Social History of Literature and Art 3

|

Description

Book Introduction

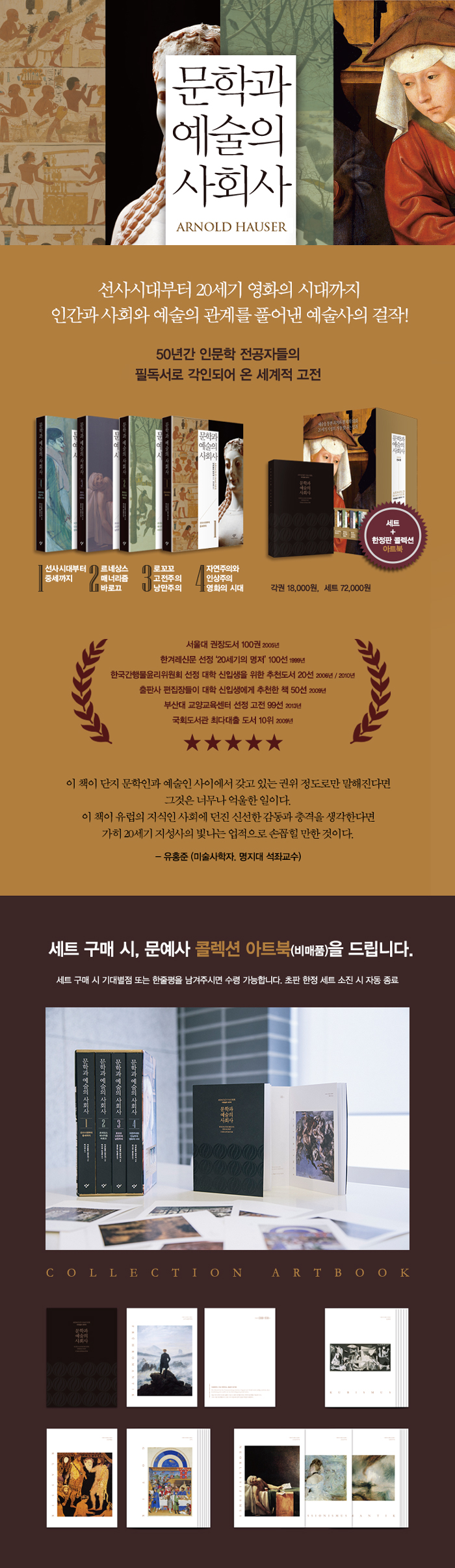

A classic of our time, beloved as a must-read for liberal arts students!

A steady seller that has been with Changbi readers for 50 years!

Now available in a new color edition with 500 points!

Arnold Hauser, a Hungarian-born intellectual who shone in the 20th century, dynamically explores the relationship between humans, society, and art, from prehistoric times to the present era of popular cinema.

This book, "The Social History of Literature and Art," pioneered the perspective of "sociology of art," which holds that art is a product of the times and social relations, and since its first English edition in 1951, it has been translated into over 20 languages and has become a must-read for intellectuals around the world as a "new history of art."

This year, 2016, marks the 50th anniversary of the first introduction of 『Social History of Literature and Art』 in Korea.

The last chapter of the book, "The Age of Cinema," was translated in the fall 1966 issue of the quarterly journal "Changjakgwa Bipyeong," and the modern section (equivalent to the current volume 4) was published in 1974 as the first volume of "Changbi New Books," causing a surprising stir in Korean intellectual circles.

This revised edition is the second revision following the 1999 revision.

This book is intended to meet the expectations of new readers, readers just beginning to explore art and society, as well as long-time readers who have developed a perspective on art and society through reading this book.

The text is designed to be easier and more fun to follow with a total of 500 color illustrations and a new design.

A steady seller that has been with Changbi readers for 50 years!

Now available in a new color edition with 500 points!

Arnold Hauser, a Hungarian-born intellectual who shone in the 20th century, dynamically explores the relationship between humans, society, and art, from prehistoric times to the present era of popular cinema.

This book, "The Social History of Literature and Art," pioneered the perspective of "sociology of art," which holds that art is a product of the times and social relations, and since its first English edition in 1951, it has been translated into over 20 languages and has become a must-read for intellectuals around the world as a "new history of art."

This year, 2016, marks the 50th anniversary of the first introduction of 『Social History of Literature and Art』 in Korea.

The last chapter of the book, "The Age of Cinema," was translated in the fall 1966 issue of the quarterly journal "Changjakgwa Bipyeong," and the modern section (equivalent to the current volume 4) was published in 1974 as the first volume of "Changbi New Books," causing a surprising stir in Korean intellectual circles.

This revised edition is the second revision following the 1999 revision.

This book is intended to meet the expectations of new readers, readers just beginning to explore art and society, as well as long-time readers who have developed a perspective on art and society through reading this book.

The text is designed to be easier and more fun to follow with a total of 500 color illustrations and a new design.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Chapter 1: Rococo and the Birth of a New Art | Chapter 2: Art in the Age of Enlightenment | Chapter 3: Romanticism

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

From the fringes of Europe to an icon of Korean intellectuals

Arnold Hauser (1892-1978), a Hungarian-Jewish writer whose first language was German, was a diaspora intellectual who spent most of his life abroad.

In his early twenties, while studying in Budapest, he worked briefly in the cultural institutions of the Hungarian revolutionary government, associating with György Lukács, Karl Mannheim, and Béla Walras.

Then, when the counter-revolution broke out, he left his home country and moved to Italy, then to Berlin, and then to Vienna to escape the Nazis.

His wife, who was studying art history with him, entered the University of Vienna, and her husband, Hauser, got a job at a film company to make a living.

In 1938, when Hitler took over Austria and he could no longer stay in Vienna, he went to London at the recommendation of his friend Mannheim.

And I started working on it after receiving a request to collect articles that could be grouped under the heading of ‘Sociology of Art.’

He worked at the film studio until 6 PM on weekdays, then split his time between late-night work and, on holidays, locked himself in the British Museum library, typing away at his typewriter, for 10 years.

Although the anthology of the sociology of art was ultimately left unfinished, its arduous journey culminated in the book, The Social History of Literature and Art, published in Hauser's own words.

Herbert Read, an art critic and publisher, noticed him sitting in the library and offered to publish his work.

Thus, the English edition (Social History of Art) was published in 1951, and, thanks to its success, the German edition (Sozialgeschichte der Kunst und Literatur) in Hauser's original language was published in Munich in 1953.

It was introduced to Korea in 1966, about 10 years later, through the fall issue of the quarterly magazine 『Creation and Criticism』, which was launched that year.

Professor Emeritus Baek Nak-cheong of Seoul National University, who created the magazine and co-translated the book, said, “It may not be considered a particularly rapid introduction, but given the circumstances at the time, it was certainly not slow” (Preface to the first revised edition).

The reaction was enthusiastic.

In a time when reading material was scarce, this book, steeped in Marxist historical materialism, barely managed to pass the threshold of censorship, and its overwhelming knowledge spanning from prehistoric times to the 20th century made it ideal for filling gaps in one's general knowledge.

It was an unusual yet natural event that the ‘Modern Times’ section of ‘Social History of Literature and Art’ was published as the first new book of Changbi in 1974.

At the time, the list of new books included major works by domestic intellectuals, such as Hwang Seok-yeong's "Guestland" (No. 3), Lee Young-hee's "Logic of the Transitional Era" (No. 4), and "The Complete Works of Shin Dong-yup" (No. 10). The fact that the translated book was placed at the very front of the list speaks volumes about the status this book held among Korean readers.

The book by an Eastern European leftist intellectual who distanced himself from the center of Western academia served as a must-read for 'practical intellectuals' and 'participatory intellectuals' in Korea, which experienced the April 19 Revolution, the May 16 Revolution, and military dictatorship.

In July 1977, when the poem "Slave Notebook" was embroiled in a case of blasphemy against a state institution, the defense attorney presented a passage from "The Social History of Literature and Art" as evidence to explain the relationship between literature and reality.

『Social History of Literature and Art』 was finally translated in its entirety in 1981, 15 years after its completion in the Modern Era Volume 2 (Changbi New Book No. 29), and after undergoing a single revision in 1999, it solidified its position as a required liberal arts textbook for university students.

From the 1960s to the 2000s, many who were struggling to establish their relationships with the world and themselves sought guidance from this book, and now it has become a 20th-century classic, boasting a history spanning half a century.

Three keywords for reading art and society

『The Social History of Art and Literature』 is often called a pioneering art history written from a Marxist perspective, or the beginning of the sociology of art.

Rather than relegating art to the realm of mystery, Hauser actively sought to explain it as a professional "job" and as part of economic activity that is socially produced and consumed.

At this time, three keywords can be selected that are useful for exploring the relationship between art and society.

The first is the art form.

From ancient cave paintings, heroic epics, aristocratic women's romances, medieval panel paintings, Shakespearean popular plays, public concerts for the bourgeoisie, Dutch chamber music, Enlightenment civic dramas, melodramas, and today's popular films, we can examine how the art forms we know emerged and how they differentiated and developed in the genres of literature, fine art, music, theater, and film.

It is also interesting to trace the process by which individual societies devise art forms optimized to their needs.

The second is the artist.

The image of the artist, which has changed with the times, such as the prehistoric magician, the medieval artisan, the Renaissance and Romantic genius, and the 19th-century bohemian, provides a basis for the author's insight that "the spiritual existence of the artist is always in danger regardless of East or West, past or present," and three-dimensionally illuminates the conflict of the artistic subject who has walked a tightrope between social demands and exceptional desires.

For example, the 17th-century Dutch civic culture allowed artists who were bound to the court greater freedom, but the moment an extraordinary painter like Rembrandt deviated from the classical tastes of the bourgeoisie, the market mercilessly rejected him.

Rembrandt's works, from The Night Watch to his late self-portraits, show his experimentation with seemingly abandoned attempts to satisfy a bourgeois clientele.

The third is the consumer or audience.

One of the main features of this book is that it raises the importance of consumers, who are often overshadowed by masterpieces (works of art) and geniuses (artists) in the history of art, to almost equal levels.

While commissioning, enjoying, and intervening in art production was once the exclusive domain of privileged classes such as the nobility and clergy, in the modern era, this practice gradually expanded to the middle class and, since the 20th century, to the general public.

Hauser, who witnessed the birth of a new public in real time through film, emphasizes that in order to move toward true "art democratization," we must broaden the public's perspective as much as possible, rather than restricting art to fit the current perspective of the majority.

The process by which Hauser explores the history of mankind over thousands and tens of thousands of years, going back and forth between art and society, is a complex and difficult “labyrinth” that cannot be simplified by saying that “art is a social product” (Süddeutsche Zeitung).

That is why it is still a “challenging” task (Lee Joo-heon, The Korea Times, April 25, 2007) that no one can even imagine.

A book that reminds us that classics still challenge us.

Social History of Literature and Art

Art historian Yoo Hong-jun, art critic Lee Ju-heon, music critic Lee Kang-sook, poet Hwang Ji-woo, novelist Seong Seok-je, sociologist Noh Myung-woo, physicist Jeong Jae-seung, film directors Lee Chang-dong and Kim Ji-woon… These are figures in the cultural and artistic world trusted by many Korean readers.

Although their areas of activity are different, they have one point of contact.

Everyone has read 『The Social History of Literature and Art』 at some point in their lives.

Yoo Hong-jun confessed, “It gave me a tremendous impression and shock, and it became the North Star of my lifelong study of art history” (Hankyoreh, November 28, 2013), and Noh Myung-woo said, “It is a book that presents an example of sociological questions about art or sociological questions about art” (Hankyoreh, May 14, 2014).

Lee Chang-dong also selected it as one of the 50 ‘books of life’ (Herald Economy, September 18, 2015).

The value of classics is bestowed upon the next generation.

There are books that are widely read in any era, but that doesn't mean they will remain so in future generations.

If a book is to still be read, it must have something to stimulate a new generation.

"The Social History of Literature and Art" is a book that shows how broad and deep human intellectual ambition can be.

In a time when there were no devices to store information or databases to search, the vast knowledge accumulated by one person over a decade by searching through documents and taking notes, along with the insight gained by systematizing and giving meaning to that knowledge through a consistent perspective, still serves as our "North Star" for coordinates.

Arnold Hauser (1892-1978), a Hungarian-Jewish writer whose first language was German, was a diaspora intellectual who spent most of his life abroad.

In his early twenties, while studying in Budapest, he worked briefly in the cultural institutions of the Hungarian revolutionary government, associating with György Lukács, Karl Mannheim, and Béla Walras.

Then, when the counter-revolution broke out, he left his home country and moved to Italy, then to Berlin, and then to Vienna to escape the Nazis.

His wife, who was studying art history with him, entered the University of Vienna, and her husband, Hauser, got a job at a film company to make a living.

In 1938, when Hitler took over Austria and he could no longer stay in Vienna, he went to London at the recommendation of his friend Mannheim.

And I started working on it after receiving a request to collect articles that could be grouped under the heading of ‘Sociology of Art.’

He worked at the film studio until 6 PM on weekdays, then split his time between late-night work and, on holidays, locked himself in the British Museum library, typing away at his typewriter, for 10 years.

Although the anthology of the sociology of art was ultimately left unfinished, its arduous journey culminated in the book, The Social History of Literature and Art, published in Hauser's own words.

Herbert Read, an art critic and publisher, noticed him sitting in the library and offered to publish his work.

Thus, the English edition (Social History of Art) was published in 1951, and, thanks to its success, the German edition (Sozialgeschichte der Kunst und Literatur) in Hauser's original language was published in Munich in 1953.

It was introduced to Korea in 1966, about 10 years later, through the fall issue of the quarterly magazine 『Creation and Criticism』, which was launched that year.

Professor Emeritus Baek Nak-cheong of Seoul National University, who created the magazine and co-translated the book, said, “It may not be considered a particularly rapid introduction, but given the circumstances at the time, it was certainly not slow” (Preface to the first revised edition).

The reaction was enthusiastic.

In a time when reading material was scarce, this book, steeped in Marxist historical materialism, barely managed to pass the threshold of censorship, and its overwhelming knowledge spanning from prehistoric times to the 20th century made it ideal for filling gaps in one's general knowledge.

It was an unusual yet natural event that the ‘Modern Times’ section of ‘Social History of Literature and Art’ was published as the first new book of Changbi in 1974.

At the time, the list of new books included major works by domestic intellectuals, such as Hwang Seok-yeong's "Guestland" (No. 3), Lee Young-hee's "Logic of the Transitional Era" (No. 4), and "The Complete Works of Shin Dong-yup" (No. 10). The fact that the translated book was placed at the very front of the list speaks volumes about the status this book held among Korean readers.

The book by an Eastern European leftist intellectual who distanced himself from the center of Western academia served as a must-read for 'practical intellectuals' and 'participatory intellectuals' in Korea, which experienced the April 19 Revolution, the May 16 Revolution, and military dictatorship.

In July 1977, when the poem "Slave Notebook" was embroiled in a case of blasphemy against a state institution, the defense attorney presented a passage from "The Social History of Literature and Art" as evidence to explain the relationship between literature and reality.

『Social History of Literature and Art』 was finally translated in its entirety in 1981, 15 years after its completion in the Modern Era Volume 2 (Changbi New Book No. 29), and after undergoing a single revision in 1999, it solidified its position as a required liberal arts textbook for university students.

From the 1960s to the 2000s, many who were struggling to establish their relationships with the world and themselves sought guidance from this book, and now it has become a 20th-century classic, boasting a history spanning half a century.

Three keywords for reading art and society

『The Social History of Art and Literature』 is often called a pioneering art history written from a Marxist perspective, or the beginning of the sociology of art.

Rather than relegating art to the realm of mystery, Hauser actively sought to explain it as a professional "job" and as part of economic activity that is socially produced and consumed.

At this time, three keywords can be selected that are useful for exploring the relationship between art and society.

The first is the art form.

From ancient cave paintings, heroic epics, aristocratic women's romances, medieval panel paintings, Shakespearean popular plays, public concerts for the bourgeoisie, Dutch chamber music, Enlightenment civic dramas, melodramas, and today's popular films, we can examine how the art forms we know emerged and how they differentiated and developed in the genres of literature, fine art, music, theater, and film.

It is also interesting to trace the process by which individual societies devise art forms optimized to their needs.

The second is the artist.

The image of the artist, which has changed with the times, such as the prehistoric magician, the medieval artisan, the Renaissance and Romantic genius, and the 19th-century bohemian, provides a basis for the author's insight that "the spiritual existence of the artist is always in danger regardless of East or West, past or present," and three-dimensionally illuminates the conflict of the artistic subject who has walked a tightrope between social demands and exceptional desires.

For example, the 17th-century Dutch civic culture allowed artists who were bound to the court greater freedom, but the moment an extraordinary painter like Rembrandt deviated from the classical tastes of the bourgeoisie, the market mercilessly rejected him.

Rembrandt's works, from The Night Watch to his late self-portraits, show his experimentation with seemingly abandoned attempts to satisfy a bourgeois clientele.

The third is the consumer or audience.

One of the main features of this book is that it raises the importance of consumers, who are often overshadowed by masterpieces (works of art) and geniuses (artists) in the history of art, to almost equal levels.

While commissioning, enjoying, and intervening in art production was once the exclusive domain of privileged classes such as the nobility and clergy, in the modern era, this practice gradually expanded to the middle class and, since the 20th century, to the general public.

Hauser, who witnessed the birth of a new public in real time through film, emphasizes that in order to move toward true "art democratization," we must broaden the public's perspective as much as possible, rather than restricting art to fit the current perspective of the majority.

The process by which Hauser explores the history of mankind over thousands and tens of thousands of years, going back and forth between art and society, is a complex and difficult “labyrinth” that cannot be simplified by saying that “art is a social product” (Süddeutsche Zeitung).

That is why it is still a “challenging” task (Lee Joo-heon, The Korea Times, April 25, 2007) that no one can even imagine.

A book that reminds us that classics still challenge us.

Social History of Literature and Art

Art historian Yoo Hong-jun, art critic Lee Ju-heon, music critic Lee Kang-sook, poet Hwang Ji-woo, novelist Seong Seok-je, sociologist Noh Myung-woo, physicist Jeong Jae-seung, film directors Lee Chang-dong and Kim Ji-woon… These are figures in the cultural and artistic world trusted by many Korean readers.

Although their areas of activity are different, they have one point of contact.

Everyone has read 『The Social History of Literature and Art』 at some point in their lives.

Yoo Hong-jun confessed, “It gave me a tremendous impression and shock, and it became the North Star of my lifelong study of art history” (Hankyoreh, November 28, 2013), and Noh Myung-woo said, “It is a book that presents an example of sociological questions about art or sociological questions about art” (Hankyoreh, May 14, 2014).

Lee Chang-dong also selected it as one of the 50 ‘books of life’ (Herald Economy, September 18, 2015).

The value of classics is bestowed upon the next generation.

There are books that are widely read in any era, but that doesn't mean they will remain so in future generations.

If a book is to still be read, it must have something to stimulate a new generation.

"The Social History of Literature and Art" is a book that shows how broad and deep human intellectual ambition can be.

In a time when there were no devices to store information or databases to search, the vast knowledge accumulated by one person over a decade by searching through documents and taking notes, along with the insight gained by systematizing and giving meaning to that knowledge through a consistent perspective, still serves as our "North Star" for coordinates.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: February 15, 2016

- Page count, weight, size: 392 pages | 668g | 153*224*21mm

- ISBN13: 9788936483456

- ISBN10: 8936483455

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)