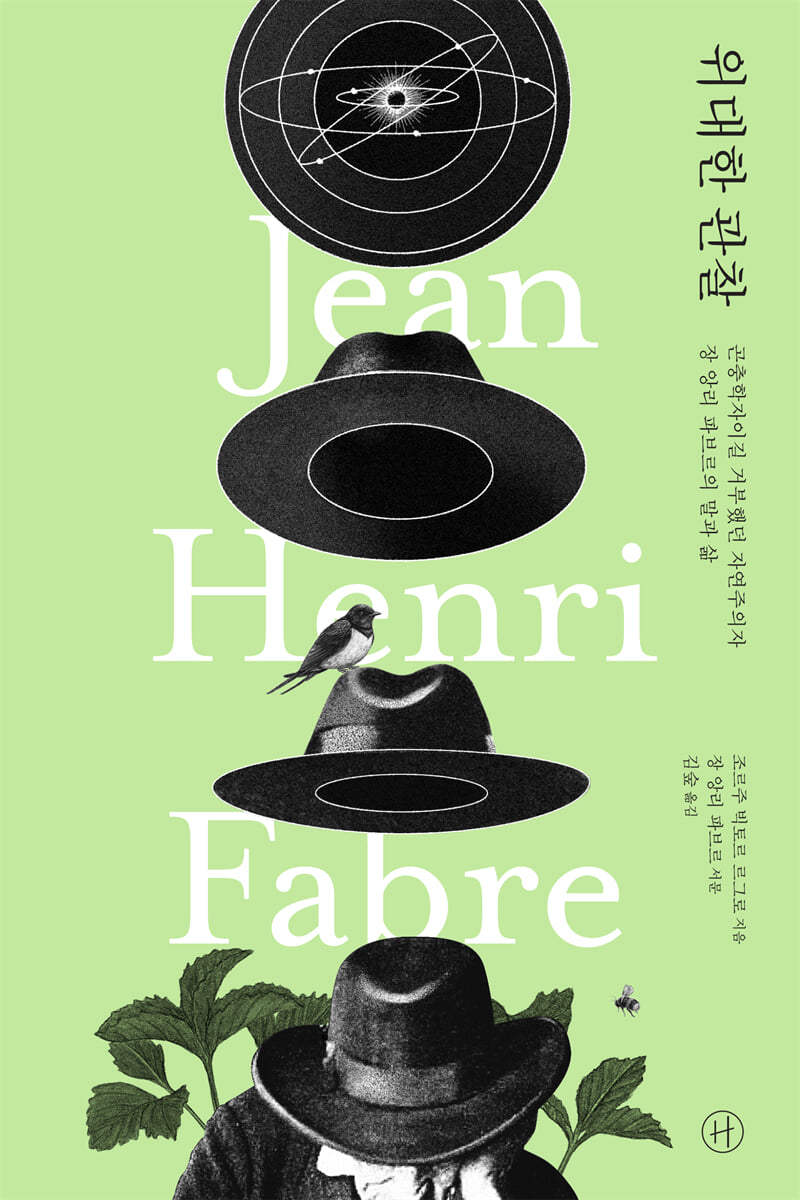

Great observation

|

Description

Book Introduction

Because of Fabre, we

I saw a world full of miracles and poetry

The great observer Fabre, in his last book

Offering green poetry to all those who cherish nature.

★Praise from those who read this book first★

“A record of one human being’s struggle to sing of the beauty of life on Earth for a long time without any interference.” ─ Shin Hye-woo (Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, USA)

“Just as Fabre’s book gave us the courage to love nature, this book makes Fabre himself the subject of observation, allowing us to understand the species called Homo sapiens.” ─ Lee So-young (botanical artist, horticultural researcher)

This book is a biography and memoir containing the words and life of Jean-Henri Fabre, widely known for his works “Fabre's Book of Plants” and “Fabre's Book of Insects.”

It is particularly noteworthy in that it focuses on aspects of nature that humanity has previously overlooked, and on the choices made in life by scientists who revealed them.

Contrary to popular belief, Fabre, a naturalist who refused to be called an entomologist, has a profound resonance with us today in his perspective and ethics on nature.

With climate change, the climate crisis, and now climate disaster looming, our worldview demands a change.

This attitude of expanding oneself to the world, from the days when 'I' and 'we' were the standards of life to 'them' and 'humanity', and further, to all living species and the entire universe, is perhaps the greatest thing that humans can do.

The first thing we must do when faced with a world we have never experienced before is to look at it like Fabre, to shake off any preconceived notions and face the phenomenon and observe it.

Let us experience an expansion of existence like no other through the words and life of Fabre, the great observer who dedicated his entire life to revealing the cosmos above the earth and expanding the world in his own unique way, the very man whom Charles Darwin called “the inimitable observer” in his masterpiece, “The Origin of Species,” which shook the very foundations of our understanding of life.

I saw a world full of miracles and poetry

The great observer Fabre, in his last book

Offering green poetry to all those who cherish nature.

★Praise from those who read this book first★

“A record of one human being’s struggle to sing of the beauty of life on Earth for a long time without any interference.” ─ Shin Hye-woo (Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, USA)

“Just as Fabre’s book gave us the courage to love nature, this book makes Fabre himself the subject of observation, allowing us to understand the species called Homo sapiens.” ─ Lee So-young (botanical artist, horticultural researcher)

This book is a biography and memoir containing the words and life of Jean-Henri Fabre, widely known for his works “Fabre's Book of Plants” and “Fabre's Book of Insects.”

It is particularly noteworthy in that it focuses on aspects of nature that humanity has previously overlooked, and on the choices made in life by scientists who revealed them.

Contrary to popular belief, Fabre, a naturalist who refused to be called an entomologist, has a profound resonance with us today in his perspective and ethics on nature.

With climate change, the climate crisis, and now climate disaster looming, our worldview demands a change.

This attitude of expanding oneself to the world, from the days when 'I' and 'we' were the standards of life to 'them' and 'humanity', and further, to all living species and the entire universe, is perhaps the greatest thing that humans can do.

The first thing we must do when faced with a world we have never experienced before is to look at it like Fabre, to shake off any preconceived notions and face the phenomenon and observe it.

Let us experience an expansion of existence like no other through the words and life of Fabre, the great observer who dedicated his entire life to revealing the cosmos above the earth and expanding the world in his own unique way, the very man whom Charles Darwin called “the inimitable observer” in his masterpiece, “The Origin of Species,” which shook the very foundations of our understanding of life.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction by Jean-Henri Fabre

Introduction

Chapter 1: Nature's Intuition

Chapter 2 Elementary School Teacher

Chapter 3 Corsica

Chapter 4 In Avignon

Chapter 5: The Great Teacher

Chapter 6 Hideout

Chapter 7: Interpreting Nature

Chapter 8: The Miracle of Instinct

Chapter 9 Evolution or “Biological Variation”

Chapter 10: The Mind of Animals

Chapter 11 Harmony and Disharmony

Chapter 12: Understanding Nature

Chapter 13: The Epic of Animal Life

Chapter 14 Parallel Universes

Chapter 15: The Last Years in Serignan

Chapter 16: Twilight

Americas

Jean Henri Fabre's Chronology

Appendix Source

Introduction

Chapter 1: Nature's Intuition

Chapter 2 Elementary School Teacher

Chapter 3 Corsica

Chapter 4 In Avignon

Chapter 5: The Great Teacher

Chapter 6 Hideout

Chapter 7: Interpreting Nature

Chapter 8: The Miracle of Instinct

Chapter 9 Evolution or “Biological Variation”

Chapter 10: The Mind of Animals

Chapter 11 Harmony and Disharmony

Chapter 12: Understanding Nature

Chapter 13: The Epic of Animal Life

Chapter 14 Parallel Universes

Chapter 15: The Last Years in Serignan

Chapter 16: Twilight

Americas

Jean Henri Fabre's Chronology

Appendix Source

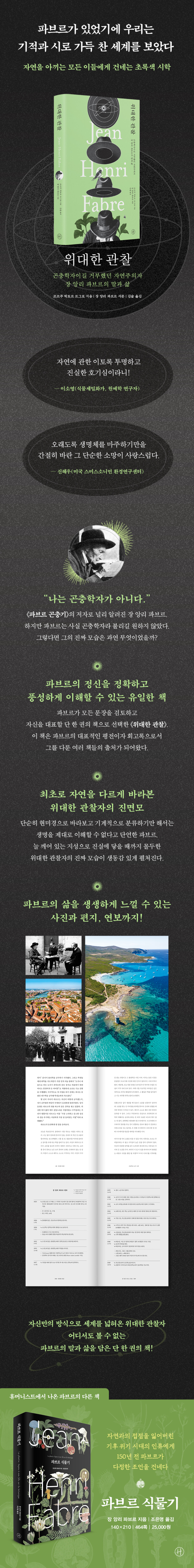

Detailed image

Into the book

After this dazzling success, why didn't Fabre pursue the professorship exam, which would have avoided the numerous disappointments he faced later in his career? There's no doubt that Fabre's ideal future lay elsewhere, and he vaguely felt he was on the wrong path.

Despite all the requests addressed to Fabre, he only thought about “the work he loved in the field of natural history.”

Fabre feared that he would lose precious time by “compromising this labor which he felt was pointless” with the research he had already begun in preparation for the selection exams and the explorations he was undertaking in Corsica.

Fabre was busy with his first original research, which he was preparing for his doctorate in natural sciences.

--- From "In Avignon"

Fabre, who observed people as well as animals, looked at the emperor quietly.

The “quite simple” emperor, who rarely showed emotion, exchanged a few words with Fabre, his eyes half-closed.

Fabre watched as “large beetle-like attendants with café-au-lait colored wings came and went, wearing breeches and silver-buckled shoes, and moving with a ceremonial gait.”

Fabre already sighed in regret.

It was boring.

It was terribly painful, and no matter what happened in the world, I never wanted to repeat that experience again.

--- From "In Avignon"

Fabre was able to fully display his talent because it belonged entirely to himself.

For a scholar, explorer, and outdoor observer like Fabre, freedom and leisure were more than just essentials; without them, he would never have been able to accomplish his work.

How many people have wasted their lives, so often lost to leisure, and so many lost their minds in a flash! How many scholars, deeply rooted in the soil, how many doctors, their time melded with the urgent need for healing! Perhaps those who had something to say only succeeded in making plans, postponing their desires for a miraculous tomorrow that always vanishes!

--- From "Hideout"

Fabre had an unshakable belief in the absolute certainty of his own discoveries.

This was because I observed the object over and over again to the point of being amazed before I asserted its true nature.

This is why Fabre rarely got involved in the controversies surrounding his research.

Fabre was not concerned with controversy, avoided criticism and debate, and never responded to the attacks that surrounded him.

Rather, I kept silent and isolated myself until I felt the research was sufficiently mature and ready to be published.

--- From "Evolution or "Biological Variation""

This is why Fabre always actively denied that he was an entomologist.

And indeed, the word entomologist is often used to misrepresent Fabre.

Fabre called himself a naturalist.

So, biologists.

Biology is, by dictionary definition, a discipline that considers living organisms holistically from all perspectives.

And since nothing in life is isolated, everything is interconnected, and each part in all relationships appears to the observer in countless aspects, one cannot be a true naturalist without being a philosopher.

--- From "Interpretation of Nature"

In portraits of Fabre and in writings describing him, Fabre is simple, precise, and full of innate tenderness.

Fabre used words so aptly that he could reproduce the tiny creatures he observed in living, moving drawings.

Fabre's expressions reach a higher level, his colors become richer, his imagination becomes richer as he seeks to interpret the emotions that move these tiny creatures—the love and fight, the cunning schemes, the pursuit of prey—and the immense drama that accompanies the pain of creation everywhere.

In particular, Fabre shows what profound and inexhaustible resources science can offer poetry, what profound horizons remain unexplored.

The breaking of an egg or pupa is in itself moving.

Because for any living being, “approaching the light is truly an enormous effort.”

--- From "The Epic of Animal Life"

Even the humble grasshopper rubbed its sides and creaked its wings against its shins to express its happiness, and was intoxicated by its own music, which began and ended suddenly “according to the movement of light and shade.”

Every insect has its own rhythm.

Some rhythms are intense, others are barely perceptible.

It is the music of the sun-touched bushes and fallow fields, the music that rises and falls in the waves of joyful life.

Insects are having fun.

They cause noisy festivals and mate endlessly.

Even before they become acquainted with each other, they live fiercely because “the only pleasure of animals is love” and “to love is as good as to die.”

--- From "The Epic of Animal Life"

Dufour's curiosity led him to amass a vast collection, but, as Fabre thought, collecting was "only the dreary contemplation of a vast charnel house, speaking only with the eyes and silent to the mind or imagination," and that the true history of insects should be about their habits, their labors, their battles, their loves, their private and social lives.

Therefore, “we must search everywhere: on the land, under the land, in the water, in the air, under the bark of trees, in the deep forests, in the sands of the desert, and even inside the bodies of animals.”

--- From "Parallel Universe"

Anyone who is suffering from the painful problem of population decline should listen to the lesson of the horned dung beetle.

“They habitually reproduced in times of plenty, often producing only one offspring in times of scarcity, imitating urban artisans who had the means to survive, or the middle classes who limited their offspring to avoid resource scarcity as the cost of satisfying more and more needs grew.”

Despite all the requests addressed to Fabre, he only thought about “the work he loved in the field of natural history.”

Fabre feared that he would lose precious time by “compromising this labor which he felt was pointless” with the research he had already begun in preparation for the selection exams and the explorations he was undertaking in Corsica.

Fabre was busy with his first original research, which he was preparing for his doctorate in natural sciences.

--- From "In Avignon"

Fabre, who observed people as well as animals, looked at the emperor quietly.

The “quite simple” emperor, who rarely showed emotion, exchanged a few words with Fabre, his eyes half-closed.

Fabre watched as “large beetle-like attendants with café-au-lait colored wings came and went, wearing breeches and silver-buckled shoes, and moving with a ceremonial gait.”

Fabre already sighed in regret.

It was boring.

It was terribly painful, and no matter what happened in the world, I never wanted to repeat that experience again.

--- From "In Avignon"

Fabre was able to fully display his talent because it belonged entirely to himself.

For a scholar, explorer, and outdoor observer like Fabre, freedom and leisure were more than just essentials; without them, he would never have been able to accomplish his work.

How many people have wasted their lives, so often lost to leisure, and so many lost their minds in a flash! How many scholars, deeply rooted in the soil, how many doctors, their time melded with the urgent need for healing! Perhaps those who had something to say only succeeded in making plans, postponing their desires for a miraculous tomorrow that always vanishes!

--- From "Hideout"

Fabre had an unshakable belief in the absolute certainty of his own discoveries.

This was because I observed the object over and over again to the point of being amazed before I asserted its true nature.

This is why Fabre rarely got involved in the controversies surrounding his research.

Fabre was not concerned with controversy, avoided criticism and debate, and never responded to the attacks that surrounded him.

Rather, I kept silent and isolated myself until I felt the research was sufficiently mature and ready to be published.

--- From "Evolution or "Biological Variation""

This is why Fabre always actively denied that he was an entomologist.

And indeed, the word entomologist is often used to misrepresent Fabre.

Fabre called himself a naturalist.

So, biologists.

Biology is, by dictionary definition, a discipline that considers living organisms holistically from all perspectives.

And since nothing in life is isolated, everything is interconnected, and each part in all relationships appears to the observer in countless aspects, one cannot be a true naturalist without being a philosopher.

--- From "Interpretation of Nature"

In portraits of Fabre and in writings describing him, Fabre is simple, precise, and full of innate tenderness.

Fabre used words so aptly that he could reproduce the tiny creatures he observed in living, moving drawings.

Fabre's expressions reach a higher level, his colors become richer, his imagination becomes richer as he seeks to interpret the emotions that move these tiny creatures—the love and fight, the cunning schemes, the pursuit of prey—and the immense drama that accompanies the pain of creation everywhere.

In particular, Fabre shows what profound and inexhaustible resources science can offer poetry, what profound horizons remain unexplored.

The breaking of an egg or pupa is in itself moving.

Because for any living being, “approaching the light is truly an enormous effort.”

--- From "The Epic of Animal Life"

Even the humble grasshopper rubbed its sides and creaked its wings against its shins to express its happiness, and was intoxicated by its own music, which began and ended suddenly “according to the movement of light and shade.”

Every insect has its own rhythm.

Some rhythms are intense, others are barely perceptible.

It is the music of the sun-touched bushes and fallow fields, the music that rises and falls in the waves of joyful life.

Insects are having fun.

They cause noisy festivals and mate endlessly.

Even before they become acquainted with each other, they live fiercely because “the only pleasure of animals is love” and “to love is as good as to die.”

--- From "The Epic of Animal Life"

Dufour's curiosity led him to amass a vast collection, but, as Fabre thought, collecting was "only the dreary contemplation of a vast charnel house, speaking only with the eyes and silent to the mind or imagination," and that the true history of insects should be about their habits, their labors, their battles, their loves, their private and social lives.

Therefore, “we must search everywhere: on the land, under the land, in the water, in the air, under the bark of trees, in the deep forests, in the sands of the desert, and even inside the bodies of animals.”

--- From "Parallel Universe"

Anyone who is suffering from the painful problem of population decline should listen to the lesson of the horned dung beetle.

“They habitually reproduced in times of plenty, often producing only one offspring in times of scarcity, imitating urban artisans who had the means to survive, or the middle classes who limited their offspring to avoid resource scarcity as the cost of satisfying more and more needs grew.”

--- From "The Last Years in Serinyan"

Publisher's Review

1.

The only book that allows you to understand Fabre's spirit accurately and richly.

─ A vivid portrayal of Fabre's life and work, which are like a 'scripture of nature.'

─ The life of a scientist who shone with his own light for a long time.

About 110 years have passed since Fabre passed away.

The fact that even after so long, this book has been published in South Korea, and that many people still praise Fabre, shows that his spirit and achievements are still alive and well.

Fabre, who was always cautious about talking about his life even while he was alive due to his taciturn yet stubborn personality, kept silent about rumors for a long time.

In the summer of 1907, the author of this book, Georges Victor Le Gros, who visited Fabre's home and laboratory, 'Armas', with his wife and became his disciple, felt the need to correct the public's misunderstandings about Fabre and began working on this book.

He made generous use of Fabre's manuscripts and correspondence, as well as all the family records provided by his brother, Frédéric Fabre.

Thanks to this, this book has been cited as a major reference work on Fabre both domestically and internationally even after his death.

Every sentence in the book was personally reviewed by Fabre, and the preface he wrote himself reveals the truth of this story.

Fabre, who spent most of his life uncovering the wonders of life, lived a life different from that of the scientists we are familiar with.

Rather than developing theories while enjoying the authority and fame of academia, he devoted his life to educating his students and conducting his own independent research together with them.

He wandered through the fields and mountains, experiencing nature with his whole body, and did not easily react to the voices of others who talked about him.

The fact that Fabre's conclusions, based solely on his own observations and experiences and based solely on evidence, were actually close to the truth, gives us a sense of his remarkable insight.

In this book, we hear the most profound and vivid story about Fabre, who was extremely cautious about appearing in front of others, as well as stories about animals, plants, and nature that were decisive moments in his life.

Thanks to the faithful quotation of key parts of Fabre's work, we can also get a glimpse of his beautiful sentences.

The life of Jean-Henri Fabre, loved across time, space, and age, still inspires us.

His attitude of observing life, which he cannot understand, with awe and tenacity, without making hasty judgments, and his way of living uprightly under the values given by nature rather than by fame and power, not only evokes his achievements as a natural scientist, but also his respect as a human being.

Therefore, not a single line of the reviews in this book was written without Fabre's consent, and most of them can be seen as directly reflecting Fabre's spirit.

I tried to let Fabre speak as much as possible.

Didn't Fabre already depict "the life of a solitary student" in several chapters of "Fabre's Insect Book," which chronicles the birth of the naturalist and the development of his own ideas? For the most part, I've only introduced the essential details needed to complete the series of events.

It would be pointless to repeat in the same terms what can be found elsewhere, or to repeat in different or less satisfactory terms what Fabre himself frequently said.

So I put more effort into filling in the gaps he left behind, by listening to Fabre, appealing to his memory, questioning his contemporaries, and occasionally retracing the footsteps of his disciples.

─ From the “Introductory Remarks”

2.

The first observer to see nature differently

─ The science of situations and contexts that go beyond the anatomical understanding of life.

─ Revealing living nature and creating a new cosmic narrative

Fabre devoted more than ten years to writing science textbooks for children.

Natural history textbooks, which had been filled with boring and dry sentences, were reborn with Fabre's perspective.

The friendly and lively sentences made botany a particularly interesting subject, and “the jewel of Fabre’s Plantae, a series without parallel” (p. 115) also appeared during this period.

The story of insects, which are inseparable from plants, cannot be left out of Fabre's life.

Even before Fabre, there were always scholars who studied insects, such as French scientist René Réaumur.

But Réaumur's research was "stuck in a tedious and endless nomenclature" (p. 300), and Fabre "humorously criticized it, trying to avoid making the same mistake" (p. 169). After him came Léon Dufour, a giant of French entomology, but he was interested in too many things other than insects, and failed to fully understand the small but vast insect world that can only be known by being intimately involved with it.

Fabre became convinced of his calling after seeing how incomplete and poorly verified even the observations of Dufour, known as the “elder of entomology,” were (p. 81).

Unlike previous scientists, Fabre, who had observed nature with sensitivity and thoughtfulness for decades, says that life is “determined not by anatomical characteristics but by disposition or type of labor” (p. 205).

Fabre says that most scientists have been unable to truly understand the meaning of life by observing life through a microscope, mechanically classifying species, genera, families, and orders, and inferring abilities by dissecting corpses.

It means that we must look at life within the context of each individual's situation.

This conclusion of Fabre's is only now reaching us with a resonance in the developed bioethics and botanical sciences.

Perhaps, due to our history of human-centered measurement of animal intelligence and behavior, plant physiology, etc., we have become less and less able to appreciate the wonders of life.

Author Le Gros says:

“It will certainly be a long time before a new Fabre appears in the world.” (p. 307)

Do we really have an environment today where a new Fabre can emerge?

Fabre's innate temperament, his exposure to the culture of science, his encyclopedic knowledge, and his profound understanding of the educational curriculum, which he constantly updated through nearly a decade of writing textbooks, allowed him to delve deeply into his research without limit.

Moreover, Fabre's ability as a great observer to notice the spectacle created by small creatures, to understand their habits, and to perceive them as "a mysterious context connected to the vast universe" (p. 157) is something that cannot be achieved through specialized knowledge alone.

The true skill and talent of observation is “an ever-awake intelligence” (p. 157).

“The desire to tirelessly immerse oneself until one reaches the truth” (p. 157) has firmly supported his life and continues to resonate with the world to this day.

In conclusion, the structure tells us nothing about ability.

The agency does not explain its functions.

Let the experts be distracted by their lenses and microscopes.

Perhaps they will leisurely recount a vast amount of detail about this or that thing, species, genus, family, or order.

No, perhaps we could conduct subtle research and spend countless pages detailing subtle variations without even fully understanding the problem.

You might miss out on what's truly wonderful.

… … A Provençal singer who boasts of the intuition that is the privilege of genius once expressed this thought in beautiful lyrics.

Oh! Fools with scalpels

Looking for death, they think they know

The virtues of bees and the secrets of the hive

─ From Chapter 8, “The Miracle of Instinct”

3.

What choices have great scientists made in life?

─ Providing equal education to workers, tenant farmers, and women

─ A question posed by a life ripe with the world

Fabre has a surprising career.

It is exactly one year of city council activity.

His interest was not in winning power through factional strife, but in a better future and a more developed humanity.

Unlike worldly people who are preoccupied with maintaining their dignity, he worked and worked solely for the sake of learning.

He believed that learning opportunities, which were more important to him than anything else, should be equal, so he provided lectures without discrimination to workers, tenant farmers, and women.

For him, nature was a place of learning for all people around the world.

But as Fabre's fame grew, so did the envy and jealousy directed at him.

People were displeased with Fabre, who drew evidence solely from observation rather than from the authoritative theories of the academic world and acted independently, and called him a “dissident” (p. 105) and “a heretic and a disgrace” (p. 106) for his actions as an egalitarian educator teaching science to girls.

Overcome with disgust, Fabre retires to Orange to distance himself from people.

Fabre settled down in search of his own “Eden” (p. 140).

How chaotic life is, how even scientists, who have presented irrefutable evidence based on observation, have been oppressed by this absurd world, how they have been able to continue their observations despite the help they receive from those around them, what choices and foregoes in life have great observers made.

These impressions and questions that inevitably arise while reading the book allow readers to come up with their own answers about nature and the world.

As Henri Bergson, who contributed to this book, said, “Only intuition can tell us what life truly is.” (p. 158) This can also be applied to understanding this world full of life.

This is why Fabre's life and works, which brought to life on this earth the value that only a living, not a dead, discipline can provide through the act of observation, can be boldly called "the scriptures of nature" (p. 352).

I hope that this book, filled with Fabre's words and life, will become a hopeful message about the coexistence of nature and humanity, and that "a world filled with miracles and poetry" (p. 31) will be revealed to all.

Fabre asserted the continuity of progress.

I believed in a better, less brutal future, a more perfect humanity governed by more harmonious and less brutal norms.

… … He looked at the simplest creatures with the most amazing perspective.

The body of a very insignificant insect suddenly became a transcendental secret, revealing the abyss of the human soul or giving a glimpse of the stars.

Although Fabre's research contradicts evolutionist theory, it concludes with the same instructive conclusion: all creation moves slowly and ceaselessly toward gradual progress.

─ From “Evolution or “Theory of Biological Variation””

The only book that allows you to understand Fabre's spirit accurately and richly.

─ A vivid portrayal of Fabre's life and work, which are like a 'scripture of nature.'

─ The life of a scientist who shone with his own light for a long time.

About 110 years have passed since Fabre passed away.

The fact that even after so long, this book has been published in South Korea, and that many people still praise Fabre, shows that his spirit and achievements are still alive and well.

Fabre, who was always cautious about talking about his life even while he was alive due to his taciturn yet stubborn personality, kept silent about rumors for a long time.

In the summer of 1907, the author of this book, Georges Victor Le Gros, who visited Fabre's home and laboratory, 'Armas', with his wife and became his disciple, felt the need to correct the public's misunderstandings about Fabre and began working on this book.

He made generous use of Fabre's manuscripts and correspondence, as well as all the family records provided by his brother, Frédéric Fabre.

Thanks to this, this book has been cited as a major reference work on Fabre both domestically and internationally even after his death.

Every sentence in the book was personally reviewed by Fabre, and the preface he wrote himself reveals the truth of this story.

Fabre, who spent most of his life uncovering the wonders of life, lived a life different from that of the scientists we are familiar with.

Rather than developing theories while enjoying the authority and fame of academia, he devoted his life to educating his students and conducting his own independent research together with them.

He wandered through the fields and mountains, experiencing nature with his whole body, and did not easily react to the voices of others who talked about him.

The fact that Fabre's conclusions, based solely on his own observations and experiences and based solely on evidence, were actually close to the truth, gives us a sense of his remarkable insight.

In this book, we hear the most profound and vivid story about Fabre, who was extremely cautious about appearing in front of others, as well as stories about animals, plants, and nature that were decisive moments in his life.

Thanks to the faithful quotation of key parts of Fabre's work, we can also get a glimpse of his beautiful sentences.

The life of Jean-Henri Fabre, loved across time, space, and age, still inspires us.

His attitude of observing life, which he cannot understand, with awe and tenacity, without making hasty judgments, and his way of living uprightly under the values given by nature rather than by fame and power, not only evokes his achievements as a natural scientist, but also his respect as a human being.

Therefore, not a single line of the reviews in this book was written without Fabre's consent, and most of them can be seen as directly reflecting Fabre's spirit.

I tried to let Fabre speak as much as possible.

Didn't Fabre already depict "the life of a solitary student" in several chapters of "Fabre's Insect Book," which chronicles the birth of the naturalist and the development of his own ideas? For the most part, I've only introduced the essential details needed to complete the series of events.

It would be pointless to repeat in the same terms what can be found elsewhere, or to repeat in different or less satisfactory terms what Fabre himself frequently said.

So I put more effort into filling in the gaps he left behind, by listening to Fabre, appealing to his memory, questioning his contemporaries, and occasionally retracing the footsteps of his disciples.

─ From the “Introductory Remarks”

2.

The first observer to see nature differently

─ The science of situations and contexts that go beyond the anatomical understanding of life.

─ Revealing living nature and creating a new cosmic narrative

Fabre devoted more than ten years to writing science textbooks for children.

Natural history textbooks, which had been filled with boring and dry sentences, were reborn with Fabre's perspective.

The friendly and lively sentences made botany a particularly interesting subject, and “the jewel of Fabre’s Plantae, a series without parallel” (p. 115) also appeared during this period.

The story of insects, which are inseparable from plants, cannot be left out of Fabre's life.

Even before Fabre, there were always scholars who studied insects, such as French scientist René Réaumur.

But Réaumur's research was "stuck in a tedious and endless nomenclature" (p. 300), and Fabre "humorously criticized it, trying to avoid making the same mistake" (p. 169). After him came Léon Dufour, a giant of French entomology, but he was interested in too many things other than insects, and failed to fully understand the small but vast insect world that can only be known by being intimately involved with it.

Fabre became convinced of his calling after seeing how incomplete and poorly verified even the observations of Dufour, known as the “elder of entomology,” were (p. 81).

Unlike previous scientists, Fabre, who had observed nature with sensitivity and thoughtfulness for decades, says that life is “determined not by anatomical characteristics but by disposition or type of labor” (p. 205).

Fabre says that most scientists have been unable to truly understand the meaning of life by observing life through a microscope, mechanically classifying species, genera, families, and orders, and inferring abilities by dissecting corpses.

It means that we must look at life within the context of each individual's situation.

This conclusion of Fabre's is only now reaching us with a resonance in the developed bioethics and botanical sciences.

Perhaps, due to our history of human-centered measurement of animal intelligence and behavior, plant physiology, etc., we have become less and less able to appreciate the wonders of life.

Author Le Gros says:

“It will certainly be a long time before a new Fabre appears in the world.” (p. 307)

Do we really have an environment today where a new Fabre can emerge?

Fabre's innate temperament, his exposure to the culture of science, his encyclopedic knowledge, and his profound understanding of the educational curriculum, which he constantly updated through nearly a decade of writing textbooks, allowed him to delve deeply into his research without limit.

Moreover, Fabre's ability as a great observer to notice the spectacle created by small creatures, to understand their habits, and to perceive them as "a mysterious context connected to the vast universe" (p. 157) is something that cannot be achieved through specialized knowledge alone.

The true skill and talent of observation is “an ever-awake intelligence” (p. 157).

“The desire to tirelessly immerse oneself until one reaches the truth” (p. 157) has firmly supported his life and continues to resonate with the world to this day.

In conclusion, the structure tells us nothing about ability.

The agency does not explain its functions.

Let the experts be distracted by their lenses and microscopes.

Perhaps they will leisurely recount a vast amount of detail about this or that thing, species, genus, family, or order.

No, perhaps we could conduct subtle research and spend countless pages detailing subtle variations without even fully understanding the problem.

You might miss out on what's truly wonderful.

… … A Provençal singer who boasts of the intuition that is the privilege of genius once expressed this thought in beautiful lyrics.

Oh! Fools with scalpels

Looking for death, they think they know

The virtues of bees and the secrets of the hive

─ From Chapter 8, “The Miracle of Instinct”

3.

What choices have great scientists made in life?

─ Providing equal education to workers, tenant farmers, and women

─ A question posed by a life ripe with the world

Fabre has a surprising career.

It is exactly one year of city council activity.

His interest was not in winning power through factional strife, but in a better future and a more developed humanity.

Unlike worldly people who are preoccupied with maintaining their dignity, he worked and worked solely for the sake of learning.

He believed that learning opportunities, which were more important to him than anything else, should be equal, so he provided lectures without discrimination to workers, tenant farmers, and women.

For him, nature was a place of learning for all people around the world.

But as Fabre's fame grew, so did the envy and jealousy directed at him.

People were displeased with Fabre, who drew evidence solely from observation rather than from the authoritative theories of the academic world and acted independently, and called him a “dissident” (p. 105) and “a heretic and a disgrace” (p. 106) for his actions as an egalitarian educator teaching science to girls.

Overcome with disgust, Fabre retires to Orange to distance himself from people.

Fabre settled down in search of his own “Eden” (p. 140).

How chaotic life is, how even scientists, who have presented irrefutable evidence based on observation, have been oppressed by this absurd world, how they have been able to continue their observations despite the help they receive from those around them, what choices and foregoes in life have great observers made.

These impressions and questions that inevitably arise while reading the book allow readers to come up with their own answers about nature and the world.

As Henri Bergson, who contributed to this book, said, “Only intuition can tell us what life truly is.” (p. 158) This can also be applied to understanding this world full of life.

This is why Fabre's life and works, which brought to life on this earth the value that only a living, not a dead, discipline can provide through the act of observation, can be boldly called "the scriptures of nature" (p. 352).

I hope that this book, filled with Fabre's words and life, will become a hopeful message about the coexistence of nature and humanity, and that "a world filled with miracles and poetry" (p. 31) will be revealed to all.

Fabre asserted the continuity of progress.

I believed in a better, less brutal future, a more perfect humanity governed by more harmonious and less brutal norms.

… … He looked at the simplest creatures with the most amazing perspective.

The body of a very insignificant insect suddenly became a transcendental secret, revealing the abyss of the human soul or giving a glimpse of the stars.

Although Fabre's research contradicts evolutionist theory, it concludes with the same instructive conclusion: all creation moves slowly and ceaselessly toward gradual progress.

─ From “Evolution or “Theory of Biological Variation””

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 16, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 384 pages | 496g | 140*210*18mm

- ISBN13: 9791170872429

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)