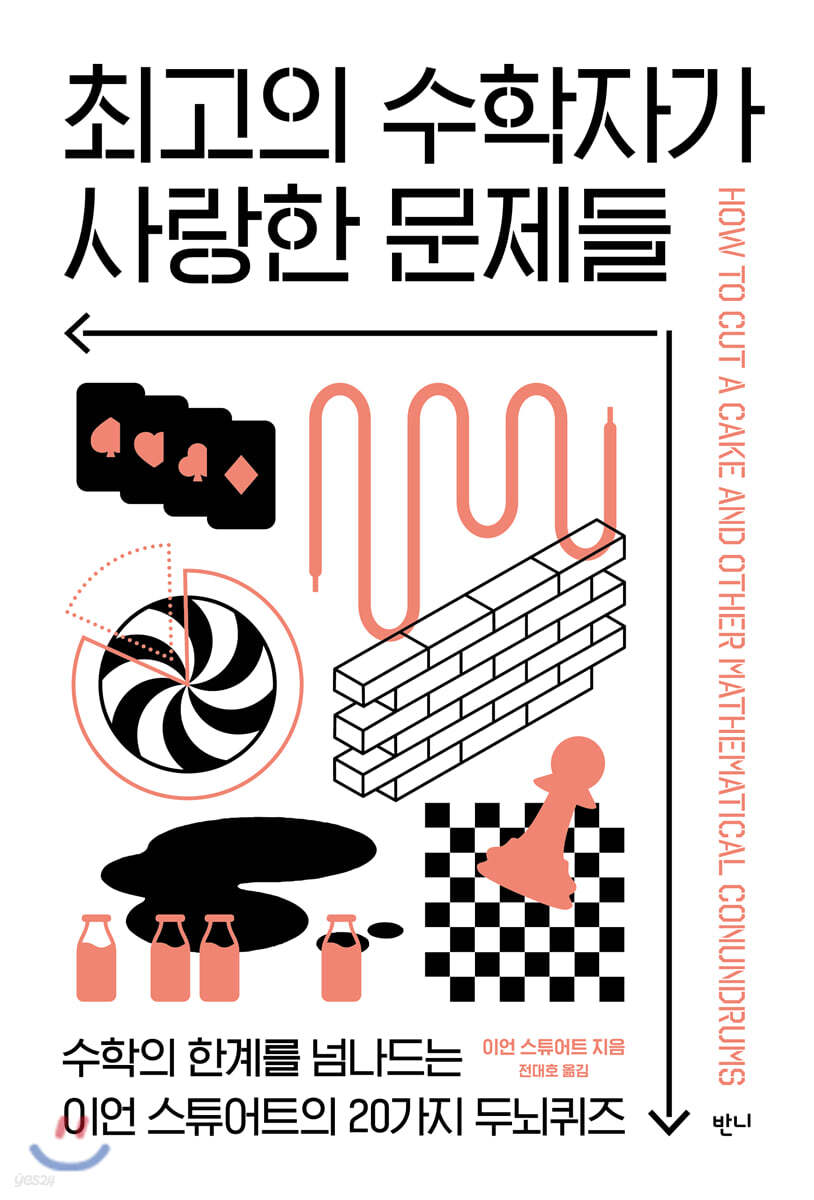

Problems Loved by the Greatest Mathematicians

|

Description

Book Introduction

“The best mathematics lies in strange universals.”

The cutting edge of math problems for those who enjoy extreme math.

For some, mathematics is a subject that brings pure terror, but for others, it is a language for understanding the world and a fun game.

Like the author of this book, Ian Stewart.

Stewart says mathematics is a source of inspiration and joy for him.

Of course, I also know that just as not everyone can understand a birdwatcher's passion for birds, not everyone can enjoy a passion for mathematics.

So, 『Problems Loved by the Best Mathematicians』 is a book for people who already know the appeal of mathematics and those who actively enjoy mathematics.

Ian Stewart invites readers into a world of 20 challenging math puzzles that will make math fun.

This book provides a glimpse into the ways in which mathematical geniuses view the world and solve problems, covering probability, statistics, geometry, topology, and graph theory.

Through 20 puzzles that have long stimulated the curiosity and inquisitiveness of mathematicians, readers can approach the core of modern mathematics in an easier and more engaging way.

The cutting edge of math problems for those who enjoy extreme math.

For some, mathematics is a subject that brings pure terror, but for others, it is a language for understanding the world and a fun game.

Like the author of this book, Ian Stewart.

Stewart says mathematics is a source of inspiration and joy for him.

Of course, I also know that just as not everyone can understand a birdwatcher's passion for birds, not everyone can enjoy a passion for mathematics.

So, 『Problems Loved by the Best Mathematicians』 is a book for people who already know the appeal of mathematics and those who actively enjoy mathematics.

Ian Stewart invites readers into a world of 20 challenging math puzzles that will make math fun.

This book provides a glimpse into the ways in which mathematical geniuses view the world and solve problems, covering probability, statistics, geometry, topology, and graph theory.

Through 20 puzzles that have long stimulated the curiosity and inquisitiveness of mathematicians, readers can approach the core of modern mathematics in an easier and more engaging way.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction / 5

Chapter 1 Your Half is Bigger than My Half! / 15

Chapter 2: Are the odds of flipping a coin fair? / 27

Chapter 3: Tying Your Shoes with the Shortest Laces / 45

Chapter 4: Simple but Tricky Paradoxes / 57

Chapter 5: Filling a Square Box with Round Milk Bottles / 71

Chapter 6: The Never-ending Chess Game / 87

Chapter 7: An Abstract Strategy Game of Creating Squares / 99

Chapter 8: The Protocol That Hides Me / 107

Chapter 9: Empires on the Moon / 117

Chapter 10: Empires and Electronics / 133

Chapter 11: Mix and Mix, Still in the Same Place / 149

Chapter 12: Double Bubbles, Hardships and Anxiety / 165

Chapter 13: The Tangled Railroad Tracks of the Brickyard / 181

Chapter 14: Jealousy-Free Cake Distribution / 193

Chapter 15: The Brightly Shining Fireflies / 205

Chapter 16: Why Are Telephone Cords Always Tangled? / 217

Chapter 17: Sierpinski's Triangles in Various Places / 231

Chapter 18: Defend the Roman Empire / 245

Chapter 19: Triangulation / 257

Chapter 20: Guessing the Date of Easter / 269

Feedback / 280

References / 292

Chapter 1 Your Half is Bigger than My Half! / 15

Chapter 2: Are the odds of flipping a coin fair? / 27

Chapter 3: Tying Your Shoes with the Shortest Laces / 45

Chapter 4: Simple but Tricky Paradoxes / 57

Chapter 5: Filling a Square Box with Round Milk Bottles / 71

Chapter 6: The Never-ending Chess Game / 87

Chapter 7: An Abstract Strategy Game of Creating Squares / 99

Chapter 8: The Protocol That Hides Me / 107

Chapter 9: Empires on the Moon / 117

Chapter 10: Empires and Electronics / 133

Chapter 11: Mix and Mix, Still in the Same Place / 149

Chapter 12: Double Bubbles, Hardships and Anxiety / 165

Chapter 13: The Tangled Railroad Tracks of the Brickyard / 181

Chapter 14: Jealousy-Free Cake Distribution / 193

Chapter 15: The Brightly Shining Fireflies / 205

Chapter 16: Why Are Telephone Cords Always Tangled? / 217

Chapter 17: Sierpinski's Triangles in Various Places / 231

Chapter 18: Defend the Roman Empire / 245

Chapter 19: Triangulation / 257

Chapter 20: Guessing the Date of Easter / 269

Feedback / 280

References / 292

Into the book

Different people assign different values to things in different situations.

Some people are very difficult to please.

For the past 50 years, mathematicians have wrestled with the problem of fair distribution.

There is now a comprehensive and surprisingly profound theory on the subject, which is usually discussed with cakes rather than fish.

--- pp.17~18, from “Your Half is Bigger than My Half”

People often talk about the 'law of averages'.

The basis is the intuition that if you flip a coin repeatedly, you should eventually get a consistent result.

Some even believe that in such cases, the chances of a comeback are higher.

We often think, “This time, it’s more likely to be the latter.”

Others assert that coins have no memory.

--- p.29, from “Are the odds of a coin toss fair?”

There are at least three common ways to tie your shoelaces.

See Figure 5.

These are the American zigzag tying, the European straight tying, and the quick tying, which is mainly used in shoe stores.

From a buyer's perspective, shoelace tying methods are differentiated by how attractive they are and how cumbersome they are.

But the more important question from the producer's point of view is which method has the shortest string (which method is the cheapest).

--- p.48, from “Tying Your Shoes with the Shortest Laces”

Mathematics interests people for at least three reasons.

First, math is fun (which is the main reason people get drawn into this book).

Second, mathematics is beautiful.

Third, mathematics is useful.

There are also differences in usefulness.

Mathematical ideas or methods may be useful in other fields of mathematics, they may be useful to theoretical scientists, they may be useful in the laboratory, they may be useful in the world of industry and commerce, and they may be useful in the everyday lives of ordinary citizens.

--- p.119, from “Empires on the Moon”

One of the charms of mathematics is that problems made up of very simple elements, easy to explain, and involving numerous proofs can puzzle the world's greatest geniuses for hundreds of years.

Fermat's Last Theorem, Kepler's problem, and the four-color conjecture are examples.

As I will briefly explain later, all of these problems have been solved over the past few decades.

One of the joys of amateur mathematics is finding solutions to famous unsolved problems, even if the chances of success are slim.

--- p.183, from “The Tangled Rails of the Brick Factory”

Why do phone cords always get tangled? The cord I'm talking about is a long, coiled cord that can be pulled to lengthen it.

The handset of the old-fashioned telephone, which was sometimes hung on the wall, was connected to the main unit with a cord like that.

When you first buy a phone and hang it on the wall, the cord hangs down nicely and neatly.

But after a few weeks, tangles start to form.

--- p.219, from “Why are telephone cords always tangled?”

The tradition of explaining mathematics through games and puzzles dates back at least to ancient Babylonia.

Babylonian clay tablets contain riddles that could be considered modern-day 'applied problems' in arithmetic.

As all sorts of new branches of mathematics developed rapidly, entirely new games emerged, the rules of which cannot be explained without invoking concepts from topology and set theory, concepts completely unknown to the Babylonians.

--- p.259, from “Taking Triangulation”

Since Christmas always falls on December 25th, there is no difficulty in calculating the date of Christmas.

But Easter is a completely different story.

Easter can fall on any date between March 22nd and April 25th.

This means that the possible dates are spread out over a five-week period.

The early Christian church devised its own methods to calculate the date of Easter.

Some people are very difficult to please.

For the past 50 years, mathematicians have wrestled with the problem of fair distribution.

There is now a comprehensive and surprisingly profound theory on the subject, which is usually discussed with cakes rather than fish.

--- pp.17~18, from “Your Half is Bigger than My Half”

People often talk about the 'law of averages'.

The basis is the intuition that if you flip a coin repeatedly, you should eventually get a consistent result.

Some even believe that in such cases, the chances of a comeback are higher.

We often think, “This time, it’s more likely to be the latter.”

Others assert that coins have no memory.

--- p.29, from “Are the odds of a coin toss fair?”

There are at least three common ways to tie your shoelaces.

See Figure 5.

These are the American zigzag tying, the European straight tying, and the quick tying, which is mainly used in shoe stores.

From a buyer's perspective, shoelace tying methods are differentiated by how attractive they are and how cumbersome they are.

But the more important question from the producer's point of view is which method has the shortest string (which method is the cheapest).

--- p.48, from “Tying Your Shoes with the Shortest Laces”

Mathematics interests people for at least three reasons.

First, math is fun (which is the main reason people get drawn into this book).

Second, mathematics is beautiful.

Third, mathematics is useful.

There are also differences in usefulness.

Mathematical ideas or methods may be useful in other fields of mathematics, they may be useful to theoretical scientists, they may be useful in the laboratory, they may be useful in the world of industry and commerce, and they may be useful in the everyday lives of ordinary citizens.

--- p.119, from “Empires on the Moon”

One of the charms of mathematics is that problems made up of very simple elements, easy to explain, and involving numerous proofs can puzzle the world's greatest geniuses for hundreds of years.

Fermat's Last Theorem, Kepler's problem, and the four-color conjecture are examples.

As I will briefly explain later, all of these problems have been solved over the past few decades.

One of the joys of amateur mathematics is finding solutions to famous unsolved problems, even if the chances of success are slim.

--- p.183, from “The Tangled Rails of the Brick Factory”

Why do phone cords always get tangled? The cord I'm talking about is a long, coiled cord that can be pulled to lengthen it.

The handset of the old-fashioned telephone, which was sometimes hung on the wall, was connected to the main unit with a cord like that.

When you first buy a phone and hang it on the wall, the cord hangs down nicely and neatly.

But after a few weeks, tangles start to form.

--- p.219, from “Why are telephone cords always tangled?”

The tradition of explaining mathematics through games and puzzles dates back at least to ancient Babylonia.

Babylonian clay tablets contain riddles that could be considered modern-day 'applied problems' in arithmetic.

As all sorts of new branches of mathematics developed rapidly, entirely new games emerged, the rules of which cannot be explained without invoking concepts from topology and set theory, concepts completely unknown to the Babylonians.

--- p.259, from “Taking Triangulation”

Since Christmas always falls on December 25th, there is no difficulty in calculating the date of Christmas.

But Easter is a completely different story.

Easter can fall on any date between March 22nd and April 25th.

This means that the possible dates are spread out over a five-week period.

The early Christian church devised its own methods to calculate the date of Easter.

--- p.271, from "Guessing the Easter Date"

Publisher's Review

You will realize how broad the subject of mathematics is, how much richer it is than the mathematics you learned in school.

How diversely it can be applied, and yet how different parts of mathematics can be used.

You will gain a better understanding of how things are tightly connected to form a whole.

Moreover, all of them will be obtained through solving puzzles and playing games.

The important thing is to be flexible in your thinking.

Never underestimate the power of play.

- From 'Entering'

▼ Ian Stewart's beloved extreme math problems intertwined with our daily lives.

For some, mathematics is a subject that brings pure terror, but for others, it is a language for understanding the world and a fun game.

Like the author of this book, Ian Stewart.

Stewart says mathematics is a source of inspiration and joy for him.

Of course, I also know that just as not everyone can understand a birdwatcher's passion for birds, not everyone can enjoy a passion for mathematics.

So, this book is for people who already know the appeal of mathematics and people who actively enjoy mathematics.

Ian Stewart invites readers into a world of 20 challenging math puzzles that will make math fun.

This book provides a glimpse into the ways in which mathematical geniuses view the world and solve problems, covering probability, statistics, geometry, topology, and graph theory.

Through 20 puzzles that have long stimulated the curiosity and inquisitiveness of mathematicians, readers can approach the core of modern mathematics in an easier and more engaging way.

Stewart corrected all the errors he found, based on columns about math games published in Scientific American from 1987 to 2001.

At the end of the text are readers' comments on each chapter. Reading them while comparing them with your own thoughts will make for an even more enjoyable read.

Stewart says the book's goal is to blend abstract ideas with the real world, eliciting a variety of mathematical ideas from math-enthusiast readers.

I hope to not only obtain practical solutions to mathematical problems applied in reality, but also to discover new mathematical possibilities.

Of course, it is very difficult to apply and develop important mathematics in a few pages of text.

However, it is possible to appreciate with enough imagination how mathematical ideas derived from one situation can unexpectedly be applied to another.

▼ Read about algorithms in cake sharing and see minimal surfaces in soap bubbles.

Even sharing a cake becomes difficult if there is a condition attached that 'it must be shared fairly without anyone complaining.'

It is mathematics that teaches us how to fairly divide the cake among several people.

The subject of 'cutting a cake' is a mathematical problem that dates back at least 3,500 years to ancient Babylonia.

Yet, no clear answer has been known to this day.

The solution presented in the book is that one person cuts and another person chooses.

Of course, to borrow James Frazley's commentary mentioned in the feedback, the task of solving the problem of distribution without jealousy has nothing to do with reality or calculation.

Because to humans, the grass always looks greener on the other side.

The best mathematics has a strange universality.

The story of 'Why are phone cords always tangled?' is useful not only for untangling phone cords.

There are many things that are tangled and wound in reality.

Plant tendrils, DNA molecules, and undersea communication cables are also common and easily tangled objects.

Although seemingly different, the mathematical model that allows us to understand these phenomena is simple.

Of course, the model doesn't give you all the answers you want.

However, it is important because it opens the way to mathematical analysis, on the basis of which more complex and detailed models can be developed.

The book also shows that mathematics has serious applications in everyday life, through ideas gleaned by chance, such as winning lottery numbers, the date of a surprise exam, a magic trick that makes cards return to their original positions after being shuffled, how Roman emperors deployed their armies, how to color maps, and the unusual behavior of Asian fireflies.

What Stewart wants to say in the book is that by blending abstract ideas with the real world, we can derive various mathematical ideas.

Of course, you may not understand this book 100%.

But even ordinary readers can get lost in solving puzzles and experience ample intellectual pleasure.

The book is structured independently for each chapter, so it doesn't matter which one you read first.

Of course, you can read the chapters that you feel are easy first.

After reading this book, you will realize how broad the subject of mathematics is, how much richer it is than what you learn in school, and how diverse its applications are.

How diversely it can be applied, and yet how different parts of mathematics can be used.

You will gain a better understanding of how things are tightly connected to form a whole.

Moreover, all of them will be obtained through solving puzzles and playing games.

The important thing is to be flexible in your thinking.

Never underestimate the power of play.

- From 'Entering'

▼ Ian Stewart's beloved extreme math problems intertwined with our daily lives.

For some, mathematics is a subject that brings pure terror, but for others, it is a language for understanding the world and a fun game.

Like the author of this book, Ian Stewart.

Stewart says mathematics is a source of inspiration and joy for him.

Of course, I also know that just as not everyone can understand a birdwatcher's passion for birds, not everyone can enjoy a passion for mathematics.

So, this book is for people who already know the appeal of mathematics and people who actively enjoy mathematics.

Ian Stewart invites readers into a world of 20 challenging math puzzles that will make math fun.

This book provides a glimpse into the ways in which mathematical geniuses view the world and solve problems, covering probability, statistics, geometry, topology, and graph theory.

Through 20 puzzles that have long stimulated the curiosity and inquisitiveness of mathematicians, readers can approach the core of modern mathematics in an easier and more engaging way.

Stewart corrected all the errors he found, based on columns about math games published in Scientific American from 1987 to 2001.

At the end of the text are readers' comments on each chapter. Reading them while comparing them with your own thoughts will make for an even more enjoyable read.

Stewart says the book's goal is to blend abstract ideas with the real world, eliciting a variety of mathematical ideas from math-enthusiast readers.

I hope to not only obtain practical solutions to mathematical problems applied in reality, but also to discover new mathematical possibilities.

Of course, it is very difficult to apply and develop important mathematics in a few pages of text.

However, it is possible to appreciate with enough imagination how mathematical ideas derived from one situation can unexpectedly be applied to another.

▼ Read about algorithms in cake sharing and see minimal surfaces in soap bubbles.

Even sharing a cake becomes difficult if there is a condition attached that 'it must be shared fairly without anyone complaining.'

It is mathematics that teaches us how to fairly divide the cake among several people.

The subject of 'cutting a cake' is a mathematical problem that dates back at least 3,500 years to ancient Babylonia.

Yet, no clear answer has been known to this day.

The solution presented in the book is that one person cuts and another person chooses.

Of course, to borrow James Frazley's commentary mentioned in the feedback, the task of solving the problem of distribution without jealousy has nothing to do with reality or calculation.

Because to humans, the grass always looks greener on the other side.

The best mathematics has a strange universality.

The story of 'Why are phone cords always tangled?' is useful not only for untangling phone cords.

There are many things that are tangled and wound in reality.

Plant tendrils, DNA molecules, and undersea communication cables are also common and easily tangled objects.

Although seemingly different, the mathematical model that allows us to understand these phenomena is simple.

Of course, the model doesn't give you all the answers you want.

However, it is important because it opens the way to mathematical analysis, on the basis of which more complex and detailed models can be developed.

The book also shows that mathematics has serious applications in everyday life, through ideas gleaned by chance, such as winning lottery numbers, the date of a surprise exam, a magic trick that makes cards return to their original positions after being shuffled, how Roman emperors deployed their armies, how to color maps, and the unusual behavior of Asian fireflies.

What Stewart wants to say in the book is that by blending abstract ideas with the real world, we can derive various mathematical ideas.

Of course, you may not understand this book 100%.

But even ordinary readers can get lost in solving puzzles and experience ample intellectual pleasure.

The book is structured independently for each chapter, so it doesn't matter which one you read first.

Of course, you can read the chapters that you feel are easy first.

After reading this book, you will realize how broad the subject of mathematics is, how much richer it is than what you learn in school, and how diverse its applications are.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 25, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 296 pages | 426g | 148*218*16mm

- ISBN13: 9791190467803

- ISBN10: 1190467801

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)