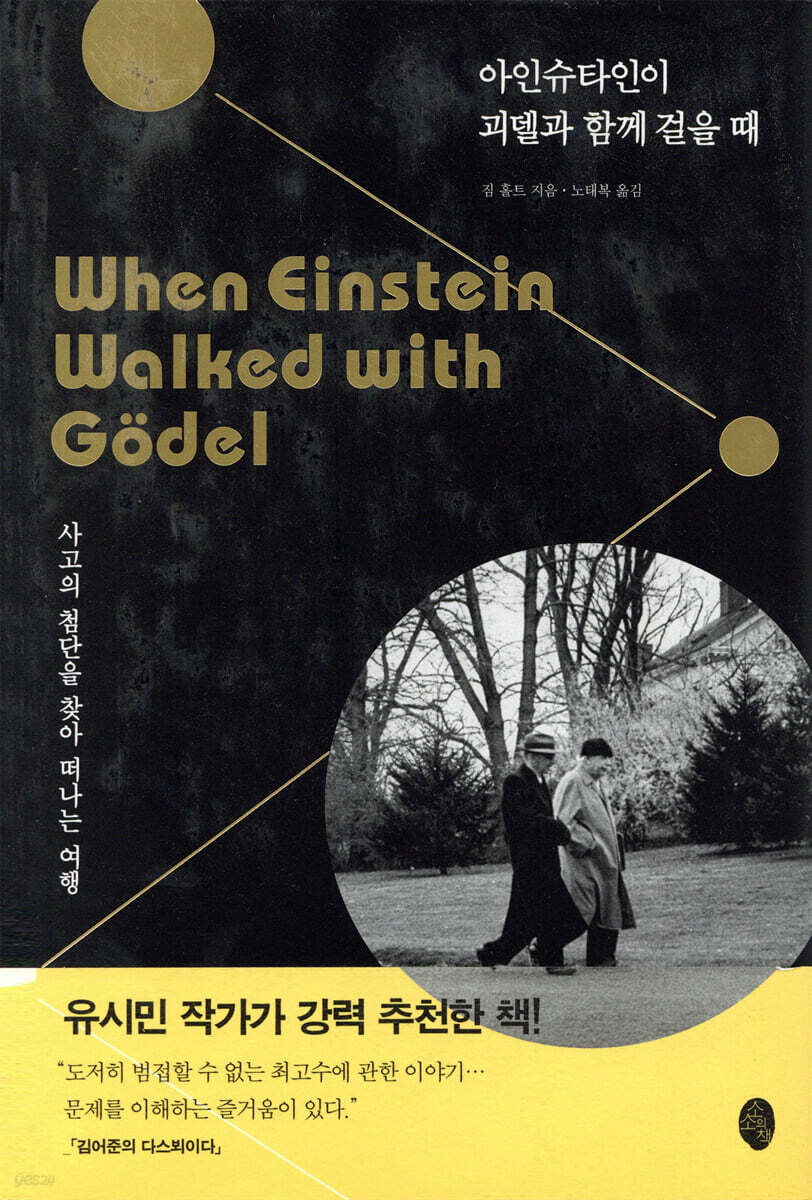

When Einstein walked with Gödel

|

Description

Book Introduction

Einstein was friendly and liked to laugh What kind of conversations would Gödel, who was always gloomy, lonely, and pessimistic, have had? Talk about profound concepts as if they were cocktail party chatter, A peek into the dramatic lives of thinkers who shared a sense of intellectual isolation! Ten years after Einstein, the world's most famous figure and recognizable from afar for his messy hair and baggy pants with suspenders, arrived at Princeton, he had a walking companion. He was twenty-seven years younger than Kurt Gödel, wearing a white linen suit and bowler hat. Unlike Einstein, who was usually sociable and humorous, Gödel was always gloomy, lonely, and pessimistic. While Einstein loved Beethoven and Mozart and indulged in rich German cuisine, Gödel loved Walt Disney movies and barely survived on a diet of invalids, baby food, and laxatives. How could two such different people have such lively conversations in German on their morning commutes to the lab and on their afternoon commutes home? Gödel wasn't widely known at the time, but Einstein considered him a comrade who, like himself, had independently developed revolutionary ideas. It is said that the two did not want to talk to anyone else and wanted to talk only among themselves. Both Gödel and Einstein believed that the world was rationally organized, independent of our individual perceptions, and ultimately comprehensible to humans. The two people who shared a sense of intellectual isolation found solace in each other's company. From the human side of brilliant scientists to Einstein's theory of relativity to string theory, it distills the most beautiful yet profound concepts to their essence and presents them in an accessible manner, allowing readers to savor the depth and power of thought conveyed through the writing, as well as the pure joy of insight. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Part 1: Moving Images of Eternity

1.

When Einstein walked with Gödel

2.

Is time just a giant illusion?

Part 2: Three Worlds Where Numbers Are Active

3.

Number Man

4.

The Riemann Zeta Conjecture and the Laugh of the Ultimate Winner

5.

Sir Francis Galton, father of statistics and eugenics

Part 3 Mathematics, Pure and Impure

6.

A Mathematician's Romance

7.

Avatars of Advanced Mathematics

8.

Benoit Mandelbrot and the Discovery of Fractals

Part 4 Higher Dimensions, Abstract Maps

9.

geometric creations

10.

comedy of colors

Part 5: Infinity, Great Infinity and Small Infinity

11.

Infinite Vision

12.

Infinite Worship

13.

The dangerous idea of infinite space

Part 6: Heroism, Tragedy, and the Computer Age

14.

Controversy surrounding Ada

15.

The Life, Logic, and Death of Alan Turing

16.

Dr. Strangelove creates a 'thinking machine'

17.

Smarter, happier, more productive

Part 7: Revisiting the Universe

18.

String Theory Wars: Is Beauty Truth?

19.

Einstein, 'Ghostly Action', and the Reality of Space

20.

How Does the Universe End? 329

Part 8: Short but Meaningful Thoughts

Humans, beings that are both very small and very large at the same time

impending doom

Is death bad?

Mirror Wars

Astrology and the Problem of Compartmentation

Gödel questions the U.S. Constitution

Law of Least Action

Emmy Noether's Beautiful Theorem

Is logic coercive?

Newcomb's Problem and the Paradox of Choice

The right not to exist

Can't anyone understand Heisenberg correctly?

Overconfidence and the Monty Hall Problem

cruel naming rules

Heart of Stone

Part 9: God, Saints, Truth, and Nonsense

21.

Dawkins and Shin

22.

On moral adults

23.

Truth and Reference

24.

Say anything

Recommended books

Acknowledgements

Search

Part 1: Moving Images of Eternity

1.

When Einstein walked with Gödel

2.

Is time just a giant illusion?

Part 2: Three Worlds Where Numbers Are Active

3.

Number Man

4.

The Riemann Zeta Conjecture and the Laugh of the Ultimate Winner

5.

Sir Francis Galton, father of statistics and eugenics

Part 3 Mathematics, Pure and Impure

6.

A Mathematician's Romance

7.

Avatars of Advanced Mathematics

8.

Benoit Mandelbrot and the Discovery of Fractals

Part 4 Higher Dimensions, Abstract Maps

9.

geometric creations

10.

comedy of colors

Part 5: Infinity, Great Infinity and Small Infinity

11.

Infinite Vision

12.

Infinite Worship

13.

The dangerous idea of infinite space

Part 6: Heroism, Tragedy, and the Computer Age

14.

Controversy surrounding Ada

15.

The Life, Logic, and Death of Alan Turing

16.

Dr. Strangelove creates a 'thinking machine'

17.

Smarter, happier, more productive

Part 7: Revisiting the Universe

18.

String Theory Wars: Is Beauty Truth?

19.

Einstein, 'Ghostly Action', and the Reality of Space

20.

How Does the Universe End? 329

Part 8: Short but Meaningful Thoughts

Humans, beings that are both very small and very large at the same time

impending doom

Is death bad?

Mirror Wars

Astrology and the Problem of Compartmentation

Gödel questions the U.S. Constitution

Law of Least Action

Emmy Noether's Beautiful Theorem

Is logic coercive?

Newcomb's Problem and the Paradox of Choice

The right not to exist

Can't anyone understand Heisenberg correctly?

Overconfidence and the Monty Hall Problem

cruel naming rules

Heart of Stone

Part 9: God, Saints, Truth, and Nonsense

21.

Dawkins and Shin

22.

On moral adults

23.

Truth and Reference

24.

Say anything

Recommended books

Acknowledgements

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

While other members of the institute were uncomfortable and embarrassed by this gloomy logician, Einstein said to people:

He said that the reason he came to the lab was 'just to have the privilege of walking home with Kurt Gödel.'

Perhaps the reason he said that was because Gödel was not intimidated by Einstein's fame and boldly presented counterarguments.

Freeman Dyson, a physicist who worked with me at the Institute for Advanced Study, said:

“Dr. Gödel was… the only one of our colleagues who walked and talked with Dr. Einstein on an equal footing.” Einstein and Gödel seemed to stand on a higher plane than the rest of humanity, but it was also true that, as Einstein said, they ended up as “museum pieces.”

Einstein did not accept the quantum theory of Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg.

Gödel believed that the abstract concepts of mathematics were every bit as real as tables and chairs, a view that philosophers laughed off as naive.

Both Gödel and Einstein believed that the world was rationally organized, independent of our individual perceptions, and ultimately comprehensible to humans.

The two, who shared a sense of intellectual isolation, found solace in each other's company.

Someone else at the lab said:

“Neither of them wanted to talk to anyone else.

“They wanted to talk only among themselves.” ---p.1.

When Einstein was walking with Gödel

As Einstein discovered, there is no universal 'now'.

Whether two events are simultaneous or not depends on the observer.

Once simultaneity becomes meaningless, the very division of time into 'past', 'present', and 'future' becomes meaningless.

An event judged to be in the past by one observer may still be in the future by another observer.

Therefore, it is clear that the past and the present are equally definite.

In other words, both are ‘reality’.

Instead of the fleeting present, we are left with a vast frozen timescape—a four-dimensional “block universe.”

Here you are being born, there you are celebrating the arrival of the millennium, and there you are dying for a while.

Nothing 'flows' from one event to another.

As the mathematician Hermann Weyl famously said, “The objective world simply exists, it does not occur.”

---p.2.

Is time just a gigantic illusion?

Mandelbrot believed that complex mechanics could be deciphered using the power of computers.

At the time, mathematicians dismissed computers, “shuddering at the very thought that a machine might corrupt the lofty ‘purity’ of mathematics.”

But Mandelbrot was far from a purist, and he ran his new VAX superminicomputer in the basement of Harvard University's Science Center.

Using the computer's graphics capabilities as a kind of microscope, he began to investigate the geometric forms generated by a very simple formula (the only formula that appears in his memoirs, by the way).

As the computer revealed the shape in increasingly more detail, what he saw was entirely unexpected.

It was a wondrous world of beetle-like blobs, tendrils, swirls, typical seahorses, dragon-like creatures, all connected by fluffy lines, surrounded by exploding buds.

At first, I thought such geometric chaos was due to equipment defects.

But as the computer zoomed in on the shapes, the patterns became more precise (and more fantastical).

Indeed, the pattern contained infinite copies of itself on ever smaller scales, each copy bearing its own Rococo decorations.

This is the world called the 'Mandelbrot set'.

---p.8.

During the discovery of fractals by Benoit Mandelbrot

After examining the German Navy's Enigma, Turing quickly discovered one weakness.

Encrypted naval messages frequently contained formal phrases like 'WETTER FUER DIE NACHT' (Weather at night), so it was not clear whether these could provide a clue.

Turing realized that such 'cheat sheets' could be used to generate logical links, each of which would correspond to one of billions of possible Enigma settings.

When one of those links reached a contradiction—an internal inconsistency in the cryptographic assumptions—it was possible to rule out billions of corresponding configurations.

The problem is now reduced to checking millions of logical connections.

This was also daunting, but certainly not impossible.

Turing set out to design a machine that would automate logical consistency checking.

It was a machine that would eliminate those contradictory links quickly enough for cryptographers to figure out the Enigma settings of the day before the information became obsolete.

The result was a machine the size of several refrigerators, consisting of dozens of rotating cylinders (mimicking the Enigma wheel) and enormous coils of colorful wire.

When activated, the machine would check the logical connections between the relay switches one by one, making a sound like the rattling of thousands of knitting needles.

In honor of the previous Polish code-breaking machine that made an ominous clattering sound, the Bletchley people called it Bombe.

---p.15.

The Life, Logic, and Death of Alan Turing

It seems that achieving great altruistic achievements requires not only the necessary technical and organizational skills, but also exceptional creativity.

Florence Nightingale, who devoted her life to caring for the wounded in war, did tremendous good (though her reforms, by reducing the loss of life in war, may have made future wars more likely).

But the Nightingale was not, as Strachey exposed to the early twentieth century, a kind and self-sacrificing angel of mercy.

She was a self-centered woman who was quick to anger, sarcastic, sarcastic, and had an unyielding, stubborn will.

You could say he had the temperament of an artist.

The British writer Evelyn Waugh once said:

“Humility is not a virtue that favors the artist.

Pride, competitiveness, greed, malice—all these are repulsive qualities—that drive man to create, refine, fix, destroy, and recreate his creation until he has created something that satisfies his pride, his envy, and his greed.

In doing so, artists enrich the world more than generous and kind people.

“Even though you may lose your soul in the process, this is the paradox of artistic achievement.”

He said that the reason he came to the lab was 'just to have the privilege of walking home with Kurt Gödel.'

Perhaps the reason he said that was because Gödel was not intimidated by Einstein's fame and boldly presented counterarguments.

Freeman Dyson, a physicist who worked with me at the Institute for Advanced Study, said:

“Dr. Gödel was… the only one of our colleagues who walked and talked with Dr. Einstein on an equal footing.” Einstein and Gödel seemed to stand on a higher plane than the rest of humanity, but it was also true that, as Einstein said, they ended up as “museum pieces.”

Einstein did not accept the quantum theory of Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg.

Gödel believed that the abstract concepts of mathematics were every bit as real as tables and chairs, a view that philosophers laughed off as naive.

Both Gödel and Einstein believed that the world was rationally organized, independent of our individual perceptions, and ultimately comprehensible to humans.

The two, who shared a sense of intellectual isolation, found solace in each other's company.

Someone else at the lab said:

“Neither of them wanted to talk to anyone else.

“They wanted to talk only among themselves.” ---p.1.

When Einstein was walking with Gödel

As Einstein discovered, there is no universal 'now'.

Whether two events are simultaneous or not depends on the observer.

Once simultaneity becomes meaningless, the very division of time into 'past', 'present', and 'future' becomes meaningless.

An event judged to be in the past by one observer may still be in the future by another observer.

Therefore, it is clear that the past and the present are equally definite.

In other words, both are ‘reality’.

Instead of the fleeting present, we are left with a vast frozen timescape—a four-dimensional “block universe.”

Here you are being born, there you are celebrating the arrival of the millennium, and there you are dying for a while.

Nothing 'flows' from one event to another.

As the mathematician Hermann Weyl famously said, “The objective world simply exists, it does not occur.”

---p.2.

Is time just a gigantic illusion?

Mandelbrot believed that complex mechanics could be deciphered using the power of computers.

At the time, mathematicians dismissed computers, “shuddering at the very thought that a machine might corrupt the lofty ‘purity’ of mathematics.”

But Mandelbrot was far from a purist, and he ran his new VAX superminicomputer in the basement of Harvard University's Science Center.

Using the computer's graphics capabilities as a kind of microscope, he began to investigate the geometric forms generated by a very simple formula (the only formula that appears in his memoirs, by the way).

As the computer revealed the shape in increasingly more detail, what he saw was entirely unexpected.

It was a wondrous world of beetle-like blobs, tendrils, swirls, typical seahorses, dragon-like creatures, all connected by fluffy lines, surrounded by exploding buds.

At first, I thought such geometric chaos was due to equipment defects.

But as the computer zoomed in on the shapes, the patterns became more precise (and more fantastical).

Indeed, the pattern contained infinite copies of itself on ever smaller scales, each copy bearing its own Rococo decorations.

This is the world called the 'Mandelbrot set'.

---p.8.

During the discovery of fractals by Benoit Mandelbrot

After examining the German Navy's Enigma, Turing quickly discovered one weakness.

Encrypted naval messages frequently contained formal phrases like 'WETTER FUER DIE NACHT' (Weather at night), so it was not clear whether these could provide a clue.

Turing realized that such 'cheat sheets' could be used to generate logical links, each of which would correspond to one of billions of possible Enigma settings.

When one of those links reached a contradiction—an internal inconsistency in the cryptographic assumptions—it was possible to rule out billions of corresponding configurations.

The problem is now reduced to checking millions of logical connections.

This was also daunting, but certainly not impossible.

Turing set out to design a machine that would automate logical consistency checking.

It was a machine that would eliminate those contradictory links quickly enough for cryptographers to figure out the Enigma settings of the day before the information became obsolete.

The result was a machine the size of several refrigerators, consisting of dozens of rotating cylinders (mimicking the Enigma wheel) and enormous coils of colorful wire.

When activated, the machine would check the logical connections between the relay switches one by one, making a sound like the rattling of thousands of knitting needles.

In honor of the previous Polish code-breaking machine that made an ominous clattering sound, the Bletchley people called it Bombe.

---p.15.

The Life, Logic, and Death of Alan Turing

It seems that achieving great altruistic achievements requires not only the necessary technical and organizational skills, but also exceptional creativity.

Florence Nightingale, who devoted her life to caring for the wounded in war, did tremendous good (though her reforms, by reducing the loss of life in war, may have made future wars more likely).

But the Nightingale was not, as Strachey exposed to the early twentieth century, a kind and self-sacrificing angel of mercy.

She was a self-centered woman who was quick to anger, sarcastic, sarcastic, and had an unyielding, stubborn will.

You could say he had the temperament of an artist.

The British writer Evelyn Waugh once said:

“Humility is not a virtue that favors the artist.

Pride, competitiveness, greed, malice—all these are repulsive qualities—that drive man to create, refine, fix, destroy, and recreate his creation until he has created something that satisfies his pride, his envy, and his greed.

In doing so, artists enrich the world more than generous and kind people.

“Even though you may lose your soul in the process, this is the paradox of artistic achievement.”

---From the text

Publisher's Review

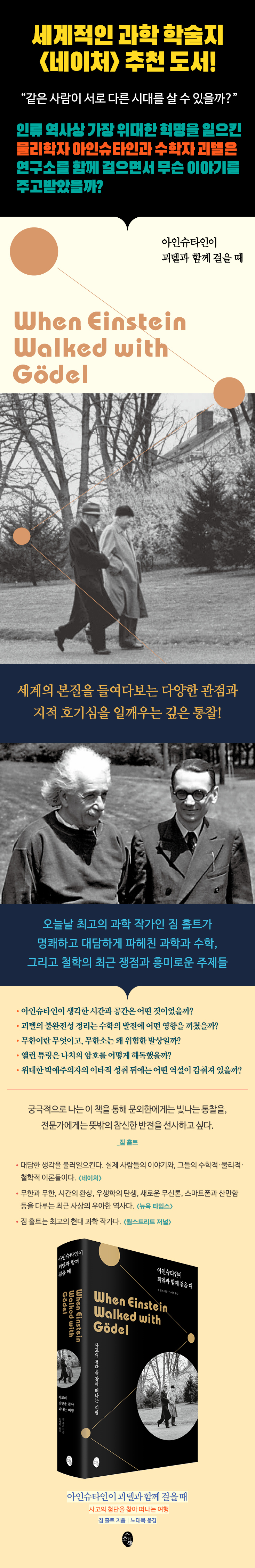

Meet intellectual curiosity, deep insight, and great thinkers!

Recommended Books from World-Class Scientific Journals / Amazon's "Book of the Month"

This book, written by Jim Holt, one of today's leading science writers and philosophers, explores key issues and topics in the history of science, mathematics, and philosophy.

With characteristic clarity and humor, the author delves into the mysteries of quantum mechanics, questions about the foundations of mathematics, and the nature of logic and truth.

It also doesn't miss the human side of famous thinkers we know, from mathematician Emmy Noether to computer pioneer Alan Turing and fractal discoverer Benoît Mandelbrot, as well as thinkers who have been neglected by academia or the public.

In particular, this book not only conveys the most beautiful yet profound concepts, from Einstein's theory of relativity to string theory, in an easy-to-understand manner by distilling them to their essence, but also allows readers to savor the depth and power of the thoughts conveyed in the text, as well as the pure joy of insight.

What did Einstein and Gödel talk about on the road?

“I come to the lab only to have the privilege of walking home with Kurt Gödel.”

Ten years after Einstein, the world's most famous figure and recognizable from afar for his messy hair and baggy pants with suspenders, arrived at Princeton, he had a walking companion.

He was twenty-seven years younger than Kurt Gödel, wearing a white linen suit and bowler hat.

Unlike Einstein, who was usually sociable and humorous, Gödel was always gloomy, lonely, and pessimistic.

While Einstein loved Beethoven and Mozart and indulged in rich German cuisine, Gödel loved Walt Disney movies and barely survived on a diet of invalids, baby food, and laxatives.

How could two such different people have such lively conversations in German on their morning commutes to the lab and on their afternoon commutes home? Gödel wasn't widely known at the time, but Einstein considered him a comrade who, like himself, had independently developed revolutionary ideas.

It is said that the two did not want to talk to anyone else and wanted to talk only among themselves.

Both Gödel and Einstein believed that the world was rationally organized, independent of our individual perceptions, and ultimately comprehensible to humans.

The two people who shared a sense of intellectual isolation found solace in each other's company.

While Einstein overturned our everyday concept of the material world with his theory of relativity, Gödel revolutionized the abstract world of mathematics and is also called the greatest logician since Aristotle.

Talk about profound concepts as if they were cocktail party chatter,

A peek into the dramatic lives of thinkers!

Jim Holt, widely recognized as one of today's leading science writers and philosophers, says that the first thing he kept in mind when publishing his writings of the past 20 years was the depth, power, and sheer beauty of the ideas they convey.

In this book, the author deals with the intellectual achievements that have been most interesting to him, such as Einstein's (special and general) theory of relativity, quantum mechanics, group theory, infinity and infinitesimals, Turing's computability and the 'decision problem', Gödel's incompleteness theorem, prime numbers and the Riemann zeta conjecture, category theory, topology, higher dimensions, fractals, statistical regression analysis and 'bell curves', and the theory of truth, and tries to convey profound concepts to interested people in a refreshing and enjoyable way by exposing only the core of the concepts, as if it were cocktail party chit-chat.

The idea is to provide brilliant insights to laymen and unexpected, novel twists to experts, without being boring at all.

This book also vividly examines the human side of thinkers who achieved great intellectual achievements.

All the ideas in this book unfold alongside the founders of those ideas, who lived very dramatic lives and were flesh and blood.

Often there is an element of absurdity in their lives.

Sir Francis Galton, a Victorian scholar, was not as great as his cousin Charles Darwin, but he was a multitalented man.

He explored uncharted territories through the African bush, pioneered weather forecasting and fingerprint identification, and also discovered statistical concepts that revolutionized scientific methodology.

Galton was a charming and sociable man, though a bit vulgar.

But today he is most famous for an achievement that has made him look decidedly negatively at himself.

Because he is considered the father of eugenics, the science, or perhaps pseudoscience, of 'improving' humanity through selective breeding.

There are also quite a few people who unfortunately passed away.

Évariste Galois, the founder of group theory, was killed by a suspected government spy in a duel defending a woman's honor just before his twenty-first birthday.

Alexander Grothendiecki, hailed as one of the most revolutionary mathematicians of the late 20th century, had a turbulent life.

A fierce advocate of minimalism, he despised money and dressed like a monk.

As a staunch pacifist and anti-war activist, he refused to go to Moscow (the site of that year's International Congress of Mathematicians) to receive the Fields Medal, the highest award in mathematics, in 1966, but the following year he went to North Vietnam and lectured in pure mathematics in the jungle to students who had fled Hanoi to escape American bombing.

A stateless person for most of his life, he was once arrested for knocking out two police officers at a political rally in Avignon, and ended up living as a delusional recluse in the foothills of the Pyrenees, surviving on dandelion soup.

Georg Cantor, the founder of infinity theory and a Jewish mystic, died in a mental hospital.

Ada Lovelace, the goddess of fanatical cyberfeminism, was obsessed with atonement for her father, Lord Byron's debauched life.

Two great Russian mathematicians, Dmitry Yegorov and Pavel Florence, masters of the theory of infinity, were murdered in Stalin's gulags on charges of being adherents of anti-materialist spiritualism.

Kurt Gödel suffered from hallucinations and often spoke darkly of a force at work in the world that “sinks goodness in an instant.”

He persistently refused to eat food, fearing that there was a plot to poison him.

The cause of his death was 'malnutrition and debility' brought on by 'personality disorder'.

Alan Turing, who conceived the concept of the computer, solved the most formidable logic puzzle of his time, and saved countless lives by deciphering the Nazi Enigma code, took his own life by biting into an apple laced with cyanide, for reasons unknown.

Interesting questions and solid intellectual insights built on a philosophical foundation.

Consisting of twenty-four essays and fifteen "short but meaningful thoughts," this book is particularly interesting because it covers a wide range of topics that have been or are still being debated in modern science, mathematics, and philosophy.

In particular, each chapter's theme not only clearly outlines the core of the most common concepts about this world, making it easy to understand, but also raises questions about how we acquire and justify knowledge, and ultimately, how we should live, and closely examines the perspectives of various thinkers on the answers.

Are matter, space, and time infinitely divisible? In the concept of the infinitesimal, is reality continuous, like a vat of syrup, or discrete, like a heap of sand? Why did Einstein oppose quantum mechanics? What relevance do the three scenarios predicting the end of the universe have for us today, and why should we want it to last forever? How did Ada, who couldn't even grasp the most basic of trigonometry, come to be hailed as the inventor of computer programming, the "Wizard of Numbers," and a visionary of technology?

The philosophical debate surrounding pure mathematics and commercialism is also worth noting.

Is pure mathematics merely an elaborate play of formal symbols, performed with pencil and paper, incapable of describing any object, or is it the most ingenious creation of the human mind, a beauty born from the mystery of inner reflection? How do the great mathematicians, who penetrate the eternal realm of abstract forms that transcends the ordinary world we inhabit, navigate through "Platonic" worlds to acquire mathematical knowledge? Why have mathematicians struggled for so long to prove the Riemann zeta hypothesis, the greatest unsolved problem in all of mathematics, and perhaps the most difficult ever conceived by humankind?

The physics community is currently engaged in a string theory war.

It is considered the best and worst of times.

Nearly the entire physics community is working to derive the working equations for string theory, the powerful and mathematically beautiful theory that physicists have long sought, and there is a surge of anticipation that the millennia-old dream of a final theory may soon become reality.

Meanwhile, physicists have been chasing the will-o'-the-wisps of string theory for more than a generation.

Dozens of string theory conferences have been held, hundreds of PhDs have been awarded, and thousands of papers have been written.

Despite all this activity, not a single new, verifiable prediction has emerged.

Not a single theoretical problem was solved, and all sorts of signs and calculations were running wild.

Yet the physics community continues to push string theory with irrational enthusiasm.

By ruthlessly expelling opposing physicists from academia.

Meanwhile, physics was trapped in a paradigm doomed to be barren.

The author also suggests that the equation that beauty equals truth has captivated physicists for most of the past century, but that equation may have led them astray in recent years.

This book deals with ethical aspects and the way of life.

The eugenics programs of Europe and America, driven by the theoretical assumptions of Sir Francis Galton, brutally demonstrate how science can corrupt ethics.

The current reality of how computers are changing our lifestyles leads us to think deeply about the nature of happiness and creative fulfillment.

And the suffering that pervades the world makes us ask what limits there can be to the demands that morality imposes on us.

Beyond this, the author sharply and at times humorously tackles topics that have not only provided great insights but also become important points of contention in the history of modern intellectual thought, crossing the boundaries of various fields, such as the fierce debate over Saul Kripke's designation as the discoverer of a new theory, Richard Dawkins' hypothesis and core argument, and the four-color theorem.

Recommended Books from World-Class Scientific Journals / Amazon's "Book of the Month"

This book, written by Jim Holt, one of today's leading science writers and philosophers, explores key issues and topics in the history of science, mathematics, and philosophy.

With characteristic clarity and humor, the author delves into the mysteries of quantum mechanics, questions about the foundations of mathematics, and the nature of logic and truth.

It also doesn't miss the human side of famous thinkers we know, from mathematician Emmy Noether to computer pioneer Alan Turing and fractal discoverer Benoît Mandelbrot, as well as thinkers who have been neglected by academia or the public.

In particular, this book not only conveys the most beautiful yet profound concepts, from Einstein's theory of relativity to string theory, in an easy-to-understand manner by distilling them to their essence, but also allows readers to savor the depth and power of the thoughts conveyed in the text, as well as the pure joy of insight.

What did Einstein and Gödel talk about on the road?

“I come to the lab only to have the privilege of walking home with Kurt Gödel.”

Ten years after Einstein, the world's most famous figure and recognizable from afar for his messy hair and baggy pants with suspenders, arrived at Princeton, he had a walking companion.

He was twenty-seven years younger than Kurt Gödel, wearing a white linen suit and bowler hat.

Unlike Einstein, who was usually sociable and humorous, Gödel was always gloomy, lonely, and pessimistic.

While Einstein loved Beethoven and Mozart and indulged in rich German cuisine, Gödel loved Walt Disney movies and barely survived on a diet of invalids, baby food, and laxatives.

How could two such different people have such lively conversations in German on their morning commutes to the lab and on their afternoon commutes home? Gödel wasn't widely known at the time, but Einstein considered him a comrade who, like himself, had independently developed revolutionary ideas.

It is said that the two did not want to talk to anyone else and wanted to talk only among themselves.

Both Gödel and Einstein believed that the world was rationally organized, independent of our individual perceptions, and ultimately comprehensible to humans.

The two people who shared a sense of intellectual isolation found solace in each other's company.

While Einstein overturned our everyday concept of the material world with his theory of relativity, Gödel revolutionized the abstract world of mathematics and is also called the greatest logician since Aristotle.

Talk about profound concepts as if they were cocktail party chatter,

A peek into the dramatic lives of thinkers!

Jim Holt, widely recognized as one of today's leading science writers and philosophers, says that the first thing he kept in mind when publishing his writings of the past 20 years was the depth, power, and sheer beauty of the ideas they convey.

In this book, the author deals with the intellectual achievements that have been most interesting to him, such as Einstein's (special and general) theory of relativity, quantum mechanics, group theory, infinity and infinitesimals, Turing's computability and the 'decision problem', Gödel's incompleteness theorem, prime numbers and the Riemann zeta conjecture, category theory, topology, higher dimensions, fractals, statistical regression analysis and 'bell curves', and the theory of truth, and tries to convey profound concepts to interested people in a refreshing and enjoyable way by exposing only the core of the concepts, as if it were cocktail party chit-chat.

The idea is to provide brilliant insights to laymen and unexpected, novel twists to experts, without being boring at all.

This book also vividly examines the human side of thinkers who achieved great intellectual achievements.

All the ideas in this book unfold alongside the founders of those ideas, who lived very dramatic lives and were flesh and blood.

Often there is an element of absurdity in their lives.

Sir Francis Galton, a Victorian scholar, was not as great as his cousin Charles Darwin, but he was a multitalented man.

He explored uncharted territories through the African bush, pioneered weather forecasting and fingerprint identification, and also discovered statistical concepts that revolutionized scientific methodology.

Galton was a charming and sociable man, though a bit vulgar.

But today he is most famous for an achievement that has made him look decidedly negatively at himself.

Because he is considered the father of eugenics, the science, or perhaps pseudoscience, of 'improving' humanity through selective breeding.

There are also quite a few people who unfortunately passed away.

Évariste Galois, the founder of group theory, was killed by a suspected government spy in a duel defending a woman's honor just before his twenty-first birthday.

Alexander Grothendiecki, hailed as one of the most revolutionary mathematicians of the late 20th century, had a turbulent life.

A fierce advocate of minimalism, he despised money and dressed like a monk.

As a staunch pacifist and anti-war activist, he refused to go to Moscow (the site of that year's International Congress of Mathematicians) to receive the Fields Medal, the highest award in mathematics, in 1966, but the following year he went to North Vietnam and lectured in pure mathematics in the jungle to students who had fled Hanoi to escape American bombing.

A stateless person for most of his life, he was once arrested for knocking out two police officers at a political rally in Avignon, and ended up living as a delusional recluse in the foothills of the Pyrenees, surviving on dandelion soup.

Georg Cantor, the founder of infinity theory and a Jewish mystic, died in a mental hospital.

Ada Lovelace, the goddess of fanatical cyberfeminism, was obsessed with atonement for her father, Lord Byron's debauched life.

Two great Russian mathematicians, Dmitry Yegorov and Pavel Florence, masters of the theory of infinity, were murdered in Stalin's gulags on charges of being adherents of anti-materialist spiritualism.

Kurt Gödel suffered from hallucinations and often spoke darkly of a force at work in the world that “sinks goodness in an instant.”

He persistently refused to eat food, fearing that there was a plot to poison him.

The cause of his death was 'malnutrition and debility' brought on by 'personality disorder'.

Alan Turing, who conceived the concept of the computer, solved the most formidable logic puzzle of his time, and saved countless lives by deciphering the Nazi Enigma code, took his own life by biting into an apple laced with cyanide, for reasons unknown.

Interesting questions and solid intellectual insights built on a philosophical foundation.

Consisting of twenty-four essays and fifteen "short but meaningful thoughts," this book is particularly interesting because it covers a wide range of topics that have been or are still being debated in modern science, mathematics, and philosophy.

In particular, each chapter's theme not only clearly outlines the core of the most common concepts about this world, making it easy to understand, but also raises questions about how we acquire and justify knowledge, and ultimately, how we should live, and closely examines the perspectives of various thinkers on the answers.

Are matter, space, and time infinitely divisible? In the concept of the infinitesimal, is reality continuous, like a vat of syrup, or discrete, like a heap of sand? Why did Einstein oppose quantum mechanics? What relevance do the three scenarios predicting the end of the universe have for us today, and why should we want it to last forever? How did Ada, who couldn't even grasp the most basic of trigonometry, come to be hailed as the inventor of computer programming, the "Wizard of Numbers," and a visionary of technology?

The philosophical debate surrounding pure mathematics and commercialism is also worth noting.

Is pure mathematics merely an elaborate play of formal symbols, performed with pencil and paper, incapable of describing any object, or is it the most ingenious creation of the human mind, a beauty born from the mystery of inner reflection? How do the great mathematicians, who penetrate the eternal realm of abstract forms that transcends the ordinary world we inhabit, navigate through "Platonic" worlds to acquire mathematical knowledge? Why have mathematicians struggled for so long to prove the Riemann zeta hypothesis, the greatest unsolved problem in all of mathematics, and perhaps the most difficult ever conceived by humankind?

The physics community is currently engaged in a string theory war.

It is considered the best and worst of times.

Nearly the entire physics community is working to derive the working equations for string theory, the powerful and mathematically beautiful theory that physicists have long sought, and there is a surge of anticipation that the millennia-old dream of a final theory may soon become reality.

Meanwhile, physicists have been chasing the will-o'-the-wisps of string theory for more than a generation.

Dozens of string theory conferences have been held, hundreds of PhDs have been awarded, and thousands of papers have been written.

Despite all this activity, not a single new, verifiable prediction has emerged.

Not a single theoretical problem was solved, and all sorts of signs and calculations were running wild.

Yet the physics community continues to push string theory with irrational enthusiasm.

By ruthlessly expelling opposing physicists from academia.

Meanwhile, physics was trapped in a paradigm doomed to be barren.

The author also suggests that the equation that beauty equals truth has captivated physicists for most of the past century, but that equation may have led them astray in recent years.

This book deals with ethical aspects and the way of life.

The eugenics programs of Europe and America, driven by the theoretical assumptions of Sir Francis Galton, brutally demonstrate how science can corrupt ethics.

The current reality of how computers are changing our lifestyles leads us to think deeply about the nature of happiness and creative fulfillment.

And the suffering that pervades the world makes us ask what limits there can be to the demands that morality imposes on us.

Beyond this, the author sharply and at times humorously tackles topics that have not only provided great insights but also become important points of contention in the history of modern intellectual thought, crossing the boundaries of various fields, such as the fierce debate over Saul Kripke's designation as the discoverer of a new theory, Richard Dawkins' hypothesis and core argument, and the four-color theorem.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 15, 2020

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 508 pages | 844g | 150*225*40mm

- ISBN13: 9791188941445

- ISBN10: 1188941445

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)