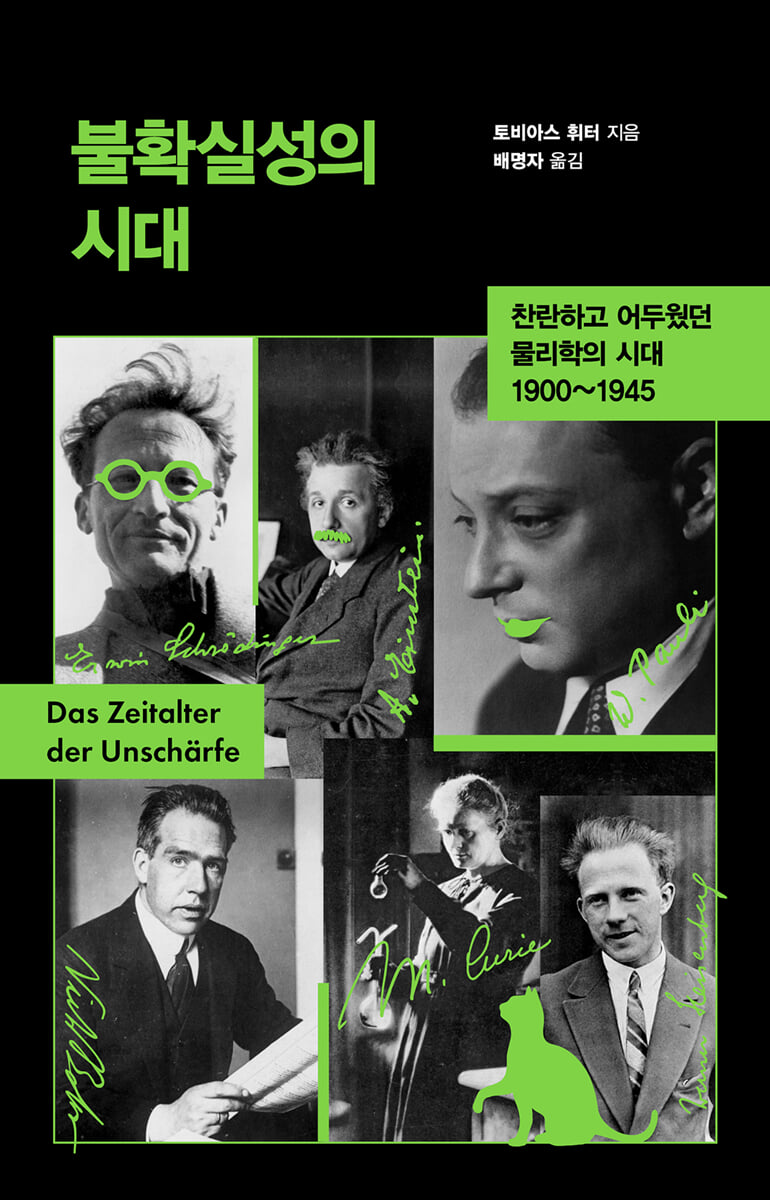

Age of Uncertainty

|

Description

Book Introduction

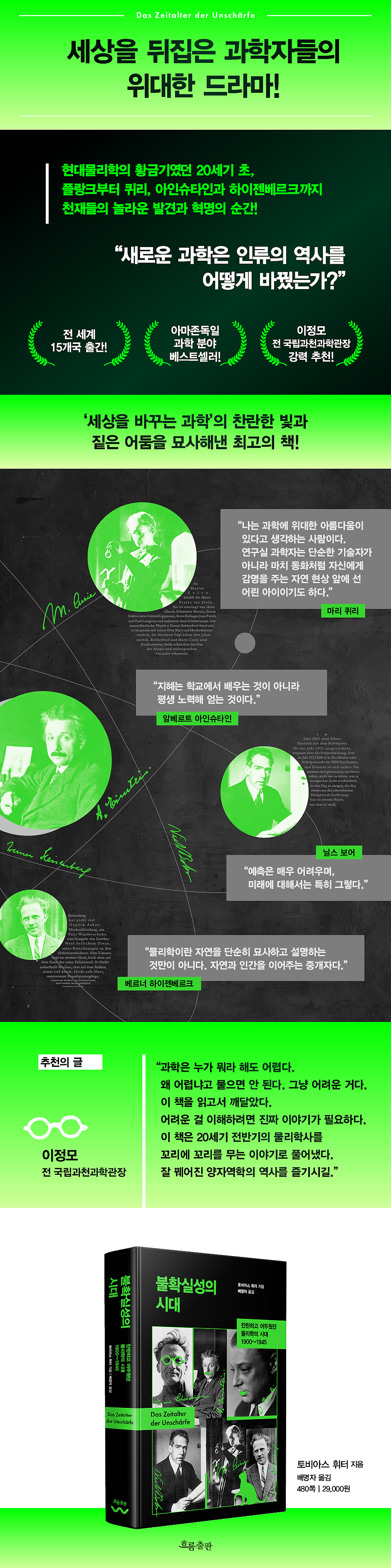

The great drama of scientists who turned the world upside down!

The early 20th century was the golden age of modern physics.

From Planck to Curie, Einstein and Bohr, and Heisenberg

Amazing discoveries and revolutionary moments from geniuses!

“How has new science changed the course of human history?”

Even those who don't know much about the history of science are likely to have heard of these terms at least once: 'Schrödinger's cat', 'Heisenberg's uncertainty principle', 'Bohr's complementarity principle', etc. These are words that inevitably appear when explaining the birth and development of quantum mechanics, the foundation of modern physics.

Quantum mechanics is the study of how particles and groups of particles in the microscopic world move under different forces. It is the science that underlies many new technologies that affect our daily lives today, including the operating principles of semiconductors, a key component of computers.

In the early 20th century, Einstein discovered the 'principle of relativity', which shook up the concepts of absolute time and space in classical physics and created a new time and space.

This book is a popular science nonfiction that captures the moments when the world's scientific minds, who decorated the history of 20th-century science, broke through the limitations of classical physics and created the brilliant achievements of modern physics, represented by the 'theory of relativity' and 'quantum mechanics.'

The author, a promising journalist, has drawn on letters, notes, research papers, and books left by contemporary scientists to create a compelling and dramatic account of the qualitative changes that took place in modern physics between 1900 and 1945.

But the brighter the light, the darker the shadow.

The era of relativity and quantum mechanics also overlaps with the era of the madness of war.

At a time when science not only changed history, but history also determined the uses of science, their amazing discoveries also led to the horrific disaster of the atomic bomb.

No one would want their academic passion and quest for truth to be used to manufacture weapons of mass destruction.

This is why the author calls this period, which was both brilliant and dark, and where motives and outcomes did not match, the “age of uncertainty.”

This is an excellent general science book that provides a glimpse into the historical flow of modern physics from its inception to its golden age.

The early 20th century was the golden age of modern physics.

From Planck to Curie, Einstein and Bohr, and Heisenberg

Amazing discoveries and revolutionary moments from geniuses!

“How has new science changed the course of human history?”

Even those who don't know much about the history of science are likely to have heard of these terms at least once: 'Schrödinger's cat', 'Heisenberg's uncertainty principle', 'Bohr's complementarity principle', etc. These are words that inevitably appear when explaining the birth and development of quantum mechanics, the foundation of modern physics.

Quantum mechanics is the study of how particles and groups of particles in the microscopic world move under different forces. It is the science that underlies many new technologies that affect our daily lives today, including the operating principles of semiconductors, a key component of computers.

In the early 20th century, Einstein discovered the 'principle of relativity', which shook up the concepts of absolute time and space in classical physics and created a new time and space.

This book is a popular science nonfiction that captures the moments when the world's scientific minds, who decorated the history of 20th-century science, broke through the limitations of classical physics and created the brilliant achievements of modern physics, represented by the 'theory of relativity' and 'quantum mechanics.'

The author, a promising journalist, has drawn on letters, notes, research papers, and books left by contemporary scientists to create a compelling and dramatic account of the qualitative changes that took place in modern physics between 1900 and 1945.

But the brighter the light, the darker the shadow.

The era of relativity and quantum mechanics also overlaps with the era of the madness of war.

At a time when science not only changed history, but history also determined the uses of science, their amazing discoveries also led to the horrific disaster of the atomic bomb.

No one would want their academic passion and quest for truth to be used to manufacture weapons of mass destruction.

This is why the author calls this period, which was both brilliant and dark, and where motives and outcomes did not match, the “age of uncertainty.”

This is an excellent general science book that provides a glimpse into the historical flow of modern physics from its inception to its golden age.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

prolog

Berlin, 1900 - A desperate desperate situation

Paris, 1903 - The Beginning of the Cracks

Bern, 1905 - Patent Office employee

Paris, 1906 - The tragic death of Pierre Curie

Berlin, 1909 - The End of the Airship

Prague, 1911 - Einstein speaks with flowers

Cambridge, 1911 - A young Danish man becomes an adult.

1912 North Atlantic - Sinking of the infallible Titanic

Munich, 1913 - Painters in Munich

Munich, 1914 - A Journey with the Atom

Berlin, 1915 - Perfect Theory, Immature Relationships

Germany 1916 - War and Peace

Berlin, 1917 - Einstein collapses

Berlin, 1918 - Plague

1919 Caribbean - Total Solar Eclipse

Munich, 1919 - A boy reading Plato

Berlin, 1920 - A Meeting of Masters

Göttingen, 1922 - The Son in Search of His Father

Munich, 1923 - Heisenberg soars through the trials.

Copenhagen, 1923 - Bohr and Einstein

Copenhagen, 1924 - The Last Attempt

Paris, 1924 - The Prince Who Saved the Atom

Heligoland, 1925 - The vast sea and the small atom

Cambridge, 1925 - The Quiet Genius

Leiden, 1925 - The Prophet and the Rotating Electron

1925 Arosa - Late Wind

Copenhagen, 1926 - Waves and Particles

Berlin, 1926 - Meeting the Gods of Physics

Berlin, 1926 - Planck's party

Göttingen, 1926 - The Disappearance of Reality

Munich, 1926 - turf wars

Copenhagen, 1926 - Art sculptures pouring down like rain

Copenhagen, 1926 - Dangerous Play

Copenhagen, 1927 - A World Becoming Uncertain

Como, 1927 - Rehearsal

Brussels, 1927 - The Great Debate

Berlin, 1930 - Germany is in bloom, Einstein is sick.

Brussels, 1930 - Round 2, complete defeat

Zurich, 1931 - Pauli's Dream

Copenhagen, 1932 - Faust in Copenhagen

Berlin, 1933 - Those who leave and those who stay

Leiden, 1933 - A sad ending

Oxford, 1935 - The Non-Existent Cat

Princeton, 1935 - Einstein's World Clarified Again

Garmisch, 1936 - Dirty Snow

Moscow, 1937 - On the other hand

Berlin, 1938 - The Dividing Nucleus

The Atlantic, 1939 - Shocking News

Copenhagen, 1941 - Awkward Relations

Berlin, 1942 - No Bomb for Hitler

Stockholm, 1943 - Escape

Princeton, 1943 - A Weakened Einstein

1945, England - The Power of Explosion

Epilogue

Berlin, 1900 - A desperate desperate situation

Paris, 1903 - The Beginning of the Cracks

Bern, 1905 - Patent Office employee

Paris, 1906 - The tragic death of Pierre Curie

Berlin, 1909 - The End of the Airship

Prague, 1911 - Einstein speaks with flowers

Cambridge, 1911 - A young Danish man becomes an adult.

1912 North Atlantic - Sinking of the infallible Titanic

Munich, 1913 - Painters in Munich

Munich, 1914 - A Journey with the Atom

Berlin, 1915 - Perfect Theory, Immature Relationships

Germany 1916 - War and Peace

Berlin, 1917 - Einstein collapses

Berlin, 1918 - Plague

1919 Caribbean - Total Solar Eclipse

Munich, 1919 - A boy reading Plato

Berlin, 1920 - A Meeting of Masters

Göttingen, 1922 - The Son in Search of His Father

Munich, 1923 - Heisenberg soars through the trials.

Copenhagen, 1923 - Bohr and Einstein

Copenhagen, 1924 - The Last Attempt

Paris, 1924 - The Prince Who Saved the Atom

Heligoland, 1925 - The vast sea and the small atom

Cambridge, 1925 - The Quiet Genius

Leiden, 1925 - The Prophet and the Rotating Electron

1925 Arosa - Late Wind

Copenhagen, 1926 - Waves and Particles

Berlin, 1926 - Meeting the Gods of Physics

Berlin, 1926 - Planck's party

Göttingen, 1926 - The Disappearance of Reality

Munich, 1926 - turf wars

Copenhagen, 1926 - Art sculptures pouring down like rain

Copenhagen, 1926 - Dangerous Play

Copenhagen, 1927 - A World Becoming Uncertain

Como, 1927 - Rehearsal

Brussels, 1927 - The Great Debate

Berlin, 1930 - Germany is in bloom, Einstein is sick.

Brussels, 1930 - Round 2, complete defeat

Zurich, 1931 - Pauli's Dream

Copenhagen, 1932 - Faust in Copenhagen

Berlin, 1933 - Those who leave and those who stay

Leiden, 1933 - A sad ending

Oxford, 1935 - The Non-Existent Cat

Princeton, 1935 - Einstein's World Clarified Again

Garmisch, 1936 - Dirty Snow

Moscow, 1937 - On the other hand

Berlin, 1938 - The Dividing Nucleus

The Atlantic, 1939 - Shocking News

Copenhagen, 1941 - Awkward Relations

Berlin, 1942 - No Bomb for Hitler

Stockholm, 1943 - Escape

Princeton, 1943 - A Weakened Einstein

1945, England - The Power of Explosion

Epilogue

Detailed image

Into the book

The Curies used a barn in the courtyard of the Institute of Physics and Chemistry, located in the Latin Quarter, the academic district of Paris, as their laboratory.

The wind coming through the gap in the tent blew a whistle.

The floor is always damp.

In the past, college students used to dissect corpses here until they were drunk.

Now, on the autopsy table are strange experimental tools such as glass bottles, wires, vacuum pumps, balance scales, prisms, batteries, gas burners, and furnaces.

German chemist Wilhelm Ostwald, who was granted an 'urgent request' to visit the Curies' laboratory, described the barracks laboratory as "a cross between a barn and a potato cellar."

“If I hadn’t seen the chemical experiments on the bench, I would have thought it was all a joke.” In this place reminiscent of an alchemist’s kitchen, the Curies would make some of the most important discoveries of the 20th century, which was just beginning.

They did not yet know that the cornerstone of a new worldview in physics was being laid here in the barn.

The Curies want to create a substance in this barn.

Pure radium, a substance that many colleagues had considered a "magic bullet" until only recently.

---From "Paris, 1903 - The Beginning of the Crack"

However, what Einstein called “very revolutionary” in his letter to Habicht was not the theory of relativity, but the theory of light quantum theory.

This is the only time he uses the word “revolutionary” in his paper.

Planck, who still regarded the quantum he had introduced into the world as a temporary means of calculation, did not agree with Einstein's light quantum theory.

However, they agreed to publish the paper.

Planck suddenly wondered who this amateur physicist from Bern was who had come up with all these wonderful and daring theories.

The papers Einstein listed in his letter to Habicht alone would seem to be enough to ensure his name was immortalized in the history of science.

Einstein wrote those papers in a matter of months, and in his spare time.

Never before has a scientist displayed such explosive creativity.

He then wrote a fifth paper, which he did not mention in his letter to Habicht.

The formula E=mc2 appears in this paper.

---From "Berne Patent Office Staff, 1905"

During the war, countless physicists wandered the world in search of safe and quiet places.

Bohr found such a place in his homeland.

He is now one of the few professors of theoretical physics in the world, and is already a celebrity in Denmark.

In the 1920s, more than 60 theoreticians visited the Bohr Institute and stayed for long periods.

Most of them stayed for several years.

They came from all over the world, including the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan.

Most of them were young.

Bohr personally covered the cost of their stay.

He created a new type of collaboration that went beyond physics.

Physicists worked together there, lived together, ate together, and played soccer together.

Bohr went skiing, hiking, and to the movies with them.

Bohr enjoyed watching western movies the most.

---From "Munich, 1914 - A Journey with the Atom"

This made Einstein a world star overnight.

Thomson, president of the Royal Society, said in a British newspaper that "the theory of relativity has opened up a whole new world of scientific ideas."

In post-war Germany, too, Einstein was celebrated, and articles about him and the theory of relativity poured in from all over.

The German weekly Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung introduced him as the successor to Copernicus, Kepler, and Newton.

The Times of London ran an article titled “A Revolution in Science / A New Theory of the Universe / Newton’s Ideas Overturned.”

(…) But kind criticism and malicious criticism permeated the cheers.

No one has ever explained Einstein's theories in understandable language, Thompson pointed out to a reporter.

The deep anxiety that spread across Europe during World War I, caused by mass deaths, false propaganda, social unhappiness, and the loss of traditional ways of life, was condensed into the theory of relativity.

Soon, an opposition movement sprouted.

The opposition movement championed Nazism and “German physics.”

---From "1919 Caribbean Total Solar Eclipse"

Since Maxwell, physicists have known it, and electrical engineers have used that knowledge to create radios and broadcasting equipment.

It should be a wave, but it's a particle? That's ridiculous! "So now there are two theories of light.

Both are essential, and despite the tremendous efforts of theoretical physicists over the past two decades, we must confess today that there is no logical connection between the two.” Both the wave theory and the particle theory of light make sense in some way.

Photons cannot explain wave phenomena of light, such as interference and refraction.

However, the Compton effect and the photoelectric effect cannot be explained without photons.

Light has two faces.

Waves and particles.

Physicists must learn to coexist with this.

---From "Munich 1923 - Heisenberg, Flying Through the Tests"

The pain that wave-particle duality brought to physicists was almost physical.

Einstein wrote this letter to Ehrenfest in August 1926:

“A wave here, a quantum there! Both realities are very solid.

But the devil made up a poem there (which really rhymed well).” In classical physics, the world was still in order.

There were waves and there were particles.

The two couldn't exist at the same time.

In quantum physics, particles sometimes behave like waves.

Or is it the other way around? Heisenberg was convinced of the existence of particles in his quantum mechanics.

Schrödinger thought of the world as a giant wave bundle.

However, it has been proven that the two approaches are mathematically equivalent.

How is this possible? From two completely different, seemingly incompatible starting points, the same result?

---From "Copenhagen 1926 - Waves and Particles"

With his paper, Heisenberg shook the very foundation of physics that Einstein and Schrödinger had considered causality.

“In the clear statement of the law of causality that ‘If you know the present accurately, you can calculate the future,’ what is wrong is not the conclusion but the premise.” We cannot know the present.

Since we cannot know both the position and velocity of an electron precisely at the same time, we can only calculate the probability of the electron's future position and velocity.

“Quantum mechanics clearly demonstrates the invalidity of the law of causality,” the paper’s final sentence states.

Einstein did not dare to go that far in revolutionizing space-time through the theory of relativity.

The clockwork universe once imagined by Newton no longer exists.

Even Immanuel Kant's statement that "all changes occur according to the law of cause and effect" no longer holds true.

---From "Copenhagen 1927 - A World Becoming Uncertain"

Meitner and Frisch took a winter walk and discussed the strange measurements from Berlin.

In the snow-covered Swedish forest, they sat on tree stumps and wrote down their thought processes on paper.

They designed a new model of the atomic nucleus.

Heavy nuclei can collide with neutrons and shatter like water droplets.

If the shape is sufficiently distorted at this point, the long-range electric repulsion becomes greater than the force holding the core together.

And then the nuke explodes.

Using Einstein's formula E=mc2, Meitner and Frisch estimated the energy of the explosion.

A staggering number was derived.

Frisch went to Copenhagen and explained the theory to Bohr.

Bore's hand touches his forehead.

“Oh, we were all so foolish! We could have predicted it first.” But Bohr now predicts something different.

What this energy from the nucleus can do is destruction.

And this destruction will happen faster than any physicist could have imagined.

That would darken the shining era of physics.

---From "Berlin, 1938 - The Dividing Nucleus"

Roosevelt had no time to read the atomic researchers' letters.

Because the war situation has gotten worse.

Hitler attacked Poland, and Britain and France declared war on Germany.

It was not until October 11, 1939, that the letter finally reached Roosevelt's desk.

“We must do something to prevent the Nazis from tearing us apart,” Roosevelt concluded.

That very day, he launched the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb.

At first, it progressed very slowly.

It was only after Einstein sent two successive letters to Roosevelt urging him to organize the project and reiterating his warning about Germany's bomb-making that momentum finally gained traction.

The Manhattan Project not only turned the United States into a uranium factory, but also required the cooperation of three countries: Britain, Canada, and the United States.

The wind coming through the gap in the tent blew a whistle.

The floor is always damp.

In the past, college students used to dissect corpses here until they were drunk.

Now, on the autopsy table are strange experimental tools such as glass bottles, wires, vacuum pumps, balance scales, prisms, batteries, gas burners, and furnaces.

German chemist Wilhelm Ostwald, who was granted an 'urgent request' to visit the Curies' laboratory, described the barracks laboratory as "a cross between a barn and a potato cellar."

“If I hadn’t seen the chemical experiments on the bench, I would have thought it was all a joke.” In this place reminiscent of an alchemist’s kitchen, the Curies would make some of the most important discoveries of the 20th century, which was just beginning.

They did not yet know that the cornerstone of a new worldview in physics was being laid here in the barn.

The Curies want to create a substance in this barn.

Pure radium, a substance that many colleagues had considered a "magic bullet" until only recently.

---From "Paris, 1903 - The Beginning of the Crack"

However, what Einstein called “very revolutionary” in his letter to Habicht was not the theory of relativity, but the theory of light quantum theory.

This is the only time he uses the word “revolutionary” in his paper.

Planck, who still regarded the quantum he had introduced into the world as a temporary means of calculation, did not agree with Einstein's light quantum theory.

However, they agreed to publish the paper.

Planck suddenly wondered who this amateur physicist from Bern was who had come up with all these wonderful and daring theories.

The papers Einstein listed in his letter to Habicht alone would seem to be enough to ensure his name was immortalized in the history of science.

Einstein wrote those papers in a matter of months, and in his spare time.

Never before has a scientist displayed such explosive creativity.

He then wrote a fifth paper, which he did not mention in his letter to Habicht.

The formula E=mc2 appears in this paper.

---From "Berne Patent Office Staff, 1905"

During the war, countless physicists wandered the world in search of safe and quiet places.

Bohr found such a place in his homeland.

He is now one of the few professors of theoretical physics in the world, and is already a celebrity in Denmark.

In the 1920s, more than 60 theoreticians visited the Bohr Institute and stayed for long periods.

Most of them stayed for several years.

They came from all over the world, including the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan.

Most of them were young.

Bohr personally covered the cost of their stay.

He created a new type of collaboration that went beyond physics.

Physicists worked together there, lived together, ate together, and played soccer together.

Bohr went skiing, hiking, and to the movies with them.

Bohr enjoyed watching western movies the most.

---From "Munich, 1914 - A Journey with the Atom"

This made Einstein a world star overnight.

Thomson, president of the Royal Society, said in a British newspaper that "the theory of relativity has opened up a whole new world of scientific ideas."

In post-war Germany, too, Einstein was celebrated, and articles about him and the theory of relativity poured in from all over.

The German weekly Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung introduced him as the successor to Copernicus, Kepler, and Newton.

The Times of London ran an article titled “A Revolution in Science / A New Theory of the Universe / Newton’s Ideas Overturned.”

(…) But kind criticism and malicious criticism permeated the cheers.

No one has ever explained Einstein's theories in understandable language, Thompson pointed out to a reporter.

The deep anxiety that spread across Europe during World War I, caused by mass deaths, false propaganda, social unhappiness, and the loss of traditional ways of life, was condensed into the theory of relativity.

Soon, an opposition movement sprouted.

The opposition movement championed Nazism and “German physics.”

---From "1919 Caribbean Total Solar Eclipse"

Since Maxwell, physicists have known it, and electrical engineers have used that knowledge to create radios and broadcasting equipment.

It should be a wave, but it's a particle? That's ridiculous! "So now there are two theories of light.

Both are essential, and despite the tremendous efforts of theoretical physicists over the past two decades, we must confess today that there is no logical connection between the two.” Both the wave theory and the particle theory of light make sense in some way.

Photons cannot explain wave phenomena of light, such as interference and refraction.

However, the Compton effect and the photoelectric effect cannot be explained without photons.

Light has two faces.

Waves and particles.

Physicists must learn to coexist with this.

---From "Munich 1923 - Heisenberg, Flying Through the Tests"

The pain that wave-particle duality brought to physicists was almost physical.

Einstein wrote this letter to Ehrenfest in August 1926:

“A wave here, a quantum there! Both realities are very solid.

But the devil made up a poem there (which really rhymed well).” In classical physics, the world was still in order.

There were waves and there were particles.

The two couldn't exist at the same time.

In quantum physics, particles sometimes behave like waves.

Or is it the other way around? Heisenberg was convinced of the existence of particles in his quantum mechanics.

Schrödinger thought of the world as a giant wave bundle.

However, it has been proven that the two approaches are mathematically equivalent.

How is this possible? From two completely different, seemingly incompatible starting points, the same result?

---From "Copenhagen 1926 - Waves and Particles"

With his paper, Heisenberg shook the very foundation of physics that Einstein and Schrödinger had considered causality.

“In the clear statement of the law of causality that ‘If you know the present accurately, you can calculate the future,’ what is wrong is not the conclusion but the premise.” We cannot know the present.

Since we cannot know both the position and velocity of an electron precisely at the same time, we can only calculate the probability of the electron's future position and velocity.

“Quantum mechanics clearly demonstrates the invalidity of the law of causality,” the paper’s final sentence states.

Einstein did not dare to go that far in revolutionizing space-time through the theory of relativity.

The clockwork universe once imagined by Newton no longer exists.

Even Immanuel Kant's statement that "all changes occur according to the law of cause and effect" no longer holds true.

---From "Copenhagen 1927 - A World Becoming Uncertain"

Meitner and Frisch took a winter walk and discussed the strange measurements from Berlin.

In the snow-covered Swedish forest, they sat on tree stumps and wrote down their thought processes on paper.

They designed a new model of the atomic nucleus.

Heavy nuclei can collide with neutrons and shatter like water droplets.

If the shape is sufficiently distorted at this point, the long-range electric repulsion becomes greater than the force holding the core together.

And then the nuke explodes.

Using Einstein's formula E=mc2, Meitner and Frisch estimated the energy of the explosion.

A staggering number was derived.

Frisch went to Copenhagen and explained the theory to Bohr.

Bore's hand touches his forehead.

“Oh, we were all so foolish! We could have predicted it first.” But Bohr now predicts something different.

What this energy from the nucleus can do is destruction.

And this destruction will happen faster than any physicist could have imagined.

That would darken the shining era of physics.

---From "Berlin, 1938 - The Dividing Nucleus"

Roosevelt had no time to read the atomic researchers' letters.

Because the war situation has gotten worse.

Hitler attacked Poland, and Britain and France declared war on Germany.

It was not until October 11, 1939, that the letter finally reached Roosevelt's desk.

“We must do something to prevent the Nazis from tearing us apart,” Roosevelt concluded.

That very day, he launched the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb.

At first, it progressed very slowly.

It was only after Einstein sent two successive letters to Roosevelt urging him to organize the project and reiterating his warning about Germany's bomb-making that momentum finally gained traction.

The Manhattan Project not only turned the United States into a uranium factory, but also required the cooperation of three countries: Britain, Canada, and the United States.

---From "Shocking News from the Atlantic, 1939"

Publisher's Review

The world view of classical physics has entered a place that cannot be explained.

How has the 'new science' changed human history?

'Science Discovering the World' and 'The World Changed by Science',

Capture the great physics scenes that occurred in the meantime!

Until the early 20th century, physicists believed that physics was nearing completion, just as geometry had been hundreds of years earlier.

In 1899, American physicist and Nobel laureate in physics Albert Michelson said, “All the important fundamental laws and facts of physics have been discovered.

It is so established that the possibility of new discoveries overtaking it is very low.

He also said, “What we will discover in the future is in the sixth place after the decimal point.”

On the other hand, James Maxwell, the founder of classical electrodynamics, told a slightly different story.

“The true reward for the effort of meticulous measurement is not greater accuracy, but the discovery of new fields of research and the development of new scientific ideas.”

Classical physics, symbolized by Newton's laws of motion in the 17th century and Maxwell's laws of electromagnetism in the 19th century, assumed time and space to be absolute entities that exist objectively, independent of the observer, and dealt with phenomena captured by the human eye or even larger macroscopic phenomena.

Classical physics, which interpreted natural phenomena from a causal and deterministic perspective with clear cause and effect, easily explained most of the phenomena experienced by humans until then.

However, in the 1890s, phenomena that were difficult to explain with existing classical physics theories began to appear.

Michelson was wrong, and Maxwell's prediction was correct.

Scientists are both 'discoverers' and 'interpreters'.

These are people who “want not only to know what is right, but also to understand why it is right.”

When science shines academically, it is the moment when it takes a step forward, discarding or revising existing theories to get closer to the truth.

At that moment, science changes from ‘science that discovers the world’ to ‘science that changes the world.’

"The Age of Uncertainty" is a popular science nonfiction that captures the moments when the outstanding scientific minds that adorned the history of 20th-century science broke through the limitations of classical physics and achieved the brilliant achievements of modern physics, represented by the two axes of "relativity theory" and "quantum mechanics."

Journalist Tobias Hütter vividly and three-dimensionally captures the 'great moments of 20th-century physics' that we must remember, using vivid sentences.

From the amazing discoveries of geniuses who laid the foundation for ‘new science’

A detailed account of the half-century since the end of two world wars.

A drama of cooperation and competition surrounding the birth and development of modern physics!

The 'new science' began with Max Planck in Berlin in 1900.

One of the challenges for 19th-century physicists was explaining the blackbody radiation curve using classical physics theory.

However, classical physics could not find a formula that correctly explained the relationship between temperature and color spectrum.

After studying blackbody radiation, even employing methods he had previously rejected, he announced that “energy is composed of a very specific number of finite, equivalent particles.”

The 'grains' he spoke of were soon to become quantum concepts, and Planck's quantum hypothesis later inspired Einstein's light quantum hypothesis.

The 'new science' was sprouting elsewhere too.

Marie Curie, the first female Nobel Prize winner and two-time Nobel Prize winner, was fascinated by the uranium rays discovered by Henri Becquerel in the early 20th century and continued her research on radiation. In the process, she succeeded in isolating radium, a substance with stronger radioactivity than uranium.

This opened up a new realm of science that would later develop into nuclear physics.

Meanwhile, unlike scientists who struggled in their laboratories and labs, there were also people who made discoveries that astonished the world in their daily lives, while dedicating themselves to the front lines of their profession.

The protagonist is Albert Einstein.

After reading Max Planck's presentation on the black body problem in 1900, he, then a third-grade examiner at the Swiss Patent Office, published a manuscript in 1905 ('On the Generation of Light from a Heuristic Point of View') arguing that light, or all electromagnetic radiation, is not a wave but is composed of quanta, a type of particle.

Until then, scientists thought that light was only a wave.

Planck introduced quantum concepts as a temporary means for calculation, but Einstein used his theory as a springboard to further revolutionary evolution of thinking.

Starting with these, 『The Age of Uncertainty』 names scientists who expanded new territories of science in the early to mid-20th century—Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, Louis de Broglie, Paul Dirac, Erwin Schrödinger, Lise Meitner, etc.—and dramatizes their acceptance, rebuttal, and supplementation of existing theories, rewriting the history of modern physics (especially quantum mechanics).

The 50 or so scenes selected by the author and included in the book are in themselves a genealogy of the history of modern physics.

In a drama spanning half a century, the scientists of the century become each other's teachers and students, sometimes empathizing with each other's academic struggles, and sometimes engaging in tense and fierce debates without giving an inch.

Even amidst the devastation of World War II, they read each other's papers and exchanged letters across borders, solidifying the foundation of a new science called quantum mechanics.

In particular, the parts that reconstruct the conversation between Heisenberg and Bohr regarding the atomic model and quantum theory ('Göttingen, 1922 - The Son Finds His Father'), the conversation between Einstein and Heisenberg regarding the theory of relativity and quantum theory (Berlin, 1926 - Meeting the Gods of Physics'), and the great debate between Bohr and Einstein at the 5th Solvay Conference on electrons and photons ('Brussels, 1927 - The Great Debate') are famous scenes in this book that vividly show their cooperation and conflict.

The great disaster known as the 'atomic bomb' looms behind the brilliant scientific revolution!

A masterpiece depicting the brilliant light and deep darkness of 'science that changes the world'!

Science changes history, but history also changes the uses of science.

"The Age of Uncertainty" doesn't just cover moments of wondrous scientific discovery.

In the early 20th century, two world wars that devastated Europe and the world at large forced scientists to contribute their knowledge to the war effort.

In particular, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in August 1945 were like a typhoon of catastrophic disaster brought about by the winds of a new scientific revolution.

At the height of Nazi tyranny, female scientist Lise Meitner escaped from Germany to Stockholm to escape Nazi oppression, but continued her research across borders through letters with her academic partner, Otto Hahn.

They wanted to create an element heavier than uranium, but in the process they bombarded uranium with neutrons and ended up with barium, which has a lighter atomic weight.

This not only revealed that atomic nuclei could be split and divided, but also that the energy produced was enormous.

This discovery is the basic principle that makes nuclear power possible today, but it was made during World War II, when the Allied Forces were fighting against militarism, including Nazism.

Scientists from the Allied camp, including Bohr and Einstein, were wary that the results of their nuclear fission research could be used dangerously by the Nazis, and informed U.S. President Roosevelt of this, and soon the Manhattan Project, the U.S. plan to develop an atomic bomb, began.

The project was a success, but in Hiroshima, where the bomb was dropped, 80,000 people died instantly.

It is said that Einstein later regretted his letter to Roosevelt so much that he called it “the biggest mistake of his life.”

The war had destroyed everything, and although the Allied victory was self-evident, the world was uncertain.

In 1927, Heisenberg announced the uncertainty principle, shaking the law of causality advocated by Einstein and Schrödinger.

“In the clear statement of the law of causality that ‘if you know the present accurately, you can calculate the future,’ what is wrong is not the conclusion but the premise.

(…) Quantum mechanics clearly demonstrates the invalidity of the law of causality.” The obsessive quest of scientists who “wanted not only to know what was right, but also to understand why it was right” mingled with the currents of history and led to ‘uncertain’ results that they had not anticipated.

This is why the author calls the period from 1900 to 1945, when the most dazzling achievements in modern physics were made, the 'Age of Uncertainty.'

"The Age of Uncertainty" is a non-fiction work that vividly examines the astonishing discoveries and revolutionary moments of contemporary scientists who laid the foundations of quantum mechanics, nuclear physics, and other fields during the first half of the 20th century, the golden age of modern physics, based on various historical materials.

By reading this vivid story reconstructed from scientists' letters, notes, research papers, diaries, and memoirs, you will be able to easily and clearly understand the divisions in the scientific camps of the time and the lineage and flow of modern physics even if you lack some background knowledge of the scientific theories mentioned in the book.

The moment you observe, the world changes.

You cannot observe the world without changing the world.

This insight led Heisenberg to quantum mechanics, and that was his dilemma.

He wanted to study the world.

Changing the world wasn't important to him.

And yet he changed the world, and he had no choice but to change the world with this tremendous theory in his hands.

Because he lived in a time when indifference did not exist in Nazi-controlled Germany.

Other physicists felt similarly.

Even Einstein, known as a pacifist, could not remain out of world history.

He also urged the creation of the atomic bomb.

He later regretted this.

This is the dark side of history, from the cracks in Marie Curie's fingertips to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

(…) Real history never ends.

The physicists in this book continued to work after 1945.

But none of them have made progress comparable to that of quantum mechanics or relativity.

Their theories, which they formulated a century ago, still stand strong today, embedded in our computer chips and medical equipment, and the debates they waged over the interpretation of these theories back then remain central to our day.

The objections Einstein raised to quantum mechanics are still raised by skeptical physicists today.

This history is not over yet.

(From the Epilogue)

How has the 'new science' changed human history?

'Science Discovering the World' and 'The World Changed by Science',

Capture the great physics scenes that occurred in the meantime!

Until the early 20th century, physicists believed that physics was nearing completion, just as geometry had been hundreds of years earlier.

In 1899, American physicist and Nobel laureate in physics Albert Michelson said, “All the important fundamental laws and facts of physics have been discovered.

It is so established that the possibility of new discoveries overtaking it is very low.

He also said, “What we will discover in the future is in the sixth place after the decimal point.”

On the other hand, James Maxwell, the founder of classical electrodynamics, told a slightly different story.

“The true reward for the effort of meticulous measurement is not greater accuracy, but the discovery of new fields of research and the development of new scientific ideas.”

Classical physics, symbolized by Newton's laws of motion in the 17th century and Maxwell's laws of electromagnetism in the 19th century, assumed time and space to be absolute entities that exist objectively, independent of the observer, and dealt with phenomena captured by the human eye or even larger macroscopic phenomena.

Classical physics, which interpreted natural phenomena from a causal and deterministic perspective with clear cause and effect, easily explained most of the phenomena experienced by humans until then.

However, in the 1890s, phenomena that were difficult to explain with existing classical physics theories began to appear.

Michelson was wrong, and Maxwell's prediction was correct.

Scientists are both 'discoverers' and 'interpreters'.

These are people who “want not only to know what is right, but also to understand why it is right.”

When science shines academically, it is the moment when it takes a step forward, discarding or revising existing theories to get closer to the truth.

At that moment, science changes from ‘science that discovers the world’ to ‘science that changes the world.’

"The Age of Uncertainty" is a popular science nonfiction that captures the moments when the outstanding scientific minds that adorned the history of 20th-century science broke through the limitations of classical physics and achieved the brilliant achievements of modern physics, represented by the two axes of "relativity theory" and "quantum mechanics."

Journalist Tobias Hütter vividly and three-dimensionally captures the 'great moments of 20th-century physics' that we must remember, using vivid sentences.

From the amazing discoveries of geniuses who laid the foundation for ‘new science’

A detailed account of the half-century since the end of two world wars.

A drama of cooperation and competition surrounding the birth and development of modern physics!

The 'new science' began with Max Planck in Berlin in 1900.

One of the challenges for 19th-century physicists was explaining the blackbody radiation curve using classical physics theory.

However, classical physics could not find a formula that correctly explained the relationship between temperature and color spectrum.

After studying blackbody radiation, even employing methods he had previously rejected, he announced that “energy is composed of a very specific number of finite, equivalent particles.”

The 'grains' he spoke of were soon to become quantum concepts, and Planck's quantum hypothesis later inspired Einstein's light quantum hypothesis.

The 'new science' was sprouting elsewhere too.

Marie Curie, the first female Nobel Prize winner and two-time Nobel Prize winner, was fascinated by the uranium rays discovered by Henri Becquerel in the early 20th century and continued her research on radiation. In the process, she succeeded in isolating radium, a substance with stronger radioactivity than uranium.

This opened up a new realm of science that would later develop into nuclear physics.

Meanwhile, unlike scientists who struggled in their laboratories and labs, there were also people who made discoveries that astonished the world in their daily lives, while dedicating themselves to the front lines of their profession.

The protagonist is Albert Einstein.

After reading Max Planck's presentation on the black body problem in 1900, he, then a third-grade examiner at the Swiss Patent Office, published a manuscript in 1905 ('On the Generation of Light from a Heuristic Point of View') arguing that light, or all electromagnetic radiation, is not a wave but is composed of quanta, a type of particle.

Until then, scientists thought that light was only a wave.

Planck introduced quantum concepts as a temporary means for calculation, but Einstein used his theory as a springboard to further revolutionary evolution of thinking.

Starting with these, 『The Age of Uncertainty』 names scientists who expanded new territories of science in the early to mid-20th century—Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, Louis de Broglie, Paul Dirac, Erwin Schrödinger, Lise Meitner, etc.—and dramatizes their acceptance, rebuttal, and supplementation of existing theories, rewriting the history of modern physics (especially quantum mechanics).

The 50 or so scenes selected by the author and included in the book are in themselves a genealogy of the history of modern physics.

In a drama spanning half a century, the scientists of the century become each other's teachers and students, sometimes empathizing with each other's academic struggles, and sometimes engaging in tense and fierce debates without giving an inch.

Even amidst the devastation of World War II, they read each other's papers and exchanged letters across borders, solidifying the foundation of a new science called quantum mechanics.

In particular, the parts that reconstruct the conversation between Heisenberg and Bohr regarding the atomic model and quantum theory ('Göttingen, 1922 - The Son Finds His Father'), the conversation between Einstein and Heisenberg regarding the theory of relativity and quantum theory (Berlin, 1926 - Meeting the Gods of Physics'), and the great debate between Bohr and Einstein at the 5th Solvay Conference on electrons and photons ('Brussels, 1927 - The Great Debate') are famous scenes in this book that vividly show their cooperation and conflict.

The great disaster known as the 'atomic bomb' looms behind the brilliant scientific revolution!

A masterpiece depicting the brilliant light and deep darkness of 'science that changes the world'!

Science changes history, but history also changes the uses of science.

"The Age of Uncertainty" doesn't just cover moments of wondrous scientific discovery.

In the early 20th century, two world wars that devastated Europe and the world at large forced scientists to contribute their knowledge to the war effort.

In particular, the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in August 1945 were like a typhoon of catastrophic disaster brought about by the winds of a new scientific revolution.

At the height of Nazi tyranny, female scientist Lise Meitner escaped from Germany to Stockholm to escape Nazi oppression, but continued her research across borders through letters with her academic partner, Otto Hahn.

They wanted to create an element heavier than uranium, but in the process they bombarded uranium with neutrons and ended up with barium, which has a lighter atomic weight.

This not only revealed that atomic nuclei could be split and divided, but also that the energy produced was enormous.

This discovery is the basic principle that makes nuclear power possible today, but it was made during World War II, when the Allied Forces were fighting against militarism, including Nazism.

Scientists from the Allied camp, including Bohr and Einstein, were wary that the results of their nuclear fission research could be used dangerously by the Nazis, and informed U.S. President Roosevelt of this, and soon the Manhattan Project, the U.S. plan to develop an atomic bomb, began.

The project was a success, but in Hiroshima, where the bomb was dropped, 80,000 people died instantly.

It is said that Einstein later regretted his letter to Roosevelt so much that he called it “the biggest mistake of his life.”

The war had destroyed everything, and although the Allied victory was self-evident, the world was uncertain.

In 1927, Heisenberg announced the uncertainty principle, shaking the law of causality advocated by Einstein and Schrödinger.

“In the clear statement of the law of causality that ‘if you know the present accurately, you can calculate the future,’ what is wrong is not the conclusion but the premise.

(…) Quantum mechanics clearly demonstrates the invalidity of the law of causality.” The obsessive quest of scientists who “wanted not only to know what was right, but also to understand why it was right” mingled with the currents of history and led to ‘uncertain’ results that they had not anticipated.

This is why the author calls the period from 1900 to 1945, when the most dazzling achievements in modern physics were made, the 'Age of Uncertainty.'

"The Age of Uncertainty" is a non-fiction work that vividly examines the astonishing discoveries and revolutionary moments of contemporary scientists who laid the foundations of quantum mechanics, nuclear physics, and other fields during the first half of the 20th century, the golden age of modern physics, based on various historical materials.

By reading this vivid story reconstructed from scientists' letters, notes, research papers, diaries, and memoirs, you will be able to easily and clearly understand the divisions in the scientific camps of the time and the lineage and flow of modern physics even if you lack some background knowledge of the scientific theories mentioned in the book.

The moment you observe, the world changes.

You cannot observe the world without changing the world.

This insight led Heisenberg to quantum mechanics, and that was his dilemma.

He wanted to study the world.

Changing the world wasn't important to him.

And yet he changed the world, and he had no choice but to change the world with this tremendous theory in his hands.

Because he lived in a time when indifference did not exist in Nazi-controlled Germany.

Other physicists felt similarly.

Even Einstein, known as a pacifist, could not remain out of world history.

He also urged the creation of the atomic bomb.

He later regretted this.

This is the dark side of history, from the cracks in Marie Curie's fingertips to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

(…) Real history never ends.

The physicists in this book continued to work after 1945.

But none of them have made progress comparable to that of quantum mechanics or relativity.

Their theories, which they formulated a century ago, still stand strong today, embedded in our computer chips and medical equipment, and the debates they waged over the interpretation of these theories back then remain central to our day.

The objections Einstein raised to quantum mechanics are still raised by skeptical physicists today.

This history is not over yet.

(From the Epilogue)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 1, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 480 pages | 750g | 140*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788965965695

- ISBN10: 8965965691

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)