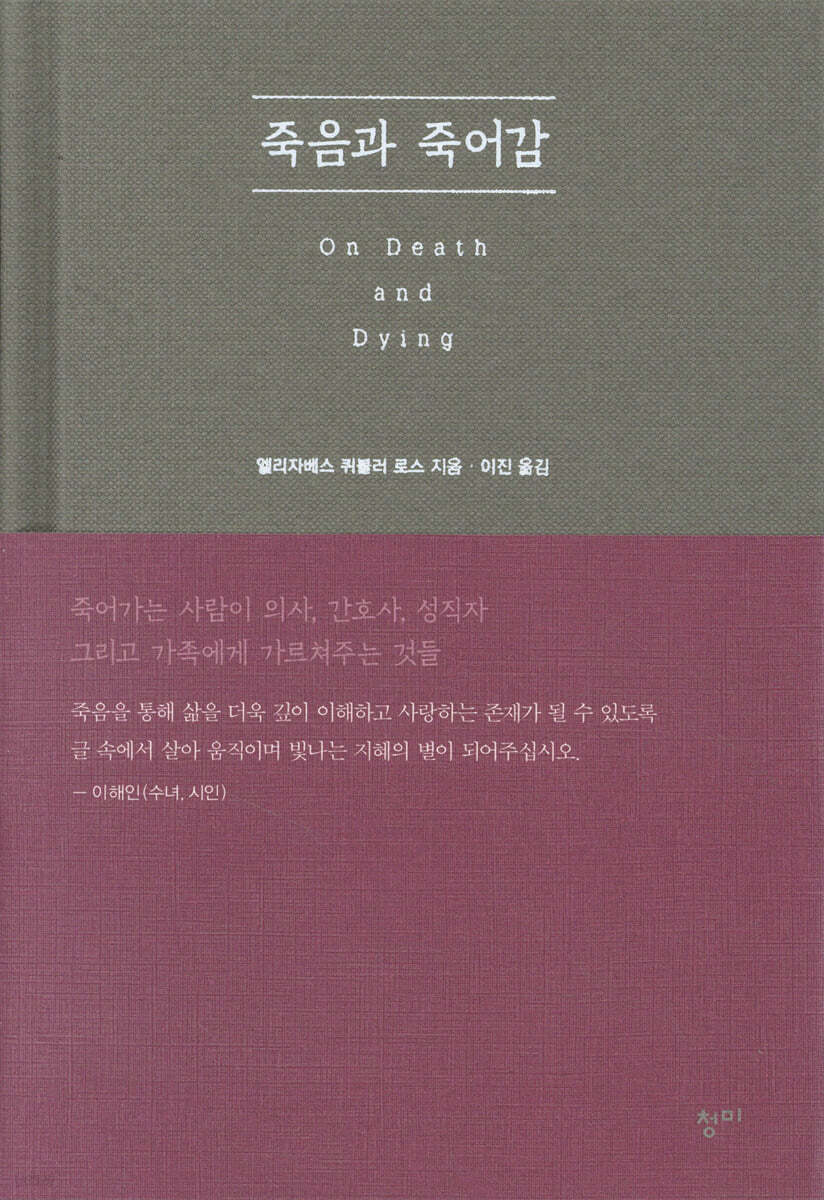

Death and Dying

|

Description

Book Introduction

Fifty years have passed since the publication of Death and Dying in 1969.

With the implementation of the 'Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment', Korea began to think about death with dignity.

At the time of the publication of "Death and Dying," the United States, having endured the Great Depression, World War II, and the Korean War, was permeated with an optimistic attitude that almost overshadowed pessimism. The tremendous advancements in medicine and science, such as the development of antibiotics, which drastically reduced the death toll, made it seem as if even death could be conquered.

However, as science advanced, the medical community learned techniques to extend life, but there was no discussion or training on the definition of life, and many people still did not experience a humane death that was a true extension of life.

“Death and Dying” created a social stir.

Death and Dying ignited a shift in consciousness and completely transformed clinical practice in just a few years.

Dying patients were no longer hidden, and the effectiveness of quantitative and qualitative research on nursing care for the critically ill and the terminally ill contributed to accelerated advances in psychology, psychiatry, geriatrics, clinical ethics, and anthropology.

The cultural impact of "On Death and Dying" was so profound that it forced Americans to understand disease and dying for the first time.

In Korea, where the 'Act on End-of-Life Decisions' will be implemented in 2018, I hope that Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's immortal masterpiece, 'On Death and Dying,' will spark a cultural movement to help death and dying find their proper place in our lives.

With the implementation of the 'Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment', Korea began to think about death with dignity.

At the time of the publication of "Death and Dying," the United States, having endured the Great Depression, World War II, and the Korean War, was permeated with an optimistic attitude that almost overshadowed pessimism. The tremendous advancements in medicine and science, such as the development of antibiotics, which drastically reduced the death toll, made it seem as if even death could be conquered.

However, as science advanced, the medical community learned techniques to extend life, but there was no discussion or training on the definition of life, and many people still did not experience a humane death that was a true extension of life.

“Death and Dying” created a social stir.

Death and Dying ignited a shift in consciousness and completely transformed clinical practice in just a few years.

Dying patients were no longer hidden, and the effectiveness of quantitative and qualitative research on nursing care for the critically ill and the terminally ill contributed to accelerated advances in psychology, psychiatry, geriatrics, clinical ethics, and anthropology.

The cultural impact of "On Death and Dying" was so profound that it forced Americans to understand disease and dying for the first time.

In Korea, where the 'Act on End-of-Life Decisions' will be implemented in 2018, I hope that Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's immortal masterpiece, 'On Death and Dying,' will spark a cultural movement to help death and dying find their proper place in our lives.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

tribute

A note on the publication of the commemorative edition

introduction

Chapter 1 - Fear of Death

Chapter 2 - Attitudes Toward Death and Dying

Chapter 3 - Stage 1: Denial and Isolation

Chapter 4 - Stage 2: Anger

Chapter 5 - Stage 3: Negotiation

Chapter 6 - Stage 4: Depression

Chapter 7 - Stage 5: Acceptance

Chapter 8 - Hope

Chapter 9 - The Patient's Family

Chapter 10 - Interviews with Terminally Ill Patients

Chapter 11 - Responses to the Seminar on Death and Dying

Chapter 12 - Treatment with Terminally Ill Patients

References

Reading Group Guide

In-Depth Discussion Guide

Translator's Note

tribute

A note on the publication of the commemorative edition

introduction

Chapter 1 - Fear of Death

Chapter 2 - Attitudes Toward Death and Dying

Chapter 3 - Stage 1: Denial and Isolation

Chapter 4 - Stage 2: Anger

Chapter 5 - Stage 3: Negotiation

Chapter 6 - Stage 4: Depression

Chapter 7 - Stage 5: Acceptance

Chapter 8 - Hope

Chapter 9 - The Patient's Family

Chapter 10 - Interviews with Terminally Ill Patients

Chapter 11 - Responses to the Seminar on Death and Dying

Chapter 12 - Treatment with Terminally Ill Patients

References

Reading Group Guide

In-Depth Discussion Guide

Translator's Note

Into the book

We believe that our great intellectual freedom, our knowledge of humanity and science, has provided us and our families with the means and methods to better prepare ourselves for this inevitable fate.

However, the era in which a person could die with dignity at home has ended.

As science advances, it seems that humans become more and more afraid and in denial of the truth of death.

How did it come to this? --- p.39

Here we cannot help but ask this question:

Are we moving towards a more humane or dehumanizing approach? This book is not intended to be judgmental, but whatever the answer, patients are clearly suffering more than ever.

Even if not physically, emotionally.

Patients' needs have not changed over the centuries.

It's just that our ability to satisfy their needs has changed.

--- p.43

If we don't turn away in fear the moment we see a helpless and suffering human being, we can join forces and help the patient utilize whatever abilities he or she may have left.

What I'm trying to say is that we can help patients die by helping them truly live, rather than by keeping them helpless and living in an inhumane way.

--- p.61

I believe that everyone should habitually think about death and dying before actually facing it.

If we don't, a cancer diagnosis in our family will be a stark reminder of our own mortality.

So, if you can think about your own death and dying during your illness, that time can be a blessing, whether you actually encounter death or your life is extended.

--- p.73

I believe the question, “Should I tell the patient?” should be replaced with, “How do I share what I know with the patient?”

--- p.83

Patients who are respected and understood, who are given attention and time, will soon lower their voices and stop making angry demands.

They will know that they are valuable human beings, that they are cared for, and that they are allowed to perform at the highest level their circumstances allow.

--- p.108

Just as we can talk about babies with someone who is expecting, more people should be able to talk about death and dying as an inherent part of our lives.

--- p.246

I think it's cruel to force one family member to always be the patient's caregiver.

Just as there is a time to inhale and a time to exhale, people need time to 'recharge their batteries' outside the hospital room and enjoy a normal life from time to time.

You cannot provide effective nursing care if you are always conscious of the patient.

--- p.271

At this point, I would like to reiterate my belief that every patient has the right to die peacefully and with dignity.

We should not use patients to satisfy our own needs when their needs conflict with ours.

--- p.295

We talk about death—a socially repressed topic—in an honest and simple way, open to a wide range of discussion, tolerate complete denial when necessary, and openly discuss our patients' fears and concerns if they so choose.

The fact that 'we' do not take a negative attitude, that we are willing to use the words death and dying, is probably the most welcome form of communication for many patients.

--- p.418

When I watch the peaceful death of a human being, I think of a falling star.

Among the millions of stars twinkling in the vast sky, one shines brightly for a brief moment and then disappears forever into the endless darkness.

Being a therapist at the side of a dying patient reminds us of the uniqueness of each individual in this vast sea of humanity.

It reminds us of the finiteness of human beings, of the finiteness of our lives.

Few of us live past the age of seventy, yet in that short time, most of us live unique lives and weave ourselves into the fabric of human history.

However, the era in which a person could die with dignity at home has ended.

As science advances, it seems that humans become more and more afraid and in denial of the truth of death.

How did it come to this? --- p.39

Here we cannot help but ask this question:

Are we moving towards a more humane or dehumanizing approach? This book is not intended to be judgmental, but whatever the answer, patients are clearly suffering more than ever.

Even if not physically, emotionally.

Patients' needs have not changed over the centuries.

It's just that our ability to satisfy their needs has changed.

--- p.43

If we don't turn away in fear the moment we see a helpless and suffering human being, we can join forces and help the patient utilize whatever abilities he or she may have left.

What I'm trying to say is that we can help patients die by helping them truly live, rather than by keeping them helpless and living in an inhumane way.

--- p.61

I believe that everyone should habitually think about death and dying before actually facing it.

If we don't, a cancer diagnosis in our family will be a stark reminder of our own mortality.

So, if you can think about your own death and dying during your illness, that time can be a blessing, whether you actually encounter death or your life is extended.

--- p.73

I believe the question, “Should I tell the patient?” should be replaced with, “How do I share what I know with the patient?”

--- p.83

Patients who are respected and understood, who are given attention and time, will soon lower their voices and stop making angry demands.

They will know that they are valuable human beings, that they are cared for, and that they are allowed to perform at the highest level their circumstances allow.

--- p.108

Just as we can talk about babies with someone who is expecting, more people should be able to talk about death and dying as an inherent part of our lives.

--- p.246

I think it's cruel to force one family member to always be the patient's caregiver.

Just as there is a time to inhale and a time to exhale, people need time to 'recharge their batteries' outside the hospital room and enjoy a normal life from time to time.

You cannot provide effective nursing care if you are always conscious of the patient.

--- p.271

At this point, I would like to reiterate my belief that every patient has the right to die peacefully and with dignity.

We should not use patients to satisfy our own needs when their needs conflict with ours.

--- p.295

We talk about death—a socially repressed topic—in an honest and simple way, open to a wide range of discussion, tolerate complete denial when necessary, and openly discuss our patients' fears and concerns if they so choose.

The fact that 'we' do not take a negative attitude, that we are willing to use the words death and dying, is probably the most welcome form of communication for many patients.

--- p.418

When I watch the peaceful death of a human being, I think of a falling star.

Among the millions of stars twinkling in the vast sky, one shines brightly for a brief moment and then disappears forever into the endless darkness.

Being a therapist at the side of a dying patient reminds us of the uniqueness of each individual in this vast sea of humanity.

It reminds us of the finiteness of human beings, of the finiteness of our lives.

Few of us live past the age of seventy, yet in that short time, most of us live unique lives and weave ourselves into the fabric of human history.

--- p.439

Publisher's Review

After reading 『Death and Dying』, a book about death that reveals the meaning of life,

- To Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

From the recommendation of Lee Hae-in (nun, poet)

I cannot help but recommend 『Death and Dying』 as a must-read for everyone at least once.

This is especially true because this book is a book about death, but it also talks about life.

Although you are far away, be a living, shining star of wisdom in your writings, so that through death we may become beings who understand and love life more deeply.

A student nun who studied 『Death and Dying』 at the Benedictine Convent

A classic study of thanatology that first introduced the 'Five Stages of Death'!

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, author of "Life Lessons," a masterpiece

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a pioneer of the hospice movement and a representative psychiatrist of the 20th century, first proposed the famous 'five stages of death' of denial, isolation, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance in her interdisciplinary seminar study on death, life, and transition in 'Death and Dying'.

With Death and Dying, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross gave people a voice to confront the end of life and added the question of "how to die" to the list of cultural revolutions in the fields of environment, social rights, and health care.

Everything changed after that.

It's a good thing for all of us.

-?Ira?Biok (Doctor of Medicine,?Professor)

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross's "Death and Dying"

This is a study that has been ranked as a classic.

-?Slavoj Zizek (philosopher, professor)

A profound lesson about life

-Life Magazine

If we had to read only one book before we die,

That would be this book.

- Lee Jin (translator)

? Publisher's Review

Fifty years have passed since the publication of Death and Dying in 1969.

With the implementation of the 'Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment', Korea began to think about death with dignity.

At the time of the publication of "Death and Dying," the United States, having endured the Great Depression, World War II, and the Korean War, was permeated with an optimistic attitude that almost overshadowed pessimism. The tremendous advancements in medicine and science, such as the development of antibiotics, which drastically reduced the death toll, made it seem as if even death could be conquered.

However, as science advanced, the medical community learned techniques to extend life, but there was no discussion or training on the definition of life, and many people still did not experience a humane death that was a true extension of life.

“Death and Dying” created a social stir.

Death and Dying ignited a shift in consciousness and completely transformed clinical practice in just a few years.

Dying patients were no longer hidden, and the effectiveness of quantitative and qualitative research on nursing care for the critically ill and the terminally ill contributed to accelerated advances in psychology, psychiatry, geriatrics, clinical ethics, and anthropology.

The cultural impact of "On Death and Dying" was so profound that it forced Americans to understand disease and dying for the first time.

In Korea, where the 'Act on End-of-Life Decisions' will be implemented in 2018, I hope that Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's immortal masterpiece, 'On Death and Dying,' will spark a cultural movement to help death and dying find their proper place in our lives.

By putting death on the stage, we are reminded of the finiteness of human life,

By not losing the uniqueness of each individual human being, we have laid the foundation for completing the epic of life.

Death, representing the fragility of life, is the greatest fear humans have, but Elisabeth Kübler-Ross showed the courage of her time by personally meeting dying patients and exploring the issues they face in their final hours.

I did not explain my patients using Freudian or Jungian formulas.

In an era when people whispered about illness, he brought the patient to the podium and made him a teacher to doctors and students, creating a psychological dynamic between the sick and the still healthy.

He demonstrated to the medical staff, medical students, and clergy, through their eyes and ears, the emotional states and adaptive mechanisms of how patients struggle to live and how they accept incurable diseases.

The five stages of death (denial and isolation - anger - bargaining - depression - acceptance) were first established through this process and have had a significant impact on human research.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross spoke to humanity, encouraging people to accept death as a part of life, understand life more deeply, and live their daily lives more fully.

We must return to being human as individual beings and learn to understand and face the tragic but inevitable event of death more rationally and fearlessly from the beginning.

More people need to be able to talk about death and dying as an inherent part of our lives.

Like the poem she quoted from Tagore's "Lost Birds": "As birth is a part of life, so is death / The step that rises is a step, and the step that lands is a step."

Although there is great intellectual freedom and knowledge of medicine and science is increasing day by day,

The era in which a person could die with dignity at home is over.

Only humans know that life will end one day, yet many people still end their lives in an inhumane death.

Many people want to end their lives in a familiar and loving environment, but many end up dying in hospitals.

Death in modern society has become lonelier, more mechanical, and more inhumane.

Sometimes it is even difficult to determine when a patient has actually died.

In our modern, highly civilized society, we are unable to face a peaceful death as a part of life.

"Is it possible that we are so afraid of death that we cling to machines instead of all the wisdom we possess? Is it possible that machines are closer to us than the pained face of a human being, a reminder of our weaknesses, our limitations, our failures, and even our own mortality?" I am uneasy at the fact that her question, posed 50 years ago, remains relevant today.

Death is an ominous and fearful event, and has always been and always will be an object of disgust.

If there is one thing that needs to change, it is the way we deal with and interact with death and dying.

We all need to seriously consider our own death, face the truth, and accept it so we can live each day as if it were our last, and end our lives more humanely.

'How to die' has emerged as an important issue.

The message of a mid-20th-century female doctor, “Death and Dying,” is still relevant to Korean readers today.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross brought the topics of illness and death, which had been confined to the realm of medicine and doctors, into the realm of life experience and the private realm of each individual.

It fundamentally restructured the relationship between patients and medical professionals and restored an individual's autonomy over death and dying.

How far we have come, and how far we still have to go, to achieve a truly human-centered life.

Even in this age of civilization, sick patients are still taking paths they never chose, paths we all must eventually take.

Even though we know our own finitude, the way we die is not predetermined, and can be for better or worse depending on our choices.

As Elisabeth Kübler-Ross herself has said when encountering dying people, everyone should habitually think about death and dying before they actually face it – because it is less frightening when it is far away than when it is right in front of them.

Because death is also a part of life.

“The most essential and important core of my research, which has been conducted for over 30 years, is

“It was about uncovering the meaning of life.”

- Elisabeth Kubler-Ross -

- To Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

From the recommendation of Lee Hae-in (nun, poet)

I cannot help but recommend 『Death and Dying』 as a must-read for everyone at least once.

This is especially true because this book is a book about death, but it also talks about life.

Although you are far away, be a living, shining star of wisdom in your writings, so that through death we may become beings who understand and love life more deeply.

A student nun who studied 『Death and Dying』 at the Benedictine Convent

A classic study of thanatology that first introduced the 'Five Stages of Death'!

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, author of "Life Lessons," a masterpiece

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a pioneer of the hospice movement and a representative psychiatrist of the 20th century, first proposed the famous 'five stages of death' of denial, isolation, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance in her interdisciplinary seminar study on death, life, and transition in 'Death and Dying'.

With Death and Dying, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross gave people a voice to confront the end of life and added the question of "how to die" to the list of cultural revolutions in the fields of environment, social rights, and health care.

Everything changed after that.

It's a good thing for all of us.

-?Ira?Biok (Doctor of Medicine,?Professor)

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross's "Death and Dying"

This is a study that has been ranked as a classic.

-?Slavoj Zizek (philosopher, professor)

A profound lesson about life

-Life Magazine

If we had to read only one book before we die,

That would be this book.

- Lee Jin (translator)

? Publisher's Review

Fifty years have passed since the publication of Death and Dying in 1969.

With the implementation of the 'Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment', Korea began to think about death with dignity.

At the time of the publication of "Death and Dying," the United States, having endured the Great Depression, World War II, and the Korean War, was permeated with an optimistic attitude that almost overshadowed pessimism. The tremendous advancements in medicine and science, such as the development of antibiotics, which drastically reduced the death toll, made it seem as if even death could be conquered.

However, as science advanced, the medical community learned techniques to extend life, but there was no discussion or training on the definition of life, and many people still did not experience a humane death that was a true extension of life.

“Death and Dying” created a social stir.

Death and Dying ignited a shift in consciousness and completely transformed clinical practice in just a few years.

Dying patients were no longer hidden, and the effectiveness of quantitative and qualitative research on nursing care for the critically ill and the terminally ill contributed to accelerated advances in psychology, psychiatry, geriatrics, clinical ethics, and anthropology.

The cultural impact of "On Death and Dying" was so profound that it forced Americans to understand disease and dying for the first time.

In Korea, where the 'Act on End-of-Life Decisions' will be implemented in 2018, I hope that Elisabeth Kübler-Ross's immortal masterpiece, 'On Death and Dying,' will spark a cultural movement to help death and dying find their proper place in our lives.

By putting death on the stage, we are reminded of the finiteness of human life,

By not losing the uniqueness of each individual human being, we have laid the foundation for completing the epic of life.

Death, representing the fragility of life, is the greatest fear humans have, but Elisabeth Kübler-Ross showed the courage of her time by personally meeting dying patients and exploring the issues they face in their final hours.

I did not explain my patients using Freudian or Jungian formulas.

In an era when people whispered about illness, he brought the patient to the podium and made him a teacher to doctors and students, creating a psychological dynamic between the sick and the still healthy.

He demonstrated to the medical staff, medical students, and clergy, through their eyes and ears, the emotional states and adaptive mechanisms of how patients struggle to live and how they accept incurable diseases.

The five stages of death (denial and isolation - anger - bargaining - depression - acceptance) were first established through this process and have had a significant impact on human research.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross spoke to humanity, encouraging people to accept death as a part of life, understand life more deeply, and live their daily lives more fully.

We must return to being human as individual beings and learn to understand and face the tragic but inevitable event of death more rationally and fearlessly from the beginning.

More people need to be able to talk about death and dying as an inherent part of our lives.

Like the poem she quoted from Tagore's "Lost Birds": "As birth is a part of life, so is death / The step that rises is a step, and the step that lands is a step."

Although there is great intellectual freedom and knowledge of medicine and science is increasing day by day,

The era in which a person could die with dignity at home is over.

Only humans know that life will end one day, yet many people still end their lives in an inhumane death.

Many people want to end their lives in a familiar and loving environment, but many end up dying in hospitals.

Death in modern society has become lonelier, more mechanical, and more inhumane.

Sometimes it is even difficult to determine when a patient has actually died.

In our modern, highly civilized society, we are unable to face a peaceful death as a part of life.

"Is it possible that we are so afraid of death that we cling to machines instead of all the wisdom we possess? Is it possible that machines are closer to us than the pained face of a human being, a reminder of our weaknesses, our limitations, our failures, and even our own mortality?" I am uneasy at the fact that her question, posed 50 years ago, remains relevant today.

Death is an ominous and fearful event, and has always been and always will be an object of disgust.

If there is one thing that needs to change, it is the way we deal with and interact with death and dying.

We all need to seriously consider our own death, face the truth, and accept it so we can live each day as if it were our last, and end our lives more humanely.

'How to die' has emerged as an important issue.

The message of a mid-20th-century female doctor, “Death and Dying,” is still relevant to Korean readers today.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross brought the topics of illness and death, which had been confined to the realm of medicine and doctors, into the realm of life experience and the private realm of each individual.

It fundamentally restructured the relationship between patients and medical professionals and restored an individual's autonomy over death and dying.

How far we have come, and how far we still have to go, to achieve a truly human-centered life.

Even in this age of civilization, sick patients are still taking paths they never chose, paths we all must eventually take.

Even though we know our own finitude, the way we die is not predetermined, and can be for better or worse depending on our choices.

As Elisabeth Kübler-Ross herself has said when encountering dying people, everyone should habitually think about death and dying before they actually face it – because it is less frightening when it is far away than when it is right in front of them.

Because death is also a part of life.

“The most essential and important core of my research, which has been conducted for over 30 years, is

“It was about uncovering the meaning of life.”

- Elisabeth Kubler-Ross -

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: January 29, 2018

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 468 pages | 546g | 128*188*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791195990467

- ISBN10: 1195990464

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)