Price of 1 degree

|

Description

Book Introduction

"It was too hot, so I failed the test!" isn't an excuse; it's science.

From morning coffee to the rise and fall of nations, a Wharton School economist's unconventional take on climate change.

The important question now is not whether climate change is real, but whether we can adapt to the climate change that has already occurred.

Professor Ji-Sung Park, a Wharton School environmental economist and a prominent Korean scholar whose work has been consulted by Bill Gates, presents a new lens through which to view climate change based on his long-term research.

In his controversial debut work, The Price of One Degree, he uses powerful evidence obtained through analyzing numerous statistics to illuminate the gradual damage caused by climate change that we have not yet recognized, while at the same time presenting a new perspective and proactive hope for overcoming it.

A compilation of cutting-edge research on climate change, focusing on the invisible but real costs of climate change. Rather than issuing provocative warnings, it boldly exposes the reality of climate change today through dry datasets and statistics.

This book is not just a climate report.

It does not follow simple logic such as “It is too late now because it has exceeded 1.5 degrees” or “There is no need to worry because this level of change has always happened.”

What takes its place is economic analysis validated with tens of millions of data sets.

Let's pay attention to the subtle, gradual, yet real damage statistics that have been overshadowed by extreme disasters like wildfires, heat waves, and typhoons.

Whether you're a climate doomsday believer or a skeptic, this book is ultimately about all of us.

From morning coffee to the rise and fall of nations, a Wharton School economist's unconventional take on climate change.

The important question now is not whether climate change is real, but whether we can adapt to the climate change that has already occurred.

Professor Ji-Sung Park, a Wharton School environmental economist and a prominent Korean scholar whose work has been consulted by Bill Gates, presents a new lens through which to view climate change based on his long-term research.

In his controversial debut work, The Price of One Degree, he uses powerful evidence obtained through analyzing numerous statistics to illuminate the gradual damage caused by climate change that we have not yet recognized, while at the same time presenting a new perspective and proactive hope for overcoming it.

A compilation of cutting-edge research on climate change, focusing on the invisible but real costs of climate change. Rather than issuing provocative warnings, it boldly exposes the reality of climate change today through dry datasets and statistics.

This book is not just a climate report.

It does not follow simple logic such as “It is too late now because it has exceeded 1.5 degrees” or “There is no need to worry because this level of change has always happened.”

What takes its place is economic analysis validated with tens of millions of data sets.

Let's pay attention to the subtle, gradual, yet real damage statistics that have been overshadowed by extreme disasters like wildfires, heat waves, and typhoons.

Whether you're a climate doomsday believer or a skeptic, this book is ultimately about all of us.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface to the Korean edition

Entering

Part 1

Chapter 1: Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow

Chapter 2 Physical Capital and Human Capital

Chapter 3: The Subtle Disaster Revealed by Smoke

Part 2

Chapter 4: Causality of Data

Chapter 5: How Heat Waves Destroy Lives

Chapter 6: The Relationship Between Temperature and Local Area

Chapter 7 Peace and Tranquility in a Boiling World

Part 3

Chapter 8: Climate Change and Income Polarization

Chapter 9: Climate Inequality in Everyday Life

Chapter 10: Why We're Vulnerable to Change

Part 4

Chapter 11 It's Not Too Late

Chapter 12 Beyond the Silver Bullet

Going out: All living things in nature

Acknowledgements

References

Entering

Part 1

Chapter 1: Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow

Chapter 2 Physical Capital and Human Capital

Chapter 3: The Subtle Disaster Revealed by Smoke

Part 2

Chapter 4: Causality of Data

Chapter 5: How Heat Waves Destroy Lives

Chapter 6: The Relationship Between Temperature and Local Area

Chapter 7 Peace and Tranquility in a Boiling World

Part 3

Chapter 8: Climate Change and Income Polarization

Chapter 9: Climate Inequality in Everyday Life

Chapter 10: Why We're Vulnerable to Change

Part 4

Chapter 11 It's Not Too Late

Chapter 12 Beyond the Silver Bullet

Going out: All living things in nature

Acknowledgements

References

Detailed image

Into the book

If it feels depressingly familiar to begin a book about climate change with a story about a natural disaster, it's because we use that rhetoric a lot.

The conversations we have about climate change too often focus on disaster scenarios, fueling fear and despair, with an underlying sense of impending catastrophe.

They say things like, "This is your last chance," or, even worse, "You've already crossed the threshold of no return and there's no turning back."

This book challenges that tendency and questions the appropriateness of such a familiar apocalyptic narrative.

It's not that climate change isn't a serious problem.

As we will see, climate change may pose a more insidious threat to human prosperity than many people realize.

But there is growing evidence that our familiar climate catastrophe framework may be missing a crucial part of the real story of climate change.

Ultimately, framing the climate catastrophe as a crisis may actually hinder us from proactively exploring potential solutions.

---From "Entering"

Bringing all the information together to analyze the costs and benefits of climate action—in other words, determining how 1.5 degrees of warming differs from 3 or 4 degrees or more, and how that difference affects the social cost of meeting long-term emissions reduction targets—requires statistical thinking.

(Furthermore, identifying cause and effect among multiple, potentially interrelated causal factors may require reliable methods, as well as a means of quantifying many important aspects of human experience that are not easily quantifiable.) Of course, human intuition is a surprisingly powerful tool.

It can be incredibly powerful, especially when given the right input and training in the right context.

The more intuitive System 1 is usually very good at making connections between familiar objects and judging what is and is not a fair outcome.

Moreover, after an initial training period, you can become skilled enough to easily perform fairly complex tasks, such as tying your shoelaces, diagnosing a tumor, or composing a sonata.

However, intuition is usually reliable only when you have accumulated experience making judgments in predictable environments.

---From "Chapter 1 | Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow"

The core of the story is the acting.

What if, in terms of the social costs of today's wildfires, smoke might be the single most damaging factor, in terms of its cumulative impacts on learning, productivity, and health? Moreover, what if the damage caused by smoke extends beyond Los Angeles, California, or even the American West, affecting people in Boston, Chicago, Montreal, and Mexico City, with varying degrees of severity? Similarly, what if the hidden costs of global warming are equivalent to several times the combined annual profits of Fortune 500 companies, resulting in social and economic losses? 2 And what if slightly higher temperatures have subtle yet far-reaching health impacts that far exceed those of all other natural disasters combined, exacerbating the forces that drive inequality in the modern economy? What if it's "smoke," not the fires, that ultimately kills more people?

---From "Chapter 3 | The Subtle Disaster Revealed by Acting"

It may have been the cause of the deaths of about 10,000 elderly people every year.

That's a much higher number than the official figures, which state that 700 to 800 people die annually from the entire U.S. population.

These estimates suggest that climate change may lead to a sharp increase in elderly mortality in the future.

To reiterate, the marginal effects of these less extreme but more frequent weather events, which collectively affect more people, have received relatively little attention in the climate change puzzle.

In reality, even in the wealthiest and most air-conditioned countries on Earth, this relatively ordinary heat can kill tens of thousands of people each year.

---From "Chapter 5 | How Heat Waves Destroy Lives"

He looked at daily temperature data for the area from 1980 to 2009 and found that across a wide range of crime types, higher daily temperatures were associated with more crime occurring that month.

When temperatures exceeded 32.2 degrees Celsius for a week, the monthly rape rate increased by more than 5 percent, and murder and aggravated assault increased by about 3 percent.

What makes this relationship a little more causal is that the researchers didn't compare crime rates in hot and cold regions, but rather looked at long-term changes in temperature and crime rates within specific counties.

This effect is not trivial.

Ranson estimates that climate change could lead to more than a million additional aggravated assaults and nearly 200,000 additional rapes in the United States during the 21st century if the number of hot days increases.

Citing other research that found that increasing a city's police force size by 1 percent reduces violent crime by 0.3 percent, he argued that to offset the effects of climate change on crime, the size of the U.S. police force must increase by at least 4 percent now and maintain that increase.

---From "Chapter 7 | Peace and Tranquility in a Boiling World"

The patterns that emerge from these studies are puzzling.

As previously described, rising temperatures not only have noticeable impacts on human health, life, and economic productivity, but can also have broader, more invisible negative impacts on mental health and overall quality of life.

If measurement difficulties associated with traditional datasets have been a problem in the context of heat and mortality or heat and labor productivity, the problem may be even more severe in this case.

Many of these impacts are nearly impossible to document on a case-by-case basis.

As noted in Chapter 2, the importance of non-market climate costs is often not captured in official statistics.

Only by examining larger populations and carefully controlling for potentially widespread spurious correlations can we truly detect the insidious impact of heat on the mind.

---From "Chapter 7 | Peace and Tranquility in a Boiling World"

The phenomenon of labor market performance being divided within a country is by no means unique to the United States or Korea.

The United States has long been one of the OECD countries with the highest levels of inequality, and inequality has become increasingly severe over the past several decades.

However, similar trends, although not on a similar scale, have been recorded in other advanced countries.

Germany, New Zealand, Canada, Italy and the United Kingdom all saw significant increases in their Gini coefficients, which measure the degree of income inequality within a country, during this period.

As mentioned earlier, China has also experienced rapid increases in inter-individual inequality over the past few decades.

In India, the top 10 percent's share of income increased from 30 percent in the 1980s to 56 percent in 2020.

What causes such economic polarization remains a hotly debated topic.

One common feature across many countries is technological change.

And a key issue is how technological change affects workers with varying levels of formal education and training.

It is a growing consensus among scholars that technological advancements both increase and decrease the demand for certain occupations.

Economists Darren Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo estimate that more than 50 percent of the changes in the wage structure in the United States are due to automation and various forms of technological change.

As economist David Autor puts it, “Almost every country has had to experience this phenomenon in some form.

“It’s just that some countries have done a little better at stopping it.”

---From "Chapter 8 | Climate Change and Income Polarization"

The scale of adaptation funding desired and the actual transfer of adaptation funding from the Global North to the Global South are often debated.

However, there is little discussion about the moral justification for resource transfers between the Global North and the Global South.

It is difficult to dispute the ethical persuasiveness of the argument previously presented by UN Secretary-General Guterres, as inequalities in emissions and economic performance are likely to be exacerbated by climate change.

But have we ever seriously considered how such funds should be used? Should they be funneled into the bank accounts of the world's poor? Let's set aside the question of whether those most in need have bank accounts.

Because the challenge of adaptation is so enormous and requires mobilizing all of our economic power to address it, as global warming progresses, it may become increasingly important not just to know who is most vulnerable, but also why they are vulnerable and what adaptation policy options to choose from.

But answers to such crucial questions have remained shrouded in uncertainty.

---From "Chapter 10 | Why We Are Vulnerable to Change"

But there are also growing reasons for optimism.

As mentioned, the world has already undergone a significant shift, a shift that has become particularly evident over the past few decades. Total carbon dioxide emissions within the EU peaked at around 4 gigatons and then fell to below 2.8 gigatons in 2022, a decline of nearly 30 percent.

Per capita emissions have fallen by more than 35 percent, from 11 tonnes per person in 1990 to less than 7 tonnes per person in 2022.39 In 2021, the Tesla Model 3 was the second-best-selling new car in the UK.

It's not just the second-best-selling electric car, it's the second-best-selling new car of all time.

In the same year, about 80 percent of new passenger cars sold in Norway were purely electric.

The United States' performance over a similar period has been less impressive, but it has still reduced its carbon dioxide emissions by 8 percent (1990-2020) and, with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), has set out to cut emissions by nearly half by 2030 compared to 2005 levels.

Even in developing countries, there have been significant achievements despite steady increases in emissions.

For example, over the past 15 years, more new solar and wind power plants have been built in India than in Australia, the UK and the Netherlands combined.

---From "Chapter 11 | It's Not Too Late"

Another significant advance is occurring in how we target vulnerable individuals and communities.

Since COVID-19, countries have scrambled to prevent job losses and economic collapse, relying on policy tools like the U.S. payroll protection program.

While the payroll protection program saved many jobs, the high costs ultimately fell on the government and taxpayers due to the lack of precise targeting.

According to research by scholars including David Autor, for every dollar of wage relief provided by paycheck guarantee programs, $3.13 was spent.

The cost of saving one job for one year was estimated at $169,300, which is significantly higher than the average salary for that job ($58,200).

While the paycheck protection program was successful in preventing job losses during the pandemic, it came at a high financial cost.

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of accurate target selection and efficient resource allocation in policy design.

The conversations we have about climate change too often focus on disaster scenarios, fueling fear and despair, with an underlying sense of impending catastrophe.

They say things like, "This is your last chance," or, even worse, "You've already crossed the threshold of no return and there's no turning back."

This book challenges that tendency and questions the appropriateness of such a familiar apocalyptic narrative.

It's not that climate change isn't a serious problem.

As we will see, climate change may pose a more insidious threat to human prosperity than many people realize.

But there is growing evidence that our familiar climate catastrophe framework may be missing a crucial part of the real story of climate change.

Ultimately, framing the climate catastrophe as a crisis may actually hinder us from proactively exploring potential solutions.

---From "Entering"

Bringing all the information together to analyze the costs and benefits of climate action—in other words, determining how 1.5 degrees of warming differs from 3 or 4 degrees or more, and how that difference affects the social cost of meeting long-term emissions reduction targets—requires statistical thinking.

(Furthermore, identifying cause and effect among multiple, potentially interrelated causal factors may require reliable methods, as well as a means of quantifying many important aspects of human experience that are not easily quantifiable.) Of course, human intuition is a surprisingly powerful tool.

It can be incredibly powerful, especially when given the right input and training in the right context.

The more intuitive System 1 is usually very good at making connections between familiar objects and judging what is and is not a fair outcome.

Moreover, after an initial training period, you can become skilled enough to easily perform fairly complex tasks, such as tying your shoelaces, diagnosing a tumor, or composing a sonata.

However, intuition is usually reliable only when you have accumulated experience making judgments in predictable environments.

---From "Chapter 1 | Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow"

The core of the story is the acting.

What if, in terms of the social costs of today's wildfires, smoke might be the single most damaging factor, in terms of its cumulative impacts on learning, productivity, and health? Moreover, what if the damage caused by smoke extends beyond Los Angeles, California, or even the American West, affecting people in Boston, Chicago, Montreal, and Mexico City, with varying degrees of severity? Similarly, what if the hidden costs of global warming are equivalent to several times the combined annual profits of Fortune 500 companies, resulting in social and economic losses? 2 And what if slightly higher temperatures have subtle yet far-reaching health impacts that far exceed those of all other natural disasters combined, exacerbating the forces that drive inequality in the modern economy? What if it's "smoke," not the fires, that ultimately kills more people?

---From "Chapter 3 | The Subtle Disaster Revealed by Acting"

It may have been the cause of the deaths of about 10,000 elderly people every year.

That's a much higher number than the official figures, which state that 700 to 800 people die annually from the entire U.S. population.

These estimates suggest that climate change may lead to a sharp increase in elderly mortality in the future.

To reiterate, the marginal effects of these less extreme but more frequent weather events, which collectively affect more people, have received relatively little attention in the climate change puzzle.

In reality, even in the wealthiest and most air-conditioned countries on Earth, this relatively ordinary heat can kill tens of thousands of people each year.

---From "Chapter 5 | How Heat Waves Destroy Lives"

He looked at daily temperature data for the area from 1980 to 2009 and found that across a wide range of crime types, higher daily temperatures were associated with more crime occurring that month.

When temperatures exceeded 32.2 degrees Celsius for a week, the monthly rape rate increased by more than 5 percent, and murder and aggravated assault increased by about 3 percent.

What makes this relationship a little more causal is that the researchers didn't compare crime rates in hot and cold regions, but rather looked at long-term changes in temperature and crime rates within specific counties.

This effect is not trivial.

Ranson estimates that climate change could lead to more than a million additional aggravated assaults and nearly 200,000 additional rapes in the United States during the 21st century if the number of hot days increases.

Citing other research that found that increasing a city's police force size by 1 percent reduces violent crime by 0.3 percent, he argued that to offset the effects of climate change on crime, the size of the U.S. police force must increase by at least 4 percent now and maintain that increase.

---From "Chapter 7 | Peace and Tranquility in a Boiling World"

The patterns that emerge from these studies are puzzling.

As previously described, rising temperatures not only have noticeable impacts on human health, life, and economic productivity, but can also have broader, more invisible negative impacts on mental health and overall quality of life.

If measurement difficulties associated with traditional datasets have been a problem in the context of heat and mortality or heat and labor productivity, the problem may be even more severe in this case.

Many of these impacts are nearly impossible to document on a case-by-case basis.

As noted in Chapter 2, the importance of non-market climate costs is often not captured in official statistics.

Only by examining larger populations and carefully controlling for potentially widespread spurious correlations can we truly detect the insidious impact of heat on the mind.

---From "Chapter 7 | Peace and Tranquility in a Boiling World"

The phenomenon of labor market performance being divided within a country is by no means unique to the United States or Korea.

The United States has long been one of the OECD countries with the highest levels of inequality, and inequality has become increasingly severe over the past several decades.

However, similar trends, although not on a similar scale, have been recorded in other advanced countries.

Germany, New Zealand, Canada, Italy and the United Kingdom all saw significant increases in their Gini coefficients, which measure the degree of income inequality within a country, during this period.

As mentioned earlier, China has also experienced rapid increases in inter-individual inequality over the past few decades.

In India, the top 10 percent's share of income increased from 30 percent in the 1980s to 56 percent in 2020.

What causes such economic polarization remains a hotly debated topic.

One common feature across many countries is technological change.

And a key issue is how technological change affects workers with varying levels of formal education and training.

It is a growing consensus among scholars that technological advancements both increase and decrease the demand for certain occupations.

Economists Darren Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo estimate that more than 50 percent of the changes in the wage structure in the United States are due to automation and various forms of technological change.

As economist David Autor puts it, “Almost every country has had to experience this phenomenon in some form.

“It’s just that some countries have done a little better at stopping it.”

---From "Chapter 8 | Climate Change and Income Polarization"

The scale of adaptation funding desired and the actual transfer of adaptation funding from the Global North to the Global South are often debated.

However, there is little discussion about the moral justification for resource transfers between the Global North and the Global South.

It is difficult to dispute the ethical persuasiveness of the argument previously presented by UN Secretary-General Guterres, as inequalities in emissions and economic performance are likely to be exacerbated by climate change.

But have we ever seriously considered how such funds should be used? Should they be funneled into the bank accounts of the world's poor? Let's set aside the question of whether those most in need have bank accounts.

Because the challenge of adaptation is so enormous and requires mobilizing all of our economic power to address it, as global warming progresses, it may become increasingly important not just to know who is most vulnerable, but also why they are vulnerable and what adaptation policy options to choose from.

But answers to such crucial questions have remained shrouded in uncertainty.

---From "Chapter 10 | Why We Are Vulnerable to Change"

But there are also growing reasons for optimism.

As mentioned, the world has already undergone a significant shift, a shift that has become particularly evident over the past few decades. Total carbon dioxide emissions within the EU peaked at around 4 gigatons and then fell to below 2.8 gigatons in 2022, a decline of nearly 30 percent.

Per capita emissions have fallen by more than 35 percent, from 11 tonnes per person in 1990 to less than 7 tonnes per person in 2022.39 In 2021, the Tesla Model 3 was the second-best-selling new car in the UK.

It's not just the second-best-selling electric car, it's the second-best-selling new car of all time.

In the same year, about 80 percent of new passenger cars sold in Norway were purely electric.

The United States' performance over a similar period has been less impressive, but it has still reduced its carbon dioxide emissions by 8 percent (1990-2020) and, with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), has set out to cut emissions by nearly half by 2030 compared to 2005 levels.

Even in developing countries, there have been significant achievements despite steady increases in emissions.

For example, over the past 15 years, more new solar and wind power plants have been built in India than in Australia, the UK and the Netherlands combined.

---From "Chapter 11 | It's Not Too Late"

Another significant advance is occurring in how we target vulnerable individuals and communities.

Since COVID-19, countries have scrambled to prevent job losses and economic collapse, relying on policy tools like the U.S. payroll protection program.

While the payroll protection program saved many jobs, the high costs ultimately fell on the government and taxpayers due to the lack of precise targeting.

According to research by scholars including David Autor, for every dollar of wage relief provided by paycheck guarantee programs, $3.13 was spent.

The cost of saving one job for one year was estimated at $169,300, which is significantly higher than the average salary for that job ($58,200).

While the paycheck protection program was successful in preventing job losses during the pandemic, it came at a high financial cost.

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of accurate target selection and efficient resource allocation in policy design.

---From "Chapter 12 | Beyond the Silver Bullet"

Publisher's Review

★“A work that seeks sustainability for the Earth and humanity through rigorous statistics!” ―Hong Jong-ho

★“I have developed a cool-headed resolve, compassion for the vulnerable, and a positive sense of hope.” ―Lee Jeong-mo

★Let's not despair or ignore it.

A Wharton School Economist's Unconventional Reading on Climate Change

“Climate Change: How Can We Adapt and Survive?”

A bold analysis of climate change by Professor Ji-Sung Park, a rising Korean economist at Wharton School! Do you consider climate change a disaster or are you trying to ignore it? It no longer matters which side you're on.

Climate change has been on our minds for a long time.

From politicians to businesspeople, from doomsayers to skeptics, everyone has their own scenarios and debates about 1.5 degrees Celsius as the 'tipping point'.

I had no choice but to listen to the opinions of many 'experts'.

But recently, it has started to irritate my eyes and skin.

The magical '1.5 degrees' has been reached faster than expected, natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, and wildfires have become more frequent, and heat waves have become a daily occurrence, making us feel the existential threat.

The important question now is not whether climate change is real, but whether we can adapt to the climate change that has already occurred, and if so, how should we do it?

Ji-Sung Park, a professor of public economics at the Wharton School, presents a new lens through which to view climate change through long-term research.

From the perspective of an econometrician, it provides an answer to the question, ‘How to adapt?’

After compiling the latest research on climate change, the author boldly exposes the reality of climate change today through dry datasets and statistics rather than provocative warnings.

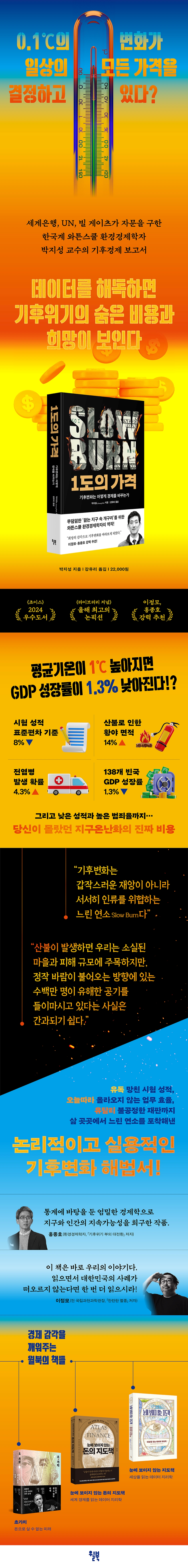

"It was too hot, so I failed the test!" isn't an excuse, it's science. The power of data to reveal the hidden costs and hopes of climate change.

In January 2025, the largest wildfire in 40 years broke out in Los Angeles, USA, burning an area 50 times the size of Yeouido and forcing hundreds of thousands of residents to evacuate.

The damage alone is expected to exceed at least 400 trillion won, and the entire world has sent a helping hand to the tragedy that struck LA.

Although the damage was enormous, the wildfires appeared to be subsiding after three weeks.

Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement (an agreement aimed at limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels) as if it were nothing.

In this way, the discourse on climate change often flows into two extremes.

On one side, they cry out for an 'irreversible end', while on the other side, they promote 'blind optimism that we can adapt'.

But The Price of One Degree breaks away from these two approaches and shows us the impacts of climate change that we hadn't even considered.

While the damage from natural disasters like large-scale wildfires is visible in numbers, the subtle damage caused by natural disasters, the subtle changes we don't perceive as threats, can drastically change our daily lives.

If your child's test scores drop one day, it may not be because they're particularly bad at studying, but because of climate change.

When schooling becomes difficult due to a natural disaster, this significantly lowers the future income expectations of individual students.

This is shown in the educational completion rate and academic achievement leading to a degree, and after collecting, analyzing and researching a large amount of data, the author found that in the case of a large-scale natural disaster (physical capital damage of more than $500 per person), human capital damage occurs approximately $1,520.

Moreover, it has been revealed that work efficiency decreases on unusually hot days, and for every additional day of heatwave (temperatures above 32.2 degrees Celsius), the number of deaths in the United States increases by 3,000, and low-income people are more exposed to this heat and are vulnerable to climate change.

Additionally, on days when the temperature is above 29 degrees, the probability of violent crime is 9 percent higher than on cooler days.

In this way, climate change affects society in unexpected ways.

Furthermore, this book examines various cases from various angles, such as the health (national power) gap between those (countries) who can afford to purchase air conditioners and those (countries) who cannot, the impact of heat waves on labor productivity, and the issue of climate migration.

This book does not stop at showing statistics produced based on various data, but also covers everything from individuals to institutions.

It presents the roles that various classes can play, ranging from the basic to the advanced.

Through a new framework that views the climate crisis from an economic perspective, readers will realize that climate change is not simply an environmental issue, but is closely connected to economic decision-making and policy-making processes, as well as to the problems we face in our daily lives.

"How can we make better choices?" The equation of existential choices for survival, from individuals to societies.

As seen in Trump's announcement of withdrawal from the Paris Agreement as soon as he took office as president, the global collective task of 'overcoming the climate crisis' is facing difficulties.

The situation in our country is not favorable either.

The Carbon Neutrality Basic Act, which includes a clause to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions to '0' by 2050, was ruled to infringe on the fundamental rights (environmental rights) of future generations, and the law must be revised immediately to include more precise and detailed goals by February 2026.

This book, which analyzes the complex and subtle damage caused by climate change through data-driven economics, offers significant implications for establishing sustainable policies.

Some criticize economics as a tool of capitalism, but economics is also powerful in solving social problems.

It can be a tool.

Alfred Marshall, the father of economics, said this:

“Keep your head cool, but your heart warm.” This means that while you should coolly analyze social phenomena with a cool head, the results of that analysis should be directed toward universal human values.

In that sense, this book is exactly in line with Marshall's words.

This book analyzes the climate crisis from an economic perspective and will help individuals and governments alike explore realistic response measures.

Readers of this book will also find a hopeful message, one that is not pessimistic but realistic, suggesting that we can all be agents of positive change through small choices.

★“I have developed a cool-headed resolve, compassion for the vulnerable, and a positive sense of hope.” ―Lee Jeong-mo

★Let's not despair or ignore it.

A Wharton School Economist's Unconventional Reading on Climate Change

“Climate Change: How Can We Adapt and Survive?”

A bold analysis of climate change by Professor Ji-Sung Park, a rising Korean economist at Wharton School! Do you consider climate change a disaster or are you trying to ignore it? It no longer matters which side you're on.

Climate change has been on our minds for a long time.

From politicians to businesspeople, from doomsayers to skeptics, everyone has their own scenarios and debates about 1.5 degrees Celsius as the 'tipping point'.

I had no choice but to listen to the opinions of many 'experts'.

But recently, it has started to irritate my eyes and skin.

The magical '1.5 degrees' has been reached faster than expected, natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, and wildfires have become more frequent, and heat waves have become a daily occurrence, making us feel the existential threat.

The important question now is not whether climate change is real, but whether we can adapt to the climate change that has already occurred, and if so, how should we do it?

Ji-Sung Park, a professor of public economics at the Wharton School, presents a new lens through which to view climate change through long-term research.

From the perspective of an econometrician, it provides an answer to the question, ‘How to adapt?’

After compiling the latest research on climate change, the author boldly exposes the reality of climate change today through dry datasets and statistics rather than provocative warnings.

"It was too hot, so I failed the test!" isn't an excuse, it's science. The power of data to reveal the hidden costs and hopes of climate change.

In January 2025, the largest wildfire in 40 years broke out in Los Angeles, USA, burning an area 50 times the size of Yeouido and forcing hundreds of thousands of residents to evacuate.

The damage alone is expected to exceed at least 400 trillion won, and the entire world has sent a helping hand to the tragedy that struck LA.

Although the damage was enormous, the wildfires appeared to be subsiding after three weeks.

Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement (an agreement aimed at limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels) as if it were nothing.

In this way, the discourse on climate change often flows into two extremes.

On one side, they cry out for an 'irreversible end', while on the other side, they promote 'blind optimism that we can adapt'.

But The Price of One Degree breaks away from these two approaches and shows us the impacts of climate change that we hadn't even considered.

While the damage from natural disasters like large-scale wildfires is visible in numbers, the subtle damage caused by natural disasters, the subtle changes we don't perceive as threats, can drastically change our daily lives.

If your child's test scores drop one day, it may not be because they're particularly bad at studying, but because of climate change.

When schooling becomes difficult due to a natural disaster, this significantly lowers the future income expectations of individual students.

This is shown in the educational completion rate and academic achievement leading to a degree, and after collecting, analyzing and researching a large amount of data, the author found that in the case of a large-scale natural disaster (physical capital damage of more than $500 per person), human capital damage occurs approximately $1,520.

Moreover, it has been revealed that work efficiency decreases on unusually hot days, and for every additional day of heatwave (temperatures above 32.2 degrees Celsius), the number of deaths in the United States increases by 3,000, and low-income people are more exposed to this heat and are vulnerable to climate change.

Additionally, on days when the temperature is above 29 degrees, the probability of violent crime is 9 percent higher than on cooler days.

In this way, climate change affects society in unexpected ways.

Furthermore, this book examines various cases from various angles, such as the health (national power) gap between those (countries) who can afford to purchase air conditioners and those (countries) who cannot, the impact of heat waves on labor productivity, and the issue of climate migration.

This book does not stop at showing statistics produced based on various data, but also covers everything from individuals to institutions.

It presents the roles that various classes can play, ranging from the basic to the advanced.

Through a new framework that views the climate crisis from an economic perspective, readers will realize that climate change is not simply an environmental issue, but is closely connected to economic decision-making and policy-making processes, as well as to the problems we face in our daily lives.

"How can we make better choices?" The equation of existential choices for survival, from individuals to societies.

As seen in Trump's announcement of withdrawal from the Paris Agreement as soon as he took office as president, the global collective task of 'overcoming the climate crisis' is facing difficulties.

The situation in our country is not favorable either.

The Carbon Neutrality Basic Act, which includes a clause to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions to '0' by 2050, was ruled to infringe on the fundamental rights (environmental rights) of future generations, and the law must be revised immediately to include more precise and detailed goals by February 2026.

This book, which analyzes the complex and subtle damage caused by climate change through data-driven economics, offers significant implications for establishing sustainable policies.

Some criticize economics as a tool of capitalism, but economics is also powerful in solving social problems.

It can be a tool.

Alfred Marshall, the father of economics, said this:

“Keep your head cool, but your heart warm.” This means that while you should coolly analyze social phenomena with a cool head, the results of that analysis should be directed toward universal human values.

In that sense, this book is exactly in line with Marshall's words.

This book analyzes the climate crisis from an economic perspective and will help individuals and governments alike explore realistic response measures.

Readers of this book will also find a hopeful message, one that is not pessimistic but realistic, suggesting that we can all be agents of positive change through small choices.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 14, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 408 pages | 570g | 145*210*26mm

- ISBN13: 9791155818053

- ISBN10: 1155818059

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)