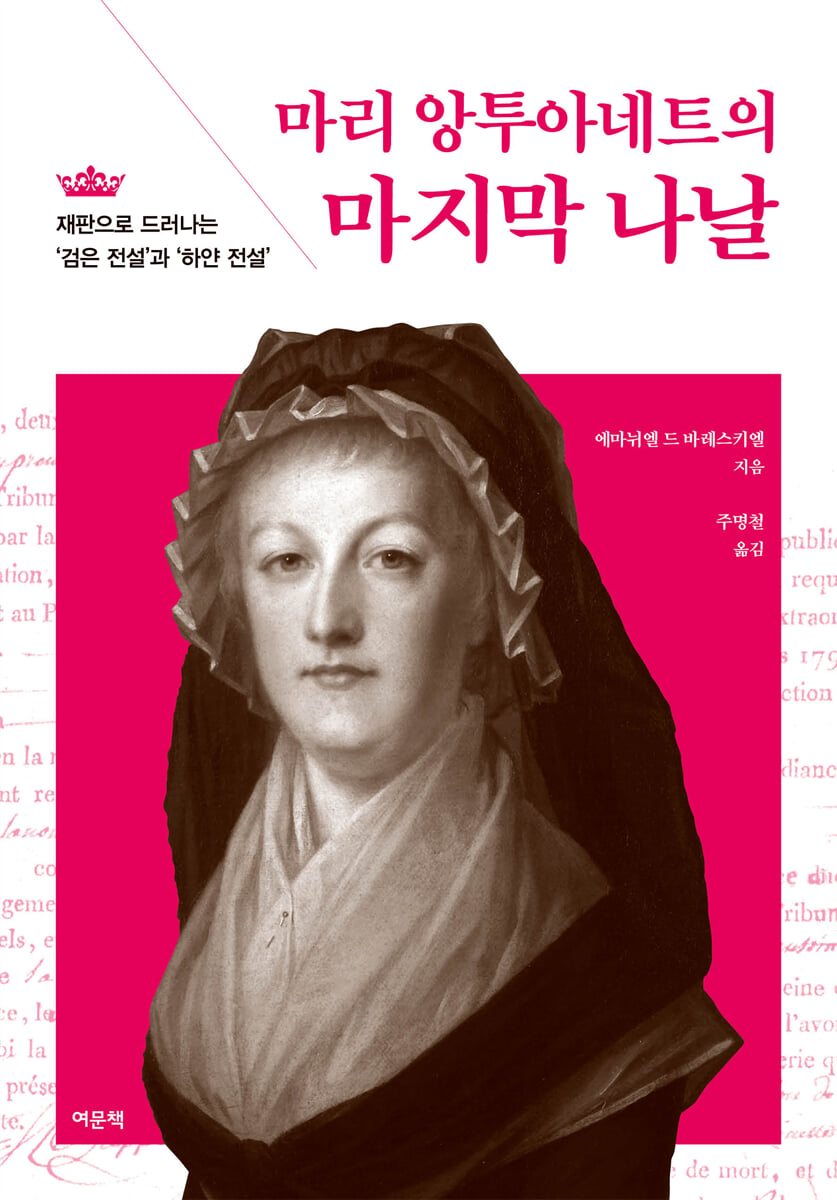

Marie Antoinette's last days

|

Description

Book Introduction

The Trial and Execution of Marie Antoinette: A Look at Human Nature and the Nature of Justice

What did the revolutionary courts look like during the French Revolution, one of the greatest turning points in modern world history? From our modern perspective, it might seem somewhat surprising that the jury system already existed and trials were conducted publicly.

However, we must recognize the limitation that the majority of the jurors had a very close relationship with the judge.

“Everyone felt fear even in their own homes.

If you laughed, you were accused of celebrating the Republic's defeat, and if you cried, you were accused of mourning the Republic's success.

As the testimony that “soldiers would burst into the house at any moment and discover the plot” attests, the period in which this book is set “was not yet the midnight of the Reign of Terror, but was already approaching the early evening.”

Why is the French Revolution of 1789 still so revered? Above all, it was a momentous event—one that, in the atmosphere of Europe at the time, was almost unimaginable. It saw the public execution of the king, queen, countless nobles, and even Robespierre, the man who had orchestrated the Reign of Terror, by guillotine. The once-firm class order collapsed, ushering in an era of "popular sovereignty."

This book is a tragic period drama in which Marie Antoinette, who was forced to remain bound to the Old World longer because of her status as a "queen" during a time of great chaos when sovereignty suddenly passed from the king to the people, plays the lead role, and the prosecution Fouquier-Tinville and the presiding judge Hermann play supporting roles, and many other characters appear, including the painter Châtelet, the shoemaker Simon, and the newspaper publisher Hébert, as well as key jurors and witnesses, and many others, from the Swedish nobleman Fersen, who truly loved Marie Antoinette until his death, to the queen's family and maids of honor, and Henri Sanson, the person in charge of the guillotine execution.

What did the revolutionary courts look like during the French Revolution, one of the greatest turning points in modern world history? From our modern perspective, it might seem somewhat surprising that the jury system already existed and trials were conducted publicly.

However, we must recognize the limitation that the majority of the jurors had a very close relationship with the judge.

“Everyone felt fear even in their own homes.

If you laughed, you were accused of celebrating the Republic's defeat, and if you cried, you were accused of mourning the Republic's success.

As the testimony that “soldiers would burst into the house at any moment and discover the plot” attests, the period in which this book is set “was not yet the midnight of the Reign of Terror, but was already approaching the early evening.”

Why is the French Revolution of 1789 still so revered? Above all, it was a momentous event—one that, in the atmosphere of Europe at the time, was almost unimaginable. It saw the public execution of the king, queen, countless nobles, and even Robespierre, the man who had orchestrated the Reign of Terror, by guillotine. The once-firm class order collapsed, ushering in an era of "popular sovereignty."

This book is a tragic period drama in which Marie Antoinette, who was forced to remain bound to the Old World longer because of her status as a "queen" during a time of great chaos when sovereignty suddenly passed from the king to the people, plays the lead role, and the prosecution Fouquier-Tinville and the presiding judge Hermann play supporting roles, and many other characters appear, including the painter Châtelet, the shoemaker Simon, and the newspaper publisher Hébert, as well as key jurors and witnesses, and many others, from the Swedish nobleman Fersen, who truly loved Marie Antoinette until his death, to the queen's family and maids of honor, and Henri Sanson, the person in charge of the guillotine execution.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Act 1 In Prison

Act 2 Foreigner

Act 3 Defendant

Act 4 'The Knight of Death'

Epilogue

Reviews

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

Image caption

feedstuff

Search

Act 2 Foreigner

Act 3 Defendant

Act 4 'The Knight of Death'

Epilogue

Reviews

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

Image caption

feedstuff

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

If there was any truth in the trial, it was the truth of human nature, which is always changing and volatile.

(Omitted) The reason I mention Chatelet first is probably because he is the person who best reveals the main contradiction of the members of the court.

He was somewhere between enthusiasm and passion, fear, impulse and reason, truth and ambition, and hatred.

Somewhere between the wounds of pride, the hesitation and timidity of people, and the solace of certainty without regret in an idealized black-and-white world.

In the end, they became good people and bad people, patriots and traitors.

It was a revolution and a counter-revolution.

All of this inevitably led to extremism and anger.

--- p.34

They've already gone too far.

Things would get worse later, when both her [Marie Antoinette's] supporters and opponents would re-imagine her trial.

The supporters wanted to clearly show the scars of the sacrifice he had made.

On the other hand, for entirely different reasons, his opponents were no longer willing to treat him with lenience.

They tried their best to make his dark soul known to the world, emphasizing his prematurely aged and hideous appearance without a mask or makeup.

From the revolutionaries' perspective, Marie Antoinette's physical decline was like a sudden revelation of the vices of female nature.

In other words, this trial was, above all, a trial of imagination.

This is the crux of this drama.

--- p.66

Just as the queens of the past were almost godlike beings, the feeling of equality has now become for the guards not just a right, but a kind of revenge, and perhaps even a pleasure that makes them forget who they are.

To the supporters of the 'unlucky captive', it was, of course, an 'act of insulting misfortune'.

--- p.86

She was destined not merely to be a queen, but to be the vessel [of the child], the pledge and the collateral, and the central piece of the new European problem that was being created inexorably.

He was already the living embodiment of what was called a 'strange alliance' among hostile forces.

This whole thing felt like a trap.

Marie Antoinette was already a victim of family interests and European politics in 1770, long before she became a hostage to the Revolution.

--- p.114

The jury of October 14 was clearly composed of active and revolutionary sans-culottes from the People's Assembly.

Although sans-culottes meant the people, in reality they were only half the people, a minority representing only about 5 percent of the 26 million French population in 1789.

If they symbolize anything, it is themselves.

As we saw earlier, the jurors were carefully selected by the prosecution before the trial.

The majority were artisans, professionals, and members of the Parisian professional societies of the lower bourgeoisie.

Some were born in Paris, but most settled there shortly before 1789.

This social diversification and the occupational changes and reorganizations in Paris in the late 18th century can be seen as partly the roots of the revolution.

--- pp.158-159

In conclusion, Marie Antoinette found her husband boring.

His lecteur, the faithful priest Vermond, frankly told her that she did not love her husband, and that it would be difficult for her to act otherwise if she had known the king's character.

--- pp.196-197

Marie Antoinette became queen of the 'women's worldmundus muliebris'.

In this refuge called 'the world of women', forms and styles, the madness of Trianon and the dairy farm of Rambouillet, waterfalls and grottoes, memories of purity, elegance, surprise, nature and ruins were born.

All of this was a woman's desire, and it caused great shock and anger among philosophers and devout believers of the time, as well as those who advocated male virtue and preferred Rome or Sparta to Athens.

(syncopation)

The paradox is that in all this the 'Austrian woman' is more French than ever.

(Omitted) In the end, what we call ‘French taste’ today was Marie Antoinette.

--- pp.200-201

The lawyers whom Fouquie reluctantly chose were also those who had been assigned to the Revolutionary Court since its creation, and belonged essentially to the same social class as the judges they faced when they argued.

Support for the ideals of 1789 was not a question of any particular region or class, nor was it determined by social characteristics such as whether one belonged to the Third Estate or the privileged classes.

The revolution deeply penetrated the lives of all social classes, from the humblest to the highest, even within the family.

This phenomenon was repeated in the great crises of 1815, 1940, and 1945.

--- pp.262-263

Reading the surviving fragments of Chauveau-Lagarde's defense, we see that the brilliant criminal lawyer was keen to point out the woefully weak evidence of the prosecution.

He opened the door like this.

“While the indictment certainly appears serious, it is unfortunate that the evidence is so questionable.” He began by assuming that all the proceedings were normal, but soon completely overstepped the boundaries of procedure and shifted the trial to a political dimension.

“The defendant’s misfortune is that she became a queen.

That fact alone is enough to make Republicans conclude that he cannot be just, and you too may stray from your sacred impartiality and become biased.”

The problem was right here.

Shobo knew it.

He earnestly implored the jurors to set aside their prejudices and consider the indictment with him, piece by piece.

But did he defend women and mothers? I don't think so.

He would probably focus on the most specific allegations and hide behind the law and rights.

The problem was that the court didn't care about it.

(Omitted) The reason I mention Chatelet first is probably because he is the person who best reveals the main contradiction of the members of the court.

He was somewhere between enthusiasm and passion, fear, impulse and reason, truth and ambition, and hatred.

Somewhere between the wounds of pride, the hesitation and timidity of people, and the solace of certainty without regret in an idealized black-and-white world.

In the end, they became good people and bad people, patriots and traitors.

It was a revolution and a counter-revolution.

All of this inevitably led to extremism and anger.

--- p.34

They've already gone too far.

Things would get worse later, when both her [Marie Antoinette's] supporters and opponents would re-imagine her trial.

The supporters wanted to clearly show the scars of the sacrifice he had made.

On the other hand, for entirely different reasons, his opponents were no longer willing to treat him with lenience.

They tried their best to make his dark soul known to the world, emphasizing his prematurely aged and hideous appearance without a mask or makeup.

From the revolutionaries' perspective, Marie Antoinette's physical decline was like a sudden revelation of the vices of female nature.

In other words, this trial was, above all, a trial of imagination.

This is the crux of this drama.

--- p.66

Just as the queens of the past were almost godlike beings, the feeling of equality has now become for the guards not just a right, but a kind of revenge, and perhaps even a pleasure that makes them forget who they are.

To the supporters of the 'unlucky captive', it was, of course, an 'act of insulting misfortune'.

--- p.86

She was destined not merely to be a queen, but to be the vessel [of the child], the pledge and the collateral, and the central piece of the new European problem that was being created inexorably.

He was already the living embodiment of what was called a 'strange alliance' among hostile forces.

This whole thing felt like a trap.

Marie Antoinette was already a victim of family interests and European politics in 1770, long before she became a hostage to the Revolution.

--- p.114

The jury of October 14 was clearly composed of active and revolutionary sans-culottes from the People's Assembly.

Although sans-culottes meant the people, in reality they were only half the people, a minority representing only about 5 percent of the 26 million French population in 1789.

If they symbolize anything, it is themselves.

As we saw earlier, the jurors were carefully selected by the prosecution before the trial.

The majority were artisans, professionals, and members of the Parisian professional societies of the lower bourgeoisie.

Some were born in Paris, but most settled there shortly before 1789.

This social diversification and the occupational changes and reorganizations in Paris in the late 18th century can be seen as partly the roots of the revolution.

--- pp.158-159

In conclusion, Marie Antoinette found her husband boring.

His lecteur, the faithful priest Vermond, frankly told her that she did not love her husband, and that it would be difficult for her to act otherwise if she had known the king's character.

--- pp.196-197

Marie Antoinette became queen of the 'women's worldmundus muliebris'.

In this refuge called 'the world of women', forms and styles, the madness of Trianon and the dairy farm of Rambouillet, waterfalls and grottoes, memories of purity, elegance, surprise, nature and ruins were born.

All of this was a woman's desire, and it caused great shock and anger among philosophers and devout believers of the time, as well as those who advocated male virtue and preferred Rome or Sparta to Athens.

(syncopation)

The paradox is that in all this the 'Austrian woman' is more French than ever.

(Omitted) In the end, what we call ‘French taste’ today was Marie Antoinette.

--- pp.200-201

The lawyers whom Fouquie reluctantly chose were also those who had been assigned to the Revolutionary Court since its creation, and belonged essentially to the same social class as the judges they faced when they argued.

Support for the ideals of 1789 was not a question of any particular region or class, nor was it determined by social characteristics such as whether one belonged to the Third Estate or the privileged classes.

The revolution deeply penetrated the lives of all social classes, from the humblest to the highest, even within the family.

This phenomenon was repeated in the great crises of 1815, 1940, and 1945.

--- pp.262-263

Reading the surviving fragments of Chauveau-Lagarde's defense, we see that the brilliant criminal lawyer was keen to point out the woefully weak evidence of the prosecution.

He opened the door like this.

“While the indictment certainly appears serious, it is unfortunate that the evidence is so questionable.” He began by assuming that all the proceedings were normal, but soon completely overstepped the boundaries of procedure and shifted the trial to a political dimension.

“The defendant’s misfortune is that she became a queen.

That fact alone is enough to make Republicans conclude that he cannot be just, and you too may stray from your sacred impartiality and become biased.”

The problem was right here.

Shobo knew it.

He earnestly implored the jurors to set aside their prejudices and consider the indictment with him, piece by piece.

But did he defend women and mothers? I don't think so.

He would probably focus on the most specific allegations and hide behind the law and rights.

The problem was that the court didn't care about it.

--- pp.266~267

Publisher's Review

The political trial of the century ended in just three days. Find the truth!

How fair and just are the trials in our society today?

During the French Revolution, the trial and execution of Marie Antoinette took only three days, from October 14 to 16, 1793.

He was already sentenced to death before he was even formally tried.

This was, of course, the trial of the queen, but also the trial of a foreign woman, and the trial of a woman and her mother.

◆ Revolution, like two sides of a coin, a fateful community swept up in tragedy within its whirlpool.

The author, Emmanuel de Baresquiel, who is being introduced in Korea for the first time, is a descendant of a noble family, as his name suggests.

However, one should not read this book with the preconceived notion that it was written from an anachronistic royalist perspective.

The author, who received the Prix Gobert of the Académie Française in 1991, eight years before being appointed professor at the École des Hautes Études des Arts et ...

Why did he write this book, and what did he want to say through it?

Because I thought that anyone who wants to understand ourselves today must know that period, which symbolically shows the beginning and excesses of the revolution.

I wanted to show the bright and dark sides of the revolution, but also to say that they can never be separated.

(Omitted) From October 14 to 16, 1793, here, two societies, two systems of representation, two worlds clashed in miniature and engaged in a bizarre battle.

It was a more striking sight than the king's trial.

Because the antagonists are more clearly and distinctly depicted.

Revolution and counter-revolution.

Male and female.

Two sovereignties, two legitimacy, and also the words fatherland, betrayal, virtue, and conspiracy, whose meanings keep changing depending on who they are applied to.

Two worlds that are completely opposed to each other and can never be reconciled, two worlds that seemingly coexist, communicate, and interact, but do not understand each other.

Such autism leads directly to death.

The death of Marie Antoinette and her friends, the death of her accusers and judges.

I was captivated by this community of tragic fate.

We must be honest and admit it.

We built our republic on countless corpses, and then we built democracy.

(Pages 352-353)

There is much written about Marie Antoinette, but little about her trial.

In the early 19th century, many studies were published that treated his last moments with sacralism, almost entirely from his own perspective.

Recognizing these limitations, the author devoted extraordinary effort to researching, excavating, and compiling a wide range of materials, including contemporary trial records, especially unpublished hearing records, and even letters unearthed later, ultimately completing a three-dimensional, highly detailed, and balanced view of contemporary history that had never been seen before.

As a result of this achievement, he achieved the feat of receiving prestigious French literary awards and biographer awards.

◆ “The revolution is not only a victory of equality over the privileged,

“It was also men’s revenge on the women’s world.”

While the American diplomat Gouverneur Morris had earlier criticized Louis XVI's impotence, calling him "utterly useless," he was astonished at the strength and decisiveness of the queen, unlike the "good" king (a critical term for weakness at court).

The France he encountered in 1789 was a 'country of women.'

Talleyrand, one of the leading figures of the time, also emphasized the presence of women everywhere on the eve of the revolution, saying that women dictated the atmosphere and dominated customs, language, tastes, and even politics.

It was also said that in the salons of Paris, young women could freely discuss government decisions and the most complex administrative operations.

The author adds, “Today we live in an era of gender equality, but back then it was a sad, indifferent, and procedural era unlike any other.”

The atmosphere changed completely when the revolution broke out in France, a country so free, and when war was declared against Austria in 1792, and when France suffered further defeats against Austria the following year, the queen was imprisoned and felt more guilty than ever.

The Austrian queen Marie Antoinette was subjected to countless insults and outrageous rumors, including the Austrian mule, the evil Austrian bitch, the Austrian vicious female tiger drenched in the blood of her victims, the Austrian hen, and the legitimate wife.

The author says, “At no time in history has any woman been the object of so much hatred.

“Everything he said, did, or touched was hated,” “It is clear that behind these attacks lies a jealousy that he never harbored toward the king.

“Louis XVI was only wrong in symbolizing the monarchy, while the queen was the embodiment of its crimes,” he diagnoses.

“Ultimately, in the eyes of the revolutionaries, Marie Antoinette’s true crime was that she took the place of a man, transcending the role and position of a woman.”

The author tells us how strong the misogyny was at the time.

Women's temperament is neurotic, so they easily fall into 'overexcitement', which is fatal to freedom and public affairs.

Women represent mistakes and disorder.

The moral education of women is “almost fruitless.” This idea reappears repeatedly in numerous literary works of the revolutionary period.

One journalist wrote:

“As we say every day, the customs of French women have not yet survived the Revolution.”

Therefore, women must be sent back to their homes or silenced.

Because they are potentially counter-revolutionary.

Marie Antoinette's trial was between the trials of women such as Charlotte Corday, Madame de Roland, and Olympe de Gouges.

(Page 230)

Marie Antoinette's trial, which felt like a "wide-ranging social subversion operation"

In addition to various documents, many paintings depicting the queen in vulgar and obscene terms clearly reveal the stereotypes that revolutionary men wanted to see the queen as a dominant, subversive, and dangerous woman.

This misogyny was a wound that could not be healed for a long time, and Marie Antoinette had to stand before a jury and a judge with these tendencies.

Marie Antoinette's trial was unlike any other.

It wasn't just because it was the queen's trial.

It was a moment and an opportunity for two very different worlds to clash violently: a world that was disappearing and a new world being born amidst violence.

Not only did the two worlds not listen to each other, but they could only be saved by eliminating the other, and they had long established valid reasons for their inability to reconcile.

On one side there was the republic, on the other there was the monarchy, the royal court, the customs and manners.

This trial was also a woman's trial, and a mother's trial.

Finally, there was the trial of a foreigner.

If this trial has any reality, it is the reality of imagination.

So this trial was unique.

(Page 28)

All trials proceeded with poor evidence, and witnesses who could not provide adequate evidence sought an opportunity to seek revenge for their past identities.

Witnesses and jurors said, “In a matter of months, he went from being a meaningless and ordinary man to being able to save or kill thousands of his comrades.

In short, they saw the woman who had once been their queen only as a figure in a print, and they could save her or execute her regardless of the distance between them.

This was precisely the meaning of the Marie Antoinette trial.

It was the revenge of an ordinary small business owner, the revenge of the extraordinary and the inaccessible, the revenge of the ordinary triumphing over the long-unthinkable.

(Omitted) To understand them, we must consider how ecstatic they must have been to wield such immense power in a situation they were not prepared for.” (p. 162)

◆ The first case of a sex crime trial in history

Marie Antoinette's life was extraordinary from the start.

Born an Archduchess of the Austrian Habsburg family and becoming the queen of France, one of the most powerful nations in the world, she possessed the innate elegance of an aristocratic physique and bearing, high self-esteem, and even the honor of a knight in the armor of courage.

The revolutionary people had anticipated the queen's power and stubbornness very early on and regarded her as an obstacle to the revolution.

“There is only one man by the king’s side, and that is his wife.” Everyone knew this saying by the famous Count Mirabeau, and in the end the revolutionaries decided to make the queen their victim.

For four years after the revolution began, Marie Antoinette lived under constant threat to her life.

They openly sought to find and kill Marie Antoinette when they rebelled against the Tuileries Palace in October 1789 and again on June 20, 1792.

“Where are you, Austrian? Let’s cut off his head!”

After being imprisoned in the Tower of the Temple with Louis XVI on August 23, 1792, and transferred to the Conciergerie prison seven months later, Marie Antoinette suffered even more than the horrific deaths of her husband and daughter.

In the courtroom, she was denied even her role as a mother and had no choice but to hear the horrific accusation of having committed incest with her eight-year-old son.

According to the author, “To further damage the honor of women, his judges came up with the wicked idea of attacking even the role of mother.

(Omitted) The revolutionaries knew this well.

“To touch the mother is to touch the sanctity of the royal lineage, to sever the connection between sanctity and lineage, and with it to once again execute the monarchy.”

This led to the devastating accusations of Hébert, the publisher of the Parisian newspaper "Mr. Duchenne," which boasted a huge circulation at the time.

“The two women [the queen and the prince’s aunt] often let the child [the crown prince] sleep between them, where they frequently committed acts of the most insane debauchery, and there is no doubt, as the café’s son [the crown prince] tells us, that there was incest between mother and son.” Hébert went even further, adding the hideous and horrifying explanation that “Marie Antoinette slept with her son not for mere pleasure, but also with a wicked political intention to ‘excite his flesh’ and thus gain better control over him as a young boy!”

The author offers a sharp criticism of this.

“It is difficult to imagine how sick a brain must be to plot such a diabolical scheme to attack Marie Antoinette by attacking the thing most precious to her.

(Omitted) Did he look the defendant in the eye as he said this? At the very least, the courage to pour out shocking and horrific stories in front of him is nothing more than an excuse for the 'salauds.'

Meanwhile, Marie Antoinette, who was so shocked that she burst into tears, barely managed to reply:

“Is there a single mother who doesn’t shudder at the thought of these terrible things?”

Marie Antoinette was forced to face such absurd and inhumane accusations, and was executed on the guillotine after a three-day trial that was completely absurd.

Marie Antoinette, a victim of the 'Black Legend', was also followed by the 'White Legend' even before her execution.

Some people found something 'supernatural' in Marie Antoinette's courage, as she maintained an upright posture without changing her expression even when her life was threatened right before her eyes, while others, who desperately tried to soak her blood shed on the execution ground with a handkerchief, considered her a martyr.

But legends are just legends, and 232 years after Marie Antoinette's death, we should face the circumstances and truth of that time and use it as an opportunity to reflect on ourselves and society through the diverse human figures.

“Tragedy always hides in the folds of what is not seen.”

Professor Joo Myeong-cheol, who translated this book, explains its significance as follows:

How legal and just was Marie Antoinette's trial? What use is it to ask such a question from today's perspective? As in any other era, but even more so during the Reign of Terror, politics superseded law.

The trial of Marie Antoinette is a prime example.

Emmanuel de Baresquiel uses Marie Antoinette as his entrance to lead us into the Revolutionary Court and shows us how the courts functioned at that time.

The atmosphere of the prison and courtroom, made even more gloomy by the lack of light due to the limitations of the time, the psychology of the queen who was dragged there, the sociology of the jury and witnesses, and the mechanisms of the reign of terror were all brought to life through the author's insight and meticulous yet leisurely descriptions.

The reader can feel the dust, sounds, and even smells floating in the darkness as Marie Antoinette moves from the Tower of the Temple to the Conciergerie on August 2, 1793, completes simple formalities, and enters the cell she is assigned to.

(Page 375)

How fair and just are the trials in our society today?

During the French Revolution, the trial and execution of Marie Antoinette took only three days, from October 14 to 16, 1793.

He was already sentenced to death before he was even formally tried.

This was, of course, the trial of the queen, but also the trial of a foreign woman, and the trial of a woman and her mother.

◆ Revolution, like two sides of a coin, a fateful community swept up in tragedy within its whirlpool.

The author, Emmanuel de Baresquiel, who is being introduced in Korea for the first time, is a descendant of a noble family, as his name suggests.

However, one should not read this book with the preconceived notion that it was written from an anachronistic royalist perspective.

The author, who received the Prix Gobert of the Académie Française in 1991, eight years before being appointed professor at the École des Hautes Études des Arts et ...

Why did he write this book, and what did he want to say through it?

Because I thought that anyone who wants to understand ourselves today must know that period, which symbolically shows the beginning and excesses of the revolution.

I wanted to show the bright and dark sides of the revolution, but also to say that they can never be separated.

(Omitted) From October 14 to 16, 1793, here, two societies, two systems of representation, two worlds clashed in miniature and engaged in a bizarre battle.

It was a more striking sight than the king's trial.

Because the antagonists are more clearly and distinctly depicted.

Revolution and counter-revolution.

Male and female.

Two sovereignties, two legitimacy, and also the words fatherland, betrayal, virtue, and conspiracy, whose meanings keep changing depending on who they are applied to.

Two worlds that are completely opposed to each other and can never be reconciled, two worlds that seemingly coexist, communicate, and interact, but do not understand each other.

Such autism leads directly to death.

The death of Marie Antoinette and her friends, the death of her accusers and judges.

I was captivated by this community of tragic fate.

We must be honest and admit it.

We built our republic on countless corpses, and then we built democracy.

(Pages 352-353)

There is much written about Marie Antoinette, but little about her trial.

In the early 19th century, many studies were published that treated his last moments with sacralism, almost entirely from his own perspective.

Recognizing these limitations, the author devoted extraordinary effort to researching, excavating, and compiling a wide range of materials, including contemporary trial records, especially unpublished hearing records, and even letters unearthed later, ultimately completing a three-dimensional, highly detailed, and balanced view of contemporary history that had never been seen before.

As a result of this achievement, he achieved the feat of receiving prestigious French literary awards and biographer awards.

◆ “The revolution is not only a victory of equality over the privileged,

“It was also men’s revenge on the women’s world.”

While the American diplomat Gouverneur Morris had earlier criticized Louis XVI's impotence, calling him "utterly useless," he was astonished at the strength and decisiveness of the queen, unlike the "good" king (a critical term for weakness at court).

The France he encountered in 1789 was a 'country of women.'

Talleyrand, one of the leading figures of the time, also emphasized the presence of women everywhere on the eve of the revolution, saying that women dictated the atmosphere and dominated customs, language, tastes, and even politics.

It was also said that in the salons of Paris, young women could freely discuss government decisions and the most complex administrative operations.

The author adds, “Today we live in an era of gender equality, but back then it was a sad, indifferent, and procedural era unlike any other.”

The atmosphere changed completely when the revolution broke out in France, a country so free, and when war was declared against Austria in 1792, and when France suffered further defeats against Austria the following year, the queen was imprisoned and felt more guilty than ever.

The Austrian queen Marie Antoinette was subjected to countless insults and outrageous rumors, including the Austrian mule, the evil Austrian bitch, the Austrian vicious female tiger drenched in the blood of her victims, the Austrian hen, and the legitimate wife.

The author says, “At no time in history has any woman been the object of so much hatred.

“Everything he said, did, or touched was hated,” “It is clear that behind these attacks lies a jealousy that he never harbored toward the king.

“Louis XVI was only wrong in symbolizing the monarchy, while the queen was the embodiment of its crimes,” he diagnoses.

“Ultimately, in the eyes of the revolutionaries, Marie Antoinette’s true crime was that she took the place of a man, transcending the role and position of a woman.”

The author tells us how strong the misogyny was at the time.

Women's temperament is neurotic, so they easily fall into 'overexcitement', which is fatal to freedom and public affairs.

Women represent mistakes and disorder.

The moral education of women is “almost fruitless.” This idea reappears repeatedly in numerous literary works of the revolutionary period.

One journalist wrote:

“As we say every day, the customs of French women have not yet survived the Revolution.”

Therefore, women must be sent back to their homes or silenced.

Because they are potentially counter-revolutionary.

Marie Antoinette's trial was between the trials of women such as Charlotte Corday, Madame de Roland, and Olympe de Gouges.

(Page 230)

Marie Antoinette's trial, which felt like a "wide-ranging social subversion operation"

In addition to various documents, many paintings depicting the queen in vulgar and obscene terms clearly reveal the stereotypes that revolutionary men wanted to see the queen as a dominant, subversive, and dangerous woman.

This misogyny was a wound that could not be healed for a long time, and Marie Antoinette had to stand before a jury and a judge with these tendencies.

Marie Antoinette's trial was unlike any other.

It wasn't just because it was the queen's trial.

It was a moment and an opportunity for two very different worlds to clash violently: a world that was disappearing and a new world being born amidst violence.

Not only did the two worlds not listen to each other, but they could only be saved by eliminating the other, and they had long established valid reasons for their inability to reconcile.

On one side there was the republic, on the other there was the monarchy, the royal court, the customs and manners.

This trial was also a woman's trial, and a mother's trial.

Finally, there was the trial of a foreigner.

If this trial has any reality, it is the reality of imagination.

So this trial was unique.

(Page 28)

All trials proceeded with poor evidence, and witnesses who could not provide adequate evidence sought an opportunity to seek revenge for their past identities.

Witnesses and jurors said, “In a matter of months, he went from being a meaningless and ordinary man to being able to save or kill thousands of his comrades.

In short, they saw the woman who had once been their queen only as a figure in a print, and they could save her or execute her regardless of the distance between them.

This was precisely the meaning of the Marie Antoinette trial.

It was the revenge of an ordinary small business owner, the revenge of the extraordinary and the inaccessible, the revenge of the ordinary triumphing over the long-unthinkable.

(Omitted) To understand them, we must consider how ecstatic they must have been to wield such immense power in a situation they were not prepared for.” (p. 162)

◆ The first case of a sex crime trial in history

Marie Antoinette's life was extraordinary from the start.

Born an Archduchess of the Austrian Habsburg family and becoming the queen of France, one of the most powerful nations in the world, she possessed the innate elegance of an aristocratic physique and bearing, high self-esteem, and even the honor of a knight in the armor of courage.

The revolutionary people had anticipated the queen's power and stubbornness very early on and regarded her as an obstacle to the revolution.

“There is only one man by the king’s side, and that is his wife.” Everyone knew this saying by the famous Count Mirabeau, and in the end the revolutionaries decided to make the queen their victim.

For four years after the revolution began, Marie Antoinette lived under constant threat to her life.

They openly sought to find and kill Marie Antoinette when they rebelled against the Tuileries Palace in October 1789 and again on June 20, 1792.

“Where are you, Austrian? Let’s cut off his head!”

After being imprisoned in the Tower of the Temple with Louis XVI on August 23, 1792, and transferred to the Conciergerie prison seven months later, Marie Antoinette suffered even more than the horrific deaths of her husband and daughter.

In the courtroom, she was denied even her role as a mother and had no choice but to hear the horrific accusation of having committed incest with her eight-year-old son.

According to the author, “To further damage the honor of women, his judges came up with the wicked idea of attacking even the role of mother.

(Omitted) The revolutionaries knew this well.

“To touch the mother is to touch the sanctity of the royal lineage, to sever the connection between sanctity and lineage, and with it to once again execute the monarchy.”

This led to the devastating accusations of Hébert, the publisher of the Parisian newspaper "Mr. Duchenne," which boasted a huge circulation at the time.

“The two women [the queen and the prince’s aunt] often let the child [the crown prince] sleep between them, where they frequently committed acts of the most insane debauchery, and there is no doubt, as the café’s son [the crown prince] tells us, that there was incest between mother and son.” Hébert went even further, adding the hideous and horrifying explanation that “Marie Antoinette slept with her son not for mere pleasure, but also with a wicked political intention to ‘excite his flesh’ and thus gain better control over him as a young boy!”

The author offers a sharp criticism of this.

“It is difficult to imagine how sick a brain must be to plot such a diabolical scheme to attack Marie Antoinette by attacking the thing most precious to her.

(Omitted) Did he look the defendant in the eye as he said this? At the very least, the courage to pour out shocking and horrific stories in front of him is nothing more than an excuse for the 'salauds.'

Meanwhile, Marie Antoinette, who was so shocked that she burst into tears, barely managed to reply:

“Is there a single mother who doesn’t shudder at the thought of these terrible things?”

Marie Antoinette was forced to face such absurd and inhumane accusations, and was executed on the guillotine after a three-day trial that was completely absurd.

Marie Antoinette, a victim of the 'Black Legend', was also followed by the 'White Legend' even before her execution.

Some people found something 'supernatural' in Marie Antoinette's courage, as she maintained an upright posture without changing her expression even when her life was threatened right before her eyes, while others, who desperately tried to soak her blood shed on the execution ground with a handkerchief, considered her a martyr.

But legends are just legends, and 232 years after Marie Antoinette's death, we should face the circumstances and truth of that time and use it as an opportunity to reflect on ourselves and society through the diverse human figures.

“Tragedy always hides in the folds of what is not seen.”

Professor Joo Myeong-cheol, who translated this book, explains its significance as follows:

How legal and just was Marie Antoinette's trial? What use is it to ask such a question from today's perspective? As in any other era, but even more so during the Reign of Terror, politics superseded law.

The trial of Marie Antoinette is a prime example.

Emmanuel de Baresquiel uses Marie Antoinette as his entrance to lead us into the Revolutionary Court and shows us how the courts functioned at that time.

The atmosphere of the prison and courtroom, made even more gloomy by the lack of light due to the limitations of the time, the psychology of the queen who was dragged there, the sociology of the jury and witnesses, and the mechanisms of the reign of terror were all brought to life through the author's insight and meticulous yet leisurely descriptions.

The reader can feel the dust, sounds, and even smells floating in the darkness as Marie Antoinette moves from the Tower of the Temple to the Conciergerie on August 2, 1793, completes simple formalities, and enters the cell she is assigned to.

(Page 375)

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 19, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 400 pages | 556g | 151*215*19mm

- ISBN13: 9791187700999

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)