Whose sentence is this?

|

Description

Book Introduction

How Copyright Became the World's Greatest Money-Making Machine

From publishing to how copyright took on its present form

A copyright story full of dramatic twists! - The Economist

A surprisingly quirky history book that arrives at a strange time - Alexandra Jacobs, The New York Times

Let's look around.

Novels and poems on the bookshelf, videos on your smartphone, music heard on the street, posters on bulletin boards, character dolls bought as travel souvenirs…

Today, we live surrounded by intangible content.

In an age overflowing with content, intangible creations move money and the world.

Who owns all these intangible assets? Who has the right to their profits? After Gutenberg's invention of movable metal type, printers monopolized the distribution of books and knowledge.

In 18th century England, laws were enacted to prevent their monopolization of knowledge.

This law guaranteed copyright holders the right to their works for 28 years after publication, which was the birth of copyright in the modern sense, and the concept of copyright has undergone many changes since then.

Beyond published texts, even sounds and personalities have become subject to copyright, and the copyright protection period has been extended for various reasons.

Copyright has now become a complex and intensified means of profiteering, granting exclusive rights to many companies.

Copyright was established in its current form through the vested interests and legal battles of numerous groups.

"Whose Sentence Does This Own?" tells the fascinating story of copyright history, tracing its evolution from its birth to the present day.

This book examines the flow of copyright, one of the important rights that drives today's society.

From publishing to how copyright took on its present form

A copyright story full of dramatic twists! - The Economist

A surprisingly quirky history book that arrives at a strange time - Alexandra Jacobs, The New York Times

Let's look around.

Novels and poems on the bookshelf, videos on your smartphone, music heard on the street, posters on bulletin boards, character dolls bought as travel souvenirs…

Today, we live surrounded by intangible content.

In an age overflowing with content, intangible creations move money and the world.

Who owns all these intangible assets? Who has the right to their profits? After Gutenberg's invention of movable metal type, printers monopolized the distribution of books and knowledge.

In 18th century England, laws were enacted to prevent their monopolization of knowledge.

This law guaranteed copyright holders the right to their works for 28 years after publication, which was the birth of copyright in the modern sense, and the concept of copyright has undergone many changes since then.

Beyond published texts, even sounds and personalities have become subject to copyright, and the copyright protection period has been extended for various reasons.

Copyright has now become a complex and intensified means of profiteering, granting exclusive rights to many companies.

Copyright was established in its current form through the vested interests and legal battles of numerous groups.

"Whose Sentence Does This Own?" tells the fascinating story of copyright history, tracing its evolution from its birth to the present day.

This book examines the flow of copyright, one of the important rights that drives today's society.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Part 1: The Birth of Copyright

Chapter 1: The Meaning of Copyright

Chapter 2: Ancient Authors

Chapter 3: Patents and Privileges in Renaissance Italy

Chapter 4 Ownership and Responsibility

Chapter 5 Books Before Copyright

Chapter 6 Where do property rights come from?

Chapter 7: A Brief History of Genius

Chapter 8 Queen Anne's Statute

Chapter 9: The Illusion of the Incentive Effect

Chapter 10: 18th-Century French Writers

Chapter 11 Failed Resistance

Part 2 What is original expression?

Chapter 12 The Fog of Law

Chapter 13: Expansion of Copyright Law

Chapter 14: The Copyright Struggle

Chapter 15 Revolutionary Changes in France and the United States

Chapter 16: Romanticism and Copyright

Chapter 17 Literary Heritage

Chapter 18 Copyright in Plays and Films

Chapter 19: 19th-Century America: A Piracy Paradise

Chapter 20: International Copyright Competition

Chapter 21 Berne Convention of 1886

Chapter 22: Copyright Revived

Chapter 23: Posthumous Copyright Debate

Chapter 24: The United States and the Soviet Union in the 20th Century

Chapter 25 Copyright of Corporations

Part 3: The Flood of Copyright

Chapter 26: Whose Facts Are They?

Chapter 27: Ideas and Expression

Chapter 28 Is My Face My Own?

Chapter 29: The Power of Personal Rights

Chapter 30: Sound Story

Chapter 31: United States Copyright Act of 1976

Chapter 32 Fair Use

Chapter 33: Copyright Panic

Chapter 34: Promoting Copyright with False Information

Chapter 35 Orphan Works

Chapter 36: Boundaries of the Protected Area

Chapter 37 Copyright in China

Part 4: Standing at a Crossroads

Chapter 38: Copyright Exceeding the Limit

Chapter 39 Copyright Distortion

Chapter 40: The Rise and Fall of Transformational Use

Chapter 41 Creative Commons

Chapter 42: The World's Largest ATM

Chapter 43: Current Status of Copyright

Chapter 44: What if…

References

Americas

Chapter 1: The Meaning of Copyright

Chapter 2: Ancient Authors

Chapter 3: Patents and Privileges in Renaissance Italy

Chapter 4 Ownership and Responsibility

Chapter 5 Books Before Copyright

Chapter 6 Where do property rights come from?

Chapter 7: A Brief History of Genius

Chapter 8 Queen Anne's Statute

Chapter 9: The Illusion of the Incentive Effect

Chapter 10: 18th-Century French Writers

Chapter 11 Failed Resistance

Part 2 What is original expression?

Chapter 12 The Fog of Law

Chapter 13: Expansion of Copyright Law

Chapter 14: The Copyright Struggle

Chapter 15 Revolutionary Changes in France and the United States

Chapter 16: Romanticism and Copyright

Chapter 17 Literary Heritage

Chapter 18 Copyright in Plays and Films

Chapter 19: 19th-Century America: A Piracy Paradise

Chapter 20: International Copyright Competition

Chapter 21 Berne Convention of 1886

Chapter 22: Copyright Revived

Chapter 23: Posthumous Copyright Debate

Chapter 24: The United States and the Soviet Union in the 20th Century

Chapter 25 Copyright of Corporations

Part 3: The Flood of Copyright

Chapter 26: Whose Facts Are They?

Chapter 27: Ideas and Expression

Chapter 28 Is My Face My Own?

Chapter 29: The Power of Personal Rights

Chapter 30: Sound Story

Chapter 31: United States Copyright Act of 1976

Chapter 32 Fair Use

Chapter 33: Copyright Panic

Chapter 34: Promoting Copyright with False Information

Chapter 35 Orphan Works

Chapter 36: Boundaries of the Protected Area

Chapter 37 Copyright in China

Part 4: Standing at a Crossroads

Chapter 38: Copyright Exceeding the Limit

Chapter 39 Copyright Distortion

Chapter 40: The Rise and Fall of Transformational Use

Chapter 41 Creative Commons

Chapter 42: The World's Largest ATM

Chapter 43: Current Status of Copyright

Chapter 44: What if…

References

Americas

Into the book

Copyright originated in London in the early 18th century.

The first form was to grant a short-term monopoly on the printing and sale of books to the author and his assignees.

The scope of such monopolies grew over the centuries that followed, and the number of years for which they could be monopolized also increased.

Afterwards, the scope of copyright gradually expanded to include secondary uses such as abbreviations, adaptations, performances, and translations.

At each stage, there was resistance, but we slowly advanced and expanded our power.

The philosophical, ethical, and practical arguments for stopping copyright have never worked.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Meaning of Copyright"

As this famous writer's painful experience shows, those who "own" a work should naturally be able to "own" the rights to it by being punished for works that violate the prevailing consensus.

That means you have to take that profit.

-Page 49, Chapter 4 Ownership and Responsibility

Wallace's Circus printed thousands of such posters through George Bleistein's Courier lithograph shop.

But when the stock ran out, Wallace Circus ordered identical posters from Donaldson Lithograph, a competitor to Courier.

Bleistein was furious and sued Donaldson for copyright infringement.

There were two issues at stake, along with a large sum of money.

First, can a company, not an individual, own copyright?

Second, is it really true that circus posters are appropriate subjects for copyright protection?

--- From "Chapter 19: America in the 19th Century: A Paradise for Piracy"

In theory (and it is quite possible in practice), this is how the law works:

If a historian discovers that your long-forgotten grandmother was a resistance hero and becomes the subject of a fascinating book, you should fly to Guernsey and register her identity immediately.

Then, you could make a nice income by charging royalties to people who want to include your grandmother's old photos in books or on websites, or to reproduce them in movies or on T-shirts.

--- From "Chapter 28 Is My Face Mine?"

The primary sources that AI frequently encounters for "learning" or "training"—images, audio, information databases—are largely copyrighted. Therefore, the development of new AI tools will usher in a new era of copyright litigation, and even if not the AI itself, its output could be embroiled in copyright infringement allegations.

It remains to be seen whether existing copyright systems, created in different eras and for different media, can resolve new types of disputes, or whether AI can overcome the current system's obstacles.

The first form was to grant a short-term monopoly on the printing and sale of books to the author and his assignees.

The scope of such monopolies grew over the centuries that followed, and the number of years for which they could be monopolized also increased.

Afterwards, the scope of copyright gradually expanded to include secondary uses such as abbreviations, adaptations, performances, and translations.

At each stage, there was resistance, but we slowly advanced and expanded our power.

The philosophical, ethical, and practical arguments for stopping copyright have never worked.

--- From "Chapter 1: The Meaning of Copyright"

As this famous writer's painful experience shows, those who "own" a work should naturally be able to "own" the rights to it by being punished for works that violate the prevailing consensus.

That means you have to take that profit.

-Page 49, Chapter 4 Ownership and Responsibility

Wallace's Circus printed thousands of such posters through George Bleistein's Courier lithograph shop.

But when the stock ran out, Wallace Circus ordered identical posters from Donaldson Lithograph, a competitor to Courier.

Bleistein was furious and sued Donaldson for copyright infringement.

There were two issues at stake, along with a large sum of money.

First, can a company, not an individual, own copyright?

Second, is it really true that circus posters are appropriate subjects for copyright protection?

--- From "Chapter 19: America in the 19th Century: A Paradise for Piracy"

In theory (and it is quite possible in practice), this is how the law works:

If a historian discovers that your long-forgotten grandmother was a resistance hero and becomes the subject of a fascinating book, you should fly to Guernsey and register her identity immediately.

Then, you could make a nice income by charging royalties to people who want to include your grandmother's old photos in books or on websites, or to reproduce them in movies or on T-shirts.

--- From "Chapter 28 Is My Face Mine?"

The primary sources that AI frequently encounters for "learning" or "training"—images, audio, information databases—are largely copyrighted. Therefore, the development of new AI tools will usher in a new era of copyright litigation, and even if not the AI itself, its output could be embroiled in copyright infringement allegations.

It remains to be seen whether existing copyright systems, created in different eras and for different media, can resolve new types of disputes, or whether AI can overcome the current system's obstacles.

--- From "Chapter 43: Current Status of Copyright"

Publisher's Review

The work was not the author's?

I'm planning to include a movie review in my new book.

But can I include a screenshot? What about the lyrics of the inserted song? I'm starting to become conscious of copyright.

Who should I contact? I'm even thinking about finding the author and contacting them.

In this way, we naturally become conscious of copyright when using other people's works.

But since when has this idea become so obvious? The rights to creative works belong to the creator.

Creative works are the property of their creators, and using someone else's creative work without permission is tantamount to stealing.

This concept, which is common sense today, did not exist from the beginning.

Authors in ancient Greece had the right to decide when and how to publish their works, and while others published their works without permission and caused controversy, redistribution of published works was not a problem.

Plagiarism and theft were only criticized as ethical issues when the source was not properly acknowledged.

After Gutenberg invented metal type and printers began printing books, the rights to published texts were given to printers.

Printers with monopolies controlled the distribution of works by famous authors and prevented others from printing books with the same content elsewhere.

In the 18th century, England enacted laws to limit their monopoly, which gave the copyright to their works to the authors.

It was not until the 18th century that copyright in the modern sense emerged.

Afterwards, a law was created in France guaranteeing the author the rights to his or her work for life, and the concept that "original works are the property of the author" gradually spread throughout the world.

Guaranteeing more, longer, for businesses

"Whose Sentence Does This Belong To?" vividly traces the process by which the concept of copyright grew in size.

The popular British printmaker Hogarth submitted a petition to Parliament, stating that prints were also printed matter, and prints, not just text, were also included in the scope of copyright protection.

Afterwards, posters, which are publications produced by printing houses, were also included in the scope of protection, and it expanded to include records, music, characters, and programs.

Additionally, the period, which was initially 28 years after publication, was extended to 10 years after the author's death for the author's family.

In Russia, the period of copyright protection was extended to 50 years after death in the mid-19th century at the request of Pushkin's wife, and many countries now protect copyright for 70 years after death.

Now, most countries, except for about ten, have joined the Berne Convention, an international cooperation for copyright protection.

In this way, other noises arose during the process of copyright change.

Contrary to its original intention of preventing monopolies by multiple companies and protecting the rights of creators, the strengthened copyright law has now become a sword for the large corporations of powerful countries.

More than a quarter of global licensing fees flow into the United States, exacerbating inequality between countries.

Meanwhile, most works published today are destined to become 'orphan works' whose creators cannot be found.

Orphan works are works whose authorship cannot be found even if the corporation that created them goes out of business or the author dies without children.

Ninety percent of works published in the last century have become orphans, and discussions about them are often halted because permission to reuse them is not granted.

As we explore the history of copyright, guided by the authors, we are forced to question concepts we take for granted.

If different conclusions had been reached at various junctures surrounding copyright, the landscape of copyright would be different today.

Copyright has become much more powerful and complex, but it still has its share of ambiguities.

By hearing various stories surrounding copyright, readers will be able to look at copyright in a new way.

I'm planning to include a movie review in my new book.

But can I include a screenshot? What about the lyrics of the inserted song? I'm starting to become conscious of copyright.

Who should I contact? I'm even thinking about finding the author and contacting them.

In this way, we naturally become conscious of copyright when using other people's works.

But since when has this idea become so obvious? The rights to creative works belong to the creator.

Creative works are the property of their creators, and using someone else's creative work without permission is tantamount to stealing.

This concept, which is common sense today, did not exist from the beginning.

Authors in ancient Greece had the right to decide when and how to publish their works, and while others published their works without permission and caused controversy, redistribution of published works was not a problem.

Plagiarism and theft were only criticized as ethical issues when the source was not properly acknowledged.

After Gutenberg invented metal type and printers began printing books, the rights to published texts were given to printers.

Printers with monopolies controlled the distribution of works by famous authors and prevented others from printing books with the same content elsewhere.

In the 18th century, England enacted laws to limit their monopoly, which gave the copyright to their works to the authors.

It was not until the 18th century that copyright in the modern sense emerged.

Afterwards, a law was created in France guaranteeing the author the rights to his or her work for life, and the concept that "original works are the property of the author" gradually spread throughout the world.

Guaranteeing more, longer, for businesses

"Whose Sentence Does This Belong To?" vividly traces the process by which the concept of copyright grew in size.

The popular British printmaker Hogarth submitted a petition to Parliament, stating that prints were also printed matter, and prints, not just text, were also included in the scope of copyright protection.

Afterwards, posters, which are publications produced by printing houses, were also included in the scope of protection, and it expanded to include records, music, characters, and programs.

Additionally, the period, which was initially 28 years after publication, was extended to 10 years after the author's death for the author's family.

In Russia, the period of copyright protection was extended to 50 years after death in the mid-19th century at the request of Pushkin's wife, and many countries now protect copyright for 70 years after death.

Now, most countries, except for about ten, have joined the Berne Convention, an international cooperation for copyright protection.

In this way, other noises arose during the process of copyright change.

Contrary to its original intention of preventing monopolies by multiple companies and protecting the rights of creators, the strengthened copyright law has now become a sword for the large corporations of powerful countries.

More than a quarter of global licensing fees flow into the United States, exacerbating inequality between countries.

Meanwhile, most works published today are destined to become 'orphan works' whose creators cannot be found.

Orphan works are works whose authorship cannot be found even if the corporation that created them goes out of business or the author dies without children.

Ninety percent of works published in the last century have become orphans, and discussions about them are often halted because permission to reuse them is not granted.

As we explore the history of copyright, guided by the authors, we are forced to question concepts we take for granted.

If different conclusions had been reached at various junctures surrounding copyright, the landscape of copyright would be different today.

Copyright has become much more powerful and complex, but it still has its share of ambiguities.

By hearing various stories surrounding copyright, readers will be able to look at copyright in a new way.

GOODS SPECIFICS

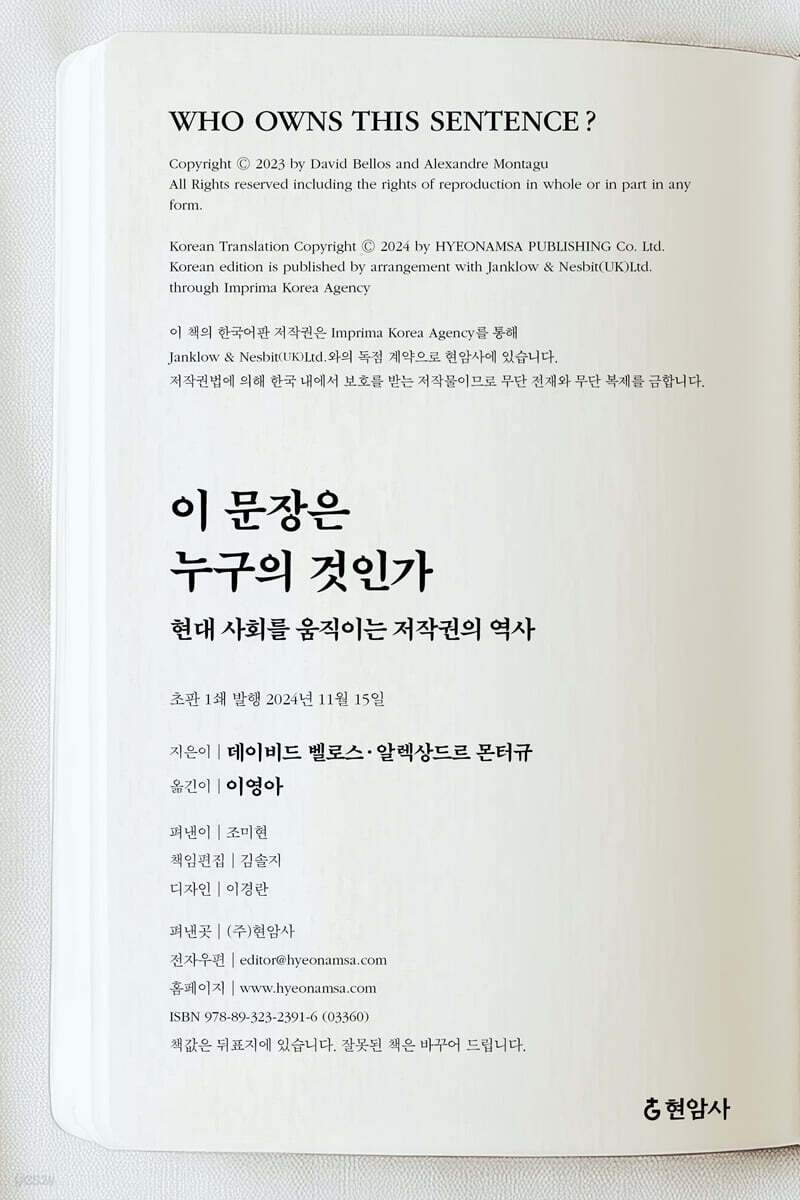

- Date of issue: November 15, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 404 pages | 504g | 140*210*19mm

- ISBN13: 9788932323916

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)