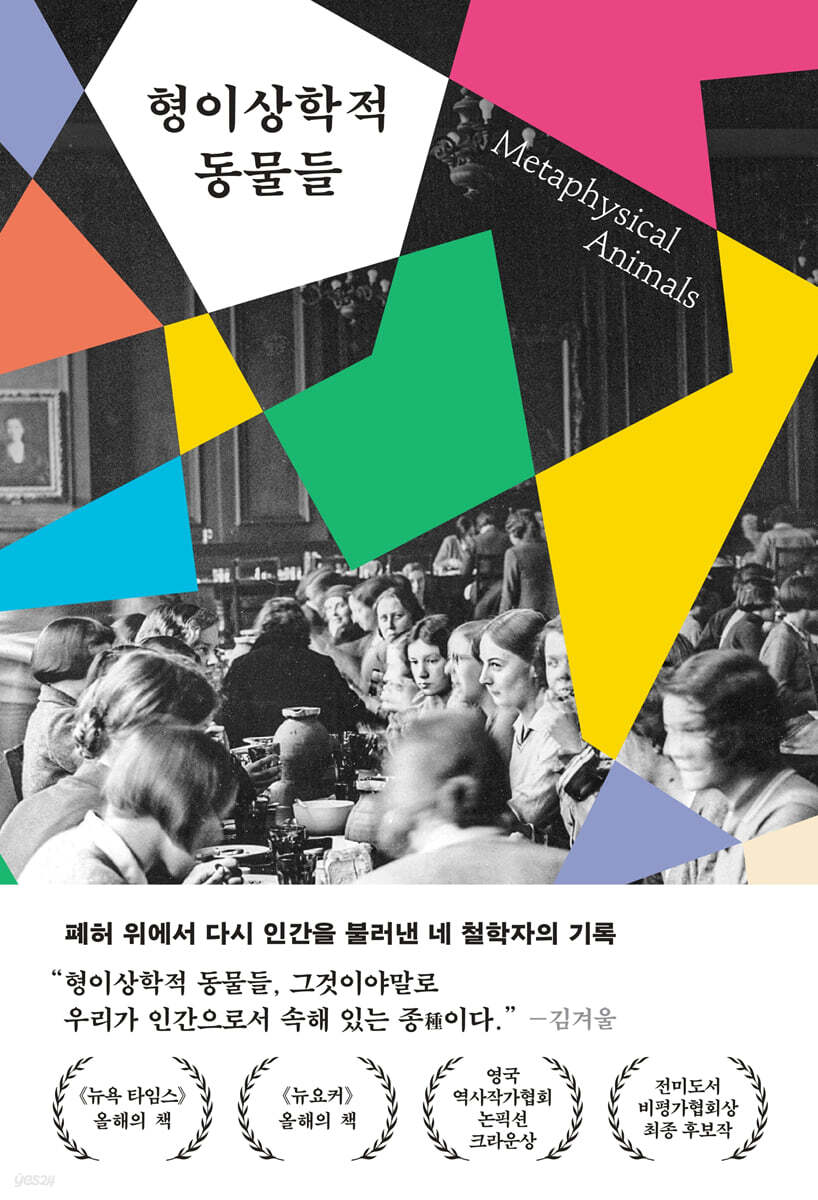

Metaphysical Animals

|

Description

Book Introduction

★The New Yorker Book of the Year

★New York Times Book of the Year

★National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist

★The British Historical Writers' Association Non-Fiction Crown Prize

“What kind of animal is man?”

History begins again in the face of this question.

In the mid-20th century, when Europe was reduced to ashes by World War II, philosophy fell silent.

Logical positivism, which declared the end of metaphysics, was powerless in the face of human existential suffering and moral confusion.

Humans, who had built civilization in the name of reason, lost their own sense of justice in the face of the massacre and destruction caused by the world war, and were unable to explain human destruction through language and logic.

At that very moment, four young female philosophers from Oxford—Elizabeth Anscombe, Philapa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch—revisited the oldest and most fundamental questions in the face of a shattered world.

“What kind of animal is man?”

This question was not simply an attempt to define a concept, but to return philosophy to its place in life.

And soon it extended to the deepest part of life.

“How do human actions acquire meaning?” “What constitutes responsibility?” “How does evil arise?” These four people grappled with these questions in the bombed-out streets, in the daily routine of standing in line with ration cards, and in the interplay of friendship, love, and loss.

Their questions bring philosophy back to human life and connect it with human existence.

It was an achievement made possible by the fact that, in the most inhumane of times, humans were beings who interpreted the world, created meaning, and shaped their own lives.

And now, we stand before that question again.

In an age where wars recur, technology replaces human judgment, and AI and algorithms produce "meaning," we are again asked:

What criteria should guide human behavior, how should we view others, and what responsibilities should we assume? The reflections of these four philosophers are the first sparks of reviving the ethical sensibility our world has lost.

In that sense, this book is not a record of looking back on the past, but rather a most urgent declaration testifying to where we must begin again in an age when humanity is threatened.

★New York Times Book of the Year

★National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist

★The British Historical Writers' Association Non-Fiction Crown Prize

“What kind of animal is man?”

History begins again in the face of this question.

In the mid-20th century, when Europe was reduced to ashes by World War II, philosophy fell silent.

Logical positivism, which declared the end of metaphysics, was powerless in the face of human existential suffering and moral confusion.

Humans, who had built civilization in the name of reason, lost their own sense of justice in the face of the massacre and destruction caused by the world war, and were unable to explain human destruction through language and logic.

At that very moment, four young female philosophers from Oxford—Elizabeth Anscombe, Philapa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch—revisited the oldest and most fundamental questions in the face of a shattered world.

“What kind of animal is man?”

This question was not simply an attempt to define a concept, but to return philosophy to its place in life.

And soon it extended to the deepest part of life.

“How do human actions acquire meaning?” “What constitutes responsibility?” “How does evil arise?” These four people grappled with these questions in the bombed-out streets, in the daily routine of standing in line with ration cards, and in the interplay of friendship, love, and loss.

Their questions bring philosophy back to human life and connect it with human existence.

It was an achievement made possible by the fact that, in the most inhumane of times, humans were beings who interpreted the world, created meaning, and shaped their own lives.

And now, we stand before that question again.

In an age where wars recur, technology replaces human judgment, and AI and algorithms produce "meaning," we are again asked:

What criteria should guide human behavior, how should we view others, and what responsibilities should we assume? The reflections of these four philosophers are the first sparks of reviving the ethical sensibility our world has lost.

In that sense, this book is not a record of looking back on the past, but rather a most urgent declaration testifying to where we must begin again in an age when humanity is threatened.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introductionㆍ7

Charactersㆍ20

Prologue: Philosophy, Standing Before Powerㆍ23

Oxford, May 1956

Chapter 1: The Suppressed Voiceㆍ37

Oxford, October 1938 - September 1939

Chapter 2: In the Maelstrom of Warㆍ105

Oxford, September 1939 - June 1942

Chapter 3: Between Despair and Resistanceㆍ167

June 1942 - August 1945 Cambridge and London

Chapter 4: Rekindling the Flame of Philosophyㆍ231

September 1945 - August 1947 Oxford, Brussels, Graz, Cambridge and Chiswick

Chapter 5: Shouting "No" in One Voiceㆍ297

October 1947 - July 1948 Oxford and Cambridge

Chapter 6: Back to Lifeㆍ343

October 1948 - January 1951 Oxford, Cambridge, Dublin & Vienna

Chapter 7: We Are Metaphysical Animalsㆍ391

May 1950 - February 1955 Newcastle & Oxford

Epilogue: Finally, Towards Humanityㆍ455

Oxford, May 1956

The Story After Thatㆍ468

Translator's Noteㆍ475

Week 478

Referencesㆍ550

Image source: 564

Charactersㆍ20

Prologue: Philosophy, Standing Before Powerㆍ23

Oxford, May 1956

Chapter 1: The Suppressed Voiceㆍ37

Oxford, October 1938 - September 1939

Chapter 2: In the Maelstrom of Warㆍ105

Oxford, September 1939 - June 1942

Chapter 3: Between Despair and Resistanceㆍ167

June 1942 - August 1945 Cambridge and London

Chapter 4: Rekindling the Flame of Philosophyㆍ231

September 1945 - August 1947 Oxford, Brussels, Graz, Cambridge and Chiswick

Chapter 5: Shouting "No" in One Voiceㆍ297

October 1947 - July 1948 Oxford and Cambridge

Chapter 6: Back to Lifeㆍ343

October 1948 - January 1951 Oxford, Cambridge, Dublin & Vienna

Chapter 7: We Are Metaphysical Animalsㆍ391

May 1950 - February 1955 Newcastle & Oxford

Epilogue: Finally, Towards Humanityㆍ455

Oxford, May 1956

The Story After Thatㆍ468

Translator's Noteㆍ475

Week 478

Referencesㆍ550

Image source: 564

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

In an age where metaphysics has come to an end,

Four female philosophers who blossomed on the ruins of war and massacre.

As modern science became almost the only language for explaining the world, and logical positivism and analytic philosophy dominated the philosophical scene in the early 20th century, metaphysics was once declared a 'finished discipline.'

Questions about God and the soul, good and evil, and the ultimate structure of humanity and the world were relegated to the status of "empty wordplay that cannot be proven by experience," and issues of morality and ethics were scattered into psychology, social science, and policy discussions.

The origin of metaphysics, which means 'what comes after physics', dates back to the time of Aristotle.

Metaphysics is often understood as 'the philosophy of the invisible,' but it is actually the name of philosophy's oldest questions: how the world is made, what kind of beings humans are, what we should believe, and what we should be responsible for.

This age-old question resurfaced in the mid-20th century amid the devastation of World War II.

The war shattered all existing standards for understanding humanity, and the clarity of language, solidified by logical positivism and analytical philosophy, could no longer explain the evil and responsibility of humanity revealed by the bombings of Auschwitz, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki.

At that very moment, metaphysics became not an abstract discussion, but the most realistic thought that asked how humans should live again.

In 1939, during the height of the war, Oxford University became a vast empty space.

With most of the male professors and students conscripted, the empty classrooms and libraries were filled with unexpected faces.

Women, conscientious objectors, old professors and exiled scholars from all over Europe.

They soon became deeply dissatisfied with the reality of the philosophy they were confronted with (a philosophy that pursued only linguistic analysis and verifiability, while ignoring human life).

Concepts like good and evil and responsibility were discarded as “meaningless,” and moral judgments were relegated to personal preference.

But it was in that very gap that four women, Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch, began to open up their thinking in a very different direction.

Anscombe delved into the fundamental structure of human action, restored “intention” and “moral reality,” and suggested a new place for ethics to stand in the face of the sudden collapse of intuitionism.

Foote revived the ethics of virtue, character, and responsibility by confronting war photographs with the question, “Why do we want to say this is wrong?”

The 'trolley problem' proposed by Foote became a turning point that questioned the structure of moral judgment.

Against the scientism that reduces humans to mere instinctual machines, Midgley believed that humans should be understood as an integrated being of animals, living things, and social beings.

Her idea was that ethics should be a living discipline where biology, philosophy, and psychology meet.

Murdoch places the center of morality on 'attention' and 'imagination', and believes that how we view others determines what kind of being we become.

These four people deeply penetrated each other's thoughts and lives, and brought back to the center of philosophy the area that logical positivism had dismissed as "meaningless."

Concepts like evil, violence, responsibility, love, concern, and caution found renewed life in their discussions, and moral philosophy and metaphysics were reclaimed as the most fundamental ways in which the human animal understands the world.

What this book captures are the moments when, amidst the ruins, four women forged a new ethical landscape.

“We are metaphysical animals.”

A Chronicle of the Thoughts That Breathed Life into Philosophy

The thinking of your female philosophers was never isolated.

The exhibition Oxford they walked into was like a vast fabric where various intellects collided and intertwined.

At the center of it all was Elizabeth Anscombe, trusted by Wittgenstein, who translated and edited his most important legacy, the Philosophical Investigations.

Elizabeth, obsessed with questions like divine foreknowledge, just war, and the identity of the body, was almost the only real conversation partner for Wittgenstein, who wanted a "truly thoughtful student," and in his will, Wittgenstein left her the copyright to his unpublished works and a significant portion of his estate, entrusting her with his philosophical legacy.

In this close exchange, Elizabeth not only translated Wittgenstein's thoughts, but also solidified her own philosophical position.

How that philosophy translates into reality is dramatically revealed in a scene from 1956.

That year, Anscombe addressed Oxford faculty members about former U.S. President Harry S., who had ordered the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Harry S. Truman

Truman) publicly opposes awarding an honorary degree.

How could an act that led to the deaths of tens of thousands of innocent people be compatible with "honor"? Why did other professors fail to see this judgment, so self-evident to her? Anscombe struggled almost alone to push her point, and this was the moment when her philosophy, which insisted on never losing sight of human action, intention, and moral reality, finally ignited in the real world.

Around these four philosophers there was a richer solidarity of thought.

Susan Stebbing, Britain's first female professor of philosophy, laid the intellectual foundation for later female philosophers by highlighting the importance of clear thinking.

Dorothy Emmet provided a realistic foundation for ethics by viewing moral judgments not as mere intuitions but as stemming from the relationships and ways of life we believe to be good.

R., who thought about the problems of history, imagination, and practice together.

G. Collingwood showed that the order of the world and experience itself are the subjects of metaphysics, and Donald MacKinnon showed that A.

J. Ayer warned that the moment logical positivism erases metaphysics, the soul of the human animal is threatened.

All these flows are J.

L. Austin, A.

It formed the philosophical structure of Oxford at the time, achieving the rigor and tension of analytic philosophy led by J. Ayer.

Besides these, there are philosophers who preserved the spark of metaphysics at the time.

HH

Price, H.

WB

Joseph, Carlotta Labowsky, and Mary Glover.

Although unfamiliar to us, these are important names that supported the philosophical landscape of this era.

On this solid foundation, the conversation between the four people was broad and deep.

Between Elizabeth's house and Philippa's kitchen, the lecture halls of Somerville and St. Anne's College, the parks of Christchurch, and the pubs and teahouses, they discussed memory, truth, and meaning endlessly.

From Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas to Descartes, Kant, Kierkegaard, and Wittgenstein, names spanning the classical and modern eras are revived as questions that touch upon human life in the conversations of four people.

Metaphysical Animals meticulously reconstructs this vast network of relationships, vividly revealing that philosophy is born not on a desk, but among people, amidst friendship and debate.

“How do we become human again?”

In the Age of AI and War, Questions Resurfacing About Humanity

In the world we live in today, war is no longer an event of the distant past.

From the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the war in Ukraine, the civil war in Myanmar, to the silent conflicts in Africa, war and destruction continue to rage everywhere today.

The efficiency brought about by science and technology has brought convenience, but has also put humanity in increasing danger. The biggest problem in the AI era is that humans no longer experience the process of responsibility and deliberation. AI and algorithms reduce the world to measurable information.

But, “What is right?”, “How should we view others?”, “How should we understand suffering?” are complex areas of human beings that cannot be measured in the first place.

Yet, AI and algorithms process human deliberation and judgment and even produce ‘meaning.’

As a result, ‘humanity’ is becoming increasingly blurred, and even its standards are becoming ambiguous.

The aftermath dims the importance of relationships, responsibility, and understanding the minds of others.

It is at this very point that the questions in this book become strikingly relevant.

There is only one key point that this book shows.

Human moral reasoning begins not at a quiet and orderly table, but amid the cracks of the world and the complexities of life.

Just as four female philosophers reclaimed human action and responsibility for meaning amid the ruins of war, so too did men think during the war.

The representative figure is Richard Hare.

His confession that “if there had been no war, I would not have become a philosopher” came after he encountered scenes of Japanese prisoners of war committing seppuku and of overseers treating prisoners driven to their deaths with indifference.

At that moment he realized.

'Right' and 'wrong' are not matters of intuition or emotion, and existing ethical theories are speechless in the face of this reality.

Richard Hare writes, “If moral intuitions correspond to objective moral reality, such stark and insurmountable clashes of intuitions should not be possible” (p.

303)” I thought.

This realization is intricately intertwined with the questions that four female philosophers have reached.

War has shattered moral intuitions, technology has shaken the very fabric of judgment, and a social climate that erases human complexity in the name of efficiency and fairness is weakening even our sense of care and connection.

Elizabeth Anscombe made this point clearly even at the time.

Elizabeth Anscombe argues that the postwar welfare system “lost the goals of ‘justice’ and ‘tolerance’ based on metaphysical explanations” (p.

427)” He criticized the time when the sense of care was erased in the name of ‘efficiency,’ ‘fairness,’ and ‘public welfare.’

He argued that preventing elderly people living alone from living at home because they do not meet the standards is ethics stripped of metaphysics.

“The kindness of the wicked is cruel” (p.

Elizabeth's words, “427)” are still applicable to today's society.

The moment values like efficiency, productivity, convenience, and fairness become the criteria for judging human life and relationships, the ethics of care and responsibility are erased.

“Almost all the great European philosophers were single men. (p.

431)” This point by Mary Midgley reveals what experiences philosophy has been built on.

If philosophy were practiced by philosophers writing while their babies slept in the next room, by mothers concerned about their infants' health, and by people who spent time in diverse communities, would philosophy have the same face it does today? Mary Midgley's question also demonstrates that care and relationships, hurt and responsibility, and the ability to read others' minds are prerequisites for philosophical thought.

This is a sense that today's world has completely lost. In an age where AI replaces judgment, technology designs desires, and war and violence disrupt daily life, we are forced to ask ourselves this question again.

“What will we see, how will we feel, and what will we become?”

The thoughts of your philosophers are a starting point for questioning the ethical sensibility needed in this era.

In that sense, this book is not a chronicle restoring the history of philosophy from the past, but rather a contemporary declaration that tells us where philosophy must begin again in a situation where humanity is in crisis.

Four female philosophers who blossomed on the ruins of war and massacre.

As modern science became almost the only language for explaining the world, and logical positivism and analytic philosophy dominated the philosophical scene in the early 20th century, metaphysics was once declared a 'finished discipline.'

Questions about God and the soul, good and evil, and the ultimate structure of humanity and the world were relegated to the status of "empty wordplay that cannot be proven by experience," and issues of morality and ethics were scattered into psychology, social science, and policy discussions.

The origin of metaphysics, which means 'what comes after physics', dates back to the time of Aristotle.

Metaphysics is often understood as 'the philosophy of the invisible,' but it is actually the name of philosophy's oldest questions: how the world is made, what kind of beings humans are, what we should believe, and what we should be responsible for.

This age-old question resurfaced in the mid-20th century amid the devastation of World War II.

The war shattered all existing standards for understanding humanity, and the clarity of language, solidified by logical positivism and analytical philosophy, could no longer explain the evil and responsibility of humanity revealed by the bombings of Auschwitz, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki.

At that very moment, metaphysics became not an abstract discussion, but the most realistic thought that asked how humans should live again.

In 1939, during the height of the war, Oxford University became a vast empty space.

With most of the male professors and students conscripted, the empty classrooms and libraries were filled with unexpected faces.

Women, conscientious objectors, old professors and exiled scholars from all over Europe.

They soon became deeply dissatisfied with the reality of the philosophy they were confronted with (a philosophy that pursued only linguistic analysis and verifiability, while ignoring human life).

Concepts like good and evil and responsibility were discarded as “meaningless,” and moral judgments were relegated to personal preference.

But it was in that very gap that four women, Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch, began to open up their thinking in a very different direction.

Anscombe delved into the fundamental structure of human action, restored “intention” and “moral reality,” and suggested a new place for ethics to stand in the face of the sudden collapse of intuitionism.

Foote revived the ethics of virtue, character, and responsibility by confronting war photographs with the question, “Why do we want to say this is wrong?”

The 'trolley problem' proposed by Foote became a turning point that questioned the structure of moral judgment.

Against the scientism that reduces humans to mere instinctual machines, Midgley believed that humans should be understood as an integrated being of animals, living things, and social beings.

Her idea was that ethics should be a living discipline where biology, philosophy, and psychology meet.

Murdoch places the center of morality on 'attention' and 'imagination', and believes that how we view others determines what kind of being we become.

These four people deeply penetrated each other's thoughts and lives, and brought back to the center of philosophy the area that logical positivism had dismissed as "meaningless."

Concepts like evil, violence, responsibility, love, concern, and caution found renewed life in their discussions, and moral philosophy and metaphysics were reclaimed as the most fundamental ways in which the human animal understands the world.

What this book captures are the moments when, amidst the ruins, four women forged a new ethical landscape.

“We are metaphysical animals.”

A Chronicle of the Thoughts That Breathed Life into Philosophy

The thinking of your female philosophers was never isolated.

The exhibition Oxford they walked into was like a vast fabric where various intellects collided and intertwined.

At the center of it all was Elizabeth Anscombe, trusted by Wittgenstein, who translated and edited his most important legacy, the Philosophical Investigations.

Elizabeth, obsessed with questions like divine foreknowledge, just war, and the identity of the body, was almost the only real conversation partner for Wittgenstein, who wanted a "truly thoughtful student," and in his will, Wittgenstein left her the copyright to his unpublished works and a significant portion of his estate, entrusting her with his philosophical legacy.

In this close exchange, Elizabeth not only translated Wittgenstein's thoughts, but also solidified her own philosophical position.

How that philosophy translates into reality is dramatically revealed in a scene from 1956.

That year, Anscombe addressed Oxford faculty members about former U.S. President Harry S., who had ordered the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Harry S. Truman

Truman) publicly opposes awarding an honorary degree.

How could an act that led to the deaths of tens of thousands of innocent people be compatible with "honor"? Why did other professors fail to see this judgment, so self-evident to her? Anscombe struggled almost alone to push her point, and this was the moment when her philosophy, which insisted on never losing sight of human action, intention, and moral reality, finally ignited in the real world.

Around these four philosophers there was a richer solidarity of thought.

Susan Stebbing, Britain's first female professor of philosophy, laid the intellectual foundation for later female philosophers by highlighting the importance of clear thinking.

Dorothy Emmet provided a realistic foundation for ethics by viewing moral judgments not as mere intuitions but as stemming from the relationships and ways of life we believe to be good.

R., who thought about the problems of history, imagination, and practice together.

G. Collingwood showed that the order of the world and experience itself are the subjects of metaphysics, and Donald MacKinnon showed that A.

J. Ayer warned that the moment logical positivism erases metaphysics, the soul of the human animal is threatened.

All these flows are J.

L. Austin, A.

It formed the philosophical structure of Oxford at the time, achieving the rigor and tension of analytic philosophy led by J. Ayer.

Besides these, there are philosophers who preserved the spark of metaphysics at the time.

HH

Price, H.

WB

Joseph, Carlotta Labowsky, and Mary Glover.

Although unfamiliar to us, these are important names that supported the philosophical landscape of this era.

On this solid foundation, the conversation between the four people was broad and deep.

Between Elizabeth's house and Philippa's kitchen, the lecture halls of Somerville and St. Anne's College, the parks of Christchurch, and the pubs and teahouses, they discussed memory, truth, and meaning endlessly.

From Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas to Descartes, Kant, Kierkegaard, and Wittgenstein, names spanning the classical and modern eras are revived as questions that touch upon human life in the conversations of four people.

Metaphysical Animals meticulously reconstructs this vast network of relationships, vividly revealing that philosophy is born not on a desk, but among people, amidst friendship and debate.

“How do we become human again?”

In the Age of AI and War, Questions Resurfacing About Humanity

In the world we live in today, war is no longer an event of the distant past.

From the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the war in Ukraine, the civil war in Myanmar, to the silent conflicts in Africa, war and destruction continue to rage everywhere today.

The efficiency brought about by science and technology has brought convenience, but has also put humanity in increasing danger. The biggest problem in the AI era is that humans no longer experience the process of responsibility and deliberation. AI and algorithms reduce the world to measurable information.

But, “What is right?”, “How should we view others?”, “How should we understand suffering?” are complex areas of human beings that cannot be measured in the first place.

Yet, AI and algorithms process human deliberation and judgment and even produce ‘meaning.’

As a result, ‘humanity’ is becoming increasingly blurred, and even its standards are becoming ambiguous.

The aftermath dims the importance of relationships, responsibility, and understanding the minds of others.

It is at this very point that the questions in this book become strikingly relevant.

There is only one key point that this book shows.

Human moral reasoning begins not at a quiet and orderly table, but amid the cracks of the world and the complexities of life.

Just as four female philosophers reclaimed human action and responsibility for meaning amid the ruins of war, so too did men think during the war.

The representative figure is Richard Hare.

His confession that “if there had been no war, I would not have become a philosopher” came after he encountered scenes of Japanese prisoners of war committing seppuku and of overseers treating prisoners driven to their deaths with indifference.

At that moment he realized.

'Right' and 'wrong' are not matters of intuition or emotion, and existing ethical theories are speechless in the face of this reality.

Richard Hare writes, “If moral intuitions correspond to objective moral reality, such stark and insurmountable clashes of intuitions should not be possible” (p.

303)” I thought.

This realization is intricately intertwined with the questions that four female philosophers have reached.

War has shattered moral intuitions, technology has shaken the very fabric of judgment, and a social climate that erases human complexity in the name of efficiency and fairness is weakening even our sense of care and connection.

Elizabeth Anscombe made this point clearly even at the time.

Elizabeth Anscombe argues that the postwar welfare system “lost the goals of ‘justice’ and ‘tolerance’ based on metaphysical explanations” (p.

427)” He criticized the time when the sense of care was erased in the name of ‘efficiency,’ ‘fairness,’ and ‘public welfare.’

He argued that preventing elderly people living alone from living at home because they do not meet the standards is ethics stripped of metaphysics.

“The kindness of the wicked is cruel” (p.

Elizabeth's words, “427)” are still applicable to today's society.

The moment values like efficiency, productivity, convenience, and fairness become the criteria for judging human life and relationships, the ethics of care and responsibility are erased.

“Almost all the great European philosophers were single men. (p.

431)” This point by Mary Midgley reveals what experiences philosophy has been built on.

If philosophy were practiced by philosophers writing while their babies slept in the next room, by mothers concerned about their infants' health, and by people who spent time in diverse communities, would philosophy have the same face it does today? Mary Midgley's question also demonstrates that care and relationships, hurt and responsibility, and the ability to read others' minds are prerequisites for philosophical thought.

This is a sense that today's world has completely lost. In an age where AI replaces judgment, technology designs desires, and war and violence disrupt daily life, we are forced to ask ourselves this question again.

“What will we see, how will we feel, and what will we become?”

The thoughts of your philosophers are a starting point for questioning the ethical sensibility needed in this era.

In that sense, this book is not a chronicle restoring the history of philosophy from the past, but rather a contemporary declaration that tells us where philosophy must begin again in a situation where humanity is in crisis.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 28, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 568 pages | 792g | 150*220*27mm

- ISBN13: 9791166893858

- ISBN10: 1166893855

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)