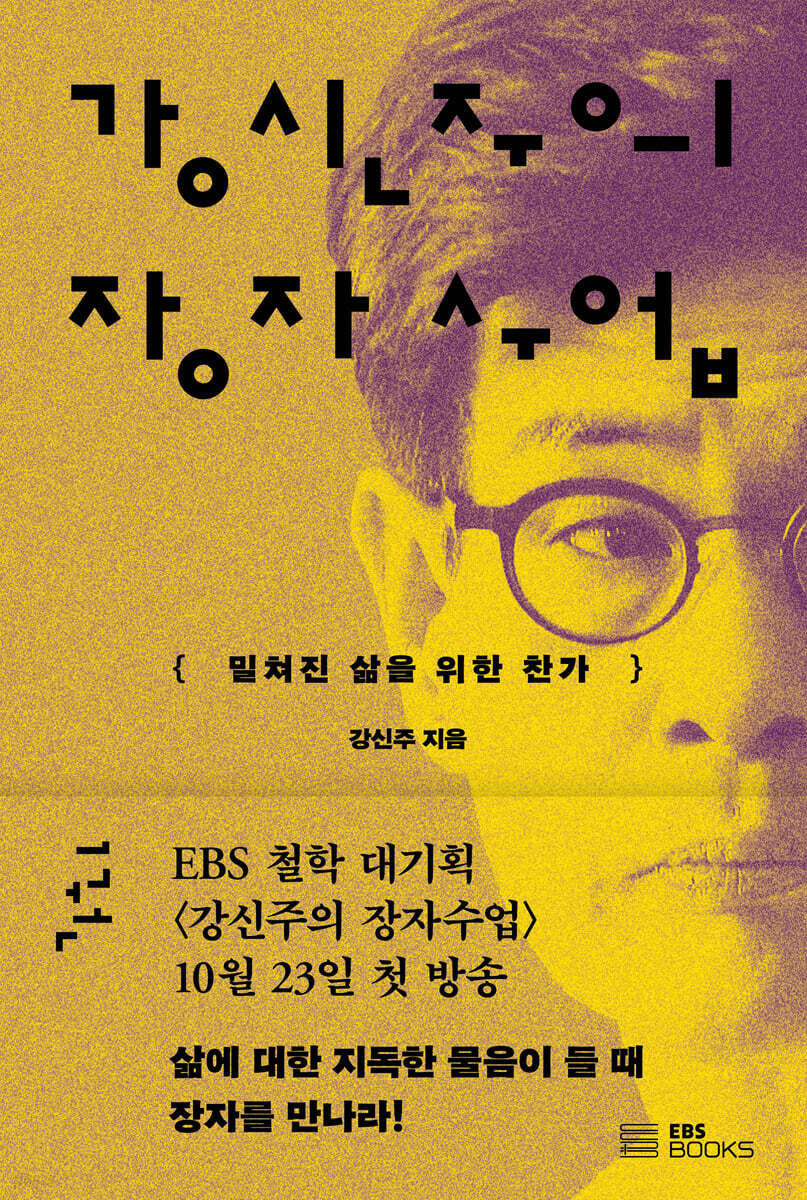

Kang Shin-ju's Lesson 1

|

Description

Book Introduction

Simultaneous publication and broadcast of EBS's philosophy project "Kang Shin-ju's Jangja Lessons" The last book by Kang Shin-ju, the most beloved philosopher of our time The most powerful interpretation of Zhuangzi in 2,500 years “When you have a serious question about life, meet Zhuangzi!” In an age of overuse and competition, the 2,500-year-old teachings of Zhuangzi are offered to a Korean society weary of competition. Philosopher Kang Shin-ju received his doctorate in 『Zhuangzi』 in his youth, and after contemplating Zhuangzi's thoughts for over 20 years, he published several books on Zhuangzi. The reason he once again chose 『Zhuangzi』 as a philosophical book that is absolutely necessary for our times is because 『Zhuangzi』 is the most powerful text that can help all of us living in an age of excess use regain positivity and self-esteem in life. Philosopher Kang Shin-ju defines Zhuangzi from three main perspectives. Zhuangzi is the 'philosopher of uselessness'. 2,500 years ago, China's Warring States Period (403 BC - 221 BC) was a time when everyone proved their usefulness and existence under the slogan of enriching the country and strengthening the military. In an era when the logic of talent was prevalent, Zhuangzi was the only one to advocate the 'philosophy of uselessness'. Zhuangzi is a ‘philosopher of others.’ Zhuangzi was the first in the East to discover the 'other' and to ponder the relationship with the other. Finally, Jangja is a 'contextualist'. We were wary of ‘allism’ and ‘absolutism’ and realized that the world is not one but is made up of diverse and complex contexts. 『Kang Shin-ju's Jangja Lessons』 (2 volumes) focuses on these three perspectives and travels across the 2,500-year Warring States period and 21st-century Korean society, awakening us to the seriousness of how a world obsessed with cost-effectiveness and utility is eating away at us. Furthermore, based on the core philosophy of Zhuangzi, it strongly pumps and pulses the power to regain our self-esteem and sovereignty over our lives. This book will be published and broadcast simultaneously with the EBS broadcast program “Kang Shin-ju’s Jangja Class” (scheduled to air on October 23, 2023). This is the first major EBS philosophy project in 10 years, following “Lao-tzu and the 21st Century” (1999, Kim Yong-ok) and “Modern Philosopher, Lao-tzu” (2013, Choi Jin-seok). |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

[Volume 1]

In publishing the book

Prologue_ The wind is blowing, it's time to ride on the back of the great eagle.

Part 1 Jumping over the ground

1 Hymn to Philosophy - Tales of the Underworld

2 How to Prevent Love Tragedy - The Seabird Story

3. Take your life! - The Empty Ship Story

The Wind Blows, So I Must Live! - The Tale of the Great Bong

5 The Power of the Small Man, the Authority of the Small Man - The Story of Yunpyeon

6 Useless Good Day - The Story of a Giant Tree

7 Vanity, Too Fatal to Be Loved - A Beauty Story

8 The World is Not One - The Story of Son Yak

Dancing with the 9th Batters - The Story of Pojeong

10 The Sound of the Wind in the Empty Sky - The Story of the Wind

11 Dreaming of a Free Community - The Story of Your Teacher

12 Nothing is Universal - A Poem

Part 2: Going Against the Wave

13 Beyond Good and Evil - A Story of Hypocrisy

14 What a Colorful World! - A Story of the Heart

15 Secrets to Leisure and Confidence - Private Life Stories

16 Crossing the Law of Causality - Shadow Stories

17 Living a Life of Freedom - A Story of Jiriso

18 A Longing for God and the Soul - Jinjae's Story

19 What the Elder Sees in the Wilderness - The Story of the Holy Spirit

20 A New Life Where Body and Mind Intersect - A Drunkard's Story

21 Right here, don't go any further! - One Story

Tune in to the 22nd batter - Sim Jae's story

23 The Deep Swamp of Metaphysics - A Story of Argument

24. This is how Yeolja lived! - The Story of Yeolja

In publishing the book

Prologue_ The wind is blowing, it's time to ride on the back of the great eagle.

Part 1 Jumping over the ground

1 Hymn to Philosophy - Tales of the Underworld

2 How to Prevent Love Tragedy - The Seabird Story

3. Take your life! - The Empty Ship Story

The Wind Blows, So I Must Live! - The Tale of the Great Bong

5 The Power of the Small Man, the Authority of the Small Man - The Story of Yunpyeon

6 Useless Good Day - The Story of a Giant Tree

7 Vanity, Too Fatal to Be Loved - A Beauty Story

8 The World is Not One - The Story of Son Yak

Dancing with the 9th Batters - The Story of Pojeong

10 The Sound of the Wind in the Empty Sky - The Story of the Wind

11 Dreaming of a Free Community - The Story of Your Teacher

12 Nothing is Universal - A Poem

Part 2: Going Against the Wave

13 Beyond Good and Evil - A Story of Hypocrisy

14 What a Colorful World! - A Story of the Heart

15 Secrets to Leisure and Confidence - Private Life Stories

16 Crossing the Law of Causality - Shadow Stories

17 Living a Life of Freedom - A Story of Jiriso

18 A Longing for God and the Soul - Jinjae's Story

19 What the Elder Sees in the Wilderness - The Story of the Holy Spirit

20 A New Life Where Body and Mind Intersect - A Drunkard's Story

21 Right here, don't go any further! - One Story

Tune in to the 22nd batter - Sim Jae's story

23 The Deep Swamp of Metaphysics - A Story of Argument

24. This is how Yeolja lived! - The Story of Yeolja

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

Over 2,500 years ago, Zhuangzi of East Asia was not simply one of the Chinese philosophers or one of the Hundred Schools of Thought.

(…) He shows us that the values we spend our entire lives trying to obtain are not only worthless but also harmful to our lives.

(…) Zhuangzi’s insight is that all the commonly accepted values, the values we cling to, are merely variations on the ‘carrot and stick’ logic.

--- p.5~6, from “Publishing a Book”

Let's vehemently reject becoming a talent, someone useful to the system! Let's fully enjoy our own desires, not those of others! Let's not seek justice, whether in the grand scheme of things—nation or society, or in the small, like our company or family—and if we don't like it, let's coolly leave! This is why the "Zhuangzi" remains anti-establishment and revolutionary, even 2,500 years ago, and why it remains a book for our lives, not a textbook for the system.

--- p.14, from “Prologue”

People, past and present, tend to evaluate things based on their usefulness.

Even as a child, the question I heard most often was, “If I do that, will I get rice or cooked rice?”

(…) The same was true during the Warring States Period in China (403 BC – 221 BC) about 2,500 years ago.

It was a time when survival and competition were the top priorities for individuals, societies, and nations.

In this respect, the slogan “A rich nation and a strong military” is symbolic.

How can we make a nation wealthy and a strong military? This logic applies equally to individuals.

How can individuals become wealthy and powerful?

--- p.27~28, from “Hymn to Philosophy - Tales of the Underworld”

Let's say a person gets on someone else's boat and crosses the Yellow River.

If another ship were to accidentally collide with this one, who would be more upset: the owner or the people who got on board? It would probably be the owner, who feels the urge to "this is my ship."

Consider also the case of inter-floor noise.

Even if they live in the same house, who would be more sensitive to noise between floors: a renter or an owner? If they have similar personalities, the homeowner is likely to be more sensitive.

(…) This all has to do with the age-old human prejudice that what I have defines me, or in other words, that I am what I have and what I have is me.

--- p.56, from "Have Fun! Your Life - The Story of an Empty Ship"

We must make a decision.

Will I break through this narrow world? Or will I shrink myself and adapt to it?

(…) That’s why wind is important.

Because the wind is a symbol of a bigger world, a symbol of others outside our narrow world.

Gon dreams of a bigger world through the wind, and Bung wants to ride the wind to go to a bigger world.

It's about choosing a world that suits your size.

--- p.73~74, from "The Wind Blows, So I Must Live! - The Tale of the Great Bong"

The elder brother smiles brightly in front of them and says,

Aren't you mistakenly thinking that the world is a round cylinder and that if you push it, you'll fall and die? And aren't you taking your own lives because you foresee destruction?

The eldest son speaks of hope with a smile.

The edge of the cylinder is not a cliff, and the outside is not a precipice either.

When you look from the land where you are standing, the distant sea seems to drop off like a cliff, but when you go there yourself, it seems like there is no such thing as a cliff or precipice.

--- p.119, from “The World is Not One - The Story of Hand Medicine”

Without learning from others, or without 'being with' and forming relationships with others, life and experience are impossible.

Manual workers know very well that they cannot do their jobs properly if they do not respect others.

Whether it be other people, cows, trees, fish, iron, titanium, land or water.

On the other hand, mental labor captured in the world of command and obedience has difficulty properly relating to others encountered in the world of life.

Because others who are objects of domination and control cannot become companions in our lives.

--- p.134, from “Dancing with the Others - The Story of Pojeong”

If there is no wind noise, that is fine, but if there is wind noise, that sound necessarily presupposes 'a certain hole' and 'a certain wind'.

And even when the two meet, they don't all make the same sound.

The shapes of the holes vary, and the winds are also plural in speed and direction.

Depending on the shape of the hole and the strength and direction of the wind, each produces its own unique wind sound.

--- p.151, from “The Sound of the Wind in the Empty Sky - The Story of the Wind”

The key words to understand Zhangzi's thoughts are 'other' and 'context'.

Of course, Jangja does not conceptualize and use this keyword.

In fact, these two keywords were first conceptualized and thematically addressed in the late 20th century.

This is probably why the storybook called "Zhuangzi" still doesn't seem outdated.

Already 2,500 years ago, Zhuangzi pondered the other and the context to a degree that rivaled even modern Western philosophers.

--- p.189, from “Beyond Good and Evil - A Story of Hypocrisy”

During the Warring States Period, as barbarism, disguised as civilization, intensified and expanded in an irresistible trend on the Chinese mainland, philosophers who confronted it head-on emerged.

It was the eldest son.

(…) Through his short but powerful story of life and death, Zhuangzi dreamed of a human being who could resist domestication, a human being who resolutely refused to be tamed by rewards and punishments, a human being who enjoyed freedom as much as a wild horse or a wolf.

--- p.223, from “The Secret of Leisure and Confidence - Private Life Stories”

Sincerity can be interpreted as ‘a fulfilled heart.’

(…) The settler mind, that is, the sincerity, comes with a strong desire to possess my home, my land, and further, what is mine.

On the other hand, nomads leave their current place without hesitation if they don't like it.

(…) It is the insight that if there is no sincerity, there is no right or wrong, or that a settled life creates right or wrong.

--- p.279~286, from “What Jangja Saw in the Gwangmakjiya - The Story of the Sacred Heart”

Now, the last piece of advice from the master comes into view.

“Do not go further than this, just follow this (無適焉, 因是已)” This is a story about not going beyond the full situation where you feel that “nothing in the world is bigger than the tip of an autumn hair,” the sorrowful situation where you feel that “no one in the world lives longer than a child who died young,” and the wondrous situation where you feel that “the world was born with me,” but rather following this situation.

--- p.314, from "Right Here, Don't Go Any Further! - One Story"

The will to freedom, to neither dominate nor obey others, or the will to love, to support others rather than rely on them, are the principles of the “undisturbed” Liezi.

(…) The word ‘consistency’ may be the fate that those who have emptied their hearts must endure.

If Zarathustra spoke thus, then this is how Liezi lived.

(…) He shows us that the values we spend our entire lives trying to obtain are not only worthless but also harmful to our lives.

(…) Zhuangzi’s insight is that all the commonly accepted values, the values we cling to, are merely variations on the ‘carrot and stick’ logic.

--- p.5~6, from “Publishing a Book”

Let's vehemently reject becoming a talent, someone useful to the system! Let's fully enjoy our own desires, not those of others! Let's not seek justice, whether in the grand scheme of things—nation or society, or in the small, like our company or family—and if we don't like it, let's coolly leave! This is why the "Zhuangzi" remains anti-establishment and revolutionary, even 2,500 years ago, and why it remains a book for our lives, not a textbook for the system.

--- p.14, from “Prologue”

People, past and present, tend to evaluate things based on their usefulness.

Even as a child, the question I heard most often was, “If I do that, will I get rice or cooked rice?”

(…) The same was true during the Warring States Period in China (403 BC – 221 BC) about 2,500 years ago.

It was a time when survival and competition were the top priorities for individuals, societies, and nations.

In this respect, the slogan “A rich nation and a strong military” is symbolic.

How can we make a nation wealthy and a strong military? This logic applies equally to individuals.

How can individuals become wealthy and powerful?

--- p.27~28, from “Hymn to Philosophy - Tales of the Underworld”

Let's say a person gets on someone else's boat and crosses the Yellow River.

If another ship were to accidentally collide with this one, who would be more upset: the owner or the people who got on board? It would probably be the owner, who feels the urge to "this is my ship."

Consider also the case of inter-floor noise.

Even if they live in the same house, who would be more sensitive to noise between floors: a renter or an owner? If they have similar personalities, the homeowner is likely to be more sensitive.

(…) This all has to do with the age-old human prejudice that what I have defines me, or in other words, that I am what I have and what I have is me.

--- p.56, from "Have Fun! Your Life - The Story of an Empty Ship"

We must make a decision.

Will I break through this narrow world? Or will I shrink myself and adapt to it?

(…) That’s why wind is important.

Because the wind is a symbol of a bigger world, a symbol of others outside our narrow world.

Gon dreams of a bigger world through the wind, and Bung wants to ride the wind to go to a bigger world.

It's about choosing a world that suits your size.

--- p.73~74, from "The Wind Blows, So I Must Live! - The Tale of the Great Bong"

The elder brother smiles brightly in front of them and says,

Aren't you mistakenly thinking that the world is a round cylinder and that if you push it, you'll fall and die? And aren't you taking your own lives because you foresee destruction?

The eldest son speaks of hope with a smile.

The edge of the cylinder is not a cliff, and the outside is not a precipice either.

When you look from the land where you are standing, the distant sea seems to drop off like a cliff, but when you go there yourself, it seems like there is no such thing as a cliff or precipice.

--- p.119, from “The World is Not One - The Story of Hand Medicine”

Without learning from others, or without 'being with' and forming relationships with others, life and experience are impossible.

Manual workers know very well that they cannot do their jobs properly if they do not respect others.

Whether it be other people, cows, trees, fish, iron, titanium, land or water.

On the other hand, mental labor captured in the world of command and obedience has difficulty properly relating to others encountered in the world of life.

Because others who are objects of domination and control cannot become companions in our lives.

--- p.134, from “Dancing with the Others - The Story of Pojeong”

If there is no wind noise, that is fine, but if there is wind noise, that sound necessarily presupposes 'a certain hole' and 'a certain wind'.

And even when the two meet, they don't all make the same sound.

The shapes of the holes vary, and the winds are also plural in speed and direction.

Depending on the shape of the hole and the strength and direction of the wind, each produces its own unique wind sound.

--- p.151, from “The Sound of the Wind in the Empty Sky - The Story of the Wind”

The key words to understand Zhangzi's thoughts are 'other' and 'context'.

Of course, Jangja does not conceptualize and use this keyword.

In fact, these two keywords were first conceptualized and thematically addressed in the late 20th century.

This is probably why the storybook called "Zhuangzi" still doesn't seem outdated.

Already 2,500 years ago, Zhuangzi pondered the other and the context to a degree that rivaled even modern Western philosophers.

--- p.189, from “Beyond Good and Evil - A Story of Hypocrisy”

During the Warring States Period, as barbarism, disguised as civilization, intensified and expanded in an irresistible trend on the Chinese mainland, philosophers who confronted it head-on emerged.

It was the eldest son.

(…) Through his short but powerful story of life and death, Zhuangzi dreamed of a human being who could resist domestication, a human being who resolutely refused to be tamed by rewards and punishments, a human being who enjoyed freedom as much as a wild horse or a wolf.

--- p.223, from “The Secret of Leisure and Confidence - Private Life Stories”

Sincerity can be interpreted as ‘a fulfilled heart.’

(…) The settler mind, that is, the sincerity, comes with a strong desire to possess my home, my land, and further, what is mine.

On the other hand, nomads leave their current place without hesitation if they don't like it.

(…) It is the insight that if there is no sincerity, there is no right or wrong, or that a settled life creates right or wrong.

--- p.279~286, from “What Jangja Saw in the Gwangmakjiya - The Story of the Sacred Heart”

Now, the last piece of advice from the master comes into view.

“Do not go further than this, just follow this (無適焉, 因是已)” This is a story about not going beyond the full situation where you feel that “nothing in the world is bigger than the tip of an autumn hair,” the sorrowful situation where you feel that “no one in the world lives longer than a child who died young,” and the wondrous situation where you feel that “the world was born with me,” but rather following this situation.

--- p.314, from "Right Here, Don't Go Any Further! - One Story"

The will to freedom, to neither dominate nor obey others, or the will to love, to support others rather than rely on them, are the principles of the “undisturbed” Liezi.

(…) The word ‘consistency’ may be the fate that those who have emptied their hearts must endure.

If Zarathustra spoke thus, then this is how Liezi lived.

--- p.355~357, from "This is how Yeolja lived! - The Story of Yeolja"

Publisher's Review

Will I take the path that is useful to others, or will I take the path that is useful to myself?

The Warring States Period, in which Zhang Zi lived, was a time of fierce competition.

To win the competition, monarchs were obsessed with recruiting talented people, promising honor, power, and wealth to those who would become their talents.

In such a situation, the disciples of the Hundred Schools of Thought argued that if one followed their own teachings, one could survive the fierce competition for survival.

This book says that the word 'road' or 'Tao' appeared right here.

If we look at the logic of talent from 2,500 years ago, it is similar to our lives as we enter the competitive logic of the 21st century.

The author says that the 'logic of competition and talent' is a powerful ideology that is still valid in both the era of Zhangzi and the present.

No, the author points out that during the Warring States period, the logic was limited to the ruling class, but today it applies to everyone, so it can be said to have expanded.

Zhuangzi was a philosopher who questioned the logic of usefulness and talent in the Warring States period and tried to overcome it.

He argued that usefulness can actually destroy our lives, while uselessness can enrich our lives.

Above all, the author says that useful reason is nothing more than reason demanded by the state or capital.

The reason why we can earn more money and rise to a higher position is because it is for the country and capital, and it cannot be truly for me or for humanity.

The author poses the question to us through the thoughts of Zhuangzi from 2,500 years ago: "Should I take the path that is useful to others?" or "Should I take the path that is useful to myself?"

This book selects 48 stories from the original text of Zhuangzi that are essential for our times and, through powerful interpretations, brings Zhuangzi face-to-face with our lives in the 21st century.

This book helps those who go out every day to prove their worth, driven by the compulsion that they will lose their value if they cannot prove their worth to the company, the country, capital, and even their family, regain their positivity and self-esteem.

Our lives are incomplete without meeting others.

Zhuangzi was a philosopher who pondered over others and relationships with others.

The author defines such a person in one word as a ‘philosopher of others.’

Through the concept of 'others', Zhuangzi also directly criticizes Confucius, the idol of the time.

Regarding Confucius' famous saying, "Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself (己所不欲 勿施於人)", Zhuangzi asks, "But can what I want be the same as what others want?"

We know very well that there are very few relationships in which the other person wants what we want and the other person does not want what we do not want.

Rather, there are countless cases where the other person does not want what I want, and I do not want what the other person wants.

So, Zhuangzi says that if you love someone, true love is giving them what they want.

And the author says that if we take Zhuangzi's advice, our lives can be completely changed.

All the relationships surrounding me, such as mother, father, husband, wife, daughter, son, senior, junior, etc., can move toward love rather than destruction.

What does it mean to encounter another? Does it mean we meet physically? This book borrows from Spinoza's Ethics to explain that encountering another evokes two emotions: joy and sorrow.

If you don't feel joy or sorrow when you meet someone, then you can't really say that you've 'met' them.

We meet countless people on the subway, at work, and in restaurants, but we don't meet them.

But what if, when we return home and see our husbands, wives, and children, we feel no emotion? Then perhaps we're not truly connecting.

When I empty myself, I can encounter others.

So how can we encounter others? The author uses Zhuangzi's famous line, "I have lost myself," to discuss the possibility of encountering others.

To empty oneself, to lose oneself, means to eliminate the possessiveness and self-consciousness within oneself.

For example, when the thoughts and self-consciousness that fill my mind, such as 'I am smart', 'I am a man (woman)', 'I have a lot of money', 'I am sexy', etc. disappear, the possibility arises that others can take their place.

The author explains the vague concept of Osang-ah using the metaphor of the sound of the wind.

The sounds we hear, such as ‘the sound of the wind,’ ‘the sound of flowing water,’ and ‘the sound of breathing,’ arise from the encounter with something.

A sound is made when a ‘certain hole’ and a ‘certain wind’ meet.

So, who came from this sound of encounter? Was it the wind? Or the hole? The answer is both.

If the hole is blocked, the wind cannot blow and if the hole is empty, the wind cannot blow and the sound cannot be heard.

It is only when these two meet that a sound is made.

The author says:

All birth and change, including ours, are the result of this encounter.

But if I were like a bamboo shoot, full of possessiveness and self-consciousness, what kind of wind, what kind of other could possibly pass me by? That's why I'm Osang-ah.

Sometimes we become an empty hole, and sometimes we become the wind. We must put the other person in that hole or enter the other person's hole in order to meet and communicate.

Context is not just one thing

The author lists two key words for viewing the book: ‘other’ and ‘context.’

The world that Jang-ja sees is not singular but plural, and rather than an all-ism that says, "This is the only principle," he thinks, "The world is full of diverse and complex contexts."

On the contrary, all attention was paid to the day.

Because all attention only destroys our singularity and closes the hole of the other that was opened to us.

In the book, the author describes the unification of context as 'context singularism' and the diversity of context as 'context pluralism'.

Just as the Warring States period 2,500 years ago, when wealth, military power, and personal success were absolute principles, and personal achievement and personal fame have become absolute beliefs in the 21st century capitalist era, our lives are also far from the contextual pluralism that Zhuangzi spoke of.

The author has felt the seriousness of this issue vividly while living as a philosopher.

If we believe that the world where the logic of usefulness prevails is the only world, then the moment we consider ourselves useless in that world, we cannot help but despair.

Therefore, the contextual pluralism of Jangja can give us hope.

If you feel useless in the current context, it is wise to tell yourself to create another context in which you can be useful.

The author says:

It's not that usefulness is important, nor is it that dance is important.

It is more important to affirm our lives and find a context for a better direction.

The Warring States Period, in which Zhang Zi lived, was a time of fierce competition.

To win the competition, monarchs were obsessed with recruiting talented people, promising honor, power, and wealth to those who would become their talents.

In such a situation, the disciples of the Hundred Schools of Thought argued that if one followed their own teachings, one could survive the fierce competition for survival.

This book says that the word 'road' or 'Tao' appeared right here.

If we look at the logic of talent from 2,500 years ago, it is similar to our lives as we enter the competitive logic of the 21st century.

The author says that the 'logic of competition and talent' is a powerful ideology that is still valid in both the era of Zhangzi and the present.

No, the author points out that during the Warring States period, the logic was limited to the ruling class, but today it applies to everyone, so it can be said to have expanded.

Zhuangzi was a philosopher who questioned the logic of usefulness and talent in the Warring States period and tried to overcome it.

He argued that usefulness can actually destroy our lives, while uselessness can enrich our lives.

Above all, the author says that useful reason is nothing more than reason demanded by the state or capital.

The reason why we can earn more money and rise to a higher position is because it is for the country and capital, and it cannot be truly for me or for humanity.

The author poses the question to us through the thoughts of Zhuangzi from 2,500 years ago: "Should I take the path that is useful to others?" or "Should I take the path that is useful to myself?"

This book selects 48 stories from the original text of Zhuangzi that are essential for our times and, through powerful interpretations, brings Zhuangzi face-to-face with our lives in the 21st century.

This book helps those who go out every day to prove their worth, driven by the compulsion that they will lose their value if they cannot prove their worth to the company, the country, capital, and even their family, regain their positivity and self-esteem.

Our lives are incomplete without meeting others.

Zhuangzi was a philosopher who pondered over others and relationships with others.

The author defines such a person in one word as a ‘philosopher of others.’

Through the concept of 'others', Zhuangzi also directly criticizes Confucius, the idol of the time.

Regarding Confucius' famous saying, "Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself (己所不欲 勿施於人)", Zhuangzi asks, "But can what I want be the same as what others want?"

We know very well that there are very few relationships in which the other person wants what we want and the other person does not want what we do not want.

Rather, there are countless cases where the other person does not want what I want, and I do not want what the other person wants.

So, Zhuangzi says that if you love someone, true love is giving them what they want.

And the author says that if we take Zhuangzi's advice, our lives can be completely changed.

All the relationships surrounding me, such as mother, father, husband, wife, daughter, son, senior, junior, etc., can move toward love rather than destruction.

What does it mean to encounter another? Does it mean we meet physically? This book borrows from Spinoza's Ethics to explain that encountering another evokes two emotions: joy and sorrow.

If you don't feel joy or sorrow when you meet someone, then you can't really say that you've 'met' them.

We meet countless people on the subway, at work, and in restaurants, but we don't meet them.

But what if, when we return home and see our husbands, wives, and children, we feel no emotion? Then perhaps we're not truly connecting.

When I empty myself, I can encounter others.

So how can we encounter others? The author uses Zhuangzi's famous line, "I have lost myself," to discuss the possibility of encountering others.

To empty oneself, to lose oneself, means to eliminate the possessiveness and self-consciousness within oneself.

For example, when the thoughts and self-consciousness that fill my mind, such as 'I am smart', 'I am a man (woman)', 'I have a lot of money', 'I am sexy', etc. disappear, the possibility arises that others can take their place.

The author explains the vague concept of Osang-ah using the metaphor of the sound of the wind.

The sounds we hear, such as ‘the sound of the wind,’ ‘the sound of flowing water,’ and ‘the sound of breathing,’ arise from the encounter with something.

A sound is made when a ‘certain hole’ and a ‘certain wind’ meet.

So, who came from this sound of encounter? Was it the wind? Or the hole? The answer is both.

If the hole is blocked, the wind cannot blow and if the hole is empty, the wind cannot blow and the sound cannot be heard.

It is only when these two meet that a sound is made.

The author says:

All birth and change, including ours, are the result of this encounter.

But if I were like a bamboo shoot, full of possessiveness and self-consciousness, what kind of wind, what kind of other could possibly pass me by? That's why I'm Osang-ah.

Sometimes we become an empty hole, and sometimes we become the wind. We must put the other person in that hole or enter the other person's hole in order to meet and communicate.

Context is not just one thing

The author lists two key words for viewing the book: ‘other’ and ‘context.’

The world that Jang-ja sees is not singular but plural, and rather than an all-ism that says, "This is the only principle," he thinks, "The world is full of diverse and complex contexts."

On the contrary, all attention was paid to the day.

Because all attention only destroys our singularity and closes the hole of the other that was opened to us.

In the book, the author describes the unification of context as 'context singularism' and the diversity of context as 'context pluralism'.

Just as the Warring States period 2,500 years ago, when wealth, military power, and personal success were absolute principles, and personal achievement and personal fame have become absolute beliefs in the 21st century capitalist era, our lives are also far from the contextual pluralism that Zhuangzi spoke of.

The author has felt the seriousness of this issue vividly while living as a philosopher.

If we believe that the world where the logic of usefulness prevails is the only world, then the moment we consider ourselves useless in that world, we cannot help but despair.

Therefore, the contextual pluralism of Jangja can give us hope.

If you feel useless in the current context, it is wise to tell yourself to create another context in which you can be useful.

The author says:

It's not that usefulness is important, nor is it that dance is important.

It is more important to affirm our lives and find a context for a better direction.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 20, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 360 pages | 584g | 146*217*22mm

- ISBN13: 9788954799454

- ISBN10: 8954799450

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)