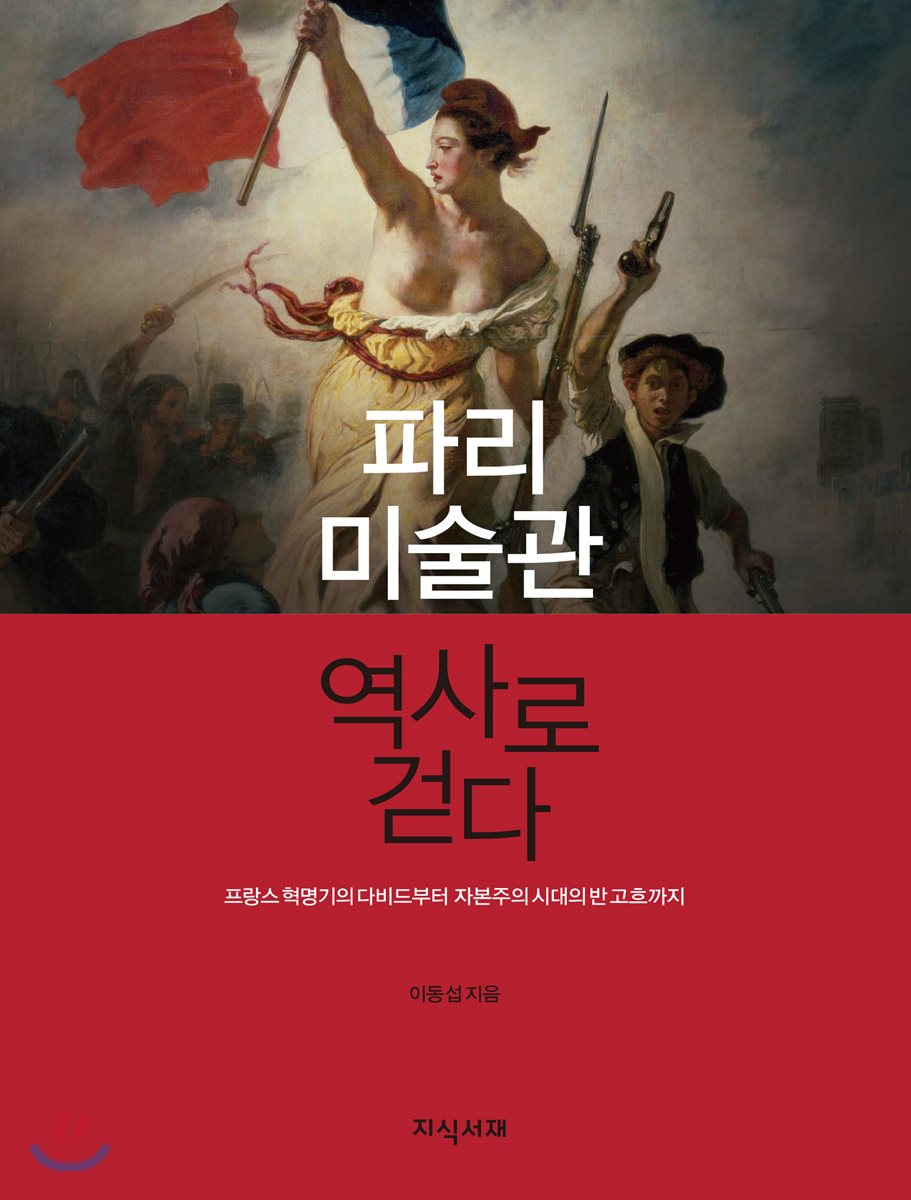

Walking through the history of Paris art museums

|

Description

Book Introduction

Encounter French History at the Louvre and the Musée d'Orsay Paris, France, is a city of romance and art, as well as a city of freedom and revolution. This unique image of Paris was created because of the French Revolution of 1789 and the civil society that was formed on its basis, allowing various arts and cultures to flourish freely. Through the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, the rise of Napoleon, the First Empire, the Second Empire, the Paris Commune, and the Third Republic, a civil society advocating liberty, equality, and fraternity was established in France. This arduous journey of history is fully reflected in the collections of Parisian art museums. David, an opportunist who survived by changing his supporters with each monarchy, revolution, and establishment; Delacroix, who captured the revolution on canvas; Millet and Courbet, who depicted peasants, workers, and the lower classes who were granted the right to vote in the new era; Manet, who became a star through scandal in the popular era; Monet, who depicted ordinary daily life instead of revolution; Renoir, who depicted Paris reborn as a modern city; Van Gogh, who fell victim to the cruelty of early capitalist society; Rousseau, who succeeded as a Sunday painter in an era when workers were guaranteed weekend rest… Their paintings contain traces of French history. 『Walking through the History of Parisian Art Museums』 is a humanities + arts + travel book that kindly tells the history of France through paintings from art museums in Paris (and nearby areas), including the Louvre, Orsay, Orangerie, Petit Palais, Rodin, Marmottan Monet, and the Palace of Versailles. As you take a picture tour, you will soon gain an easy and deep understanding of modern and contemporary French history. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Entering

01 David and the French Revolution: Genius Painter or Cunning Opportunist?

02 David and Napoleon: “I dedicate this painting to the Emperor.”

03 Delacroix and the Bourbon Dynasty: Rebellion against Past Authority

04 Millet and the Beginning of Universal Suffrage: Making Peasants the Protagonists of Painting

05 Courbet and the Second Empire: Painting Workers and the Lower Class

06 Manet and the Popular Era: Stars Are Born from Scandal

07 After Degas and the Paris Commune: Back to Everyday Life

08 Monet and the Third Republic: Completing the Revolution in Painting

09 Renoir and the Modern City of Paris: Painting French Romanticism

10 Cézanne and the Republican Era: The Murder of Da Vinci

11 Van Gogh and Capitalism: The Creation of a New Human Type

12 Rousseau and the Age of Equality: Anyone Can Be a Painter

Appendix 1: Map of Parisian art museums and their major collections

Appendix 2: Timeline of Major French Events and Art

01 David and the French Revolution: Genius Painter or Cunning Opportunist?

02 David and Napoleon: “I dedicate this painting to the Emperor.”

03 Delacroix and the Bourbon Dynasty: Rebellion against Past Authority

04 Millet and the Beginning of Universal Suffrage: Making Peasants the Protagonists of Painting

05 Courbet and the Second Empire: Painting Workers and the Lower Class

06 Manet and the Popular Era: Stars Are Born from Scandal

07 After Degas and the Paris Commune: Back to Everyday Life

08 Monet and the Third Republic: Completing the Revolution in Painting

09 Renoir and the Modern City of Paris: Painting French Romanticism

10 Cézanne and the Republican Era: The Murder of Da Vinci

11 Van Gogh and Capitalism: The Creation of a New Human Type

12 Rousseau and the Age of Equality: Anyone Can Be a Painter

Appendix 1: Map of Parisian art museums and their major collections

Appendix 2: Timeline of Major French Events and Art

Detailed image

Into the book

Six years after "The Wounded Man," Courbet turned the Salon upside down with a painting in a completely different style.

It is “The Funeral at Ornans.”

…the title at the time of submission to the Salon was “Pictures of Historical People at the Funeral at Ornans.”

By depicting ordinary people from a rural village and then claiming they are historical figures, it seems like a more blatant rebellion against conventional painting than Millet's peasant paintings.

“Now is the age of ordinary people, so I will record even ordinary people from the countryside as historical figures.

“I will vividly express their voices through my paintings.” In this way, Courbet created a completely new kind of painting.

It's realism.

[Pages 134-142]

Since the Renaissance, perspective has been believed to represent the world realistically.

But we do not see real landscapes as if they were paintings with perspective.

Perspective, in which the world converges to a vanishing point, fixes the viewpoint to one place, so the painting contains only one viewpoint and landscape.

But our eyes keep moving here and there when we look at a landscape.

From each point of view, the object appears large even though it is far away, as if it were a close-up.

By summing up these various points of view, we create memories of a landscape.

So, a landscape organized according to perspective is a fictional landscape.

[Page 183]

"Star" is one of Degas' most popular pastel paintings.

…The title is “A Brightly Shining Star,” but the stage where the stars twinkled was not all that beautiful.

The man in the black suit on the upper left of the stage is a sponsor.

At that time, you could pay a dancer to meet her privately, and such meetings often led to prostitution.

In other paintings of dancers, older women are occasionally seen, either as go-betweens who arrange such encounters or as family members trying to protect their daughters from their seductions.

We see the beauty of the pure white ballerina, but the man whose face is hidden will see the girl as an object of sexual desire.

We feel beauty through ballerinas, but the reality of the girl who conveys that beauty is miserable.

It's a terrifyingly scary picture.

[Page 214]

Montmartre, where people dance to music, was the scene of a massacre five years ago.

In the spring of 1871, the leaders of the Paris Commune, who had taken up residence on the hill of Montmartre, fought fiercely against French government forces and allied forces, but were brutally massacred.

…In the five years since then, Paris and its citizens have changed completely.

In the new city of Paris, traces of the struggle were erased, and smartly dressed people strolled the city, enjoying shopping and entertainment.

The bloody past is gone, and the light present has arrived.

In the Third Republic, the message of moving beyond conflict and struggle to a new era of hope resonated deeply with the people.

The 'Revolution Square' where the guillotine was installed was hastily renamed 'Place de la Concorde', meaning harmony, to cover up the blood of the countless lives lost there.

[Pages 293-295]

The biggest dilemma for 19th-century artists, during which Van Gogh was active, was the hegemony of the market.

As creators and sellers of paintings, they were unable to seize control of the market.

Without a market, the possibility of selling a painting would be completely blocked, so a market was necessary, but the duality of rejecting the logic of the market had to be endured.

Here we encounter our modern lives.

We live in a neoliberal society that is even more cold-hearted than the capitalism of the early 19th century. In order to do what we want, we have to do things we don't want to do.

If you live like that, the things you wanted to do will gradually become distant and blurry, like last night's dream.

[Page 365]

It is “The Funeral at Ornans.”

…the title at the time of submission to the Salon was “Pictures of Historical People at the Funeral at Ornans.”

By depicting ordinary people from a rural village and then claiming they are historical figures, it seems like a more blatant rebellion against conventional painting than Millet's peasant paintings.

“Now is the age of ordinary people, so I will record even ordinary people from the countryside as historical figures.

“I will vividly express their voices through my paintings.” In this way, Courbet created a completely new kind of painting.

It's realism.

[Pages 134-142]

Since the Renaissance, perspective has been believed to represent the world realistically.

But we do not see real landscapes as if they were paintings with perspective.

Perspective, in which the world converges to a vanishing point, fixes the viewpoint to one place, so the painting contains only one viewpoint and landscape.

But our eyes keep moving here and there when we look at a landscape.

From each point of view, the object appears large even though it is far away, as if it were a close-up.

By summing up these various points of view, we create memories of a landscape.

So, a landscape organized according to perspective is a fictional landscape.

[Page 183]

"Star" is one of Degas' most popular pastel paintings.

…The title is “A Brightly Shining Star,” but the stage where the stars twinkled was not all that beautiful.

The man in the black suit on the upper left of the stage is a sponsor.

At that time, you could pay a dancer to meet her privately, and such meetings often led to prostitution.

In other paintings of dancers, older women are occasionally seen, either as go-betweens who arrange such encounters or as family members trying to protect their daughters from their seductions.

We see the beauty of the pure white ballerina, but the man whose face is hidden will see the girl as an object of sexual desire.

We feel beauty through ballerinas, but the reality of the girl who conveys that beauty is miserable.

It's a terrifyingly scary picture.

[Page 214]

Montmartre, where people dance to music, was the scene of a massacre five years ago.

In the spring of 1871, the leaders of the Paris Commune, who had taken up residence on the hill of Montmartre, fought fiercely against French government forces and allied forces, but were brutally massacred.

…In the five years since then, Paris and its citizens have changed completely.

In the new city of Paris, traces of the struggle were erased, and smartly dressed people strolled the city, enjoying shopping and entertainment.

The bloody past is gone, and the light present has arrived.

In the Third Republic, the message of moving beyond conflict and struggle to a new era of hope resonated deeply with the people.

The 'Revolution Square' where the guillotine was installed was hastily renamed 'Place de la Concorde', meaning harmony, to cover up the blood of the countless lives lost there.

[Pages 293-295]

The biggest dilemma for 19th-century artists, during which Van Gogh was active, was the hegemony of the market.

As creators and sellers of paintings, they were unable to seize control of the market.

Without a market, the possibility of selling a painting would be completely blocked, so a market was necessary, but the duality of rejecting the logic of the market had to be endured.

Here we encounter our modern lives.

We live in a neoliberal society that is even more cold-hearted than the capitalism of the early 19th century. In order to do what we want, we have to do things we don't want to do.

If you live like that, the things you wanted to do will gradually become distant and blurry, like last night's dream.

[Page 365]

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

Enjoying in Paris, France

Art + History + Travel

An exciting collaboration!

The Hidden History of Parisian Art Museums

There is a place that travelers visiting Paris, France must visit.

These are the Louvre and the Orsay Museum.

If you visit the Palace of Versailles, the French History Museum located there is also a must-see.

As you walk along the long line of visitors, you may come across some familiar works of art.

Examples include [Liberty Leading the People], [Napoleon Crossing the Saint-Bernard Gorge in the Alps], [The Angelus], [Water Lilies], and Van Gogh's [Self-Portrait].

The collections found in Paris (and its surrounding areas)—the Louvre, the Musée d'Orsay, the Orangerie, the Petit Palais, Rodin, Marmottan Monet, and the Musée d'Histoire de France at the Palace of Versailles—serve as messengers of France's long history, telling us about it today.

In particular, it vividly depicts the turbulent process of change from the French Revolution of 1789, which fundamentally changed French society, to the era of capitalism.

Lee Dong-seop, an art humanist who has long been active in explaining humanities through works of art, makes a novel and interesting attempt to understand the French Revolution and history through paintings in Parisian art museums in his book, “Walking Through the History of Parisian Art Museums.”

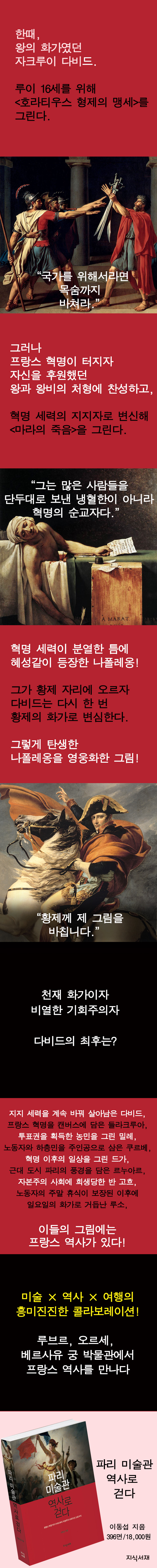

From King to Revolutionary, and then to Napoleon: The Last of David

Jacques-Louis David was a neoclassical painter who was so outstanding that he was praised as a genius.

Even if the name is unfamiliar, if you say that you painted a picture of Napoleon crossing the Alps on a white horse, everyone will exclaim, "Ah."

He is a painter who is familiar to us even today.

But at the same time, he has been accused of being a despicable opportunist.

During the reign of Louis XVI, he served as the king's painter and painted the [Oath of the Horatii], which contained a message of loyalty to the country, even at the cost of one's life. However, during the French Revolution, he voted in favor of executing his patron, Louis XVI, and his wife, Marie Antoinette.

David's journey doesn't stop there.

He even shows his loyalty to the revolutionary forces by writing [The Death of Marat], which depicts the revolutionary's last moments.

However, with the split in the revolutionary forces, the Thermidorian Reaction occurred, and with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte to power following a coup and an uprising, David was once again resurrected (or changed his mind) as the emperor's painter.

The decisive evidence is [the Emperor's Coronation].

At his coronation as emperor at Notre Dame Cathedral in 1804, Napoleon committed the blasphemy of taking the crown from Pope Pius VII's hands and placing it on his own head.

David, who was in the difficult situation of having to paint this scene, escaped the crisis by painting the moment when Napoleon crowned Empress Josephine.

David, who continued to be favored by the emperor for painting paintings that suited his taste, was driven into a corner when Napoleon failed in the blockade of England and the Russian expedition and fell from power.

David wanted to go into exile in Rome, but the Pope, who had suffered humiliation at his coronation, would not allow it.

Eventually, David went into exile in Brussels, Belgium, where he died.

The French Revolution on Canvas: Delacroix's Revolt

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, changed almost everything in France, including its political system, society, and culture.

Art was no exception.

The most famous painting depicting the French Revolution is Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People.

Marianne, in the center of the screen, leads the people across the barricades, holding the tricolor flag and a musket, symbolizing the spirit of the French Revolution.

Marian is not a real person, but the personification of freedom and reason, which all those who sacrificed their lives for noble values hoped would be realized in reality.

Neoclassical painters like David or Ingres would have depicted Marianne as an ancient Greek and Roman goddess, but the Romantic painter Delacroix painted her as an ordinary Parisian girl with her hair tied back.

Louis Philippe, who ascended to the throne after the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, and the First Empire, bought this painting for 3,000 francs and exhibited it at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts.

However, each time the museum director changed, out of fear that it would provoke the riotous sentiments of Parisian citizens, the painting was repeatedly moved between storage and exhibition hall.

Then, starting in 1874, after the Third Republic and the end of the French Revolution, it was permanently exhibited at the Louvre Museum.

The situation in the painting is closely linked to the domestic political situation in France.

Painting Peasants and Workers Who Gained the Right to Vote: The Choices of Millet and Courbet

The monarchy of Louis Philippe, who came to power through the July Revolution, was a bourgeois kingdom.

By easing the conditions for voting and being elected, the right to vote was expanded, and the interests of the bourgeoisie were openly represented.

As the socialist movement to eliminate the gap between rich and poor caused by income inequality was spreading throughout society, the government faced a financial crisis as crop failures, skyrocketing prices, a recession, falling wages, a surge in unemployment, and a stock market crash continued.

The dire economic situation and the incompetence of Louis Philippe led to the February Revolution of 1848, and the king, defeated by the citizen army, went into exile.

The February Revolution was a victory for the workers and the common people.

After ending the monarchy, France chose a republic (Second Republic) again.

When the right to vote was granted to all men over the age of 21, regardless of economic power, farmers and workers, who had lower incomes but were more numerous than the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, came to be recognized as an important group for social change.

During this period, Jean-François Millet painted peasants in the Barbizon countryside, and Gustave Courbet painted workers and the lower classes of industrial society.

The farmer in Millet's [The Angelus] is an honest and noble being who lives diligently every day without blaming the environment or the world.

The common people of the rural village depicted in Courbet's [Funeral at Ornans] are 'ordinary people' who have newly emerged as historical protagonists.

Capturing Ordinary Life After the Paris Commune: The Choices of Degas and Renoir

Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon), who was the president of the Second Republic, staged a coup in 1851, ascended to the throne as emperor, and established the Second Empire.

However, he was deposed after losing the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

The provisional government signed a humiliating armistice with Prussian Prime Minister Bismarck.

In response, the citizens of Paris formed their own government, which became the Paris Commune.

The Paris Commune announced worker-centered policies, but was ultimately crushed by a brutal massacre by the allied French and Prussian forces.

After the Paris Commune, ordinary young people living in the Third Republic wanted to end the endless war and political struggle and live peacefully doing what they wanted.

I began to find meaning in ordinary daily life rather than in grand ideologies.

Like the minds of the French people at the time, who had just come out of a long period of turmoil, Degas's paintings are apolitical, sophisticated, urban, and modern.

The figures depicted in Degas's [Absinthe] and [Star] realistically show the reality and gloom of Paris in the late 19th century.

On the other hand, Renoir, 'the only master who never painted sad pictures', optimistically portrayed modern Parisians enjoying their holidays in [Ball at the Moulin de la Galette] and [Luncheon on a Boat].

After 1850, Paris underwent a process of modernization, including the spread of capitalism, industrialization, and technological innovation, and the life of a large city was formed.

Modern people discovered leisure loisir to enrich their lives, and meals, picnics, walks, boat rides, horse races, festivals, and theater attendance became part of daily life.

Renoir reflected this reality by painting poor workers in bright and cheerful ways.

The Light and Shadow of Capitalism and an Egalitarian Society: The Lives of Van Gogh and the Customs Officer Rousseau

Through monarchies, revolutions, several empires, and a republic, France established a civil society based on the spirit of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Painters also gained the freedom to paint what they wanted, rather than what the king or nobles demanded.

But this freedom wasn't free.

The very important question that remained was who would buy the artists' paintings.

The artist had to solve two difficult questions simultaneously: creating and selling.

The republic established by the French Revolution was ultimately a society for the bourgeoisie, and those who ran counter to their capitalist worldview were punished as useless.

It is at this very point that the suffering of Van Gogh, who lived in early capitalism, resonates with the hearts of people living in capitalism today.

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam houses the palette that Van Gogh used. The dried paint that he could not use makes it seem like a self-portrait of him who died before he could live his life.

Vincent van Gogh's untimely death has become a symbol of the discord between dreams and reality for those living in capitalism.

On the other hand, there were painters who worked steadily on Sunday, the workers' day of rest obtained as a result of the French Revolution, and opened up a surprisingly fascinating world.

Henri Rousseau, also called 'Customs Officer Rousseau' to distinguish him from the philosopher Rousseau.

He taught himself to paint while working as a low-ranking customs official in Paris, so his skills were clumsy, but because of this, he acquired an originality that even Picasso recognized.

Overcoming the sarcasm and criticism that he was a 'bad painter', he is now an immortal painter with his own room in the Musee d'Orsay.

The charm of Paris began with the spirit of the French Revolution.

The spirit of liberty, equality, and fraternity put forward by the French Revolution of 1789 changed not only French politics and society, but also culture, art, and almost everything else.

This is why Paris is loved by people all over the world today.

The appeal of Paris, the 'cultural capital', was possible because it broadly accepted the diverse personalities of artists.

If we lose it, Paris will lose its charm.

Impressionism, as both its origin and its outcome, is France's greatest export.

While the influence of the Palace of Versailles, built by Louis XIV, was limited to a part of Europe, Impressionism, represented by the Musee d'Orsay and the Musee de l'Orangerie, exerted its power as a symbol of French culture throughout the world.

"Walking Through the History of Parisian Art Museums" follows the footsteps of French history through paintings found in Paris and tells us its stories.

As you journey through the pictures with this book, you will soon gain an easy and profound understanding of French history and culture.

[Related Naver Post] http://naver.me/5c5VICUV

#0.

Starting the series

#1.

"I present my painting to the Emperor" The end of the traitor David

#2.

"The French Revolution Changed Everything" Delacroix's Revolt

#3.

"Painting a Peasant Who Gains the Right to Vote" Millet's Choice

#4.

Courbet's choice: "Portray the lower classes, the protagonists of a new era."

#5.

Manet's notoriety: "Becoming a star of the popular era through scandal"

#6.

"Now let's end the revolution and return to normal life." Degas' choice.

#7.

"A new era paints with new techniques" - Monet's brushstrokes

#8.

"Life is Beautiful" Renoir, who loved the modern city of Paris

#9.

"A Victim of the Cruelty of Capitalism": Van Gogh's Life

#10.

"Workers Can Be Painters Too": The Rebellion of Customs Officer Rousseau

Art + History + Travel

An exciting collaboration!

The Hidden History of Parisian Art Museums

There is a place that travelers visiting Paris, France must visit.

These are the Louvre and the Orsay Museum.

If you visit the Palace of Versailles, the French History Museum located there is also a must-see.

As you walk along the long line of visitors, you may come across some familiar works of art.

Examples include [Liberty Leading the People], [Napoleon Crossing the Saint-Bernard Gorge in the Alps], [The Angelus], [Water Lilies], and Van Gogh's [Self-Portrait].

The collections found in Paris (and its surrounding areas)—the Louvre, the Musée d'Orsay, the Orangerie, the Petit Palais, Rodin, Marmottan Monet, and the Musée d'Histoire de France at the Palace of Versailles—serve as messengers of France's long history, telling us about it today.

In particular, it vividly depicts the turbulent process of change from the French Revolution of 1789, which fundamentally changed French society, to the era of capitalism.

Lee Dong-seop, an art humanist who has long been active in explaining humanities through works of art, makes a novel and interesting attempt to understand the French Revolution and history through paintings in Parisian art museums in his book, “Walking Through the History of Parisian Art Museums.”

From King to Revolutionary, and then to Napoleon: The Last of David

Jacques-Louis David was a neoclassical painter who was so outstanding that he was praised as a genius.

Even if the name is unfamiliar, if you say that you painted a picture of Napoleon crossing the Alps on a white horse, everyone will exclaim, "Ah."

He is a painter who is familiar to us even today.

But at the same time, he has been accused of being a despicable opportunist.

During the reign of Louis XVI, he served as the king's painter and painted the [Oath of the Horatii], which contained a message of loyalty to the country, even at the cost of one's life. However, during the French Revolution, he voted in favor of executing his patron, Louis XVI, and his wife, Marie Antoinette.

David's journey doesn't stop there.

He even shows his loyalty to the revolutionary forces by writing [The Death of Marat], which depicts the revolutionary's last moments.

However, with the split in the revolutionary forces, the Thermidorian Reaction occurred, and with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte to power following a coup and an uprising, David was once again resurrected (or changed his mind) as the emperor's painter.

The decisive evidence is [the Emperor's Coronation].

At his coronation as emperor at Notre Dame Cathedral in 1804, Napoleon committed the blasphemy of taking the crown from Pope Pius VII's hands and placing it on his own head.

David, who was in the difficult situation of having to paint this scene, escaped the crisis by painting the moment when Napoleon crowned Empress Josephine.

David, who continued to be favored by the emperor for painting paintings that suited his taste, was driven into a corner when Napoleon failed in the blockade of England and the Russian expedition and fell from power.

David wanted to go into exile in Rome, but the Pope, who had suffered humiliation at his coronation, would not allow it.

Eventually, David went into exile in Brussels, Belgium, where he died.

The French Revolution on Canvas: Delacroix's Revolt

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, changed almost everything in France, including its political system, society, and culture.

Art was no exception.

The most famous painting depicting the French Revolution is Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People.

Marianne, in the center of the screen, leads the people across the barricades, holding the tricolor flag and a musket, symbolizing the spirit of the French Revolution.

Marian is not a real person, but the personification of freedom and reason, which all those who sacrificed their lives for noble values hoped would be realized in reality.

Neoclassical painters like David or Ingres would have depicted Marianne as an ancient Greek and Roman goddess, but the Romantic painter Delacroix painted her as an ordinary Parisian girl with her hair tied back.

Louis Philippe, who ascended to the throne after the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, and the First Empire, bought this painting for 3,000 francs and exhibited it at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts.

However, each time the museum director changed, out of fear that it would provoke the riotous sentiments of Parisian citizens, the painting was repeatedly moved between storage and exhibition hall.

Then, starting in 1874, after the Third Republic and the end of the French Revolution, it was permanently exhibited at the Louvre Museum.

The situation in the painting is closely linked to the domestic political situation in France.

Painting Peasants and Workers Who Gained the Right to Vote: The Choices of Millet and Courbet

The monarchy of Louis Philippe, who came to power through the July Revolution, was a bourgeois kingdom.

By easing the conditions for voting and being elected, the right to vote was expanded, and the interests of the bourgeoisie were openly represented.

As the socialist movement to eliminate the gap between rich and poor caused by income inequality was spreading throughout society, the government faced a financial crisis as crop failures, skyrocketing prices, a recession, falling wages, a surge in unemployment, and a stock market crash continued.

The dire economic situation and the incompetence of Louis Philippe led to the February Revolution of 1848, and the king, defeated by the citizen army, went into exile.

The February Revolution was a victory for the workers and the common people.

After ending the monarchy, France chose a republic (Second Republic) again.

When the right to vote was granted to all men over the age of 21, regardless of economic power, farmers and workers, who had lower incomes but were more numerous than the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, came to be recognized as an important group for social change.

During this period, Jean-François Millet painted peasants in the Barbizon countryside, and Gustave Courbet painted workers and the lower classes of industrial society.

The farmer in Millet's [The Angelus] is an honest and noble being who lives diligently every day without blaming the environment or the world.

The common people of the rural village depicted in Courbet's [Funeral at Ornans] are 'ordinary people' who have newly emerged as historical protagonists.

Capturing Ordinary Life After the Paris Commune: The Choices of Degas and Renoir

Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon), who was the president of the Second Republic, staged a coup in 1851, ascended to the throne as emperor, and established the Second Empire.

However, he was deposed after losing the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

The provisional government signed a humiliating armistice with Prussian Prime Minister Bismarck.

In response, the citizens of Paris formed their own government, which became the Paris Commune.

The Paris Commune announced worker-centered policies, but was ultimately crushed by a brutal massacre by the allied French and Prussian forces.

After the Paris Commune, ordinary young people living in the Third Republic wanted to end the endless war and political struggle and live peacefully doing what they wanted.

I began to find meaning in ordinary daily life rather than in grand ideologies.

Like the minds of the French people at the time, who had just come out of a long period of turmoil, Degas's paintings are apolitical, sophisticated, urban, and modern.

The figures depicted in Degas's [Absinthe] and [Star] realistically show the reality and gloom of Paris in the late 19th century.

On the other hand, Renoir, 'the only master who never painted sad pictures', optimistically portrayed modern Parisians enjoying their holidays in [Ball at the Moulin de la Galette] and [Luncheon on a Boat].

After 1850, Paris underwent a process of modernization, including the spread of capitalism, industrialization, and technological innovation, and the life of a large city was formed.

Modern people discovered leisure loisir to enrich their lives, and meals, picnics, walks, boat rides, horse races, festivals, and theater attendance became part of daily life.

Renoir reflected this reality by painting poor workers in bright and cheerful ways.

The Light and Shadow of Capitalism and an Egalitarian Society: The Lives of Van Gogh and the Customs Officer Rousseau

Through monarchies, revolutions, several empires, and a republic, France established a civil society based on the spirit of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Painters also gained the freedom to paint what they wanted, rather than what the king or nobles demanded.

But this freedom wasn't free.

The very important question that remained was who would buy the artists' paintings.

The artist had to solve two difficult questions simultaneously: creating and selling.

The republic established by the French Revolution was ultimately a society for the bourgeoisie, and those who ran counter to their capitalist worldview were punished as useless.

It is at this very point that the suffering of Van Gogh, who lived in early capitalism, resonates with the hearts of people living in capitalism today.

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam houses the palette that Van Gogh used. The dried paint that he could not use makes it seem like a self-portrait of him who died before he could live his life.

Vincent van Gogh's untimely death has become a symbol of the discord between dreams and reality for those living in capitalism.

On the other hand, there were painters who worked steadily on Sunday, the workers' day of rest obtained as a result of the French Revolution, and opened up a surprisingly fascinating world.

Henri Rousseau, also called 'Customs Officer Rousseau' to distinguish him from the philosopher Rousseau.

He taught himself to paint while working as a low-ranking customs official in Paris, so his skills were clumsy, but because of this, he acquired an originality that even Picasso recognized.

Overcoming the sarcasm and criticism that he was a 'bad painter', he is now an immortal painter with his own room in the Musee d'Orsay.

The charm of Paris began with the spirit of the French Revolution.

The spirit of liberty, equality, and fraternity put forward by the French Revolution of 1789 changed not only French politics and society, but also culture, art, and almost everything else.

This is why Paris is loved by people all over the world today.

The appeal of Paris, the 'cultural capital', was possible because it broadly accepted the diverse personalities of artists.

If we lose it, Paris will lose its charm.

Impressionism, as both its origin and its outcome, is France's greatest export.

While the influence of the Palace of Versailles, built by Louis XIV, was limited to a part of Europe, Impressionism, represented by the Musee d'Orsay and the Musee de l'Orangerie, exerted its power as a symbol of French culture throughout the world.

"Walking Through the History of Parisian Art Museums" follows the footsteps of French history through paintings found in Paris and tells us its stories.

As you journey through the pictures with this book, you will soon gain an easy and profound understanding of French history and culture.

[Related Naver Post] http://naver.me/5c5VICUV

#0.

Starting the series

#1.

"I present my painting to the Emperor" The end of the traitor David

#2.

"The French Revolution Changed Everything" Delacroix's Revolt

#3.

"Painting a Peasant Who Gains the Right to Vote" Millet's Choice

#4.

Courbet's choice: "Portray the lower classes, the protagonists of a new era."

#5.

Manet's notoriety: "Becoming a star of the popular era through scandal"

#6.

"Now let's end the revolution and return to normal life." Degas' choice.

#7.

"A new era paints with new techniques" - Monet's brushstrokes

#8.

"Life is Beautiful" Renoir, who loved the modern city of Paris

#9.

"A Victim of the Cruelty of Capitalism": Van Gogh's Life

#10.

"Workers Can Be Painters Too": The Rebellion of Customs Officer Rousseau

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: December 13, 2018

- Page count, weight, size: 396 pages | 630g | 152*200*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791196128975

- ISBN10: 1196128979

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)