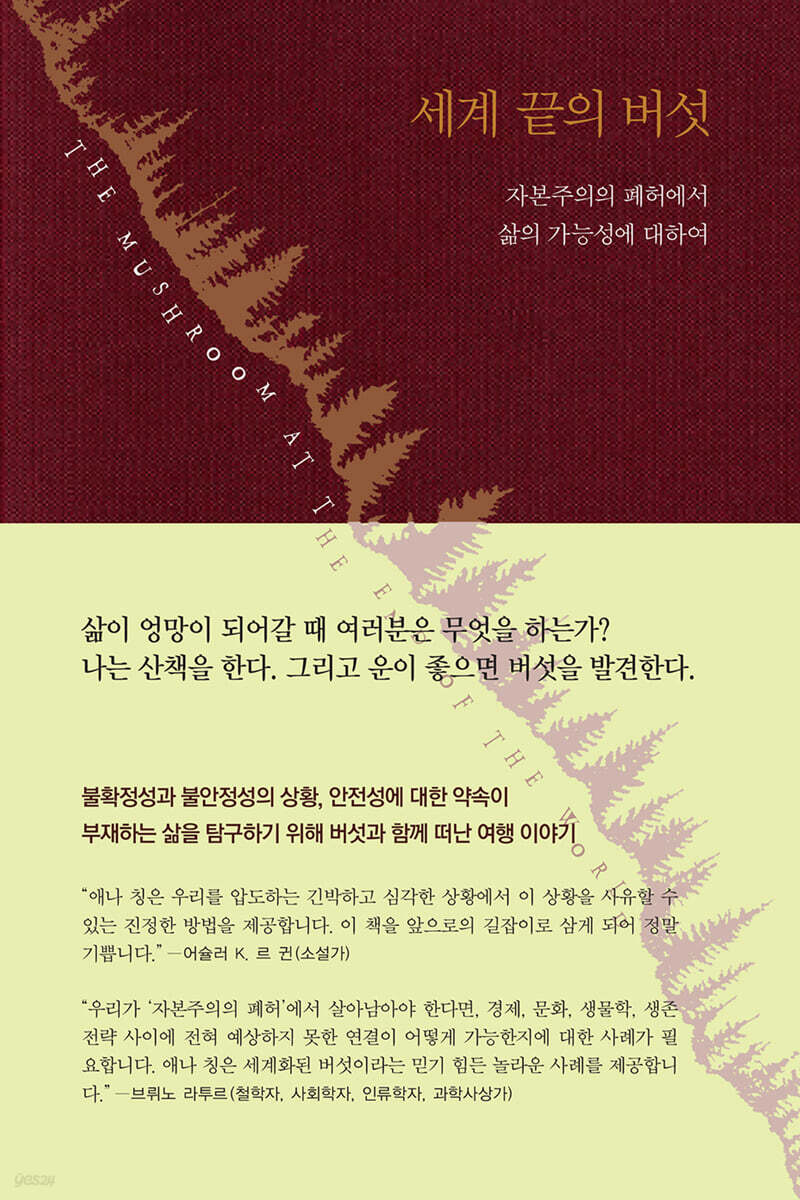

Mushroom at the End of the World

|

Description

Book Introduction

Anna Tsing, a leading thinker in the 21st century, presents her masterpiece, "The Mushroom at the End of the World"! A monumental work of anthropology, introduced for the first time in Korea. "If we are to survive the ruins of capitalism, we need this book." For us who must survive in the midst of ecological and economic collapse, An immortal being, but unable to live alone A precarious survival and a strange new world guided by 'Mushroom' “What do you do when life gets messy? I go for a walk. And if you're lucky, you find mushrooms." A journey with mushrooms to explore a life of uncertainty and instability, a life without the promise of safety. "The Mushroom at the End of the World" explores the unexpected corners of capitalism along one of the strangest commodity chains of our time. On the one hand, we meet Japanese gourmets and capitalist entrepreneurs; on the other, jungle fighters and white war veterans from Laos and Cambodia, goat herders from China's Yunnan province, and nature guides from Finland, all of whom gather pine mushrooms. Meanwhile, in Vancouver, there are Southeast Asian immigrant workers who are called in on a part-time basis to sort matsutake mushrooms. And you'll witness the diverse world of the matsutake trade, from the vibrant, unique auction scenes scattered throughout the Cascade Mountain forests to the auction markets of Tokyo. These companions surrounding the pine mushroom will guide us through the ecology of fungi and the history of the forest. Perhaps we can understand the possibility of coexistence and cohabitation in an age of mass destruction by humans. Tracing the history and present of pine forests, forestry industries, and pine mushroom foragers, a novel unfolds, a strangely intertwined story of pine mushrooms, landscapes, war, freedom, and capitalism. The author explores a wide range of topics, from foraging and forestry to mycology, DNA research, and the music of John Cage. Matsutake mushrooms are the world's most expensive mushrooms, growing only in forests disturbed by humans throughout the Northern Hemisphere, and attempts to cultivate them artificially have failed. “Because pine mushrooms are always in relationships, and therefore exist in specific places.” Pine mushrooms have a special ability to coexist with trees, helping forests grow in harsh environments. What's surprising is that these diverse stories surrounding pine mushrooms offer insights into areas far beyond the simple mushroom story. This book raises important questions about our times through the lens of pine mushrooms. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Things that entangle each other

Prologue: The Scent of Autumn

Part 1: What's Left?

1.

The Art of Awareness | 2.

Pollution as Collaboration | 3.

Problems of scale

Interlude: Smell

After Part 2 Progress: Relief Accumulation

4.

Working the Edges | 5.

Open Ticket in Oregon | 6.

War stories

7.

What Happened to the Nation? Two Types of Asian Americans

8.

Between the dollar and the yen | 9.

From gifts to goods and vice versa

10.

Rescue Rhythm: A Disrupted Business

Interlude: Tracking

Part 3: From Disruption: Unintended Design

11.

Forest Life | 12.

History | 13.

Resurrection | 14.

Unexpected Joy | 15.

ruins

16.

Science as Translation | 17.

flying spores

Interlude: Dancing

While Part 4 is in full swing

18.

Mushroom Activists: Waiting for Fungi to Act | 19.

everyday assets

20.

Against the End: The People I Met Along the Way

A trace made by spores.

The mushroom's challenge to go further

[Release] The Art of Creating a Multi-Type World and Awareness? Nogoun

Search

Prologue: The Scent of Autumn

Part 1: What's Left?

1.

The Art of Awareness | 2.

Pollution as Collaboration | 3.

Problems of scale

Interlude: Smell

After Part 2 Progress: Relief Accumulation

4.

Working the Edges | 5.

Open Ticket in Oregon | 6.

War stories

7.

What Happened to the Nation? Two Types of Asian Americans

8.

Between the dollar and the yen | 9.

From gifts to goods and vice versa

10.

Rescue Rhythm: A Disrupted Business

Interlude: Tracking

Part 3: From Disruption: Unintended Design

11.

Forest Life | 12.

History | 13.

Resurrection | 14.

Unexpected Joy | 15.

ruins

16.

Science as Translation | 17.

flying spores

Interlude: Dancing

While Part 4 is in full swing

18.

Mushroom Activists: Waiting for Fungi to Act | 19.

everyday assets

20.

Against the End: The People I Met Along the Way

A trace made by spores.

The mushroom's challenge to go further

[Release] The Art of Creating a Multi-Type World and Awareness? Nogoun

Search

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

It is said that when Hiroshima was destroyed by the atomic bomb, the first creature to appear in the bombed landscape was the matsutake mushroom.

The acquisition of the atomic bomb came at a time when humanity's dream of dominating nature reached its peak.

And from this point on, the dream began to return to nothing.

The bomb dropped on Hiroshima changed the situation.

Suddenly we realized that humans, whether intentionally or not, could destroy the habitability of the Earth.

This awareness has grown as we learn more about pollution, mass extinction, and climate change.

Half of the current instability concerns the fate of the planet.

What kind of human-induced disruption can we truly live with? Sustainability is being talked about, but what are the chances of us leaving a habitable environment for our multi-species descendants?

--- p.24

The number of things considered “jobs” by 20th-century standards has declined.

Moreover, it seemed that we were all going to die from environmental destruction, whether we had a job or not.

We are faced with the problem of having to survive in the midst of economic and ecological collapse.

Neither the story of progress nor the story of collapse tells us how we can think about cooperative survival.

At this point, let's pay attention to mushroom picking.

Mushroom foraging won't save us, but it might open the doors to our imagination.

--- p.49

Given capitalism's massive destruction of the state and the natural landscape, we might ask why those things that were outside the state and capitalism's project survive today.

To answer this question, we need to look at things on the edges that are difficult to handle.

What brought Mien people and pine mushrooms together in Oregon? This seemingly trivial question could change everything, leading us to see their unpredictable encounter as crucial.

--- p.51

Thanks to the pine mushroom, the host tree can survive even in poor soils lacking fertile humus.

In return, the fungus receives nutrients from the tree.

Because of this unusual symbiosis, human cultivation of pine mushrooms was impossible.

Japanese research institutes have spent millions of yen trying to cultivate matsutake mushrooms, but have not yet succeeded.

Matsutake mushrooms are resistant to the environmental conditions of plantation farms.

--- p.85

Humans have inherited a rich heritage in understanding mushrooms through uncertainty.

The series "Indeterminacy," a series of short performance pieces by American composer John Cage, includes many pieces that celebrate encounters with mushrooms.

Cage saw that finding wild mushrooms required a specific kind of attention.

It is about paying attention to the here and now of the encounter, including all the possibilities and surprises that arise when the encounter occurs.

--- p.95

According to Dr. Ogawa, long before Koreans came to central Japan, they cut down forests to use as fuel for temple construction and forges producing ironware.

They cultivated open, human-disturbed pine forests in Korea where pine mushrooms grew, long before such forests appeared in Japan.

In the 8th century, Koreans came to Japan and cut down the forests.

Pine forests suddenly appeared after such deforestation, and along with them, pine mushrooms.

Koreans smelled the pine mushrooms and thought of their homeland.

That was my first nostalgia and my first love for pine mushrooms.

Dr. Ogawa said that it was out of a longing for Korea that Japan's new aristocracy first praised the now-famous autumn scent.

He added that it is no surprise that Japanese people who have emigrated abroad are obsessed with matsutake mushrooms.

--- p.101-102

Mushroom picking is haunted by the ghost of the city, but it is not a city.

Gathering is not labor either.

It's not even 'work'.

Lao foragers explained that 'work' meant obeying one's superiors and doing the work they were told to do.

On the other hand, picking pine mushrooms is an ‘act of searching.’

It is an act of seeking a large sum of money rather than doing one's own work.

--- p.127

Sorting is an art form! Sorting is like a fire show, a captivating sight, with arms moving rapidly while legs remain still.

White people do it like juggling.

On the other hand, the selection work of Lao women, another excellent buyer, looks like a court Lao dance.

A good picker is someone who knows a lot about mushrooms just by touching them.

…a good buyer knows by feel.

They can also detect the source of mushrooms by smell.

The smell is used to determine the host tree, the area where it was collected, and the presence of other plants such as rhododendron that affect its size and shape.

Everyone enjoys watching the selection process for great buyers.

It is a public performance that shows off one's skills to the fullest.

Sometimes collectors take photographs of the selection process.

Sometimes they even take pictures of the best mushrooms they've found or the best paychecks (especially when they're $100 bills).

Those photos are trophies commemorating mushroom hunting.

--- p.154-155

According to the capitalist logic of commodification, things are separated from the life world they belong to in order to become objects of exchange.

I call this process 'alienation', a term I use to describe a potential attribute of humans as well as non-humans.

A striking observation from the Oregon pine mushroom foraging is that alienation is not involved in the relationship between forager and mushroom.

… even when collected, mushrooms become hunting trophies rather than alienated commodities ready to be converted into capital when sold.

The forager is full of pride and shows off the mushrooms he has picked.

--- p.225

Determining what constitutes a disturbance is always a matter of perspective.

From a human perspective, a disturbance that destroys an anthill is very different from a disturbance that blows up a human city.

From the ant's point of view, this cannot be necessarily seen as such.

Perspectives vary across species.

Rosalind Shaw shows how men and women, urbanites and rural dwellers, rich and poor, conceptualize the floods in Bangladesh differently.

This is because they are affected differently by rising water levels.

The point at which a rise in water levels exceeds tolerable levels and becomes a flood varies from group to group.

A single criterion for assessing disturbance is impossible.

Disruption is a problem that has to do with the way we live.

--- p.286

If you've ever wanted to be inspired by the historical power of plants, I recommend starting with the pine tree.

Pine trees are one of the most active trees on Earth.

If a road is cut through a forest with a bulldozer, there is a good chance that new shoots will grow where the pine trees were cut down.

If people abandoned their farmland, the pine trees would be the first to take over.

When volcanoes erupt, glaciers move, or wind and sea deposit sand, pines will be among the first plants to find a place to put down roots.

--- p.297

Foragers have their own way of recognizing a pine mushroom forest.

That is, they are looking for the lifeline of mushrooms.

Being in the forest in this way can be considered a dance.

They seek lifelines through sensation, movement, and orientation.

This dance is a form of forest knowledge.

However, this is not documented in the report.

And in that sense, all foragers dance, but not all dances are similar.

Each dance takes shape according to a shared history that contains heterogeneous aesthetics and orientations.

To introduce this dance, I go back into the Oregon forest.

--- p.429

We trust our vision too much.

I looked at the ground and thought, 'There's nothing here.'

But as if Marchman had groped around and found something, there was something there.

To get through without progress, we must feel it with our hands.

The acquisition of the atomic bomb came at a time when humanity's dream of dominating nature reached its peak.

And from this point on, the dream began to return to nothing.

The bomb dropped on Hiroshima changed the situation.

Suddenly we realized that humans, whether intentionally or not, could destroy the habitability of the Earth.

This awareness has grown as we learn more about pollution, mass extinction, and climate change.

Half of the current instability concerns the fate of the planet.

What kind of human-induced disruption can we truly live with? Sustainability is being talked about, but what are the chances of us leaving a habitable environment for our multi-species descendants?

--- p.24

The number of things considered “jobs” by 20th-century standards has declined.

Moreover, it seemed that we were all going to die from environmental destruction, whether we had a job or not.

We are faced with the problem of having to survive in the midst of economic and ecological collapse.

Neither the story of progress nor the story of collapse tells us how we can think about cooperative survival.

At this point, let's pay attention to mushroom picking.

Mushroom foraging won't save us, but it might open the doors to our imagination.

--- p.49

Given capitalism's massive destruction of the state and the natural landscape, we might ask why those things that were outside the state and capitalism's project survive today.

To answer this question, we need to look at things on the edges that are difficult to handle.

What brought Mien people and pine mushrooms together in Oregon? This seemingly trivial question could change everything, leading us to see their unpredictable encounter as crucial.

--- p.51

Thanks to the pine mushroom, the host tree can survive even in poor soils lacking fertile humus.

In return, the fungus receives nutrients from the tree.

Because of this unusual symbiosis, human cultivation of pine mushrooms was impossible.

Japanese research institutes have spent millions of yen trying to cultivate matsutake mushrooms, but have not yet succeeded.

Matsutake mushrooms are resistant to the environmental conditions of plantation farms.

--- p.85

Humans have inherited a rich heritage in understanding mushrooms through uncertainty.

The series "Indeterminacy," a series of short performance pieces by American composer John Cage, includes many pieces that celebrate encounters with mushrooms.

Cage saw that finding wild mushrooms required a specific kind of attention.

It is about paying attention to the here and now of the encounter, including all the possibilities and surprises that arise when the encounter occurs.

--- p.95

According to Dr. Ogawa, long before Koreans came to central Japan, they cut down forests to use as fuel for temple construction and forges producing ironware.

They cultivated open, human-disturbed pine forests in Korea where pine mushrooms grew, long before such forests appeared in Japan.

In the 8th century, Koreans came to Japan and cut down the forests.

Pine forests suddenly appeared after such deforestation, and along with them, pine mushrooms.

Koreans smelled the pine mushrooms and thought of their homeland.

That was my first nostalgia and my first love for pine mushrooms.

Dr. Ogawa said that it was out of a longing for Korea that Japan's new aristocracy first praised the now-famous autumn scent.

He added that it is no surprise that Japanese people who have emigrated abroad are obsessed with matsutake mushrooms.

--- p.101-102

Mushroom picking is haunted by the ghost of the city, but it is not a city.

Gathering is not labor either.

It's not even 'work'.

Lao foragers explained that 'work' meant obeying one's superiors and doing the work they were told to do.

On the other hand, picking pine mushrooms is an ‘act of searching.’

It is an act of seeking a large sum of money rather than doing one's own work.

--- p.127

Sorting is an art form! Sorting is like a fire show, a captivating sight, with arms moving rapidly while legs remain still.

White people do it like juggling.

On the other hand, the selection work of Lao women, another excellent buyer, looks like a court Lao dance.

A good picker is someone who knows a lot about mushrooms just by touching them.

…a good buyer knows by feel.

They can also detect the source of mushrooms by smell.

The smell is used to determine the host tree, the area where it was collected, and the presence of other plants such as rhododendron that affect its size and shape.

Everyone enjoys watching the selection process for great buyers.

It is a public performance that shows off one's skills to the fullest.

Sometimes collectors take photographs of the selection process.

Sometimes they even take pictures of the best mushrooms they've found or the best paychecks (especially when they're $100 bills).

Those photos are trophies commemorating mushroom hunting.

--- p.154-155

According to the capitalist logic of commodification, things are separated from the life world they belong to in order to become objects of exchange.

I call this process 'alienation', a term I use to describe a potential attribute of humans as well as non-humans.

A striking observation from the Oregon pine mushroom foraging is that alienation is not involved in the relationship between forager and mushroom.

… even when collected, mushrooms become hunting trophies rather than alienated commodities ready to be converted into capital when sold.

The forager is full of pride and shows off the mushrooms he has picked.

--- p.225

Determining what constitutes a disturbance is always a matter of perspective.

From a human perspective, a disturbance that destroys an anthill is very different from a disturbance that blows up a human city.

From the ant's point of view, this cannot be necessarily seen as such.

Perspectives vary across species.

Rosalind Shaw shows how men and women, urbanites and rural dwellers, rich and poor, conceptualize the floods in Bangladesh differently.

This is because they are affected differently by rising water levels.

The point at which a rise in water levels exceeds tolerable levels and becomes a flood varies from group to group.

A single criterion for assessing disturbance is impossible.

Disruption is a problem that has to do with the way we live.

--- p.286

If you've ever wanted to be inspired by the historical power of plants, I recommend starting with the pine tree.

Pine trees are one of the most active trees on Earth.

If a road is cut through a forest with a bulldozer, there is a good chance that new shoots will grow where the pine trees were cut down.

If people abandoned their farmland, the pine trees would be the first to take over.

When volcanoes erupt, glaciers move, or wind and sea deposit sand, pines will be among the first plants to find a place to put down roots.

--- p.297

Foragers have their own way of recognizing a pine mushroom forest.

That is, they are looking for the lifeline of mushrooms.

Being in the forest in this way can be considered a dance.

They seek lifelines through sensation, movement, and orientation.

This dance is a form of forest knowledge.

However, this is not documented in the report.

And in that sense, all foragers dance, but not all dances are similar.

Each dance takes shape according to a shared history that contains heterogeneous aesthetics and orientations.

To introduce this dance, I go back into the Oregon forest.

--- p.429

We trust our vision too much.

I looked at the ground and thought, 'There's nothing here.'

But as if Marchman had groped around and found something, there was something there.

To get through without progress, we must feel it with our hands.

--- p.488

Publisher's Review

Mushrooms in a bombed landscape

How is cooperative survival possible in a landscape of capitalist destruction and diversity?

It is said that when Hiroshima was destroyed by the atomic bomb, the first creature to appear in the bombed landscape was the matsutake mushroom.

It is said that after the nuclear explosion in Chernobyl, a hard-working and resilient fungus was the first to appear.

Here and there in the desolate forests of the Cascade Mountains, a tributary of the Rocky Mountains, people gather to gather pine mushrooms.

The landscape here vividly illustrates the devastation of the world since the advent of modern capitalism.

What survives in the ruins we humans have created? The author explores that pine mushrooms are experts at dealing with instability.

But the same goes for mushroom pickers.

Political refugees from Southeast Asia, white American veterans, and immigrants from South America tend to live a life of wandering poverty, whether by choice or involuntarily.

These mushroom pickers, part of the precariat suffering from 'mushroom fever', have been unable to find regular employment, do not want it, and prefer the 'freedom' of being alone in the open spaces of nature.

That doesn't mean they are outside of capitalism.

It is integrated into the global economy to some extent through the pine mushroom trade.

They form part of what the author calls the peripheral capitalist space, but are still part of the system.

In unprecedented times of uncertainty,

The message of mushroom ecology and the precarious life of our times, even when we are earning money.

"Mushrooms at the End of the World" explores the cracks in the capitalist world system, where this unstable and uncertain experience of life has become the norm.

The author defines our era as one of instability.

This instability means that even in the United States, the wealthiest country in the world, people no longer have a stable job, the security to educate and raise their children without worrying about their monthly income, or access to medical care when they are sick.

People and things can be discarded at any time as needed.

As people and things become alienated, “the landscape becomes simplified, and the simplified landscape turns into a space abandoned after asset production, that is, a ruin.” (p. 30) Today, the world’s landscape is littered with ruins of this kind.

But is this the end of the story? In traditional narratives, such places should be condemned to death.

Yet, even these places can be vibrant! Abandoned natural landscapes and industrial landscapes sometimes give rise to new, diverse and multicultural lives.

In this place, abandoned and in ruins everywhere, we have no choice but to find life.

"What is survival?

Survival always means fighting against other beings to protect yourself.

“I wouldn’t use survival in that sense.”

If there were conditions for our survival, what would they be? The author asks:

“We are faced with the problem of having to survive in the midst of economic and ecological collapse.

Neither the story of progress nor the story of collapse tells us how we can think about cooperative survival.

At this point, let's pay attention to mushroom picking.

“Mushroom picking won’t save us, but it might open the door to our imagination” (p. 49).

The author says that the first prerequisite for cooperation and survival in unstable times is curiosity.

And the thing is, pine mushrooms can lead us into a world of curiosity.

The idea is that pine mushrooms can provide a kind of symbiotic partnership with humans, taking, stealing, gifting, and selling things in various ways.

When the controlled world we thought was ours fails, the uncontrolled life of mushrooms becomes a gift and a guide.

Perhaps the author sees pine mushrooms as a proxy for survival and wisdom, a tool for human survival in a world devastated by humankind today.

“Only through precarious survival can we see what went wrong.

Insecurity is the state of recognizing that we are vulnerable to other beings.”

The title of Anna Tsing's "Mushrooms at the End of the World" has two meanings.

Mushrooms exist at the very edge of the capitalist world system, where capital accumulation is difficult to achieve.

Of course, being a peripheral area does not mean that it is outside of capitalism.

Pine mushrooms are so secretly hidden deep in the forest that it is difficult to find them.

On the other hand, it could also imply capitalist ruin, the end of the world.

It also implies the meaning of a crisis situation that will ultimately lead to human greed to extract and accumulate as much as possible from the Earth.

Anna Ching uses the tiny organism known as the pine mushroom as a thread to offer surprising insights into how cooperative survival can emerge in a landscape of capitalist destruction and diversity.

“In this mess we have made,

How else can we explain the fact that something is still alive?”

Developed at the complex intersection of humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences

A poetic and surprisingly rich exploration

In fact, summarizing this book in a few lines is nearly impossible.

This is because the 20 or so stories that the author summarizes as “a colorful gathering” unfold like “mushrooms sprouting up after the rain” (page 8).

Still, this book is incredibly fascinating.

One Amazon review calls the book “dangerously fascinating.”

"The Mushroom at the End of the World" is not a dry social science paper.

The book begins by asking, “How else can we explain the fact that something is still alive in this mess we have made of this world?” (p. 8), and its poetic expressions and subtle depictions of social realities can make you feel like you are reading a novel.

There is no neat conclusion, just a series of sharp observations, analyses, and explanations.

It's filled with surprising accounts of the micro and the macro, the individual and the social—the person feeling the forest floor for traces of pine mushrooms, the energy of mushroom auctions, and the unexpected connections in multinational supply chains.

In the author's encounters with countless people and in the passages where he scans the ground in the pine forest and feels a profound connection with the invisible soil organisms, the reader will also sense how non-human beings (plants, animals, soil, etc.) influence our very existence.

And just like the author, readers can also explore the sensations of smelling, touching, searching, and walking along the pace of mushroom picking.

This is the very same 'art of awareness' that artists use to discover the world.

Professor Noh Go-un, who translated it into Korean, presented a topic on ‘ecology’ with Anna Ching at the 2017 Korean Cultural Anthropology Association conference.

The translator has successfully captured the author's unique prose style in Korean, conveying the original text's precise meaning and rich nuances.

It's really original.

…this book transforms the trade and ecology of the extremely rare pine mushroom into a fascinating modern fable about post-industrial survival and environmental regeneration.

―The Guardian

Anna Ching weaves an adventurous tale.

…his passionate account of the intersecting cultures and the resilience of nature offers a fresh perspective on modernity and progress.

―Publisher's Weekly

How is cooperative survival possible in a landscape of capitalist destruction and diversity?

It is said that when Hiroshima was destroyed by the atomic bomb, the first creature to appear in the bombed landscape was the matsutake mushroom.

It is said that after the nuclear explosion in Chernobyl, a hard-working and resilient fungus was the first to appear.

Here and there in the desolate forests of the Cascade Mountains, a tributary of the Rocky Mountains, people gather to gather pine mushrooms.

The landscape here vividly illustrates the devastation of the world since the advent of modern capitalism.

What survives in the ruins we humans have created? The author explores that pine mushrooms are experts at dealing with instability.

But the same goes for mushroom pickers.

Political refugees from Southeast Asia, white American veterans, and immigrants from South America tend to live a life of wandering poverty, whether by choice or involuntarily.

These mushroom pickers, part of the precariat suffering from 'mushroom fever', have been unable to find regular employment, do not want it, and prefer the 'freedom' of being alone in the open spaces of nature.

That doesn't mean they are outside of capitalism.

It is integrated into the global economy to some extent through the pine mushroom trade.

They form part of what the author calls the peripheral capitalist space, but are still part of the system.

In unprecedented times of uncertainty,

The message of mushroom ecology and the precarious life of our times, even when we are earning money.

"Mushrooms at the End of the World" explores the cracks in the capitalist world system, where this unstable and uncertain experience of life has become the norm.

The author defines our era as one of instability.

This instability means that even in the United States, the wealthiest country in the world, people no longer have a stable job, the security to educate and raise their children without worrying about their monthly income, or access to medical care when they are sick.

People and things can be discarded at any time as needed.

As people and things become alienated, “the landscape becomes simplified, and the simplified landscape turns into a space abandoned after asset production, that is, a ruin.” (p. 30) Today, the world’s landscape is littered with ruins of this kind.

But is this the end of the story? In traditional narratives, such places should be condemned to death.

Yet, even these places can be vibrant! Abandoned natural landscapes and industrial landscapes sometimes give rise to new, diverse and multicultural lives.

In this place, abandoned and in ruins everywhere, we have no choice but to find life.

"What is survival?

Survival always means fighting against other beings to protect yourself.

“I wouldn’t use survival in that sense.”

If there were conditions for our survival, what would they be? The author asks:

“We are faced with the problem of having to survive in the midst of economic and ecological collapse.

Neither the story of progress nor the story of collapse tells us how we can think about cooperative survival.

At this point, let's pay attention to mushroom picking.

“Mushroom picking won’t save us, but it might open the door to our imagination” (p. 49).

The author says that the first prerequisite for cooperation and survival in unstable times is curiosity.

And the thing is, pine mushrooms can lead us into a world of curiosity.

The idea is that pine mushrooms can provide a kind of symbiotic partnership with humans, taking, stealing, gifting, and selling things in various ways.

When the controlled world we thought was ours fails, the uncontrolled life of mushrooms becomes a gift and a guide.

Perhaps the author sees pine mushrooms as a proxy for survival and wisdom, a tool for human survival in a world devastated by humankind today.

“Only through precarious survival can we see what went wrong.

Insecurity is the state of recognizing that we are vulnerable to other beings.”

The title of Anna Tsing's "Mushrooms at the End of the World" has two meanings.

Mushrooms exist at the very edge of the capitalist world system, where capital accumulation is difficult to achieve.

Of course, being a peripheral area does not mean that it is outside of capitalism.

Pine mushrooms are so secretly hidden deep in the forest that it is difficult to find them.

On the other hand, it could also imply capitalist ruin, the end of the world.

It also implies the meaning of a crisis situation that will ultimately lead to human greed to extract and accumulate as much as possible from the Earth.

Anna Ching uses the tiny organism known as the pine mushroom as a thread to offer surprising insights into how cooperative survival can emerge in a landscape of capitalist destruction and diversity.

“In this mess we have made,

How else can we explain the fact that something is still alive?”

Developed at the complex intersection of humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences

A poetic and surprisingly rich exploration

In fact, summarizing this book in a few lines is nearly impossible.

This is because the 20 or so stories that the author summarizes as “a colorful gathering” unfold like “mushrooms sprouting up after the rain” (page 8).

Still, this book is incredibly fascinating.

One Amazon review calls the book “dangerously fascinating.”

"The Mushroom at the End of the World" is not a dry social science paper.

The book begins by asking, “How else can we explain the fact that something is still alive in this mess we have made of this world?” (p. 8), and its poetic expressions and subtle depictions of social realities can make you feel like you are reading a novel.

There is no neat conclusion, just a series of sharp observations, analyses, and explanations.

It's filled with surprising accounts of the micro and the macro, the individual and the social—the person feeling the forest floor for traces of pine mushrooms, the energy of mushroom auctions, and the unexpected connections in multinational supply chains.

In the author's encounters with countless people and in the passages where he scans the ground in the pine forest and feels a profound connection with the invisible soil organisms, the reader will also sense how non-human beings (plants, animals, soil, etc.) influence our very existence.

And just like the author, readers can also explore the sensations of smelling, touching, searching, and walking along the pace of mushroom picking.

This is the very same 'art of awareness' that artists use to discover the world.

Professor Noh Go-un, who translated it into Korean, presented a topic on ‘ecology’ with Anna Ching at the 2017 Korean Cultural Anthropology Association conference.

The translator has successfully captured the author's unique prose style in Korean, conveying the original text's precise meaning and rich nuances.

It's really original.

…this book transforms the trade and ecology of the extremely rare pine mushroom into a fascinating modern fable about post-industrial survival and environmental regeneration.

―The Guardian

Anna Ching weaves an adventurous tale.

…his passionate account of the intersecting cultures and the resilience of nature offers a fresh perspective on modernity and progress.

―Publisher's Weekly

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 30, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 544 pages | 782g | 140*210*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788965642855

- ISBN10: 896564285X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)