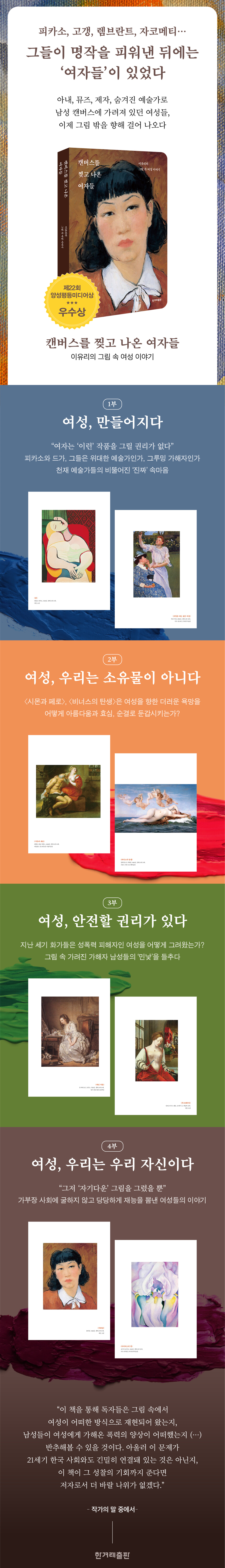

The book is divided into four parts.

Part 1, “Women, Made,” contains stories of women who were made, rather than born, into a patriarchal society.

It is a male-centered patriarchal society that criticizes women for not being able to draw 'this kind of' work, spreads malicious rumors that women's enemies are other women, and orders women to be sometimes cute and sometimes motherly.

Edgar Degas, one of the founders of Impressionism, criticized Mary Cassatt's painting "Young Woman Picking Fruit," saying that it was not a painting that a woman could paint.

Degas's criticism was what we would call 'gaslighting' against women these days.

What about Picasso, who is considered a great artist?

He seduced and psychologically dominated the young and beautiful Marie Baltez (page 49) with all kinds of sweet words in order to make her his muse.

Even putting aside his genius, there is no denying that he is a 'grooming' sex offender.

The desire to use women as tools, to manipulate them, to make them into women is no exception in art.

Part 2, “Women, We Are Not Possessions,” contains a critical look at the patriarchal society that regards women as possessions and objectifies them.

In a society that constantly whispers to women that they are inferior, women suffer from 'impostor syndrome', a psychological condition in which they are unable to recognize their own abilities, consider them coincidences, and feel anxious.

Berthe Morisot, an 18th-century French painter who displayed exceptional talent, suffered from imposter syndrome due to the neglect and interference of Edouard Manet, and the same is true for modern women in the 21st century.

Natalie Portman and Michelle Obama have also suffered from imposter syndrome.

The misconception that women are the property of men is also connected to the idea that women are only seen as sexual objects for men.

Therefore, we should no longer see beauty, filial piety, and purity in the women in Francesco Guarino's "The Martyrdom of Saint Agatha" (p. 113), Alexandre Cabanel's "The Birth of Venus" (p. 120), and Peter Paul Rubens's "Cimon and Pero" (p. 128).

The book says that the fact that we can see the dirty desires towards women is proof that our society has changed.

He further rebukes them, saying that our society can only mature if we accept different interpretations of these women.

Women are not inferior beings, food, tools, or objects of voyeurism.

Part 3, “Women Have the Right to Safety,” examines the sexual oppression and violence experienced by women in paintings from the 16th to 18th centuries and asks how much has changed in this era.

It has been a long time since women's behavior was controlled with the absurd claim that 'men are beasts'.

In the early 16th century painting by Ambrosius Benson, Lucretia (p. 185), a woman attempts to take her own life after being sexually assaulted.

In 1736, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, in his painting The Broken Mirror (p. 177), portrayed a woman who had lost her chastity, portraying her as impulsive and driven to madness.

Both paintings attribute the cause of the incident to the female victim rather than the male perpetrator.

Artemisia Gentileschi is a painter who actively exposed her sexual assault and accused the perpetrator during these dark times.

In her “Self-Portrait” (page 189), in which she proclaims to the world that she is an artist, not a victim of sexual violence who must be “pitiful” as society wants, we can see her proud “survivor-likeness” rather than her “victim-likeness.”

(Page 188) In order to protect women's right to safety and to create such a society, we must say this.

“The price for committing a crime falls on the perpetrator.

“The perpetrator goes to prison, the victim goes back to everyday life.” (p. 190)

Part 4, “Women, We Are Ourselves,” is the story of women who proudly displayed their talents without being swayed by the times.

Pan Yuliang, the first female oil painter in China and the first Chinese to win an award at an Italian art exhibition; Anna Dorothea Terbusch, who wore glasses and read books to show off her intellectual side, in short, painted self-portraits claiming to be a figure that men disliked; and Mary Moser and Georgia O'Keeffe, who proudly showed off their skills by painting pictures that were true to themselves.

Here we have gathered the stories of female artists who threw off the shackles imposed on women and lived their own lives.

On the other hand, it also captures the stories of women who wanted to live as themselves, such as Jane Eyre, George Sand, and Queen Christina, who could only display their talents by borrowing a man's name.

Now it's time to give them back their real names.

Mary Moser and Georgia O'Keeffe,

They didn't paint 'feminine' pictures.

I just drew a picture that was 'my own'

When we rebel against the stereotypes of women as interpreted by patriarchal society, we can see the true face of women.

Women Who Torn the Canvas offers a perverse sense of the women found in paintings from the past century.

Because you have to be able to see things crookedly to discover the true sense.

Only then can we say that it is not the martyrdom of women, but the suffering of women, and not the devotion of women, but the despair and sorrow of women.

The author wrote this book in the hope that the patriarchal society, which cleverly tries to protect the sexual play of women with beauty and purity, will one day be shattered (p. 125).

Now women have taken the 'red pill' (p. 125) from the matrix of patriarchal society.

It is irreversible.

So, watch the women walk out of the painting with strength and clap your hands until your palms hurt.

The 'truths' in the painting that need to be revisited crookedly

The book is divided into four parts.

Part 1, “Women, Made,” contains stories of women who were made, rather than born, into a patriarchal society.

It is a male-centered patriarchal society that criticizes women for not being able to draw 'this kind of' work, spreads malicious rumors that women's enemies are other women, and orders women to be sometimes cute and sometimes motherly.

Edgar Degas, one of the founders of Impressionism, criticized Mary Cassatt's painting "Young Woman Picking Fruit," saying that it was not a painting that a woman could paint.

Degas's criticism was what we would call 'gaslighting' against women these days.

What about Picasso, who is considered a great artist?

He seduced and psychologically dominated the young and beautiful Marie Baltez (page 49) with all kinds of sweet words in order to make her his muse.

Even putting aside his genius, there is no denying that he is a 'grooming' sex offender.

The desire to use women as tools, to manipulate them, to make them into women is no exception in art.

Part 2, “Women, We Are Not Possessions,” contains a critical look at the patriarchal society that regards women as possessions and objectifies them.

In a society that constantly whispers to women that they are inferior, women suffer from 'impostor syndrome', a psychological condition in which they are unable to recognize their own abilities, consider them coincidences, and feel anxious.

Berthe Morisot, an 18th-century French painter who displayed exceptional talent, suffered from imposter syndrome due to the neglect and interference of Edouard Manet, and the same is true for modern women in the 21st century.

Natalie Portman and Michelle Obama have also suffered from imposter syndrome.

The misconception that women are the property of men is also connected to the idea that women are only seen as sexual objects for men.

Therefore, we should no longer see beauty, filial piety, and purity in the women in Francesco Guarino's "The Martyrdom of Saint Agatha" (p. 113), Alexandre Cabanel's "The Birth of Venus" (p. 120), and Peter Paul Rubens's "Cimon and Pero" (p. 128).

The book says that the fact that we can see the dirty desires towards women is proof that our society has changed.

He further rebukes them, saying that our society can only mature if we accept different interpretations of these women.

Women are not inferior beings, food, tools, or objects of voyeurism.

Part 3, “Women Have the Right to Safety,” examines the sexual oppression and violence experienced by women in paintings from the 16th to 18th centuries and asks how much has changed in this era.

It has been a long time since women's behavior was controlled with the absurd claim that 'men are beasts'.

In the early 16th century painting by Ambrosius Benson, Lucretia (p. 185), a woman attempts to take her own life after being sexually assaulted.

In 1736, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, in his painting The Broken Mirror (p. 177), portrayed a woman who had lost her chastity, portraying her as impulsive and driven to madness.

Both paintings attribute the cause of the incident to the female victim rather than the male perpetrator.

Artemisia Gentileschi is a painter who actively exposed her sexual assault and accused the perpetrator during these dark times.

In her “Self-Portrait” (page 189), in which she proclaims to the world that she is an artist, not a victim of sexual violence who must be “pitiful” as society wants, we can see her proud “survivor-likeness” rather than her “victim-likeness.”

(Page 188) In order to protect women's right to safety and to create such a society, we must say this.

“The price for committing a crime falls on the perpetrator.

“The perpetrator goes to prison, the victim goes back to everyday life.” (p. 190)

Part 4, “Women, We Are Ourselves,” is the story of women who proudly displayed their talents without being swayed by the times.

Pan Yuliang, the first female oil painter in China and the first Chinese to win an award at an Italian art exhibition; Anna Dorothea Terbusch, who wore glasses and read books to show off her intellectual side, in short, painted self-portraits claiming to be a figure that men disliked; and Mary Moser and Georgia O'Keeffe, who proudly showed off their skills by painting pictures that were true to themselves.

Here we have gathered the stories of female artists who threw off the shackles imposed on women and lived their own lives.

On the other hand, it also captures the stories of women who wanted to live as themselves, such as Jane Eyre, George Sand, and Queen Christina, who could only display their talents by borrowing a man's name.

Now it's time to give them back their real names.

Mary Moser and Georgia O'Keeffe,

They didn't paint 'feminine' pictures.

I just drew a picture that was 'my own'

When we rebel against the stereotypes of women as interpreted by patriarchal society, we can see the true face of women.

Women Who Torn the Canvas offers a perverse sense of the women found in paintings from the past century.

Because you have to be able to see things crookedly to discover the true sense.

Only then can we say that it is not the martyrdom of women, but the suffering of women, and not the devotion of women, but the despair and sorrow of women.

The author wrote this book in the hope that the patriarchal society, which cleverly tries to protect the sexual play of women with beauty and purity, will one day be shattered (p. 125).

Now women have taken the 'red pill' (p. 125) from the matrix of patriarchal society.

It is irreversible.

So, watch the women walk out of the painting with strength and clap your hands until your palms hurt.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: December 16, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 296 pages | 410g | 135*195*17mm

- ISBN13: 9791160404494

- ISBN10: 1160404496

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)