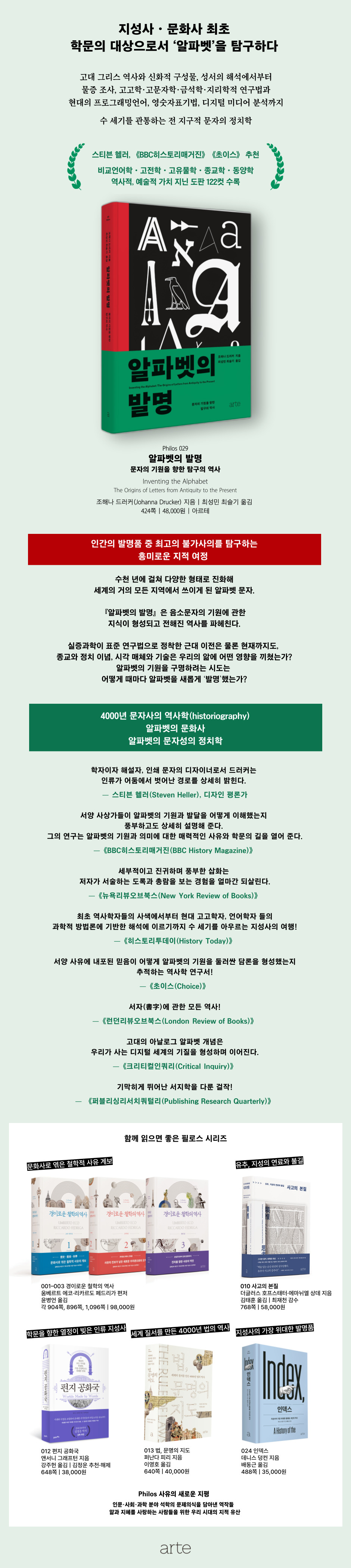

Invention of the alphabet

|

Description

Book Introduction

The first in intellectual and cultural history

Exploring the 'alphabet' as an object of study

From ancient Greek history and mythological constructs to interpretations of the Bible,

Evidence investigation, archaeological, paleographic, epigraphic, and geographical research methods

From modern programming languages to alphanumeric notation and digital media analysis.

The Politics of Global Writing Through the Centuries

★ Comparative linguistics, classics, paleontology, religious studies, oriental studies… …

Includes 122 illustrations of historical and artistic value.

Joanna Drucker (Professor of Library and Information Science at UCLA), who has led experimental and in-depth projects in the fields of books and print culture, visual arts, and contemporary art, is a world-renowned historian who has studied the history of letters and experimental typography for over 40 years.

Drucker's work is widely cited by digital humanities researchers, artists, and cultural critics around the world, and has contributed significantly to the popular understanding of the cultural and social role of visual communication.

Joanna Drucker, an authority in aesthetics and digital humanities, has condensed the results of her 40 years of research into Inventing the Alphabet: The Origins of Letters from Antiquity to the Present (Philos Series No. 29).

This book traces the origins and development of the alphabet through archaeological, paleographic, epigraphic, and geographical approaches. It supports the former research by exploring the visual forms of language from an aesthetic perspective, and extends the analysis to modern language systems (programming languages, Unicode, alphanumeric notation) through a digital humanities approach.

In this book, the author takes two unique perspectives as an 'art researcher' and an 'artist'.

First, as an art researcher, I seek to unify numerous major debates within mainstream academia and, by systematizing and interpreting scattered and difficult literature with material evidence, to counter the exclusivity and uniformity of texts that the West has traditionally embraced, I trace evidence of pluralism, hybridity, and inclusiveness.

This is done through rigorous scientific research methods, and also dispels the myth of the “genesis” or “discovery” of the alphabet.

Second, as an artist, I focus my research on the aspects of ‘historiography of the history of letters’ and ‘political and intellectual history related to the history of the alphabet’, and ask the following questions.

“Who discovered ‘what’, ‘when’, and ‘how’ about the alphabet?” “How did the way this knowledge was acquired—through writing, pictures, inscriptions, or artifacts—influence our ‘recognition’ of the identity and origin of the alphabet’s letters?” The author’s metacognitive approach serves as a mechanism for granting the study of the history of writing its status as “a fertile field for inspiration for artists and mystical contemplation.”

From the above two perspectives, the author derives the following proposition.

“The alphabet was not discovered, but invented through a form of knowledge production that takes the alphabet as its object.” The author takes a broad view of the literature (the works of archaeologists, paleographers, epigraphers, classicists, comparative linguists, historical linguists, religious scholars, biblical scholars, orientalists, Semitic linguists, runeologists, Masoretic scribes, and researchers of antiquities) that is full of heated debates and conflicting points of view, and presents 122 rare illustrations of high academic value, opening up an attractive path of thought for the readers.

Furthermore, by examining the blind spots and biases of each researcher, we establish the historical value and political status of the alphabet from its current position.

The reason the author's research is important is because it provides insight into humanity's 'way of thinking' and 'way of communicating.'

This study is directly connected to the study of ‘Western history of thought’ and ‘intellectual history’.

Exploring the 'alphabet' as an object of study

From ancient Greek history and mythological constructs to interpretations of the Bible,

Evidence investigation, archaeological, paleographic, epigraphic, and geographical research methods

From modern programming languages to alphanumeric notation and digital media analysis.

The Politics of Global Writing Through the Centuries

★ Comparative linguistics, classics, paleontology, religious studies, oriental studies… …

Includes 122 illustrations of historical and artistic value.

Joanna Drucker (Professor of Library and Information Science at UCLA), who has led experimental and in-depth projects in the fields of books and print culture, visual arts, and contemporary art, is a world-renowned historian who has studied the history of letters and experimental typography for over 40 years.

Drucker's work is widely cited by digital humanities researchers, artists, and cultural critics around the world, and has contributed significantly to the popular understanding of the cultural and social role of visual communication.

Joanna Drucker, an authority in aesthetics and digital humanities, has condensed the results of her 40 years of research into Inventing the Alphabet: The Origins of Letters from Antiquity to the Present (Philos Series No. 29).

This book traces the origins and development of the alphabet through archaeological, paleographic, epigraphic, and geographical approaches. It supports the former research by exploring the visual forms of language from an aesthetic perspective, and extends the analysis to modern language systems (programming languages, Unicode, alphanumeric notation) through a digital humanities approach.

In this book, the author takes two unique perspectives as an 'art researcher' and an 'artist'.

First, as an art researcher, I seek to unify numerous major debates within mainstream academia and, by systematizing and interpreting scattered and difficult literature with material evidence, to counter the exclusivity and uniformity of texts that the West has traditionally embraced, I trace evidence of pluralism, hybridity, and inclusiveness.

This is done through rigorous scientific research methods, and also dispels the myth of the “genesis” or “discovery” of the alphabet.

Second, as an artist, I focus my research on the aspects of ‘historiography of the history of letters’ and ‘political and intellectual history related to the history of the alphabet’, and ask the following questions.

“Who discovered ‘what’, ‘when’, and ‘how’ about the alphabet?” “How did the way this knowledge was acquired—through writing, pictures, inscriptions, or artifacts—influence our ‘recognition’ of the identity and origin of the alphabet’s letters?” The author’s metacognitive approach serves as a mechanism for granting the study of the history of writing its status as “a fertile field for inspiration for artists and mystical contemplation.”

From the above two perspectives, the author derives the following proposition.

“The alphabet was not discovered, but invented through a form of knowledge production that takes the alphabet as its object.” The author takes a broad view of the literature (the works of archaeologists, paleographers, epigraphers, classicists, comparative linguists, historical linguists, religious scholars, biblical scholars, orientalists, Semitic linguists, runeologists, Masoretic scribes, and researchers of antiquities) that is full of heated debates and conflicting points of view, and presents 122 rare illustrations of high academic value, opening up an attractive path of thought for the readers.

Furthermore, by examining the blind spots and biases of each researcher, we establish the historical value and political status of the alphabet from its current position.

The reason the author's research is important is because it provides insight into humanity's 'way of thinking' and 'way of communicating.'

This study is directly connected to the study of ‘Western history of thought’ and ‘intellectual history’.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface 7

1 When did the alphabet become the 'Greek alphabet'? - 15

2 A Gift from God—The Original Writings, Moses, and the Sinai Tablets 49

3 Medieval Lions—Magic Alphabet, Mythological Characters, and Exotic Alphabet 75

4 Language Confusion and Character Encyclopedia 111

5. Explanation of Unique Objects: The Origin and Development of Writing 149

Harmony of the 6 Tables and the Alphabet 185

7 Modern Archaeology—Reflecting the Alphabetical Evidence 223

8 Interpreting the Early Alphabet—Epigraphy and Paleolithics 267

9 Alphabetic Effects and the Politics of Letters 315

The Power of the Alphabet and Global Hegemony 347

Week 361

Reference 389

Translator's Note 401

Search 407

1 When did the alphabet become the 'Greek alphabet'? - 15

2 A Gift from God—The Original Writings, Moses, and the Sinai Tablets 49

3 Medieval Lions—Magic Alphabet, Mythological Characters, and Exotic Alphabet 75

4 Language Confusion and Character Encyclopedia 111

5. Explanation of Unique Objects: The Origin and Development of Writing 149

Harmony of the 6 Tables and the Alphabet 185

7 Modern Archaeology—Reflecting the Alphabetical Evidence 223

8 Interpreting the Early Alphabet—Epigraphy and Paleolithics 267

9 Alphabetic Effects and the Politics of Letters 315

The Power of the Alphabet and Global Hegemony 347

Week 361

Reference 389

Translator's Note 401

Search 407

Detailed image

Into the book

“Since ancient Greece, all peoples of the Western cultural sphere have been descendants of alphabetic writing.” This sentence, from a 2016 article by Lawrence de Rouge, perpetuates the persistent myth that the Western alphabet was invented in Greece.

This misconception appeared late in the 2,500-year history of alphabetic science.

Most scholars were convinced that Herodotus' writings were accurate.

Besides this, classical authors made it clear that the Greeks were well aware that, like many other knowledge and skills, they had borrowed the alphabet from other cultures.

Until the 17th century, history relied largely on information available in literature.

Herodotus and Plato were important because they recorded early testimony that served as a basis for confirming new evidence.

Even if Herodotus had only given names to the letters—and thus made them objects of interest and study—his contribution would have been considerable.

---From "Chapter 1: When Did the Alphabet Become 'Greek Letters'?"

Interest in biblical sources remains strong, travelogues broaden primary knowledge and records of inscriptions, and accumulating evidence, combined with ongoing research, expands the details that form the basis for developing historical arguments.

No one has ever addressed the logical question of how Moses could have read the Torah if he could not write or knew the alphabet.

However, from ancient times to the modern era, historians have moved away from a literal reading of biblical passages and toward a rational interpretation.

Their elaborate genealogy of citations gradually receded as other means of disseminating knowledge emerged.

Another means of transmission, the graphic lion, also helped preserve mythological traditions and imbue texts with magical powers.

---From "Chapter 2: A Gift from God - The Original Writings, Moses, and the Sinai Stone Tablets"

The lion tradition adds a visual dimension to alphabetology.

In classical literature and the Bible, alphabetic characters are mentioned but not shown.

The Greeks viewed the alphabet as a writing system spread through cultural exchange, while in the Biblical and Kabbalistic traditions, the alphabet was seen as a gift from God, possessing the power to create the world.

However, the transmission through graphics reveals the recognition that the alphabet is formed in a specific visual form, and that this form has a potential for symbolic power or historical identity.

Among the characters that have been passed down since ancient times, there were not only actual alphabets used for writing documents, but also magical, mythical, and exotic alphabets that were copied from legends that were never used for writing.

---From "Chapter 3: The Life of the Middle Ages - Magic Alphabet, Mythical Characters, and Exotic Alphabet"

In the early 16th century, when encyclopedias became popular, printed books containing alphabetic character specimens appeared one after another.

There were various factors behind this.

These include the urge to collect occult or mystical knowledge, the curiosity about exotic and ancient scripts, and the desire to have an encyclopedic grasp of vast historical and regional information.

As linguistic diversity was analyzed as evidence supporting the linguistic confusion of the Tower of Babel, which was considered a historical fact, the search for humanity's 'original' alphabet also continued.

---From "Chapter 4: Language Confusion and a Compendium of Characters"

From the 17th to the 18th centuries, the main source of information about the origins of the alphabet was literary sources.

… … As interest in the gradual change in letter form, or ‘the progress of letters’, grew, efforts to find the ‘origins’ of the alphabet also continued.

Although documentary research was not completely abandoned, it was no longer considered sufficient, and techniques borrowed from the natural sciences began to support historical analysis.

This was the background to the formation of a new historical view that a complete and unchanging 'true' alphabet was not created all at once, but developed over time.

This research was supported by the restoration of 'antiques' such as coins, statues, ceramics, and monuments collected in the curio room and private collections, or by inscriptions found on site and published in luxurious books.

---From "Chapter 5: Explanation of Unique Objects - Origin and Development of Letters"

Graphic diagrams have become an important tool for formulating and presenting arguments about the origin and development of the alphabet.

The basic grid format of rows and columns has a long history in this field of study—longer in other fields.

This format effectively convinces the reader of connections through a structure that assumes similarities between symbols that are taken from context and presented in a certain size, proportion, and order.

Such rational methods may be used for fanciful purposes, but this is true of any form of knowledge production.

Even rigorous fields like paleography and archaeology can be subject to outlandish claims.

Even when these fields are used to broaden understanding,

Our current knowledge of the origins and development of the alphabet is based on such research.

---From "Harmony of the 6th Chapter's Table of Rhetoric and the Alphabet"

Thanks to archaeological research and discoveries, the concept of the alphabet has been transformed into a historical entity born of dispersed geographical and cultural exchanges.

The alphabet is now considered not to be a given, but rather something created by humans in a specific cultural environment located in a specific geographical location and era.

Old concepts don't disappear, and paradigms lose their power only slowly.

Throughout the 19th century, scholars deeply preoccupied with the Old Testament continued to interpret archaeological evidence within that framework, and they still do today.

It seems easier to shape evidence to fit one's beliefs than to change them based on evidence.

---From "Chapter 7 Modern Archaeology - Putting Alphabet-Related Evidence in Its Place"

As a historical entity, the 'alphabet' is constantly interpreted through a frame of reference that sometimes guides the narrative to fit the artifacts and sometimes fits the evidence to the narrative.

And the politics of alphabetic history remains a lingering feature of a field where every discovery and piece of evidence carries emotional weight.

---From "Chapter 8 Interpreting the Early Alphabet - Epigraphy and Paleolithics"

Postcolonial theory and cultural studies on letters, literacy, and writing have sparked sharp discussions about the racial prejudices and cultural biases that form part of alphabet studies.

Critical engagement with digital media also provides an opportunity to rethink the very identity of the alphabet as a form of code.

The problems of hegemony and cultural imperialism, whether explicit or implicit, still remain in the operation of alphanumeric notation in digital media and World Wide Web programming languages.

---From "Chapter 9: Alphabet Effects and the Politics of Letters"

The alphabet has become one of the most important innovations in human history, thanks to its widespread adoption across geographies and eras.

However, the alphabet is also fatally linked to the forces of colonization and normalization.

Literacy is an indispensable means not only of liberation but also of power—and of its abuse.

The alphabet is a way of organizing information and knowledge according to a standard that is so natural that the very assumption has disappeared.

However, durability and versatility are also prominent features of the alphabet's identity.

This misconception appeared late in the 2,500-year history of alphabetic science.

Most scholars were convinced that Herodotus' writings were accurate.

Besides this, classical authors made it clear that the Greeks were well aware that, like many other knowledge and skills, they had borrowed the alphabet from other cultures.

Until the 17th century, history relied largely on information available in literature.

Herodotus and Plato were important because they recorded early testimony that served as a basis for confirming new evidence.

Even if Herodotus had only given names to the letters—and thus made them objects of interest and study—his contribution would have been considerable.

---From "Chapter 1: When Did the Alphabet Become 'Greek Letters'?"

Interest in biblical sources remains strong, travelogues broaden primary knowledge and records of inscriptions, and accumulating evidence, combined with ongoing research, expands the details that form the basis for developing historical arguments.

No one has ever addressed the logical question of how Moses could have read the Torah if he could not write or knew the alphabet.

However, from ancient times to the modern era, historians have moved away from a literal reading of biblical passages and toward a rational interpretation.

Their elaborate genealogy of citations gradually receded as other means of disseminating knowledge emerged.

Another means of transmission, the graphic lion, also helped preserve mythological traditions and imbue texts with magical powers.

---From "Chapter 2: A Gift from God - The Original Writings, Moses, and the Sinai Stone Tablets"

The lion tradition adds a visual dimension to alphabetology.

In classical literature and the Bible, alphabetic characters are mentioned but not shown.

The Greeks viewed the alphabet as a writing system spread through cultural exchange, while in the Biblical and Kabbalistic traditions, the alphabet was seen as a gift from God, possessing the power to create the world.

However, the transmission through graphics reveals the recognition that the alphabet is formed in a specific visual form, and that this form has a potential for symbolic power or historical identity.

Among the characters that have been passed down since ancient times, there were not only actual alphabets used for writing documents, but also magical, mythical, and exotic alphabets that were copied from legends that were never used for writing.

---From "Chapter 3: The Life of the Middle Ages - Magic Alphabet, Mythical Characters, and Exotic Alphabet"

In the early 16th century, when encyclopedias became popular, printed books containing alphabetic character specimens appeared one after another.

There were various factors behind this.

These include the urge to collect occult or mystical knowledge, the curiosity about exotic and ancient scripts, and the desire to have an encyclopedic grasp of vast historical and regional information.

As linguistic diversity was analyzed as evidence supporting the linguistic confusion of the Tower of Babel, which was considered a historical fact, the search for humanity's 'original' alphabet also continued.

---From "Chapter 4: Language Confusion and a Compendium of Characters"

From the 17th to the 18th centuries, the main source of information about the origins of the alphabet was literary sources.

… … As interest in the gradual change in letter form, or ‘the progress of letters’, grew, efforts to find the ‘origins’ of the alphabet also continued.

Although documentary research was not completely abandoned, it was no longer considered sufficient, and techniques borrowed from the natural sciences began to support historical analysis.

This was the background to the formation of a new historical view that a complete and unchanging 'true' alphabet was not created all at once, but developed over time.

This research was supported by the restoration of 'antiques' such as coins, statues, ceramics, and monuments collected in the curio room and private collections, or by inscriptions found on site and published in luxurious books.

---From "Chapter 5: Explanation of Unique Objects - Origin and Development of Letters"

Graphic diagrams have become an important tool for formulating and presenting arguments about the origin and development of the alphabet.

The basic grid format of rows and columns has a long history in this field of study—longer in other fields.

This format effectively convinces the reader of connections through a structure that assumes similarities between symbols that are taken from context and presented in a certain size, proportion, and order.

Such rational methods may be used for fanciful purposes, but this is true of any form of knowledge production.

Even rigorous fields like paleography and archaeology can be subject to outlandish claims.

Even when these fields are used to broaden understanding,

Our current knowledge of the origins and development of the alphabet is based on such research.

---From "Harmony of the 6th Chapter's Table of Rhetoric and the Alphabet"

Thanks to archaeological research and discoveries, the concept of the alphabet has been transformed into a historical entity born of dispersed geographical and cultural exchanges.

The alphabet is now considered not to be a given, but rather something created by humans in a specific cultural environment located in a specific geographical location and era.

Old concepts don't disappear, and paradigms lose their power only slowly.

Throughout the 19th century, scholars deeply preoccupied with the Old Testament continued to interpret archaeological evidence within that framework, and they still do today.

It seems easier to shape evidence to fit one's beliefs than to change them based on evidence.

---From "Chapter 7 Modern Archaeology - Putting Alphabet-Related Evidence in Its Place"

As a historical entity, the 'alphabet' is constantly interpreted through a frame of reference that sometimes guides the narrative to fit the artifacts and sometimes fits the evidence to the narrative.

And the politics of alphabetic history remains a lingering feature of a field where every discovery and piece of evidence carries emotional weight.

---From "Chapter 8 Interpreting the Early Alphabet - Epigraphy and Paleolithics"

Postcolonial theory and cultural studies on letters, literacy, and writing have sparked sharp discussions about the racial prejudices and cultural biases that form part of alphabet studies.

Critical engagement with digital media also provides an opportunity to rethink the very identity of the alphabet as a form of code.

The problems of hegemony and cultural imperialism, whether explicit or implicit, still remain in the operation of alphanumeric notation in digital media and World Wide Web programming languages.

---From "Chapter 9: Alphabet Effects and the Politics of Letters"

The alphabet has become one of the most important innovations in human history, thanks to its widespread adoption across geographies and eras.

However, the alphabet is also fatally linked to the forces of colonization and normalization.

Literacy is an indispensable means not only of liberation but also of power—and of its abuse.

The alphabet is a way of organizing information and knowledge according to a standard that is so natural that the very assumption has disappeared.

However, durability and versatility are also prominent features of the alphabet's identity.

---From "The Power of the Alphabet and Global Hegemony"

Publisher's Review

The history of 4000 years of writing

― When and where did letters appear?

"The Invention of the Alphabet" provides the first intellectual and cultural account of the "origin and development of the alphabet over 4,000 years."

This book covers 2,500 years of history, starting with Herodotus (around 440 BC), who first historically mentioned the alphabet, and explains the circumstances in Chapter 1, "When Did the Alphabet Become 'Greek Letters'?"

The author points out that from the Linear A of the Minoan civilization in the early 2nd millennium BC, which is the earliest form of writing, and the Linear B derived from it around 1600 BC (Chapter 1, pp. 18-19), to the Linear Phoenician script, a relatively standardized alphabetic script in the late 2nd millennium BC, when the alphabet essentially influenced knowledge production as a whole, it functioned as part of the culture of coastal cities such as Tyre, Byblos, and Sidon (Chapter 7, “Modern Archaeology,” pp. 223-224), in other words, this book covers the global history of writing that spans 4,000 years.

While the history of the alphabet has been studied quite accurately, little is known about the historiography of the alphabet.

Among the 4,000 years of history of writing, the author fundamentally deals with the 'history of the alphabet.'

It has the character of a literature study that traces the 'lineage of transmission', 'writing', and 'the citation that established the 'concept' of the alphabet.

This is also a very important and fascinating case study in relation to the history of Western thought.

Because it provides insight into how the physical properties of knowledge production and dissemination give rise to intellectual concepts.

The Cultural History of the Alphabet, the Politics of Alphabetic Literacy

How the Alphabet Spread Around the World

― How did it come to support global communication?

The author approaches archaeological research to establish a genealogy of objects in relation to their historical past.

Because “the nature of the evidence shapes historical claims.”

It combines knowledge of the 'cultural history of the alphabet' in that it explains in detail how the alphabet was formed and developed in the culture of each era, from the early writing systems of ancient times (Mycenaean and Minoan civilizations, the ancient city of Thebes, classical Greece, etc.) to the alphabet we use today.

The author expands the discussion to explore the ‘politics of alphabetic literacy’ in that the invention of the alphabet goes beyond the influence on mankind’s ‘way of thinking’ and ‘way of communication’ to the neurological and physiological effects of the alphabet (“Gene-Culture Coevolution Theory”, Robert Logan, Derek de Kerkhove, Ivan Illich’s study, pp. 334-335) and even reaches the point of defining other cultures by ‘gendering’ them (Leonard Silane’s Analysis of the Alphabet of Ancient Cultures, pp. 342-343).

“In today’s academic world, where decolonization of knowledge is a familiar topic of academic conversation, it is no longer acceptable to think of the alphabet as a neutral technology.

Clearly, the alphabet itself is a complex cultural system, and its dynamics are partly instrumental, partly accidental, and sometimes intentional, producing positive or negative effects.

Standards laws become part of an asymmetrical political structure in which those who set standards have more power than those who follow them.

Literacy, in whatever form it takes, both grants and deprives rights.

… … The role and historical position of the alphabet in producing and disseminating knowledge and imagination cannot be erased without damaging a significant part of our humanity.” (Page 348, note “The Power of the Alphabet and Global Hegemony”)

A fascinating intellectual journey exploring the greatest wonders of human invention.

― From Plato's imagination, Kabbalah, occult knowledge systems, and mystical writings to modern research methods

The author cites and studies numerous historical sources to establish the following fact: “All alphabetic characters originated from the same proto-Semitic script, which spread across Europe, Arabia, Africa, and Southeast Asia, and as a result, visually diversified into Greek, Cyrillic, Tamil, Burmese, Balinese, Roman, and Thai scripts,” and points out the beliefs that have corresponded to each period and intellectual framework.

We also do not overlook the fact that the process by which misunderstandings are formed is part of the long history of knowledge production and dissemination.

In early accounts of the history of the alphabet, the alphabet was considered a 'birth' or a 'gift from God', and for as long as 2,000 years, the alphabet was associated with cosmology and given a semi-divine status in spiritual or religious belief systems.

The origins of the alphabet are a fascinating mixture of myth and partial fact, as evidenced by the extensive literature, including attributions of the alphabet to “the finger of God, to the writing of the stars, to the wandering Jews of the Sinai Peninsula, to the Egyptian god Thoth (Theut), and to the Phoenicians.”

As in the previous examples, the historical knowledge that elucidated the origins of the alphabet was formed based on evidence known at the time and beliefs combined with that evidence, and this became an intellectual heritage that contributed to the establishment of the current orthodoxy.

Plato argued that writing was invented in Egypt, attributing its origin to the work of the Egyptian god Thoth, and introduced a more multifaceted concept of language development (p. 26).

Although not as Plato imagined, Egypt's contribution cannot be denied as having influenced the current orthodoxy.

The desire to imbue the letters of the alphabet with divine powers is central to Kabbalistic thought (Baron van Helmont's Studies, p. 59).

The author notes that these belief systems sought to recognize and explore the "profound power of the alphabet as a driving force."

This was a characteristic shared by other mystical traditions of the Hellenistic world, such as Gnosticism and Pythagorean symbolism, which linked Greek concepts of letters to complex cosmic order. (p. 76, Chapter 3, “The Life of the Lion in the Middle Ages”)

Alphabet also played an important role in occult knowledge systems (cryptography, magical writing, the symbolic system derived from ancient Hermeticism, a field that Trithemius was fascinated by) and mystical writings (Hebrew script with celestial developments, and river crossing writing). However, the author notes that the practice of mixing mythological and existential writings, as seen in the works of William Hurey and Athanasius Kircher, disappeared with the introduction of new contextual visual information (tables) presented in their publications. (p. 200, Chapter 6, “The Harmony of Table Rhetoric and the Alphabet”)

With the introduction of these visual information, the 'celestial characters' and 'magic alphabets' outside of occult and esoteric literature disappeared, and the differences in research methods between the 16th and 17th centuries (incomplete character table form) and the 18th century (a time when the table form of a rational comparative research method, a time when linguistic research became more sophisticated) are pointed out.

The author argues that epigraphic methods were in place at this juncture (p. 269, Chapter 8, "Interpreting the Early Alphabet").

It is revealed that the rich material value of Greco-Latin inscriptions, which were the result of the “curiosity of intrepid travelers who traveled to foreign lands to read and decipher the inscriptions on ancient artifacts such as ruins, rocks, and monuments,” was not systematized as a “study of form and type” until the 17th century.

Epigraphy is a field that emerged in earnest in the 18th and 19th centuries thanks to archaeological discoveries, and was praised by Frank Moore Cross in the 20th century for its fundamental importance of having an “eye for form.”

The study of texts requires knowledge of history, biblical archaeology, and linguistics, but it is only possible if epigraphy (or paleography) forms the foundation.

This suggests that regional research based on a “systematized character type classification” is possible and that history can be concretized.

This was related to nationalism.

The idea that each people had unique roots, and that they invented their own unique writing system or language to match their cultural identity, was an academic fad in the 18th century.

LD

Nelm's 『An Attempt to Study the Origin and Elements of Language and Writing』 is a representative work that supports this.

(Pages 180-181, Chapter 5, “Commentary on Antiquities”)

Alphabet's Power, Global Hegemony

From modern empirical scientific research methods to modern understanding

In summary, this book details, along with fascinating historical facts, the lesser-known scholars who contributed to our "modern understanding" of the history of the alphabet.

Among the researchers mentioned by the author, the main figures are as follows:

Hrabanus Maurus (defending the Ister alphabet), Johannes Trithemius (publishing the first major compendium of printed texts, Polygraphia), Teseo Ambrogio (author of appendices to the various languages in the Compendium of the Chaldean Language), Angelo Rocca (form-oriented arrangement of letters using specimen tables and graphic legends), Thomas Astle (dismissing the creation myths of letters, emphasizing the interconnectedness of Phoenician, Hebrew, and Samaritan scripts in The Origin and Development of Writing), Edmund Fry (publishing Universal Writing, a comprehensive and eclectic collection of letters), Charles Foster (comprising a comprehensive tabular compendium of biblical and rational perspectives on the origin of the alphabet), Isaac Taylor (presenting evidence showing the origin and development of the alphabet), Frank Moore Cross (analyzing the development of the alphabetic scripts that contributed to the formation of the alphabet), Joseph Nabe (compares Greek inscriptions with the various stages of alphabetic development), René Derolles (the study of the runic alphabet). Genealogy, a specialty of scholarly tradition), Benjamin Seth (an epigraphist who created tables with aesthetic properties linked to the empirical approach in The Birth and Development of the Alphabet), and Villemain Waal (who synthesized archaeological, epigraphic, and linguistic evidence to date the spread of writing).

Johana Drucker begins with a key passage in Book V of Herodotus's Histories ("Are writing a gift from Cadmus and the Phoenicians?") and traces the Old Testament's record ("Are writing a gift from God to Moses?") to trace the major debates leading up to the modern era, when empirical science became the standard research method, and arrives at a contemporary concept.

It emphasizes that the codes handed down since ancient times are integrated into the global system of computer media and digital communication networks, and that they are closely related to alphanumeric notation at the level just above binary codes made up of mechanical digits and bits.

This persistent system of alphabetic symbols “exerts its power in the global network of the contemporary world, even in non-alphabetic languages.”

The alphabet is analyzed as a method of organizing information and knowledge according to today's standards, and the identity of the alphabet's letters is characterized by 'endurance' and 'versatility'.

In a communications environment interconnected by a global network, the alphabet, by virtue of its reliance on standards, becomes an essential element of a vast hegemonic system that injects Western bias into various levels of infrastructure.

That is, this instrumental dynamic clearly reveals the politics of alphabetic literacy in contemporary life.

To discuss this active motivation, the author cites a unique perspective based on the animist theory of Luther Marsh.

In his closing remarks, in which he declared that he did not believe evolution would end with humans, he praised the endless possibilities of letter combinations, saying, “What was our XYZ in the long alphabet of life has now become our ABC,” and was optimistic that “there is no combination that cannot be readily taken, no action that cannot be performed.”

Regarding this, Jo Hae-na Drucker states that it is an original and unique insight, but it hits the nail on the head.

This is a poignant portrayal of the dynamics of modern writing.

With the advent of computers, a new frame of reference emerged for understanding the fundamental definition of the alphabet, a set of symbols that now form the basis of digital systems that enable the exchange of encoded information.

The author's discussion outlines aspects of the visual identity of characters, their nature as open sets (as reflected in the work of Douglas Hofstadter), and the identity of Unicode (as a digital character code), and addresses aspects of the shifting paradigm of human knowledge.

He emphasizes that “we are still inventing the alphabet.”

This is precisely why this book has monumental value.

The author's research, which seeks to elucidate the history of the alphabet, reminds us of the significance of how the alphabet was 'invented' anew over time, and integrates research on 'Western history of thought,' 'intellectual history,' 'cultural history,' 'politics of literacy,' and 'digital humanities.'

Translator's Note (excerpts)

― Choi Seong-min (Professor of Visual Design, Seoul Metropolitan University), Choi Seul-gi (Professor of Visual Design, Kyewon University of Art and Design)

… … Published 27 years after the publication of 『The Labyrinth of the Alphabet』, 『The Invention of the Alphabet』 shares the commonality of dealing with the history of the alphabet, but its scope and approach are quite different.

While the former focuses on the imagination and curiosity stimulated by the alphabet, the latter deals more broadly with the history of writing, exploring the origins and development of the alphabet.

Or, in the author's words, "The Alphabet Labyrinth describes what was known or assumed about letters in graphic form over time.

But The Invention of the Alphabet describes how we came to know what we know about this history.” (p. 11) And in this “how,” it analyzes the influence of visual media such as alphabet catalogs, writing practices, and diagrams on our knowledge before empirical science became dominant—and even after the scientific age.

Every attempt to discover the origin and history of the alphabet ends up 'inventing' a new alphabet.

Our knowledge somewhat defines the object of knowledge, and this also applies to writing, the fundamental means of knowledge.

This book provides a breathless overview of the broad academic world of author Haena Jo Drucker, who created the book, and briefly outlines the context surrounding "The Invention of the Alphabet."

This is the author's second book, following the artist book 『Diagrammatic Writing』(2019), translated by one of the translators (Choi Seul-gi), and the first to be introduced as a full-fledged academic book.

Translating the author's writing, which considered not only the content of the text but also its format and letter form, was no easy task. However, in the end, we gave up on guessing at hidden intentions that we might never fully discover, or contacting the author to confirm each and every detail, and opted to interpret the given text as an objective object.

In any case, since the physical properties of a text also imply a certain degree of autonomy of the text, I believe the author will not find this choice absurd.

There is one aspect that is clearly missing or distorted in the Korean version.

Because it is conveyed through Hangul rather than alphabetic characters, this book does not reproduce the original book's unique condition of presenting stories about the alphabet in alphabetic form, which is its self-reflective dimension.

Instead, there are characters on this page that are alphabetic in that they are phonetic, but are also not 'alphabet' in that they do not share a lineage with other alphabets; characters that were invented historically and have been reinvented conceptually and metaphorically many times.

I hope that this unique character will add a new sensory quality to the text and supplement its symbolic dimension.

― When and where did letters appear?

"The Invention of the Alphabet" provides the first intellectual and cultural account of the "origin and development of the alphabet over 4,000 years."

This book covers 2,500 years of history, starting with Herodotus (around 440 BC), who first historically mentioned the alphabet, and explains the circumstances in Chapter 1, "When Did the Alphabet Become 'Greek Letters'?"

The author points out that from the Linear A of the Minoan civilization in the early 2nd millennium BC, which is the earliest form of writing, and the Linear B derived from it around 1600 BC (Chapter 1, pp. 18-19), to the Linear Phoenician script, a relatively standardized alphabetic script in the late 2nd millennium BC, when the alphabet essentially influenced knowledge production as a whole, it functioned as part of the culture of coastal cities such as Tyre, Byblos, and Sidon (Chapter 7, “Modern Archaeology,” pp. 223-224), in other words, this book covers the global history of writing that spans 4,000 years.

While the history of the alphabet has been studied quite accurately, little is known about the historiography of the alphabet.

Among the 4,000 years of history of writing, the author fundamentally deals with the 'history of the alphabet.'

It has the character of a literature study that traces the 'lineage of transmission', 'writing', and 'the citation that established the 'concept' of the alphabet.

This is also a very important and fascinating case study in relation to the history of Western thought.

Because it provides insight into how the physical properties of knowledge production and dissemination give rise to intellectual concepts.

The Cultural History of the Alphabet, the Politics of Alphabetic Literacy

How the Alphabet Spread Around the World

― How did it come to support global communication?

The author approaches archaeological research to establish a genealogy of objects in relation to their historical past.

Because “the nature of the evidence shapes historical claims.”

It combines knowledge of the 'cultural history of the alphabet' in that it explains in detail how the alphabet was formed and developed in the culture of each era, from the early writing systems of ancient times (Mycenaean and Minoan civilizations, the ancient city of Thebes, classical Greece, etc.) to the alphabet we use today.

The author expands the discussion to explore the ‘politics of alphabetic literacy’ in that the invention of the alphabet goes beyond the influence on mankind’s ‘way of thinking’ and ‘way of communication’ to the neurological and physiological effects of the alphabet (“Gene-Culture Coevolution Theory”, Robert Logan, Derek de Kerkhove, Ivan Illich’s study, pp. 334-335) and even reaches the point of defining other cultures by ‘gendering’ them (Leonard Silane’s Analysis of the Alphabet of Ancient Cultures, pp. 342-343).

“In today’s academic world, where decolonization of knowledge is a familiar topic of academic conversation, it is no longer acceptable to think of the alphabet as a neutral technology.

Clearly, the alphabet itself is a complex cultural system, and its dynamics are partly instrumental, partly accidental, and sometimes intentional, producing positive or negative effects.

Standards laws become part of an asymmetrical political structure in which those who set standards have more power than those who follow them.

Literacy, in whatever form it takes, both grants and deprives rights.

… … The role and historical position of the alphabet in producing and disseminating knowledge and imagination cannot be erased without damaging a significant part of our humanity.” (Page 348, note “The Power of the Alphabet and Global Hegemony”)

A fascinating intellectual journey exploring the greatest wonders of human invention.

― From Plato's imagination, Kabbalah, occult knowledge systems, and mystical writings to modern research methods

The author cites and studies numerous historical sources to establish the following fact: “All alphabetic characters originated from the same proto-Semitic script, which spread across Europe, Arabia, Africa, and Southeast Asia, and as a result, visually diversified into Greek, Cyrillic, Tamil, Burmese, Balinese, Roman, and Thai scripts,” and points out the beliefs that have corresponded to each period and intellectual framework.

We also do not overlook the fact that the process by which misunderstandings are formed is part of the long history of knowledge production and dissemination.

In early accounts of the history of the alphabet, the alphabet was considered a 'birth' or a 'gift from God', and for as long as 2,000 years, the alphabet was associated with cosmology and given a semi-divine status in spiritual or religious belief systems.

The origins of the alphabet are a fascinating mixture of myth and partial fact, as evidenced by the extensive literature, including attributions of the alphabet to “the finger of God, to the writing of the stars, to the wandering Jews of the Sinai Peninsula, to the Egyptian god Thoth (Theut), and to the Phoenicians.”

As in the previous examples, the historical knowledge that elucidated the origins of the alphabet was formed based on evidence known at the time and beliefs combined with that evidence, and this became an intellectual heritage that contributed to the establishment of the current orthodoxy.

Plato argued that writing was invented in Egypt, attributing its origin to the work of the Egyptian god Thoth, and introduced a more multifaceted concept of language development (p. 26).

Although not as Plato imagined, Egypt's contribution cannot be denied as having influenced the current orthodoxy.

The desire to imbue the letters of the alphabet with divine powers is central to Kabbalistic thought (Baron van Helmont's Studies, p. 59).

The author notes that these belief systems sought to recognize and explore the "profound power of the alphabet as a driving force."

This was a characteristic shared by other mystical traditions of the Hellenistic world, such as Gnosticism and Pythagorean symbolism, which linked Greek concepts of letters to complex cosmic order. (p. 76, Chapter 3, “The Life of the Lion in the Middle Ages”)

Alphabet also played an important role in occult knowledge systems (cryptography, magical writing, the symbolic system derived from ancient Hermeticism, a field that Trithemius was fascinated by) and mystical writings (Hebrew script with celestial developments, and river crossing writing). However, the author notes that the practice of mixing mythological and existential writings, as seen in the works of William Hurey and Athanasius Kircher, disappeared with the introduction of new contextual visual information (tables) presented in their publications. (p. 200, Chapter 6, “The Harmony of Table Rhetoric and the Alphabet”)

With the introduction of these visual information, the 'celestial characters' and 'magic alphabets' outside of occult and esoteric literature disappeared, and the differences in research methods between the 16th and 17th centuries (incomplete character table form) and the 18th century (a time when the table form of a rational comparative research method, a time when linguistic research became more sophisticated) are pointed out.

The author argues that epigraphic methods were in place at this juncture (p. 269, Chapter 8, "Interpreting the Early Alphabet").

It is revealed that the rich material value of Greco-Latin inscriptions, which were the result of the “curiosity of intrepid travelers who traveled to foreign lands to read and decipher the inscriptions on ancient artifacts such as ruins, rocks, and monuments,” was not systematized as a “study of form and type” until the 17th century.

Epigraphy is a field that emerged in earnest in the 18th and 19th centuries thanks to archaeological discoveries, and was praised by Frank Moore Cross in the 20th century for its fundamental importance of having an “eye for form.”

The study of texts requires knowledge of history, biblical archaeology, and linguistics, but it is only possible if epigraphy (or paleography) forms the foundation.

This suggests that regional research based on a “systematized character type classification” is possible and that history can be concretized.

This was related to nationalism.

The idea that each people had unique roots, and that they invented their own unique writing system or language to match their cultural identity, was an academic fad in the 18th century.

LD

Nelm's 『An Attempt to Study the Origin and Elements of Language and Writing』 is a representative work that supports this.

(Pages 180-181, Chapter 5, “Commentary on Antiquities”)

Alphabet's Power, Global Hegemony

From modern empirical scientific research methods to modern understanding

In summary, this book details, along with fascinating historical facts, the lesser-known scholars who contributed to our "modern understanding" of the history of the alphabet.

Among the researchers mentioned by the author, the main figures are as follows:

Hrabanus Maurus (defending the Ister alphabet), Johannes Trithemius (publishing the first major compendium of printed texts, Polygraphia), Teseo Ambrogio (author of appendices to the various languages in the Compendium of the Chaldean Language), Angelo Rocca (form-oriented arrangement of letters using specimen tables and graphic legends), Thomas Astle (dismissing the creation myths of letters, emphasizing the interconnectedness of Phoenician, Hebrew, and Samaritan scripts in The Origin and Development of Writing), Edmund Fry (publishing Universal Writing, a comprehensive and eclectic collection of letters), Charles Foster (comprising a comprehensive tabular compendium of biblical and rational perspectives on the origin of the alphabet), Isaac Taylor (presenting evidence showing the origin and development of the alphabet), Frank Moore Cross (analyzing the development of the alphabetic scripts that contributed to the formation of the alphabet), Joseph Nabe (compares Greek inscriptions with the various stages of alphabetic development), René Derolles (the study of the runic alphabet). Genealogy, a specialty of scholarly tradition), Benjamin Seth (an epigraphist who created tables with aesthetic properties linked to the empirical approach in The Birth and Development of the Alphabet), and Villemain Waal (who synthesized archaeological, epigraphic, and linguistic evidence to date the spread of writing).

Johana Drucker begins with a key passage in Book V of Herodotus's Histories ("Are writing a gift from Cadmus and the Phoenicians?") and traces the Old Testament's record ("Are writing a gift from God to Moses?") to trace the major debates leading up to the modern era, when empirical science became the standard research method, and arrives at a contemporary concept.

It emphasizes that the codes handed down since ancient times are integrated into the global system of computer media and digital communication networks, and that they are closely related to alphanumeric notation at the level just above binary codes made up of mechanical digits and bits.

This persistent system of alphabetic symbols “exerts its power in the global network of the contemporary world, even in non-alphabetic languages.”

The alphabet is analyzed as a method of organizing information and knowledge according to today's standards, and the identity of the alphabet's letters is characterized by 'endurance' and 'versatility'.

In a communications environment interconnected by a global network, the alphabet, by virtue of its reliance on standards, becomes an essential element of a vast hegemonic system that injects Western bias into various levels of infrastructure.

That is, this instrumental dynamic clearly reveals the politics of alphabetic literacy in contemporary life.

To discuss this active motivation, the author cites a unique perspective based on the animist theory of Luther Marsh.

In his closing remarks, in which he declared that he did not believe evolution would end with humans, he praised the endless possibilities of letter combinations, saying, “What was our XYZ in the long alphabet of life has now become our ABC,” and was optimistic that “there is no combination that cannot be readily taken, no action that cannot be performed.”

Regarding this, Jo Hae-na Drucker states that it is an original and unique insight, but it hits the nail on the head.

This is a poignant portrayal of the dynamics of modern writing.

With the advent of computers, a new frame of reference emerged for understanding the fundamental definition of the alphabet, a set of symbols that now form the basis of digital systems that enable the exchange of encoded information.

The author's discussion outlines aspects of the visual identity of characters, their nature as open sets (as reflected in the work of Douglas Hofstadter), and the identity of Unicode (as a digital character code), and addresses aspects of the shifting paradigm of human knowledge.

He emphasizes that “we are still inventing the alphabet.”

This is precisely why this book has monumental value.

The author's research, which seeks to elucidate the history of the alphabet, reminds us of the significance of how the alphabet was 'invented' anew over time, and integrates research on 'Western history of thought,' 'intellectual history,' 'cultural history,' 'politics of literacy,' and 'digital humanities.'

Translator's Note (excerpts)

― Choi Seong-min (Professor of Visual Design, Seoul Metropolitan University), Choi Seul-gi (Professor of Visual Design, Kyewon University of Art and Design)

… … Published 27 years after the publication of 『The Labyrinth of the Alphabet』, 『The Invention of the Alphabet』 shares the commonality of dealing with the history of the alphabet, but its scope and approach are quite different.

While the former focuses on the imagination and curiosity stimulated by the alphabet, the latter deals more broadly with the history of writing, exploring the origins and development of the alphabet.

Or, in the author's words, "The Alphabet Labyrinth describes what was known or assumed about letters in graphic form over time.

But The Invention of the Alphabet describes how we came to know what we know about this history.” (p. 11) And in this “how,” it analyzes the influence of visual media such as alphabet catalogs, writing practices, and diagrams on our knowledge before empirical science became dominant—and even after the scientific age.

Every attempt to discover the origin and history of the alphabet ends up 'inventing' a new alphabet.

Our knowledge somewhat defines the object of knowledge, and this also applies to writing, the fundamental means of knowledge.

This book provides a breathless overview of the broad academic world of author Haena Jo Drucker, who created the book, and briefly outlines the context surrounding "The Invention of the Alphabet."

This is the author's second book, following the artist book 『Diagrammatic Writing』(2019), translated by one of the translators (Choi Seul-gi), and the first to be introduced as a full-fledged academic book.

Translating the author's writing, which considered not only the content of the text but also its format and letter form, was no easy task. However, in the end, we gave up on guessing at hidden intentions that we might never fully discover, or contacting the author to confirm each and every detail, and opted to interpret the given text as an objective object.

In any case, since the physical properties of a text also imply a certain degree of autonomy of the text, I believe the author will not find this choice absurd.

There is one aspect that is clearly missing or distorted in the Korean version.

Because it is conveyed through Hangul rather than alphabetic characters, this book does not reproduce the original book's unique condition of presenting stories about the alphabet in alphabetic form, which is its self-reflective dimension.

Instead, there are characters on this page that are alphabetic in that they are phonetic, but are also not 'alphabet' in that they do not share a lineage with other alphabets; characters that were invented historically and have been reinvented conceptually and metaphorically many times.

I hope that this unique character will add a new sensory quality to the text and supplement its symbolic dimension.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 24, 2024

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 424 pages | 1,050g | 180*246*28mm

- ISBN13: 9791171176687

- ISBN10: 1171176686

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)