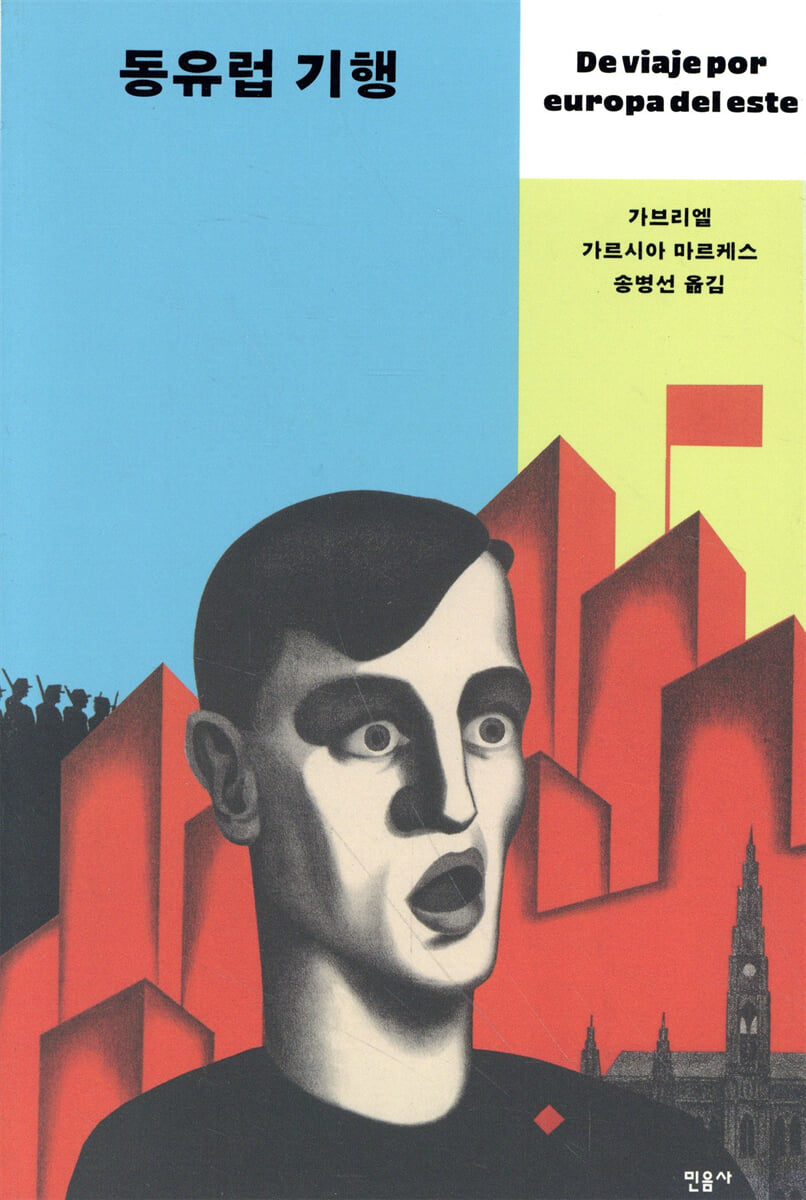

Eastern European travelogue

|

Description

Book Introduction

Proletarians of the world, unite!?

Marquez, a novelist, journalist and South America's greatest satirist

A socialist travelogue filled with sharp wit and hilarious humor, written with honesty and candor.

Colombian Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez has published a travel essay, "Travels in Eastern Europe," which contains stories of his experiences while traveling through Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the late 1950s, when the Iron Curtain had just fallen.

Marquez, a young writer and journalist living in West Germany, was driving a used car that a friend had bought by chance, and he was having a blast on the Autobahn.

Then one day, in a bar in Frankfurt, he suddenly feels the urge to visit East Germany, and Marquez and his cheerful friends 'play crazy' and cross the East German border behind the Iron Curtain.

This coincidence soon led to the inevitable 'World Youth Festival' held in Moscow, and the articles and records left by Marquez while traveling through Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were compiled into a book.

Marquez, a novelist, journalist and South America's greatest satirist

A socialist travelogue filled with sharp wit and hilarious humor, written with honesty and candor.

Colombian Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez has published a travel essay, "Travels in Eastern Europe," which contains stories of his experiences while traveling through Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the late 1950s, when the Iron Curtain had just fallen.

Marquez, a young writer and journalist living in West Germany, was driving a used car that a friend had bought by chance, and he was having a blast on the Autobahn.

Then one day, in a bar in Frankfurt, he suddenly feels the urge to visit East Germany, and Marquez and his cheerful friends 'play crazy' and cross the East German border behind the Iron Curtain.

This coincidence soon led to the inevitable 'World Youth Festival' held in Moscow, and the articles and records left by Marquez while traveling through Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were compiled into a book.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

The 'Iron Curtain' was a red and white painted wooden fence.

Berlin, the epitome of absurdity 25

The expropriated gather to share their suffering 41

Nylon stockings are like jewels to Czech women. 63

In Prague, people react like people in all capitalist countries. 83

103 Looking at Poland with eyes wide open and seething

Soviet Union: 143 places in 22.4 million square kilometers without a single Coca-Cola billboard

Moscow: The World's Largest Town 163

In the mausoleum on Red Square, Stalin sleeps without a guilty conscience. 185

Soviet people are starting to tire of polarization 211

“I went to Hungary and saw it” 227

Berlin, the epitome of absurdity 25

The expropriated gather to share their suffering 41

Nylon stockings are like jewels to Czech women. 63

In Prague, people react like people in all capitalist countries. 83

103 Looking at Poland with eyes wide open and seething

Soviet Union: 143 places in 22.4 million square kilometers without a single Coca-Cola billboard

Moscow: The World's Largest Town 163

In the mausoleum on Red Square, Stalin sleeps without a guilty conscience. 185

Soviet people are starting to tire of polarization 211

“I went to Hungary and saw it” 227

Into the book

The 'Iron Curtain' is neither a curtain nor made of iron.

It's a wooden fence painted red and white, just like a barbershop sign.

After living inside that curtain for three months, I realized that hoping the Iron Curtain was really an Iron Curtain was a lack of common sense.

--- p.9

The two soldiers copied the information in our passports using the nib of a quill and ink from a corked ink bottle.

I worked very hard.

As one soldier read, the other soldier wrote down the sounds of French, Italian, and Spanish in the rudimentary handwriting of someone who had only attended a rural elementary school.

His fingers were covered in ink.

We were all sweating bullets.

They did it because they were trying hard, and we did it because they were trying hard.

--- p.14

“It’s okay if you don’t give me anything.

But I wish we could say what we want to say.” Surprised by this unanimous rebellion, I remembered that in the recent election, 92 percent of people voted in favor of the government.

Mr. Wolf laughed, holding his stomach, and pounded his chest with his hand as he said:

“I also voted in favor of the government.”

--- p.53

He also unconsciously warned me to be careful with my passport in Poland, which surprised me.

He explained to me.

“Poles are not communists.

They say yes, but they go to mass every Sunday.”

--- p.95

As Gomuuka came to power and the country began to enjoy freedom of expression, the court case against the Palace of Culture began, and that case is still ongoing.

At a protest a few weeks ago, Gomuuka was asked:

“Is the Palace of Culture a gift from the Soviet Union?” Gomuuka tries not to confront this question.

“That’s right,” he replied, and then struck the player to prevent any malicious comments from being made.

“You don’t look into the teeth of a horse you received as a gift.”

--- p.119

The laboratory where human derivatives were produced still remains.

Living people came in through one door, and human remains came out through the other.

Inside it remained everything that made up the raw material of a person.

Thus, the human leather industry, the human hair industry, and the human fat by-product industry were created.

In Austria I saw a huge pine-shaped soap sculpture decorated with flowers.

There was ample reason for someone to think that this soap was their uncle.

--- p.136

A young man from Murmansk probably saved all year to make the five-day journey by train.

He stopped us on the street and asked us:

“Do you speak English?”

That was the only English he knew.

--- p.177

He was a fat, old man, with a red, drunken nose and wire-meshed glasses.

When I told him I spoke English, he repeated something over and over again, but I couldn't understand what he meant.

He seemed to be in despair.

When we reached the end of the line and it was time for me to get off, he handed me a piece of paper on which were written in English the words, “God save Hungary.”

It's a wooden fence painted red and white, just like a barbershop sign.

After living inside that curtain for three months, I realized that hoping the Iron Curtain was really an Iron Curtain was a lack of common sense.

--- p.9

The two soldiers copied the information in our passports using the nib of a quill and ink from a corked ink bottle.

I worked very hard.

As one soldier read, the other soldier wrote down the sounds of French, Italian, and Spanish in the rudimentary handwriting of someone who had only attended a rural elementary school.

His fingers were covered in ink.

We were all sweating bullets.

They did it because they were trying hard, and we did it because they were trying hard.

--- p.14

“It’s okay if you don’t give me anything.

But I wish we could say what we want to say.” Surprised by this unanimous rebellion, I remembered that in the recent election, 92 percent of people voted in favor of the government.

Mr. Wolf laughed, holding his stomach, and pounded his chest with his hand as he said:

“I also voted in favor of the government.”

--- p.53

He also unconsciously warned me to be careful with my passport in Poland, which surprised me.

He explained to me.

“Poles are not communists.

They say yes, but they go to mass every Sunday.”

--- p.95

As Gomuuka came to power and the country began to enjoy freedom of expression, the court case against the Palace of Culture began, and that case is still ongoing.

At a protest a few weeks ago, Gomuuka was asked:

“Is the Palace of Culture a gift from the Soviet Union?” Gomuuka tries not to confront this question.

“That’s right,” he replied, and then struck the player to prevent any malicious comments from being made.

“You don’t look into the teeth of a horse you received as a gift.”

--- p.119

The laboratory where human derivatives were produced still remains.

Living people came in through one door, and human remains came out through the other.

Inside it remained everything that made up the raw material of a person.

Thus, the human leather industry, the human hair industry, and the human fat by-product industry were created.

In Austria I saw a huge pine-shaped soap sculpture decorated with flowers.

There was ample reason for someone to think that this soap was their uncle.

--- p.136

A young man from Murmansk probably saved all year to make the five-day journey by train.

He stopped us on the street and asked us:

“Do you speak English?”

That was the only English he knew.

--- p.177

He was a fat, old man, with a red, drunken nose and wire-meshed glasses.

When I told him I spoke English, he repeated something over and over again, but I couldn't understand what he meant.

He seemed to be in despair.

When we reached the end of the line and it was time for me to get off, he handed me a piece of paper on which were written in English the words, “God save Hungary.”

--- p.238

Publisher's Review

Let's pretend to be crazy and try to get over it,

The iron curtain

In early 1954, twenty-seven-year-old Gabriel García Márquez began his career as a novelist while working as an editor at the newspaper El Espectador in Bogotá.

In July 1955, when the 'Conference of the Four Western European Powers' was held in Geneva, the newspaper dispatched García Márquez to Europe.

After the military dictatorship of Rojas Pinilla closed down El Espectador, García Márquez ended up staying in Europe.

Marquez and his friends had progressive leanings and fantasies about socialism, and so they were eager to visit Eastern Europe.

Moreover, the upheaval of 1956, a year earlier, with Khrushchev denouncing Stalin and the Soviet invasion of Hungary, had made them more interested in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, and they were determined to see and understand real socialism with their own eyes.

They started in Leipzig, stopping briefly in Heidelberg and Frankfurt.

And then we continued driving from Frankfurt to East Germany.

The record of the journey that began this way was left in the form of an article written by García Márquez.

These articles were published in the Colombian weekly Cromos and the Venezuelan weekly Moment as a special feature entitled "90 Days Behind the Iron Curtain."

The Venezuelan magazine mainly published articles about the Soviet Union and Hungary, while the Colombian magazine published articles about the Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries, excluding Hungary.

These articles were compiled into a book and first published in Colombia in 1978.

The book was titled "Travels in Socialist Countries: 90 Days Behind the Iron Curtain," and was a compilation of articles written during visits to East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the former Soviet Union, and Hungary.

In fact, it should be kept in mind that 『Travels in Eastern Europe』 is not just a novelist's work, but is written from the perspective of a journalist.

At the time of writing this article, Masques had published Rotten Leaves (1955), but the novel had not generated much of a stir, and so he was not a celebrity during his travels.

In Eastern European countries, he was unknown, which was both an advantage and a disadvantage for him.

Although he was not an official guest and had limited freedom of movement, this allowed him to observe the natural world of the people in greater detail.

Simple yet complex people who walk around the train platform in nicer pajamas (probably paid for by the government) than their regular clothes to show off to guests from the Western world, and say that this is their custom.

Marquez not only describes their appearance and daily life, such as their clothes and food, but also asks them big questions about life, such as simple yet sharp questions like, "Are you happy?"

Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union

Is it a people's paradise, or a surreal stage of totalitarianism?

The 'Iron Curtain' is neither a curtain nor made of iron.

It's a wooden fence painted red and white, just like a barbershop sign.

After staying in that curtain for three months, I hope that the iron curtain really is an iron curtain.

I realized that it was a result of a lack of common sense._From the text

This book, which begins with a sharp sentence like the one above, skillfully describes the characteristics of each Eastern European country in short sentences.

The material and spiritual confusion experienced by the people of East Berlin, where the political system changed just across the street; the high self-esteem of the Poles, who feel no confusion in their identity as devout Catholics and ardent socialists at the same time; Czechoslovakia, which holds fast to its practicality in a beautiful and bright environment no less than Western Europe; the Hungarians, who tremble in fear after being devastated by the Soviet attack, but still lively in the back alley bars; the people of the Soviet Union, who do not have a single Coca-Cola billboard in 2240 square kilometers and do not even understand the principles of advertising, the flower of capitalism.

The film depicts the bizarre reality they face, their silent compliance with the system, and the people's desperate yearning for truth and freedom, all in a poignant yet humorous way.

Even before he achieved fame as a writer, García Márquez observed Eastern Europeans, mingled with them, and demonstrated his journalistic qualities and keen insight by judging only what he saw and heard firsthand.

We can also examine his political stance and perspectives, which were at the beginning of his journey as a writer.

The young writer Marquez sharply testifies to the political reality of Europe divided into capitalist Western Europe and communist Eastern Europe, while conveying to readers through these strange, sad, and humorous writings the simple yet easy-to-forget fact that there were 'people' living there, whether in East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, or Hungary.

The iron curtain

In early 1954, twenty-seven-year-old Gabriel García Márquez began his career as a novelist while working as an editor at the newspaper El Espectador in Bogotá.

In July 1955, when the 'Conference of the Four Western European Powers' was held in Geneva, the newspaper dispatched García Márquez to Europe.

After the military dictatorship of Rojas Pinilla closed down El Espectador, García Márquez ended up staying in Europe.

Marquez and his friends had progressive leanings and fantasies about socialism, and so they were eager to visit Eastern Europe.

Moreover, the upheaval of 1956, a year earlier, with Khrushchev denouncing Stalin and the Soviet invasion of Hungary, had made them more interested in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, and they were determined to see and understand real socialism with their own eyes.

They started in Leipzig, stopping briefly in Heidelberg and Frankfurt.

And then we continued driving from Frankfurt to East Germany.

The record of the journey that began this way was left in the form of an article written by García Márquez.

These articles were published in the Colombian weekly Cromos and the Venezuelan weekly Moment as a special feature entitled "90 Days Behind the Iron Curtain."

The Venezuelan magazine mainly published articles about the Soviet Union and Hungary, while the Colombian magazine published articles about the Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries, excluding Hungary.

These articles were compiled into a book and first published in Colombia in 1978.

The book was titled "Travels in Socialist Countries: 90 Days Behind the Iron Curtain," and was a compilation of articles written during visits to East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the former Soviet Union, and Hungary.

In fact, it should be kept in mind that 『Travels in Eastern Europe』 is not just a novelist's work, but is written from the perspective of a journalist.

At the time of writing this article, Masques had published Rotten Leaves (1955), but the novel had not generated much of a stir, and so he was not a celebrity during his travels.

In Eastern European countries, he was unknown, which was both an advantage and a disadvantage for him.

Although he was not an official guest and had limited freedom of movement, this allowed him to observe the natural world of the people in greater detail.

Simple yet complex people who walk around the train platform in nicer pajamas (probably paid for by the government) than their regular clothes to show off to guests from the Western world, and say that this is their custom.

Marquez not only describes their appearance and daily life, such as their clothes and food, but also asks them big questions about life, such as simple yet sharp questions like, "Are you happy?"

Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union

Is it a people's paradise, or a surreal stage of totalitarianism?

The 'Iron Curtain' is neither a curtain nor made of iron.

It's a wooden fence painted red and white, just like a barbershop sign.

After staying in that curtain for three months, I hope that the iron curtain really is an iron curtain.

I realized that it was a result of a lack of common sense._From the text

This book, which begins with a sharp sentence like the one above, skillfully describes the characteristics of each Eastern European country in short sentences.

The material and spiritual confusion experienced by the people of East Berlin, where the political system changed just across the street; the high self-esteem of the Poles, who feel no confusion in their identity as devout Catholics and ardent socialists at the same time; Czechoslovakia, which holds fast to its practicality in a beautiful and bright environment no less than Western Europe; the Hungarians, who tremble in fear after being devastated by the Soviet attack, but still lively in the back alley bars; the people of the Soviet Union, who do not have a single Coca-Cola billboard in 2240 square kilometers and do not even understand the principles of advertising, the flower of capitalism.

The film depicts the bizarre reality they face, their silent compliance with the system, and the people's desperate yearning for truth and freedom, all in a poignant yet humorous way.

Even before he achieved fame as a writer, García Márquez observed Eastern Europeans, mingled with them, and demonstrated his journalistic qualities and keen insight by judging only what he saw and heard firsthand.

We can also examine his political stance and perspectives, which were at the beginning of his journey as a writer.

The young writer Marquez sharply testifies to the political reality of Europe divided into capitalist Western Europe and communist Eastern Europe, while conveying to readers through these strange, sad, and humorous writings the simple yet easy-to-forget fact that there were 'people' living there, whether in East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, or Hungary.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 31, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 244 pages | 266g | 128*188*14mm

- ISBN13: 9788937427244

- ISBN10: 8937427249

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)