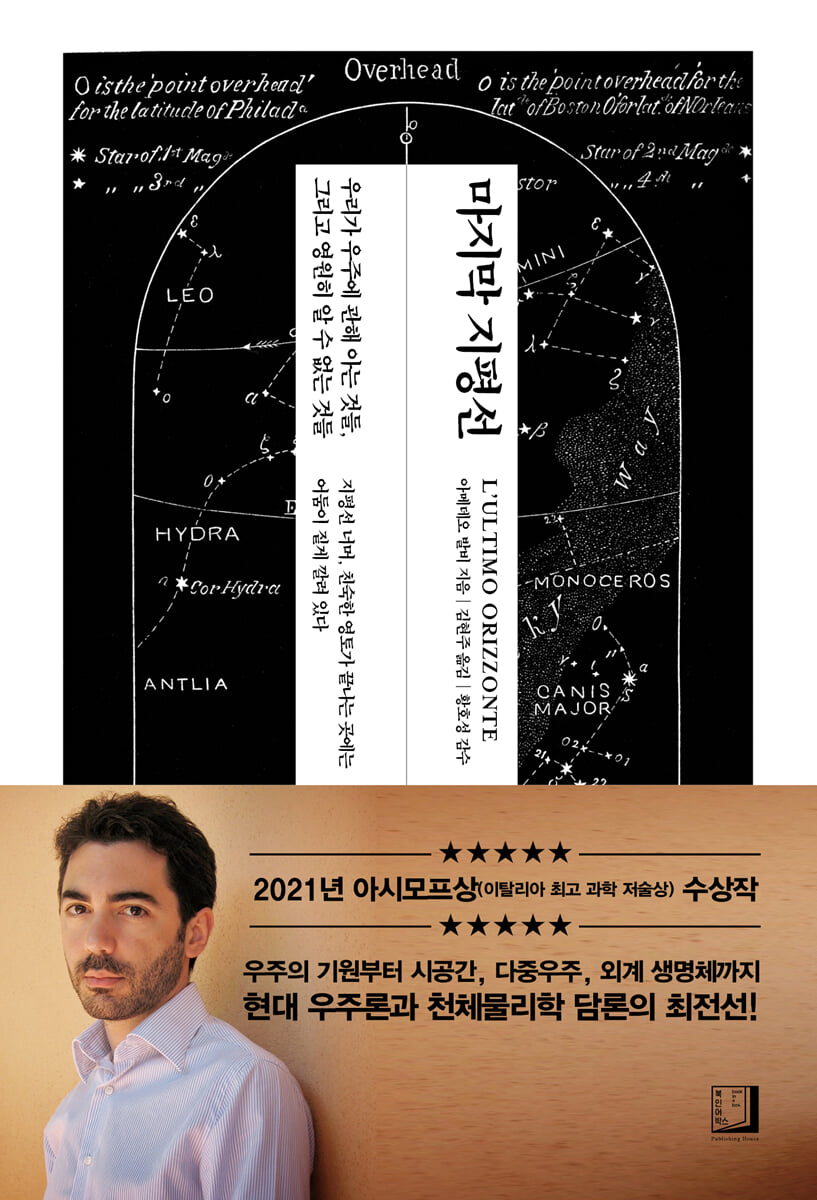

Last Horizon

|

Description

Book Introduction

“What can we know beyond the cosmic horizon?”

From the origin of the universe to its expansion and demise, the battle of physics surrounding the "existential universe"

10,000 students and teachers from 200 schools in 15 regions across Italy,

700 professors and local science committees award the best scientific popular work over a two-year period.

The final winners of the 6th Asimov Award (Premio Asimov 2021)!

“It provides valuable examples of scientific reality, and is an excellent guide to connecting the gap between theory and the reality described by strange mathematical formulas.” ─ The 6th Asimov Award Selection Committee

This book contains the fascinating debates at the forefront of modern physics surrounding the universe by Amede Balbi, a physicist who is recognized as a young talent in the Italian astronomy world.

In this book, the author interestingly unravels long-standing controversies about the universe that have long plagued cosmology and astrophysics researchers, from the moment humanity began to recognize the non-static but ever-changing history of the universe, which we call the Big Bang, to the matter and structure of the universe, the boundary of the observable universe, rapid inflation, the beginning and end of space-time, the existence of extraterrestrial life, and the problem of the multiverse, at a level that is accessible to the general public.

In particular, as one studies the universe, one naturally becomes interested in the origins of humans and the universe, and cannot help but raise fundamental questions about the existence of humans and God. This book unfolds like a well-organized humanities book, following the thought processes of physicists.

This book begins with what we already know, thanks to the remarkable advancements in physics over the past century, and gradually moves toward the "boundaries of the universe" that have yet to be explored, allowing us to fully experience the mysteries of the distant and distant universe.

Part I examines the established physics view of the universe and explains how we came to believe it exists the way it does. Part II ventures into new landscapes, where physics is less certain and more incomplete. Part III pauses to examine the challenges that confound us and the limited, or perhaps permanent, limits to our knowledge of the universe.

And in the final Part IV, we will answer questions that challenge the authority of science by pushing physics to its limits, such as the multiverse and life.

This book is a valuable guide and story of space exploration, using concepts gained during scientific research to explain the origin, evolution, and overall structure of the universe.

From the origin of the universe to its expansion and demise, the battle of physics surrounding the "existential universe"

10,000 students and teachers from 200 schools in 15 regions across Italy,

700 professors and local science committees award the best scientific popular work over a two-year period.

The final winners of the 6th Asimov Award (Premio Asimov 2021)!

“It provides valuable examples of scientific reality, and is an excellent guide to connecting the gap between theory and the reality described by strange mathematical formulas.” ─ The 6th Asimov Award Selection Committee

This book contains the fascinating debates at the forefront of modern physics surrounding the universe by Amede Balbi, a physicist who is recognized as a young talent in the Italian astronomy world.

In this book, the author interestingly unravels long-standing controversies about the universe that have long plagued cosmology and astrophysics researchers, from the moment humanity began to recognize the non-static but ever-changing history of the universe, which we call the Big Bang, to the matter and structure of the universe, the boundary of the observable universe, rapid inflation, the beginning and end of space-time, the existence of extraterrestrial life, and the problem of the multiverse, at a level that is accessible to the general public.

In particular, as one studies the universe, one naturally becomes interested in the origins of humans and the universe, and cannot help but raise fundamental questions about the existence of humans and God. This book unfolds like a well-organized humanities book, following the thought processes of physicists.

This book begins with what we already know, thanks to the remarkable advancements in physics over the past century, and gradually moves toward the "boundaries of the universe" that have yet to be explored, allowing us to fully experience the mysteries of the distant and distant universe.

Part I examines the established physics view of the universe and explains how we came to believe it exists the way it does. Part II ventures into new landscapes, where physics is less certain and more incomplete. Part III pauses to examine the challenges that confound us and the limited, or perhaps permanent, limits to our knowledge of the universe.

And in the final Part IV, we will answer questions that challenge the authority of science by pushing physics to its limits, such as the multiverse and life.

This book is a valuable guide and story of space exploration, using concepts gained during scientific research to explain the origin, evolution, and overall structure of the universe.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

introduction

Part I | The Known World

1.

question

2.

Exploration

3.

space-time

4.

expansion

5.

element

6.

heat

7.

cornerstone

Part II | Shadow Line

8.

model

9.

rapid expansion

10.

substance

11.

vacuum

12.

geometry

13.

unknown

Part III | The Pillars of Hercules

14.

margin

15.

horizon

16.

Finiteness

17.

Originality

18.

hour

19.

energy

20.

principle

Part IV | Towards Further Distance

21.

genesis

22.

contingency

23.

rule

24.

multiverse

25.

living things

26.

plan

Reviews

Americas

introduction

Part I | The Known World

1.

question

2.

Exploration

3.

space-time

4.

expansion

5.

element

6.

heat

7.

cornerstone

Part II | Shadow Line

8.

model

9.

rapid expansion

10.

substance

11.

vacuum

12.

geometry

13.

unknown

Part III | The Pillars of Hercules

14.

margin

15.

horizon

16.

Finiteness

17.

Originality

18.

hour

19.

energy

20.

principle

Part IV | Towards Further Distance

21.

genesis

22.

contingency

23.

rule

24.

multiverse

25.

living things

26.

plan

Reviews

Americas

Detailed image

Into the book

In all history without a beginning, the existence of reality is accepted as an incomprehensible fact.

It only explains the form reality takes in the world, the origins of the structures we observe.

But in this case, you can't help but fall into a dizzying cycle of endless regression.

There is no first cause, but there are endless causes preceding any event.

Regardless of logical or conceptual difficulties, only one of the two possibilities accurately describes the universe we live in: a universe that originally existed or a universe that began to exist at some point in the past.

Which side is right?

---From "Questions"

Science is a process of exploring reality, and scientific knowledge can be seen as similar to a world map.

Maps do not simply encompass the expanding territory we gradually explore as we explore reality, nor do they become increasingly accurate and detailed.

The important thing to remember here is that maps are not reality.

No matter how sophisticated our theories are, they are still idealized simplifications, conceptual tools we use to navigate the complex real world.

---From "Exploration"

The classical Big Bang model, the Friedmann-Lemaître model, is very simple.

When explaining the evolution of the universe, we only need to know how much matter it contains (the average density of the universe) and the rate at which it is expanding (the constant named after Hubble).

These two physical quantities are measurable, and in fact, for decades, creating concepts about their values has been a major goal of cosmology.

Unfortunately, however, the simplicity of this model cannot be overcome.

Because the universe is much more complex than this model.

---From "Rapid Expansion"

In the late 1960s, the discovery of the cosmic microwave background not only provided crucial evidence supporting the Big Bang model, but also opened the door to exploring what was happening in the primordial universe.

Not metaphorically, but by scanning the sky in all directions with a very sensitive antenna and collecting the primordial photon rain that falls, we can image the distribution of matter in the universe at the time protons and electrons recombinated, just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Of course, the expression 'just passed' is a relative term, but compared to the 13.8 billion year history of the universe, isn't 380,000 years nothing?

---From "Geometry"

The reality we access can be perceived through our everyday senses or through the advancements made possible by technology.

So the elements of the world change in each era according to the changes in the possibilities we obtain.

The vision of 18th-century scientists did not include atoms, viruses, galaxies, electric fields, or dark matter.

We must leave open the possibility that we may be placing in the vaults of our descendants the true nature of 'substantial objects' that are still unknown to us.

On the other hand, we must recognize the ultimate limits of our vision.

---From "Limits"

This means that there is a 'horizon' in space.

We are trapped in a circular bubble of information and cannot see beyond the horizon.

It is believed that there may be another universe outside the bubble, but it cannot be observed.

Of course, this horizon is not the edge of the universe, and the universe is not spherical.

Just as with the Earth's horizon, if we could change our position in space, the circumference of the horizon would also change, and we would see different areas of space.

But the conclusion remains the same: there are inevitable limits to the scale of the universe we can directly explore.

---From "Horizon"

Not only can we not create universes in the laboratory, we can't observe many examples of the universe.

The universe is as it is and we must accept it.

All we can do is use the known laws of physics, assume that these laws apply to the entire universe—that is, to every point in space and at every epoch—and arrive at a satisfactory explanation of the evolution of the universe.

However, this evolution, while not impossible, has many aspects that are difficult to explain.

In particular, we find no way to determine whether a particular aspect of cosmic evolution is accidental, related to a particular combination of initial conditions, or absolutely necessary.

---From "Originality"

It can be said that the universe is in a state of rapid population decline.

And ahead of them lies an increasingly dark future.

While the brightest stars will fade away one by one first, the smallest, less luminous stars can continue to shine for billions of years, illuminating the universe with their reddish light until the last light goes out.

Compared to the timescale of the universe, which is made up of brightly shining skies, we have lived for a relatively short period of time.

This also adds to the value of our enjoyment of the space show.

---From "Time"

Ultimately, the primordial universe is the only laboratory in which we can test our theories about the nature of reality.

So we end up in a vicious cycle of applying known physics to impractical energy levels, making predictions about how the universe will behave under those conditions, and then either confirming or rejecting our hypotheses through cosmological observations.

But if a prediction is based on an idea that has no possibility of being verified in the first place, any conclusion is bound to be problematic.

This is a fundamental weakness that is not easy to overcome.

---From "Energy"

The attraction to the Absolute is not for the finite, dependent, and limited scientist, and it can be said that it is not a subject that science should deal with.

Science discovers things through relationships.

But science leads us towards understanding the universe as everything that exists in the world.

So I believe it's important for scientists to remember the limits of what we can know.

Because it shows that there are questions that lie entirely outside the realm of empirical evaluability, and that addressing these questions requires relying on assumptions or choices that are, in the ultimate analysis, philosophical rather than scientific.

---From "Principles"

The biggest obstacle is that the two great theories of modern physics, general relativity and quantum physics, are incompatible.

Both theories have demonstrated unprecedented validity and efficiency in their respective fields.

General relativity has very accurately described the properties of large-scale spacetime where gravity is crucial, and quantum mechanics has had great success in dealing with microscopic phenomena where gravity can be ignored.

But if you try to put these two theories together, both will end up in a state of madness.

---From "Origin"

Regardless of whether the universe had an origin in the flow of time, there is a problem in explaining why the universe is formed in the way we observe it.

Here again we are faced with several possibilities.

The first possibility is that the universe is 'accidental'.

What does this mean? It means that the universe could have been different from what it currently is.

In this case, we need an explanation of the chosen system, that is, an explanation of why it exists in this way rather than in other possible ways.

---From "'Contingency'"

The overall effect of increasing entropy is to upset the balance between past and future, and to dictate the direction of time in the direction of increasing entropy, that is, in the direction in which the arrow of time flies.

But there is something to be careful about.

The entropy of the past universe must have been very low.

This means that the primordial universe must have been like a whole cup, not a broken cup.

Here's where the problem arises: as we've seen, the universe is much more likely to be disordered than ordered.

It's incredibly likely.

Therefore, we must explain why the universe was so far from its maximum possible entropy state in the past.

---From "'Contingency'"

From living organisms and organisms to intelligent observers trying to understand the workings of the universe, is it right to treat other entities in the universe as trivial and irrelevant to us? And what is the connection between the unique properties of the universe and its ability to generate the complex physical structures necessary for biological activity? In fact, our long-standing approach to this question has generally been to ignore it.

In other words, the universe was viewed solely as a physical system that had to be understood independently of the presence of observers within it.

---From "'Lifeform'"

We need to think about who can explain what science cannot explain and how.

Science is the best way we have found to reach conclusions that should be shared globally, transcending barriers of culture and social class.

And it is also a great vehicle for representing knowledge, progress, and democracy.

We should be suspicious of those who think they have the truth in their pockets, who convey certainty when it isn't, and who use authority, power, or violence to impose their views, even if they try to satisfy our yearning for meaning and certainty.

---From "The Plan"

There is nothing that amazes me more than the fact that there is a universe out there.

The fact is that there exists an awareness that can experience all of this.

Awareness is something truly unique, a subjective experience, a constantly changing mass of perception, accompanied by a temporary aggregation of atoms that I call 'me' at the precise juncture of space and time.

But just as we cannot have a comprehensive view of the whole of reality from the outside, when we base our focus on a center, everything seems to converge toward that center.

Then neither the universe nor consciousness can be objects of observation.

It only explains the form reality takes in the world, the origins of the structures we observe.

But in this case, you can't help but fall into a dizzying cycle of endless regression.

There is no first cause, but there are endless causes preceding any event.

Regardless of logical or conceptual difficulties, only one of the two possibilities accurately describes the universe we live in: a universe that originally existed or a universe that began to exist at some point in the past.

Which side is right?

---From "Questions"

Science is a process of exploring reality, and scientific knowledge can be seen as similar to a world map.

Maps do not simply encompass the expanding territory we gradually explore as we explore reality, nor do they become increasingly accurate and detailed.

The important thing to remember here is that maps are not reality.

No matter how sophisticated our theories are, they are still idealized simplifications, conceptual tools we use to navigate the complex real world.

---From "Exploration"

The classical Big Bang model, the Friedmann-Lemaître model, is very simple.

When explaining the evolution of the universe, we only need to know how much matter it contains (the average density of the universe) and the rate at which it is expanding (the constant named after Hubble).

These two physical quantities are measurable, and in fact, for decades, creating concepts about their values has been a major goal of cosmology.

Unfortunately, however, the simplicity of this model cannot be overcome.

Because the universe is much more complex than this model.

---From "Rapid Expansion"

In the late 1960s, the discovery of the cosmic microwave background not only provided crucial evidence supporting the Big Bang model, but also opened the door to exploring what was happening in the primordial universe.

Not metaphorically, but by scanning the sky in all directions with a very sensitive antenna and collecting the primordial photon rain that falls, we can image the distribution of matter in the universe at the time protons and electrons recombinated, just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Of course, the expression 'just passed' is a relative term, but compared to the 13.8 billion year history of the universe, isn't 380,000 years nothing?

---From "Geometry"

The reality we access can be perceived through our everyday senses or through the advancements made possible by technology.

So the elements of the world change in each era according to the changes in the possibilities we obtain.

The vision of 18th-century scientists did not include atoms, viruses, galaxies, electric fields, or dark matter.

We must leave open the possibility that we may be placing in the vaults of our descendants the true nature of 'substantial objects' that are still unknown to us.

On the other hand, we must recognize the ultimate limits of our vision.

---From "Limits"

This means that there is a 'horizon' in space.

We are trapped in a circular bubble of information and cannot see beyond the horizon.

It is believed that there may be another universe outside the bubble, but it cannot be observed.

Of course, this horizon is not the edge of the universe, and the universe is not spherical.

Just as with the Earth's horizon, if we could change our position in space, the circumference of the horizon would also change, and we would see different areas of space.

But the conclusion remains the same: there are inevitable limits to the scale of the universe we can directly explore.

---From "Horizon"

Not only can we not create universes in the laboratory, we can't observe many examples of the universe.

The universe is as it is and we must accept it.

All we can do is use the known laws of physics, assume that these laws apply to the entire universe—that is, to every point in space and at every epoch—and arrive at a satisfactory explanation of the evolution of the universe.

However, this evolution, while not impossible, has many aspects that are difficult to explain.

In particular, we find no way to determine whether a particular aspect of cosmic evolution is accidental, related to a particular combination of initial conditions, or absolutely necessary.

---From "Originality"

It can be said that the universe is in a state of rapid population decline.

And ahead of them lies an increasingly dark future.

While the brightest stars will fade away one by one first, the smallest, less luminous stars can continue to shine for billions of years, illuminating the universe with their reddish light until the last light goes out.

Compared to the timescale of the universe, which is made up of brightly shining skies, we have lived for a relatively short period of time.

This also adds to the value of our enjoyment of the space show.

---From "Time"

Ultimately, the primordial universe is the only laboratory in which we can test our theories about the nature of reality.

So we end up in a vicious cycle of applying known physics to impractical energy levels, making predictions about how the universe will behave under those conditions, and then either confirming or rejecting our hypotheses through cosmological observations.

But if a prediction is based on an idea that has no possibility of being verified in the first place, any conclusion is bound to be problematic.

This is a fundamental weakness that is not easy to overcome.

---From "Energy"

The attraction to the Absolute is not for the finite, dependent, and limited scientist, and it can be said that it is not a subject that science should deal with.

Science discovers things through relationships.

But science leads us towards understanding the universe as everything that exists in the world.

So I believe it's important for scientists to remember the limits of what we can know.

Because it shows that there are questions that lie entirely outside the realm of empirical evaluability, and that addressing these questions requires relying on assumptions or choices that are, in the ultimate analysis, philosophical rather than scientific.

---From "Principles"

The biggest obstacle is that the two great theories of modern physics, general relativity and quantum physics, are incompatible.

Both theories have demonstrated unprecedented validity and efficiency in their respective fields.

General relativity has very accurately described the properties of large-scale spacetime where gravity is crucial, and quantum mechanics has had great success in dealing with microscopic phenomena where gravity can be ignored.

But if you try to put these two theories together, both will end up in a state of madness.

---From "Origin"

Regardless of whether the universe had an origin in the flow of time, there is a problem in explaining why the universe is formed in the way we observe it.

Here again we are faced with several possibilities.

The first possibility is that the universe is 'accidental'.

What does this mean? It means that the universe could have been different from what it currently is.

In this case, we need an explanation of the chosen system, that is, an explanation of why it exists in this way rather than in other possible ways.

---From "'Contingency'"

The overall effect of increasing entropy is to upset the balance between past and future, and to dictate the direction of time in the direction of increasing entropy, that is, in the direction in which the arrow of time flies.

But there is something to be careful about.

The entropy of the past universe must have been very low.

This means that the primordial universe must have been like a whole cup, not a broken cup.

Here's where the problem arises: as we've seen, the universe is much more likely to be disordered than ordered.

It's incredibly likely.

Therefore, we must explain why the universe was so far from its maximum possible entropy state in the past.

---From "'Contingency'"

From living organisms and organisms to intelligent observers trying to understand the workings of the universe, is it right to treat other entities in the universe as trivial and irrelevant to us? And what is the connection between the unique properties of the universe and its ability to generate the complex physical structures necessary for biological activity? In fact, our long-standing approach to this question has generally been to ignore it.

In other words, the universe was viewed solely as a physical system that had to be understood independently of the presence of observers within it.

---From "'Lifeform'"

We need to think about who can explain what science cannot explain and how.

Science is the best way we have found to reach conclusions that should be shared globally, transcending barriers of culture and social class.

And it is also a great vehicle for representing knowledge, progress, and democracy.

We should be suspicious of those who think they have the truth in their pockets, who convey certainty when it isn't, and who use authority, power, or violence to impose their views, even if they try to satisfy our yearning for meaning and certainty.

---From "The Plan"

There is nothing that amazes me more than the fact that there is a universe out there.

The fact is that there exists an awareness that can experience all of this.

Awareness is something truly unique, a subjective experience, a constantly changing mass of perception, accompanied by a temporary aggregation of atoms that I call 'me' at the precise juncture of space and time.

But just as we cannot have a comprehensive view of the whole of reality from the outside, when we base our focus on a center, everything seems to converge toward that center.

Then neither the universe nor consciousness can be objects of observation.

---From "Review"

Publisher's Review

Are there limits to what we can know about the universe?

If so, has that limit already been reached?

We know the age of the universe very precisely, and we also know the matter and energy that make up the universe and its large-scale structure.

The physical systems that allowed the universe to evolve from an initially uncomplicated and simple state to the rich and complex state we inhabit today have also been identified.

But as we move toward the boundaries of space and time, we encounter problems that seriously challenge our tools and concepts.

Is the universe finite or infinite? Since space and time had a beginning, will they also have an end? Could the laws of nature have been different in the past? Are there other universes besides ours? Why is there something rather than nothing? _Main text p.

17

The James Webb Space Telescope, jointly developed and launched by the United States, the European Union, and others, is widely considered to have opened a new era in space observation by sending back better-than-expected results about stars and galaxies outside the solar system.

In fact, the incredibly realistic images that are being released one after another allow us to enjoy the wonders of the universe in a much more vivid way than the results sent back by Hubble, the best telescope ever.

Moreover, it is true that expectations are growing higher than ever that hints of extraterrestrial life, a long-held dream in astrophysics, may be discovered.

This is clearly a remarkable result of the scientific advancements that humanity has accumulated since the last century, and it deserves to be evaluated as another step forward for humanity in narrowing the boundaries of ignorance beyond the distant cosmic horizon and in understanding the universe shrouded in darkness.

However, if we consider whether modern astrophysics, which is developing so rapidly, is providing satisfactory answers to the questions we want to know about the universe, it becomes a slightly different question.

Strange as it may sound, although we are now inundated with a significant amount of high-quality new data, and very fine details of our existing picture of the universe have been reconstructed to a significant degree, the achievements of the last dozen years or so have not dramatically changed this overall picture of the universe since the turn of the century, when Einstein's general theory of relativity ushered in the 20th century and the Big Bang model was established to paint the overall picture of the universe.

What happened after the new millennium?

“It was disappointingly, surprisingly, nothing special,” says the book’s author, Italian astrophysicist Amedeo Balbi.

We still haven't figured out the beginning of the universe (inflation), just before it began expanding, and while we suspect there's dark matter that makes up most of the universe, we have no idea what it is.

The cosmological constant (dark energy) is the best option to explain the acceleration of the universe, but there are still doubts about its theoretical nature.

Beyond the cosmic horizon, we cannot know whether our universe is the only one or one of many, and we cannot be certain whether it is the only universe in this vast universe.

The worse news is that there's no guarantee that there will be light to illuminate the shadowy parts of that distant landscape.

Every time something seemingly small would come up, I held out hope that I would discover a new path, but when I dug deeper, nothing seemed meaningful.

Beyond the horizon where familiar territory ends,

What do we know and what do we not know?

Are there limits to what we can know about the universe? If so, have we already reached them? These questions are especially worth pondering when we feel we're drifting further and further from our destination, or when we encounter obstacles that seem insurmountable.

However, it should be borne in mind that the history of science has often fallen into two extreme situations.

The two are 'We will never know about the universe' and 'We already know everything there is to know.'

_From the introduction

So should we underestimate the immense effort we're making today to learn about the universe? Of course not.

The author says, “We should not underestimate the fact that this was possible through the interpretation of a huge amount of accumulated observations using a wide variety of means and methods, with an enormous amount of effort and time.”

However, it is “a period that seems similar to the slowness felt at a mature age.”

Therefore, at this time, it is crucial to look back on the past and present of physics, reflect on the limitations of human perception and science, and ask ourselves what remains to be done and what remains to be known.

It should be remembered that after the Big Bang model took hold, scientific optimism grew and expectations were high that the origin, structure, and matter of the universe would be elucidated, but conclusive evidence has not yet emerged.

We must ask ourselves whether science has lost its way, caught up in the arrogance of believing it has the answers to everything in the universe.

In that sense, this book is a self-reflective scientific book about our astrophysics, which has reached a period of stagnation (or maturity).

By organizing established ideas about the universe since the 20th century, addressing ideas that have reached a standstill since the turn of the century, and answering key questions challenging the authority of science today, we explore the current state of science and its future path toward the universe.

Part I explains how we came to believe that the universe exists in its current form, from the static model of the universe that even Einstein clung to to the dynamical model, through the discovery of general relativity and evidence of cosmic expansion. Part II explores the new landscape, where our understanding of physics is less certain and more incomplete.

We examine the still unresolved issues in astrophysics, such as the unknown matter and energy that make up the universe, its structure, origin, and rapid expansion.

Part III pauses the discussion to reflect on the difficulties that confound us and the limited, or perhaps permanent, limits of our knowledge of the universe.

It includes more fundamental questions about the universe, such as the dissonance between general relativity and quantum mechanics, the limit of observing the universe through light in the expanding universe (the cosmic horizon), and whether we can perceive the beginning and end of space-time.

And in Part VI of the book, we push the boundaries of what we know to the limit, challenging the very authority of scientific research.

By addressing the recurring questions that science has attempted to ignore, such as the multiverse, the existence of extraterrestrial life, and intelligent design, we will take time to reflect on the role of astrophysics and, furthermore, the limitations and challenges that science can address.

From the origins of space-time to the multiverse and the existence of extraterrestrial life

At the forefront of modern cosmology and astrophysics!

“The existence of a cosmic horizon is closely related to the fact that there is a limit to the time it takes for light (or any other signal) to travel through space.

So we can't go back further than 13.8 billion years in the Big Bang model.

On the other hand, if the universe were eternal and unchanging, there would be no horizon.

In this universe, at any moment, we can receive a signal from any random location far away, and this signal will travel long enough to reach us, even if it takes an incredibly long time.” _Main text p.

163 middle

Reading this book, you will experience a scientific narrative that beautifully blends science and humanities.

That is understandable, as it vividly captures the human joys and despair of physicists who tried to find rules in a universe full of unknowns that was created by chance.

The joy of knowing what there is to know about the universe suddenly turns into despair when you realize you know nothing, and then the true face of our science is shaking off that despair and trying again.

The author himself is a field astrophysicist who has dedicated himself to the model of rapid cosmic inflation and has experienced both joy and despair.

Thanks to this, as a scholar well-versed in the latest cosmology, he has a thorough understanding of what we know and what we don't know about the universe, including the standard cosmological model, and he explains this in a friendly manner at the reader's level.

We know what questions to ask about the universe, and we know how to find the answers to those questions.

Although the content is academic, the author has a thorough understanding of readers' interests and interests, thanks to his experience giving various public lectures and writing scientific books.

In particular, as you study the universe, you naturally become interested in the origins of humans and the universe, and as you do so, you cannot help but raise fundamental questions about the existence of humans and God. This book unfolds like a well-written humanities book, following the flow of thought.

This book is a rare bestseller among science books and is a work that is greatly loved by the Italian public.

In particular, it was evaluated as the best popular science work in Italy, including being selected as the winner of the 2021 Asimov Award (Premio Asimov 2021) hosted by the Italian government.

The Asimov Award is one of several awards created in memory of the famous writer and scientist Isaac Asimov, and is the most prestigious award in Italian science, awarded to the best popular science work edited in Italian.

What makes this award special is that it is a book that has been loved by many people, as it is decided by reading, reviewing, and voting directly by 10,000 high school students, high school teachers, researchers, graduate students, professors, and journalists from various fields.

In many ways, this is a very impressive book that is as fun to read as it is deep in content.

If you're wondering why so many Italians have chosen this book as their best science book, I invite you to take your time and enjoy the vast expanse of space together.

If so, has that limit already been reached?

We know the age of the universe very precisely, and we also know the matter and energy that make up the universe and its large-scale structure.

The physical systems that allowed the universe to evolve from an initially uncomplicated and simple state to the rich and complex state we inhabit today have also been identified.

But as we move toward the boundaries of space and time, we encounter problems that seriously challenge our tools and concepts.

Is the universe finite or infinite? Since space and time had a beginning, will they also have an end? Could the laws of nature have been different in the past? Are there other universes besides ours? Why is there something rather than nothing? _Main text p.

17

The James Webb Space Telescope, jointly developed and launched by the United States, the European Union, and others, is widely considered to have opened a new era in space observation by sending back better-than-expected results about stars and galaxies outside the solar system.

In fact, the incredibly realistic images that are being released one after another allow us to enjoy the wonders of the universe in a much more vivid way than the results sent back by Hubble, the best telescope ever.

Moreover, it is true that expectations are growing higher than ever that hints of extraterrestrial life, a long-held dream in astrophysics, may be discovered.

This is clearly a remarkable result of the scientific advancements that humanity has accumulated since the last century, and it deserves to be evaluated as another step forward for humanity in narrowing the boundaries of ignorance beyond the distant cosmic horizon and in understanding the universe shrouded in darkness.

However, if we consider whether modern astrophysics, which is developing so rapidly, is providing satisfactory answers to the questions we want to know about the universe, it becomes a slightly different question.

Strange as it may sound, although we are now inundated with a significant amount of high-quality new data, and very fine details of our existing picture of the universe have been reconstructed to a significant degree, the achievements of the last dozen years or so have not dramatically changed this overall picture of the universe since the turn of the century, when Einstein's general theory of relativity ushered in the 20th century and the Big Bang model was established to paint the overall picture of the universe.

What happened after the new millennium?

“It was disappointingly, surprisingly, nothing special,” says the book’s author, Italian astrophysicist Amedeo Balbi.

We still haven't figured out the beginning of the universe (inflation), just before it began expanding, and while we suspect there's dark matter that makes up most of the universe, we have no idea what it is.

The cosmological constant (dark energy) is the best option to explain the acceleration of the universe, but there are still doubts about its theoretical nature.

Beyond the cosmic horizon, we cannot know whether our universe is the only one or one of many, and we cannot be certain whether it is the only universe in this vast universe.

The worse news is that there's no guarantee that there will be light to illuminate the shadowy parts of that distant landscape.

Every time something seemingly small would come up, I held out hope that I would discover a new path, but when I dug deeper, nothing seemed meaningful.

Beyond the horizon where familiar territory ends,

What do we know and what do we not know?

Are there limits to what we can know about the universe? If so, have we already reached them? These questions are especially worth pondering when we feel we're drifting further and further from our destination, or when we encounter obstacles that seem insurmountable.

However, it should be borne in mind that the history of science has often fallen into two extreme situations.

The two are 'We will never know about the universe' and 'We already know everything there is to know.'

_From the introduction

So should we underestimate the immense effort we're making today to learn about the universe? Of course not.

The author says, “We should not underestimate the fact that this was possible through the interpretation of a huge amount of accumulated observations using a wide variety of means and methods, with an enormous amount of effort and time.”

However, it is “a period that seems similar to the slowness felt at a mature age.”

Therefore, at this time, it is crucial to look back on the past and present of physics, reflect on the limitations of human perception and science, and ask ourselves what remains to be done and what remains to be known.

It should be remembered that after the Big Bang model took hold, scientific optimism grew and expectations were high that the origin, structure, and matter of the universe would be elucidated, but conclusive evidence has not yet emerged.

We must ask ourselves whether science has lost its way, caught up in the arrogance of believing it has the answers to everything in the universe.

In that sense, this book is a self-reflective scientific book about our astrophysics, which has reached a period of stagnation (or maturity).

By organizing established ideas about the universe since the 20th century, addressing ideas that have reached a standstill since the turn of the century, and answering key questions challenging the authority of science today, we explore the current state of science and its future path toward the universe.

Part I explains how we came to believe that the universe exists in its current form, from the static model of the universe that even Einstein clung to to the dynamical model, through the discovery of general relativity and evidence of cosmic expansion. Part II explores the new landscape, where our understanding of physics is less certain and more incomplete.

We examine the still unresolved issues in astrophysics, such as the unknown matter and energy that make up the universe, its structure, origin, and rapid expansion.

Part III pauses the discussion to reflect on the difficulties that confound us and the limited, or perhaps permanent, limits of our knowledge of the universe.

It includes more fundamental questions about the universe, such as the dissonance between general relativity and quantum mechanics, the limit of observing the universe through light in the expanding universe (the cosmic horizon), and whether we can perceive the beginning and end of space-time.

And in Part VI of the book, we push the boundaries of what we know to the limit, challenging the very authority of scientific research.

By addressing the recurring questions that science has attempted to ignore, such as the multiverse, the existence of extraterrestrial life, and intelligent design, we will take time to reflect on the role of astrophysics and, furthermore, the limitations and challenges that science can address.

From the origins of space-time to the multiverse and the existence of extraterrestrial life

At the forefront of modern cosmology and astrophysics!

“The existence of a cosmic horizon is closely related to the fact that there is a limit to the time it takes for light (or any other signal) to travel through space.

So we can't go back further than 13.8 billion years in the Big Bang model.

On the other hand, if the universe were eternal and unchanging, there would be no horizon.

In this universe, at any moment, we can receive a signal from any random location far away, and this signal will travel long enough to reach us, even if it takes an incredibly long time.” _Main text p.

163 middle

Reading this book, you will experience a scientific narrative that beautifully blends science and humanities.

That is understandable, as it vividly captures the human joys and despair of physicists who tried to find rules in a universe full of unknowns that was created by chance.

The joy of knowing what there is to know about the universe suddenly turns into despair when you realize you know nothing, and then the true face of our science is shaking off that despair and trying again.

The author himself is a field astrophysicist who has dedicated himself to the model of rapid cosmic inflation and has experienced both joy and despair.

Thanks to this, as a scholar well-versed in the latest cosmology, he has a thorough understanding of what we know and what we don't know about the universe, including the standard cosmological model, and he explains this in a friendly manner at the reader's level.

We know what questions to ask about the universe, and we know how to find the answers to those questions.

Although the content is academic, the author has a thorough understanding of readers' interests and interests, thanks to his experience giving various public lectures and writing scientific books.

In particular, as you study the universe, you naturally become interested in the origins of humans and the universe, and as you do so, you cannot help but raise fundamental questions about the existence of humans and God. This book unfolds like a well-written humanities book, following the flow of thought.

This book is a rare bestseller among science books and is a work that is greatly loved by the Italian public.

In particular, it was evaluated as the best popular science work in Italy, including being selected as the winner of the 2021 Asimov Award (Premio Asimov 2021) hosted by the Italian government.

The Asimov Award is one of several awards created in memory of the famous writer and scientist Isaac Asimov, and is the most prestigious award in Italian science, awarded to the best popular science work edited in Italian.

What makes this award special is that it is a book that has been loved by many people, as it is decided by reading, reviewing, and voting directly by 10,000 high school students, high school teachers, researchers, graduate students, professors, and journalists from various fields.

In many ways, this is a very impressive book that is as fun to read as it is deep in content.

If you're wondering why so many Italians have chosen this book as their best science book, I invite you to take your time and enjoy the vast expanse of space together.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: October 14, 2022

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 304 pages | 460g | 128*188*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791197617041

- ISBN10: 1197617043

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)