digital detox

|

Description

Book Introduction

People feel that 'daily life is becoming more convenient' as technology advances.

Are we really working less and living more peacefully today?

★KAIST Professor Jaeseung Jeong strongly recommends Anna Lemke's "Dopamine Nation"!

★Researcher Featured in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal

★Productivity expert at global companies such as Google and Microsoft

ChatGPT, YouTube, Netflix, various social media platforms, etc. Today, people use various digital tools all day long.

During this process, the brain undergoes constant 'context switching' and fatigue accumulates.

The anxiety and impatience that follows, "Who sent that email? I need to check it right now," quickly leads to a failure of immersion.

People are experiencing classic symptoms of digital burnout, such as staring at their screens in a brain-numbing state or scrolling endlessly.

So how should modern people solve this problem?

Paul Leonardi, who has advised global companies such as Google, Microsoft, and McKinsey on productivity, emphasizes that completely blocking digital tools is not a realistic solution.

The crux of the problem lies not in the digital devices themselves, but in our 'way of using' them.

The author presents eight practical rules to address this, explaining that these rules are not simply a matter of moderation, but rather a strategic design for restoring energy.

In other words, ‘digital detox’ is not an avoidance strategy, but a strategy for effective recovery.

If you're suffering from mental and physical fatigue due to digital burnout, or have noticed the early signs of it, "Digital Detox" will help you reestablish your relationship with digital devices and regain a more vibrant and balanced life.

Are we really working less and living more peacefully today?

★KAIST Professor Jaeseung Jeong strongly recommends Anna Lemke's "Dopamine Nation"!

★Researcher Featured in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal

★Productivity expert at global companies such as Google and Microsoft

ChatGPT, YouTube, Netflix, various social media platforms, etc. Today, people use various digital tools all day long.

During this process, the brain undergoes constant 'context switching' and fatigue accumulates.

The anxiety and impatience that follows, "Who sent that email? I need to check it right now," quickly leads to a failure of immersion.

People are experiencing classic symptoms of digital burnout, such as staring at their screens in a brain-numbing state or scrolling endlessly.

So how should modern people solve this problem?

Paul Leonardi, who has advised global companies such as Google, Microsoft, and McKinsey on productivity, emphasizes that completely blocking digital tools is not a realistic solution.

The crux of the problem lies not in the digital devices themselves, but in our 'way of using' them.

The author presents eight practical rules to address this, explaining that these rules are not simply a matter of moderation, but rather a strategic design for restoring energy.

In other words, ‘digital detox’ is not an avoidance strategy, but a strategy for effective recovery.

If you're suffering from mental and physical fatigue due to digital burnout, or have noticed the early signs of it, "Digital Detox" will help you reestablish your relationship with digital devices and regain a more vibrant and balanced life.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue: I have so many useful skills, so why do I still feel tired?

Part 1: What We've Lost in Digital Overload

Chapter 1 Attention: Endless Scrolling and the Failure of Immersion

Chapter 2 Inference: Distorted Analogies and Evaluation

Chapter 3: Emotions: The Uncomfortable Feelings You Feel on Screen

Part 2: Eight Rules for a Digital Detox

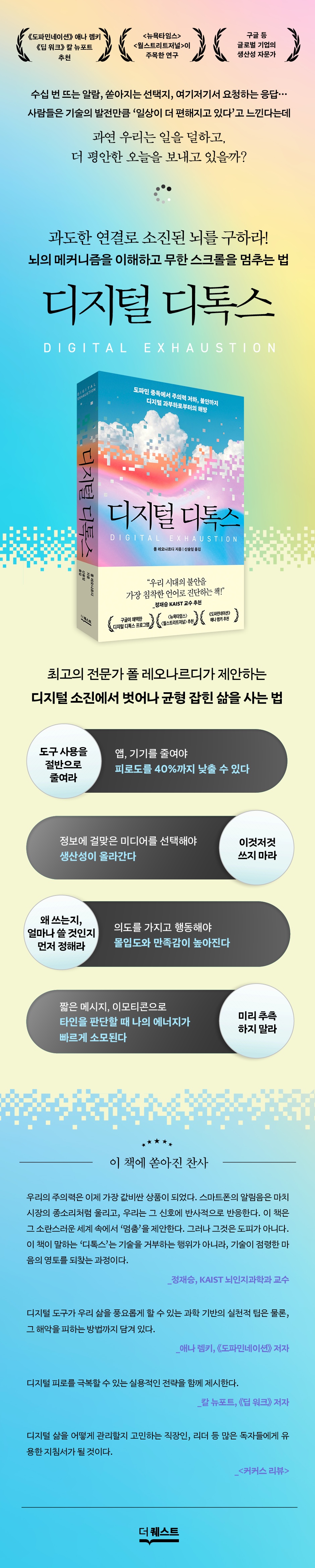

Chapter 4 Rule 1: Cut Your Tools in Half

Chapter 5 Rule 2: Match Media to Information

Chapter 6 Rule 3: Find the optimal combination of batching and streaming.

Chapter 7 Rule 4: Wait Before Responding

Chapter 8 Rule 5: Don't Guess

Chapter 9 Rule 6: Act with Intention

Chapter 10 Rule 7: Learn Indirectly

Chapter 11 Rule 8: Stay in the present moment

Part 3: Finding Balance Between Your Current Life and the Digital World

Chapter 12: Prescription for Organization

Chapter 13: Suggestions for Parents Raising Digital Natives

Chapter 14: Living and Working with AI

Epilogue: In the Age of Technology, Reclaim Control of Your Life

supplement

annotation

Part 1: What We've Lost in Digital Overload

Chapter 1 Attention: Endless Scrolling and the Failure of Immersion

Chapter 2 Inference: Distorted Analogies and Evaluation

Chapter 3: Emotions: The Uncomfortable Feelings You Feel on Screen

Part 2: Eight Rules for a Digital Detox

Chapter 4 Rule 1: Cut Your Tools in Half

Chapter 5 Rule 2: Match Media to Information

Chapter 6 Rule 3: Find the optimal combination of batching and streaming.

Chapter 7 Rule 4: Wait Before Responding

Chapter 8 Rule 5: Don't Guess

Chapter 9 Rule 6: Act with Intention

Chapter 10 Rule 7: Learn Indirectly

Chapter 11 Rule 8: Stay in the present moment

Part 3: Finding Balance Between Your Current Life and the Digital World

Chapter 12: Prescription for Organization

Chapter 13: Suggestions for Parents Raising Digital Natives

Chapter 14: Living and Working with AI

Epilogue: In the Age of Technology, Reclaim Control of Your Life

supplement

annotation

Detailed image

Into the book

Cognitive scientists have named this dramatic shift in attention "context switching."

When we need to switch contexts, our brains must shift from cognitive processing related to the current task and reorient themselves to the demands of the next task.

If you switch from watching a TikTok video about cute hairstyles to a video about trendy shoes, the shift in attention doesn't actually activate the command center of your prefrontal cortex and cause new neurons to fire.

When context changes and new and different cognitive processing is required to understand information or perform a task, the aforementioned process of disconnection and reconnection occurs, consuming the brain's limited energy.

At this time, cortisol is secreted to provide the instantaneous energy needed for the transition.

Cortisol secretion has serious side effects.

Cognitive exhaustion is exacerbated when these stress hormones release a burst of energy.

Just as there are different types of context switching, the way we shift our attention also affects how exhausted we are.

There are three main types of context switching that are most common and place the greatest burden on our remaining cognitive energy.

It is a transition between modality, domain, and arena.

The problem Vicente experiences is a phenomenon called 'attention residue', which occurs when a person is unable to fully engage with the current task and some of their attention is diverted to other areas of work.

Sophie Leroy, a business professor at the University of Washington, explains:

“Attentional residue occurs when you fail to complete a task or are interrupted and then feel the need to finish it quickly.

Our brains have a hard time forgetting things we haven't done and keep them in a corner of our minds.

“Even when you’re trying to focus on another task,” says Gloria Mark, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, who has probably done more research on the effects of shifting attention between domains than anyone else.

She compares our minds to a whiteboard.

“There are times when you can’t completely erase the whiteboard.

Then, the letters written on the blackboard remain faintly.

Something similar happens in our heads, and the residue interferes with our current work.”

--- From "Chapter 1 Attention: Endless Scrolling and the Failure of Immersion"

Why is it so tiring to see yourself on screen? Research suggests that it's because seeing yourself reflected in real-time video and responding to others on camera increases our cognitive load.

Nonverbal communication, which can be handled naturally in face-to-face situations, requires effort online, which increases cognitive load.

For example, when talking about the size of something, you might stretch out your arm, but then realize that your arm is out of the camera and cannot be seen by the person on the other side of the screen, so you quickly withdraw it.

When communicating face-to-face, we don't give much thought to these nonverbal behaviors, but in front of a camera with a narrow field of vision and a stare that pierces us, we become conscious of our own behavior, constantly monitoring and adjusting our actions.

Another reason cognitive load increases is that we have to imagine what the camera can't see.

Recognizing that we cannot see the whole picture, we try to compensate for this.

--- From "Chapter 2 Inference: Distorted Inference and Evaluation"

This term, recently added to the Oxford English Dictionary, means 'a person who (obsessively) searches for health information on the Internet.'

Cyberchondria are dissatisfied with the vast amount of information they have about the condition they may have, and feel anxious that they are missing out on better information that might be out there somewhere.

Librarians regularly discuss how to help patrons cope with information anxiety.

Ashley Eklof, chief librarian at BiblioTech in San Antonio, Texas, explains that information anxiety is “driven by the desire to take in as much information as possible, coupled with feeling overwhelmed by the amount of information being filtered through.”

Because digital tools provide us with so many choices across all areas of our lives, we also have an inordinate amount of opportunities to worry about whether we're making the right choice.

--- From "Chapter 3 Emotions: Uncomfortable Emotions Felt on the Screen"

You need to decide whether your task is a collective or sequential task that requires you to 'convey' information to others, or an interactive task that requires you to 'converge' to a single meaning or mutual understanding.

If you need to convey information, you can use digital tools that transmit text-based information asynchronously or send documents or images that clarify the message.

If you're sending information explaining what you did or asking the other person to pick up where you left off, they need time to digest your message.

In this case, the most appropriate technology is one that doesn't require an immediate answer and doesn't convey unnecessary clues that obscure key data.

However, if you need to converge on a common understanding or produce a common outcome, you need to choose a technology that allows for real-time collaboration by exchanging various clues.

When it comes to discussing each other's understanding of a situation, reaching a consensus, and finding ways for each part to fit together harmoniously, progress is slowed down if active discussion and rapid feedback are not provided.

--- From "Chapter 5 Rule 2: Match Media to Information"

Studies have shown that when we can delay our response time, allowing us to think a little more deeply and carefully refine our message, we are more satisfied with the responses we send, our responses are more comprehensive, more aligned with the recipient's needs, and we build a deeper sense of intimacy with them.

In short, people who delay their responses are more confident in the messages they send and are more considerate of the needs of others.

These results apply equally to all asynchronous digital tools, including email, text messages, messaging platforms, and social media.

Walter's findings, along with several other pieces of evidence supporting his "social information processing model," lend credence to the first part of Marcel's theory: that delayed responses can lead to more informative responses.

--- From "Chapter 7 Rule 4: Wait Before Responding"

“Of all the things that positively impact the inner workings of our lives, the most powerful is progress in meaningful work.” When we feel we are moving toward important goals, when we feel we are taking purposeful steps, we experience a sense of well-being.

On the other hand, when we feel like we are standing still, or more seriously, when we experience regression, we become exhausted.

The feeling of progress is energizing and prevents burnout.

What does progress mean? How do we know we're moving forward?

--- From “Chapter 9 Rule 6: Act with Intention”

People like Mariana who are able to achieve immersion in non-digital areas didn't choose these activities randomly.

They found what I call a 'complementary opposite' activity.

Complementary counter-activities are activities that are diametrically opposed to your primary occupation in terms of the physical skills required, the tools used, the location of the activity, and of course, the digital technologies used.

Although they are polar opposites in many ways, they are complementary to what we do in the workplace in that they both require analytical reasoning and critical thinking.

The reason I introduced Mariana's tiling as an example in this chapter is because it was easy to explain as it was similar to the complementary opposition activity I chose.

--- From "Chapter 11 Rule 8: Stay in the Present Moment"

There has been considerable research on the impact of how managers frame new technologies.

All studies convey the same message.

This means that when employees access new technologies at work or evaluate their experiences using them, they use what they hear from their managers as a benchmark.

Unfortunately, research shows that managers often don't know what message they're sending.

However, we cannot solely blame the managers.

Because the impact of new technologies is quite difficult to predict.

My great colleague, Steve Barley, one of the world's leading authorities on technology and organizational change, writes:

“After nearly 40 years of studying work, technology, and organizations, I've come to the conclusion that there's only one certainty about technological change:

In technological change, we rarely get what we expect, and sometimes we don't even get what we expect.

But whatever happens, it happens.”

When we need to switch contexts, our brains must shift from cognitive processing related to the current task and reorient themselves to the demands of the next task.

If you switch from watching a TikTok video about cute hairstyles to a video about trendy shoes, the shift in attention doesn't actually activate the command center of your prefrontal cortex and cause new neurons to fire.

When context changes and new and different cognitive processing is required to understand information or perform a task, the aforementioned process of disconnection and reconnection occurs, consuming the brain's limited energy.

At this time, cortisol is secreted to provide the instantaneous energy needed for the transition.

Cortisol secretion has serious side effects.

Cognitive exhaustion is exacerbated when these stress hormones release a burst of energy.

Just as there are different types of context switching, the way we shift our attention also affects how exhausted we are.

There are three main types of context switching that are most common and place the greatest burden on our remaining cognitive energy.

It is a transition between modality, domain, and arena.

The problem Vicente experiences is a phenomenon called 'attention residue', which occurs when a person is unable to fully engage with the current task and some of their attention is diverted to other areas of work.

Sophie Leroy, a business professor at the University of Washington, explains:

“Attentional residue occurs when you fail to complete a task or are interrupted and then feel the need to finish it quickly.

Our brains have a hard time forgetting things we haven't done and keep them in a corner of our minds.

“Even when you’re trying to focus on another task,” says Gloria Mark, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, who has probably done more research on the effects of shifting attention between domains than anyone else.

She compares our minds to a whiteboard.

“There are times when you can’t completely erase the whiteboard.

Then, the letters written on the blackboard remain faintly.

Something similar happens in our heads, and the residue interferes with our current work.”

--- From "Chapter 1 Attention: Endless Scrolling and the Failure of Immersion"

Why is it so tiring to see yourself on screen? Research suggests that it's because seeing yourself reflected in real-time video and responding to others on camera increases our cognitive load.

Nonverbal communication, which can be handled naturally in face-to-face situations, requires effort online, which increases cognitive load.

For example, when talking about the size of something, you might stretch out your arm, but then realize that your arm is out of the camera and cannot be seen by the person on the other side of the screen, so you quickly withdraw it.

When communicating face-to-face, we don't give much thought to these nonverbal behaviors, but in front of a camera with a narrow field of vision and a stare that pierces us, we become conscious of our own behavior, constantly monitoring and adjusting our actions.

Another reason cognitive load increases is that we have to imagine what the camera can't see.

Recognizing that we cannot see the whole picture, we try to compensate for this.

--- From "Chapter 2 Inference: Distorted Inference and Evaluation"

This term, recently added to the Oxford English Dictionary, means 'a person who (obsessively) searches for health information on the Internet.'

Cyberchondria are dissatisfied with the vast amount of information they have about the condition they may have, and feel anxious that they are missing out on better information that might be out there somewhere.

Librarians regularly discuss how to help patrons cope with information anxiety.

Ashley Eklof, chief librarian at BiblioTech in San Antonio, Texas, explains that information anxiety is “driven by the desire to take in as much information as possible, coupled with feeling overwhelmed by the amount of information being filtered through.”

Because digital tools provide us with so many choices across all areas of our lives, we also have an inordinate amount of opportunities to worry about whether we're making the right choice.

--- From "Chapter 3 Emotions: Uncomfortable Emotions Felt on the Screen"

You need to decide whether your task is a collective or sequential task that requires you to 'convey' information to others, or an interactive task that requires you to 'converge' to a single meaning or mutual understanding.

If you need to convey information, you can use digital tools that transmit text-based information asynchronously or send documents or images that clarify the message.

If you're sending information explaining what you did or asking the other person to pick up where you left off, they need time to digest your message.

In this case, the most appropriate technology is one that doesn't require an immediate answer and doesn't convey unnecessary clues that obscure key data.

However, if you need to converge on a common understanding or produce a common outcome, you need to choose a technology that allows for real-time collaboration by exchanging various clues.

When it comes to discussing each other's understanding of a situation, reaching a consensus, and finding ways for each part to fit together harmoniously, progress is slowed down if active discussion and rapid feedback are not provided.

--- From "Chapter 5 Rule 2: Match Media to Information"

Studies have shown that when we can delay our response time, allowing us to think a little more deeply and carefully refine our message, we are more satisfied with the responses we send, our responses are more comprehensive, more aligned with the recipient's needs, and we build a deeper sense of intimacy with them.

In short, people who delay their responses are more confident in the messages they send and are more considerate of the needs of others.

These results apply equally to all asynchronous digital tools, including email, text messages, messaging platforms, and social media.

Walter's findings, along with several other pieces of evidence supporting his "social information processing model," lend credence to the first part of Marcel's theory: that delayed responses can lead to more informative responses.

--- From "Chapter 7 Rule 4: Wait Before Responding"

“Of all the things that positively impact the inner workings of our lives, the most powerful is progress in meaningful work.” When we feel we are moving toward important goals, when we feel we are taking purposeful steps, we experience a sense of well-being.

On the other hand, when we feel like we are standing still, or more seriously, when we experience regression, we become exhausted.

The feeling of progress is energizing and prevents burnout.

What does progress mean? How do we know we're moving forward?

--- From “Chapter 9 Rule 6: Act with Intention”

People like Mariana who are able to achieve immersion in non-digital areas didn't choose these activities randomly.

They found what I call a 'complementary opposite' activity.

Complementary counter-activities are activities that are diametrically opposed to your primary occupation in terms of the physical skills required, the tools used, the location of the activity, and of course, the digital technologies used.

Although they are polar opposites in many ways, they are complementary to what we do in the workplace in that they both require analytical reasoning and critical thinking.

The reason I introduced Mariana's tiling as an example in this chapter is because it was easy to explain as it was similar to the complementary opposition activity I chose.

--- From "Chapter 11 Rule 8: Stay in the Present Moment"

There has been considerable research on the impact of how managers frame new technologies.

All studies convey the same message.

This means that when employees access new technologies at work or evaluate their experiences using them, they use what they hear from their managers as a benchmark.

Unfortunately, research shows that managers often don't know what message they're sending.

However, we cannot solely blame the managers.

Because the impact of new technologies is quite difficult to predict.

My great colleague, Steve Barley, one of the world's leading authorities on technology and organizational change, writes:

“After nearly 40 years of studying work, technology, and organizations, I've come to the conclusion that there's only one certainty about technological change:

In technological change, we rarely get what we expect, and sometimes we don't even get what we expect.

But whatever happens, it happens.”

--- From "Chapter 12 Prescriptions for Organization"

Publisher's Review

“I just watched Netflix all day, why am I so tired?”

Scientific diagnosis and solutions for those who can't put their smartphones down 24 hours a day!

In today's world, where digital tools prioritizing convenience and efficiency have become ubiquitous, have our lives truly improved? Paul Leonardi, a professor of technology management at the University of California and author of "Digital Detox," has spent the past two decades researching the impact of digital technology on the human body and mind.

The authors specifically surveyed 12 countries on the question, “How tired do you feel when using digital technology?” and found that the average fatigue score rose significantly from 2.6 in 2002 to 5.5 in 2022.

This isn't just general work-related stress; it's a clear sign that digital technology is directly taxing the human brain and emotional circuitry.

He defines this state as “not simply fatigue, but a state of depletion of attentional and emotional resources.”

Digital technology overloads the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

As the 'context switch' is repeated, the brain has to redistribute energy as if it were starting a new task each time.

For example, every time we switch tasks, such as checking email, then replying to a messenger message, then attending a meeting, then checking social media again, our brain experiences high energy consumption.

If this process is repeated, the brain can easily fall into a 'fog' state.

In particular, push notifications on smartphones, real-time response requests on messengers, and algorithmic recommendations on websites continuously stimulate the brain's dopamine circuits.

By repeatedly responding to immediate rewards, the brain becomes constantly on the move in search of stronger stimuli, which ultimately leads to a breakdown in concentration and emotional exhaustion.

The author emphasizes that to address chronic digital fatigue, we must reestablish our relationship with digital tools.

Dozens of pop-up alarms, a deluge of options, requests for responses everywhere…

How to Break Free from Digital Burnout and Reclaim a Balanced Lifestyle

《Digital Detox》 presents eight practical rules for this.

These rules are not simply about moderation, but are based on strategic design to create habits that don't tire while coexisting with digital technology.

For example, 'Rule 1: Cut Your Tools in Half' highlights that simply reducing the number of digital tools you use in your daily life can reduce fatigue by up to 40%.

Rather than blindly using less, it is a method that helps you make choices so that you only keep the tools you really need.

Rule 2: Match Media to Information advises determining which collaboration tools best suit your goals.

Choosing the right tool for your purpose, whether it's speed or accuracy, is key to saving energy.

'Rule 5: Don't Assume' reminds us not to judge others based on their DMs or emojis, and shows how misunderstandings in digital spaces drain our emotional energy faster.

Also, 'Rule 6: Act with Intention' suggests that before using a tool, you should first decide 'why you are using it' and 'how much you will use it'.

This kind of intentional use is effective in increasing immersion and satisfaction.

Part 3 presents coping strategies in organizations and at home.

In particular, the author has been working as an advisor to technology companies such as Google and Microsoft, researching organizational solutions to digital fatigue.

Based on his experience in advising global companies, he provides more practical application methods.

It also includes advice for parents raising digital natives and how to use AI technology wisely.

Additionally, the appendix includes a framework for digital detox that can be applied directly to your daily life.

Office workers, creatives, managers, parents, and others who feel distracted will learn how to build a healthier relationship with digital tools in their daily lives through this book.

Scientific diagnosis and solutions for those who can't put their smartphones down 24 hours a day!

In today's world, where digital tools prioritizing convenience and efficiency have become ubiquitous, have our lives truly improved? Paul Leonardi, a professor of technology management at the University of California and author of "Digital Detox," has spent the past two decades researching the impact of digital technology on the human body and mind.

The authors specifically surveyed 12 countries on the question, “How tired do you feel when using digital technology?” and found that the average fatigue score rose significantly from 2.6 in 2002 to 5.5 in 2022.

This isn't just general work-related stress; it's a clear sign that digital technology is directly taxing the human brain and emotional circuitry.

He defines this state as “not simply fatigue, but a state of depletion of attentional and emotional resources.”

Digital technology overloads the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

As the 'context switch' is repeated, the brain has to redistribute energy as if it were starting a new task each time.

For example, every time we switch tasks, such as checking email, then replying to a messenger message, then attending a meeting, then checking social media again, our brain experiences high energy consumption.

If this process is repeated, the brain can easily fall into a 'fog' state.

In particular, push notifications on smartphones, real-time response requests on messengers, and algorithmic recommendations on websites continuously stimulate the brain's dopamine circuits.

By repeatedly responding to immediate rewards, the brain becomes constantly on the move in search of stronger stimuli, which ultimately leads to a breakdown in concentration and emotional exhaustion.

The author emphasizes that to address chronic digital fatigue, we must reestablish our relationship with digital tools.

Dozens of pop-up alarms, a deluge of options, requests for responses everywhere…

How to Break Free from Digital Burnout and Reclaim a Balanced Lifestyle

《Digital Detox》 presents eight practical rules for this.

These rules are not simply about moderation, but are based on strategic design to create habits that don't tire while coexisting with digital technology.

For example, 'Rule 1: Cut Your Tools in Half' highlights that simply reducing the number of digital tools you use in your daily life can reduce fatigue by up to 40%.

Rather than blindly using less, it is a method that helps you make choices so that you only keep the tools you really need.

Rule 2: Match Media to Information advises determining which collaboration tools best suit your goals.

Choosing the right tool for your purpose, whether it's speed or accuracy, is key to saving energy.

'Rule 5: Don't Assume' reminds us not to judge others based on their DMs or emojis, and shows how misunderstandings in digital spaces drain our emotional energy faster.

Also, 'Rule 6: Act with Intention' suggests that before using a tool, you should first decide 'why you are using it' and 'how much you will use it'.

This kind of intentional use is effective in increasing immersion and satisfaction.

Part 3 presents coping strategies in organizations and at home.

In particular, the author has been working as an advisor to technology companies such as Google and Microsoft, researching organizational solutions to digital fatigue.

Based on his experience in advising global companies, he provides more practical application methods.

It also includes advice for parents raising digital natives and how to use AI technology wisely.

Additionally, the appendix includes a framework for digital detox that can be applied directly to your daily life.

Office workers, creatives, managers, parents, and others who feel distracted will learn how to build a healthier relationship with digital tools in their daily lives through this book.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: December 5, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 396 pages | 560g | 145*215*25mm

- ISBN13: 9791140716494

- ISBN10: 1140716492

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)