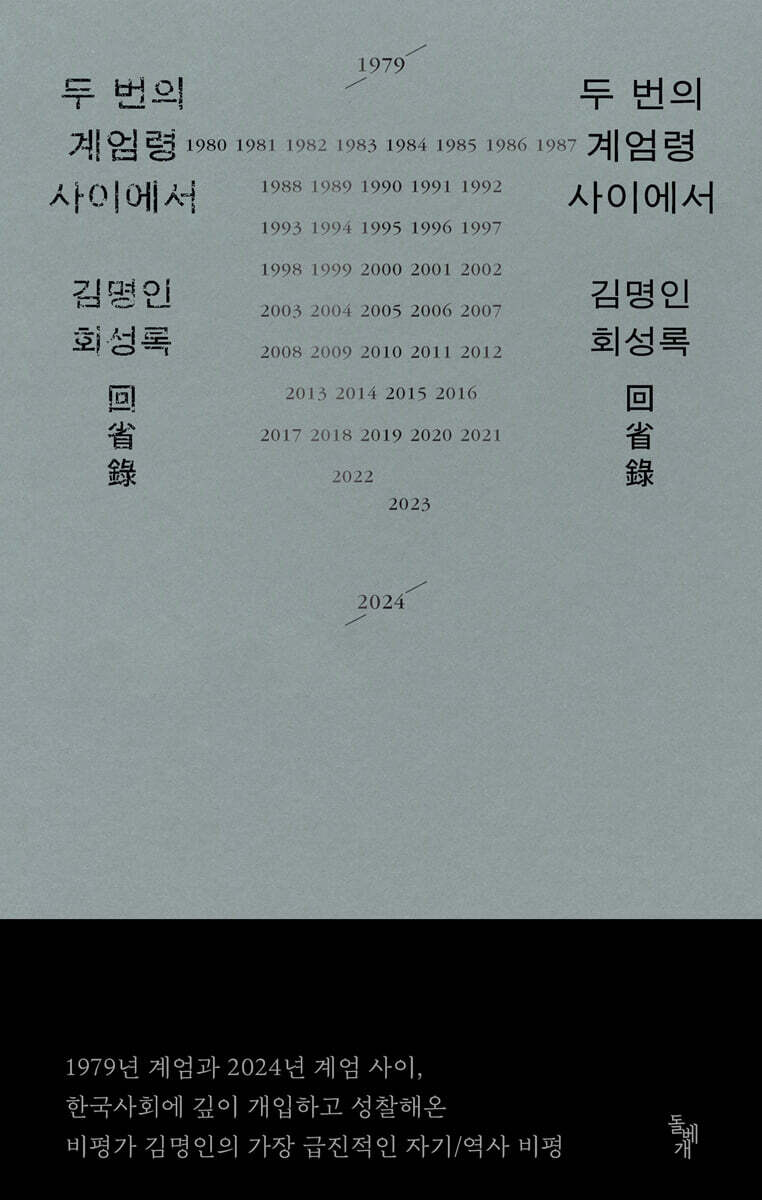

Between two martial laws

|

Description

Book Introduction

Between martial law in 1979 and martial law in 2024,

Deeply involved in and reflecting on Korean society

Critic Kim Myeong-in's most radical self-/historical critique

Critic Kim Myeong-in, who was imprisoned as one of the main instigators of the 1980 “Murim Incident” and was found not guilty in a retrial in 2020, has published “Reflections” (回省錄) “Between Two Martial Laws” in which he conveys “his experiences and thoughts as an old citizen who has wrestled with the past 45 years.”

This book radically deconstructs and reconstructs the memoir genre, combining autobiographical and social historical records while simultaneously attempting radical self-analysis.

From 1977 to 2024, the book meticulously captures the intersection and interpenetration of private experience and public history, offering a comprehensive overview of modern Korean history. Through meticulous self-criticism, it also offers readers a reflective approach to life and an ethics of critical writing that offer rich inspiration.

Deeply involved in and reflecting on Korean society

Critic Kim Myeong-in's most radical self-/historical critique

Critic Kim Myeong-in, who was imprisoned as one of the main instigators of the 1980 “Murim Incident” and was found not guilty in a retrial in 2020, has published “Reflections” (回省錄) “Between Two Martial Laws” in which he conveys “his experiences and thoughts as an old citizen who has wrestled with the past 45 years.”

This book radically deconstructs and reconstructs the memoir genre, combining autobiographical and social historical records while simultaneously attempting radical self-analysis.

From 1977 to 2024, the book meticulously captures the intersection and interpenetration of private experience and public history, offering a comprehensive overview of modern Korean history. Through meticulous self-criticism, it also offers readers a reflective approach to life and an ethics of critical writing that offer rich inspiration.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

To those who read this book

Prologue: From Revolutionary Activist to Citizen

Part 1 My University

Spring 1977, Silence | Academic Society, Another University | A Passage Called Farm Work | That Fall | A Shift in Perception | Becoming a Literary Scholar

Part 2: Forest of Fog, Murim

Before Entering That Forest | Life Above and Below | Park Chung-hee is Dead! | Spring in Seoul | The Withdrawal of Troops | How Will We Remember That Day? | The 'Gwangju Incident' | A Quiet Autumn | Declaration of the Anti-Fascist Student Struggle | In Namyeong-dong, a Scene with Lee Geun-an | Two Years and Seven Months in Prison | Twenty Letters from Prison

Part 3: A Short Dream, a Long Epilogue

Chapter 1: The Transcendence of Worldliness, the Outer Shell of Literature

Entrance Ceremony Procedure | Becoming a Publizer | Becoming a Literary Critic

Chapter 2: The journey ended as the road began.

One desolate winter morning | The dream of "popular national literature" | 1991

Chapter 3: The 1990s: The Life of an Internal Exile

The Beginning of Self-Division | Graduate School | The World Across the River

Chapter 4: Between Disillusionment and Hope

A Return to the Public Sphere? | A Journey with "Hwanghae Culture" | The Profession of a University Professor | Facing a Dystopian Spectacle | The Style of Later Life

Epilogue: History Repeats Itself as Comedy: Martial Law in the Winter of 2024

Americas

Prologue: From Revolutionary Activist to Citizen

Part 1 My University

Spring 1977, Silence | Academic Society, Another University | A Passage Called Farm Work | That Fall | A Shift in Perception | Becoming a Literary Scholar

Part 2: Forest of Fog, Murim

Before Entering That Forest | Life Above and Below | Park Chung-hee is Dead! | Spring in Seoul | The Withdrawal of Troops | How Will We Remember That Day? | The 'Gwangju Incident' | A Quiet Autumn | Declaration of the Anti-Fascist Student Struggle | In Namyeong-dong, a Scene with Lee Geun-an | Two Years and Seven Months in Prison | Twenty Letters from Prison

Part 3: A Short Dream, a Long Epilogue

Chapter 1: The Transcendence of Worldliness, the Outer Shell of Literature

Entrance Ceremony Procedure | Becoming a Publizer | Becoming a Literary Critic

Chapter 2: The journey ended as the road began.

One desolate winter morning | The dream of "popular national literature" | 1991

Chapter 3: The 1990s: The Life of an Internal Exile

The Beginning of Self-Division | Graduate School | The World Across the River

Chapter 4: Between Disillusionment and Hope

A Return to the Public Sphere? | A Journey with "Hwanghae Culture" | The Profession of a University Professor | Facing a Dystopian Spectacle | The Style of Later Life

Epilogue: History Repeats Itself as Comedy: Martial Law in the Winter of 2024

Americas

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

The 'Murim Incident' occurred in 1980, and in 2020, a century later, all charges related to this incident were found not guilty.

At the same time, I, who dreamed of being a revolutionary and thought I had practiced revolutionary activities, ultimately turned out to be nothing more than a young citizen who denounced and resisted the tyranny of some political soldiers who had instigated a civil war.

In other words, I am an old citizen who only gained the right to vote as a citizen in the twilight of my life.

When I finally accepted the not-guilty verdict, and heard that the life-or-death struggles of my youth were in fact fulfilling the rights and duties of a democratic citizen, I was overcome with a strange ambivalence.

--- p.40

The universities of the late 1970s were dead.

(…) The university could not survive without freedom.

How can a conversation be structured and the truth exchanged when all the things you really want to say are hidden deep in your heart?

The 'door to truth' I had been searching for was not in the classroom where I had paid tuition, registered for classes, and entered according to the schedule.

It was rather closer to the Chinese restaurant called 'Okhobulsang' (屋號不祥) outside the school and the musty studio apartment of someone who couldn't even move his feet properly even if only five or six people moved in.

The academic seminars, filled with the smoke of cigarettes, the smell of sweat, and the murmuring of low voices, always turned down to half volume to prevent them from leaking out, were the only way to get close to the truth in those harsh times.

--- p.72

In this way, the social science and philosophy studies I undertook during my first and second years of university became the foundation of my lifelong understanding of the world.

From a constructivist perspective, I may have constructed the world around me from a "leftist perspective" or a "progressive perspective" based on the knowledge I gained from these studies, and I may have wrestled with this constructed world my entire life.

So, was this perception and the life lived based on that perception a kind of fiction?

It may be impossible to perceive 'the world itself'.

But unknowability cannot be reduced to meaninglessness and powerlessness.

Through these studies, I have become someone who cannot endure a life without the romantic impulse to constantly explore the status and meaning of one's own existence and to transcend "this present state," even if change and progress are not the ultimate good.

--- p.89~90

For a long time, when I think of the 'Murim Incident', instead of the historical context or the criticism, the first thing that comes to mind is the bleak morning of January 1, 1981, when it was snowing, the manic fever I felt when I wrote down the 'Anti-Fascist Student Struggle Declaration' in one breath, the image of the detectives wearing black coats and driving a black sedan to arrest me on the gloomy afternoon of December 16, 1980, when it was as if it was going to snow, like the time thieves in Michael Ende's novel 'Momo', the absurdly wide and bone-chilling basement of the Gwanak Police Station in the middle of the night when I had to stand completely naked and recite the entire declaration to prove that I was the author of the declaration, the days of pushing and pulling with torturer Lee Geun-an, who felt like sitting face to face with a huge carnivorous beast, the things that weighed on me for a long time after that, to the point that my official imprisonment of two years and seven months was rather short. The long-lasting shame and guilt, the nightmare of being chased and driven into a dead end, would come rushing in like a tidal wave.

All of these memories were an inseparable part of the 'murim' to me, and a dry or cold record that separates them from the work of looking back on them would not only be impossible for me, but also meaningless.

Therefore, I would like to use the technique of this article to overlap historical context over these memories and images.

--- p.115~116

In 1980, we, the class of '77, were just twenty-two years old. We were forced to live the life of young children under the anti-communist military dictatorship, and somehow had to live by memorizing the "Revolutionary Catechism," but in reality, we were young people with boiling blue blood.

Moreover, it had only been six months since I heard the news that young people of the same age were being killed in Gwangju.

The 'Gwangju Incident' was like an avalanche or a landslide, sweeping away our inner selves and driving us down to death, or something worse than death, and at that time, all we feared was fear itself.

I, and perhaps all of us, at that point, just wanted to accept the stormy fate that was about to strike, as if we had bought a one-way ticket to the execution ground, and not even want to know what would happen tomorrow.

--- p.211

So my wife took care of me for 2 years and 7 months, moving between Yeongdeungpo, Jeonju, and Uijeongbu.

He often boasted about reading 300 books in prison, but all of them were books that his wife had bought with her meager salary or books that he had borrowed from people around him and then returned after giving them to them.

I didn't care about all that hardship and just rolled around comfortably in prison, making all kinds of demands like, "Put this book in here, put that book in here," "Why don't you write letters? When will the visitation come?" And not only that, I even indulged in reckless "old fart" behavior like, "Read this book, read that book," "Live like this, Live like that."

The 'spiritual food' that I had so nobly accumulated within it was actually something that my wife had sowed, nurtured, and collected, and meticulously built and prepared for me.

--- p.306

Perhaps the same was true for most contemporary poets and writers who first read “The Crisis of Intellectual Literature and the Concept of a New National Literature.”

This text, though built on flimsy logic and absurd assertions, was a very fatal text, concealing its bones in a seductive flesh and blood that stimulated the emotions of contemporary writers, both the nostalgia for things that would never come again and the desperate determination for things that must come.

It may sound like self-praise, but I have never been able to write something like that before or since.

Although it was my writing, all I did at the time was that I was chosen by chance to dictate the oracle of the times, that's all.

--- p.369

The 1990s were a time when the entire lives of Koreans began to be reconstructed.

But as I commuted between my home in Seoul and my school in Incheon, I simply observed all these changes of the century, as if watching a fire across a river.

No, in fact, I felt so ashamed of myself for not knowing how to deal with the changes that were taking place, even though I was critically engraving them one by one in my mind, that I could only pretend to be indifferent and expressionless.

For a long time, since I was twenty, I had believed that there was a great movement of the whole in which I participated with all my body and soul, and that a life of moving in the direction it was moving, doing what it told me to do, and fighting for it together with like-minded "comrades" was the "freedom to practice necessity." But I, who had been alone in this world where the "whole" had disappeared and my "comrades" were nowhere to be found, did not know how to intervene.

--- p.413

However, I gradually come to realize that the world is not only a world of logic and reason, a world of seamless mathematics with the six principles of introduction, body, and conclusion, a world of give and take and zero balance, but also a world of so many emotions that cannot find a foothold in that world of logic and reason.

That world is made up of adjectives like 'sadness', 'stuffiness', 'darkness', 'unfairness', 'ambiguity', 'unspeakable', 'suffocation', 'breathtaking', 'joy', 'pleasure', 'affection', 'trustworthiness', and 'comfort'.

And in that world, I think that verb-like words like ‘listen,’ ‘understand,’ ‘help,’ ‘take care of,’ ‘share,’ ‘considerate,’ ‘empathize,’ and ‘join in,’ are what fuel and connect those emotions, giving them names and meaning.

--- p.478

Coincidentally, my life after becoming an adult spanned two periods of martial law and two civil wars, in 1979 and 2024.

Once at the age of twenty-one, and once again at sixty-six, my adult life was marked by martial law and civil war.

But I cried during the civil war when I was twenty-one, and I laughed during the civil war when I was sixty-six.

Marx said this in his book The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

“Hegel once remarked somewhere that all events and figures of great importance in world history repeat themselves.

But he forgot to add:

“The fact that it ends once as a tragedy and once as a comedy.”

At the same time, I, who dreamed of being a revolutionary and thought I had practiced revolutionary activities, ultimately turned out to be nothing more than a young citizen who denounced and resisted the tyranny of some political soldiers who had instigated a civil war.

In other words, I am an old citizen who only gained the right to vote as a citizen in the twilight of my life.

When I finally accepted the not-guilty verdict, and heard that the life-or-death struggles of my youth were in fact fulfilling the rights and duties of a democratic citizen, I was overcome with a strange ambivalence.

--- p.40

The universities of the late 1970s were dead.

(…) The university could not survive without freedom.

How can a conversation be structured and the truth exchanged when all the things you really want to say are hidden deep in your heart?

The 'door to truth' I had been searching for was not in the classroom where I had paid tuition, registered for classes, and entered according to the schedule.

It was rather closer to the Chinese restaurant called 'Okhobulsang' (屋號不祥) outside the school and the musty studio apartment of someone who couldn't even move his feet properly even if only five or six people moved in.

The academic seminars, filled with the smoke of cigarettes, the smell of sweat, and the murmuring of low voices, always turned down to half volume to prevent them from leaking out, were the only way to get close to the truth in those harsh times.

--- p.72

In this way, the social science and philosophy studies I undertook during my first and second years of university became the foundation of my lifelong understanding of the world.

From a constructivist perspective, I may have constructed the world around me from a "leftist perspective" or a "progressive perspective" based on the knowledge I gained from these studies, and I may have wrestled with this constructed world my entire life.

So, was this perception and the life lived based on that perception a kind of fiction?

It may be impossible to perceive 'the world itself'.

But unknowability cannot be reduced to meaninglessness and powerlessness.

Through these studies, I have become someone who cannot endure a life without the romantic impulse to constantly explore the status and meaning of one's own existence and to transcend "this present state," even if change and progress are not the ultimate good.

--- p.89~90

For a long time, when I think of the 'Murim Incident', instead of the historical context or the criticism, the first thing that comes to mind is the bleak morning of January 1, 1981, when it was snowing, the manic fever I felt when I wrote down the 'Anti-Fascist Student Struggle Declaration' in one breath, the image of the detectives wearing black coats and driving a black sedan to arrest me on the gloomy afternoon of December 16, 1980, when it was as if it was going to snow, like the time thieves in Michael Ende's novel 'Momo', the absurdly wide and bone-chilling basement of the Gwanak Police Station in the middle of the night when I had to stand completely naked and recite the entire declaration to prove that I was the author of the declaration, the days of pushing and pulling with torturer Lee Geun-an, who felt like sitting face to face with a huge carnivorous beast, the things that weighed on me for a long time after that, to the point that my official imprisonment of two years and seven months was rather short. The long-lasting shame and guilt, the nightmare of being chased and driven into a dead end, would come rushing in like a tidal wave.

All of these memories were an inseparable part of the 'murim' to me, and a dry or cold record that separates them from the work of looking back on them would not only be impossible for me, but also meaningless.

Therefore, I would like to use the technique of this article to overlap historical context over these memories and images.

--- p.115~116

In 1980, we, the class of '77, were just twenty-two years old. We were forced to live the life of young children under the anti-communist military dictatorship, and somehow had to live by memorizing the "Revolutionary Catechism," but in reality, we were young people with boiling blue blood.

Moreover, it had only been six months since I heard the news that young people of the same age were being killed in Gwangju.

The 'Gwangju Incident' was like an avalanche or a landslide, sweeping away our inner selves and driving us down to death, or something worse than death, and at that time, all we feared was fear itself.

I, and perhaps all of us, at that point, just wanted to accept the stormy fate that was about to strike, as if we had bought a one-way ticket to the execution ground, and not even want to know what would happen tomorrow.

--- p.211

So my wife took care of me for 2 years and 7 months, moving between Yeongdeungpo, Jeonju, and Uijeongbu.

He often boasted about reading 300 books in prison, but all of them were books that his wife had bought with her meager salary or books that he had borrowed from people around him and then returned after giving them to them.

I didn't care about all that hardship and just rolled around comfortably in prison, making all kinds of demands like, "Put this book in here, put that book in here," "Why don't you write letters? When will the visitation come?" And not only that, I even indulged in reckless "old fart" behavior like, "Read this book, read that book," "Live like this, Live like that."

The 'spiritual food' that I had so nobly accumulated within it was actually something that my wife had sowed, nurtured, and collected, and meticulously built and prepared for me.

--- p.306

Perhaps the same was true for most contemporary poets and writers who first read “The Crisis of Intellectual Literature and the Concept of a New National Literature.”

This text, though built on flimsy logic and absurd assertions, was a very fatal text, concealing its bones in a seductive flesh and blood that stimulated the emotions of contemporary writers, both the nostalgia for things that would never come again and the desperate determination for things that must come.

It may sound like self-praise, but I have never been able to write something like that before or since.

Although it was my writing, all I did at the time was that I was chosen by chance to dictate the oracle of the times, that's all.

--- p.369

The 1990s were a time when the entire lives of Koreans began to be reconstructed.

But as I commuted between my home in Seoul and my school in Incheon, I simply observed all these changes of the century, as if watching a fire across a river.

No, in fact, I felt so ashamed of myself for not knowing how to deal with the changes that were taking place, even though I was critically engraving them one by one in my mind, that I could only pretend to be indifferent and expressionless.

For a long time, since I was twenty, I had believed that there was a great movement of the whole in which I participated with all my body and soul, and that a life of moving in the direction it was moving, doing what it told me to do, and fighting for it together with like-minded "comrades" was the "freedom to practice necessity." But I, who had been alone in this world where the "whole" had disappeared and my "comrades" were nowhere to be found, did not know how to intervene.

--- p.413

However, I gradually come to realize that the world is not only a world of logic and reason, a world of seamless mathematics with the six principles of introduction, body, and conclusion, a world of give and take and zero balance, but also a world of so many emotions that cannot find a foothold in that world of logic and reason.

That world is made up of adjectives like 'sadness', 'stuffiness', 'darkness', 'unfairness', 'ambiguity', 'unspeakable', 'suffocation', 'breathtaking', 'joy', 'pleasure', 'affection', 'trustworthiness', and 'comfort'.

And in that world, I think that verb-like words like ‘listen,’ ‘understand,’ ‘help,’ ‘take care of,’ ‘share,’ ‘considerate,’ ‘empathize,’ and ‘join in,’ are what fuel and connect those emotions, giving them names and meaning.

--- p.478

Coincidentally, my life after becoming an adult spanned two periods of martial law and two civil wars, in 1979 and 2024.

Once at the age of twenty-one, and once again at sixty-six, my adult life was marked by martial law and civil war.

But I cried during the civil war when I was twenty-one, and I laughed during the civil war when I was sixty-six.

Marx said this in his book The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

“Hegel once remarked somewhere that all events and figures of great importance in world history repeat themselves.

But he forgot to add:

“The fact that it ends once as a tragedy and once as a comedy.”

--- p.486

Publisher's Review

“From now on, I am a self-proclaimed revolutionary activist.

I will tell you the long story of how I came to stand in the position of a citizen.”

Between martial law in 1979 and 2024, or 40 years after the Murim Incident

Critic Kim Myeong-in, who was imprisoned as one of the masterminds of the 'Murim Incident' in 1980 and was found not guilty in a retrial in 2020, 40 years later, published 'Hoeseongnok' (回省錄) 'Between Two Martial Laws', which conveys "the experiences and thoughts of an old citizen who has wrestled with the past 45 years" (p. 41), as "a record of reflection from a past generation to today's young generation and a proposal of empathy and solidarity extended with a shameful hand" (p. 16).

The 'Murim Incident' was an anti-government protest that occurred on the campus of Seoul National University on December 11, 1980.

This became a "public security incident" under the military regime, with many people involved being sentenced to prison or forcibly conscripted, and it caused great repercussions in the history of the student movement in the 1980s and in modern Korean history.

This book began with the intention of compiling a report with historical value on the "Murim Incident" at the request of attorney Lee Myeong-chun, who was the defense attorney during the retrial process. However, it took on its current format following the author's suggestion to expand it to "record in detail the entire story of the student movement incident called the Moorim Incident that took place in 1980, but reinterpret the changes in Korean society over the 40 years leading up to its official evaluation changing from a leftist communist crime to a legitimate act of civil resistance, within the context of the twists and turns of one man's life" (p. 13).

Meanwhile, while writing this book, the author constantly felt that “the 40 years of his life after coming of age were a dark landscape colored entirely with ‘romantic melancholy,’” but in December 2024, while he was in the final stages of work, he experienced martial law for the first time in 45 years.

“On October 26, 1979, when I was in my early twenties, I experienced the martial law declared with the assassination of Park Chung-hee, and the military rebellion by Chun Doo-hwan and his group on December 12 of that year. In the winter of 2024, when I was in my late sixties, I was caught up in the whirlpool of another martial law.

Like a tightrope walker straddling a rope between two poles, I spent my entire adult life precariously crossing these two martial laws.

However, the long-term depression that began with the martial law I experienced in my early twenties surprisingly disappeared as I experienced this comical martial law in my later years and the amazing struggle of young citizens against it.” (p. 15) And the title of this book became ‘Between Two Martial Laws.’

The author continues:

“The new title may contain some melancholy, but through it, I have finally been able to positively accept my life, which has been tossed and turned like waves by the dynamics of modern Korean history, which does not easily allow for either pessimism or optimism.”

A dazzling combination of autobiographical and socio-historical records

In 『Between Two Martial Laws』, ‘individual life’ and ‘modern Korean history’ cannot be separated, and ‘autobiographical records’ and ‘social historical records’ are tightly intertwined.

Therefore, reading this book means reading the 'history' engraved in the life of an individual who has thought most intensely about Korean society.

The author wrote:

“From now on, I will tell you the long story of how a self-proclaimed revolutionary came to stand as a citizen.

This long story contains the details of what happened to me, to Korean society, and to the world during that long period of time, what I thought, what I did, and what I failed to do while going through those things.

(…) However, I intend to tell this story with the hope that it will be both an autobiographical account of one individual and a social historical record that will allow us to look into how Korean society has changed over the past 45 years.” (p. 41)

Since the late 1970s, which is also the author's entire adult life, he has been actively involved in key moments in modern Korean history and critically reflecting on their impact on daily life and society.

In December 1980, Kim Myeong-in, a senior in the Department of Korean Language and Literature at Seoul National University who wrote the document titled “Anti-Fascist Student Struggle Declaration,” was taken away by detectives on the grounds that he was the instigator of the “Murim Incident.” He was subjected to illegal interrogation involving inhumane torture and imprisoned for two years and seven months as a “leftist” for violating the Anti-Communist Act and Martial Law.

Afterwards, he worked as an employee at a small trading agency and then as editor-in-chief of the humanities and social sciences publishing company ‘Pulbit’, where he created monumental books that will be remembered in the history of the publishing culture movement, such as ‘Dawn of Labor’, ‘Beyond Death, Beyond the Darkness of the Age’, and ‘Korean People’s History’. From the late 1980s, he was active as a literary critic representing the ‘popular national literature theory’.

Around 1991, when the fervent reform movement of the 1980s was fading away, he too entered graduate school and entered a life of “internal exile” amidst “disillusionment” and “contemplation.” However, starting in 1998, he began writing criticism again, and as the editor-in-chief of the quarterly current affairs and culture magazine “Hwanghae Culture,” a university professor, and a columnist for various media outlets, he has consistently participated in the field of change or testified to it while thoughtfully observing Korean society.

In this way, from the sentencing for violating the Anti-Communism Act and Martial Law in 1981 to the acquittal in 2020, or more precisely, from 1977 to 2024, a young man who dreamed of revolution for the people became an older citizen who, along with other citizens, dreams of fundamental change and strives to put it into practice in the midst of his ordinary daily life.

And through this book, which surveys these 50 years in language that is intense yet delicate, sharp yet humorous, readers can gain a vivid understanding and valuable insight into the context of what has happened in Korean society, what we have done and failed to do, and what we must do from now on.

A Radical Reconstruction of the Memoir Genre

Between Two Martial Laws radically deconstructs and reconstructs the memoir genre.

This book combines autobiographical and socio-historical accounts while simultaneously attempting a radical self-analysis.

The author gave this writing practice the name 'Memoir' instead of 'Memoir', which is considered a personal writing about one's entire life.

The author writes:

“I have never been just an individual in all these years.

It is precisely when we feel most isolated and disconnected that we are in fact most deeply involved with the world.

Looking back on the times when I was so terribly intertwined with the world is like digging into the deep side of the world and myself to uncover its logic.

Just looking back is not enough.

“So, I would like to go a step further from the term ‘memoir’ (回顧錄), which means looking back on one’s life, to ‘retrospection’ (回省錄), which means looking back critically on one’s life.” (pp. 9-10)

This is in line with the autodescription tradition, a methodology in anthropology and sociology, or Bourdieu's 'social analysis of the self,' Annie Ernaux's autofiction, and Didier Heribon's 'sociological self-reflection.'

The technique of “overlapping historical context over memories and images” (p. 114) is not limited to “The Murim Incident” but encompasses the entire book, showing how the social and historical constitute the personal.

The author meticulously captures the process by which personal experiences and public history intersect and interpenetrate, and goes beyond honest self-confession and memoir to conduct a meticulous self-criticism that thoroughly dissects existing works, thoughts, and even specific emotions that have been preoccupied with the past.

We confront existential, ethical, and political questions with utmost honesty, boldly approaching their most fundamental core, and pushing through to the very end, never stopping to think.

The courage to present even one's own inner self as a text or historical source for later generations to refer to and critique is one of the most radical points in this book.

In particular, this book devotes a significant portion of its text to delving into the origins of this ethical and political existence that the author has maintained throughout his life's trajectory: the university and student movements of the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the turbulent times of the popular, national, and democratic transformation movements of the late 1980s and early 1990s, by taking readers into the turbulent times, and delving into the archetype of the attitude toward life that he still maintains.

Although he sometimes looks back on his past life with a cool and critical eye, he finds that the barbarism and injustice of society, including state violence, are everywhere, and there is a “romantic impulse to go beyond ‘this state of affairs’” (p. 90), a very strong desire and energy, extreme sadness, anger, and guilt, and a pendulum movement between disillusionment and hope that continues thereafter.

And that is precisely the core emotion shared by the author and “the ‘warriors of the past’ in their 50s and 60s who lived in a similar era” (p. 16), or more precisely, the revolutionary activists and leftists of the past 40 to 50 years, and the collective inner landscape captured by the author.

This book, written with the author's pure sincerity and sharp intellect, vividly recreates the inner landscape of a person who has struggled through the democratization and post-democratization eras of the past half-century. At the same time, it knocks on the frozen sensibilities of those living in this era, awakening the "romantic impulse" toward the world that has been crouching within their hearts. It will also evoke a deep sympathy for a reflective attitude toward the world and humanity, and the ethics of critical writing.

I will tell you the long story of how I came to stand in the position of a citizen.”

Between martial law in 1979 and 2024, or 40 years after the Murim Incident

Critic Kim Myeong-in, who was imprisoned as one of the masterminds of the 'Murim Incident' in 1980 and was found not guilty in a retrial in 2020, 40 years later, published 'Hoeseongnok' (回省錄) 'Between Two Martial Laws', which conveys "the experiences and thoughts of an old citizen who has wrestled with the past 45 years" (p. 41), as "a record of reflection from a past generation to today's young generation and a proposal of empathy and solidarity extended with a shameful hand" (p. 16).

The 'Murim Incident' was an anti-government protest that occurred on the campus of Seoul National University on December 11, 1980.

This became a "public security incident" under the military regime, with many people involved being sentenced to prison or forcibly conscripted, and it caused great repercussions in the history of the student movement in the 1980s and in modern Korean history.

This book began with the intention of compiling a report with historical value on the "Murim Incident" at the request of attorney Lee Myeong-chun, who was the defense attorney during the retrial process. However, it took on its current format following the author's suggestion to expand it to "record in detail the entire story of the student movement incident called the Moorim Incident that took place in 1980, but reinterpret the changes in Korean society over the 40 years leading up to its official evaluation changing from a leftist communist crime to a legitimate act of civil resistance, within the context of the twists and turns of one man's life" (p. 13).

Meanwhile, while writing this book, the author constantly felt that “the 40 years of his life after coming of age were a dark landscape colored entirely with ‘romantic melancholy,’” but in December 2024, while he was in the final stages of work, he experienced martial law for the first time in 45 years.

“On October 26, 1979, when I was in my early twenties, I experienced the martial law declared with the assassination of Park Chung-hee, and the military rebellion by Chun Doo-hwan and his group on December 12 of that year. In the winter of 2024, when I was in my late sixties, I was caught up in the whirlpool of another martial law.

Like a tightrope walker straddling a rope between two poles, I spent my entire adult life precariously crossing these two martial laws.

However, the long-term depression that began with the martial law I experienced in my early twenties surprisingly disappeared as I experienced this comical martial law in my later years and the amazing struggle of young citizens against it.” (p. 15) And the title of this book became ‘Between Two Martial Laws.’

The author continues:

“The new title may contain some melancholy, but through it, I have finally been able to positively accept my life, which has been tossed and turned like waves by the dynamics of modern Korean history, which does not easily allow for either pessimism or optimism.”

A dazzling combination of autobiographical and socio-historical records

In 『Between Two Martial Laws』, ‘individual life’ and ‘modern Korean history’ cannot be separated, and ‘autobiographical records’ and ‘social historical records’ are tightly intertwined.

Therefore, reading this book means reading the 'history' engraved in the life of an individual who has thought most intensely about Korean society.

The author wrote:

“From now on, I will tell you the long story of how a self-proclaimed revolutionary came to stand as a citizen.

This long story contains the details of what happened to me, to Korean society, and to the world during that long period of time, what I thought, what I did, and what I failed to do while going through those things.

(…) However, I intend to tell this story with the hope that it will be both an autobiographical account of one individual and a social historical record that will allow us to look into how Korean society has changed over the past 45 years.” (p. 41)

Since the late 1970s, which is also the author's entire adult life, he has been actively involved in key moments in modern Korean history and critically reflecting on their impact on daily life and society.

In December 1980, Kim Myeong-in, a senior in the Department of Korean Language and Literature at Seoul National University who wrote the document titled “Anti-Fascist Student Struggle Declaration,” was taken away by detectives on the grounds that he was the instigator of the “Murim Incident.” He was subjected to illegal interrogation involving inhumane torture and imprisoned for two years and seven months as a “leftist” for violating the Anti-Communist Act and Martial Law.

Afterwards, he worked as an employee at a small trading agency and then as editor-in-chief of the humanities and social sciences publishing company ‘Pulbit’, where he created monumental books that will be remembered in the history of the publishing culture movement, such as ‘Dawn of Labor’, ‘Beyond Death, Beyond the Darkness of the Age’, and ‘Korean People’s History’. From the late 1980s, he was active as a literary critic representing the ‘popular national literature theory’.

Around 1991, when the fervent reform movement of the 1980s was fading away, he too entered graduate school and entered a life of “internal exile” amidst “disillusionment” and “contemplation.” However, starting in 1998, he began writing criticism again, and as the editor-in-chief of the quarterly current affairs and culture magazine “Hwanghae Culture,” a university professor, and a columnist for various media outlets, he has consistently participated in the field of change or testified to it while thoughtfully observing Korean society.

In this way, from the sentencing for violating the Anti-Communism Act and Martial Law in 1981 to the acquittal in 2020, or more precisely, from 1977 to 2024, a young man who dreamed of revolution for the people became an older citizen who, along with other citizens, dreams of fundamental change and strives to put it into practice in the midst of his ordinary daily life.

And through this book, which surveys these 50 years in language that is intense yet delicate, sharp yet humorous, readers can gain a vivid understanding and valuable insight into the context of what has happened in Korean society, what we have done and failed to do, and what we must do from now on.

A Radical Reconstruction of the Memoir Genre

Between Two Martial Laws radically deconstructs and reconstructs the memoir genre.

This book combines autobiographical and socio-historical accounts while simultaneously attempting a radical self-analysis.

The author gave this writing practice the name 'Memoir' instead of 'Memoir', which is considered a personal writing about one's entire life.

The author writes:

“I have never been just an individual in all these years.

It is precisely when we feel most isolated and disconnected that we are in fact most deeply involved with the world.

Looking back on the times when I was so terribly intertwined with the world is like digging into the deep side of the world and myself to uncover its logic.

Just looking back is not enough.

“So, I would like to go a step further from the term ‘memoir’ (回顧錄), which means looking back on one’s life, to ‘retrospection’ (回省錄), which means looking back critically on one’s life.” (pp. 9-10)

This is in line with the autodescription tradition, a methodology in anthropology and sociology, or Bourdieu's 'social analysis of the self,' Annie Ernaux's autofiction, and Didier Heribon's 'sociological self-reflection.'

The technique of “overlapping historical context over memories and images” (p. 114) is not limited to “The Murim Incident” but encompasses the entire book, showing how the social and historical constitute the personal.

The author meticulously captures the process by which personal experiences and public history intersect and interpenetrate, and goes beyond honest self-confession and memoir to conduct a meticulous self-criticism that thoroughly dissects existing works, thoughts, and even specific emotions that have been preoccupied with the past.

We confront existential, ethical, and political questions with utmost honesty, boldly approaching their most fundamental core, and pushing through to the very end, never stopping to think.

The courage to present even one's own inner self as a text or historical source for later generations to refer to and critique is one of the most radical points in this book.

In particular, this book devotes a significant portion of its text to delving into the origins of this ethical and political existence that the author has maintained throughout his life's trajectory: the university and student movements of the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the turbulent times of the popular, national, and democratic transformation movements of the late 1980s and early 1990s, by taking readers into the turbulent times, and delving into the archetype of the attitude toward life that he still maintains.

Although he sometimes looks back on his past life with a cool and critical eye, he finds that the barbarism and injustice of society, including state violence, are everywhere, and there is a “romantic impulse to go beyond ‘this state of affairs’” (p. 90), a very strong desire and energy, extreme sadness, anger, and guilt, and a pendulum movement between disillusionment and hope that continues thereafter.

And that is precisely the core emotion shared by the author and “the ‘warriors of the past’ in their 50s and 60s who lived in a similar era” (p. 16), or more precisely, the revolutionary activists and leftists of the past 40 to 50 years, and the collective inner landscape captured by the author.

This book, written with the author's pure sincerity and sharp intellect, vividly recreates the inner landscape of a person who has struggled through the democratization and post-democratization eras of the past half-century. At the same time, it knocks on the frozen sensibilities of those living in this era, awakening the "romantic impulse" toward the world that has been crouching within their hearts. It will also evoke a deep sympathy for a reflective attitude toward the world and humanity, and the ethics of critical writing.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 27, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 512 pages | 554g | 128*200*25mm

- ISBN13: 9791194442288

- ISBN10: 1194442285

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)