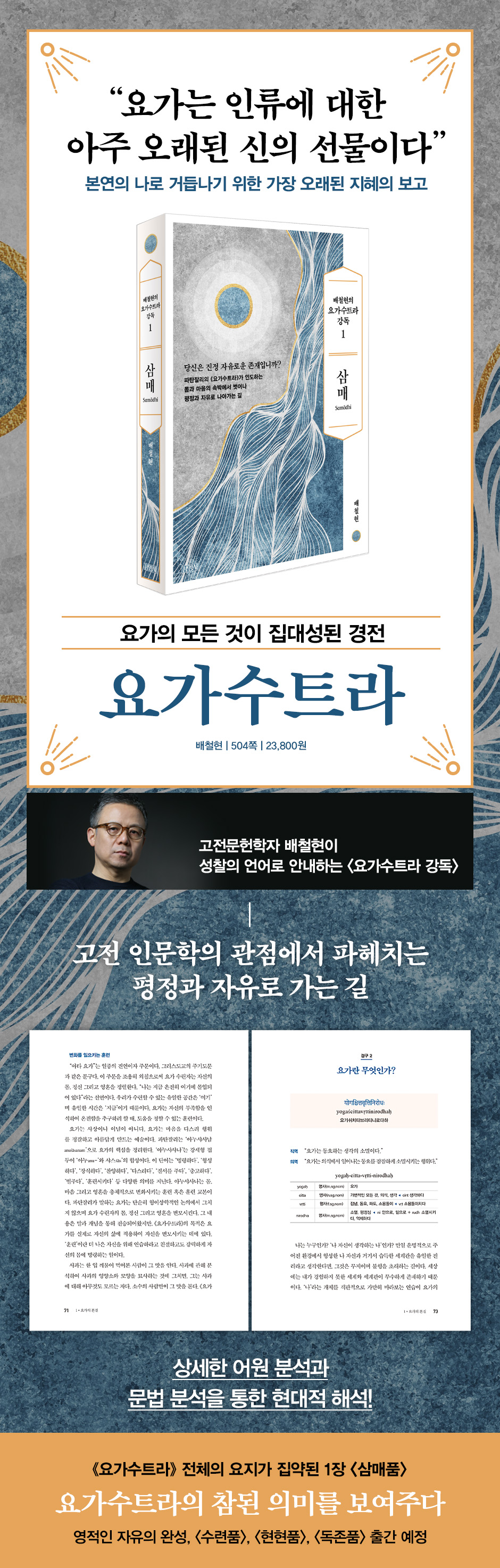

Bae Cheol-hyeon's Yoga Sutra Reading 1 Samadhi

|

Description

Book Introduction

The oldest treasure trove of wisdom for rebirth into a new self Classical philologist Bae Cheol-hyeon guides us through the language of reflection in 『Bae Cheol-hyeon's Yoga Sutra Reading 1 - Samadhi』 The Yoga Sutras are a scripture that systematically explains the essence of yoga, the oldest mental training method known to mankind. The Yoga Sutra consists of four chapters: “Samadhi,” “Practice,” “Manifestation,” and “Solomon,” and a total of 195 lines of sutras. Bae Cheol-hyeon, the only classical literature scholar in Korea, first introduces the interpretation and explanation of the 51 verses of Chapter 1, “Sammae-pum.” This book departs from existing commentaries on the Yoga Sutras, which focus solely on the perspective of Indian philosophy. It encompasses all of the humanities of the East and the West, including ancient mythology, religion, philosophy, psychology, and linguistics, as well as classics such as Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Dante's Divine Comedy, and shows us the path to freedom for the liberation of the human spirit through the Yoga Sutra. By providing a detailed introduction to the etymology and grammar of Sanskrit words written in Devanagari and Romanized, the script in which the Yoga Sutras were written, and by providing an in-depth explanation of the original Sanskrit text sentence by sentence, the author not only fully demonstrates his expertise as an expert in ancient languages such as Semitic, Indo-Iranian, Greek, and Latin, but also helps readers to correctly understand the original text. The 51 verses of the “Samadhi-Pum” contain the themes of the “Yoga Sutra” that will be developed in the future and the core concepts of yoga practice. Let's memorize the meaning of one verse a week or a day and train our body and mind. By breaking free from the obsessions that unconsciously control your thoughts, words, and actions, you will discover your true self and attain spiritual freedom. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

prolog

Part 1: What is Yoga?

1.

Yoga Defined: A Revolution of the Mind

2.

The Language of Yoga: Sanskrit

Part 2: What is the Yoga Sutra?

1.

The Birth of the Yoga Sutras

2.

The spread of the Yoga Sutra

3.

Patanjali, the compiler of the Yoga Sutras

Reading the Yoga Sutras, Part 3, Chapter on Samadhi

1.

The essence of yoga

Oral 1.

What is now?

Oral 2.

What is yoga?

Oral 3.

Who am I that looks at me?

Oral 4.

What is a pseudoscience?

2.

Types of Thought

Oral 5.

What is pollution?

Oral 6.

What are five things that stir your heart?

Oral 7.

What is righteousness?

Oral 8.

What is an illusion?

Oral 9.

What is a concept?

Oral 10.

What is sleep?

Oral 11.

What is memory?

3.

Practice and desire

Oral 12.

What are the two principles of extinction?

Oral 13.

What is effort?

Oral 14.

What is persistence?

Oral 15.

What is selfishness?

Oral 16.

What is aloofness?

4.

Two types of conditioned samadhi: conditioned samadhi and non-conditioned samadhi

Oral 17.

What is the paid samadhi?

Oral 18.

What is the Samadhi of No-Sang?

Oral 19.

What is creation?

Oral 20.

What is acquisition?

Oral 21.

What is earnestness?

Oral 22.

What are the three stages of the samadhi?

5.

Devotion to God

Oral 23.

What is dedication?

Oral 24.

Who is God?

Oral 25.

What is a battery?

Oral 26.

Who is a guru?

Oral 27.

What is a word?

Oral 28.

What is the purpose of reciting Om?

Oral 29.

What is an internal organ?

6.

Overcoming interruptions and distractions

Oral 30.

What hinders yoga practice?

Oral 31.

What are the symptoms created by yoga saboteurs?

Oral 32.

What is the one principle of practicing yoga?

7.

composure

Oral 33.

Do you have these four minds?

Oral 34.

Do you pause before exhaling?

Oral 35.

Do you look at the object indifferently?

Oral 36.

Is there no sadness in your heart?

Oral 37.

Are your thoughts free?

Oral 38.

Do you sleep deeply?

Oral 39.

What are your hobbies?

Oral 40.

Do you keep your composure in everything?

8.

Characteristics and types of Yujongsammae

Oral 41.

Do you observe yourself observing?

Oral 42.

Do you discern the object as it is?

Oral 43.

Do you get the gist of the subject?

Oral 44.

Can you perceive what is invisible to the eyes?

Oral 45.

Can you see that there is no sign?

Oral 46.

Can you observe the world created by seeds?

Oral 47.

Do you see things clearly?

Oral 48.

Do you see through things?

Oral 49.

Do you see the specialness of the object?

Oral 50.

Do you have a new mindset?

9.

Characteristics of the Samadhi of Nojong

Oral 51.

Have you entered the very first state?

Epilogue

Appendix: Yoga Sutras, Samadhi Chapter, Sanskrit-Korean Dictionary

Search

Part 1: What is Yoga?

1.

Yoga Defined: A Revolution of the Mind

2.

The Language of Yoga: Sanskrit

Part 2: What is the Yoga Sutra?

1.

The Birth of the Yoga Sutras

2.

The spread of the Yoga Sutra

3.

Patanjali, the compiler of the Yoga Sutras

Reading the Yoga Sutras, Part 3, Chapter on Samadhi

1.

The essence of yoga

Oral 1.

What is now?

Oral 2.

What is yoga?

Oral 3.

Who am I that looks at me?

Oral 4.

What is a pseudoscience?

2.

Types of Thought

Oral 5.

What is pollution?

Oral 6.

What are five things that stir your heart?

Oral 7.

What is righteousness?

Oral 8.

What is an illusion?

Oral 9.

What is a concept?

Oral 10.

What is sleep?

Oral 11.

What is memory?

3.

Practice and desire

Oral 12.

What are the two principles of extinction?

Oral 13.

What is effort?

Oral 14.

What is persistence?

Oral 15.

What is selfishness?

Oral 16.

What is aloofness?

4.

Two types of conditioned samadhi: conditioned samadhi and non-conditioned samadhi

Oral 17.

What is the paid samadhi?

Oral 18.

What is the Samadhi of No-Sang?

Oral 19.

What is creation?

Oral 20.

What is acquisition?

Oral 21.

What is earnestness?

Oral 22.

What are the three stages of the samadhi?

5.

Devotion to God

Oral 23.

What is dedication?

Oral 24.

Who is God?

Oral 25.

What is a battery?

Oral 26.

Who is a guru?

Oral 27.

What is a word?

Oral 28.

What is the purpose of reciting Om?

Oral 29.

What is an internal organ?

6.

Overcoming interruptions and distractions

Oral 30.

What hinders yoga practice?

Oral 31.

What are the symptoms created by yoga saboteurs?

Oral 32.

What is the one principle of practicing yoga?

7.

composure

Oral 33.

Do you have these four minds?

Oral 34.

Do you pause before exhaling?

Oral 35.

Do you look at the object indifferently?

Oral 36.

Is there no sadness in your heart?

Oral 37.

Are your thoughts free?

Oral 38.

Do you sleep deeply?

Oral 39.

What are your hobbies?

Oral 40.

Do you keep your composure in everything?

8.

Characteristics and types of Yujongsammae

Oral 41.

Do you observe yourself observing?

Oral 42.

Do you discern the object as it is?

Oral 43.

Do you get the gist of the subject?

Oral 44.

Can you perceive what is invisible to the eyes?

Oral 45.

Can you see that there is no sign?

Oral 46.

Can you observe the world created by seeds?

Oral 47.

Do you see things clearly?

Oral 48.

Do you see through things?

Oral 49.

Do you see the specialness of the object?

Oral 50.

Do you have a new mindset?

9.

Characteristics of the Samadhi of Nojong

Oral 51.

Have you entered the very first state?

Epilogue

Appendix: Yoga Sutras, Samadhi Chapter, Sanskrit-Korean Dictionary

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

The word 'yoga' is dualistic.

Because they have conflicting meanings of ‘combination’ and ‘separation.’

The first meaning of yoga is 'union'.

'Yoga' comes from the Indo-European root *yuk-, which means 'rope' or 'rein' used by the Aryans around the 12th century BC to train their war animals.

The early Aryans trained wild horses by putting saddles and reins on them to turn them into fine horses.

The English word 'yoke', meaning 'yoke', also contains the meaning of yoga etymology.

Yoga is a systematic control and attack on the instinct and selfishness to act as one pleases.

Practitioners practice by reining in their minds to unite with their divine selves.

...

The second meaning of yoga is 'separation'.

'Separation' comes from a deeper analysis of the word 'yoga'.

Within the human heart, there exists a shining self that makes each person most true to themselves.

When man strives to find that self, that being, and finally brings it to fruition, he ascends from the state of the beast and transforms into a divine human being.

‘Separation’ is the process of setting aside distracting thoughts that prevent you from manifesting your divine self.

--- p.69

Patanjali, in his Yoga Sutras, asserts that the purpose of yoga is to cultivate one's true self.

He uses dra??u? instead of the terms atman or purusha.

This word is derived from the verb 'drisd??', which means 'to see', 'to learn', 'to understand'.

The 'act of seeing' that 'Dries' speaks of does not mean seeing things with the eyes, which are a physical organ.

Drashtuhu means 'one who sees with profound insight', 'an objective observer' or 'profound observation'.

The object of objective observation is special.

This is because the true self that exists within is the object of observation.

As mentioned earlier, the self-image here is not the appearance reflected in the mirror that can be seen with the eyes.

It is one's own unique individuality, a divine self that must be perfected through yoga practice.

Drashtuhu is a person who constantly witnesses the disturbances and phenomena occurring in his own mind.

--- pp.90~91

The ancient Hebrews created a finely marked ruler, essential for commerce.

Long reeds growing in the swamps of the Middle East were broken and notches were carved into their joints.

This person was called 'qaneh' in ancient Hebrew.

Kane, who sets standards that everyone agrees on, has become a force that makes community life run smoothly.

The ancient Greek word 'kanonκαν?ν' was borrowed from cane, which later became the Latin word 'kanoncan?n'.

After Christianity emerged, Christians selected only the books that revealed their identity from among the numerous books and named them 'Canon'.

After hundreds of years of fierce debate, they established the 66 books as the "Jeonggyeong (正經)", which they believed to be powerful scriptures that transcend time and change lives.

--- pp.43~44

The object of focus for yoga practitioners during their practice is Ishvara.

To him, God is a being to whom one can give one's all and is the ultimate object of one's wishes.

In 'pranidh?a', 'prani' is an affix that emphasizes the concept that follows, 'dadh?' is a verb meaning 'to place in the appropriate place in the order of the universe', and 'na' is a noun ending.

Therefore, pranidana is 'a devotion or wish that one pledges everything to.'

For a yoga practitioner, God is something that appears in the process of training to reach the highest level.

...

The word is associated with the early Buddhist term 'bodhisattva pranidh?na'.

Bodhisattva Pranidhana is a vow to renounce one's own final Nirvana in order to help others achieve liberation.

--- p.264

Meditation is not the act of sitting still and letting your mind wander or devising a survival of the fittest strategy to maximize your own interests.

Meditation is a sacred act of finding the reason for one's existence in this critical moment called today.

It is an act of finding the best for oneself within one's family, neighborhood, community, and nation.

Have I ever recited "Om," requiring patience and endurance, at a set time and place? Do I know the one reason I exist in this world? "Om" is the voice of conscience for practitioners who set out to find it.

--- p.306

What should we practice? Patanjali used the Sanskrit phrase "eka-tattva" to describe the object of practice.

The Sanskrit word 'eka', meaning 'one', is the original form before the dualistic structure created to understand the human world.

Two appear through one.

Plotinus, a Roman philosopher and contemporary of Patanjali, explains that all things have one origin and that reality flows from that one origin.

He defined the first principle, which is the highest reality and the foundation of the universe, as 'to hen', or 'the one', in ancient Greek.

...

The second word in this phrase, tattva, literally means 'itself'.

'It-in-itself' is the essence and phenomenon of a thing or person.

It is the beginning and the end of an event.

It is both the cause and the result of a phenomenon.

Tattva is also the abstract concept we commonly refer to as 'truth'.

--- pp.339~340

By discovering and igniting the inner light, yoga practitioners can achieve mental tranquility to enter samadhi.

This inner light is 'Tao' for Lao-tzu, 'goodness and beauty' for Plato, 'existence' for Aristotle, 'infinity' for Plotinus, 'inner heaven' for Jesus, and 'ein sof', meaning 'infinity' in Judaism.

Although the inner light has been expressed in various terms in each culture, it ultimately refers to a universal consciousness that resides within humans and hopes to be awakened through experience.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who developed the Indian technique of Transcendental Meditation, says that when humans naturally enter and remain within themselves, they can experience what Emerson called "wise silence."

In line 36 of the Samadhi chapter, Patanjali introduces the practice of 'inner light' as a way for yoga practitioners to eliminate distracting thoughts in order to enter the state of samadhi.

Because they have conflicting meanings of ‘combination’ and ‘separation.’

The first meaning of yoga is 'union'.

'Yoga' comes from the Indo-European root *yuk-, which means 'rope' or 'rein' used by the Aryans around the 12th century BC to train their war animals.

The early Aryans trained wild horses by putting saddles and reins on them to turn them into fine horses.

The English word 'yoke', meaning 'yoke', also contains the meaning of yoga etymology.

Yoga is a systematic control and attack on the instinct and selfishness to act as one pleases.

Practitioners practice by reining in their minds to unite with their divine selves.

...

The second meaning of yoga is 'separation'.

'Separation' comes from a deeper analysis of the word 'yoga'.

Within the human heart, there exists a shining self that makes each person most true to themselves.

When man strives to find that self, that being, and finally brings it to fruition, he ascends from the state of the beast and transforms into a divine human being.

‘Separation’ is the process of setting aside distracting thoughts that prevent you from manifesting your divine self.

--- p.69

Patanjali, in his Yoga Sutras, asserts that the purpose of yoga is to cultivate one's true self.

He uses dra??u? instead of the terms atman or purusha.

This word is derived from the verb 'drisd??', which means 'to see', 'to learn', 'to understand'.

The 'act of seeing' that 'Dries' speaks of does not mean seeing things with the eyes, which are a physical organ.

Drashtuhu means 'one who sees with profound insight', 'an objective observer' or 'profound observation'.

The object of objective observation is special.

This is because the true self that exists within is the object of observation.

As mentioned earlier, the self-image here is not the appearance reflected in the mirror that can be seen with the eyes.

It is one's own unique individuality, a divine self that must be perfected through yoga practice.

Drashtuhu is a person who constantly witnesses the disturbances and phenomena occurring in his own mind.

--- pp.90~91

The ancient Hebrews created a finely marked ruler, essential for commerce.

Long reeds growing in the swamps of the Middle East were broken and notches were carved into their joints.

This person was called 'qaneh' in ancient Hebrew.

Kane, who sets standards that everyone agrees on, has become a force that makes community life run smoothly.

The ancient Greek word 'kanonκαν?ν' was borrowed from cane, which later became the Latin word 'kanoncan?n'.

After Christianity emerged, Christians selected only the books that revealed their identity from among the numerous books and named them 'Canon'.

After hundreds of years of fierce debate, they established the 66 books as the "Jeonggyeong (正經)", which they believed to be powerful scriptures that transcend time and change lives.

--- pp.43~44

The object of focus for yoga practitioners during their practice is Ishvara.

To him, God is a being to whom one can give one's all and is the ultimate object of one's wishes.

In 'pranidh?a', 'prani' is an affix that emphasizes the concept that follows, 'dadh?' is a verb meaning 'to place in the appropriate place in the order of the universe', and 'na' is a noun ending.

Therefore, pranidana is 'a devotion or wish that one pledges everything to.'

For a yoga practitioner, God is something that appears in the process of training to reach the highest level.

...

The word is associated with the early Buddhist term 'bodhisattva pranidh?na'.

Bodhisattva Pranidhana is a vow to renounce one's own final Nirvana in order to help others achieve liberation.

--- p.264

Meditation is not the act of sitting still and letting your mind wander or devising a survival of the fittest strategy to maximize your own interests.

Meditation is a sacred act of finding the reason for one's existence in this critical moment called today.

It is an act of finding the best for oneself within one's family, neighborhood, community, and nation.

Have I ever recited "Om," requiring patience and endurance, at a set time and place? Do I know the one reason I exist in this world? "Om" is the voice of conscience for practitioners who set out to find it.

--- p.306

What should we practice? Patanjali used the Sanskrit phrase "eka-tattva" to describe the object of practice.

The Sanskrit word 'eka', meaning 'one', is the original form before the dualistic structure created to understand the human world.

Two appear through one.

Plotinus, a Roman philosopher and contemporary of Patanjali, explains that all things have one origin and that reality flows from that one origin.

He defined the first principle, which is the highest reality and the foundation of the universe, as 'to hen', or 'the one', in ancient Greek.

...

The second word in this phrase, tattva, literally means 'itself'.

'It-in-itself' is the essence and phenomenon of a thing or person.

It is the beginning and the end of an event.

It is both the cause and the result of a phenomenon.

Tattva is also the abstract concept we commonly refer to as 'truth'.

--- pp.339~340

By discovering and igniting the inner light, yoga practitioners can achieve mental tranquility to enter samadhi.

This inner light is 'Tao' for Lao-tzu, 'goodness and beauty' for Plato, 'existence' for Aristotle, 'infinity' for Plotinus, 'inner heaven' for Jesus, and 'ein sof', meaning 'infinity' in Judaism.

Although the inner light has been expressed in various terms in each culture, it ultimately refers to a universal consciousness that resides within humans and hopes to be awakened through experience.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who developed the Indian technique of Transcendental Meditation, says that when humans naturally enter and remain within themselves, they can experience what Emerson called "wise silence."

In line 36 of the Samadhi chapter, Patanjali introduces the practice of 'inner light' as a way for yoga practitioners to eliminate distracting thoughts in order to enter the state of samadhi.

--- p.370

Publisher's Review

The Yoga Sutras, a compilation of the tradition of mental training

Showing the way to peace of mind and spiritual freedom

Among the various schools of orthodox philosophy in India, yoga is the one that remains vibrant to this day, offering spiritual liberation, freedom, and balanced health for body and mind.

The Yoga Sutras, edited by Patanjali, are a collection of scriptures that compile India's long tradition of mental training into one volume, consisting of four chapters and a total of 195 scripture verses.

The purpose of the Yoga Sutras is to transform oneself into a completely different being through the holistic and integrated mind-body practice commonly known simply as 'yoga'.

To this end, the Yoga Sutras propose a new perspective on human consciousness.

It recognizes the accumulated experiences and memories that drive humans into suffering and suggests a way to escape from these bonds.

Because peace and freedom are only possible when we eliminate our attachment to the past.

Yoga practitioners meditate and immerse themselves in this practice, and through meditation, they take control of their daily lives and transform into their ideal selves.

Religion, philosophy, psychology, linguistics, etc.

The most modern interpretation, deeply examined from a humanities perspective.

The concise and condensed aphorisms in the Yoga Sutras compiled by Patanjali contain implicit meanings that are open to various interpretations.

To understand these verses, several commentaries were written in later generations.

Even this was difficult to understand as it was, so many commentaries on the commentaries, that is, many commentaries on the commentaries, were written again later.

『Bae Cheol-Hyeon's Yoga Sutra Lecture』 can be said to be a modern commentary that summarizes and explains the classical humanities of the East and the West that humanity has accumulated to date.

The author, a classical philologist and religious scholar, brings together classical humanities from the East and the West, including mythology, religion, philosophy, psychology, linguistics, and literature, from ancient times to the present day. He examines the meaning of the Yoga Sutra in depth and detail from various perspectives and suggests ways to put it into practice in everyday life.

Patanjali uses 'drashtuhu' (dra??u?) in the meaning of 'true self' in verse 3 of chapter 1, 'Samadhi'.

Why was 'Drashtuhu' used instead of 'Atman' or 'Purusha', which have similar meanings in Indian philosophy?

The author compares 'Drashtuhu (true self)' with the 'Allegory of the Cave' in Plato's 'Republic', the 'Hegemonicon' mentioned by Marcus Aurelius in 'Meditations', and Immatuel Kant's 'thing-in-itself', thereby conveying the hidden meaning of 'Drashtuhu' in a richer and more three-dimensional way.

Based on the Sanskrit original

A Classical Literature Scholar's Deeper and Broader Interpretation of the Yoga Sutras

The author Bae Cheol-hyeon's expertise as an expert in ancient Oriental languages, with extensive knowledge of ancient cuneiform, Indo-Iranian, Semitic (Aramaic), Greek, and Latin, is clearly evident in the text.

The author introduces the Devanagari of 51 sutras from the Samadhi chapter of the Yoga Sutras, explains Sanskrit words grammatically, and analyzes the etymology of important words in detail to help readers gain a deeper understanding of the sutras themselves.

Moreover, in-depth etymological analysis of words allows for easier understanding of the original meaning of the original text, rather than following traditional interpretations of the scriptures.

The first verse of the scripture is both the beginning and the whole.

Because it contains the core of what will unfold in the future.

What did Patanjali most want to say to practitioners embarking on spiritual and mental training to shed their old selves and transform into new ones? He begins with a sentence no one would expect.

The traditional translation of this first verse is:

“Now, begin your yoga training!” Most translations translate the first phrase as the title of the entire Yoga Sutra.

'Atha' means 'now' and 'yoganushasanam' means 'yoga training'.

Scholars sometimes translate this sentence simply as "Yoga Training" as the title of the entire Yoga Sutra.

I would like to translate this passage not as a title, but as the first sentence of a great scripture and a core sentence that reveals the spirit of yoga.

My translation is as follows:

“Now, pay attention.

“Yoga is a practice of immersing oneself in the ‘here and now.’”

- From pages 66-67 of the text

Even if you don't know any Sanskrit, if you read it slowly, one phrase at a time, you can experience the joy of deciphering the original text and pondering its meaning.

The first chapter, which summarizes the entire essence of the Yoga Sutra

The Path to Peace and Freedom Guided by the Samadhi Pum

The Yoga Sutras are composed of four chapters: Samadhi, Training, Manifestation, and Solitary Existence.

Among these, 『Bae Cheol-Hyeon's Yoga Sutra Lecture 1 - Samadhi』, which explains the Samadhi, was first introduced.

Afterwards, commentaries on “Training,” “Manifestation,” and “Dokjon” will be sequentially presented to readers.

Chapter 1 of the Yoga Sutra, “The Chapter on Samadhi,” is an introductory section that summarizes the essence of yoga.

In “Samadhapura,” we begin by examining the complex meaning and essential concepts of yoga.

By distinguishing and explaining the types of thoughts that govern human speech and behavior, it suggests methods for eliminating such thoughts (wandering thoughts) and also reveals the process of reaching peace of mind through them.

The peace of mind and spiritual freedom that yoga seeks can be achieved through systematic and logical meditation practice.

The Samadhi Chapter shows in detail how to control the swirling mind, attain the peace brought about by samadhi, and maintain spiritual freedom.

Yoga practitioners must first meditate and immerse themselves in their daily lives to perceive them as they are.

Then, you can take control of your daily life and reach your ideal self, your true self.

Yoga is a practice that frees me from the attachments that unconsciously and habitually control my thoughts, words, and actions.

What are the obsessions that prevent me from seeing the "abyss of the mind," where I discover my best self? What am I thinking about right now?

While editing the 51-line Samadhi chapter, Patanjali introduced Sanskrit words selected from the age-old Indian tradition to gradually transform the body, mind, and soul of yoga practitioners.

The profound meaning of a word can be discovered not through its Korean equivalent, but through a profound etymological analysis of the word.

For example, the Sanskrit word 'sam?dhi' is not an equivalent word that came from the Chinese character 'sammae', but means 'a transcendental state that is revealed when one arranges the sincere mind that everyone has in accordance with the order of the universe.'

I want to explore the profound meaning of words with my readers and apply it to our lives, transforming ourselves little by little every day.

- From page 14 of the text

The 51 verses of the Samadhi chapter are not mere metaphysical theories or thoughts.

I recommend that you read one verse a week, think about it, apply its meaning to your daily life, and practice it.

By breaking free from the obsessions that unconsciously control your thoughts, words, and actions, you will discover your true self and attain spiritual freedom.

Showing the way to peace of mind and spiritual freedom

Among the various schools of orthodox philosophy in India, yoga is the one that remains vibrant to this day, offering spiritual liberation, freedom, and balanced health for body and mind.

The Yoga Sutras, edited by Patanjali, are a collection of scriptures that compile India's long tradition of mental training into one volume, consisting of four chapters and a total of 195 scripture verses.

The purpose of the Yoga Sutras is to transform oneself into a completely different being through the holistic and integrated mind-body practice commonly known simply as 'yoga'.

To this end, the Yoga Sutras propose a new perspective on human consciousness.

It recognizes the accumulated experiences and memories that drive humans into suffering and suggests a way to escape from these bonds.

Because peace and freedom are only possible when we eliminate our attachment to the past.

Yoga practitioners meditate and immerse themselves in this practice, and through meditation, they take control of their daily lives and transform into their ideal selves.

Religion, philosophy, psychology, linguistics, etc.

The most modern interpretation, deeply examined from a humanities perspective.

The concise and condensed aphorisms in the Yoga Sutras compiled by Patanjali contain implicit meanings that are open to various interpretations.

To understand these verses, several commentaries were written in later generations.

Even this was difficult to understand as it was, so many commentaries on the commentaries, that is, many commentaries on the commentaries, were written again later.

『Bae Cheol-Hyeon's Yoga Sutra Lecture』 can be said to be a modern commentary that summarizes and explains the classical humanities of the East and the West that humanity has accumulated to date.

The author, a classical philologist and religious scholar, brings together classical humanities from the East and the West, including mythology, religion, philosophy, psychology, linguistics, and literature, from ancient times to the present day. He examines the meaning of the Yoga Sutra in depth and detail from various perspectives and suggests ways to put it into practice in everyday life.

Patanjali uses 'drashtuhu' (dra??u?) in the meaning of 'true self' in verse 3 of chapter 1, 'Samadhi'.

Why was 'Drashtuhu' used instead of 'Atman' or 'Purusha', which have similar meanings in Indian philosophy?

The author compares 'Drashtuhu (true self)' with the 'Allegory of the Cave' in Plato's 'Republic', the 'Hegemonicon' mentioned by Marcus Aurelius in 'Meditations', and Immatuel Kant's 'thing-in-itself', thereby conveying the hidden meaning of 'Drashtuhu' in a richer and more three-dimensional way.

Based on the Sanskrit original

A Classical Literature Scholar's Deeper and Broader Interpretation of the Yoga Sutras

The author Bae Cheol-hyeon's expertise as an expert in ancient Oriental languages, with extensive knowledge of ancient cuneiform, Indo-Iranian, Semitic (Aramaic), Greek, and Latin, is clearly evident in the text.

The author introduces the Devanagari of 51 sutras from the Samadhi chapter of the Yoga Sutras, explains Sanskrit words grammatically, and analyzes the etymology of important words in detail to help readers gain a deeper understanding of the sutras themselves.

Moreover, in-depth etymological analysis of words allows for easier understanding of the original meaning of the original text, rather than following traditional interpretations of the scriptures.

The first verse of the scripture is both the beginning and the whole.

Because it contains the core of what will unfold in the future.

What did Patanjali most want to say to practitioners embarking on spiritual and mental training to shed their old selves and transform into new ones? He begins with a sentence no one would expect.

The traditional translation of this first verse is:

“Now, begin your yoga training!” Most translations translate the first phrase as the title of the entire Yoga Sutra.

'Atha' means 'now' and 'yoganushasanam' means 'yoga training'.

Scholars sometimes translate this sentence simply as "Yoga Training" as the title of the entire Yoga Sutra.

I would like to translate this passage not as a title, but as the first sentence of a great scripture and a core sentence that reveals the spirit of yoga.

My translation is as follows:

“Now, pay attention.

“Yoga is a practice of immersing oneself in the ‘here and now.’”

- From pages 66-67 of the text

Even if you don't know any Sanskrit, if you read it slowly, one phrase at a time, you can experience the joy of deciphering the original text and pondering its meaning.

The first chapter, which summarizes the entire essence of the Yoga Sutra

The Path to Peace and Freedom Guided by the Samadhi Pum

The Yoga Sutras are composed of four chapters: Samadhi, Training, Manifestation, and Solitary Existence.

Among these, 『Bae Cheol-Hyeon's Yoga Sutra Lecture 1 - Samadhi』, which explains the Samadhi, was first introduced.

Afterwards, commentaries on “Training,” “Manifestation,” and “Dokjon” will be sequentially presented to readers.

Chapter 1 of the Yoga Sutra, “The Chapter on Samadhi,” is an introductory section that summarizes the essence of yoga.

In “Samadhapura,” we begin by examining the complex meaning and essential concepts of yoga.

By distinguishing and explaining the types of thoughts that govern human speech and behavior, it suggests methods for eliminating such thoughts (wandering thoughts) and also reveals the process of reaching peace of mind through them.

The peace of mind and spiritual freedom that yoga seeks can be achieved through systematic and logical meditation practice.

The Samadhi Chapter shows in detail how to control the swirling mind, attain the peace brought about by samadhi, and maintain spiritual freedom.

Yoga practitioners must first meditate and immerse themselves in their daily lives to perceive them as they are.

Then, you can take control of your daily life and reach your ideal self, your true self.

Yoga is a practice that frees me from the attachments that unconsciously and habitually control my thoughts, words, and actions.

What are the obsessions that prevent me from seeing the "abyss of the mind," where I discover my best self? What am I thinking about right now?

While editing the 51-line Samadhi chapter, Patanjali introduced Sanskrit words selected from the age-old Indian tradition to gradually transform the body, mind, and soul of yoga practitioners.

The profound meaning of a word can be discovered not through its Korean equivalent, but through a profound etymological analysis of the word.

For example, the Sanskrit word 'sam?dhi' is not an equivalent word that came from the Chinese character 'sammae', but means 'a transcendental state that is revealed when one arranges the sincere mind that everyone has in accordance with the order of the universe.'

I want to explore the profound meaning of words with my readers and apply it to our lives, transforming ourselves little by little every day.

- From page 14 of the text

The 51 verses of the Samadhi chapter are not mere metaphysical theories or thoughts.

I recommend that you read one verse a week, think about it, apply its meaning to your daily life, and practice it.

By breaking free from the obsessions that unconsciously control your thoughts, words, and actions, you will discover your true self and attain spiritual freedom.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 16, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 504 pages | 694g | 152*215*25mm

- ISBN13: 9788934961833

- ISBN10: 893496183X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)