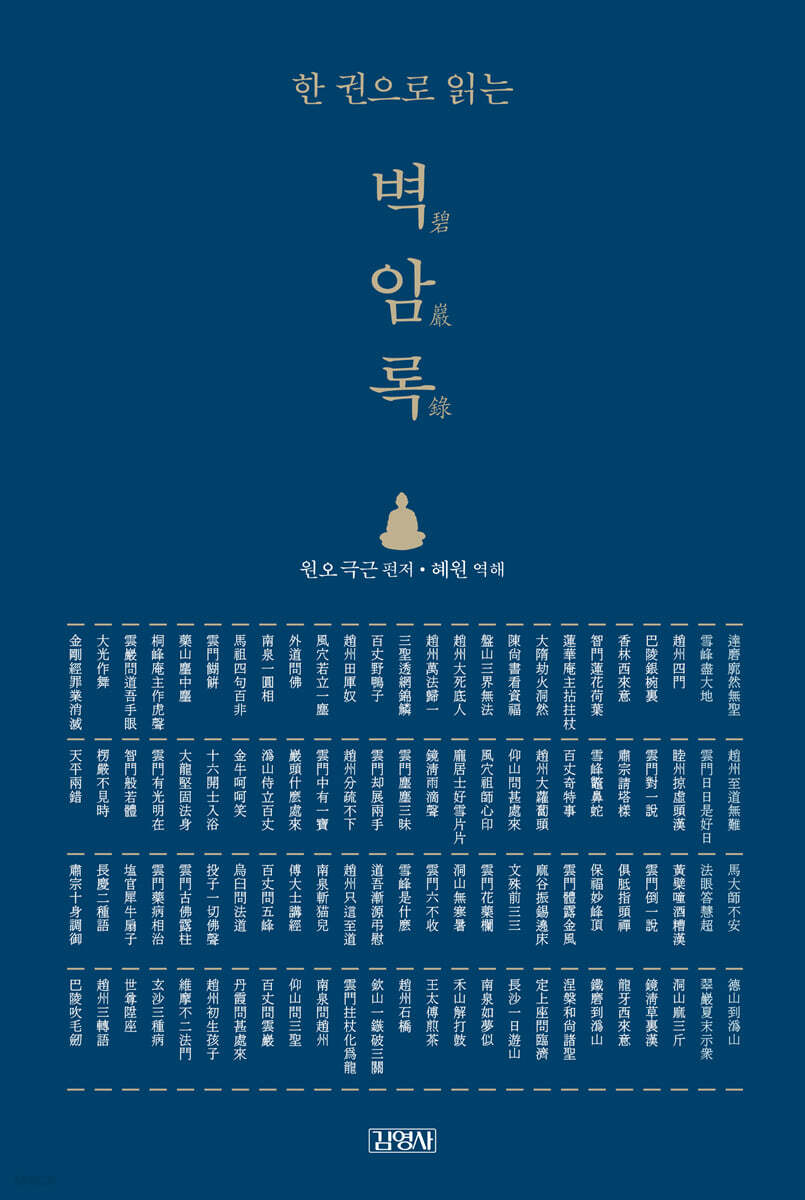

Reading the Wall Rock in One Volume

|

Description

Book Introduction

A feast of character lines that break language by language!

The first book of the Jongmun, challenging the "Byeokamrok"

The "Byeokamrok" has been loved as an excellent guide to Zen meditation for over 900 years since the Song Dynasty in China.

It can be said to be the pinnacle of 'literary Zen', which depicts the realm of truth that transcends language, and the mother of 'conversational Zen', which deals directly with the koan.

However, as the "Byeokamrok" is known as the "first book of the sect," it is difficult to understand and has long reigned as a rugged peak that does not allow access to the general public.

Here, Monk Hyewon, who is familiar with the “Jongyongrok in One Volume,” reveals a new path to reaching the peak of “Byeokamrok.”

《Reading the Record of the Stone Buddha in One Volume》 is a masterpiece that contains the experience and insight of an authentic Zen scholar who has studied and lectured on Zen for over 30 years. It provides detailed and friendly explanations of the exact meaning of the original text and the profound meaning hidden within the text.

This commentary, which is deep and detailed yet not overwhelming in length, will allow both experts and general readers to experience the active strategies of the ancestors.

The first book of the Jongmun, challenging the "Byeokamrok"

The "Byeokamrok" has been loved as an excellent guide to Zen meditation for over 900 years since the Song Dynasty in China.

It can be said to be the pinnacle of 'literary Zen', which depicts the realm of truth that transcends language, and the mother of 'conversational Zen', which deals directly with the koan.

However, as the "Byeokamrok" is known as the "first book of the sect," it is difficult to understand and has long reigned as a rugged peak that does not allow access to the general public.

Here, Monk Hyewon, who is familiar with the “Jongyongrok in One Volume,” reveals a new path to reaching the peak of “Byeokamrok.”

《Reading the Record of the Stone Buddha in One Volume》 is a masterpiece that contains the experience and insight of an authentic Zen scholar who has studied and lectured on Zen for over 30 years. It provides detailed and friendly explanations of the exact meaning of the original text and the profound meaning hidden within the text.

This commentary, which is deep and detailed yet not overwhelming in length, will allow both experts and general readers to experience the active strategies of the ancestors.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Note

Rule 1: Bodhidharma, without any saintliness [達磨廓然無聖] / Rule 2: Joju, without difficulty in leading the way [趙州至道無難] / Rule 3: Majo, without peace [馬大師不安] / Rule 4: Deoksan, going to Wei Mountain [德山到?山] / Rule 5: Seolbong, all the land [雪峰盡大地] / Rule 6: Yunmen, every day is a good day [雲門日日是好日] / Rule 7: Beopyeon, responding to Hyecho [法眼]

[#8: Chwiam, Ha-an-geo Dharma Talk] / [#9: Joju, Four Gates] / [#10: Mokju, A Foolish Bastard]

Rule 11: Hwangbyeok, a guy who eats only wine lees [黃檗?酒糟漢] / Rule 12: Dongsan, three ounces of ma [洞山麻三斤] / Rule 13: Pareung, inside a silver bowl [巴陵銀椀裏] / Rule 14: Yunmun, talking about the opposite of the same thing [雲門對一說] / Rule 15: Yunmun, talking about the opposite of the same thing [雲門倒一說] / Rule 16: Gyeongcheong, a worthless guy [鏡淸草裏漢] / Rule 17: Hyangrim, coming to the west [香林西來意] / Rule 18: Sukjong, asking for a pagoda shape [肅宗請塔樣] / Rule 19: Guji, finger-head meditation [俱?指頭禪] / Rule 20: Dragon's teeth come from the west

Rule 21: Lotus Flower, Lotus Leaf [智門蓮花荷葉] / Rule 22: Seolbong, Byeolbi Temple [雪峰鼈鼻蛇] / Rule 23: Retribution, Myobongjeong [保福妙峰頂] / Rule 24: Iron Horse, Reaching Mt. Wisan [鐵磨到?山] / Rule 25: Yeonhwaamju, Capture the Leader [蓮華庵主拈?杖] / Rule 26: Baekjang, Extraordinary and Wonderful [百丈奇特事] / Rule 27: Cloud Gate, Body and Gold Wind [雲門體露金風] / Rule 28: Nirvana Monks, Many Sages [涅槃和尙諸聖] / Rule 29: Daesu, Fierce Flame [大隋劫火洞然] / Rule 30 Zhaozhou, big radish [趙州大蘿蔔頭]

Rule 31: Magok shakes the stone [麻谷振錫?床] / Rule 32: Jeongsangjwa asks Imje [定上座問臨濟] / Rule 33: Jinsangseo sees Jabok [陳尙書看資福] / Rule 34: Angsan asks where he came from [仰山問甚處來] / Rule 35: Manjusri asks Jeonsamsam [文殊前三三] / Rule 36: Jangsa plays in the mountains one day [長沙一日遊山] / Rule 37: Bansan, the three realms are lawless [盤山三界法less] / Rule 38: Punghyeol, the seal of the ancestors [風穴祖師心印] / Rule 39: Yunmun, the peony fence [Cloud Gate Flower Medicine Column] / Rule 40: Namjeon, Like a Dream [Nanjeon Like a Dream]

Rule 41: Joju, a completely dead man [趙州大死底人] / Rule 42: Pangjusa, a wonderful snowflake [龐居士好雪片片] / Rule 43: Dongshan, a place neither cold nor hot [洞山無寒暑] / Rule 44: Hwasan, beating the drum well [禾山解打鼓] / Rule 45: Joju, all laws return to one [趙州萬法歸一] / Rule 46: Listening to the sound of raindrops [鏡淸雨滴聲] / Rule 47: Yunmen, the six uncollected [雲門六不收] / Rule 48: Wangtaebu, brewing tea [王太傅煎茶] / Rule 49: Samseong, a gold leaf that penetrates the net [Three Holy Roads] / 50th Rule Verse, Jinjin Samadhi [Cloud Gate, Three Stars]

Rule 51: Seolbong, what is this! [What is Seolbong?] / Rule 52 Joju, Stone Bridge [趙州石橋] / Rule 53 Baekjang, Wild Duck [百丈野鴨子] / Rule 54 Yunmun, Spread Both Hands [雲門却展兩手] / Rule 55 Dao-oh, Shopkeeper and Condolences [道吾漸源弔慰] / Rule 56 Qinshan, Shoots Three Passes with One Arrow [欽山一鏃破三關] / Rule 57 Joju, Foolish Bastard [趙州田?奴] / Rule 58 Joju, I Cannot Explain [趙州分疏不下] / Rule 59 Joju, Only This Is the Way [趙州只這至道] / Rule 60 Yunmun, The One Who Advocates Becomes Easy [Cloud Gate? Modern Dragon]

Rule 61: Wind Hole, If a Mote of Dust Stands Up [風穴若立一塵] / Rule 62: Cloud Gate, There is a Treasure in the Middle [雲門中有一寶] / Rule 63: Nanquan Cuts a Cat [南泉斬猫兒] / Rule 64: Nanquan Asks Joju [南泉問趙州] / Rule 65: The Outsider Asks the Buddha [外道問佛] / Rule 66: Amdu, Where Did It Come From [巖頭什?處來] / Rule 67: Master Fu Lectures on the Diamond Sutra [傅大士講經] / Rule 68: Angsan Asks the Three Sages [仰山問三聖] / Rule 69: Namjeon, Ilwonsang [南泉一圓相] / Rule 70: Mount Wei and Baekjang are appointed [?山侍立百丈]

Rule 71: Baekjang asks the Five Peaks [百丈問五峰] / Rule 72: Baekjang asks the Five Peaks [百丈問雲巖] / Rule 73: Majo asks the Four Qurans and a Hundred Nonsense [馬祖四句百非] / Rule 74: Geumwoo laughs loudly [金牛呵呵笑] / Rule 75: Ogu asks the Dharma [烏臼問法道] / Rule 76: Danha asks where he came from [丹霞問甚處來] / Rule 77: Yunmun asks the Hotteok [雲門?餠] / Rule 78: Sixteen Bodhisattvas attain enlightenment in the bathtub [十六開士入浴] / Rule 79: Tujia: All sounds are the sounds of the Buddha [Throwing Zi into All Buddha Voices] / Rule 80: Zhao Zhu, the Newborn Baby [Zhao Zhu, the Newborn Baby]

Rule 81: Yaksan, the king of kings [藥山?中?] / Rule 82: Great Dragon, the firm dharma body [大龍堅固法身] / Rule 83: Yunmen, the old Buddha and the pillar [雲門古佛露柱] / Rule 84: Vima, the non-dual dharma gate [維摩不二法門] / Rule 85: Dongbong, the tiger makes a sound [桐峰庵主作虎聲] / Rule 86: Yunmen, there is light [雲門有光明在] / Rule 87: Yunmen, medicine and disease treat each other [雲門藥病相治] / Rule 88: Hyeonsa, the three diseases [玄沙三種病] / Rule 89: Yunam asks Do-oh about his hands and eyes [The way of thinking about the clouds and the hands and eyes] / The 90th rule, the body of prajna [The body of knowledge and movement]

Rule 91: The rhinoceros fan [?官犀牛扇子] / Rule 92: The World-Honored One ascends the throne [世尊陞座] / Rule 93: The Great Light dances [大光作舞] / Rule 94: The Surangama Sutra, When not seen [楞嚴不見時] / Rule 95: The two types of speech [長慶二種語] / Rule 96: The three types of speech [趙州三轉語] / Rule 97: The Diamond Sutra, The elimination of sins [金剛經罪業消滅] / Rule 98: The two mistakes in the balance [天平兩錯] / Rule 99: King Sukjong, the ten body stipulations [肅宗十身調御] / Rule 100: Paring, the Blowing Sword

Commentary on the "Byeokamrok"

Translator's Note

Appendix 1: Buddhist Dharma Realm Diagram

Appendix 2: Biography of the Prehistoric Beings in the "Byeokamrok"

References

Rule 1: Bodhidharma, without any saintliness [達磨廓然無聖] / Rule 2: Joju, without difficulty in leading the way [趙州至道無難] / Rule 3: Majo, without peace [馬大師不安] / Rule 4: Deoksan, going to Wei Mountain [德山到?山] / Rule 5: Seolbong, all the land [雪峰盡大地] / Rule 6: Yunmen, every day is a good day [雲門日日是好日] / Rule 7: Beopyeon, responding to Hyecho [法眼]

[#8: Chwiam, Ha-an-geo Dharma Talk] / [#9: Joju, Four Gates] / [#10: Mokju, A Foolish Bastard]

Rule 11: Hwangbyeok, a guy who eats only wine lees [黃檗?酒糟漢] / Rule 12: Dongsan, three ounces of ma [洞山麻三斤] / Rule 13: Pareung, inside a silver bowl [巴陵銀椀裏] / Rule 14: Yunmun, talking about the opposite of the same thing [雲門對一說] / Rule 15: Yunmun, talking about the opposite of the same thing [雲門倒一說] / Rule 16: Gyeongcheong, a worthless guy [鏡淸草裏漢] / Rule 17: Hyangrim, coming to the west [香林西來意] / Rule 18: Sukjong, asking for a pagoda shape [肅宗請塔樣] / Rule 19: Guji, finger-head meditation [俱?指頭禪] / Rule 20: Dragon's teeth come from the west

Rule 21: Lotus Flower, Lotus Leaf [智門蓮花荷葉] / Rule 22: Seolbong, Byeolbi Temple [雪峰鼈鼻蛇] / Rule 23: Retribution, Myobongjeong [保福妙峰頂] / Rule 24: Iron Horse, Reaching Mt. Wisan [鐵磨到?山] / Rule 25: Yeonhwaamju, Capture the Leader [蓮華庵主拈?杖] / Rule 26: Baekjang, Extraordinary and Wonderful [百丈奇特事] / Rule 27: Cloud Gate, Body and Gold Wind [雲門體露金風] / Rule 28: Nirvana Monks, Many Sages [涅槃和尙諸聖] / Rule 29: Daesu, Fierce Flame [大隋劫火洞然] / Rule 30 Zhaozhou, big radish [趙州大蘿蔔頭]

Rule 31: Magok shakes the stone [麻谷振錫?床] / Rule 32: Jeongsangjwa asks Imje [定上座問臨濟] / Rule 33: Jinsangseo sees Jabok [陳尙書看資福] / Rule 34: Angsan asks where he came from [仰山問甚處來] / Rule 35: Manjusri asks Jeonsamsam [文殊前三三] / Rule 36: Jangsa plays in the mountains one day [長沙一日遊山] / Rule 37: Bansan, the three realms are lawless [盤山三界法less] / Rule 38: Punghyeol, the seal of the ancestors [風穴祖師心印] / Rule 39: Yunmun, the peony fence [Cloud Gate Flower Medicine Column] / Rule 40: Namjeon, Like a Dream [Nanjeon Like a Dream]

Rule 41: Joju, a completely dead man [趙州大死底人] / Rule 42: Pangjusa, a wonderful snowflake [龐居士好雪片片] / Rule 43: Dongshan, a place neither cold nor hot [洞山無寒暑] / Rule 44: Hwasan, beating the drum well [禾山解打鼓] / Rule 45: Joju, all laws return to one [趙州萬法歸一] / Rule 46: Listening to the sound of raindrops [鏡淸雨滴聲] / Rule 47: Yunmen, the six uncollected [雲門六不收] / Rule 48: Wangtaebu, brewing tea [王太傅煎茶] / Rule 49: Samseong, a gold leaf that penetrates the net [Three Holy Roads] / 50th Rule Verse, Jinjin Samadhi [Cloud Gate, Three Stars]

Rule 51: Seolbong, what is this! [What is Seolbong?] / Rule 52 Joju, Stone Bridge [趙州石橋] / Rule 53 Baekjang, Wild Duck [百丈野鴨子] / Rule 54 Yunmun, Spread Both Hands [雲門却展兩手] / Rule 55 Dao-oh, Shopkeeper and Condolences [道吾漸源弔慰] / Rule 56 Qinshan, Shoots Three Passes with One Arrow [欽山一鏃破三關] / Rule 57 Joju, Foolish Bastard [趙州田?奴] / Rule 58 Joju, I Cannot Explain [趙州分疏不下] / Rule 59 Joju, Only This Is the Way [趙州只這至道] / Rule 60 Yunmun, The One Who Advocates Becomes Easy [Cloud Gate? Modern Dragon]

Rule 61: Wind Hole, If a Mote of Dust Stands Up [風穴若立一塵] / Rule 62: Cloud Gate, There is a Treasure in the Middle [雲門中有一寶] / Rule 63: Nanquan Cuts a Cat [南泉斬猫兒] / Rule 64: Nanquan Asks Joju [南泉問趙州] / Rule 65: The Outsider Asks the Buddha [外道問佛] / Rule 66: Amdu, Where Did It Come From [巖頭什?處來] / Rule 67: Master Fu Lectures on the Diamond Sutra [傅大士講經] / Rule 68: Angsan Asks the Three Sages [仰山問三聖] / Rule 69: Namjeon, Ilwonsang [南泉一圓相] / Rule 70: Mount Wei and Baekjang are appointed [?山侍立百丈]

Rule 71: Baekjang asks the Five Peaks [百丈問五峰] / Rule 72: Baekjang asks the Five Peaks [百丈問雲巖] / Rule 73: Majo asks the Four Qurans and a Hundred Nonsense [馬祖四句百非] / Rule 74: Geumwoo laughs loudly [金牛呵呵笑] / Rule 75: Ogu asks the Dharma [烏臼問法道] / Rule 76: Danha asks where he came from [丹霞問甚處來] / Rule 77: Yunmun asks the Hotteok [雲門?餠] / Rule 78: Sixteen Bodhisattvas attain enlightenment in the bathtub [十六開士入浴] / Rule 79: Tujia: All sounds are the sounds of the Buddha [Throwing Zi into All Buddha Voices] / Rule 80: Zhao Zhu, the Newborn Baby [Zhao Zhu, the Newborn Baby]

Rule 81: Yaksan, the king of kings [藥山?中?] / Rule 82: Great Dragon, the firm dharma body [大龍堅固法身] / Rule 83: Yunmen, the old Buddha and the pillar [雲門古佛露柱] / Rule 84: Vima, the non-dual dharma gate [維摩不二法門] / Rule 85: Dongbong, the tiger makes a sound [桐峰庵主作虎聲] / Rule 86: Yunmen, there is light [雲門有光明在] / Rule 87: Yunmen, medicine and disease treat each other [雲門藥病相治] / Rule 88: Hyeonsa, the three diseases [玄沙三種病] / Rule 89: Yunam asks Do-oh about his hands and eyes [The way of thinking about the clouds and the hands and eyes] / The 90th rule, the body of prajna [The body of knowledge and movement]

Rule 91: The rhinoceros fan [?官犀牛扇子] / Rule 92: The World-Honored One ascends the throne [世尊陞座] / Rule 93: The Great Light dances [大光作舞] / Rule 94: The Surangama Sutra, When not seen [楞嚴不見時] / Rule 95: The two types of speech [長慶二種語] / Rule 96: The three types of speech [趙州三轉語] / Rule 97: The Diamond Sutra, The elimination of sins [金剛經罪業消滅] / Rule 98: The two mistakes in the balance [天平兩錯] / Rule 99: King Sukjong, the ten body stipulations [肅宗十身調御] / Rule 100: Paring, the Blowing Sword

Commentary on the "Byeokamrok"

Translator's Note

Appendix 1: Buddhist Dharma Realm Diagram

Appendix 2: Biography of the Prehistoric Beings in the "Byeokamrok"

References

Into the book

Although Zen originated from 'dhyana' in India, it was the Chinese Zen Buddhism that defined Zen as 'true self-discovery'.

In India, Zen simply means 'mental stability and unity', but in Zen Buddhism, Zen means 'realizing human nature'.

The history of Zen Buddhism is the story of the Zen masters who attained and practiced their true nature, the 'purity' of the Buddha.

Danha's act of burning a wooden Buddha is the culmination of his intense practice with his whole body, and this story later became a koan called 'Danha Burning a Wooden Buddha'.

---p.563

'Galdeung 葛藤' means vines entangled and wrapped around a tree.

Zen is said to be a form of enlightenment that cannot be expressed in words.

But good also attaches great importance to words.

It creates conflict because we have to express in words a world that cannot be expressed in words.

So, in the line, such words are called 'conflict'.

---p.14

There is no meaning behind the words ‘Ma Samgeun’ or ‘Hotteok’.

Deoksan answered the question, “Just this.”

Because it is a world that cannot be expressed in any other way than by saying, ‘just this.’

If you use words like 'true nature' or 'emptiness', you will end up being bound to true nature or emptiness.

The fact that Unmun described the world beyond the Buddha in just one word, ‘Hotteok’, implies that even that word is unrelated.

In other words, it shows us in a single glance that our daily lives are a world beyond the realm of the Buddha through 'Hotteok'.

---p..439

In the old Zen sect, the expression 'salindo (killing sword)·hwalingeom (living sword)' was used to mean that a Zen master can kill or revive the subjectivity of a student.

Here, the word 'murder' does not mean killing a person, but rather completely denying everything.

This 'killing' is an absolute denial that denies even the act of killing, so it does not harm even a single hair.

On the contrary, 'bow' means uprooting the opponent's subjectivity at once, causing them to lose their life, and thereby greatly saving them.

---p.76

'Jeo-ri-ga-ri' means 'here'.

It is a pronoun symbolizing ‘self-nature,’ ‘Buddhism,’ and ‘the state of enlightenment.’

Since it has no original name, it is also called 'here', 'this guy', 'that', or 'the protagonist'.

In other words, the words of the dark spirit mean, “Why didn’t the ancients try to live here, in enlightenment?”

The 'deceased' is 'Buddha, Buddha, ancestor'.

They achieved great enlightenment, attained great nirvana, and reached the summit of a high mountain, but they did not settle down 'here'.

It is like jumping into the four cycles of life (uterus, egg, dampness, and transformation).

If 'here' is the house where we live, then he is not qualified to investigate.

Living like clouds and water is the essence of a Zen practitioner.

---p.154

The Three Realms are dharma-less, so where can we seek the mind? Seeking the mind is impossible.

That is why it is said in the Diamond Sutra, “It is not full of past mind, it is not full of future mind, it is not full of present mind.”

So then, is there nothing in this world?

Is everything vanity?

When I look up at the sky, I see white clouds drifting leisurely, and below I hear the sound of a stream flowing.

Seoldu sang, “I use the white clouds as my roof and the flowing stream as my zither.”

The 'nothingness' and 'emptiness' mentioned in the line do not mean 'emptiness', which is nothing.

Like ‘white clouds’ or ‘streams’, what is as it is is ‘nothingness’, and what is as ‘nothingness’ is the world of truth.

---p.227

Just as a seal is stamped on paper, its imprint is revealed, so too is the imprint of our true mind revealed as a physical object in heaven and earth.

However, if the seal is left as is, the seal will not be revealed, which is a case of 'no seal'.

The former is a positive position that even tiles and small stones emit light, while the latter is a negative position that even gold loses its shine.

The former is a world of discrimination, and the latter is a world of equality.

Here, Pung-hyeol asked the crowd, “If you don’t want to remove the seal or leave a mark, is it right to stamp it or not stamp it?”

In India, Zen simply means 'mental stability and unity', but in Zen Buddhism, Zen means 'realizing human nature'.

The history of Zen Buddhism is the story of the Zen masters who attained and practiced their true nature, the 'purity' of the Buddha.

Danha's act of burning a wooden Buddha is the culmination of his intense practice with his whole body, and this story later became a koan called 'Danha Burning a Wooden Buddha'.

---p.563

'Galdeung 葛藤' means vines entangled and wrapped around a tree.

Zen is said to be a form of enlightenment that cannot be expressed in words.

But good also attaches great importance to words.

It creates conflict because we have to express in words a world that cannot be expressed in words.

So, in the line, such words are called 'conflict'.

---p.14

There is no meaning behind the words ‘Ma Samgeun’ or ‘Hotteok’.

Deoksan answered the question, “Just this.”

Because it is a world that cannot be expressed in any other way than by saying, ‘just this.’

If you use words like 'true nature' or 'emptiness', you will end up being bound to true nature or emptiness.

The fact that Unmun described the world beyond the Buddha in just one word, ‘Hotteok’, implies that even that word is unrelated.

In other words, it shows us in a single glance that our daily lives are a world beyond the realm of the Buddha through 'Hotteok'.

---p..439

In the old Zen sect, the expression 'salindo (killing sword)·hwalingeom (living sword)' was used to mean that a Zen master can kill or revive the subjectivity of a student.

Here, the word 'murder' does not mean killing a person, but rather completely denying everything.

This 'killing' is an absolute denial that denies even the act of killing, so it does not harm even a single hair.

On the contrary, 'bow' means uprooting the opponent's subjectivity at once, causing them to lose their life, and thereby greatly saving them.

---p.76

'Jeo-ri-ga-ri' means 'here'.

It is a pronoun symbolizing ‘self-nature,’ ‘Buddhism,’ and ‘the state of enlightenment.’

Since it has no original name, it is also called 'here', 'this guy', 'that', or 'the protagonist'.

In other words, the words of the dark spirit mean, “Why didn’t the ancients try to live here, in enlightenment?”

The 'deceased' is 'Buddha, Buddha, ancestor'.

They achieved great enlightenment, attained great nirvana, and reached the summit of a high mountain, but they did not settle down 'here'.

It is like jumping into the four cycles of life (uterus, egg, dampness, and transformation).

If 'here' is the house where we live, then he is not qualified to investigate.

Living like clouds and water is the essence of a Zen practitioner.

---p.154

The Three Realms are dharma-less, so where can we seek the mind? Seeking the mind is impossible.

That is why it is said in the Diamond Sutra, “It is not full of past mind, it is not full of future mind, it is not full of present mind.”

So then, is there nothing in this world?

Is everything vanity?

When I look up at the sky, I see white clouds drifting leisurely, and below I hear the sound of a stream flowing.

Seoldu sang, “I use the white clouds as my roof and the flowing stream as my zither.”

The 'nothingness' and 'emptiness' mentioned in the line do not mean 'emptiness', which is nothing.

Like ‘white clouds’ or ‘streams’, what is as it is is ‘nothingness’, and what is as ‘nothingness’ is the world of truth.

---p.227

Just as a seal is stamped on paper, its imprint is revealed, so too is the imprint of our true mind revealed as a physical object in heaven and earth.

However, if the seal is left as is, the seal will not be revealed, which is a case of 'no seal'.

The former is a positive position that even tiles and small stones emit light, while the latter is a negative position that even gold loses its shine.

The former is a world of discrimination, and the latter is a world of equality.

Here, Pung-hyeol asked the crowd, “If you don’t want to remove the seal or leave a mark, is it right to stamp it or not stamp it?”

---p.233

Publisher's Review

A must-read for Zen practitioners,

Seonmun's three major koans, "Byeokamrok"

A world of truth that cannot be expressed in words,

Finding your way through the police station

A koan is a Zen question-and-answer that is a collection of 'conversations of enlightenment' between a teacher and a student, and is intended to serve as a textbook for practice.

Zen originally transcended the limitations of concepts expressed in language and writing, and was a method of directly conveying the mind from a teacher to a student through one-on-one experience.

However, after the Song Dynasty, Gongan Zen, or Munja Zen, which is performed through 'Gongan', which is a written record of the 'scene of enlightenment' of the ancient Zen masters, became popular.

Seoldu's "Songgobaekchik" and Won-o's "Byeokamrok," a lecture note on it, are the best of the literary line.

《Reading the Record of the Stone Buddha in One Volume》 is a commentary on the record of Zen sayings, in which the monk Hyewon provides a detailed explanation of the hundred carefully selected koans by the monk Seoldu, his elegant Zen poetry, and the lectures of the monk Won-o on these, through objective and accurate interpretation of the original text.

The profound meaning of the original text has been revealed in more detail, and unnecessarily complex explanations have been boldly omitted to provide a clear overview in one volume.

What kind of book is "The Record of the Wall"?

- From the Zen of Nothingness to the Zen of Enlightenment

《Byeokamrok》 is a Zen textbook highly praised as the 'best book of the sect', and is a collection of koans compiled by Zen Master Won-o Geuk-geun in the late 12th century Northern Song Dynasty.

In the early Northern Song Dynasty, Master Seoldu Junghyeon selected 100 teachings from the dialogues of major masters and expressed his enlightenment in the form of a poem, "Seoldu Songgo," to which Won-o Geuk-geun added annotations and commentary.

Won-oh studied “Seoldusonggo” while staying at Jinyeowon in his twenties, and from then on, for over 20 years, he never let go of Gong-an and Seoldusong.

It was at the age of 40, when he was serving as the head priest of Sogaksa Temple, that he attempted to recite the Pyeongchang (Gangseol) of “Seoldusonggo.”

《Byeokamrok》 is a book compiled by his disciples by collecting the lectures that Won-o gave three times, adding commentary to 《Seoldusonggo》.

It is said that the two characters 'Byeokam' (碧巖) were taken from a text hanging in a room at Hyeopsan Yeongcheonwon.

《Byeokamrok》 consists of a total of 100 rules, and each rule is structured as follows.

(1) Introductory note: This is a note added by Won-o before the main rule as an introduction. There are also rules that do not have an introductory note.

(2) Main rule: Won-o's commentary (also called Won-o's commentary, lower language) on the old rules selected by Seol-du

Pyeongchang (Won-oh's lecture on the main rules) was attached.

(3) Songgo: It consists of Seoldu’s inspirational poem on the main rule, Won-o’s commentary on it (Won-o’s brief comment inserted into Seoldu’s song), and Won-o’s commentary (Won-o’s lecture on Seoldu’s song).

※ This commentary, “Reading the Record of the Byeogam in One Volume,” omits the original text’s original text’s verses and phrases, and only provides commentary on the poems, main text, and song.

《The Record of the Cliff》 is known to be a very difficult book.

In addition to the difficulty of the Zen question and answer itself, which must demonstrate in words the realm of truth that cannot be expressed in words, the structure is complex and multi-layered, making it difficult to read.

Moreover, this book is a collection of lectures, so there is some overlap in the content and some of the author's intentions have been added.

Despite these formal, substantive, and ideological difficulties, the depth and beauty contained in the “Byeokamrok” have captivated Zen practitioners for over 900 years.

Won-o, the author of “Byeok-am-rok,” emphasized that in order to achieve thorough enlightenment, one must not “interpret” the koan but “learn it through active practice.”

In the "Byeokamrok", when we look at Won-o's Pyeongchang, there are many places where there is a strong demand for Dae-o's experience.

So, rather than using complicated doctrines, Won-oh used vivid words that were as vivid as lightning.

In particular, such expressions are frequently seen in the lower language (short comments between the main text and the song), and traces of efforts to express a world of freedom that is not obsessed with anything are evident.

The basic attitudes that Won-o consistently advocates in his Zen practice can be summarized in three points.

First, ‘affirming one’s true self as it is’, that is, ‘no-thing Zen’, is said to be a delusion.

Second, you must gain the experience of a decisive, profound enlightenment.

Saying 'what is is Buddha' is the next thing.

Third, in order to gain the experience of the Great One, it is said that one must abandon the attitude of rationally interpreting the koan according to its literal meaning and instead study it as a single word that has been separated from meaning and logic, that is, as an active sentence.

The book "Byeokamrok", which contains Won-o's view of practice, clearly shows the ideological transition from the Tang Dynasty's Seon to the Song Dynasty's Seon, that is, the process of changing from "Zen of Nothingness" to "Zen of Enlightenment," and is a valuable book that allows us to examine the process of change in Chinese Seon thought and practice methods.

Background of the Birth of "The Record of the Blue Cliffs"

- Non-standing characters and non-separating characters

In contrast to the religious sects that provided a systematic study of the 84,000 sutras by presenting a teaching explanation for each sect, the Seon sect has been transmitting the 'pattern of the ancestors' through direct and practical experience through questions and answers between the teacher and the disciple.

In other words, the masters and disciples of Seonmun were not bound by the framework of texts or language, such as scriptures or teachings, but freely conveyed their spiritual attainments through various means.

The goal of the practice was to enter directly into the boundary of 'true reality' where words cease, into the 'reality' that cannot be defined by words or concepts.

However, after the Song Dynasty, as Seon Buddhism was incorporated into the social system, the internal systems and practices of Seon Buddhism were also institutionally organized and standardized.

Now, Zen dialogue was no longer a one-on-one, secret conversation between teacher and student.

The famous dialogues of the ancient monks were converted into public texts and printed, and just as religious sects explored the scriptures, the Seon community used the records of the Seon sayings to check and use them as indicators for their own practice.

Now, Zen has shifted from the flow of 'not establishing letters' to 'not leaving letters', and has entered the era of letter Zen (koan Zen).

'Gong-an' originally referred to official documents from government offices, but in Seon Buddhism, gon-an is a question and answer from ancient people that is given to practitioners as a problem to be solved.

Practitioners considered collecting and classifying the questions and answers of their predecessors and studying them as a task to be an important method of practice.

The public security reference method is roughly divided into ‘literal line’ and ‘simplified line’.

Character Zen is an exploration of Zen principles through criticism or reinterpretation of koans.

Seoldu Junghyeon's "Seoldu Songgo" and Wono Geukgeun's "Byeokamrok", which lectured on it, are the best of the literary world.

Ganhwa Seon is a meditation that focuses on the group of doubts about a specific koan, reaches the limit of consciousness, and at that extreme, breaks through the group of doubts and gains the actual experience of dramatic great enlightenment.

Won-o's disciple Dae-hye Jong-go creatively inherited Won-o's ideas and completed Ganhwa Seon.

If the 《Seoldusonggo》 by Seoldu Junghyeon of the Unmunjong became the origin of the literary line of Wono Geukgeun of the Imjejong, then 《Seoldusonggo》 and 《Byeokamrok》 can be said to have become the mother of the Ganhwaseon of the Daehyejonggo.

A Summary of Monk Hyewon's Half-Century Research on Chinese Zen

- Challenge the high peak of Byeokam with one volume

《Reading the Record of the Byeokam in One Volume》 is different from other commentaries on the Record of the Byeokam in this way.

1) Simple structure

The core contents of the original text, such as the poem, main rules, and song, are explained in detail, and the secondary elements, such as the comments and annotations, are boldly omitted.

2) Accurate and objective interpretation of the original text and explanation of terms

Based on the long-term research and insight of a professional Zen scholar, an accurate and objective interpretation was provided through comparison and analysis with a vast amount of authoritative Zen literature in the academic world.

In the commentary section, the original text is explained sentence by sentence, and technical terms are explained in detail without omission.

Especially with regard to public security interpretation, this commentary has eliminated subjective impressions and increased objectivity through in-depth discussions with several doctoral researchers specializing in Zen studies over a period of over three years.

Additionally, unfamiliar technical terms are explained in easy-to-understand terms, and depth is added by including interpretations of various Zen texts.

3) Providing background knowledge covering the entire Seonjong Temple

At the end of the text, the flow of Chinese Zen Buddhism is summarized, and a table of contents and brief biographies of major Zen masters are provided as an appendix, helping beginners of Zen understand the overall context of Zen Buddhism and Zen thought, and learn basic knowledge about the characteristics and core ideas of major Zen masters of each era.

《Reading the Record of the Stone Buddha in One Volume》 is a masterpiece that contains the experience and insight of Monk Hyewon, who studied Chinese Zen for half a century and taught students for over 30 years.

Although it is renowned as the best in Jongmun, it is difficult to climb due to its steep cliffs, and this will be a friendly guide to challenge the magnificent scenery.

Seonmun's three major koans, "Byeokamrok"

A world of truth that cannot be expressed in words,

Finding your way through the police station

A koan is a Zen question-and-answer that is a collection of 'conversations of enlightenment' between a teacher and a student, and is intended to serve as a textbook for practice.

Zen originally transcended the limitations of concepts expressed in language and writing, and was a method of directly conveying the mind from a teacher to a student through one-on-one experience.

However, after the Song Dynasty, Gongan Zen, or Munja Zen, which is performed through 'Gongan', which is a written record of the 'scene of enlightenment' of the ancient Zen masters, became popular.

Seoldu's "Songgobaekchik" and Won-o's "Byeokamrok," a lecture note on it, are the best of the literary line.

《Reading the Record of the Stone Buddha in One Volume》 is a commentary on the record of Zen sayings, in which the monk Hyewon provides a detailed explanation of the hundred carefully selected koans by the monk Seoldu, his elegant Zen poetry, and the lectures of the monk Won-o on these, through objective and accurate interpretation of the original text.

The profound meaning of the original text has been revealed in more detail, and unnecessarily complex explanations have been boldly omitted to provide a clear overview in one volume.

What kind of book is "The Record of the Wall"?

- From the Zen of Nothingness to the Zen of Enlightenment

《Byeokamrok》 is a Zen textbook highly praised as the 'best book of the sect', and is a collection of koans compiled by Zen Master Won-o Geuk-geun in the late 12th century Northern Song Dynasty.

In the early Northern Song Dynasty, Master Seoldu Junghyeon selected 100 teachings from the dialogues of major masters and expressed his enlightenment in the form of a poem, "Seoldu Songgo," to which Won-o Geuk-geun added annotations and commentary.

Won-oh studied “Seoldusonggo” while staying at Jinyeowon in his twenties, and from then on, for over 20 years, he never let go of Gong-an and Seoldusong.

It was at the age of 40, when he was serving as the head priest of Sogaksa Temple, that he attempted to recite the Pyeongchang (Gangseol) of “Seoldusonggo.”

《Byeokamrok》 is a book compiled by his disciples by collecting the lectures that Won-o gave three times, adding commentary to 《Seoldusonggo》.

It is said that the two characters 'Byeokam' (碧巖) were taken from a text hanging in a room at Hyeopsan Yeongcheonwon.

《Byeokamrok》 consists of a total of 100 rules, and each rule is structured as follows.

(1) Introductory note: This is a note added by Won-o before the main rule as an introduction. There are also rules that do not have an introductory note.

(2) Main rule: Won-o's commentary (also called Won-o's commentary, lower language) on the old rules selected by Seol-du

Pyeongchang (Won-oh's lecture on the main rules) was attached.

(3) Songgo: It consists of Seoldu’s inspirational poem on the main rule, Won-o’s commentary on it (Won-o’s brief comment inserted into Seoldu’s song), and Won-o’s commentary (Won-o’s lecture on Seoldu’s song).

※ This commentary, “Reading the Record of the Byeogam in One Volume,” omits the original text’s original text’s verses and phrases, and only provides commentary on the poems, main text, and song.

《The Record of the Cliff》 is known to be a very difficult book.

In addition to the difficulty of the Zen question and answer itself, which must demonstrate in words the realm of truth that cannot be expressed in words, the structure is complex and multi-layered, making it difficult to read.

Moreover, this book is a collection of lectures, so there is some overlap in the content and some of the author's intentions have been added.

Despite these formal, substantive, and ideological difficulties, the depth and beauty contained in the “Byeokamrok” have captivated Zen practitioners for over 900 years.

Won-o, the author of “Byeok-am-rok,” emphasized that in order to achieve thorough enlightenment, one must not “interpret” the koan but “learn it through active practice.”

In the "Byeokamrok", when we look at Won-o's Pyeongchang, there are many places where there is a strong demand for Dae-o's experience.

So, rather than using complicated doctrines, Won-oh used vivid words that were as vivid as lightning.

In particular, such expressions are frequently seen in the lower language (short comments between the main text and the song), and traces of efforts to express a world of freedom that is not obsessed with anything are evident.

The basic attitudes that Won-o consistently advocates in his Zen practice can be summarized in three points.

First, ‘affirming one’s true self as it is’, that is, ‘no-thing Zen’, is said to be a delusion.

Second, you must gain the experience of a decisive, profound enlightenment.

Saying 'what is is Buddha' is the next thing.

Third, in order to gain the experience of the Great One, it is said that one must abandon the attitude of rationally interpreting the koan according to its literal meaning and instead study it as a single word that has been separated from meaning and logic, that is, as an active sentence.

The book "Byeokamrok", which contains Won-o's view of practice, clearly shows the ideological transition from the Tang Dynasty's Seon to the Song Dynasty's Seon, that is, the process of changing from "Zen of Nothingness" to "Zen of Enlightenment," and is a valuable book that allows us to examine the process of change in Chinese Seon thought and practice methods.

Background of the Birth of "The Record of the Blue Cliffs"

- Non-standing characters and non-separating characters

In contrast to the religious sects that provided a systematic study of the 84,000 sutras by presenting a teaching explanation for each sect, the Seon sect has been transmitting the 'pattern of the ancestors' through direct and practical experience through questions and answers between the teacher and the disciple.

In other words, the masters and disciples of Seonmun were not bound by the framework of texts or language, such as scriptures or teachings, but freely conveyed their spiritual attainments through various means.

The goal of the practice was to enter directly into the boundary of 'true reality' where words cease, into the 'reality' that cannot be defined by words or concepts.

However, after the Song Dynasty, as Seon Buddhism was incorporated into the social system, the internal systems and practices of Seon Buddhism were also institutionally organized and standardized.

Now, Zen dialogue was no longer a one-on-one, secret conversation between teacher and student.

The famous dialogues of the ancient monks were converted into public texts and printed, and just as religious sects explored the scriptures, the Seon community used the records of the Seon sayings to check and use them as indicators for their own practice.

Now, Zen has shifted from the flow of 'not establishing letters' to 'not leaving letters', and has entered the era of letter Zen (koan Zen).

'Gong-an' originally referred to official documents from government offices, but in Seon Buddhism, gon-an is a question and answer from ancient people that is given to practitioners as a problem to be solved.

Practitioners considered collecting and classifying the questions and answers of their predecessors and studying them as a task to be an important method of practice.

The public security reference method is roughly divided into ‘literal line’ and ‘simplified line’.

Character Zen is an exploration of Zen principles through criticism or reinterpretation of koans.

Seoldu Junghyeon's "Seoldu Songgo" and Wono Geukgeun's "Byeokamrok", which lectured on it, are the best of the literary world.

Ganhwa Seon is a meditation that focuses on the group of doubts about a specific koan, reaches the limit of consciousness, and at that extreme, breaks through the group of doubts and gains the actual experience of dramatic great enlightenment.

Won-o's disciple Dae-hye Jong-go creatively inherited Won-o's ideas and completed Ganhwa Seon.

If the 《Seoldusonggo》 by Seoldu Junghyeon of the Unmunjong became the origin of the literary line of Wono Geukgeun of the Imjejong, then 《Seoldusonggo》 and 《Byeokamrok》 can be said to have become the mother of the Ganhwaseon of the Daehyejonggo.

A Summary of Monk Hyewon's Half-Century Research on Chinese Zen

- Challenge the high peak of Byeokam with one volume

《Reading the Record of the Byeokam in One Volume》 is different from other commentaries on the Record of the Byeokam in this way.

1) Simple structure

The core contents of the original text, such as the poem, main rules, and song, are explained in detail, and the secondary elements, such as the comments and annotations, are boldly omitted.

2) Accurate and objective interpretation of the original text and explanation of terms

Based on the long-term research and insight of a professional Zen scholar, an accurate and objective interpretation was provided through comparison and analysis with a vast amount of authoritative Zen literature in the academic world.

In the commentary section, the original text is explained sentence by sentence, and technical terms are explained in detail without omission.

Especially with regard to public security interpretation, this commentary has eliminated subjective impressions and increased objectivity through in-depth discussions with several doctoral researchers specializing in Zen studies over a period of over three years.

Additionally, unfamiliar technical terms are explained in easy-to-understand terms, and depth is added by including interpretations of various Zen texts.

3) Providing background knowledge covering the entire Seonjong Temple

At the end of the text, the flow of Chinese Zen Buddhism is summarized, and a table of contents and brief biographies of major Zen masters are provided as an appendix, helping beginners of Zen understand the overall context of Zen Buddhism and Zen thought, and learn basic knowledge about the characteristics and core ideas of major Zen masters of each era.

《Reading the Record of the Stone Buddha in One Volume》 is a masterpiece that contains the experience and insight of Monk Hyewon, who studied Chinese Zen for half a century and taught students for over 30 years.

Although it is renowned as the best in Jongmun, it is difficult to climb due to its steep cliffs, and this will be a friendly guide to challenge the magnificent scenery.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: May 26, 2021

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 616 pages | 970g | 152*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788934989578

- ISBN10: 8934989572

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)