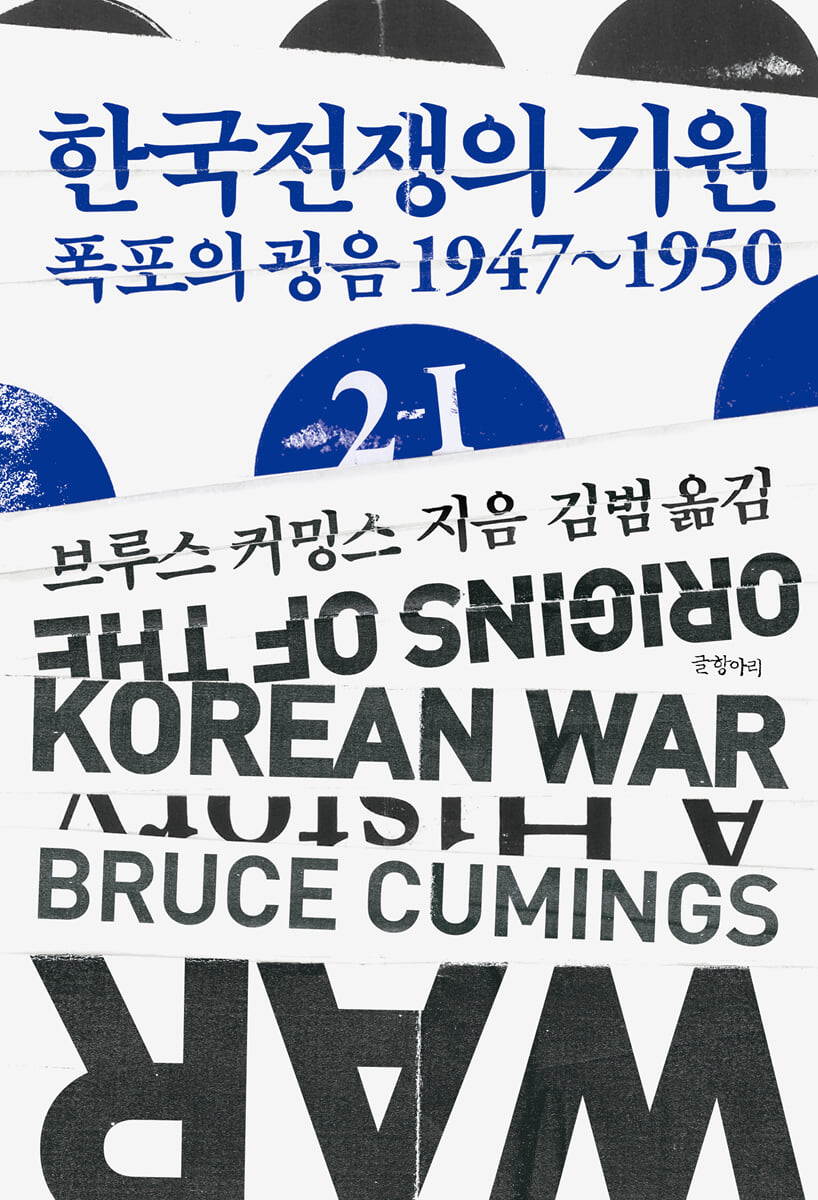

The Origins of the Korean War 2-Ⅰ

|

Description

index

Preface to the Korean edition

preface

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Book ─ A Review of the Methods and Theories of American Foreign Policy

Science and Mystery: "The Problem of Highly Nonlinear and Unstable Liberal Borders" | Toward a Theory of American Foreign Policy | Incomprehensible Incrementalism and the American Egg | The State as the Purpose and Consequence of Class Struggle | Rulers and Interest Powers | International Cooperationism/Imperialism and Expansionism/Nationalism | Elements of American Foreign Policy: International Cooperationism, Containment, and Counterattack

Part 1: United States

Chapter 2: Blockade and International Cooperation

Politician Acheson | "The Great Crescent": The Acheson Line | Kennan's Engineering | The Politics of Strategy: The State Department and the War Department's Conflicts Over Korea | The Syngman Rhee Lobby in Washington: "I'm in Trouble Because of Syngman Rhee's Folly" | The UN as a Compromise | The Second US-Soviet Joint Commission | The UN and the 1948 Election

Chapter 3: Counterattack and Nationalism

Rethinking American Nationalism: The Politics and Economics of Isolationism/Counteroffensive | Expansionism and Minerals | Counteroffensives and Airpower | MacArthur and Willoughby: Local Counteroffensive Commands | The China Lobby, McCarthyism, and Counteroffensive | James Burnham: The Theorist of Interventionism

Chapter 4: Destiny to Enter the Predestined Labyrinth: Spies and Speculators

Central Intelligence Agency | Donovan's Cold War Stronghold | Unofficial Partners in East Asia: Chenault, Foley, Willow, Cook, and Other Key Figures | Goodfellow's Special Mission | Mole in the Maze: Britain's Spy | All the Gold: Gold, Tungsten, Black Sand, and Soybeans | Soybean Price Manipulation | Conclusion

Chapter 5: The Counterattack that Infiltrated the Bureaucracy

Containment and Counterattack: Relations with Japan | The Expanding Crescent | The Japanese Lobby and US Policy | Containment and Counterattack in National Security Council Document 68 | Conclusion

Part 2 Korea

Chapter 6: South Korea's System

The Rise of Youth Organizations | The Northwest Youth Association | Labor Organized Through Unionism | The South Korean System

The ideology of | Educator Ahn Ho-sang | Korean liberalism and Syngman Rhee's hostile forces | Lee

Syngman Rhee's Leadership | Syngman Rhee and the Americans | The Problem of Cooperation with Japan

Chapter 7 Resistance to the South Korean Regime

1947: A Meaningless Year | A Struggle in the Villages | The Jeju Island Rebellion | The Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion

Chapter 8: Guerrilla Struggle

Guerrilla Forces in Jeolla Province | Guerrilla Forces in Gyeongsang Province | Guerrilla Methods Used | External Intervention and Suppression | Conclusion

Chapter 9 North Korea's System

Mass Parties | Cooperatives and Revolutionary Nationalism | Political Repression | Police and Intelligence

Chapter 10: The Soviet Union and North Korea

Koreans of Soviet descent | North Korean politics and economics and the Soviet Union | North Korea's perspective on the Soviet Union

Chapter 11 North Korea's Public Relations

The Withdrawal of Soviet Troops and the Influx of Chinese Influence, 1949–1950 | The Problem of Military Control | The Tough Impact of Mao Zedong's Victory: Is the East Red? | The Soviet Atomic Bomb | Conclusion

Note / Translator's Note / Index

preface

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Book ─ A Review of the Methods and Theories of American Foreign Policy

Science and Mystery: "The Problem of Highly Nonlinear and Unstable Liberal Borders" | Toward a Theory of American Foreign Policy | Incomprehensible Incrementalism and the American Egg | The State as the Purpose and Consequence of Class Struggle | Rulers and Interest Powers | International Cooperationism/Imperialism and Expansionism/Nationalism | Elements of American Foreign Policy: International Cooperationism, Containment, and Counterattack

Part 1: United States

Chapter 2: Blockade and International Cooperation

Politician Acheson | "The Great Crescent": The Acheson Line | Kennan's Engineering | The Politics of Strategy: The State Department and the War Department's Conflicts Over Korea | The Syngman Rhee Lobby in Washington: "I'm in Trouble Because of Syngman Rhee's Folly" | The UN as a Compromise | The Second US-Soviet Joint Commission | The UN and the 1948 Election

Chapter 3: Counterattack and Nationalism

Rethinking American Nationalism: The Politics and Economics of Isolationism/Counteroffensive | Expansionism and Minerals | Counteroffensives and Airpower | MacArthur and Willoughby: Local Counteroffensive Commands | The China Lobby, McCarthyism, and Counteroffensive | James Burnham: The Theorist of Interventionism

Chapter 4: Destiny to Enter the Predestined Labyrinth: Spies and Speculators

Central Intelligence Agency | Donovan's Cold War Stronghold | Unofficial Partners in East Asia: Chenault, Foley, Willow, Cook, and Other Key Figures | Goodfellow's Special Mission | Mole in the Maze: Britain's Spy | All the Gold: Gold, Tungsten, Black Sand, and Soybeans | Soybean Price Manipulation | Conclusion

Chapter 5: The Counterattack that Infiltrated the Bureaucracy

Containment and Counterattack: Relations with Japan | The Expanding Crescent | The Japanese Lobby and US Policy | Containment and Counterattack in National Security Council Document 68 | Conclusion

Part 2 Korea

Chapter 6: South Korea's System

The Rise of Youth Organizations | The Northwest Youth Association | Labor Organized Through Unionism | The South Korean System

The ideology of | Educator Ahn Ho-sang | Korean liberalism and Syngman Rhee's hostile forces | Lee

Syngman Rhee's Leadership | Syngman Rhee and the Americans | The Problem of Cooperation with Japan

Chapter 7 Resistance to the South Korean Regime

1947: A Meaningless Year | A Struggle in the Villages | The Jeju Island Rebellion | The Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion

Chapter 8: Guerrilla Struggle

Guerrilla Forces in Jeolla Province | Guerrilla Forces in Gyeongsang Province | Guerrilla Methods Used | External Intervention and Suppression | Conclusion

Chapter 9 North Korea's System

Mass Parties | Cooperatives and Revolutionary Nationalism | Political Repression | Police and Intelligence

Chapter 10: The Soviet Union and North Korea

Koreans of Soviet descent | North Korean politics and economics and the Soviet Union | North Korea's perspective on the Soviet Union

Chapter 11 North Korea's Public Relations

The Withdrawal of Soviet Troops and the Influx of Chinese Influence, 1949–1950 | The Problem of Military Control | The Tough Impact of Mao Zedong's Victory: Is the East Red? | The Soviet Atomic Bomb | Conclusion

Note / Translator's Note / Index

Into the book

I didn't originally plan on doing two volumes.

As I researched materials related to Korea from the late 1940s, I felt compelled to write two volumes, as 1947 was a watershed year in American policy.

The Cold War not only began in earnest with the announcement of the Truman Doctrine, but Dean Acheson also attempted to extend the doctrine to the defense of Korea.

I first saw this in a handwritten memo stapled to other material, written in January 1947, in which Secretary of State George Marshall instructed Acheson to establish a separate government in South Korea and link it to the Japanese economy.

This was part of a radically revised Japanese policy, which reversed the policy of rebuilding industries in Japan's neighboring countries and shifted the focus from stripping Japan of its military and political power to restoring it as an economic powerhouse (a policy that persists to this day).

In 1977, I was at the National Archives when an employee walked in with a large cart full of cardboard boxes and asked if I could read what was inside.

It was a 'captured document' from the '242nd Record Group', a report of publications and top secret materials collected by the US military when they occupied North Korea in the fall of 1950.

Suddenly, my research topic unfolded before me.

For example, while the Rodong Sinmun, published in the 1940s, had no copies available outside North Korea, this document contained almost all of its official organs.

After reading these materials for over two years, my understanding of North Korea has changed dramatically.

In Volume 1, I had primarily used previously classified American documents and materials published in South Korea in the late 1940s, but now I had access to material that no archivist had ever seen—because they couldn't read the language (there was some evidence that the CIA and other government agencies had intermittently deleted these documents over the years, but for the most part, it was like having material from 1951 in hand).

It is a sad fact that most American scholars who wrote about the Korean War cannot read Korean.

One of those people, William Stueck, even had the audacity to ask me if there was anything interesting in the 242 records.

I said there was nothing to interest you.

As time went on, my two beliefs deepened even more than when I wrote these books.

First, the decision by the US military government to re-employ virtually all Koreans who had collaborated with Japan, especially in the military and police, was of the utmost importance and priority.

Who could have imagined that Kim Seok-won, a Japanese colonel pursuing Korean anti-Japanese guerrillas in 1945, would become the commander of the 38th parallel throughout the summer of 1949? In contrast, nearly all of the North Korean leadership had been former anti-Japanese guerrillas.

Or think about this:

The two men, who were both Japanese military officers and good friends, graduated from the second class of the Korean Defense Guard Academy in 1946.

They are Park Chung-hee and Kim Jae-gyu.

This fundamental miscalculation, repeated later in the re-employment of officers who had collaborated with the French in Vietnam, shows that the United States, founded on the struggle against colonialism, had completely abandoned that orientation by the mid-20th century.

A second belief is that the People's Committee, which emerged in 1945, was crucial but has been almost entirely ignored in the literature on the Korean War.

As I studied the People's Committee for a long time and in more depth, and especially as I learned that the Jeju People's Committee had existed peacefully for three years but ended in a shameful bloodshed in which at least 10 percent of the island's population was horribly massacred, and that the massacre was led by Korean officers who had collaborated with the Americans and the Japanese, I began to think that, given these circumstances, one could soon understand that North Korea would find a way to secure its position by antagonizing those whom the majority of Koreans regarded as traitors.

A few years after completing Volume 2, Soviet documents related to the Korean War were declassified.

I was fairly quickly met with accusations that I had not grasped the content of this document.

Those documents showed that the Soviet Union was more heavily involved in Kim Il-sung's war than I had thought.

Although it was based on the 242nd record, I was wrong to overemphasize North Korea's independence.

Stalin was too much of a figure for North Korea to act independently without his approval.

I was right in my assertion that the Soviet Union did not want to enter this war.

According to the intelligence sources I have examined, Soviet submarines quickly withdrew from Korean waters after the outbreak of war, Korean People's Army military advisers withdrew or returned home, and Stalin did nothing to help them when North Korea was in its greatest crisis in the late 1950s.

I argued that China's participation in the war was partly to protect its industrial facilities in the northeast and to reward the tens of thousands of Koreans who had participated in the communist movement in China as early as the 1920s.

Although Chinese scholars have produced several excellent books on the Korean War, drawing on numerous new documents, I have found no reason to change my judgment on this matter.

I have even been accused of being a 'conspiracy theorist'.

Such people have many conspiracy theories, but, as with Donald Trump, there are few facts to substantiate them.

Since several conspiracies intersected in the documents during the last week of June 1950, readers, especially as they read Volume 2, will feel that there was a lot of conspiracy going on.

When I saw that prominent historians who had analyzed the same materials I had seen in the archives made no mention of them in their writings—say, the American coup plot to overthrow Chiang Kai-shek—I decided to follow a particular story, as long as it was supported, rather than let the evidence languish in various archives.

This method also did not go smoothly due to US authorities' refusal to declassify certain documents.

But I did my best to serve the inquiring readership that every writer desires.

I am deeply sorry for the high-ranking American leaders who recklessly and indiscriminately divided this historic nation after 1945 (then John J.

I would like to tell my Korean readers that I have always tried not to involve myself in the divisions that have been sparked by (there was no one more 'senior' than McIlroy).

According to numerous State Department documents produced during World War II, the United States entered Korea to prevent Koreans with guerrilla backgrounds from taking power, and now they say the successors of those guerrillas are sitting in Pyongyang with nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles (it's hard to think of a more failed policy, and the solution seems unlikely).

Because it was my homeland that divided Korea, I have always felt a sense of responsibility, which means that no matter what my personal views, I cannot take sides with either South or North Korea.

Regardless of the outcome, I believe, and have always believed, that a thorough historical inquiry is the best prescription and path toward the reconciliation that the two Koreas deserve.

The truth can set you free, and in this case the truth can be found in primary documents, where the actors of history often did the exact opposite of what they told the public.

People often ask me about my 'opinions' on the Korean War, and I try to answer kindly.

However, in these two books I have done my best to provide the basis for my judgment on the previously classified documents.

As someone once said, we all have the right to express our opinions, but we do not have the right to claim our opinions as facts.

I started Volume 1 by expressing my gratitude to the Koreans who taught me so much.

If I hadn't learned Korean and been able to read, I wouldn't have been able to understand their thoughts.

I am so happy that both books have now been faithfully translated into Korean and can be read in Korea.

As I researched materials related to Korea from the late 1940s, I felt compelled to write two volumes, as 1947 was a watershed year in American policy.

The Cold War not only began in earnest with the announcement of the Truman Doctrine, but Dean Acheson also attempted to extend the doctrine to the defense of Korea.

I first saw this in a handwritten memo stapled to other material, written in January 1947, in which Secretary of State George Marshall instructed Acheson to establish a separate government in South Korea and link it to the Japanese economy.

This was part of a radically revised Japanese policy, which reversed the policy of rebuilding industries in Japan's neighboring countries and shifted the focus from stripping Japan of its military and political power to restoring it as an economic powerhouse (a policy that persists to this day).

In 1977, I was at the National Archives when an employee walked in with a large cart full of cardboard boxes and asked if I could read what was inside.

It was a 'captured document' from the '242nd Record Group', a report of publications and top secret materials collected by the US military when they occupied North Korea in the fall of 1950.

Suddenly, my research topic unfolded before me.

For example, while the Rodong Sinmun, published in the 1940s, had no copies available outside North Korea, this document contained almost all of its official organs.

After reading these materials for over two years, my understanding of North Korea has changed dramatically.

In Volume 1, I had primarily used previously classified American documents and materials published in South Korea in the late 1940s, but now I had access to material that no archivist had ever seen—because they couldn't read the language (there was some evidence that the CIA and other government agencies had intermittently deleted these documents over the years, but for the most part, it was like having material from 1951 in hand).

It is a sad fact that most American scholars who wrote about the Korean War cannot read Korean.

One of those people, William Stueck, even had the audacity to ask me if there was anything interesting in the 242 records.

I said there was nothing to interest you.

As time went on, my two beliefs deepened even more than when I wrote these books.

First, the decision by the US military government to re-employ virtually all Koreans who had collaborated with Japan, especially in the military and police, was of the utmost importance and priority.

Who could have imagined that Kim Seok-won, a Japanese colonel pursuing Korean anti-Japanese guerrillas in 1945, would become the commander of the 38th parallel throughout the summer of 1949? In contrast, nearly all of the North Korean leadership had been former anti-Japanese guerrillas.

Or think about this:

The two men, who were both Japanese military officers and good friends, graduated from the second class of the Korean Defense Guard Academy in 1946.

They are Park Chung-hee and Kim Jae-gyu.

This fundamental miscalculation, repeated later in the re-employment of officers who had collaborated with the French in Vietnam, shows that the United States, founded on the struggle against colonialism, had completely abandoned that orientation by the mid-20th century.

A second belief is that the People's Committee, which emerged in 1945, was crucial but has been almost entirely ignored in the literature on the Korean War.

As I studied the People's Committee for a long time and in more depth, and especially as I learned that the Jeju People's Committee had existed peacefully for three years but ended in a shameful bloodshed in which at least 10 percent of the island's population was horribly massacred, and that the massacre was led by Korean officers who had collaborated with the Americans and the Japanese, I began to think that, given these circumstances, one could soon understand that North Korea would find a way to secure its position by antagonizing those whom the majority of Koreans regarded as traitors.

A few years after completing Volume 2, Soviet documents related to the Korean War were declassified.

I was fairly quickly met with accusations that I had not grasped the content of this document.

Those documents showed that the Soviet Union was more heavily involved in Kim Il-sung's war than I had thought.

Although it was based on the 242nd record, I was wrong to overemphasize North Korea's independence.

Stalin was too much of a figure for North Korea to act independently without his approval.

I was right in my assertion that the Soviet Union did not want to enter this war.

According to the intelligence sources I have examined, Soviet submarines quickly withdrew from Korean waters after the outbreak of war, Korean People's Army military advisers withdrew or returned home, and Stalin did nothing to help them when North Korea was in its greatest crisis in the late 1950s.

I argued that China's participation in the war was partly to protect its industrial facilities in the northeast and to reward the tens of thousands of Koreans who had participated in the communist movement in China as early as the 1920s.

Although Chinese scholars have produced several excellent books on the Korean War, drawing on numerous new documents, I have found no reason to change my judgment on this matter.

I have even been accused of being a 'conspiracy theorist'.

Such people have many conspiracy theories, but, as with Donald Trump, there are few facts to substantiate them.

Since several conspiracies intersected in the documents during the last week of June 1950, readers, especially as they read Volume 2, will feel that there was a lot of conspiracy going on.

When I saw that prominent historians who had analyzed the same materials I had seen in the archives made no mention of them in their writings—say, the American coup plot to overthrow Chiang Kai-shek—I decided to follow a particular story, as long as it was supported, rather than let the evidence languish in various archives.

This method also did not go smoothly due to US authorities' refusal to declassify certain documents.

But I did my best to serve the inquiring readership that every writer desires.

I am deeply sorry for the high-ranking American leaders who recklessly and indiscriminately divided this historic nation after 1945 (then John J.

I would like to tell my Korean readers that I have always tried not to involve myself in the divisions that have been sparked by (there was no one more 'senior' than McIlroy).

According to numerous State Department documents produced during World War II, the United States entered Korea to prevent Koreans with guerrilla backgrounds from taking power, and now they say the successors of those guerrillas are sitting in Pyongyang with nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles (it's hard to think of a more failed policy, and the solution seems unlikely).

Because it was my homeland that divided Korea, I have always felt a sense of responsibility, which means that no matter what my personal views, I cannot take sides with either South or North Korea.

Regardless of the outcome, I believe, and have always believed, that a thorough historical inquiry is the best prescription and path toward the reconciliation that the two Koreas deserve.

The truth can set you free, and in this case the truth can be found in primary documents, where the actors of history often did the exact opposite of what they told the public.

People often ask me about my 'opinions' on the Korean War, and I try to answer kindly.

However, in these two books I have done my best to provide the basis for my judgment on the previously classified documents.

As someone once said, we all have the right to express our opinions, but we do not have the right to claim our opinions as facts.

I started Volume 1 by expressing my gratitude to the Koreans who taught me so much.

If I hadn't learned Korean and been able to read, I wouldn't have been able to understand their thoughts.

I am so happy that both books have now been faithfully translated into Korean and can be read in Korea.

---From the "Korean Edition Preface"

Publisher's Review

Significance of the publication of the Korean edition

What does it mean to publish “The Origins of the Korean War” at this point in time?

As Professor Shin Bok-ryong said, the Korean War has a very complex and subtle nature.

It was a war without a declaration of war, a war without victory or defeat, the first war in which the United States failed to win, a war that failed to eliminate evil but instead solidified division, maximizing the tragedy of national history, a war that accelerated the ideological confrontation (Cold War), and above all, it was the war with the greatest controversy over responsibility for its outbreak.

This war is still ongoing, and North Korea, the opposing party, has now completed its nuclear armament. The Korean Peninsula remains wedged between major powers, and in a society where even minor provocations near the 38th parallel make headlines, this war can never become history.

It is still a pressing issue that strongly defines our reality.

In a land where the term "division system" still holds true, the Korean War needs to bring to the forefront the social dynamics of the long period of time obscured by the apparent combat patterns and the debate over responsibility for the outbreak of the war.

Bruce Cumings's The Origins of the Korean War is an outstanding achievement in this regard.

Cummings' book has been met with much praise and criticism.

It is no longer necessary to emphasize that among them, the 'revisionists' were the first to challenge the traditionalist theory that the war began with a large-scale invasion by North Korea under Soviet command.

Re-examining Cummings's Jack within the framework of discourses such as traditionalism, revisionism, and neo-revisionism is something that should be avoided at all costs, as it would overly simplify this three-dimensional book.

The very act of adding the word "caution" to the word "correction," which means that the facts are wrong and need to be corrected, is an unreasonable grammar in the first place. In addition, there have been so many positions that have been discarded because they were proven to be erroneous that it is correct to say that the discussion itself has lost its validity.

Professor Jeong Byeong-jun, author of “The Korean War,” criticized Cumings’s claim that “it is impossible to say that the war started in June 1950 was anyone’s fault,” but if you read Cumings’ book in its entirety, you can feel that Cumings is heavily inclined towards the theory of American responsibility for the war.

There was also much criticism for overemphasizing the internal elements of the Korean War and defining it as a “civil war,” but a careful reading of this complete translation reveals that Cumings’ emphasis on “civil war” was intended to raise questions about viewing the issue solely as a confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. He did not deny that the Korean War was an “international war with a civil nature,” but rather, he restored in detail the process that led to the war according to the United States’ global strategy.

Professor Park Myeong-rim, a strong critic of Cumings, pointed out that “Bruce Cumings is the one who has most strongly doubted the invasion theory and has tried to find a counterargument to it,” but Cumings had pointed out from the beginning that the invasion theory was absurd, and in a situation where small-scale guerrilla warfare and local warfare had been repeated for over a year since before 1950, resulting in over 100,000 casualties, he was skeptical as to whether North Korea’s transition to an all-out war could really be summarized as an invasion, and he only demanded a more accurate picture of the reality.

In 1952, he published “The Secret History of the Korean War” and claimed that Syngman Rhee, MacArthur, Dulles, and Chiang Kai-shek aided and abetted the war through a conspiracy of silence, even though they knew it would break out.

In addition to F. Stone's 'invasion inducement theory', this part is also being reexamined in Cummings' book.

Some have even labeled Cummings a "conspiracy theorist," but it is true that Dean Acheson, then a U.S. State Department official, later privately said, "Korea saved us." It is also well known that the Korean War played a significant role in increasing defense spending necessary for the U.S. pursuit of global hegemony after the end of World War II and in unifying a divided nation.

There were also criticisms from Professor Son Ho-cheol and others that the 'farmers' section was given too much importance in the process of analyzing Donghak within Korea, and the importance of the 'labor' and 'workers' sections was barely addressed.

Anyway, now 『The Origins of the Korean War』 has revealed its massive body.

In particular, the second volume, which was not translated and was only rumored, is twice as long as the first volume, and compared to the first volume, which covered 1945-1947, it covers the period from 1947 to the outbreak of the war. Unlike the first volume, it takes a very detailed and specific look at the US foreign policy, world policy, Korean Peninsula policy, Soviet policy, and Japanese policy before the situation on the Korean Peninsula, and really painstakingly depicts the international aspect of this war.

Now, Cummings's book is being reread in Korean society, and by doing so, we must fully recognize that it is a detailed portrait of the times, meticulously depicting the various turbulent changes this society experienced from the colonial era to the Korean War, the social conflicts that resulted from them, and their eruptions.

And about the entry of the US military government, which was the starting point of the division system, and the specific actions the US took on this land to block the spread of communist forces and establish an outer boundary to pursue political and economic hegemony, etc.; about the strategies and mistakes they devised to control and take advantage of the countries and peoples that were rapidly gaining independence from colonies; about the social control, appeasement, and oppression that were carried out based on them; about the fact that the atmosphere of socialist revolution in the unoccupied area after the colonial power withdrew was stronger than we imagined due to the severe class conflict that could only be resolved through revolution during the late Joseon Dynasty and the Japanese colonial period; and that North Korea's ambition to communize South Korea was therefore not such a terrible imagination in the context of the time. I hope there will be much discussion about these from a realist perspective that is free from camps, ideologies, and mannerisms.

In a public atmosphere that is still overly emotional about national realities and mired in a sense of victimization, Cumings's position, which recognizes aspects of colonial modernization such as railroad construction and industrialization facilities as unique characteristics of Korea compared to other Southeast Asian countries that were colonies of the West, may be uncomfortable. On the other hand, the fact that he repeatedly and strongly criticizes the point in this book that the US military government tolerated pro-Japanese forces and gave them a soft landing through administrative power, and emphasizes this as the core element of civil war, clearly has something to suggest to us.

Volume 2, The Rumble of the Waterfall, 1947–1950

Until early 1947, Korea and its internal conflicts dominated the course of events.

The Cold War in Korea began in 1945, and the immature containment policy began as tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union developed on the Korean Peninsula and the United States responded to social and political movements in Korea.

By mid-1946, the two countries were effectively intensifying and escalating their rivalry as they increasingly felt the need to deploy troops along the 38th parallel, which was solidifying into a border.

The movement to establish a separate South Korean state under the full control of the United States reached a major turning point the year after liberation, and American policy reached a point of no return.

The suppression of the Autumn Uprising revealed the formidable oppressive nature of the colonial government and breathed life into the Korean government's bureaucracy.

The left wing in South Korea, which had dominated the situation until then, lost power and shifted its center of activity to Pyongyang.

In mid-1947, Yeo Un-hyeong died and Pak Hon-yong became subordinate to Kim Il-sung.

In early 1947, the Truman Doctrine and Japan's industrial revival shifted the overall center of gravity, and for the next three years, external forces dominated the political landscape in Korea.

South Korea's blockade policy foreshadowed and received high-level approval from Acheson's decision not to include South Korea, as well as Greece and Turkey, in the perimeter.

But what was behind it was not Haji's concerns about communism, but the political and economic situation of the Great Crescent.

This was the result of a worldview emerging in East Asia that sought to transform the United States into a global hegemon, playing an increasingly unilateral role in a second-best world, while applying the Marshall Plan to Europe and, more broadly, continuing to employ the Rooseveltian rhetoric of international cooperation.

As Korea's importance to the United States grew, the Soviet Union withdrew its troops, and Kim Il-sung sent his troops to fight in China's civil war.

As the blockade policy gained support, a counter-strategy emerged, the laws of which originated in the declining political and economic conditions of the previous generation and favored individual entrepreneurs and domestic capitalists rather than multinational corporations.

They were generally expansionist, and their preferred strategy was counter-offensive.

Because “foreign policy” was entirely new to the superpower, the government agencies responsible for foreign policy had almost complete autonomy from society at large.

At the time, those interested in foreign policy were people of noble blood, graduated from prestigious universities in the eastern United States, and worked in the Bureau of Foreign Affairs of the State Department. In reality, they were implementing regional policies in the northeastern and southern United States.

New England traders, Southern planters, and Wall Street investors were the “special interests” behind foreign affairs.

But in the 1930s, a new hegemonic power emerged: the industrial exporters, and by the late 1940s, as new institutions proliferated to maintain that hegemony, an internal power struggle unfolded that had little to do with the average American.

Therefore, the events that became the prototypes of the First and Second Korean Wars were formed a year earlier, at a time when calls for a counterattack were boiling within the U.S. government and the last U.S. combat units had withdrawn from Korea.

There are two reasons why this counterattack was so widely agreed upon: first, the existence of a superordinate structure called “China,” whose communist revolution had enabled conservatives to avenge the 1948 elections and the New Deal; and second, the resurgent Japan, a crucial mechanism whose politics and economy had largely fallen under communist control in the region where it was located.

Liberal and conservative factions in American politics united in their support of Dean Acheson's June decision to intervene in the Korean War, but later agreed to advance northward for different reasons.

The former hoped to stop at the Yalu River, but the latter sought to advance into the unknown wilderness of China.

Their bond was broken when they actually clashed with China.

The counter-offensive strategy and the forces that previously supported it have moved away from reality and into a nostalgic oblivion that yearns for the past, and containment has become the default choice for the leadership leading foreign policy.

Meanwhile, as Koreans sought to regain control of the situation, a kind of law of motion emerged in Korea.

Syngman Rhee, with the support of the United States and the approval of the United Nations, strengthened his power by mobilizing a large number of young people on the streets, but the economy, which had not gone through a complete process, deteriorated.

Kim Il-sung created a powerful army with Soviet-made equipment and Chinese-style training and sent it back to the country a year before the war.

North Korea has put significant effort into rebuilding the heavy industries introduced during the colonial era in order to pursue a priority strategy of building a foundation for resisting foreign invasion by promoting (communist) import-substitution industrialization.

In 1949-1950, South Koreans demonstrated, at least with American support, that they knew how to fight guerrillas.

As harvests increased and relations with Japan were reestablished, the economy began to pick up.

However, the war that began on June 25th was a problem within the Korean Peninsula and the end of a conflict that dates back to the colonial era.

In other words, the war was fought by a few people centered around Kim Il-sung and a few people centered around Kim Seok-won.

But the war changed South Korea.

In a sense, it was the same revolution that was needed for Korea's social structure but had not been realized in the previous five years.

The revolution was a capitalist revolution.

The war shortened and accelerated the period of transformation by ending the landlord system and freeing the country from the obsession with compulsory management (which accounted for 80 percent of the national budget).

The wealthy landowner class has deeply infiltrated the country, hindering development and paralyzing the bureaucracy.

The National Assembly, controlled by landowners, kept the executive power in check from outside.

Figures with strong political convictions, such as Jo Byeong-ok and Jang Taek-sang, took control of the government's coercive apparatus together with their supporters.

The fact that best illustrates the declining power of the Korean landlord class, its indescribable stubborn backwardness, and the fundamental nature of the class struggle unfolding in Korea is that, even while the world's most powerful nation was waging a terrible war for them, they stubbornly resisted to regain their birthright: private property in both South and North Korea.

They believed that this was the purpose of the war and that they were right.

Land redistribution did not occur until the summer of 1950, when North Korea purged this class and separated the landlords from their land, leaving them at the disposal of the Americans.

If the Korean War was an all-out war for Koreans, it was an opportunity for Americans to establish and reorganize their country's hegemony.

From this perspective, as Acheson said, it was not a Korean war.

It was an incident that could have happened anywhere in the world.

Also in 1954, Acheson, reflecting on the past at a conference held to help write his memoirs and to undermine MacArthur's standing, casually remarked:

“Korea showed up and saved us.”

Acheson cited National Security Council Document 68, the most important Cold War document of modern times, and pointed out that Korea was a necessary crisis that made possible the massive defense spending called for in that document.

More broadly speaking, Korea was the crisis that made possible the second wave of nation-building promoted by the United States in the 20th century.

The New Deal was the first wave, the security state the second, and the associated bureaucracy grew rapidly from the early 1950s onward.

As a result, the Korean War became an opportunity to pursue hegemony externally and nation-building internally.

However, it is now a common view in research literature, at least in related academic literature, that Korea was a good opportunity to establish American hegemony.

It is generally argued that Korea triggered the globalization of the containment policy, expanding Kennan's limited containment into the unrestricted intervention of Nietzsche and Dulles.

However, this book discusses the construction and reorganization of hegemony, and discovers a new history through “reorganization.”

Furthermore, National Security Council Document 68 did not only address the globalization of blockades, but also the dialectic between blockades and counterattacks.

National Security Council Document 48 signaled the end of a thorough reevaluation of America's Asia policy, which had been underway to interpret the communist revolution in China and the beginnings of Japan's industrial revival.

There too we see the same dialectic between blockade and counterattack.

In late August, Truman and Acheson decided to advance north, and Washington gave MacArthur broad support for his advance.

The precarious compromise between blockade and counteroffensive that had persisted from 1947 to 1950, despite the lack of bipartisan cooperation in Asia and, above all, the lack of financial resources to support the new hegemony, came close to a compromise during the two-month northward advance from late August to late October 1950.

The counteroffensive policy faced its greatest postwar crisis as it was counterattacked by a reorganized Korean People's Army and 200,000 Chinese "People's Volunteer Army" soldiers, forcing Washington to halt the escalation of hostilities.

In the winter of 1950, centrists like Acheson and Nitze realized belatedly that they had to pursue a policy of containment.

What does it mean to publish “The Origins of the Korean War” at this point in time?

As Professor Shin Bok-ryong said, the Korean War has a very complex and subtle nature.

It was a war without a declaration of war, a war without victory or defeat, the first war in which the United States failed to win, a war that failed to eliminate evil but instead solidified division, maximizing the tragedy of national history, a war that accelerated the ideological confrontation (Cold War), and above all, it was the war with the greatest controversy over responsibility for its outbreak.

This war is still ongoing, and North Korea, the opposing party, has now completed its nuclear armament. The Korean Peninsula remains wedged between major powers, and in a society where even minor provocations near the 38th parallel make headlines, this war can never become history.

It is still a pressing issue that strongly defines our reality.

In a land where the term "division system" still holds true, the Korean War needs to bring to the forefront the social dynamics of the long period of time obscured by the apparent combat patterns and the debate over responsibility for the outbreak of the war.

Bruce Cumings's The Origins of the Korean War is an outstanding achievement in this regard.

Cummings' book has been met with much praise and criticism.

It is no longer necessary to emphasize that among them, the 'revisionists' were the first to challenge the traditionalist theory that the war began with a large-scale invasion by North Korea under Soviet command.

Re-examining Cummings's Jack within the framework of discourses such as traditionalism, revisionism, and neo-revisionism is something that should be avoided at all costs, as it would overly simplify this three-dimensional book.

The very act of adding the word "caution" to the word "correction," which means that the facts are wrong and need to be corrected, is an unreasonable grammar in the first place. In addition, there have been so many positions that have been discarded because they were proven to be erroneous that it is correct to say that the discussion itself has lost its validity.

Professor Jeong Byeong-jun, author of “The Korean War,” criticized Cumings’s claim that “it is impossible to say that the war started in June 1950 was anyone’s fault,” but if you read Cumings’ book in its entirety, you can feel that Cumings is heavily inclined towards the theory of American responsibility for the war.

There was also much criticism for overemphasizing the internal elements of the Korean War and defining it as a “civil war,” but a careful reading of this complete translation reveals that Cumings’ emphasis on “civil war” was intended to raise questions about viewing the issue solely as a confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. He did not deny that the Korean War was an “international war with a civil nature,” but rather, he restored in detail the process that led to the war according to the United States’ global strategy.

Professor Park Myeong-rim, a strong critic of Cumings, pointed out that “Bruce Cumings is the one who has most strongly doubted the invasion theory and has tried to find a counterargument to it,” but Cumings had pointed out from the beginning that the invasion theory was absurd, and in a situation where small-scale guerrilla warfare and local warfare had been repeated for over a year since before 1950, resulting in over 100,000 casualties, he was skeptical as to whether North Korea’s transition to an all-out war could really be summarized as an invasion, and he only demanded a more accurate picture of the reality.

In 1952, he published “The Secret History of the Korean War” and claimed that Syngman Rhee, MacArthur, Dulles, and Chiang Kai-shek aided and abetted the war through a conspiracy of silence, even though they knew it would break out.

In addition to F. Stone's 'invasion inducement theory', this part is also being reexamined in Cummings' book.

Some have even labeled Cummings a "conspiracy theorist," but it is true that Dean Acheson, then a U.S. State Department official, later privately said, "Korea saved us." It is also well known that the Korean War played a significant role in increasing defense spending necessary for the U.S. pursuit of global hegemony after the end of World War II and in unifying a divided nation.

There were also criticisms from Professor Son Ho-cheol and others that the 'farmers' section was given too much importance in the process of analyzing Donghak within Korea, and the importance of the 'labor' and 'workers' sections was barely addressed.

Anyway, now 『The Origins of the Korean War』 has revealed its massive body.

In particular, the second volume, which was not translated and was only rumored, is twice as long as the first volume, and compared to the first volume, which covered 1945-1947, it covers the period from 1947 to the outbreak of the war. Unlike the first volume, it takes a very detailed and specific look at the US foreign policy, world policy, Korean Peninsula policy, Soviet policy, and Japanese policy before the situation on the Korean Peninsula, and really painstakingly depicts the international aspect of this war.

Now, Cummings's book is being reread in Korean society, and by doing so, we must fully recognize that it is a detailed portrait of the times, meticulously depicting the various turbulent changes this society experienced from the colonial era to the Korean War, the social conflicts that resulted from them, and their eruptions.

And about the entry of the US military government, which was the starting point of the division system, and the specific actions the US took on this land to block the spread of communist forces and establish an outer boundary to pursue political and economic hegemony, etc.; about the strategies and mistakes they devised to control and take advantage of the countries and peoples that were rapidly gaining independence from colonies; about the social control, appeasement, and oppression that were carried out based on them; about the fact that the atmosphere of socialist revolution in the unoccupied area after the colonial power withdrew was stronger than we imagined due to the severe class conflict that could only be resolved through revolution during the late Joseon Dynasty and the Japanese colonial period; and that North Korea's ambition to communize South Korea was therefore not such a terrible imagination in the context of the time. I hope there will be much discussion about these from a realist perspective that is free from camps, ideologies, and mannerisms.

In a public atmosphere that is still overly emotional about national realities and mired in a sense of victimization, Cumings's position, which recognizes aspects of colonial modernization such as railroad construction and industrialization facilities as unique characteristics of Korea compared to other Southeast Asian countries that were colonies of the West, may be uncomfortable. On the other hand, the fact that he repeatedly and strongly criticizes the point in this book that the US military government tolerated pro-Japanese forces and gave them a soft landing through administrative power, and emphasizes this as the core element of civil war, clearly has something to suggest to us.

Volume 2, The Rumble of the Waterfall, 1947–1950

Until early 1947, Korea and its internal conflicts dominated the course of events.

The Cold War in Korea began in 1945, and the immature containment policy began as tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union developed on the Korean Peninsula and the United States responded to social and political movements in Korea.

By mid-1946, the two countries were effectively intensifying and escalating their rivalry as they increasingly felt the need to deploy troops along the 38th parallel, which was solidifying into a border.

The movement to establish a separate South Korean state under the full control of the United States reached a major turning point the year after liberation, and American policy reached a point of no return.

The suppression of the Autumn Uprising revealed the formidable oppressive nature of the colonial government and breathed life into the Korean government's bureaucracy.

The left wing in South Korea, which had dominated the situation until then, lost power and shifted its center of activity to Pyongyang.

In mid-1947, Yeo Un-hyeong died and Pak Hon-yong became subordinate to Kim Il-sung.

In early 1947, the Truman Doctrine and Japan's industrial revival shifted the overall center of gravity, and for the next three years, external forces dominated the political landscape in Korea.

South Korea's blockade policy foreshadowed and received high-level approval from Acheson's decision not to include South Korea, as well as Greece and Turkey, in the perimeter.

But what was behind it was not Haji's concerns about communism, but the political and economic situation of the Great Crescent.

This was the result of a worldview emerging in East Asia that sought to transform the United States into a global hegemon, playing an increasingly unilateral role in a second-best world, while applying the Marshall Plan to Europe and, more broadly, continuing to employ the Rooseveltian rhetoric of international cooperation.

As Korea's importance to the United States grew, the Soviet Union withdrew its troops, and Kim Il-sung sent his troops to fight in China's civil war.

As the blockade policy gained support, a counter-strategy emerged, the laws of which originated in the declining political and economic conditions of the previous generation and favored individual entrepreneurs and domestic capitalists rather than multinational corporations.

They were generally expansionist, and their preferred strategy was counter-offensive.

Because “foreign policy” was entirely new to the superpower, the government agencies responsible for foreign policy had almost complete autonomy from society at large.

At the time, those interested in foreign policy were people of noble blood, graduated from prestigious universities in the eastern United States, and worked in the Bureau of Foreign Affairs of the State Department. In reality, they were implementing regional policies in the northeastern and southern United States.

New England traders, Southern planters, and Wall Street investors were the “special interests” behind foreign affairs.

But in the 1930s, a new hegemonic power emerged: the industrial exporters, and by the late 1940s, as new institutions proliferated to maintain that hegemony, an internal power struggle unfolded that had little to do with the average American.

Therefore, the events that became the prototypes of the First and Second Korean Wars were formed a year earlier, at a time when calls for a counterattack were boiling within the U.S. government and the last U.S. combat units had withdrawn from Korea.

There are two reasons why this counterattack was so widely agreed upon: first, the existence of a superordinate structure called “China,” whose communist revolution had enabled conservatives to avenge the 1948 elections and the New Deal; and second, the resurgent Japan, a crucial mechanism whose politics and economy had largely fallen under communist control in the region where it was located.

Liberal and conservative factions in American politics united in their support of Dean Acheson's June decision to intervene in the Korean War, but later agreed to advance northward for different reasons.

The former hoped to stop at the Yalu River, but the latter sought to advance into the unknown wilderness of China.

Their bond was broken when they actually clashed with China.

The counter-offensive strategy and the forces that previously supported it have moved away from reality and into a nostalgic oblivion that yearns for the past, and containment has become the default choice for the leadership leading foreign policy.

Meanwhile, as Koreans sought to regain control of the situation, a kind of law of motion emerged in Korea.

Syngman Rhee, with the support of the United States and the approval of the United Nations, strengthened his power by mobilizing a large number of young people on the streets, but the economy, which had not gone through a complete process, deteriorated.

Kim Il-sung created a powerful army with Soviet-made equipment and Chinese-style training and sent it back to the country a year before the war.

North Korea has put significant effort into rebuilding the heavy industries introduced during the colonial era in order to pursue a priority strategy of building a foundation for resisting foreign invasion by promoting (communist) import-substitution industrialization.

In 1949-1950, South Koreans demonstrated, at least with American support, that they knew how to fight guerrillas.

As harvests increased and relations with Japan were reestablished, the economy began to pick up.

However, the war that began on June 25th was a problem within the Korean Peninsula and the end of a conflict that dates back to the colonial era.

In other words, the war was fought by a few people centered around Kim Il-sung and a few people centered around Kim Seok-won.

But the war changed South Korea.

In a sense, it was the same revolution that was needed for Korea's social structure but had not been realized in the previous five years.

The revolution was a capitalist revolution.

The war shortened and accelerated the period of transformation by ending the landlord system and freeing the country from the obsession with compulsory management (which accounted for 80 percent of the national budget).

The wealthy landowner class has deeply infiltrated the country, hindering development and paralyzing the bureaucracy.

The National Assembly, controlled by landowners, kept the executive power in check from outside.

Figures with strong political convictions, such as Jo Byeong-ok and Jang Taek-sang, took control of the government's coercive apparatus together with their supporters.

The fact that best illustrates the declining power of the Korean landlord class, its indescribable stubborn backwardness, and the fundamental nature of the class struggle unfolding in Korea is that, even while the world's most powerful nation was waging a terrible war for them, they stubbornly resisted to regain their birthright: private property in both South and North Korea.

They believed that this was the purpose of the war and that they were right.

Land redistribution did not occur until the summer of 1950, when North Korea purged this class and separated the landlords from their land, leaving them at the disposal of the Americans.

If the Korean War was an all-out war for Koreans, it was an opportunity for Americans to establish and reorganize their country's hegemony.

From this perspective, as Acheson said, it was not a Korean war.

It was an incident that could have happened anywhere in the world.

Also in 1954, Acheson, reflecting on the past at a conference held to help write his memoirs and to undermine MacArthur's standing, casually remarked:

“Korea showed up and saved us.”

Acheson cited National Security Council Document 68, the most important Cold War document of modern times, and pointed out that Korea was a necessary crisis that made possible the massive defense spending called for in that document.

More broadly speaking, Korea was the crisis that made possible the second wave of nation-building promoted by the United States in the 20th century.

The New Deal was the first wave, the security state the second, and the associated bureaucracy grew rapidly from the early 1950s onward.

As a result, the Korean War became an opportunity to pursue hegemony externally and nation-building internally.

However, it is now a common view in research literature, at least in related academic literature, that Korea was a good opportunity to establish American hegemony.

It is generally argued that Korea triggered the globalization of the containment policy, expanding Kennan's limited containment into the unrestricted intervention of Nietzsche and Dulles.

However, this book discusses the construction and reorganization of hegemony, and discovers a new history through “reorganization.”

Furthermore, National Security Council Document 68 did not only address the globalization of blockades, but also the dialectic between blockades and counterattacks.

National Security Council Document 48 signaled the end of a thorough reevaluation of America's Asia policy, which had been underway to interpret the communist revolution in China and the beginnings of Japan's industrial revival.

There too we see the same dialectic between blockade and counterattack.

In late August, Truman and Acheson decided to advance north, and Washington gave MacArthur broad support for his advance.

The precarious compromise between blockade and counteroffensive that had persisted from 1947 to 1950, despite the lack of bipartisan cooperation in Asia and, above all, the lack of financial resources to support the new hegemony, came close to a compromise during the two-month northward advance from late August to late October 1950.

The counteroffensive policy faced its greatest postwar crisis as it was counterattacked by a reorganized Korean People's Army and 200,000 Chinese "People's Volunteer Army" soldiers, forcing Washington to halt the escalation of hostilities.

In the winter of 1950, centrists like Acheson and Nitze realized belatedly that they had to pursue a policy of containment.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: May 29, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 624 pages | 996g | 158*224*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791169090964

- ISBN10: 1169090966

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)