Broca's brain

|

Description

Book Introduction

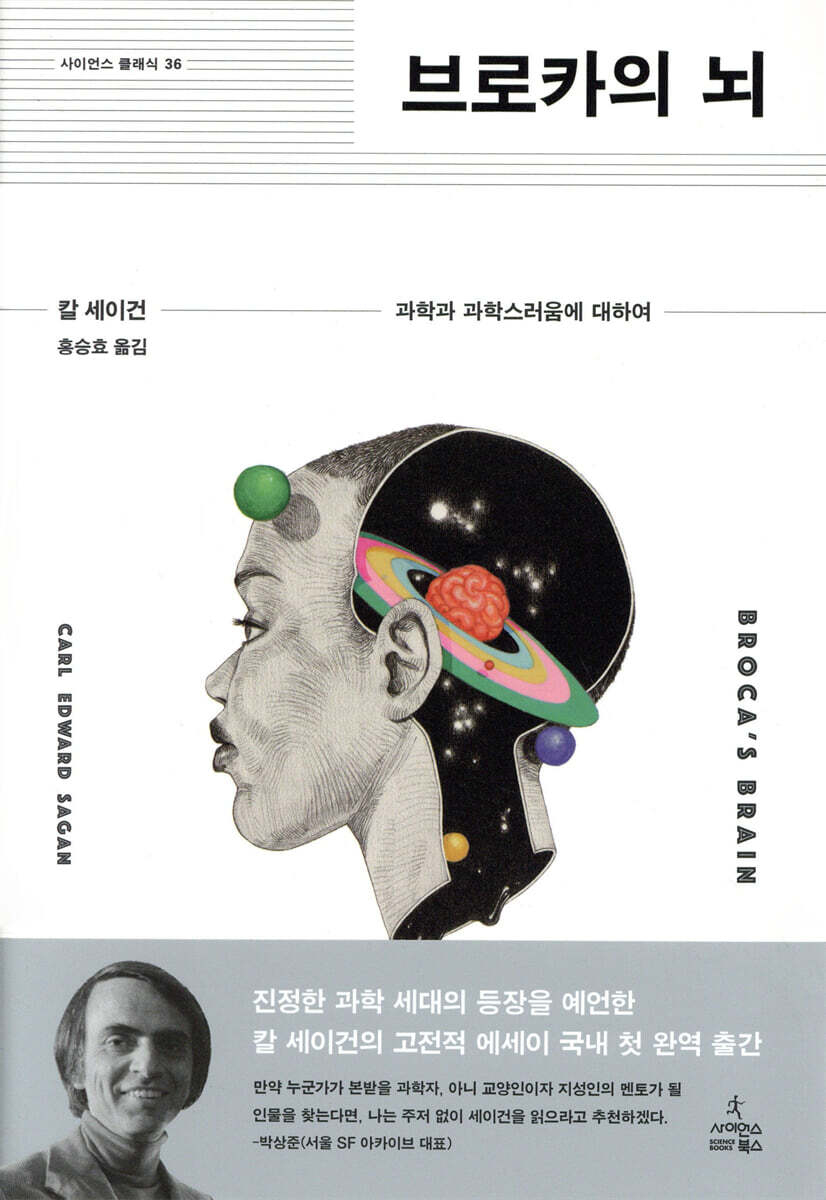

Predicting the emergence of a true scientific generation

Carl Sagan's classic essay, published for the first time in Korea!

If anyone is looking for a mentor, a scientist, or even a cultured and intellectual figure to emulate, I would unhesitatingly recommend reading Sagan.

(_Park Sang-jun (Director of Seoul SF Archive))

2020 marks the 40th anniversary of the publication of Carl Edward Sagan's (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) "COSMOS" series, a seminal event in the popularization of science, in the form of a documentary and book.

The "Cosmos" series, a popular science content series that was both an experiment and a major multimedia project, was broadcast in 60 countries around the world, captivating over 600 million viewers and sparking a science boom.

After Carl Sagan passed away in 1996, his wife Ann Druyan took over the Carl Sagan Studio and Foundation and continued the Cosmos series.

Ann Druyan produced the 13-part documentary Cosmos: A Space Time Odyssey (narrated by Neil deGrasse Tyson) in 2014, which aired in 160 countries worldwide, and in the spring of 2020, Cosmos: Possible Worlds, the official sequel to Sagan's first Cosmos, was published and a third documentary of the same name based on the book aired.

What is the secret of Carl Sagan, who has been loved by people all over the world for 40 years?

A book that will unlock this secret has recently been published by Science Books.

That book is Carl Sagan's Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science.

First published in 1979, the 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein's birth and a year before the launch of the "Cosmos" series, this book collects essays that Carl Sagan published from 1974 to 1979 in various media outlets, from science magazines such as [Scientific American] and [Physics Today] to popular magazines such as [Playboy] and [Atlantic Monthly].

In these writings, Sagan covers a variety of topics.

Analysis of the impact of science on society, sharp critiques of discourses called borderline science, popular science, pseudoscience, and even pseudoscience, a short but impressive biography of the great scientist Einstein, a history of American astronomy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, commentary on the prospects of planetary exploration and artificial intelligence robots, and reflections on religion.

Published between The Dragons of Eden (1977), which won Carl Sagan the Pulitzer Prize and established him as a bestselling author with over a million copies sold, and Cosmos (1980), which established him as a global evangelist for science, this book is full of "missing links" that reveal the process by which a scientist who analyzed the atmospheric environment of Venus and planned planetary exploration plans for NASA became a popular science writer and a scientific thinker with worldwide influence.

Carl Sagan's classic essay, published for the first time in Korea!

If anyone is looking for a mentor, a scientist, or even a cultured and intellectual figure to emulate, I would unhesitatingly recommend reading Sagan.

(_Park Sang-jun (Director of Seoul SF Archive))

2020 marks the 40th anniversary of the publication of Carl Edward Sagan's (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) "COSMOS" series, a seminal event in the popularization of science, in the form of a documentary and book.

The "Cosmos" series, a popular science content series that was both an experiment and a major multimedia project, was broadcast in 60 countries around the world, captivating over 600 million viewers and sparking a science boom.

After Carl Sagan passed away in 1996, his wife Ann Druyan took over the Carl Sagan Studio and Foundation and continued the Cosmos series.

Ann Druyan produced the 13-part documentary Cosmos: A Space Time Odyssey (narrated by Neil deGrasse Tyson) in 2014, which aired in 160 countries worldwide, and in the spring of 2020, Cosmos: Possible Worlds, the official sequel to Sagan's first Cosmos, was published and a third documentary of the same name based on the book aired.

What is the secret of Carl Sagan, who has been loved by people all over the world for 40 years?

A book that will unlock this secret has recently been published by Science Books.

That book is Carl Sagan's Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science.

First published in 1979, the 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein's birth and a year before the launch of the "Cosmos" series, this book collects essays that Carl Sagan published from 1974 to 1979 in various media outlets, from science magazines such as [Scientific American] and [Physics Today] to popular magazines such as [Playboy] and [Atlantic Monthly].

In these writings, Sagan covers a variety of topics.

Analysis of the impact of science on society, sharp critiques of discourses called borderline science, popular science, pseudoscience, and even pseudoscience, a short but impressive biography of the great scientist Einstein, a history of American astronomy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, commentary on the prospects of planetary exploration and artificial intelligence robots, and reflections on religion.

Published between The Dragons of Eden (1977), which won Carl Sagan the Pulitzer Prize and established him as a bestselling author with over a million copies sold, and Cosmos (1980), which established him as a global evangelist for science, this book is full of "missing links" that reveal the process by which a scientist who analyzed the atmospheric environment of Venus and planned planetary exploration plans for NASA became a popular science writer and a scientific thinker with worldwide influence.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Part 1: Science and Humanity

Chapter 1: Broca's Brain 15

Chapter 2: Can We Know the Universe? About a Grain of Salt 31

Chapter 3: As Tempting as Liberation: On Albert Einstein 41

Chapter 4: In Praise of Science and Technology 61

Part 2: The Paradoxists

Chapter 5: Sleepwalkers and Mystery Spreaders 75

Chapter 6: White Dwarfs and Little Green Aliens 109

Chapter 7: Venus and Dr. Velikovsky 133

Chapter 8 Norman Bloom, The Messenger of God 199

Chapter 9: Personal Views on Science Fiction 211

Part 3: Neighbors in the Universe

Chapter 10: The Sun's Family 229

Chapter 11: A Planet Named George 245

Chapter 12 Life in the Solar System 271

Chapter 13: Titan, Saturn's Mysterious Moon 281

Chapter 14: Planetary Climate 291

Chapter 15: Calliope and the Kaaba Temple 303

Chapter 16: The Golden Age of Planetary Exploration 311

Part 4: The Future

Chapter 17: Want to Walk a Little Faster? 329

Chapter 18: Past the Cherry Trees to Mars 337

Chapter 19: Experiments in Space 347

Chapter 20: In Defense of Robots 361

Chapter 21: The Past and Future of American Astronomy 377

Chapter 22: The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence 403

Part 5: The Ultimate Questions

Chapter 23 Sunday Sermon 419

Chapter 24: The World on a Turtle's Back 436

Chapter 25: The Amniotic Cosmos 447

Acknowledgments 466

Appendix 468

Reference 479

Commentary on Broca's Brain: Between Science Fiction and Science (Park Sang-jun, Director of the SF Archive) 482

Search 489

Part 1: Science and Humanity

Chapter 1: Broca's Brain 15

Chapter 2: Can We Know the Universe? About a Grain of Salt 31

Chapter 3: As Tempting as Liberation: On Albert Einstein 41

Chapter 4: In Praise of Science and Technology 61

Part 2: The Paradoxists

Chapter 5: Sleepwalkers and Mystery Spreaders 75

Chapter 6: White Dwarfs and Little Green Aliens 109

Chapter 7: Venus and Dr. Velikovsky 133

Chapter 8 Norman Bloom, The Messenger of God 199

Chapter 9: Personal Views on Science Fiction 211

Part 3: Neighbors in the Universe

Chapter 10: The Sun's Family 229

Chapter 11: A Planet Named George 245

Chapter 12 Life in the Solar System 271

Chapter 13: Titan, Saturn's Mysterious Moon 281

Chapter 14: Planetary Climate 291

Chapter 15: Calliope and the Kaaba Temple 303

Chapter 16: The Golden Age of Planetary Exploration 311

Part 4: The Future

Chapter 17: Want to Walk a Little Faster? 329

Chapter 18: Past the Cherry Trees to Mars 337

Chapter 19: Experiments in Space 347

Chapter 20: In Defense of Robots 361

Chapter 21: The Past and Future of American Astronomy 377

Chapter 22: The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence 403

Part 5: The Ultimate Questions

Chapter 23 Sunday Sermon 419

Chapter 24: The World on a Turtle's Back 436

Chapter 25: The Amniotic Cosmos 447

Acknowledgments 466

Appendix 468

Reference 479

Commentary on Broca's Brain: Between Science Fiction and Science (Park Sang-jun, Director of the SF Archive) 482

Search 489

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

Publication of 『Cosmos』 to commemorate its 40th anniversary

An elegant scientific essay that reveals the missing link in Carl Sagan's thought.

This book was written just before (I think years, decades at most) we found answers in the universe to many of the vexing and wonderful questions about origins and destiny.

Unless we self-destruct, most of us will continue to search for the answer.

If we had been born 50 years ago, we would have wondered about this topic, pondered it deeply, and made many guesses, but we would have been unable to do anything about it.

If I were born 50 years from now, I think the answer would already be out there.

Most of our children will learn the answers to these questions before they even have a chance to ask them.

The most exciting, satisfying, and enjoyable times in life are undoubtedly the times when we emerge from ignorance and become aware of these fundamental subjects.

It is an era that begins with questioning and ends with understanding.

In the four billion years of life on Earth, in the entire four million years of human history, only one generation has had the privilege of living through this unique transition.

It is ourselves.

-In the text

This book, consisting of 25 chapters in 5 parts, can be seen as a dialogue between Carl Sagan and the charlatans who try to package their claims with "scientificity" and the popular science evangelists who try to explain science in an easy-to-understand way, but end up creating misunderstandings instead.

Carl Sagan coined the 19th-century word “paradoxer” to refer to them.

The word means “a person who speaks plausibly about what science understands using unproven, clever explanations and easy-to-understand terms.”

Even during Carl Sagan's lifetime, there were plenty of paradoxical people, and even now, we can see people who are close to being paradoxical all around us, in various media, and on social media.

Professional scientists usually ignore them.

Some even consider it necessary to deprive them of their right to speak without hesitation, even to the point of contempt.

However, Sagan argues that it is worthwhile and necessary to “examine the claims and ideas of paradoxists more closely and compare and contrast their beliefs with those of other belief systems, namely science and religion.”

“This is because the argument and idea also started from serious contemplation about the nature of the world and the role of humans living in it.”

Carl Sagan's sense of balance can be seen in his commentary on the writings of Immanuel Velikovsky (1895–1979), to which he devotes considerable space in this book.

Velikovsky, a Russian medical doctor, published a book titled Worlds in Collision in 1950, which reinterpreted ancient history and argued that the Earth had suffered countless planetary-scale catastrophes, and that the evolution of life on Earth and the rise and fall of human civilization were determined by the impact of these cataclysms.

The book's claim that Venus, ejected from Jupiter, orbited the Earth in an elliptical orbit with a long semi-major axis like a comet and made periodic close encounters with the Earth, causing miraculous events like those described in the Book of Exodus and Isaiah in the Christian Old Testament, offended scientists such as astronomers and geologists, but it gained immense popularity among the public.

American scientists fiercely opposed Velikovsky's claims.

In particular, Harlow Shapley, an authority on American astronomy who served as director of the Harvard Observatory, pressured Macmillan, the publisher of the book, to stop selling it, using a textbook boycott as a weapon. Eventually, in 1952, the publishing rights were transferred to Doubleday.

Despite the opposition of scientists including Shapley, Velikovsky's popularity did not wane, and as subsequent works and similar books that expanded his worldview continued to be published, Velikovsky's claims and ideas exerted a powerful influence on American popular society until 1970.

In this book, Carl Sagan meticulously criticizes Velikovsky's claims point by point, and does not spare his criticism even in the face of fierce opposition from the scientific community, including Shapley.

In the whole Velikovsky affair, the only thing worse than the crude, ignorant, and dogmatic approach taken by Velikovsky and his many supporters is that those who call themselves scientists shamefully tried to ban his book.

The entire scientific community suffered because of this.

-From page 196

By acting in a way that runs counter to the spirit of self-correcting scientific inquiry fueled by free inquiry and vigorous debate, scientists themselves have contributed to the influence of Velikovsky and other pseudoscience.

So how should we respond? Carl Sagan provides a good example of how to respond in this book.

Sagan follows Velikovsky's main arguments closely and meticulously "fact-checks" his claims.

The claim that Venus was formed by a comet ejected from Jupiter is refuted by simple thermodynamic calculations, and the claim that organic matter that fell from the atmosphere of Venus as it passed by Earth became the manna that saved the Jewish people wandering in the wilderness is dismissed by observations that organic matter in the atmosphere of comets was mostly composed of cyanide.

“The Best Solution to Pseudoscience” elegantly demonstrates what science is, without any fuss, contempt, disdain, or dismissal.

It restores the reputation of science that was lost by some scientists who could not control their emotions.

It also elegantly refutes claims like the "Sirius Mystery," which claims that the African Dogon people knew of a white dwarf star for thousands of years, a star that modern astronomy only discovered in the early 20th century, and the "Bible Code," which claims that the history of humanity and the destiny of each person is hidden in the Christian Bible.

Here, we can see the anti-authoritarian and liberal aspects of Carl Sagan's core scientific thought: that "science must be self-correcting," that "science is a method of acquiring knowledge rather than a body of knowledge," and that science "cannot be a reason to suppress new ideas."

Where is the line between science and 'scientificness'?

In an age overflowing with pseudo-discourse disguised as science,

Ask Carl Sagan for directions!

Part 1, “Science and Humanity,” contains four essays that reflect on the relationship between science and human society.

It consists of “Broca’s Brain,” which reflects on whether science judges humans like a Procrustean bed, reinforces prejudice, and serves dominant ideology; “Can We Know the Universe? On a Grain of Salt,” which briefly and concisely summarizes Carl Sagan’s theory of science that science requires “at least the courage to question conventional wisdom” and that humans’ ability to conduct science is due to their connection to the universe in a very broad sense; “Seductive as Liberation,” which is a short biography of Einstein, whom Carl Sagan considered his spiritual mentor, summarizing his life and achievements; and “In Praise of Science and Technology,” which contains the argument for democratizing science that public support is essential for the advancement of science and technology.

In return for freedom of inquiry, scientists have a duty to account for their work.

If science is seen as a closed 'holy profession' too difficult and mysterious for ordinary people to understand, the risk of misuse increases even more.

If science were a subject of general interest and concern, if its enjoyment and social significance were regularly and sufficiently discussed in schools, in the press, and at dinner tables, the possibilities for learning about the real state of the world and improving both the world and humanity would be greatly increased.

This thought, which sometimes haunts me, may still be lingering in Broca's brain, slow-moving with formalin.

-From page 31

I love a universe that contains so much that is unknown, yet at the same time so much that is understandable.

A universe where everything is known would be as static and dull as the heaven of some faint-hearted theologians.

An incomprehensible universe is not fit for thinking beings.

Our ideal universe is very similar to the universe we inhabit.

I really don't think this is a coincidence.

-From page 38

Einstein's life was a rich blend of genius and irony, a passion for the issues of his time, insight into education, and food for thought on the connections between science and politics, a testament to the power of individuals to ultimately change the world.

-From page 43

We are the first species to directly manage our own evolution.

For the first time, we have the means of self-destruction, whether we intend it or not.

I believe we have the means to move humanity through technological adolescence into a mature, long-lasting, and fulfilling stage of development.

However, there is not much time left to decide which path we will take for our children and their future.

-From page 72

Part 2, “The Paradoxists,” specializes in “paradoxists,” including Velikovsky.

From Alexander the Great of Avonuticus, who made a fortune by claiming that snakes were gods, to Uri Geller, who became famous as a psychic, "Sleepwalkers and Mystery Spreaders" deals with those who are on the borderline between fraud and science; "White Dwarfs and Little Green Aliens" refutes Robert Kyle Grenville Temple's (1945-) "The Sirius Mystery", which was first published in the United States in 1976 and became a worldwide bestseller; "Venus and Dr. Velikovsky" refutes Velikovsky's claims through a meticulous analysis spanning over 70 pages (64 pages in the main text, 10 pages in the appendix with mathematical calculations); "Norman Bloom, Messenger of God" is a friendly response to Norman Bloom, who believed himself to be the second coming of Jesus and claimed that the existence of God could be proven by the correspondence between numbers in the Bible and everyday life; "Science Fiction: A Guide to the Golden Age of American Science Fiction" introduces writers who led him to a love of Mars and an interest in astronomy. It consists of “personal opinions.”

You might find it amusing to check out some of Carl Sagan's famous quotes and public praise for science fiction.

I believe that extraordinary things are definitely worth exploring.

But extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

-From page 102

Fierce criticism of new ideas is common in science.

The style of criticism may vary depending on the critic's personality, but overly polite criticism is not helpful to the person proposing the new idea or to the human enterprise of science.

Any substantive objection is permitted and encouraged.

The only exception is to exclude personal attacks on the character or motives of the proposer.

It doesn't matter why the proposer raised the idea or what prompted the opponents to criticize it.

All that matters is whether the idea is true or false, promising or regressive.

-From page 135

We are the first generation to grow up with science fiction novels.

I know many young people who would be interested, but not at all surprised, if we received a message from an alien civilization.

They are already adapted to the future.

It would be no exaggeration to say that if we survive, science fiction will have played a vital role in the maintenance and evolution of human civilization.

-From page 225

Part 3, “Neighbors of the Universe,” consists of articles introducing various aspects of planetary science.

The precise scientific study of the planets in our solar system is an interdisciplinary discipline that Sagan created and that developed alongside his research career.

It consists of “The Solar Family,” which concisely summarizes the achievements of planetary exploration in the late 1970s; “A Planet Named George,” which introduces the history of astronomical nomenclature along with how to name the features of celestial bodies in the solar system; “Life in the Solar System,” which introduces the progress of the search for life in the solar system; “Titan, Saturn’s Enigmatic Moon,” which introduces the research at the time and future vision for Titan, which began to attract the attention of planetary scientists at the time and is now being explored in earnest as Sagan envisioned 40 years later; “Planetary Climates,” which introduces the results of Carl Sagan’s research on the atmospheres and climates of planets in the solar system such as Venus, Earth, and Mars, which is one of his greatest scientific achievements; “Calliope and the Kaaba,” which connects asteroid research with the black stone of the Kaaba in Saudi Arabia; and “The Golden Age of Planetary Exploration,” which provides a glimpse into Carl Sagan’s vision for the future of planetary exploration since the 1980s.

Although 40 years have passed, comparing the translator's note, which notes the progress of current planetary exploration, with Sagan's writings, we can confirm that current planetary exploration in the solar system is progressing largely according to Sagan's vision.

We have suddenly entered an age of exploration and discovery, almost the first since the Renaissance.

I see practical benefits to comparative planetary science for earthbound scientists.

Exploring other worlds would bring a sense of adventure to a society that has largely lost its chance for adventure, and the pursuit of a cosmic perspective would have philosophical implications.

-From page 243

The problem of naming the solar system is not fundamentally a task of exact science.

It has historically been plagued by prejudice and blind patriotism, and has always lacked foresight.

But while it may be a little early to celebrate, it seems astronomers have recently begun taking some major steps toward eliminating bias in their nomenclature and making it more representative of all humanity.

Some people think that this is pointless, or at least arduous, and unrewarding work.

But some of us are convinced that this work is important.

-From page 268

Titan offers an incredible opportunity to study the many types of organic chemicals that may have led to the origin of life on Earth.

Despite its low temperatures, it can no longer be said with certainty that life on Titan is impossible.

The geology of this celestial body's surface may be unique throughout the solar system.

Titan awaits exploration.

-From page 289

When scientists face extremely difficult theoretical problems, they always perform experiments.

But when it comes to studying the climate of the entire planet, experiments are difficult and expensive to conduct, and could potentially create intractable social problems.

Fortunately, nature helps us by placing planets with very different climates and physical variables right next to Earth.

Perhaps the clearest way to test a climatological theory is to see if it can explain the climates of all the neighboring planets: Earth, Mars, and Venus.

Insights gained from studying one planet will undoubtedly help us study others.

-From page 302

It would be fascinating to investigate small fragments of the Kaaba using modern experimental techniques.

We can determine the composition of the stone precisely.

If it is a meteorite, we can determine the age of the cosmic ray exposure.

And it may also be possible to test hypotheses about its origins.

For example, the hypothesis is that the Kaaba stone broke off from an asteroid named 22 Calliope about 5 million years ago, around the time of the birth of mankind, and orbited the sun for geologic time before accidentally landing on the Arabian Peninsula 2,500 years ago.

-From page 310

It is clear that unless we destroy ourselves, humanity will never again be confined to a single world.

Indeed, if space cities are eventually built and human habitation exists on other worlds, humanity's self-destruction will become much more difficult.

We have unknowingly entered a golden age of planetary exploration.

As in similar instances throughout human history, the act of opening one's horizons through exploration is accompanied by an opening of artistic and cultural horizons.

-From page 325

Part 4, “The Future,” covers the future of astronomy, space science, and space exploration technology.

It consists of “Want to Walk a Little Faster?” which deals with the development of communication and transportation, and space probes; “Through the Cherry Trees to Mars” which deals with the life and achievements of Robert Hutchings Goddard (1882-1945), the father of American rocket technology; “Experiments in Space” which deals with the process by which astronomy, which has developed alongside human civilization, has rapidly developed into a precise experimental science in modern times; “In Defense of Robots” which predicts the possibilities of space exploration and changes in daily life that artificial intelligence and robots will bring; “The Past and Future of American Astronomy” which organizes the history of astronomy in the United States in his capacity as chairman of the 75th anniversary committee of the American Astronomical Society; and “The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence” which outlines the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, better known today as the SETI project, and its significance in the history of civilization.

Our survival as a species may depend on the efficient use of food and energy, which may depend on the development of these machines.

The main obstacle is humans.

There seems to be a prejudice against machines that are as good as or better than humans, as well as against machines that perform specific tasks, as being threatening or 'inhuman', and an aversion to creatures made of silicon and germanium (Ge) rather than proteins and nucleic acids.

This feeling comes to you without you even asking for it.

But in many ways, our survival as a species depends on transcending this primitive chauvinism.

To some extent, embracing intelligent machines can be seen as a process of adapting ourselves to a new environment.

-From page 376

Over the past 75 years, astronomy, both world-wide and in the United States, has advanced beyond even the most romantic speculations of late Victorian astronomers.

So what about the next 75 years? - from page 401

Civilization can be broadly divided into two categories.

Those civilizations that make this effort and succeed in making contact and become new members of the loosely connected Galactic Federation community, and those that are unable to make this effort, choose not to make it, or never even imagine trying, and as a result, soon decline and disappear.

-From page 416

In Part 5, "Ultimate Questions," Carl Sagan addresses big questions like religion, the fate of the universe, and death, issues he hasn't addressed in other books or broadcasts.

"Sunday Sermon" seriously deals with the relationship between science and religion in a resonant tone; "The World is on Turtle's Back" compares and explains the expanding cosmology, steady-state cosmology, and oscillatory cosmology based on observational data known up to that time; and "The Amniotic Universe" proposes an interesting religious theory by examining the relationship between near-death experiences and birth experiences (prenatal experiences) and their religious meaning based on the research of psychiatrist Stanislav Grof (1931-), are writings that give the feeling of peeking into the origins of the thoughts deep in Carl Sagan's mind.

Of course, we constantly emphasize unbiased and thorough investigation.

If there were any gods similar to the traditional gods, our curiosity and intelligence would have been given to them.

If someone suppresses our passion to explore the universe and ourselves, we must resist such behavior.

Such oppression would be a denial of God's gift.

-From page 433

In the successful tradition of science, we must let nature reveal the truth to us.

The pace of discovery is accelerating.

The nature of the universe revealed by modern experimental cosmology is very different from what the ancient Greeks assumed about the gods and the universe.

If we can avoid anthropocentrism, if we can fairly and truthfully consider all alternatives, then within the next few decades we may, for the first time, be able to rigorously determine the nature and fate of the universe.

-From page 446

The only alternative I can think of is that all humans, without exception, already share a similar experience to that of these travelers returning from the underworld: the feeling of flying, the escape from darkness into light, the encounter with a heroic figure, bathed in light and brilliance, and seen in a haze.

There is only one common experience that matches this description.

It's birth.

-From page 451

Since God can be attributed to a distant place and time, and to an ultimate cause, we would have to know more about the universe than we currently know to be certain that such a God does not exist.

To me, both the certainty of God's existence and the certainty of God's absence seem like extreme self-confidence on a subject that is full of doubt and uncertainty.

A broad range of moderate positions seems acceptable, and given the enormous emotional energy that must be poured into this topic, a courageous open mind seems an essential tool for reducing our collective ignorance on the subject of the reality of God.

-From page 461

There is a very good chance that we will soon discover other intelligent beings deep in the universe.

Some of them may be less developed than us.

And some, perhaps most, are more advanced than we are.

I wonder if all beings who travel through space are creatures who go through a painful birth process.

Beings more advanced than us will have abilities far beyond our comprehension.

In a sense, they may seem like gods to us.

Humanity, still a novice, needs to grow more.

Perhaps in the distant future, our descendants will look back on the long and elusive journey humanity has taken from our distant, dimly remembered starting point on Earth, and vividly recall with understanding and love the history of individuals and groups, and the romance of science and religion.

-From page 464

Beyond the value of information

Full of the value of insight and attitude

The joy of reading classics

The publication of this book is the first complete translation in Korea.

In 1986, an abridged version was published under the title “Buroka’s Brain” as part of Jihaksa’s “Student Science Series.”

However, this edition was translated by selecting only 14 chapters with young readers in mind, and even then, many parts were omitted.

This time, Science Books Inc. signed an official contract with Carl Sagan's copyright holder and published the book, translating all 25 chapters in their entirety. They also added a translator's note that provides an overview of the progress of planetary exploration since the book's publication, improving readability for readers.

Additionally, the cover was decorated with illustrations by young domestic artist Ji Gwa-ja to increase accessibility for young readers.

As Sangjun Park, director of the Seoul SF Archive, who wrote a commentary on the relationship between Carl Sagan and the SF genre, said, this book, which is “filled with insight and attitude that go beyond the value of information,” is still worth reading even after 40 years.

The title of this book is taken from the French surgeon, anatomist, and anthropologist Pierre Paul Broca (1824–1880).

Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan traveled to Paris on June 1, 1978, to commemorate the first anniversary of their love affair, and visited the Musée d'Anthropologie in Paris, where they encountered Broca's brain, which had been stored deep in its vaults since the summer of 1880.

(This episode is also featured in Ann Druyan's Cosmos: Possible Worlds.) We looked at Broca's brain, which was submerged in a jar of formalin, and examined his brain folds and his language center (Broca's area).

In doing so, I reflected on Broca's life and achievements and reflected on the potential misuse of science, symbolized by the eerie collections of the Museum of Anthropology.

“Holding his brain in my hand,” he muttered, “I wondered if in some sense Broca was still inside him.”

So, what kind of thoughts does Carl Sagan have in his book, Broca's Brain?

An elegant scientific essay that reveals the missing link in Carl Sagan's thought.

This book was written just before (I think years, decades at most) we found answers in the universe to many of the vexing and wonderful questions about origins and destiny.

Unless we self-destruct, most of us will continue to search for the answer.

If we had been born 50 years ago, we would have wondered about this topic, pondered it deeply, and made many guesses, but we would have been unable to do anything about it.

If I were born 50 years from now, I think the answer would already be out there.

Most of our children will learn the answers to these questions before they even have a chance to ask them.

The most exciting, satisfying, and enjoyable times in life are undoubtedly the times when we emerge from ignorance and become aware of these fundamental subjects.

It is an era that begins with questioning and ends with understanding.

In the four billion years of life on Earth, in the entire four million years of human history, only one generation has had the privilege of living through this unique transition.

It is ourselves.

-In the text

This book, consisting of 25 chapters in 5 parts, can be seen as a dialogue between Carl Sagan and the charlatans who try to package their claims with "scientificity" and the popular science evangelists who try to explain science in an easy-to-understand way, but end up creating misunderstandings instead.

Carl Sagan coined the 19th-century word “paradoxer” to refer to them.

The word means “a person who speaks plausibly about what science understands using unproven, clever explanations and easy-to-understand terms.”

Even during Carl Sagan's lifetime, there were plenty of paradoxical people, and even now, we can see people who are close to being paradoxical all around us, in various media, and on social media.

Professional scientists usually ignore them.

Some even consider it necessary to deprive them of their right to speak without hesitation, even to the point of contempt.

However, Sagan argues that it is worthwhile and necessary to “examine the claims and ideas of paradoxists more closely and compare and contrast their beliefs with those of other belief systems, namely science and religion.”

“This is because the argument and idea also started from serious contemplation about the nature of the world and the role of humans living in it.”

Carl Sagan's sense of balance can be seen in his commentary on the writings of Immanuel Velikovsky (1895–1979), to which he devotes considerable space in this book.

Velikovsky, a Russian medical doctor, published a book titled Worlds in Collision in 1950, which reinterpreted ancient history and argued that the Earth had suffered countless planetary-scale catastrophes, and that the evolution of life on Earth and the rise and fall of human civilization were determined by the impact of these cataclysms.

The book's claim that Venus, ejected from Jupiter, orbited the Earth in an elliptical orbit with a long semi-major axis like a comet and made periodic close encounters with the Earth, causing miraculous events like those described in the Book of Exodus and Isaiah in the Christian Old Testament, offended scientists such as astronomers and geologists, but it gained immense popularity among the public.

American scientists fiercely opposed Velikovsky's claims.

In particular, Harlow Shapley, an authority on American astronomy who served as director of the Harvard Observatory, pressured Macmillan, the publisher of the book, to stop selling it, using a textbook boycott as a weapon. Eventually, in 1952, the publishing rights were transferred to Doubleday.

Despite the opposition of scientists including Shapley, Velikovsky's popularity did not wane, and as subsequent works and similar books that expanded his worldview continued to be published, Velikovsky's claims and ideas exerted a powerful influence on American popular society until 1970.

In this book, Carl Sagan meticulously criticizes Velikovsky's claims point by point, and does not spare his criticism even in the face of fierce opposition from the scientific community, including Shapley.

In the whole Velikovsky affair, the only thing worse than the crude, ignorant, and dogmatic approach taken by Velikovsky and his many supporters is that those who call themselves scientists shamefully tried to ban his book.

The entire scientific community suffered because of this.

-From page 196

By acting in a way that runs counter to the spirit of self-correcting scientific inquiry fueled by free inquiry and vigorous debate, scientists themselves have contributed to the influence of Velikovsky and other pseudoscience.

So how should we respond? Carl Sagan provides a good example of how to respond in this book.

Sagan follows Velikovsky's main arguments closely and meticulously "fact-checks" his claims.

The claim that Venus was formed by a comet ejected from Jupiter is refuted by simple thermodynamic calculations, and the claim that organic matter that fell from the atmosphere of Venus as it passed by Earth became the manna that saved the Jewish people wandering in the wilderness is dismissed by observations that organic matter in the atmosphere of comets was mostly composed of cyanide.

“The Best Solution to Pseudoscience” elegantly demonstrates what science is, without any fuss, contempt, disdain, or dismissal.

It restores the reputation of science that was lost by some scientists who could not control their emotions.

It also elegantly refutes claims like the "Sirius Mystery," which claims that the African Dogon people knew of a white dwarf star for thousands of years, a star that modern astronomy only discovered in the early 20th century, and the "Bible Code," which claims that the history of humanity and the destiny of each person is hidden in the Christian Bible.

Here, we can see the anti-authoritarian and liberal aspects of Carl Sagan's core scientific thought: that "science must be self-correcting," that "science is a method of acquiring knowledge rather than a body of knowledge," and that science "cannot be a reason to suppress new ideas."

Where is the line between science and 'scientificness'?

In an age overflowing with pseudo-discourse disguised as science,

Ask Carl Sagan for directions!

Part 1, “Science and Humanity,” contains four essays that reflect on the relationship between science and human society.

It consists of “Broca’s Brain,” which reflects on whether science judges humans like a Procrustean bed, reinforces prejudice, and serves dominant ideology; “Can We Know the Universe? On a Grain of Salt,” which briefly and concisely summarizes Carl Sagan’s theory of science that science requires “at least the courage to question conventional wisdom” and that humans’ ability to conduct science is due to their connection to the universe in a very broad sense; “Seductive as Liberation,” which is a short biography of Einstein, whom Carl Sagan considered his spiritual mentor, summarizing his life and achievements; and “In Praise of Science and Technology,” which contains the argument for democratizing science that public support is essential for the advancement of science and technology.

In return for freedom of inquiry, scientists have a duty to account for their work.

If science is seen as a closed 'holy profession' too difficult and mysterious for ordinary people to understand, the risk of misuse increases even more.

If science were a subject of general interest and concern, if its enjoyment and social significance were regularly and sufficiently discussed in schools, in the press, and at dinner tables, the possibilities for learning about the real state of the world and improving both the world and humanity would be greatly increased.

This thought, which sometimes haunts me, may still be lingering in Broca's brain, slow-moving with formalin.

-From page 31

I love a universe that contains so much that is unknown, yet at the same time so much that is understandable.

A universe where everything is known would be as static and dull as the heaven of some faint-hearted theologians.

An incomprehensible universe is not fit for thinking beings.

Our ideal universe is very similar to the universe we inhabit.

I really don't think this is a coincidence.

-From page 38

Einstein's life was a rich blend of genius and irony, a passion for the issues of his time, insight into education, and food for thought on the connections between science and politics, a testament to the power of individuals to ultimately change the world.

-From page 43

We are the first species to directly manage our own evolution.

For the first time, we have the means of self-destruction, whether we intend it or not.

I believe we have the means to move humanity through technological adolescence into a mature, long-lasting, and fulfilling stage of development.

However, there is not much time left to decide which path we will take for our children and their future.

-From page 72

Part 2, “The Paradoxists,” specializes in “paradoxists,” including Velikovsky.

From Alexander the Great of Avonuticus, who made a fortune by claiming that snakes were gods, to Uri Geller, who became famous as a psychic, "Sleepwalkers and Mystery Spreaders" deals with those who are on the borderline between fraud and science; "White Dwarfs and Little Green Aliens" refutes Robert Kyle Grenville Temple's (1945-) "The Sirius Mystery", which was first published in the United States in 1976 and became a worldwide bestseller; "Venus and Dr. Velikovsky" refutes Velikovsky's claims through a meticulous analysis spanning over 70 pages (64 pages in the main text, 10 pages in the appendix with mathematical calculations); "Norman Bloom, Messenger of God" is a friendly response to Norman Bloom, who believed himself to be the second coming of Jesus and claimed that the existence of God could be proven by the correspondence between numbers in the Bible and everyday life; "Science Fiction: A Guide to the Golden Age of American Science Fiction" introduces writers who led him to a love of Mars and an interest in astronomy. It consists of “personal opinions.”

You might find it amusing to check out some of Carl Sagan's famous quotes and public praise for science fiction.

I believe that extraordinary things are definitely worth exploring.

But extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

-From page 102

Fierce criticism of new ideas is common in science.

The style of criticism may vary depending on the critic's personality, but overly polite criticism is not helpful to the person proposing the new idea or to the human enterprise of science.

Any substantive objection is permitted and encouraged.

The only exception is to exclude personal attacks on the character or motives of the proposer.

It doesn't matter why the proposer raised the idea or what prompted the opponents to criticize it.

All that matters is whether the idea is true or false, promising or regressive.

-From page 135

We are the first generation to grow up with science fiction novels.

I know many young people who would be interested, but not at all surprised, if we received a message from an alien civilization.

They are already adapted to the future.

It would be no exaggeration to say that if we survive, science fiction will have played a vital role in the maintenance and evolution of human civilization.

-From page 225

Part 3, “Neighbors of the Universe,” consists of articles introducing various aspects of planetary science.

The precise scientific study of the planets in our solar system is an interdisciplinary discipline that Sagan created and that developed alongside his research career.

It consists of “The Solar Family,” which concisely summarizes the achievements of planetary exploration in the late 1970s; “A Planet Named George,” which introduces the history of astronomical nomenclature along with how to name the features of celestial bodies in the solar system; “Life in the Solar System,” which introduces the progress of the search for life in the solar system; “Titan, Saturn’s Enigmatic Moon,” which introduces the research at the time and future vision for Titan, which began to attract the attention of planetary scientists at the time and is now being explored in earnest as Sagan envisioned 40 years later; “Planetary Climates,” which introduces the results of Carl Sagan’s research on the atmospheres and climates of planets in the solar system such as Venus, Earth, and Mars, which is one of his greatest scientific achievements; “Calliope and the Kaaba,” which connects asteroid research with the black stone of the Kaaba in Saudi Arabia; and “The Golden Age of Planetary Exploration,” which provides a glimpse into Carl Sagan’s vision for the future of planetary exploration since the 1980s.

Although 40 years have passed, comparing the translator's note, which notes the progress of current planetary exploration, with Sagan's writings, we can confirm that current planetary exploration in the solar system is progressing largely according to Sagan's vision.

We have suddenly entered an age of exploration and discovery, almost the first since the Renaissance.

I see practical benefits to comparative planetary science for earthbound scientists.

Exploring other worlds would bring a sense of adventure to a society that has largely lost its chance for adventure, and the pursuit of a cosmic perspective would have philosophical implications.

-From page 243

The problem of naming the solar system is not fundamentally a task of exact science.

It has historically been plagued by prejudice and blind patriotism, and has always lacked foresight.

But while it may be a little early to celebrate, it seems astronomers have recently begun taking some major steps toward eliminating bias in their nomenclature and making it more representative of all humanity.

Some people think that this is pointless, or at least arduous, and unrewarding work.

But some of us are convinced that this work is important.

-From page 268

Titan offers an incredible opportunity to study the many types of organic chemicals that may have led to the origin of life on Earth.

Despite its low temperatures, it can no longer be said with certainty that life on Titan is impossible.

The geology of this celestial body's surface may be unique throughout the solar system.

Titan awaits exploration.

-From page 289

When scientists face extremely difficult theoretical problems, they always perform experiments.

But when it comes to studying the climate of the entire planet, experiments are difficult and expensive to conduct, and could potentially create intractable social problems.

Fortunately, nature helps us by placing planets with very different climates and physical variables right next to Earth.

Perhaps the clearest way to test a climatological theory is to see if it can explain the climates of all the neighboring planets: Earth, Mars, and Venus.

Insights gained from studying one planet will undoubtedly help us study others.

-From page 302

It would be fascinating to investigate small fragments of the Kaaba using modern experimental techniques.

We can determine the composition of the stone precisely.

If it is a meteorite, we can determine the age of the cosmic ray exposure.

And it may also be possible to test hypotheses about its origins.

For example, the hypothesis is that the Kaaba stone broke off from an asteroid named 22 Calliope about 5 million years ago, around the time of the birth of mankind, and orbited the sun for geologic time before accidentally landing on the Arabian Peninsula 2,500 years ago.

-From page 310

It is clear that unless we destroy ourselves, humanity will never again be confined to a single world.

Indeed, if space cities are eventually built and human habitation exists on other worlds, humanity's self-destruction will become much more difficult.

We have unknowingly entered a golden age of planetary exploration.

As in similar instances throughout human history, the act of opening one's horizons through exploration is accompanied by an opening of artistic and cultural horizons.

-From page 325

Part 4, “The Future,” covers the future of astronomy, space science, and space exploration technology.

It consists of “Want to Walk a Little Faster?” which deals with the development of communication and transportation, and space probes; “Through the Cherry Trees to Mars” which deals with the life and achievements of Robert Hutchings Goddard (1882-1945), the father of American rocket technology; “Experiments in Space” which deals with the process by which astronomy, which has developed alongside human civilization, has rapidly developed into a precise experimental science in modern times; “In Defense of Robots” which predicts the possibilities of space exploration and changes in daily life that artificial intelligence and robots will bring; “The Past and Future of American Astronomy” which organizes the history of astronomy in the United States in his capacity as chairman of the 75th anniversary committee of the American Astronomical Society; and “The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence” which outlines the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, better known today as the SETI project, and its significance in the history of civilization.

Our survival as a species may depend on the efficient use of food and energy, which may depend on the development of these machines.

The main obstacle is humans.

There seems to be a prejudice against machines that are as good as or better than humans, as well as against machines that perform specific tasks, as being threatening or 'inhuman', and an aversion to creatures made of silicon and germanium (Ge) rather than proteins and nucleic acids.

This feeling comes to you without you even asking for it.

But in many ways, our survival as a species depends on transcending this primitive chauvinism.

To some extent, embracing intelligent machines can be seen as a process of adapting ourselves to a new environment.

-From page 376

Over the past 75 years, astronomy, both world-wide and in the United States, has advanced beyond even the most romantic speculations of late Victorian astronomers.

So what about the next 75 years? - from page 401

Civilization can be broadly divided into two categories.

Those civilizations that make this effort and succeed in making contact and become new members of the loosely connected Galactic Federation community, and those that are unable to make this effort, choose not to make it, or never even imagine trying, and as a result, soon decline and disappear.

-From page 416

In Part 5, "Ultimate Questions," Carl Sagan addresses big questions like religion, the fate of the universe, and death, issues he hasn't addressed in other books or broadcasts.

"Sunday Sermon" seriously deals with the relationship between science and religion in a resonant tone; "The World is on Turtle's Back" compares and explains the expanding cosmology, steady-state cosmology, and oscillatory cosmology based on observational data known up to that time; and "The Amniotic Universe" proposes an interesting religious theory by examining the relationship between near-death experiences and birth experiences (prenatal experiences) and their religious meaning based on the research of psychiatrist Stanislav Grof (1931-), are writings that give the feeling of peeking into the origins of the thoughts deep in Carl Sagan's mind.

Of course, we constantly emphasize unbiased and thorough investigation.

If there were any gods similar to the traditional gods, our curiosity and intelligence would have been given to them.

If someone suppresses our passion to explore the universe and ourselves, we must resist such behavior.

Such oppression would be a denial of God's gift.

-From page 433

In the successful tradition of science, we must let nature reveal the truth to us.

The pace of discovery is accelerating.

The nature of the universe revealed by modern experimental cosmology is very different from what the ancient Greeks assumed about the gods and the universe.

If we can avoid anthropocentrism, if we can fairly and truthfully consider all alternatives, then within the next few decades we may, for the first time, be able to rigorously determine the nature and fate of the universe.

-From page 446

The only alternative I can think of is that all humans, without exception, already share a similar experience to that of these travelers returning from the underworld: the feeling of flying, the escape from darkness into light, the encounter with a heroic figure, bathed in light and brilliance, and seen in a haze.

There is only one common experience that matches this description.

It's birth.

-From page 451

Since God can be attributed to a distant place and time, and to an ultimate cause, we would have to know more about the universe than we currently know to be certain that such a God does not exist.

To me, both the certainty of God's existence and the certainty of God's absence seem like extreme self-confidence on a subject that is full of doubt and uncertainty.

A broad range of moderate positions seems acceptable, and given the enormous emotional energy that must be poured into this topic, a courageous open mind seems an essential tool for reducing our collective ignorance on the subject of the reality of God.

-From page 461

There is a very good chance that we will soon discover other intelligent beings deep in the universe.

Some of them may be less developed than us.

And some, perhaps most, are more advanced than we are.

I wonder if all beings who travel through space are creatures who go through a painful birth process.

Beings more advanced than us will have abilities far beyond our comprehension.

In a sense, they may seem like gods to us.

Humanity, still a novice, needs to grow more.

Perhaps in the distant future, our descendants will look back on the long and elusive journey humanity has taken from our distant, dimly remembered starting point on Earth, and vividly recall with understanding and love the history of individuals and groups, and the romance of science and religion.

-From page 464

Beyond the value of information

Full of the value of insight and attitude

The joy of reading classics

The publication of this book is the first complete translation in Korea.

In 1986, an abridged version was published under the title “Buroka’s Brain” as part of Jihaksa’s “Student Science Series.”

However, this edition was translated by selecting only 14 chapters with young readers in mind, and even then, many parts were omitted.

This time, Science Books Inc. signed an official contract with Carl Sagan's copyright holder and published the book, translating all 25 chapters in their entirety. They also added a translator's note that provides an overview of the progress of planetary exploration since the book's publication, improving readability for readers.

Additionally, the cover was decorated with illustrations by young domestic artist Ji Gwa-ja to increase accessibility for young readers.

As Sangjun Park, director of the Seoul SF Archive, who wrote a commentary on the relationship between Carl Sagan and the SF genre, said, this book, which is “filled with insight and attitude that go beyond the value of information,” is still worth reading even after 40 years.

The title of this book is taken from the French surgeon, anatomist, and anthropologist Pierre Paul Broca (1824–1880).

Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan traveled to Paris on June 1, 1978, to commemorate the first anniversary of their love affair, and visited the Musée d'Anthropologie in Paris, where they encountered Broca's brain, which had been stored deep in its vaults since the summer of 1880.

(This episode is also featured in Ann Druyan's Cosmos: Possible Worlds.) We looked at Broca's brain, which was submerged in a jar of formalin, and examined his brain folds and his language center (Broca's area).

In doing so, I reflected on Broca's life and achievements and reflected on the potential misuse of science, symbolized by the eerie collections of the Museum of Anthropology.

“Holding his brain in my hand,” he muttered, “I wondered if in some sense Broca was still inside him.”

So, what kind of thoughts does Carl Sagan have in his book, Broca's Brain?

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 31, 2020

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 496 pages | 848g | 152*224*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791189198398

- ISBN10: 1189198398

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)