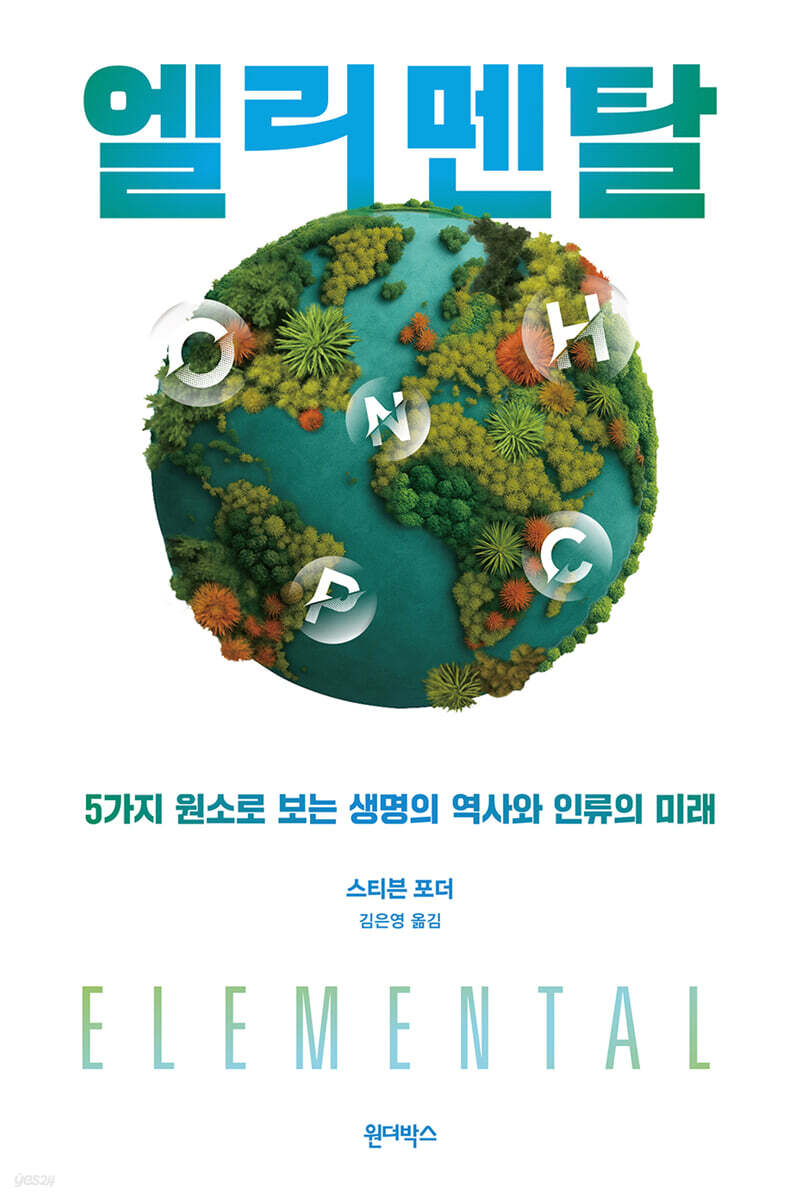

Elemental

|

Description

Book Introduction

The 4-billion-Year History of Life on Earth Through Five Elements

What was the most significant change on Earth? Was it a massive asteroid impact or a volcanic eruption? This book, "Elementals," argues that the greatest change on Earth was "life," and that five elements underlie this change.

Brown University ecologist Stephen Fodor traces the 4 billion-year history of life, focusing on hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P).

The efforts of living organisms to obtain these elements that make up the 'Formula of Life: HOCNP' have become the driving force of evolution and have even completely changed the Earth itself.

Bacteria, terrestrial plants and we humans have been the most successful at this and have become 'world changers'.

But the success of these three world changers brought about an unexpected disaster.

Although cyanobacteria achieved innovations such as photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation, they also filled the atmosphere with oxygen, causing mass extinction of microorganisms that thrived in oxygen-deprived environments.

Terrestrial plants covered the continents in greenery, thanks to their ability to mine phosphorus from water and rock, but they also froze the planet by absorbing too much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

And we humans are rapidly warming the Earth by using large amounts of carbon energy.

Can humanity, unlike our "world changers" predecessors, avoid environmental catastrophe and find a different path? This book combines a compelling narrative with cutting-edge science to offer a fresh and captivating perspective on the planet's crisis and the direction we must take.

What was the most significant change on Earth? Was it a massive asteroid impact or a volcanic eruption? This book, "Elementals," argues that the greatest change on Earth was "life," and that five elements underlie this change.

Brown University ecologist Stephen Fodor traces the 4 billion-year history of life, focusing on hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P).

The efforts of living organisms to obtain these elements that make up the 'Formula of Life: HOCNP' have become the driving force of evolution and have even completely changed the Earth itself.

Bacteria, terrestrial plants and we humans have been the most successful at this and have become 'world changers'.

But the success of these three world changers brought about an unexpected disaster.

Although cyanobacteria achieved innovations such as photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation, they also filled the atmosphere with oxygen, causing mass extinction of microorganisms that thrived in oxygen-deprived environments.

Terrestrial plants covered the continents in greenery, thanks to their ability to mine phosphorus from water and rock, but they also froze the planet by absorbing too much carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

And we humans are rapidly warming the Earth by using large amounts of carbon energy.

Can humanity, unlike our "world changers" predecessors, avoid environmental catastrophe and find a different path? This book combines a compelling narrative with cutting-edge science to offer a fresh and captivating perspective on the planet's crisis and the direction we must take.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: The Smallest and Greatest Things That Change the World

Part 1: Lessons from the Past

1 The greatest environmental change on earth

2 Plants Conquer the Continent

Part 2: Humanity Dominates the Elements

3 The destructive cycle of humans, carbon, and energy

4. How to find the cause of climate change

5 Nitrogen, the magical Goldilocks element

6 people, irreplaceable white gold

7 Water, the core of terrestrial life

Part 3: The Path to the Future

8 Biogeochemical Luck

9 Puzzles Still Remaining

Acknowledgements

annotation

Part 1: Lessons from the Past

1 The greatest environmental change on earth

2 Plants Conquer the Continent

Part 2: Humanity Dominates the Elements

3 The destructive cycle of humans, carbon, and energy

4. How to find the cause of climate change

5 Nitrogen, the magical Goldilocks element

6 people, irreplaceable white gold

7 Water, the core of terrestrial life

Part 3: The Path to the Future

8 Biogeochemical Luck

9 Puzzles Still Remaining

Acknowledgements

annotation

Detailed image

Into the book

The thread connecting these organisms and the great changes they triggered, deep within the unimaginable depths of geologic time, is woven from five elements that make up more than 99 percent of all living cells.

These are hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P).

I call these elements the 'Formula of Life: HOCNP'.

All organisms, whether large or small, tirelessly and persistently seek out and gather these elements.

The organisms that succeed here survive.

Organisms that cannot do so cannot survive.

As evolutionary processes evolve, new organisms emerge that harness these elements in more ingenious and efficient ways, setting the stage for those organisms to transform the world.

--- p.10

Because of this disconnected education, I never truly understood what it meant to live on a 'living planet'.

Of course, this basically means that there is life on Earth.

But more importantly, it implies that Earth is a planet formed by life itself, specifically by organisms that influence the flow of elements in the formula for life.

After reading this book, I hope readers will understand the changes Earth has undergone in the past by viewing the rapid and multifaceted changes humans have brought about on Earth in our time through the lens of these five elements.

More importantly, I hope this way of thinking about the world will help us move toward a more sustainable future.

--- p.18~19

We can learn one more thing from the great oxidation event brought about by Nam Se-gyun.

If an organism can evolve to change the flow of just one or two elements of the formula for life, it can outcompete and thrive.

Since these elements are also closely related to climate, changes in the flow of these elements can change the world.

In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that the flow of these elements between organisms and their surrounding environment, the biogeochemical cycle, is the chemical heartbeat of the Earth.

--- p.51

However, as plant evolution took enough CO2 out of the air, the greenhouse effect eventually began to weaken.

During a time when the entire Earth had a tropical climate, forests grew and became denser on land at a rapid rate, but the Earth's temperature began to drop noticeably.

It is not clear exactly how long it took for the Earth to experience an ice age.

But about 300 million years ago, roughly 100 million years after plants began to colonize the Earth in earnest, the Earth cooled enough to wipe out most of its rainforests.

The plants were forced to freeze to death in exchange for their success in survival and reproduction.

Evolutionary innovation and prosperity have once again brought about environmental disaster as a tragic side effect.

--- p.78~79

Humanity is also found to be unique compared to any other life form that has ever existed.

We simply did what the world changers before us did.

Humanity has discovered new ways to extract energy from carbon, and we are using them to our advantage.

Based on what we understand so far, the question is not whether we can change this planet or not.

The question is whether we can use fossil fuels in this way without their negative consequences changing the Earth's climate.

--- p.104

To put it bluntly, the problem with nitrogen is this:

Both humans and crops essential to human life require reactive nitrogen to make the proteins that make up their bodies.

Nitrogen is an abundant gas in the air, but it is not very reactive.

In fact, for the first 4 billion years of Earth's existence, only single-celled organisms existed, and one of them, cyanobacteria, had access to inert nitrogen in the air.

The remaining organisms used the cyanobacteria to introduce new reactive nitrogen into the food chain.

This chapter will tell the story of how human innovations disrupted Earth's equilibrium, transforming it from a planet where reactive nitrogen was scarce to one where it was abundant.

--- p.140

Modern human society is built on several very different pillars.

Each pillar has its own strengths and weaknesses, but we depend on all of them simultaneously.

Carbon-based fossil fuels, which provide energy, are finite but replaceable.

Nitrogen, which provides food, is infinite but irreplaceable.

What about the third element, phosphorus? Unfortunately, phosphorus is finite and irreplaceable.

Therefore, it is a dangerous pillar to rely on without any countermeasures.

But we cannot help but rely on this pillar, for it is written in the formula of life.

--- p.160

My field of study, biogeochemistry, has its roots in agriculture.

To grow crops, farmers must understand their biology, know temperature, sunlight, rainfall, and which crops grow best in which soil.

So, ‘biology’, ‘earth science’, and ‘chemistry’ met.

Readers who have read this far will readily understand that biogeochemistry is fundamental to solving the greatest environmental challenges facing humanity.

And this applies equally to the biggest problem of all: climate change.

--- p.210

Our reliance on carbon as an energy source to sustain our current lifestyle is different from the way our world-changing ancestors relied on carbon.

Cyanobacteria and plants have changed the Earth's carbon cycle through their internal metabolism.

Humans are changing the carbon cycle by running everything on fossil fuels, that is, by metabolic processes outside our bodies.

But our external metabolic processes do not necessarily have to be carbon-based and emit greenhouse gases.

--- p.248

The point is this.

When an element is scarce, evolution selects for traits that utilize that element efficiently.

On the other hand, ecosystems use abundant materials less efficiently.

The keys to success are conservation and recycling, but both work only on poor materials.

With this in mind, let us now consider how humans utilize these same elements.

Again, before scarcity and side effects force us to do so, we have time to learn from our world-changing ancestors and create opportunities to change our behavior based on those lessons.

These are hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P).

I call these elements the 'Formula of Life: HOCNP'.

All organisms, whether large or small, tirelessly and persistently seek out and gather these elements.

The organisms that succeed here survive.

Organisms that cannot do so cannot survive.

As evolutionary processes evolve, new organisms emerge that harness these elements in more ingenious and efficient ways, setting the stage for those organisms to transform the world.

--- p.10

Because of this disconnected education, I never truly understood what it meant to live on a 'living planet'.

Of course, this basically means that there is life on Earth.

But more importantly, it implies that Earth is a planet formed by life itself, specifically by organisms that influence the flow of elements in the formula for life.

After reading this book, I hope readers will understand the changes Earth has undergone in the past by viewing the rapid and multifaceted changes humans have brought about on Earth in our time through the lens of these five elements.

More importantly, I hope this way of thinking about the world will help us move toward a more sustainable future.

--- p.18~19

We can learn one more thing from the great oxidation event brought about by Nam Se-gyun.

If an organism can evolve to change the flow of just one or two elements of the formula for life, it can outcompete and thrive.

Since these elements are also closely related to climate, changes in the flow of these elements can change the world.

In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that the flow of these elements between organisms and their surrounding environment, the biogeochemical cycle, is the chemical heartbeat of the Earth.

--- p.51

However, as plant evolution took enough CO2 out of the air, the greenhouse effect eventually began to weaken.

During a time when the entire Earth had a tropical climate, forests grew and became denser on land at a rapid rate, but the Earth's temperature began to drop noticeably.

It is not clear exactly how long it took for the Earth to experience an ice age.

But about 300 million years ago, roughly 100 million years after plants began to colonize the Earth in earnest, the Earth cooled enough to wipe out most of its rainforests.

The plants were forced to freeze to death in exchange for their success in survival and reproduction.

Evolutionary innovation and prosperity have once again brought about environmental disaster as a tragic side effect.

--- p.78~79

Humanity is also found to be unique compared to any other life form that has ever existed.

We simply did what the world changers before us did.

Humanity has discovered new ways to extract energy from carbon, and we are using them to our advantage.

Based on what we understand so far, the question is not whether we can change this planet or not.

The question is whether we can use fossil fuels in this way without their negative consequences changing the Earth's climate.

--- p.104

To put it bluntly, the problem with nitrogen is this:

Both humans and crops essential to human life require reactive nitrogen to make the proteins that make up their bodies.

Nitrogen is an abundant gas in the air, but it is not very reactive.

In fact, for the first 4 billion years of Earth's existence, only single-celled organisms existed, and one of them, cyanobacteria, had access to inert nitrogen in the air.

The remaining organisms used the cyanobacteria to introduce new reactive nitrogen into the food chain.

This chapter will tell the story of how human innovations disrupted Earth's equilibrium, transforming it from a planet where reactive nitrogen was scarce to one where it was abundant.

--- p.140

Modern human society is built on several very different pillars.

Each pillar has its own strengths and weaknesses, but we depend on all of them simultaneously.

Carbon-based fossil fuels, which provide energy, are finite but replaceable.

Nitrogen, which provides food, is infinite but irreplaceable.

What about the third element, phosphorus? Unfortunately, phosphorus is finite and irreplaceable.

Therefore, it is a dangerous pillar to rely on without any countermeasures.

But we cannot help but rely on this pillar, for it is written in the formula of life.

--- p.160

My field of study, biogeochemistry, has its roots in agriculture.

To grow crops, farmers must understand their biology, know temperature, sunlight, rainfall, and which crops grow best in which soil.

So, ‘biology’, ‘earth science’, and ‘chemistry’ met.

Readers who have read this far will readily understand that biogeochemistry is fundamental to solving the greatest environmental challenges facing humanity.

And this applies equally to the biggest problem of all: climate change.

--- p.210

Our reliance on carbon as an energy source to sustain our current lifestyle is different from the way our world-changing ancestors relied on carbon.

Cyanobacteria and plants have changed the Earth's carbon cycle through their internal metabolism.

Humans are changing the carbon cycle by running everything on fossil fuels, that is, by metabolic processes outside our bodies.

But our external metabolic processes do not necessarily have to be carbon-based and emit greenhouse gases.

--- p.248

The point is this.

When an element is scarce, evolution selects for traits that utilize that element efficiently.

On the other hand, ecosystems use abundant materials less efficiently.

The keys to success are conservation and recycling, but both work only on poor materials.

With this in mind, let us now consider how humans utilize these same elements.

Again, before scarcity and side effects force us to do so, we have time to learn from our world-changing ancestors and create opportunities to change our behavior based on those lessons.

--- p.259

Publisher's Review

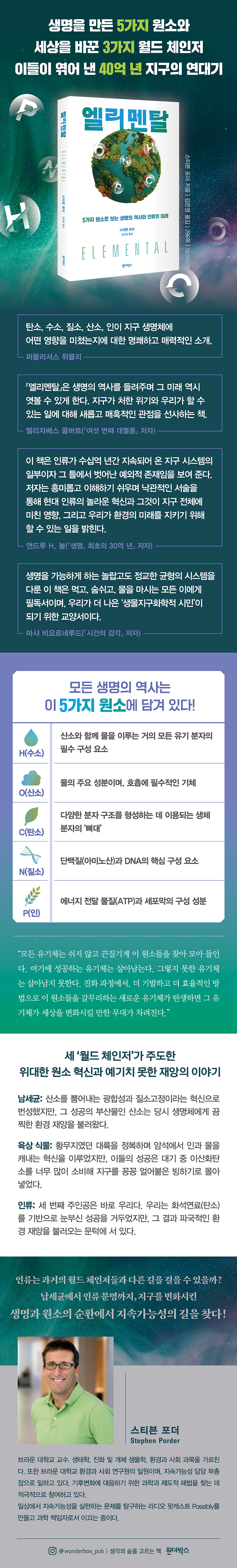

Three Lifeforms and Five Elements That Changed the Earth

The 4 billion-year history of life on Earth is a drama of continuous change and innovation.

And at the center of that drama are five elements: hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P).

Hydrogen, along with oxygen, forms water and is an essential component of almost all organic molecules.

Oxygen is also a component of water and is essential for breathing life.

Carbon is the 'skeleton' of biomolecules, used to form various molecular structures.

Nitrogen is a key component of proteins (amino acids) and DNA.

Phosphorus is a component of ATP, an energy carrier, and cell membranes.

How well we secure these elements, which make up 99% of the cells of all living organisms, determines the survival and prosperity of living organisms.

In Earth's long history, three types of life have achieved remarkable success in this endeavor.

Bacteria, terrestrial plants, and us humans.

These three protagonists not only became winners of evolution by achieving remarkable innovations in the use of elements, but also became 'World Changers' who changed the environment of the Earth itself.

This book traces how life has utilized five key elements to thrive and drive global change.

What can we learn from this as we bring about yet another transformation on Earth?

Life's Great Innovations and Unexpected Catastrophes

The first world changer was Nam Se-gyun.

The bacteria were able to prosper enormously by developing a method of photosynthesis, which uses solar energy to capture carbon from seawater to create nutrients, and by fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere.

Cyanobacteria released massive amounts of oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis, turning Earth, which had been almost oxygen-poor until then, into an oxygen-rich planet.

This 'Great Oxidation Event' set the stage for the emergence of multicellular life forms, including humans, but ironically, it was a huge environmental disaster for the anaerobic life forms that made up the majority of life on Earth at the time.

Most of those that could not survive in oxygen-rich environments became extinct, and today they remain only in limited environments such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

The second world changer was terrestrial plants.

The ocean is full of water (oxygen and hydrogen), and carbon and nitrogen can be obtained through photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation.

But phosphorus was very rare in the sea.

Because phosphorus is contained in rocks, to obtain phosphorus one had to go on land and access the rocks.

About 2 billion years after the cyanobacteria, terrestrial plants did this.

Plants have evolved the ability to use their roots to extract essential phosphorus from rocks and to draw up water.

As plants spread across the globe, the Earth became a truly green planet.

But the explosive growth of plants has also brought about environmental disaster.

As a result of absorbing large amounts of carbon dioxide from the air for photosynthesis, the greenhouse effect that kept the Earth warm weakened, and the Earth began to gradually cool down.

About 100 million years later, the Earth had cooled enough to cause most of the rainforests to disappear.

The third is us humans.

Since humans discovered how to use carbon energy, they have been releasing carbon into the atmosphere at an incredible rate.

Plants have lowered carbon dioxide levels by 36 ppm every million years, while humans have raised carbon dioxide levels from 280 ppm to 416 ppm (as of June 2020) in just 200 years, and are continuing to increase them by 4 ppm each year.

The global average temperature has risen by 1.1 degrees Celsius in 100 years, and may rise to 3.8 degrees Celsius by the end of the 21st century.

The pattern of innovation in elemental use becoming an environmental disaster is repeating itself.

Humanity's Success and the Broken Elemental Cycle

Humanity has also achieved unprecedented success in securing water (oxygen and hydrogen), nitrogen, and phosphorus, and here too, similar side effects are occurring.

Until the 20th century, only bacteria such as cyanobacteria could fix and utilize nitrogen in the atmosphere.

In the early 20th century, Fritz Haber invented nitrogen fixation, allowing humans to produce nitrogen fertilizers at will, which led to a dramatic increase in food production.

But now we are overusing nitrogen fertilizers as much as we can get.

Of the nitrogen fertilizers spread on farmland, only about 13 percent become nutrients and reach people, and the rest flows into rivers, oceans, and the atmosphere, causing pollution.

Phosphorus is a more precious element than nitrogen in nature.

So plants have evolved ways to use phosphorus without wasting any of it.

Phosphorus was so precious to humans that it was called "white gold," and animal bones and the sedimentary excrement of seabirds were the only ways to obtain high concentrations of phosphorus.

Production has now increased significantly, with phosphorus ore being mined in West African mines.

However, the fact remains that phosphorus, unlike fossil fuels, is a finite resource that cannot be replaced and cannot be artificially produced like nitrogen fertilizer.

Before the phosphorus mines run dry, we must learn how to use phosphorus as efficiently as plants.

We also need to be more efficient in our water use.

Humans use about 4 trillion cubic meters of water a year.

This is enough to cover the entire United States by about 50 centimeters, and most of it is used for agricultural purposes.

Even in arid lands, huge amounts of water are pumped from underground to support farming, and as a result, the water level in groundwater aquifers is falling every year.

Climate change, which will accelerate in the future, is an issue that cannot be overlooked as it will make water supply more difficult.

Other futures we can go to

Neither bacteria nor terrestrial plants have escaped the disasters brought about by their own success.

However, the author says that humans have two special advantages over the previous two beings.

First, we have the ability to learn from the past and predict the future.

Second, and more importantly, the environmental problems we face do not arise from internal metabolism, which is essential for survival, as in bacteria or plants, but rather from readily replaceable external energy consumption (primarily fossil fuel combustion).

Bacteria had to release oxygen to survive, and plants had no choice but to absorb carbon dioxide.

But not humanity.

We can get the energy we need without emitting carbon dioxide.

We can change humanity's linear way of using elements into a circular way.

"Elemental" presents a vision for the future of humanity at this very point.

If we can break the cycle of energy consumption and carbon emissions and restructure the element cycle in a sustainable way, we can continue to prosper without repeating tragic patterns.

The path may not be easy, but it is a path of hope that our ancestors could not choose.

If we can anticipate the future and change our behavior, we can move toward a different future.

This book will serve as a timely guide to that path.

The 4 billion-year history of life on Earth is a drama of continuous change and innovation.

And at the center of that drama are five elements: hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P).

Hydrogen, along with oxygen, forms water and is an essential component of almost all organic molecules.

Oxygen is also a component of water and is essential for breathing life.

Carbon is the 'skeleton' of biomolecules, used to form various molecular structures.

Nitrogen is a key component of proteins (amino acids) and DNA.

Phosphorus is a component of ATP, an energy carrier, and cell membranes.

How well we secure these elements, which make up 99% of the cells of all living organisms, determines the survival and prosperity of living organisms.

In Earth's long history, three types of life have achieved remarkable success in this endeavor.

Bacteria, terrestrial plants, and us humans.

These three protagonists not only became winners of evolution by achieving remarkable innovations in the use of elements, but also became 'World Changers' who changed the environment of the Earth itself.

This book traces how life has utilized five key elements to thrive and drive global change.

What can we learn from this as we bring about yet another transformation on Earth?

Life's Great Innovations and Unexpected Catastrophes

The first world changer was Nam Se-gyun.

The bacteria were able to prosper enormously by developing a method of photosynthesis, which uses solar energy to capture carbon from seawater to create nutrients, and by fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere.

Cyanobacteria released massive amounts of oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis, turning Earth, which had been almost oxygen-poor until then, into an oxygen-rich planet.

This 'Great Oxidation Event' set the stage for the emergence of multicellular life forms, including humans, but ironically, it was a huge environmental disaster for the anaerobic life forms that made up the majority of life on Earth at the time.

Most of those that could not survive in oxygen-rich environments became extinct, and today they remain only in limited environments such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

The second world changer was terrestrial plants.

The ocean is full of water (oxygen and hydrogen), and carbon and nitrogen can be obtained through photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation.

But phosphorus was very rare in the sea.

Because phosphorus is contained in rocks, to obtain phosphorus one had to go on land and access the rocks.

About 2 billion years after the cyanobacteria, terrestrial plants did this.

Plants have evolved the ability to use their roots to extract essential phosphorus from rocks and to draw up water.

As plants spread across the globe, the Earth became a truly green planet.

But the explosive growth of plants has also brought about environmental disaster.

As a result of absorbing large amounts of carbon dioxide from the air for photosynthesis, the greenhouse effect that kept the Earth warm weakened, and the Earth began to gradually cool down.

About 100 million years later, the Earth had cooled enough to cause most of the rainforests to disappear.

The third is us humans.

Since humans discovered how to use carbon energy, they have been releasing carbon into the atmosphere at an incredible rate.

Plants have lowered carbon dioxide levels by 36 ppm every million years, while humans have raised carbon dioxide levels from 280 ppm to 416 ppm (as of June 2020) in just 200 years, and are continuing to increase them by 4 ppm each year.

The global average temperature has risen by 1.1 degrees Celsius in 100 years, and may rise to 3.8 degrees Celsius by the end of the 21st century.

The pattern of innovation in elemental use becoming an environmental disaster is repeating itself.

Humanity's Success and the Broken Elemental Cycle

Humanity has also achieved unprecedented success in securing water (oxygen and hydrogen), nitrogen, and phosphorus, and here too, similar side effects are occurring.

Until the 20th century, only bacteria such as cyanobacteria could fix and utilize nitrogen in the atmosphere.

In the early 20th century, Fritz Haber invented nitrogen fixation, allowing humans to produce nitrogen fertilizers at will, which led to a dramatic increase in food production.

But now we are overusing nitrogen fertilizers as much as we can get.

Of the nitrogen fertilizers spread on farmland, only about 13 percent become nutrients and reach people, and the rest flows into rivers, oceans, and the atmosphere, causing pollution.

Phosphorus is a more precious element than nitrogen in nature.

So plants have evolved ways to use phosphorus without wasting any of it.

Phosphorus was so precious to humans that it was called "white gold," and animal bones and the sedimentary excrement of seabirds were the only ways to obtain high concentrations of phosphorus.

Production has now increased significantly, with phosphorus ore being mined in West African mines.

However, the fact remains that phosphorus, unlike fossil fuels, is a finite resource that cannot be replaced and cannot be artificially produced like nitrogen fertilizer.

Before the phosphorus mines run dry, we must learn how to use phosphorus as efficiently as plants.

We also need to be more efficient in our water use.

Humans use about 4 trillion cubic meters of water a year.

This is enough to cover the entire United States by about 50 centimeters, and most of it is used for agricultural purposes.

Even in arid lands, huge amounts of water are pumped from underground to support farming, and as a result, the water level in groundwater aquifers is falling every year.

Climate change, which will accelerate in the future, is an issue that cannot be overlooked as it will make water supply more difficult.

Other futures we can go to

Neither bacteria nor terrestrial plants have escaped the disasters brought about by their own success.

However, the author says that humans have two special advantages over the previous two beings.

First, we have the ability to learn from the past and predict the future.

Second, and more importantly, the environmental problems we face do not arise from internal metabolism, which is essential for survival, as in bacteria or plants, but rather from readily replaceable external energy consumption (primarily fossil fuel combustion).

Bacteria had to release oxygen to survive, and plants had no choice but to absorb carbon dioxide.

But not humanity.

We can get the energy we need without emitting carbon dioxide.

We can change humanity's linear way of using elements into a circular way.

"Elemental" presents a vision for the future of humanity at this very point.

If we can break the cycle of energy consumption and carbon emissions and restructure the element cycle in a sustainable way, we can continue to prosper without repeating tragic patterns.

The path may not be easy, but it is a path of hope that our ancestors could not choose.

If we can anticipate the future and change our behavior, we can move toward a different future.

This book will serve as a timely guide to that path.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 21, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 296 pages | 388g | 140*210*18mm

- ISBN13: 9791192953663

- ISBN10: 1192953665

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)