Earth Story

|

Description

Book Introduction

This book now tells the panorama of the Earth's 4.5 billion years and the future 5 billion years from today.

Hazen, a bestselling author and senior fellow at the Carnegie Institution of Institutions for Geophysics, brings an astrobiologist's imagination, a historian's perspective, and a naturalist's passion to vividly and meticulously depict the countless iterations of our planet, how changes at the atomic level translate into dramatic shifts in Earth's structure.

And we say that we are soon to be Earth.

To know the Earth is to know a part of ourselves, and moreover, the Earth is changing at a rate almost unprecedented in its long history.

In the rare instances of the past, life came at a tremendous cost.

The author says that in 5 billion years, the end of the Earth will come when the sun has burned all its hydrogen and is burning helium.

Of course, whether humanity goes extinct or not, the Earth will evolve.

The problem is simply our human choices.

The author says:

You would be a fool not to worry about the unstable changes on Earth today.

And we would be foolish to merely ponder the present state of the Earth and not fully utilize what it has to say about its remarkable and rich past, its unpredictable and dynamic present, and about ourselves and our place in the future.

Hazen, a bestselling author and senior fellow at the Carnegie Institution of Institutions for Geophysics, brings an astrobiologist's imagination, a historian's perspective, and a naturalist's passion to vividly and meticulously depict the countless iterations of our planet, how changes at the atomic level translate into dramatic shifts in Earth's structure.

And we say that we are soon to be Earth.

To know the Earth is to know a part of ourselves, and moreover, the Earth is changing at a rate almost unprecedented in its long history.

In the rare instances of the past, life came at a tremendous cost.

The author says that in 5 billion years, the end of the Earth will come when the sun has burned all its hydrogen and is burning helium.

Of course, whether humanity goes extinct or not, the Earth will evolve.

The problem is simply our human choices.

The author says:

You would be a fool not to worry about the unstable changes on Earth today.

And we would be foolish to merely ponder the present state of the Earth and not fully utilize what it has to say about its remarkable and rich past, its unpredictable and dynamic present, and about ourselves and our place in the future.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

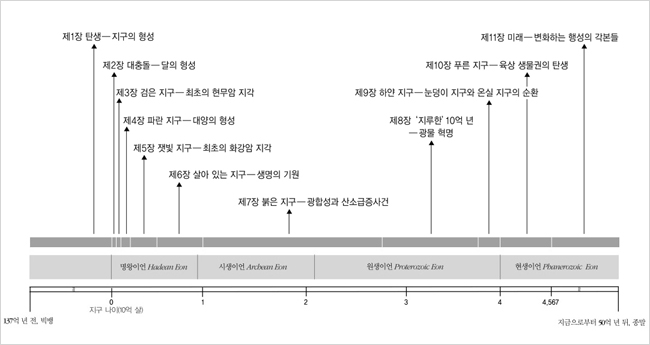

Entering

1.

Birth: The Formation of the Earth

2.

The Great Impact: The Formation of the Moon

3.

Black Earth: The First Basalt Crust

4.

Blue Earth: The Formation of the Oceans

5.

Gray Earth: The First Granite Crust

6.

Living Planet: The Origin of Life

7.

Red Earth: Photosynthesis and the Oxygenation Event

8.

A 'Boring' Billion Years: The Mineral Revolution

9.

White Earth: The Cycles of Snowball Earth and Greenhouse Earth

10.

Blue Earth: The Birth of the Terrestrial Biosphere

11.

The Future: Scripts for a Changing Planet

Epilogue/ Acknowledgments/ Translator's Note/ Index

1.

Birth: The Formation of the Earth

2.

The Great Impact: The Formation of the Moon

3.

Black Earth: The First Basalt Crust

4.

Blue Earth: The Formation of the Oceans

5.

Gray Earth: The First Granite Crust

6.

Living Planet: The Origin of Life

7.

Red Earth: Photosynthesis and the Oxygenation Event

8.

A 'Boring' Billion Years: The Mineral Revolution

9.

White Earth: The Cycles of Snowball Earth and Greenhouse Earth

10.

Blue Earth: The Birth of the Terrestrial Biosphere

11.

The Future: Scripts for a Changing Planet

Epilogue/ Acknowledgments/ Translator's Note/ Index

Detailed image

Into the book

Things were completely different 4.5 billion years ago.

The moon was only 24,000 kilometers away, so everything was spinning ridiculously fast, like a figure skater pulling in her arms to speed up her rotation.

First of all, the Earth rotates once every five hours.

It took the Earth a full year (about 8,766 hours) to orbit the Sun, and that time has not changed much over the history of the solar system.

But the short days lasted over 1,750 days a year, and the sun rose once every five hours(!).

(…) Not only did Earth have a five-hour day, but its neighboring moon also rotated much, much faster in its close orbit.

It took the moon only 84 hours—three and a half days in modern time—to orbit the Earth once. (pp. 62-63)

On the other hand, recent evidence suggests that the hot early ocean was briefly much saltier than it is today.

Sodium chloride, the salt commonly found on the table, dissolves immediately in hot water.

Today, about half of the Earth's salt is locked up in evaporite deposits associated with land-locked salt domes or dried-out salt lakes.

Most of this salt is isolated in thick layers deep within the Earth, but for the first 500 million years of Earth's existence, there were no continents for the salt to anchor.

Therefore, the salinity of the first oceans would have been twice that of the modern world.

In addition, other elements dissolved in the warm seawater (mainly iron, magnesium, and calcium, which are the main components of basalt) would have been present in higher concentrations. (p. 117)

The inner stony planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars) formed when the fiercely pulsating solar wind separated hydrogen and helium from the six heavier elements, sweeping away the lighter gaseous elements and sending them into the realm of the giant outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune).

On Earth, dense molten iron sank to the center, separating the metallic core from the peridotite-rich mantle.

Partial melting of the peridotite resulted in basalt, a rock rich in silicon, calcium, and aluminum that separated from the peridotite to form Earth's first thin, black crust.

As basalt erupted explosively and poured onto the surface, water and other volatiles separated from the basaltic magma, forming the first oceans and atmosphere.

Every step driven by heat separated or concentrated the elements, and every step resulted in the planet becoming more and more stratified and differentiated. (p. 123)

Plate tectonics not only produced island chains originating from granite, but also assembled them into continents.

The key lies in the simple fact that granite cannot be subducted.

Dense basalt easily sinks into the mantle, but granite floating on top of the basalt is like buoyant cork, and once formed, it remains on the surface.

As subduction produces more islands, the total area of granite increases irreversibly. (p. 146)

Imagine a subducting oceanic plate dotted with islands of granite that can't sink.

Basalt is subducted, but islands are not.

Since the islands must remain at the surface, they eventually form a strip of land just above the subduction zone.

Over tens of millions of years, more and more granite islands accumulate, forming an ever-widening belt, while at the same time, large amounts of freshly molten granite from the subducting slab rise up, increasing the thickness and width of the growing continent.

Islands join together to form protocontinents, and protocontinents join together to form continents.

It's similar to how chondrites in our solar system coalesce to form planetesimals, and then these planetesimals coalesce to form planets. (p. 146)

Before the emergence of life, redox reactions proceeded at a relatively leisurely pace.

But the first microbes learned to shuffle electrons at a faster rate, and in many places—primitive coastlines, near-surface waters, and ocean floor sediments—living cells became the mediators of these reactions.

Microbial communities made a living by speeding up the reactions of rocks. (…) In the process, life began to very slowly alter the Earth's surface environment.

Microorganisms exploited abundant energy, readily available in the form of reduced iron dissolved in the oceans of the Pleistocene and Archean periods.

Iron is oxidized to form red rust-colored hematite.

This chemical transformation can release enough energy to sustain an entire ecosystem.

Thus, the Archean banded iron formations found in Australia, South America, and other ancient regions may represent the remnants of a magnificent microbial buffet that lasted tens of millions of years.

And so began the remarkable coevolution of the geosphere and the biosphere. (p. 176)

The melting was only the most recognizable of many profound mineralogical changes.

Our recent chemical modeling work suggests that oxygenation events paved the way for as many as 3,000 minerals.

All of that paper was previously unknown minerals within our solar system.

Hundreds of new compounds of uranium, nickel, copper, manganese, and mercury arose only after life learned the trick of producing oxygen.

Many of the museum's most beautiful crystal specimens—blue-green copper minerals, purple cobalt crystals, yellow-orange uranium ores, and so on—bear powerful witness to a vibrant, living world.

Since it is unlikely that these hot minerals would have formed in an oxygen-free environment, it seems likely that life is directly or indirectly responsible for most of the Earth's 4,500 known minerals.

Remarkably, some of these new minerals provided evolving life with new ecological niches and new sources of chemical energy, allowing life to continue to coevolve with rocks and minerals. (p. 208)

In the adventure of Earth's evolution, dramatic change has been one constant, even after 200 million years since Earth celebrated its 2.5 billionth birthday.

The sun was formed by the coalescence of the solar nebula.

The dust surrounding the sun melted and became chondrules.

Chondrules clumped together to form planetesimals, which then became terrestrial planets with diameters of thousands of kilometers, including the proto-Earth.

Theia impact, the subsequent formation of the Moon, the solidification of an incandescent magma ocean into a black basalt crust pockmarked by thousands of erupting volcanoes, and soon a hot ocean that nearly covered the solid surface, leaving only the tops of the highest volcanic cones as dry land—all these dramatic events occurred within 500 million years.

Even during the less tumultuous two billion years since Earth's unique oceans gradually swelled, our planet's surface has been in constant flux, with granite emerging from molten basalt and protocontinents growing on the convection cells that drive plate tectonics.

It was on such a dynamic and variable world that life emerged, evolved, and eventually learned how to make oxygen.

Constant change was the Earth's hallmark. (Page 215)

There is perhaps no event in Earth's history that better illustrates a planet out of balance than this maddeningly aberrant snowball-greenhouse cycle.

The Neoproterozoic climate changed dramatically, leading to unprecedented increases in atmospheric oxygen, which paved the way for the first plants and animals and their migration across the continents.

Along with such biological innovations, the evolving Earth witnessed a multitude of animals swimming, burrowing, crawling, and flying, displaying increasingly extreme habitats and habits.

Moreover, with the advent of a hyper-oxygen atmosphere 650 million years ago, for the first time in Earth's long history, you, a time traveler, could breathe deeply into ancient, unfamiliar landscapes without suffering a painful death.

They may have collected green mucus as a meager meal while avoiding lethal doses of ultraviolet radiation. (p. 266)

Throughout Earth's history, the most dramatic transformations on Earth had to wait until the emergence of terrestrial plants.

The innovation is recorded in a unique, indomitable microfossil seed embedded in 475 million-year-old rocks.

Plant fossils are fragile and easily decayed, so no rocks from that period have been found, but the first true plants were probably not unlike modern liverworts.

The earth-hugging liverwort, which has no roots, is a descendant of green algae that could only survive in moist lowlands.

In 40 million-year-old sections of terrestrial rock around the world, only persistent seeds remain as the only physical evidence supporting the existence of terrestrial plants.

The evolution of these hardy, grass-green pioneers seems to have been steady but slow. (p. 281)

The increase in oxygen had beneficial effects on the animals.

More oxygen meant more energy, so the animals' metabolic rates increased.

Some animals grew larger and larger to exploit the extra energy.

The most dramatic results were giant insects, exemplified by a monstrous dragonfly with a wingspan of 60 centimeters.

The increased oxygen also made the atmosphere denser, making flight and gliding that much easier.

Other animals must have also migrated to higher altitudes where they could not previously survive.

Even at high altitudes, the air was thicker, so it would be possible to breathe now.

Life on the supercontinent Pangaea flourished for tens of millions of years.

Because the climate was mild and resources were abundant, life evolved freely.

But 250 million years ago, life collapsed in the most disastrous extinction event in Earth's history, abruptly and mysteriously. (p. 288)

The moon was only 24,000 kilometers away, so everything was spinning ridiculously fast, like a figure skater pulling in her arms to speed up her rotation.

First of all, the Earth rotates once every five hours.

It took the Earth a full year (about 8,766 hours) to orbit the Sun, and that time has not changed much over the history of the solar system.

But the short days lasted over 1,750 days a year, and the sun rose once every five hours(!).

(…) Not only did Earth have a five-hour day, but its neighboring moon also rotated much, much faster in its close orbit.

It took the moon only 84 hours—three and a half days in modern time—to orbit the Earth once. (pp. 62-63)

On the other hand, recent evidence suggests that the hot early ocean was briefly much saltier than it is today.

Sodium chloride, the salt commonly found on the table, dissolves immediately in hot water.

Today, about half of the Earth's salt is locked up in evaporite deposits associated with land-locked salt domes or dried-out salt lakes.

Most of this salt is isolated in thick layers deep within the Earth, but for the first 500 million years of Earth's existence, there were no continents for the salt to anchor.

Therefore, the salinity of the first oceans would have been twice that of the modern world.

In addition, other elements dissolved in the warm seawater (mainly iron, magnesium, and calcium, which are the main components of basalt) would have been present in higher concentrations. (p. 117)

The inner stony planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars) formed when the fiercely pulsating solar wind separated hydrogen and helium from the six heavier elements, sweeping away the lighter gaseous elements and sending them into the realm of the giant outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune).

On Earth, dense molten iron sank to the center, separating the metallic core from the peridotite-rich mantle.

Partial melting of the peridotite resulted in basalt, a rock rich in silicon, calcium, and aluminum that separated from the peridotite to form Earth's first thin, black crust.

As basalt erupted explosively and poured onto the surface, water and other volatiles separated from the basaltic magma, forming the first oceans and atmosphere.

Every step driven by heat separated or concentrated the elements, and every step resulted in the planet becoming more and more stratified and differentiated. (p. 123)

Plate tectonics not only produced island chains originating from granite, but also assembled them into continents.

The key lies in the simple fact that granite cannot be subducted.

Dense basalt easily sinks into the mantle, but granite floating on top of the basalt is like buoyant cork, and once formed, it remains on the surface.

As subduction produces more islands, the total area of granite increases irreversibly. (p. 146)

Imagine a subducting oceanic plate dotted with islands of granite that can't sink.

Basalt is subducted, but islands are not.

Since the islands must remain at the surface, they eventually form a strip of land just above the subduction zone.

Over tens of millions of years, more and more granite islands accumulate, forming an ever-widening belt, while at the same time, large amounts of freshly molten granite from the subducting slab rise up, increasing the thickness and width of the growing continent.

Islands join together to form protocontinents, and protocontinents join together to form continents.

It's similar to how chondrites in our solar system coalesce to form planetesimals, and then these planetesimals coalesce to form planets. (p. 146)

Before the emergence of life, redox reactions proceeded at a relatively leisurely pace.

But the first microbes learned to shuffle electrons at a faster rate, and in many places—primitive coastlines, near-surface waters, and ocean floor sediments—living cells became the mediators of these reactions.

Microbial communities made a living by speeding up the reactions of rocks. (…) In the process, life began to very slowly alter the Earth's surface environment.

Microorganisms exploited abundant energy, readily available in the form of reduced iron dissolved in the oceans of the Pleistocene and Archean periods.

Iron is oxidized to form red rust-colored hematite.

This chemical transformation can release enough energy to sustain an entire ecosystem.

Thus, the Archean banded iron formations found in Australia, South America, and other ancient regions may represent the remnants of a magnificent microbial buffet that lasted tens of millions of years.

And so began the remarkable coevolution of the geosphere and the biosphere. (p. 176)

The melting was only the most recognizable of many profound mineralogical changes.

Our recent chemical modeling work suggests that oxygenation events paved the way for as many as 3,000 minerals.

All of that paper was previously unknown minerals within our solar system.

Hundreds of new compounds of uranium, nickel, copper, manganese, and mercury arose only after life learned the trick of producing oxygen.

Many of the museum's most beautiful crystal specimens—blue-green copper minerals, purple cobalt crystals, yellow-orange uranium ores, and so on—bear powerful witness to a vibrant, living world.

Since it is unlikely that these hot minerals would have formed in an oxygen-free environment, it seems likely that life is directly or indirectly responsible for most of the Earth's 4,500 known minerals.

Remarkably, some of these new minerals provided evolving life with new ecological niches and new sources of chemical energy, allowing life to continue to coevolve with rocks and minerals. (p. 208)

In the adventure of Earth's evolution, dramatic change has been one constant, even after 200 million years since Earth celebrated its 2.5 billionth birthday.

The sun was formed by the coalescence of the solar nebula.

The dust surrounding the sun melted and became chondrules.

Chondrules clumped together to form planetesimals, which then became terrestrial planets with diameters of thousands of kilometers, including the proto-Earth.

Theia impact, the subsequent formation of the Moon, the solidification of an incandescent magma ocean into a black basalt crust pockmarked by thousands of erupting volcanoes, and soon a hot ocean that nearly covered the solid surface, leaving only the tops of the highest volcanic cones as dry land—all these dramatic events occurred within 500 million years.

Even during the less tumultuous two billion years since Earth's unique oceans gradually swelled, our planet's surface has been in constant flux, with granite emerging from molten basalt and protocontinents growing on the convection cells that drive plate tectonics.

It was on such a dynamic and variable world that life emerged, evolved, and eventually learned how to make oxygen.

Constant change was the Earth's hallmark. (Page 215)

There is perhaps no event in Earth's history that better illustrates a planet out of balance than this maddeningly aberrant snowball-greenhouse cycle.

The Neoproterozoic climate changed dramatically, leading to unprecedented increases in atmospheric oxygen, which paved the way for the first plants and animals and their migration across the continents.

Along with such biological innovations, the evolving Earth witnessed a multitude of animals swimming, burrowing, crawling, and flying, displaying increasingly extreme habitats and habits.

Moreover, with the advent of a hyper-oxygen atmosphere 650 million years ago, for the first time in Earth's long history, you, a time traveler, could breathe deeply into ancient, unfamiliar landscapes without suffering a painful death.

They may have collected green mucus as a meager meal while avoiding lethal doses of ultraviolet radiation. (p. 266)

Throughout Earth's history, the most dramatic transformations on Earth had to wait until the emergence of terrestrial plants.

The innovation is recorded in a unique, indomitable microfossil seed embedded in 475 million-year-old rocks.

Plant fossils are fragile and easily decayed, so no rocks from that period have been found, but the first true plants were probably not unlike modern liverworts.

The earth-hugging liverwort, which has no roots, is a descendant of green algae that could only survive in moist lowlands.

In 40 million-year-old sections of terrestrial rock around the world, only persistent seeds remain as the only physical evidence supporting the existence of terrestrial plants.

The evolution of these hardy, grass-green pioneers seems to have been steady but slow. (p. 281)

The increase in oxygen had beneficial effects on the animals.

More oxygen meant more energy, so the animals' metabolic rates increased.

Some animals grew larger and larger to exploit the extra energy.

The most dramatic results were giant insects, exemplified by a monstrous dragonfly with a wingspan of 60 centimeters.

The increased oxygen also made the atmosphere denser, making flight and gliding that much easier.

Other animals must have also migrated to higher altitudes where they could not previously survive.

Even at high altitudes, the air was thicker, so it would be possible to breathe now.

Life on the supercontinent Pangaea flourished for tens of millions of years.

Because the climate was mild and resources were abundant, life evolved freely.

But 250 million years ago, life collapsed in the most disastrous extinction event in Earth's history, abruptly and mysteriously. (p. 288)

---p.288

Publisher's Review

At some point 13.7 billion years ago, there was the Big Bang.

In the instant after the Big Bang, the first subatomic particles, electrons and quarks, transformed from pure energy into matter, and about 500,000 years later, the first atoms (hydrogen, which made up over 90 percent, with helium and trace amounts of lithium) inevitably formed the first stars.

After millions of years, most of the twenty-six elements at the top of the periodic table would have been created through nuclear fusion reactions in stars.

The first large stars exploded as supernovae, creating all the elements on the periodic table, including the "elements of life" such as carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur.

The first chemical reactions following the Big Bang combined hydrogen atoms to form hydrogen molecules, and after the first supernova, molecules of water, nitrogen, ammonia, methane, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide were formed.

About two or three hundred years after the Big Bang, the first mineral, a (pioneer) crystal of pure carbon, was formed, and about ten types of 'primitive minerals' were born using interplanetary dust as a matrix.

And about 4.5 billion years ago, the sun was formed and the planetesimals came together to form Earth (this is a brief summary of Chapter 1).

A paradigm of billions of years of co-evolution, woven together by elements, minerals, rocks, and organisms.

This book now covers the panorama of the Earth's 4.5 billion years and the future 5 billion years from now, but before that, it is necessary to examine the 'paradigm shift' level discussion centered on the paper "The Evolution of Minerals" published by the author and seven colleagues in 2008.

The key is the co-evolution of the geosphere (rocks and minerals) and the biosphere (living matter).

Billions of years ago, there were no minerals anywhere in the universe, and recent research suggests that not only do many rocks arise from life, but life itself may have arisen from rocks.

Of the roughly 4,500 minerals we know of, a full two-thirds could not have formed before the oxygenation event, and much of Earth's rich mineral diversity probably could not have arisen in the non-living world.

Therefore, the history of the Earth is a history of billions of years of co-evolution woven together by elements, minerals, rocks, and organisms.

Hazen, a bestselling author and senior fellow at the Carnegie Institution of Institutions for Geophysics, brings an astrobiologist's imagination, a historian's perspective, and a naturalist's passion to vividly and meticulously depict the countless iterations of our planet, how changes at the atomic level translate into dramatic shifts in Earth's structure.

The infancy of Earth when Theia collided with the first Earth and created the Moon; the childhood of Earth when the first crust was formed and the entire planet was dyed blue by oceans; the youth of Earth when continents rose and moved and collided with each other to create mountain ranges and open up oceans; the oxygenation event that dyed the land red as life arose and the pace of change rapidly accelerated; the Mesoproterozoic Era, a 'boring billion years' that seemed to maintain a dull 'stasis' and 'equilibrium' but prepared for a mineral revolution amid the pungent smell of sulfur compounds; the appearance of Earth going back and forth between a snowball and a greenhouse; and the last 500 million years when terrestrial life arose and Earth finally took on an appearance worthy of the name 'Blue Planet'.

Readers are drawn deeply into the magnificent drama of an ever-changing Earth, unfolded by a masterful storyteller.

We are the Earth!

And then you find out.

We are the Earth.

To know the Earth is to know a part of ourselves.

Moreover, the Earth is now changing at a rate almost unprecedented in its long history.

In the rare instances of the past, life came at a tremendous cost.

The author says that in 5 billion years, the end of the Earth will come when the sun has burned all its hydrogen and is burning helium.

Starting from that end and working backwards to the present day, it shows the axes of change: a desert world 2 billion years from now, the supercontinent Novopangaea (Amasya) 250 million years from now, an asteroid collision within 50 million years, a completely changed map 1 million years from now, a massive volcanic eruption 100,000 years from now, and an ice element 50,000 years from now.

So, in the next 100 years, global warming will be a problem.

Of course, whether humanity goes extinct or not, the Earth will evolve.

The problem is simply our human choice.

The author says:

You would be a fool not to worry about the unstable changes in the Earth today.

And we would be foolish to merely ponder the present state of the Earth and not fully utilize what it has to say about its remarkable and rich past, its unpredictable and dynamic present, and about ourselves and our place in the future.

In the instant after the Big Bang, the first subatomic particles, electrons and quarks, transformed from pure energy into matter, and about 500,000 years later, the first atoms (hydrogen, which made up over 90 percent, with helium and trace amounts of lithium) inevitably formed the first stars.

After millions of years, most of the twenty-six elements at the top of the periodic table would have been created through nuclear fusion reactions in stars.

The first large stars exploded as supernovae, creating all the elements on the periodic table, including the "elements of life" such as carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur.

The first chemical reactions following the Big Bang combined hydrogen atoms to form hydrogen molecules, and after the first supernova, molecules of water, nitrogen, ammonia, methane, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide were formed.

About two or three hundred years after the Big Bang, the first mineral, a (pioneer) crystal of pure carbon, was formed, and about ten types of 'primitive minerals' were born using interplanetary dust as a matrix.

And about 4.5 billion years ago, the sun was formed and the planetesimals came together to form Earth (this is a brief summary of Chapter 1).

A paradigm of billions of years of co-evolution, woven together by elements, minerals, rocks, and organisms.

This book now covers the panorama of the Earth's 4.5 billion years and the future 5 billion years from now, but before that, it is necessary to examine the 'paradigm shift' level discussion centered on the paper "The Evolution of Minerals" published by the author and seven colleagues in 2008.

The key is the co-evolution of the geosphere (rocks and minerals) and the biosphere (living matter).

Billions of years ago, there were no minerals anywhere in the universe, and recent research suggests that not only do many rocks arise from life, but life itself may have arisen from rocks.

Of the roughly 4,500 minerals we know of, a full two-thirds could not have formed before the oxygenation event, and much of Earth's rich mineral diversity probably could not have arisen in the non-living world.

Therefore, the history of the Earth is a history of billions of years of co-evolution woven together by elements, minerals, rocks, and organisms.

Hazen, a bestselling author and senior fellow at the Carnegie Institution of Institutions for Geophysics, brings an astrobiologist's imagination, a historian's perspective, and a naturalist's passion to vividly and meticulously depict the countless iterations of our planet, how changes at the atomic level translate into dramatic shifts in Earth's structure.

The infancy of Earth when Theia collided with the first Earth and created the Moon; the childhood of Earth when the first crust was formed and the entire planet was dyed blue by oceans; the youth of Earth when continents rose and moved and collided with each other to create mountain ranges and open up oceans; the oxygenation event that dyed the land red as life arose and the pace of change rapidly accelerated; the Mesoproterozoic Era, a 'boring billion years' that seemed to maintain a dull 'stasis' and 'equilibrium' but prepared for a mineral revolution amid the pungent smell of sulfur compounds; the appearance of Earth going back and forth between a snowball and a greenhouse; and the last 500 million years when terrestrial life arose and Earth finally took on an appearance worthy of the name 'Blue Planet'.

Readers are drawn deeply into the magnificent drama of an ever-changing Earth, unfolded by a masterful storyteller.

We are the Earth!

And then you find out.

We are the Earth.

To know the Earth is to know a part of ourselves.

Moreover, the Earth is now changing at a rate almost unprecedented in its long history.

In the rare instances of the past, life came at a tremendous cost.

The author says that in 5 billion years, the end of the Earth will come when the sun has burned all its hydrogen and is burning helium.

Starting from that end and working backwards to the present day, it shows the axes of change: a desert world 2 billion years from now, the supercontinent Novopangaea (Amasya) 250 million years from now, an asteroid collision within 50 million years, a completely changed map 1 million years from now, a massive volcanic eruption 100,000 years from now, and an ice element 50,000 years from now.

So, in the next 100 years, global warming will be a problem.

Of course, whether humanity goes extinct or not, the Earth will evolve.

The problem is simply our human choice.

The author says:

You would be a fool not to worry about the unstable changes in the Earth today.

And we would be foolish to merely ponder the present state of the Earth and not fully utilize what it has to say about its remarkable and rich past, its unpredictable and dynamic present, and about ourselves and our place in the future.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 10, 2014

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 357 pages | 654g | 152*225*26mm

- ISBN13: 9788964620410

- ISBN10: 8964620410

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)