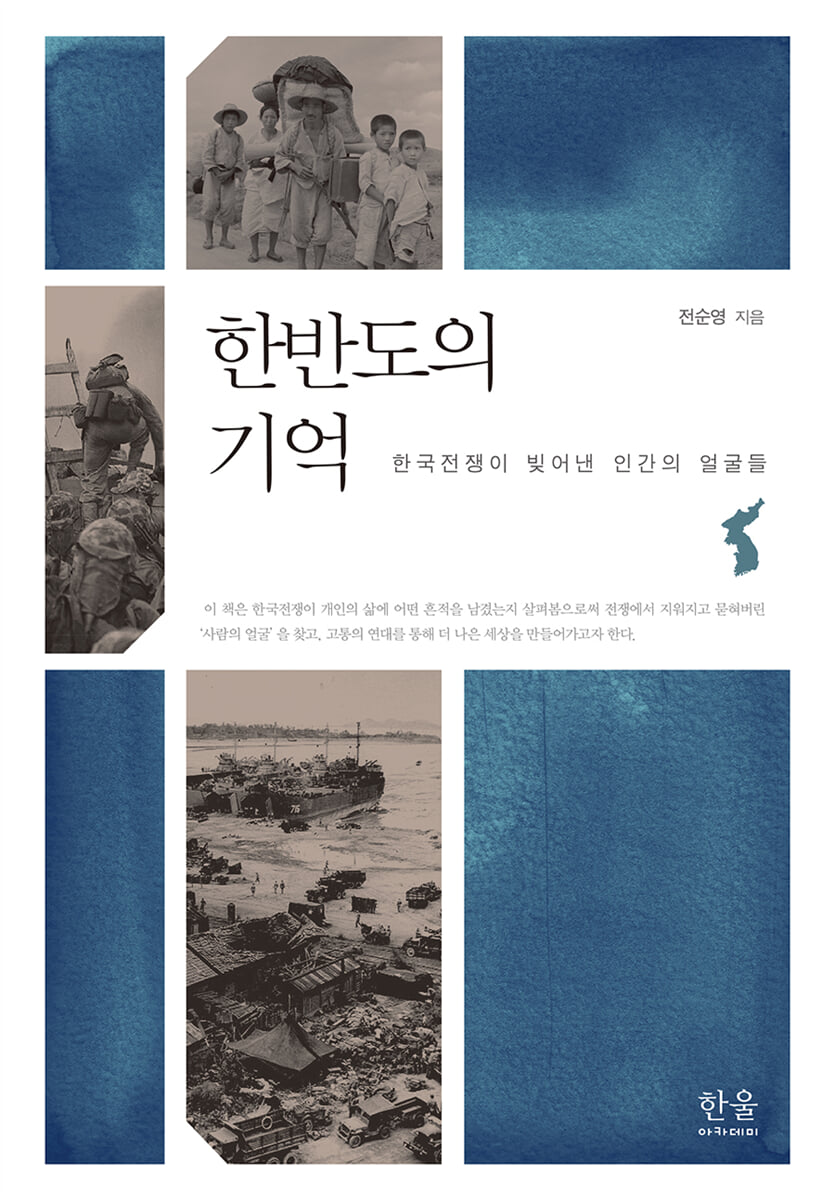

Memories of the Korean Peninsula

|

Description

Book Introduction

The scars left on us by the Korean War

A book that reconciles and reconstructs cultural memory

This book diagnoses that Korean society still suffers from the memory of war, and attempts to re-memorize the war as a treatment method, exploring the possibility of post-traumatic growth through this process.

How we remember the war is directly related to the identity of the Republic of Korea.

Therefore, the author argues that we should not simply divide war into perpetrators and victims, but rather acknowledge and accept the different levels of war memory.

He also emphasizes that while remembering the war that caused trauma, the goal of rememorization should be the advancement of justice and peace, freedom and democracy, the improvement of human rights, and the growth of members of society.

This book blends sociological and humanistic perspectives to reconcile memories of the Korean War.

In particular, to delve into the more microscopic aspects of war, he borrows heavily from personal narratives such as novels and memoirs, and cites various artistic genres such as poetry, song, film, and theater.

This book examines the marks the Korean War left on individual lives, seeking to uncover the "human faces" erased and buried by the war and, through solidarity in suffering, to create a better world.

A book that reconciles and reconstructs cultural memory

This book diagnoses that Korean society still suffers from the memory of war, and attempts to re-memorize the war as a treatment method, exploring the possibility of post-traumatic growth through this process.

How we remember the war is directly related to the identity of the Republic of Korea.

Therefore, the author argues that we should not simply divide war into perpetrators and victims, but rather acknowledge and accept the different levels of war memory.

He also emphasizes that while remembering the war that caused trauma, the goal of rememorization should be the advancement of justice and peace, freedom and democracy, the improvement of human rights, and the growth of members of society.

This book blends sociological and humanistic perspectives to reconcile memories of the Korean War.

In particular, to delve into the more microscopic aspects of war, he borrows heavily from personal narratives such as novels and memoirs, and cites various artistic genres such as poetry, song, film, and theater.

This book examines the marks the Korean War left on individual lives, seeking to uncover the "human faces" erased and buried by the war and, through solidarity in suffering, to create a better world.

index

Chapter 1: Why the Korean War Again Now?

Chapter 2: Trauma on the Korean Peninsula

Chapter 3: Memory of Historical Trauma

Chapter 4: What Did the Korean War Mean to Us?

Chapter 5: The Human Faces of War

Chapter 6: The Korean War as Experienced by Foreigners

Chapter 7: North Korean Society's Memories of War

Chapter 8: Living Together on the Korean Peninsula

Chapter 2: Trauma on the Korean Peninsula

Chapter 3: Memory of Historical Trauma

Chapter 4: What Did the Korean War Mean to Us?

Chapter 5: The Human Faces of War

Chapter 6: The Korean War as Experienced by Foreigners

Chapter 7: North Korean Society's Memories of War

Chapter 8: Living Together on the Korean Peninsula

Into the book

Narrating the lives of individuals amid the tragedy of war and the devastation of nationalism is an area where literature excels.

For example, a series of literary works about guerrillas published in the mid-to-late 1980s, such as Lee Byeong-ju's "Jirisan," Jo Jeong-rae's "Taebaeksanmaek," and Lee Tae's "Nambugun," are evaluated to have had a significant influence on forming the public's perception of guerrillas.

…Therefore, this book will cite relevant literary works relatively frequently within the structural context of division.

This includes texts produced by others on the subject of the Korean War, namely literary works related to the Korean War existing in the United States, Japan, China, Turkey, etc.

--- p.41

Only humans commit violence that dehumanizes other humans.

If the essence of unification is the ‘unification of people,’ then the essence of division also lies in the ‘division of people.’

The division of the Korean Peninsula is deeply engraved in the hearts of everyone living on the peninsula in this era.

The language of fear, anxiety, hatred and anger still overflows on the Internet and in public squares.

Therefore, individual responses are important.

We need to recognize that we are the ones who have suffered historical trauma, and that overcoming trauma also begins with us.

This is why forgiveness and reconciliation must have a personal dimension.

--- p.105~106

The South and the North are threatening each other and heightening the crisis of war through joint military exercises and strengthening nuclear weapons 'for the sake of peace.'

Is this the right path to peace? Those who take the sword will perish by the sword.

The effort to establish, create, and maintain peace is the surest means of preparing for war.

Rather than simply focusing on a passive peace—the absence of war—we must strive to actively control fear, hostility, tension, and conflict between individuals and groups by concretely realizing a positive peace in which structural and cultural violence are eliminated.

Both the South and the North are suffering from the trauma of the Korean War, and the perspective that we are all victims in the face of history can be part of such efforts.

--- p.152

Christians should not simply interpret the sacrifices of their predecessors as religious martyrdom, but should remember the face of the reconciler who demonstrated practical reconciliation in his efforts to respect life and restore community.

They have abundant religious resources to become 'righteous neighbors'.

If the church can become a community of remembrance for reconciliation, as the West German church did during the reunification process, Christians will be able to assume social responsibility as important civic actors in realizing future social integration.

--- p.284

One possible reason for this difference in educational content is that South Korea, having achieved high economic growth after the war, does not remember the pain of war much, whereas North Korea still has fear and a sense of crisis because everything is tied to war.

When people become well-off, they don't often recall difficult times in the past, and even if they do, they don't recall them in a way that constantly brings up past pain.

The fact that North Korea is trying to instill extreme hatred in its people means that it has not yet been able to escape the persistent sense of victimization caused by memories of the past war.

The obsession of top leaders with developing nuclear weapons is difficult to explain in any other way.

--- p.337

Looking at the process of clearing away historical remnants over the long years since the American Civil War, South Africa's apartheid, and the end of the Spanish dictatorship, it can be predicted that it will take a long time to heal the wounds of the Korean War, April 3, and May 18.

Leadership of forgiveness and reconciliation is crucial to alleviating and overcoming deep-seated hatred and conflict.

Kim Dae-jung, who suffered extreme persecution under the Yushin regime and was sentenced to death under the Chun Doo-hwan regime, avoided retaliation and pursued a policy of reconciliation and unification after being elected president.

He decided to support the construction of the President Park Chung-hee Memorial Hall in 1999.

--- p.420

If the past is to help the present, if the dead are to save the living, we must remember correctly.

Just as the memory of May 18th prevented the December 3rd martial law.

Therefore, the answer to Han Kang's question would be, "It depends on our conscience."

The duty to ensure that memory becomes salvation lies with the living.

The memory of the Korean Peninsula is the identity of its people.

What kind of identity do we want to pass on to the next generation?

For example, a series of literary works about guerrillas published in the mid-to-late 1980s, such as Lee Byeong-ju's "Jirisan," Jo Jeong-rae's "Taebaeksanmaek," and Lee Tae's "Nambugun," are evaluated to have had a significant influence on forming the public's perception of guerrillas.

…Therefore, this book will cite relevant literary works relatively frequently within the structural context of division.

This includes texts produced by others on the subject of the Korean War, namely literary works related to the Korean War existing in the United States, Japan, China, Turkey, etc.

--- p.41

Only humans commit violence that dehumanizes other humans.

If the essence of unification is the ‘unification of people,’ then the essence of division also lies in the ‘division of people.’

The division of the Korean Peninsula is deeply engraved in the hearts of everyone living on the peninsula in this era.

The language of fear, anxiety, hatred and anger still overflows on the Internet and in public squares.

Therefore, individual responses are important.

We need to recognize that we are the ones who have suffered historical trauma, and that overcoming trauma also begins with us.

This is why forgiveness and reconciliation must have a personal dimension.

--- p.105~106

The South and the North are threatening each other and heightening the crisis of war through joint military exercises and strengthening nuclear weapons 'for the sake of peace.'

Is this the right path to peace? Those who take the sword will perish by the sword.

The effort to establish, create, and maintain peace is the surest means of preparing for war.

Rather than simply focusing on a passive peace—the absence of war—we must strive to actively control fear, hostility, tension, and conflict between individuals and groups by concretely realizing a positive peace in which structural and cultural violence are eliminated.

Both the South and the North are suffering from the trauma of the Korean War, and the perspective that we are all victims in the face of history can be part of such efforts.

--- p.152

Christians should not simply interpret the sacrifices of their predecessors as religious martyrdom, but should remember the face of the reconciler who demonstrated practical reconciliation in his efforts to respect life and restore community.

They have abundant religious resources to become 'righteous neighbors'.

If the church can become a community of remembrance for reconciliation, as the West German church did during the reunification process, Christians will be able to assume social responsibility as important civic actors in realizing future social integration.

--- p.284

One possible reason for this difference in educational content is that South Korea, having achieved high economic growth after the war, does not remember the pain of war much, whereas North Korea still has fear and a sense of crisis because everything is tied to war.

When people become well-off, they don't often recall difficult times in the past, and even if they do, they don't recall them in a way that constantly brings up past pain.

The fact that North Korea is trying to instill extreme hatred in its people means that it has not yet been able to escape the persistent sense of victimization caused by memories of the past war.

The obsession of top leaders with developing nuclear weapons is difficult to explain in any other way.

--- p.337

Looking at the process of clearing away historical remnants over the long years since the American Civil War, South Africa's apartheid, and the end of the Spanish dictatorship, it can be predicted that it will take a long time to heal the wounds of the Korean War, April 3, and May 18.

Leadership of forgiveness and reconciliation is crucial to alleviating and overcoming deep-seated hatred and conflict.

Kim Dae-jung, who suffered extreme persecution under the Yushin regime and was sentenced to death under the Chun Doo-hwan regime, avoided retaliation and pursued a policy of reconciliation and unification after being elected president.

He decided to support the construction of the President Park Chung-hee Memorial Hall in 1999.

--- p.420

If the past is to help the present, if the dead are to save the living, we must remember correctly.

Just as the memory of May 18th prevented the December 3rd martial law.

Therefore, the answer to Han Kang's question would be, "It depends on our conscience."

The duty to ensure that memory becomes salvation lies with the living.

The memory of the Korean Peninsula is the identity of its people.

What kind of identity do we want to pass on to the next generation?

--- p.446

Publisher's Review

Memory Research to Overcome the Wounds and Historical Trauma of the Korean Peninsula

Currently, South Korea is experiencing extreme conflict between various ideological groups, including progressives and conservatives.

But at the heart of that ideological landscape still lies a conflicting view of North Korea.

This book explores the traces the Korean War left on individual lives, while also seeking to heal the trauma of war by reviving and remembering the pain inherent in both North and South Korea.

In this book, the author argues that the Korean War should not be divided into perpetrators and victims, but rather that we should acknowledge and accept the different memories of the war.

This book proposes that, as a way to overcome trauma, one should integrate it into one's own and one's group identity and connect the meaning of one's suffering to higher values. It emphasizes that, in order to achieve this kind of post-traumatic growth, one must first uncover historical truth and establish a foundation for achieving justice.

The unique feature of this book is that it confronts the wounds left by the Korean War and attempts to re-memorize the war.

In this process, we mainly use cultural memories reproduced in various artistic genres such as poetry, song, film, and play.

This is because 'Human Memories', recorded in literature rather than in official documents or media articles, go even further down to the microscopic level of war and society and tell the story of 'war and people.'

In this way, this book blends sociological and humanistic perspectives by citing literary works related to the structural context of division and borrowing personal narratives such as novels and memoirs.

Reconstructing the Korean War through Literature and Cultural Memory

According to this book, historical trauma is a phenomenon that appears in societies that have experienced structural, collective, and long-term violence, and has the characteristic of being passed down to future generations and even to those who did not directly experience it.

Therefore, it takes a very long time to heal historical trauma.

This book emphasizes that collective memory is passed down as cultural memory, and therefore efforts are needed to change cultural memory, or commemorative culture.

The Korean War taught us the lesson that pursuing unification by force carries a high price and sacrifice.

The scars left by the Korean War are irreparably deep and have lasted for generations.

Therefore, unification must be pursued with peace as its goal and through peaceful means.

The author emphasizes that resolving internal differences and conflicts through compromise and coexistence is the way to build peace and prepare for unification by raising the level and capacity of a democratic society.

The author, who majored in Christian Unification Leadership Studies, has conducted sociological research on North Korea, unification, and North Korean defectors, while also working on humanistic research on transitional justice, forgiveness and reconciliation, trauma healing, and conflict transformation.

In this book, the author explores ways to liberate the memories of each individual who has been nationally, socially, and culturally suppressed for a long time due to the Korean War and to move toward a path of coexistence.

Currently, South Korea is experiencing extreme conflict between various ideological groups, including progressives and conservatives.

But at the heart of that ideological landscape still lies a conflicting view of North Korea.

This book explores the traces the Korean War left on individual lives, while also seeking to heal the trauma of war by reviving and remembering the pain inherent in both North and South Korea.

In this book, the author argues that the Korean War should not be divided into perpetrators and victims, but rather that we should acknowledge and accept the different memories of the war.

This book proposes that, as a way to overcome trauma, one should integrate it into one's own and one's group identity and connect the meaning of one's suffering to higher values. It emphasizes that, in order to achieve this kind of post-traumatic growth, one must first uncover historical truth and establish a foundation for achieving justice.

The unique feature of this book is that it confronts the wounds left by the Korean War and attempts to re-memorize the war.

In this process, we mainly use cultural memories reproduced in various artistic genres such as poetry, song, film, and play.

This is because 'Human Memories', recorded in literature rather than in official documents or media articles, go even further down to the microscopic level of war and society and tell the story of 'war and people.'

In this way, this book blends sociological and humanistic perspectives by citing literary works related to the structural context of division and borrowing personal narratives such as novels and memoirs.

Reconstructing the Korean War through Literature and Cultural Memory

According to this book, historical trauma is a phenomenon that appears in societies that have experienced structural, collective, and long-term violence, and has the characteristic of being passed down to future generations and even to those who did not directly experience it.

Therefore, it takes a very long time to heal historical trauma.

This book emphasizes that collective memory is passed down as cultural memory, and therefore efforts are needed to change cultural memory, or commemorative culture.

The Korean War taught us the lesson that pursuing unification by force carries a high price and sacrifice.

The scars left by the Korean War are irreparably deep and have lasted for generations.

Therefore, unification must be pursued with peace as its goal and through peaceful means.

The author emphasizes that resolving internal differences and conflicts through compromise and coexistence is the way to build peace and prepare for unification by raising the level and capacity of a democratic society.

The author, who majored in Christian Unification Leadership Studies, has conducted sociological research on North Korea, unification, and North Korean defectors, while also working on humanistic research on transitional justice, forgiveness and reconciliation, trauma healing, and conflict transformation.

In this book, the author explores ways to liberate the memories of each individual who has been nationally, socially, and culturally suppressed for a long time due to the Korean War and to move toward a path of coexistence.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 5, 2025

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 472 pages | 153*224*10mm

- ISBN13: 9788946075948

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)