Archaeology and the State

|

Description

Book Introduction

Bruce Routledge, professor of archaeology at the University of Liverpool in the UK, explains the formation and functioning of the state from an archaeological perspective.

The state is often thought of as a single entity, but according to Routledge, it is the result of a combination of various elements that form political authority.

Therefore, in order to understand the process of formation and operation of a state, we must examine the process of formation and operation of political authority.

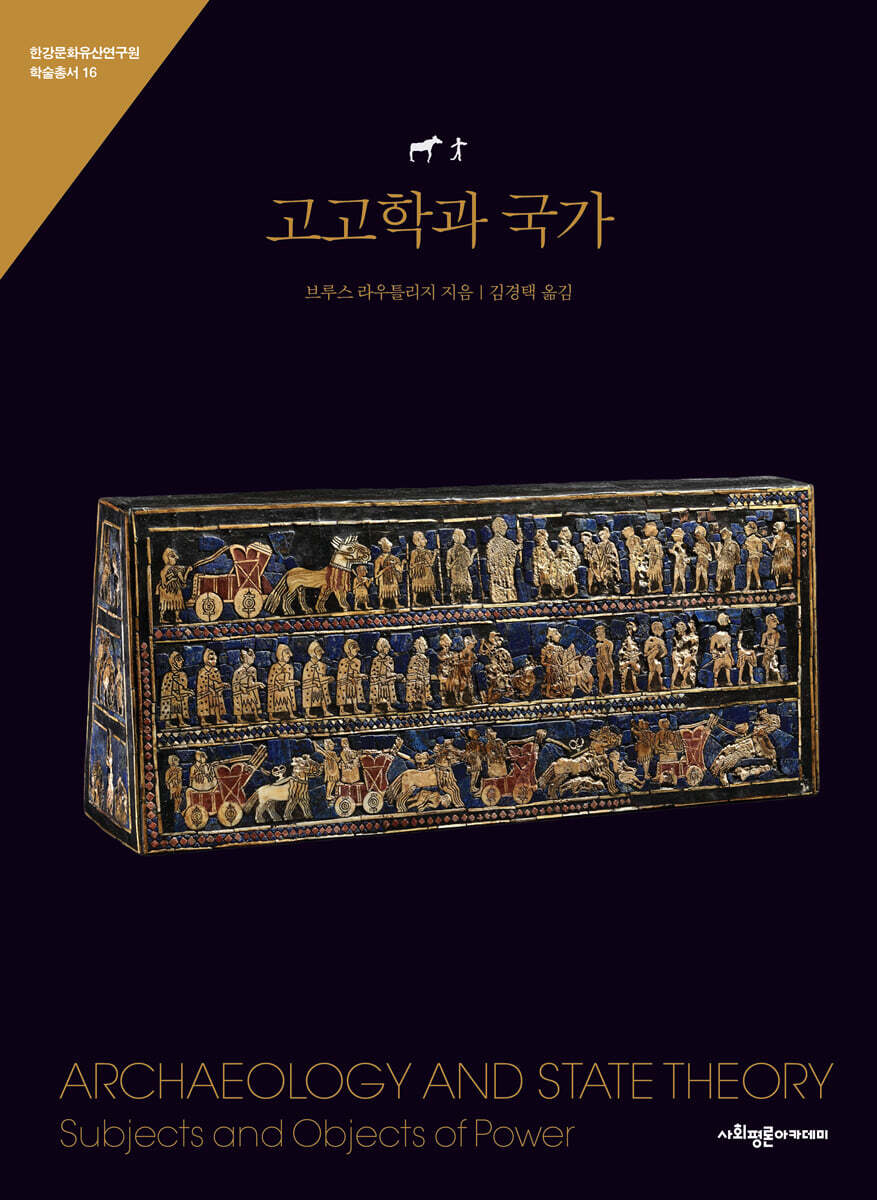

This book examines the ways in which political authority is exercised and the process by which legitimacy is granted to political authority, focusing on Antonio Gramsci's concept of hegemony. It also examines the core elements that constitute political authority by analyzing various archaeological cases, such as the Imerina Kingdom in Madagascar, Athens in ancient Greece, the Inca Empire, the Mayan civilization, and the Royal Tombs of Ur in Mesopotamia.

The state is often thought of as a single entity, but according to Routledge, it is the result of a combination of various elements that form political authority.

Therefore, in order to understand the process of formation and operation of a state, we must examine the process of formation and operation of political authority.

This book examines the ways in which political authority is exercised and the process by which legitimacy is granted to political authority, focusing on Antonio Gramsci's concept of hegemony. It also examines the core elements that constitute political authority by analyzing various archaeological cases, such as the Imerina Kingdom in Madagascar, Athens in ancient Greece, the Inca Empire, the Mayan civilization, and the Royal Tombs of Ur in Mesopotamia.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

List of pictures

Note

Orientation

Chapter 1: (New) Evolution and Beyond

Chapter 2 Coercion and Consent

Chapter 3: The Operation of Hegemony: The Kingdom of Imerina in Madagascar

Chapter 4 Beyond Politics: Athens and the Inca Empire

Chapter 5: Spectacle and Routine

Chapter 6: Everyday Life and Dramatic Death: The Royal Tombs of Ur

Chapter 7 Conclusion: A Dangerous Comparison

Translator's Note

Journal name

References

Search

Note

Orientation

Chapter 1: (New) Evolution and Beyond

Chapter 2 Coercion and Consent

Chapter 3: The Operation of Hegemony: The Kingdom of Imerina in Madagascar

Chapter 4 Beyond Politics: Athens and the Inca Empire

Chapter 5: Spectacle and Routine

Chapter 6: Everyday Life and Dramatic Death: The Royal Tombs of Ur

Chapter 7 Conclusion: A Dangerous Comparison

Translator's Note

Journal name

References

Search

Into the book

Defining the state narrowly in terms of its official functions and institutions ignores the socially embedded nature of state power.

On the other hand, if we define the state broadly as some kind of comprehensive social system, the true limits of state power are ignored.

---From "Orientation"

More urgent than the question of the definition of the state is the ontological question of how the state exists.

While recognizing that the state is not simply or clearly a single entity, how a particular state is explicitly constituted by the practices, discourses, and strategies of particular individuals remains assumed and unaddressed in most critiques of neo-evolutionism.

---From “Chapter 1 (New) Evolution and After”

The coercive power of political society itself must essentially constitute a phase of hegemony.

Here we see how practices and strategies of political authority, coercive power, and transcendental identity intersect and reinforce each other under the umbrella of hegemony as a moral order.

---From “Chapter 2: Coercion and Consent”

The formation of a political body is not a simple process in which one side dominates and the other side revolutionizes.

Rather, the formation of a polity is framed by power relations and involves ongoing debates about what a hegemonic order includes and does not include, taking place in a context where cultural and material resources are unequally distributed among participants.

---From "Chapter 3: The Operation of Hegemony: The Kingdom of Imerina in Madagascar"

The courtyard house was a crucial space in classical Athens that not only embodied the material interdependence of economy, politics, gender, and identity, but also constituted them.

This material interdependence is activated, strengthened, and re-inscribed through the practice of civic hegemony.

---From Chapter 4 Beyond Politics: Athens and the Inca Empire

Ritual performances may be directed to a broad or limited audience, or to the performer himself, a deity, past ancestors, or future descendants.

What is significant is that the spectacle participates in the construction and representation of a particular moral order, and also includes its participants.

---From Chapter 5, Spectacle and Routine

It is not certain whether the attendant buried in the royal tomb was the most subordinate member of the household.

It is also unknown whether they were loyal and honorable volunteers, prisoners of war, paupers, or simply suitable surplus.

The funerary spectacle of the Ur royal tombs shows only that such distinctions are no longer significant.

Regardless of origin, the dying are absorbed into a service role that reproduces the hegemonic order of the institutional household in a ritual drama that fuses authority, violence, and transcendence with the power of governance.

---From "Chapter 6: Everyday Life and Dramatic Death: The Royal Tombs of Ur"

In response to this, it is important to emphasize the position of violence and hegemony in my argument.

The cases analyzed in this book are defined by violence.

In other words, violence is not a characteristic of other phenomena such as the state.

Rather, this book is about sovereignty, a form of institutional violence.

On the other hand, if we define the state broadly as some kind of comprehensive social system, the true limits of state power are ignored.

---From "Orientation"

More urgent than the question of the definition of the state is the ontological question of how the state exists.

While recognizing that the state is not simply or clearly a single entity, how a particular state is explicitly constituted by the practices, discourses, and strategies of particular individuals remains assumed and unaddressed in most critiques of neo-evolutionism.

---From “Chapter 1 (New) Evolution and After”

The coercive power of political society itself must essentially constitute a phase of hegemony.

Here we see how practices and strategies of political authority, coercive power, and transcendental identity intersect and reinforce each other under the umbrella of hegemony as a moral order.

---From “Chapter 2: Coercion and Consent”

The formation of a political body is not a simple process in which one side dominates and the other side revolutionizes.

Rather, the formation of a polity is framed by power relations and involves ongoing debates about what a hegemonic order includes and does not include, taking place in a context where cultural and material resources are unequally distributed among participants.

---From "Chapter 3: The Operation of Hegemony: The Kingdom of Imerina in Madagascar"

The courtyard house was a crucial space in classical Athens that not only embodied the material interdependence of economy, politics, gender, and identity, but also constituted them.

This material interdependence is activated, strengthened, and re-inscribed through the practice of civic hegemony.

---From Chapter 4 Beyond Politics: Athens and the Inca Empire

Ritual performances may be directed to a broad or limited audience, or to the performer himself, a deity, past ancestors, or future descendants.

What is significant is that the spectacle participates in the construction and representation of a particular moral order, and also includes its participants.

---From Chapter 5, Spectacle and Routine

It is not certain whether the attendant buried in the royal tomb was the most subordinate member of the household.

It is also unknown whether they were loyal and honorable volunteers, prisoners of war, paupers, or simply suitable surplus.

The funerary spectacle of the Ur royal tombs shows only that such distinctions are no longer significant.

Regardless of origin, the dying are absorbed into a service role that reproduces the hegemonic order of the institutional household in a ritual drama that fuses authority, violence, and transcendence with the power of governance.

---From "Chapter 6: Everyday Life and Dramatic Death: The Royal Tombs of Ur"

In response to this, it is important to emphasize the position of violence and hegemony in my argument.

The cases analyzed in this book are defined by violence.

In other words, violence is not a characteristic of other phenomena such as the state.

Rather, this book is about sovereignty, a form of institutional violence.

---From "Chapter 7 Conclusion: Dangerous Comparisons"

Publisher's Review

What is a nation?

― A nation revisited through the lens of archaeology

When we think of a particular country, we usually think of its name, territory, or people who live there.

When we think of a nation in this way, the object that comes to mind is a specific and single entity.

But is a large-scale political community like a nation truly composed of a single entity? Bruce Routledge, the author of this book, points out that existing research tends to assume the nation is a single, fixed entity.

However, the state is not a single entity, but rather the result of the formation of political authority, that is, power.

Therefore, in order to understand the process of formation and operation of a state, we must examine the process of formation and operation of political authority.

How is power created?

― Reproduction of authority through tradition, practice, and ritual

The author examines the ways in which political authority is formed and exercised, and the process by which legitimacy is granted to that power, focusing on political philosopher Antonio Gramsci's concept of hegemony. He then uses archaeological research to explore how the form of the state was formed in various political systems throughout history and how the authority of rulers was established.

The process of forming and maintaining state power is clearly revealed in various archaeological cases, such as the Imerina Kingdom in Madagascar, Athens in ancient Greece, the Inca, the Maya, and Mesopotamia.

For example, in the 19th-century Kingdom of Imerina in Madagascar, traditions were used to strengthen royal authority, while in ancient Athens and the Inca Empire, political power was shaped by material and cultural practices.

In the Mayan civilization, authority was recreated through 'spectacular' events and everyday rituals, and in Ur in Mesopotamia, ruling power was consolidated through funeral rites.

In this way, in ancient countries, authority was reproduced through traditions, practices, and rituals, and these were used as a means of maintaining the ruler's system.

Drawing on examples from various periods and regions, this book helps us understand the nation not as a single entity but as a product of relationships and practices.

Following the author's analysis will broaden your perspective on the nation and allow you to reexamine existing common sense.

I hope that this book, where archaeology and political theory meet, will deepen our discussion of the state.

― A nation revisited through the lens of archaeology

When we think of a particular country, we usually think of its name, territory, or people who live there.

When we think of a nation in this way, the object that comes to mind is a specific and single entity.

But is a large-scale political community like a nation truly composed of a single entity? Bruce Routledge, the author of this book, points out that existing research tends to assume the nation is a single, fixed entity.

However, the state is not a single entity, but rather the result of the formation of political authority, that is, power.

Therefore, in order to understand the process of formation and operation of a state, we must examine the process of formation and operation of political authority.

How is power created?

― Reproduction of authority through tradition, practice, and ritual

The author examines the ways in which political authority is formed and exercised, and the process by which legitimacy is granted to that power, focusing on political philosopher Antonio Gramsci's concept of hegemony. He then uses archaeological research to explore how the form of the state was formed in various political systems throughout history and how the authority of rulers was established.

The process of forming and maintaining state power is clearly revealed in various archaeological cases, such as the Imerina Kingdom in Madagascar, Athens in ancient Greece, the Inca, the Maya, and Mesopotamia.

For example, in the 19th-century Kingdom of Imerina in Madagascar, traditions were used to strengthen royal authority, while in ancient Athens and the Inca Empire, political power was shaped by material and cultural practices.

In the Mayan civilization, authority was recreated through 'spectacular' events and everyday rituals, and in Ur in Mesopotamia, ruling power was consolidated through funeral rites.

In this way, in ancient countries, authority was reproduced through traditions, practices, and rituals, and these were used as a means of maintaining the ruler's system.

Drawing on examples from various periods and regions, this book helps us understand the nation not as a single entity but as a product of relationships and practices.

Following the author's analysis will broaden your perspective on the nation and allow you to reexamine existing common sense.

I hope that this book, where archaeology and political theory meet, will deepen our discussion of the state.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: February 25, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 222 pages | 188*257*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791167071750

- ISBN10: 1167071751

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)