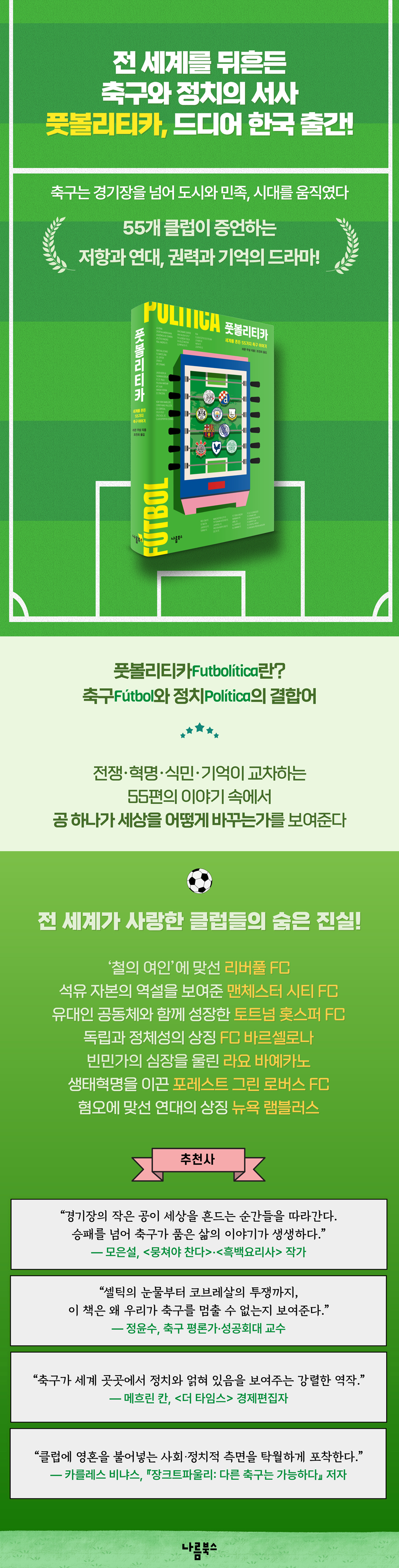

Footballitica

|

Description

Book Introduction

A fresh look at the world's political history and social movements through soccer.

Author Ramón Uzal, a Catalan historian, traces how football, since the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, has become more than just a sport, but a platform for political and social practice, using the case studies of 55 clubs. The author meticulously examines the history of football, examining issues of power, ethnicity, gender, religion, and class across different eras and regions, from why FC Barcelona became a symbol of the Catalan independence movement to how Liverpool fans were a driving force of political resistance against the Thatcher government and how women's football became a frontline for the gender equality movement.

The history of conflict and solidarity that unfolded on the soccer field, as depicted in this book, is itself a political history of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The author directly refutes the old notion that “football should be separated from politics,” and argues that football is a mirror that reveals the human condition as a “total social fact.”

Politics has always been at work in the World Cup, the league system, the national team's colors and emblems, and the collective passion of fans.

From African teams that dreamed of liberation from colonialism, to Palestinian national teams that started in refugee camps, to clubs that represented the working class's cities, to environmentalist clubs that fought against capital's sportswashing, the football field has always been a site of resistance and power.

Through the history of 'political football', we see how sports have illuminated and changed the world.

As a record proving that the soul of football lies not only on the field, but also in all the cracks and aspirations of society, this book will open new perspectives not only for football-loving readers, but also for those exploring the intersections of modern history, politics, and culture.

Author Ramón Uzal, a Catalan historian, traces how football, since the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, has become more than just a sport, but a platform for political and social practice, using the case studies of 55 clubs. The author meticulously examines the history of football, examining issues of power, ethnicity, gender, religion, and class across different eras and regions, from why FC Barcelona became a symbol of the Catalan independence movement to how Liverpool fans were a driving force of political resistance against the Thatcher government and how women's football became a frontline for the gender equality movement.

The history of conflict and solidarity that unfolded on the soccer field, as depicted in this book, is itself a political history of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The author directly refutes the old notion that “football should be separated from politics,” and argues that football is a mirror that reveals the human condition as a “total social fact.”

Politics has always been at work in the World Cup, the league system, the national team's colors and emblems, and the collective passion of fans.

From African teams that dreamed of liberation from colonialism, to Palestinian national teams that started in refugee camps, to clubs that represented the working class's cities, to environmentalist clubs that fought against capital's sportswashing, the football field has always been a site of resistance and power.

Through the history of 'political football', we see how sports have illuminated and changed the world.

As a record proving that the soul of football lies not only on the field, but also in all the cracks and aspirations of society, this book will open new perspectives not only for football-loving readers, but also for those exploring the intersections of modern history, politics, and culture.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

To the readers

introduction

Chapter 1 Britain and Ireland

Manchester City FC: The Humanitarian Origins of the Petrodollar Club

Tottenham Hotspur FC: Spurs' Jewish Traces

Liverpool FC: Fans Stand Up to the Iron Lady

Forest Green Rovers FC: Football to Save the Planet

British Ladies FC: The Feminist Roots of Women's Football

Celtic FC: A symbol of Irish republicanism in Scotland

Star of the Sea Youth Club: A Club Embracing Northern Ireland Tragedy

Chapter 2 France and Italy

Red Star FC: The red star that lights up the skies on the outskirts of Paris

SC Bastia: The Corsican Rebels

Juventus FC: A puppet of the Italian powers that be

Torino FC: When workers overthrow power

AS Roma: The Eternal City, the Heart of the People

Inter Milan: Name removed for being 'un-Italian'

Chapter 3: The Iberian Peninsula

Asociação Académica de Coimbra: Student Team Against Dictatorship

Atlético Madrid: The Club with a Thousand Faces

Real Madrid CF: A 'Royal' Club Led by Communists

Rayo Vallecano: The heart of Vallecas, the working-class team

FC Barcelona: The People's Army

CE Jupiter: With the stars as flags

The Spanish Girls Club: A Dream Shattered by World War I

Chapter 4 Central Europe and Scandinavia

Berliner FC Dúnamo: The Stasi's Club

FC Union Berlin: A team that stood up to the Stasi and capital

SC Tasmania von 1900 Berlin eV: A Product of the Cold War

FC St. Pauli: Three Rebellions

Warsaw, Poland: Lessons from Polish History

AFC Ajax: A Jewish club named after a Greek hero

Hakoah Bin: The Jewish Power That Moved Vienna

Christiania SC: A team that blooms and plays together

Chapter 5: The Balkan Peninsula

GNK Dinamo Zagreb: A Mirror of Modern Croatia

HNK Hajduk Split: The Indomitable Dalmatians

FK Sloboda Tuzla: Workers' City, Workers' Team

FK Velez Mostar: The Red Star of Mostar

Olympiacos CFP: Red Rebels of Piraeus

Chapter 6 Eastern Europe and the Caucasus

FC Olt Skornicești: The Dictator's Club, Its Rise and Fall

FC Dynamo Kyiv: Dynamo becomes the Ukrainian national team

FC Shakhtar Donetsk: A symbol of Donetsk history

FC Karpaty Lviv: A Citadel of Ukrainian Nationalism

FC Stroitel Pripyat: The Tragedy of Chernobyl

FC Lokomotiv Moscow: October Revolution Club

FC Akhmat Grozny: A Chechen Club in the Kremlin's Arms

Karabakh FK: A club in exile that left a ghost town behind

Chapter 7: The Middle East and Central Asia

Arbil SC: Iraqi Kurdistan's flagship team

Al Wehdat SC: A Palestinian Dream Continued Through Football

Shaheen Asmayye FC: Kabul's Falcons Soaring in a Land of Conflict

Chapter 8 Africa

Racing Universitaire Algiers: Camus and the Club in Colonial Algeria

Club Atlético de Tetouan: From colonial team to Moroccan powerhouse

JS Masirah: The club that justified the occupation of Western Sahara

HAFIA FC: Weapons of African Revolution

Passive Registers SC: Club of Peaceful Resistance

Chapter 9 America

New York Ramblers: Rainbow Football Against Homophobia

SC Corinthians Paulista: Democracy Blooms on the Football Field

CD Cobresal: Miners' Club of the Atacama Desert

Colo-Colo: Pinochet's Long Shadow

Mushuk Luna SC: Quechua Dream

CD Euzkadi: Basque national team stopped just short of winning the title

References

emblem

introduction

Chapter 1 Britain and Ireland

Manchester City FC: The Humanitarian Origins of the Petrodollar Club

Tottenham Hotspur FC: Spurs' Jewish Traces

Liverpool FC: Fans Stand Up to the Iron Lady

Forest Green Rovers FC: Football to Save the Planet

British Ladies FC: The Feminist Roots of Women's Football

Celtic FC: A symbol of Irish republicanism in Scotland

Star of the Sea Youth Club: A Club Embracing Northern Ireland Tragedy

Chapter 2 France and Italy

Red Star FC: The red star that lights up the skies on the outskirts of Paris

SC Bastia: The Corsican Rebels

Juventus FC: A puppet of the Italian powers that be

Torino FC: When workers overthrow power

AS Roma: The Eternal City, the Heart of the People

Inter Milan: Name removed for being 'un-Italian'

Chapter 3: The Iberian Peninsula

Asociação Académica de Coimbra: Student Team Against Dictatorship

Atlético Madrid: The Club with a Thousand Faces

Real Madrid CF: A 'Royal' Club Led by Communists

Rayo Vallecano: The heart of Vallecas, the working-class team

FC Barcelona: The People's Army

CE Jupiter: With the stars as flags

The Spanish Girls Club: A Dream Shattered by World War I

Chapter 4 Central Europe and Scandinavia

Berliner FC Dúnamo: The Stasi's Club

FC Union Berlin: A team that stood up to the Stasi and capital

SC Tasmania von 1900 Berlin eV: A Product of the Cold War

FC St. Pauli: Three Rebellions

Warsaw, Poland: Lessons from Polish History

AFC Ajax: A Jewish club named after a Greek hero

Hakoah Bin: The Jewish Power That Moved Vienna

Christiania SC: A team that blooms and plays together

Chapter 5: The Balkan Peninsula

GNK Dinamo Zagreb: A Mirror of Modern Croatia

HNK Hajduk Split: The Indomitable Dalmatians

FK Sloboda Tuzla: Workers' City, Workers' Team

FK Velez Mostar: The Red Star of Mostar

Olympiacos CFP: Red Rebels of Piraeus

Chapter 6 Eastern Europe and the Caucasus

FC Olt Skornicești: The Dictator's Club, Its Rise and Fall

FC Dynamo Kyiv: Dynamo becomes the Ukrainian national team

FC Shakhtar Donetsk: A symbol of Donetsk history

FC Karpaty Lviv: A Citadel of Ukrainian Nationalism

FC Stroitel Pripyat: The Tragedy of Chernobyl

FC Lokomotiv Moscow: October Revolution Club

FC Akhmat Grozny: A Chechen Club in the Kremlin's Arms

Karabakh FK: A club in exile that left a ghost town behind

Chapter 7: The Middle East and Central Asia

Arbil SC: Iraqi Kurdistan's flagship team

Al Wehdat SC: A Palestinian Dream Continued Through Football

Shaheen Asmayye FC: Kabul's Falcons Soaring in a Land of Conflict

Chapter 8 Africa

Racing Universitaire Algiers: Camus and the Club in Colonial Algeria

Club Atlético de Tetouan: From colonial team to Moroccan powerhouse

JS Masirah: The club that justified the occupation of Western Sahara

HAFIA FC: Weapons of African Revolution

Passive Registers SC: Club of Peaceful Resistance

Chapter 9 America

New York Ramblers: Rainbow Football Against Homophobia

SC Corinthians Paulista: Democracy Blooms on the Football Field

CD Cobresal: Miners' Club of the Atacama Desert

Colo-Colo: Pinochet's Long Shadow

Mushuk Luna SC: Quechua Dream

CD Euzkadi: Basque national team stopped just short of winning the title

References

emblem

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

Dissecting the global arena of power, resistance, and identity.

Proving that the history of football is the history of human freedom and solidarity

The most intelligent and passionate world history

"Futbolitika" is a world historical work exploring the intertwining of football and politics, written by Catalan Spanish historian Ramón Uzal.

The author refutes the common belief that “soccer has nothing to do with politics,” and offers a new perspective on world history through the history of soccer.

The title of the book, Futbolitica, is a portmanteau of the words ‘football’ (futbol) and ‘politics’ (politica), revealing that football is more than just a game; it is a social and political phenomenon.

Since the birth of modern football in industrialised Britain in the 19th century, clubs have symbolised the identity of cities and communities, sometimes as a resistance to dictatorship, and sometimes as a tool of power.

Through the case studies of 55 clubs around the world, including England, France, Spain, the Balkans, the Middle East, Africa, and South America, Usal traces how football has functioned as a 'total social fact'.

This is not a general list of sports history, but rather a task of reading the structure of modern and contemporary political history through soccer.

By analyzing the social context in which the club was born, the history of oppression and liberation, and the politics of solidarity created by fan culture, the author demonstrates that the stadium is a microcosm of society.

This book intersects two currents in particular: 'how football was used by power' and 'how football resisted power'.

Dissecting the history of oppression and resistance, class and identity, gender and colonization, capital and solidarity surrounding football, it reconstructs the history of football as a microscopic record of world politics, including the political confrontation between Barcelona and Real Madrid, the incident where Liverpool fans became a symbol of resistance against the Thatcher government, the case of football becoming a place for independence movements in colonial Africa, and even the modern phenomenon of 'sportswashing' where capital and image politics combine.

This book, which crosses the history of football, politics, and culture, allows us to understand the author's argument that football always illuminates the deepest rifts in society.

The stadium became the only space of freedom against imperialism and dictatorship.

Power may have the ball, but the game has always belonged to the people.

Among the nine chapters in this book, categorized by region, the most prominent of the football clubs are the people's teams that resisted imperialism and dictatorship.

Football has often been used as a means to legitimize dictatorships, but it is remembered more as a language of resistance than as a language of power.

Spain's Franco tried to use Real Madrid, Portugal's dictator Salazar tried to overcome international isolation with SL Benfica, Italy's fascist Mussolini (Juventus FC), Romania's Ceaușescu (Steaua Bucharest), and Chile's Pinochet (Colo-Colo) also used football clubs as propaganda tools, but the people have always found freedom in the stadium and made football their own history.

In 1939, when the Spanish Civil War ended and Franco came to power, the Catalan language and culture were banned.

And Barcelona has been identified as a 'stronghold of separatism'.

Franco tried to integrate FC Barcelona into his system, but the club took the opposite path.

At the home stadium, Camp Nou, Catalan flags waved secretly instead of Spanish ones, and the crowd sang in the suppressed language of Catalan.

It was not a stadium, but the last refuge of an oppressed language.

While Real Madrid was used as a 'sports diplomacy tool' by the Franco regime, Barcelona became a symbol of civil resistance.

Even today, decades after Franco's death, Barcelona is still called “Catalonia on the pitch.”

Portugal's right-wing government, Estado Novo, faced massive resistance at football stadiums.

The Académie de Coimbra, a university student association founded in the central city of Coimbra, staged a violent protest during the 1969 Portuguese Cup final.

Despite the football federation banning the Coimbra team's black armbands and the government deploying a large police force around the stadium, the final was filled with anti-dictatorship flags and banners, and the stadium was filled with spectators chanting along with the protesting students, protecting them.

Another famous scene in 1990 in Zagreb, Croatia, was when the Dinamo Zagreb captain kneed a Serbian policeman who was assaulting a Croatian fan.

This day marked the beginning of the violent struggle for Croatia's freedom and independence.

Teams from displaced minorities and colonies have made football stadiums their territory.

During the colonial era, Racing Universitaire Algiers, where French and Algerian players played together in Algeria, was ostensibly a 'team of unity'.

However, in the French mainland league, they were treated as 'second-class citizens'.

The young man who grew up in this contradiction was Albert Camus, a philosopher and goalkeeper.

Camus recalled, “I learned morality and humanity on the soccer field.”

There is also the Al-Wehdat SC, which is made up entirely of Palestinian refugees.

The team was founded in a refugee camp in Amman, Jordan.

The Jordanian government was wary of the team's nationalism, but fans waved Palestinian flags at every game.

Their cries were not mere cheers, but a declaration of existence.

Football of the era born under the factory chimney,

Sustainable football against modern capitalism

Football has also served as a political language of solidarity and liberation against oppression, inequality, and discrimination.

『Footbolitika』 analyzes that Liverpool FC was a space for workers' solidarity in Liverpool, England in the 1980s, the heart of neoliberalism.

When the Thatcher government's neoliberal reforms drove workers in industrial cities into layoffs and poverty, the football stadium was their only community space, and the red uniforms were their pride and a symbol of survival.

This has made opposition to the Conservative government a core part of fan identity.

Fans chanted anti-Thatcher slogans in solidarity with various social movements in Liverpool.

In Turin, Italy, where Juventus FC, a club founded by Fiat Capital, is holding on, there is also Torino FC, a team created by factory workers.

The conflict between labor and capital within a city was symbolized by soccer. The stands in Turin were filled with fans in overalls, and the stadium's chants resembled labor union slogans.

The fascist regime even changed the team's name to 'Torino Fiat' in 1944, but the attempt to maintain dictatorship through football ended in failure.

Juventus FC has the upper hand in terms of sporting achievements, but Torino FC remains the most beloved team in the Piedmontese capital.

This is because the historical memory of the club once enabling workers to defeat their employers still lingers strongly.

Rayo Vallecano, founded in 1924 in Vallecas, a working-class area on the outskirts of Madrid, Spain, is also presented as a symbolic model of a working-class community fighting against the football of power and capital.

Because the area's population is largely comprised of low-income workers and immigrants, the club has harbored a spirit of resistance from the beginning.

In a commercialised environment where the Spanish top division is named after banks, the club maintains a sense of community and class consciousness, even recently helping elderly people forced out by bank debt.

They were the only band to join the general strike against the government's labour market 'reforms' in 2010, and their fan club also actively participated in the general strike protests against the EU-led austerity measures in 2012.

Although small in size, Rayo Vallecano is a club that has retained a dignity that many of its rivals have lost, a working-class team proud of its roots.

The question posed by a British vegan club about 'what does football consume?' is also interesting.

The case of Forest Green Rovers, which rejected the logic of capital and created a new football culture centered on the environment and life, shows that football can become a platform for social movements.

In an era when oil capital dominated the league and fans cheered with disposable plastic cups, Forest Green Rovers, a small league club, promoted itself as a 'sustainable club'.

All meals were vegan, the stadium switched to solar power, and the grass was managed organically.

The book praised Forest Green Rovers as an iconic example of how football can contribute to the global fight against the climate crisis.

How soccer learns equality

Stadium owners who have won the 'right to participate'

In the summer of 2023, the Spanish women's national team won the World Cup for the first time.

But there was one scene on the podium that caused a bigger stir than the trophy.

Spanish Football Federation president Luis Rubiales kissed star player Genifer Hermoso without his consent.

Spanish society was instantly in an uproar.

“We won, but we are not yet equal.” After the incident, Rubiales resigned and the federation pledged to bring about substantial equality between the men’s and women’s teams.

The author sees this incident as showing that football is inherently a political phenomenon.

While women's football has enjoyed a surge in public attention and acclaim since 2017, female players remain far from being treated equally, and the high media attention paid to the women's league demonstrates that the fight for women's empowerment and gender equality is being waged through football.

British Ladies FC, introduced in this book as the world's first women's soccer team, was formed in England in 1895 and sent a message to a male-dominated society that women could also play on the field.

The founding goal was to go beyond soccer and advocate for women's social equality and suffrage.

The press ridiculed them and accused them of 'losing their feminine dignity', but their London debut drew a crowd of 10,000, and the women challenged dress codes by performing without corsets.

Despite social criticism, the team played over 100 exhibition games throughout the year, paving the way for women's liberation.

British Ladies FC is considered the first sports political act to demand physical freedom and social equality for women.

The New York Ramblers, a team formed by gay men in the United States, was a soccer team that broke the norms of 'normality'.

They were founded in the early 1980s, when discrimination against homosexuals was severe, with the recognition that “sexual minorities also need a safe space where they can enjoy soccer.”

Despite many football clubs having roots in working-class and progressive politics, football stadiums around the world have long been rife with homophobia.

Because football fans are overwhelmingly male and the sport has traditionally emphasized strong masculinity, the most common insult heard on the pitch was mocking opposing players for being gay.

When the Ramblers were banned from the mainstream leagues, they joined their own independent gay league organization, leading international exchanges and growing into a social movement community that fought against exclusion based on sexual orientation, establishing themselves as a pioneer in gay football teams that continues to this day.

If soccer is a mirror reflecting society,

What kind of society are we seeing now?

The originality of 『Footbolitika』 lies in its way of reading football history as political history.

While many books cover football tactics, stars, and match results, the author of this book starts with the fundamental question: why and what kind of clubs exist?

Through football, he simultaneously illuminates the history of power and resistance, empire and colonization, men and women, capital and solidarity.

Moreover, this book does not simply restore the past.

It sharply exposes the structural problems of today's soccer and world politics, including the "sportswashing" of the Qatar World Cup, Saudi Arabian investment, and the gender equality debate surrounding women's soccer.

While pointing out the reality that football has become a tool for laundering the image of capital and state power, he still finds the possibility of solidarity and liberation within it.

Moreover, this book possesses both academic depth and popularity.

Academically, it follows the sociological tradition of Norbert Elias and Ignacio Ramone, and in terms of narrative, it adopts a vivid report structure like a documentary.

Each chapter's club may seem like a small fragment, but when taken together, they form a complete 'political landscape of modern and contemporary world history.'

Another feature is that it deals with the ‘politics of collective memory’ through soccer.

Each club embodies the memory of a specific group – the city's workers, minorities, women, and refugees – and elevates their voices to the center of society.

Football was the most popular language for the oppressed to express themselves, and in itself was an art of resistance.

Therefore, reading this book is not just about 'knowing soccer', but about gaining a new understanding of how the world works.

For political scientists, it will be a microscopic case study of popular politics, for social activists, it will be a language of solidarity, and for soccer fans, it will be a text that allows them to reflect on the roots of their passion.

“The history of football has always been the history of humanity,” says author Ramon Uzal.

For readers who wish to hear the cheers outside the stadium and the voice of the times contained within those cheers, this book will be an excellent guide.

Proving that the history of football is the history of human freedom and solidarity

The most intelligent and passionate world history

"Futbolitika" is a world historical work exploring the intertwining of football and politics, written by Catalan Spanish historian Ramón Uzal.

The author refutes the common belief that “soccer has nothing to do with politics,” and offers a new perspective on world history through the history of soccer.

The title of the book, Futbolitica, is a portmanteau of the words ‘football’ (futbol) and ‘politics’ (politica), revealing that football is more than just a game; it is a social and political phenomenon.

Since the birth of modern football in industrialised Britain in the 19th century, clubs have symbolised the identity of cities and communities, sometimes as a resistance to dictatorship, and sometimes as a tool of power.

Through the case studies of 55 clubs around the world, including England, France, Spain, the Balkans, the Middle East, Africa, and South America, Usal traces how football has functioned as a 'total social fact'.

This is not a general list of sports history, but rather a task of reading the structure of modern and contemporary political history through soccer.

By analyzing the social context in which the club was born, the history of oppression and liberation, and the politics of solidarity created by fan culture, the author demonstrates that the stadium is a microcosm of society.

This book intersects two currents in particular: 'how football was used by power' and 'how football resisted power'.

Dissecting the history of oppression and resistance, class and identity, gender and colonization, capital and solidarity surrounding football, it reconstructs the history of football as a microscopic record of world politics, including the political confrontation between Barcelona and Real Madrid, the incident where Liverpool fans became a symbol of resistance against the Thatcher government, the case of football becoming a place for independence movements in colonial Africa, and even the modern phenomenon of 'sportswashing' where capital and image politics combine.

This book, which crosses the history of football, politics, and culture, allows us to understand the author's argument that football always illuminates the deepest rifts in society.

The stadium became the only space of freedom against imperialism and dictatorship.

Power may have the ball, but the game has always belonged to the people.

Among the nine chapters in this book, categorized by region, the most prominent of the football clubs are the people's teams that resisted imperialism and dictatorship.

Football has often been used as a means to legitimize dictatorships, but it is remembered more as a language of resistance than as a language of power.

Spain's Franco tried to use Real Madrid, Portugal's dictator Salazar tried to overcome international isolation with SL Benfica, Italy's fascist Mussolini (Juventus FC), Romania's Ceaușescu (Steaua Bucharest), and Chile's Pinochet (Colo-Colo) also used football clubs as propaganda tools, but the people have always found freedom in the stadium and made football their own history.

In 1939, when the Spanish Civil War ended and Franco came to power, the Catalan language and culture were banned.

And Barcelona has been identified as a 'stronghold of separatism'.

Franco tried to integrate FC Barcelona into his system, but the club took the opposite path.

At the home stadium, Camp Nou, Catalan flags waved secretly instead of Spanish ones, and the crowd sang in the suppressed language of Catalan.

It was not a stadium, but the last refuge of an oppressed language.

While Real Madrid was used as a 'sports diplomacy tool' by the Franco regime, Barcelona became a symbol of civil resistance.

Even today, decades after Franco's death, Barcelona is still called “Catalonia on the pitch.”

Portugal's right-wing government, Estado Novo, faced massive resistance at football stadiums.

The Académie de Coimbra, a university student association founded in the central city of Coimbra, staged a violent protest during the 1969 Portuguese Cup final.

Despite the football federation banning the Coimbra team's black armbands and the government deploying a large police force around the stadium, the final was filled with anti-dictatorship flags and banners, and the stadium was filled with spectators chanting along with the protesting students, protecting them.

Another famous scene in 1990 in Zagreb, Croatia, was when the Dinamo Zagreb captain kneed a Serbian policeman who was assaulting a Croatian fan.

This day marked the beginning of the violent struggle for Croatia's freedom and independence.

Teams from displaced minorities and colonies have made football stadiums their territory.

During the colonial era, Racing Universitaire Algiers, where French and Algerian players played together in Algeria, was ostensibly a 'team of unity'.

However, in the French mainland league, they were treated as 'second-class citizens'.

The young man who grew up in this contradiction was Albert Camus, a philosopher and goalkeeper.

Camus recalled, “I learned morality and humanity on the soccer field.”

There is also the Al-Wehdat SC, which is made up entirely of Palestinian refugees.

The team was founded in a refugee camp in Amman, Jordan.

The Jordanian government was wary of the team's nationalism, but fans waved Palestinian flags at every game.

Their cries were not mere cheers, but a declaration of existence.

Football of the era born under the factory chimney,

Sustainable football against modern capitalism

Football has also served as a political language of solidarity and liberation against oppression, inequality, and discrimination.

『Footbolitika』 analyzes that Liverpool FC was a space for workers' solidarity in Liverpool, England in the 1980s, the heart of neoliberalism.

When the Thatcher government's neoliberal reforms drove workers in industrial cities into layoffs and poverty, the football stadium was their only community space, and the red uniforms were their pride and a symbol of survival.

This has made opposition to the Conservative government a core part of fan identity.

Fans chanted anti-Thatcher slogans in solidarity with various social movements in Liverpool.

In Turin, Italy, where Juventus FC, a club founded by Fiat Capital, is holding on, there is also Torino FC, a team created by factory workers.

The conflict between labor and capital within a city was symbolized by soccer. The stands in Turin were filled with fans in overalls, and the stadium's chants resembled labor union slogans.

The fascist regime even changed the team's name to 'Torino Fiat' in 1944, but the attempt to maintain dictatorship through football ended in failure.

Juventus FC has the upper hand in terms of sporting achievements, but Torino FC remains the most beloved team in the Piedmontese capital.

This is because the historical memory of the club once enabling workers to defeat their employers still lingers strongly.

Rayo Vallecano, founded in 1924 in Vallecas, a working-class area on the outskirts of Madrid, Spain, is also presented as a symbolic model of a working-class community fighting against the football of power and capital.

Because the area's population is largely comprised of low-income workers and immigrants, the club has harbored a spirit of resistance from the beginning.

In a commercialised environment where the Spanish top division is named after banks, the club maintains a sense of community and class consciousness, even recently helping elderly people forced out by bank debt.

They were the only band to join the general strike against the government's labour market 'reforms' in 2010, and their fan club also actively participated in the general strike protests against the EU-led austerity measures in 2012.

Although small in size, Rayo Vallecano is a club that has retained a dignity that many of its rivals have lost, a working-class team proud of its roots.

The question posed by a British vegan club about 'what does football consume?' is also interesting.

The case of Forest Green Rovers, which rejected the logic of capital and created a new football culture centered on the environment and life, shows that football can become a platform for social movements.

In an era when oil capital dominated the league and fans cheered with disposable plastic cups, Forest Green Rovers, a small league club, promoted itself as a 'sustainable club'.

All meals were vegan, the stadium switched to solar power, and the grass was managed organically.

The book praised Forest Green Rovers as an iconic example of how football can contribute to the global fight against the climate crisis.

How soccer learns equality

Stadium owners who have won the 'right to participate'

In the summer of 2023, the Spanish women's national team won the World Cup for the first time.

But there was one scene on the podium that caused a bigger stir than the trophy.

Spanish Football Federation president Luis Rubiales kissed star player Genifer Hermoso without his consent.

Spanish society was instantly in an uproar.

“We won, but we are not yet equal.” After the incident, Rubiales resigned and the federation pledged to bring about substantial equality between the men’s and women’s teams.

The author sees this incident as showing that football is inherently a political phenomenon.

While women's football has enjoyed a surge in public attention and acclaim since 2017, female players remain far from being treated equally, and the high media attention paid to the women's league demonstrates that the fight for women's empowerment and gender equality is being waged through football.

British Ladies FC, introduced in this book as the world's first women's soccer team, was formed in England in 1895 and sent a message to a male-dominated society that women could also play on the field.

The founding goal was to go beyond soccer and advocate for women's social equality and suffrage.

The press ridiculed them and accused them of 'losing their feminine dignity', but their London debut drew a crowd of 10,000, and the women challenged dress codes by performing without corsets.

Despite social criticism, the team played over 100 exhibition games throughout the year, paving the way for women's liberation.

British Ladies FC is considered the first sports political act to demand physical freedom and social equality for women.

The New York Ramblers, a team formed by gay men in the United States, was a soccer team that broke the norms of 'normality'.

They were founded in the early 1980s, when discrimination against homosexuals was severe, with the recognition that “sexual minorities also need a safe space where they can enjoy soccer.”

Despite many football clubs having roots in working-class and progressive politics, football stadiums around the world have long been rife with homophobia.

Because football fans are overwhelmingly male and the sport has traditionally emphasized strong masculinity, the most common insult heard on the pitch was mocking opposing players for being gay.

When the Ramblers were banned from the mainstream leagues, they joined their own independent gay league organization, leading international exchanges and growing into a social movement community that fought against exclusion based on sexual orientation, establishing themselves as a pioneer in gay football teams that continues to this day.

If soccer is a mirror reflecting society,

What kind of society are we seeing now?

The originality of 『Footbolitika』 lies in its way of reading football history as political history.

While many books cover football tactics, stars, and match results, the author of this book starts with the fundamental question: why and what kind of clubs exist?

Through football, he simultaneously illuminates the history of power and resistance, empire and colonization, men and women, capital and solidarity.

Moreover, this book does not simply restore the past.

It sharply exposes the structural problems of today's soccer and world politics, including the "sportswashing" of the Qatar World Cup, Saudi Arabian investment, and the gender equality debate surrounding women's soccer.

While pointing out the reality that football has become a tool for laundering the image of capital and state power, he still finds the possibility of solidarity and liberation within it.

Moreover, this book possesses both academic depth and popularity.

Academically, it follows the sociological tradition of Norbert Elias and Ignacio Ramone, and in terms of narrative, it adopts a vivid report structure like a documentary.

Each chapter's club may seem like a small fragment, but when taken together, they form a complete 'political landscape of modern and contemporary world history.'

Another feature is that it deals with the ‘politics of collective memory’ through soccer.

Each club embodies the memory of a specific group – the city's workers, minorities, women, and refugees – and elevates their voices to the center of society.

Football was the most popular language for the oppressed to express themselves, and in itself was an art of resistance.

Therefore, reading this book is not just about 'knowing soccer', but about gaining a new understanding of how the world works.

For political scientists, it will be a microscopic case study of popular politics, for social activists, it will be a language of solidarity, and for soccer fans, it will be a text that allows them to reflect on the roots of their passion.

“The history of football has always been the history of humanity,” says author Ramon Uzal.

For readers who wish to hear the cheers outside the stadium and the voice of the times contained within those cheers, this book will be an excellent guide.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 22, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 420 pages | 532g | 142*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791186036884

- ISBN10: 1186036885

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)