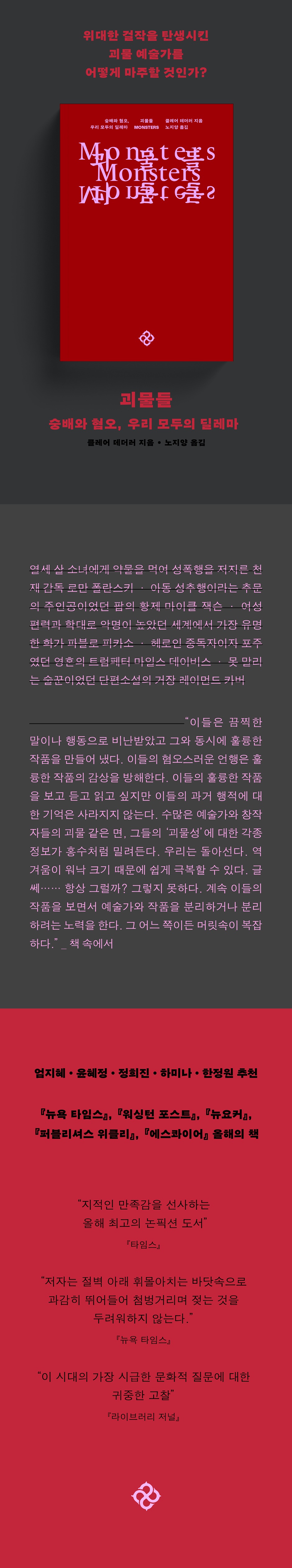

monsters

|

Description

Book Introduction

“A monster artist who created a great masterpiece

How will we face it?”

Recommended by Uhm Ji-hye, Yoon Hye-jeong, Jeong Hee-jin, Ha Mi-na, and Han Jeong-won

Book of the Year from The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Publisher's Weekly, and Esquire

In November 2017, an essay published in The Paris Review set social media and the internet ablaze.

The title of the essay is "How should we deal with the art of monstrous men?"

The dictionary definition of a monster is something frightening, something huge, or something associated with success (a box office monster), but for the author of this essay, a monster is “a person whose actions prevent us from understanding a work of art for what it is.”

These kinds of debates have always been around, but 2017 was a special year.

This is because the global 'MeToo movement' was triggered by Hollywood's biggest film producer, Harvey Weinstein.

Author Claire Dederer talks to people.

Would you like to talk about this topic together?

This is how the book 『Monsters: Worship and Loathing, Our Common Dilemma』, which expands on the questions raised in this essay, came into the world.

How will we face it?”

Recommended by Uhm Ji-hye, Yoon Hye-jeong, Jeong Hee-jin, Ha Mi-na, and Han Jeong-won

Book of the Year from The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Publisher's Weekly, and Esquire

In November 2017, an essay published in The Paris Review set social media and the internet ablaze.

The title of the essay is "How should we deal with the art of monstrous men?"

The dictionary definition of a monster is something frightening, something huge, or something associated with success (a box office monster), but for the author of this essay, a monster is “a person whose actions prevent us from understanding a work of art for what it is.”

These kinds of debates have always been around, but 2017 was a special year.

This is because the global 'MeToo movement' was triggered by Hollywood's biggest film producer, Harvey Weinstein.

Author Claire Dederer talks to people.

Would you like to talk about this topic together?

This is how the book 『Monsters: Worship and Loathing, Our Common Dilemma』, which expands on the questions raised in this essay, came into the world.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

prolog

1st roll call.

Woody Allen

2 stains.

Michael Jackson

3 fans.

JK

Rolling

4 critics

5 geniuses.

Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway

6 Anti-Semitism, racism, and the question of time.

Richard Wagner, Virginia Woolf, Willa Cather

7 Anti-Monsters.

Vladimir Nabokov

8 Those who silence and those who are silenced.

Carl Andre, Ana Mendieta

9 Am I a monster?

10 Mothers who abandoned their children.

Doris Lessing, Joni Mitchell

11 Female Lazarus.

Valerie Solanas, Sylvia Plath

12 Drinkers.

Raymond Carver

13 Beloved.

Miles Davis

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

1st roll call.

Woody Allen

2 stains.

Michael Jackson

3 fans.

JK

Rolling

4 critics

5 geniuses.

Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway

6 Anti-Semitism, racism, and the question of time.

Richard Wagner, Virginia Woolf, Willa Cather

7 Anti-Monsters.

Vladimir Nabokov

8 Those who silence and those who are silenced.

Carl Andre, Ana Mendieta

9 Am I a monster?

10 Mothers who abandoned their children.

Doris Lessing, Joni Mitchell

11 Female Lazarus.

Valerie Solanas, Sylvia Plath

12 Drinkers.

Raymond Carver

13 Beloved.

Miles Davis

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Detailed image

Into the book

I remember exactly the day it all started.

One rainy spring day in 2014, I found myself waging a lonely war, a war of my imagination, against a terrifyingly terrifying genius.

At the time, I was researching a man named Roman Polanski for a book I was writing, and I was so shocked by his brutality that I couldn't come to my senses for a moment.

It was truly monumental.

It was so overwhelming in scale, like the Grand Canyon, and the valley was so deep that it was a bit bewildering.

March 10, 1977? I'm writing this date by heart. Roman Polanski brought Samantha Gailey to his friend Jack Nicholson's Hollywood Hills home.

He took Samantha to the jacuzzi, made her undress, and fed her Quaalude.

After a while, he went to the sofa where Samantha was sitting and inserted himself into her vagina, then turned her over and inserted himself into her anus before ejaculating.

After synthesizing all these details, one very simple fact remains:

A thirteen-year-old girl was anally raped.

--- From the "Prologue"

Men say they want to know why Woody Allen upsets women so much.

Ultimately, a great work of art is something that makes us feel something, so isn't it my freedom to feel something or not?

But when I say I was a little annoyed by Manhattan, men say,

“Except for that feeling.

“That’s the wrong feeling,” he says with authority.

Manhattan is truly a masterpiece of genius.

But who can say that? Authorities say a work must remain pure, untainted by the author's life.

Authorities say that the autobiography is in error.

Authority believes that a work of art exists in an ideal state (a place that transcends history, a high mountain, a snowy field, purity).

Authority tells us to ignore the emotions that naturally arise when we know the creator's history and past.

Authority laughs at such things.

The authority claims that the work can be appreciated without regard to autobiography or history.

Authority sides with male producers.

Not the audience.

--- 「Name 1.

From "Woody Allen"

What I want to say through all this realization is this:

I ask this question again.

How should we approach the works of these monster men? At this point, I cannot approach this question as an impartial observer.

I am not a person whose history has been erased.

I was sexually assaulted by a middle-aged man when I was a teenager.

I was also sexually harassed.

I was bullied on the street.

I was caught, dragged away, and escaped attempted rape.

I'm not recounting this experience to say that I'm a special person.

I want to say that I am not special.

Like so many women, or most women, I have personal issues with this issue.

So when I ask how I should approach the works of these monster men, I cannot help but feel compassion for their victims.

I too have been in the same or similar position as them.

I remember what that monster did to me.

We cannot approach this issue with a cold, detached attitude.

I sympathize with those accusers.

I am also a whistleblower.

But even so, I still want to consume art.

Because before all this, I am human.

--- From "4 Critics"

Isn't this what a female monster looks like? Abandoning a child.

It's always like that.

The female monster is Doris Lessing, who leaves her two children and moves to London to live the life of a writer.

The female monster is Sylvia Plath, who committed suicide.

It was horrible enough that they committed suicide, but they also taped off the children's rooms to prevent gas from entering.

Let's not even mention the bread and milk I gave my children before I died.

The incident itself is a terrifying poem.

She even had a dream where she devoured a man as if she were swallowing air.

But no matter what, the reason she has to be a monster is because she made the children motherless.

--- From "9 Am I a Monster?"

When we ask, “What are we going to do with the art of these monster men?” we force ourselves into the role of fixed consumers.

Passing the burden of the problem onto the consumer is how capitalism works.

Consumers don't always prioritize ethics.

Once a series of decisions have been made, you have to figure out how to respond and interpret for yourself what is the right and ethical behavior.

Even as Michael Jackson's behavior became increasingly bizarre, he was still being used, packaged, supplied, catered to, and made to taste.

The music industry doesn't care about ethics when it comes to musicians.

The job is left to us.

When 'I Want You Back' comes on in a cafe, we are swept up in a whirlwind of emotions and reactions.

--- "12 Drinkers.

From "Raymond Carver"

What do we do with the terrible people in our lives? Most of the time, we continue to love them.

The reason family is such a burden is because they are monsters (and angels and everything in between) that we have been forced to take care of.

They are monsters we did not choose.

If you think about it, is there anything in the world so random? And yet, somehow, we continue to love our families, and we end up loving them.

As a child, I believed in human perfection.

The people I love have to be perfect, and I have to be perfect too.

But that's not how love works.

--- 「13 Beloved Ones.

From "Miles Davis"

I think this book is a good example of a very human criticism, a living, breathing criticism.

As the author confesses in the text, “For me, the most profound joy of reading comes mainly from subjective writing,” he puts aside authority and objectivity and sometimes with difficulty brings out his own fluttering emotions and deeply hidden voice.

One rainy spring day in 2014, I found myself waging a lonely war, a war of my imagination, against a terrifyingly terrifying genius.

At the time, I was researching a man named Roman Polanski for a book I was writing, and I was so shocked by his brutality that I couldn't come to my senses for a moment.

It was truly monumental.

It was so overwhelming in scale, like the Grand Canyon, and the valley was so deep that it was a bit bewildering.

March 10, 1977? I'm writing this date by heart. Roman Polanski brought Samantha Gailey to his friend Jack Nicholson's Hollywood Hills home.

He took Samantha to the jacuzzi, made her undress, and fed her Quaalude.

After a while, he went to the sofa where Samantha was sitting and inserted himself into her vagina, then turned her over and inserted himself into her anus before ejaculating.

After synthesizing all these details, one very simple fact remains:

A thirteen-year-old girl was anally raped.

--- From the "Prologue"

Men say they want to know why Woody Allen upsets women so much.

Ultimately, a great work of art is something that makes us feel something, so isn't it my freedom to feel something or not?

But when I say I was a little annoyed by Manhattan, men say,

“Except for that feeling.

“That’s the wrong feeling,” he says with authority.

Manhattan is truly a masterpiece of genius.

But who can say that? Authorities say a work must remain pure, untainted by the author's life.

Authorities say that the autobiography is in error.

Authority believes that a work of art exists in an ideal state (a place that transcends history, a high mountain, a snowy field, purity).

Authority tells us to ignore the emotions that naturally arise when we know the creator's history and past.

Authority laughs at such things.

The authority claims that the work can be appreciated without regard to autobiography or history.

Authority sides with male producers.

Not the audience.

--- 「Name 1.

From "Woody Allen"

What I want to say through all this realization is this:

I ask this question again.

How should we approach the works of these monster men? At this point, I cannot approach this question as an impartial observer.

I am not a person whose history has been erased.

I was sexually assaulted by a middle-aged man when I was a teenager.

I was also sexually harassed.

I was bullied on the street.

I was caught, dragged away, and escaped attempted rape.

I'm not recounting this experience to say that I'm a special person.

I want to say that I am not special.

Like so many women, or most women, I have personal issues with this issue.

So when I ask how I should approach the works of these monster men, I cannot help but feel compassion for their victims.

I too have been in the same or similar position as them.

I remember what that monster did to me.

We cannot approach this issue with a cold, detached attitude.

I sympathize with those accusers.

I am also a whistleblower.

But even so, I still want to consume art.

Because before all this, I am human.

--- From "4 Critics"

Isn't this what a female monster looks like? Abandoning a child.

It's always like that.

The female monster is Doris Lessing, who leaves her two children and moves to London to live the life of a writer.

The female monster is Sylvia Plath, who committed suicide.

It was horrible enough that they committed suicide, but they also taped off the children's rooms to prevent gas from entering.

Let's not even mention the bread and milk I gave my children before I died.

The incident itself is a terrifying poem.

She even had a dream where she devoured a man as if she were swallowing air.

But no matter what, the reason she has to be a monster is because she made the children motherless.

--- From "9 Am I a Monster?"

When we ask, “What are we going to do with the art of these monster men?” we force ourselves into the role of fixed consumers.

Passing the burden of the problem onto the consumer is how capitalism works.

Consumers don't always prioritize ethics.

Once a series of decisions have been made, you have to figure out how to respond and interpret for yourself what is the right and ethical behavior.

Even as Michael Jackson's behavior became increasingly bizarre, he was still being used, packaged, supplied, catered to, and made to taste.

The music industry doesn't care about ethics when it comes to musicians.

The job is left to us.

When 'I Want You Back' comes on in a cafe, we are swept up in a whirlwind of emotions and reactions.

--- "12 Drinkers.

From "Raymond Carver"

What do we do with the terrible people in our lives? Most of the time, we continue to love them.

The reason family is such a burden is because they are monsters (and angels and everything in between) that we have been forced to take care of.

They are monsters we did not choose.

If you think about it, is there anything in the world so random? And yet, somehow, we continue to love our families, and we end up loving them.

As a child, I believed in human perfection.

The people I love have to be perfect, and I have to be perfect too.

But that's not how love works.

--- 「13 Beloved Ones.

From "Miles Davis"

I think this book is a good example of a very human criticism, a living, breathing criticism.

As the author confesses in the text, “For me, the most profound joy of reading comes mainly from subjective writing,” he puts aside authority and objectivity and sometimes with difficulty brings out his own fluttering emotions and deeply hidden voice.

--- From the Translator's Note

Publisher's Review

Monsters scattered around us,

The deepening dilemma of fans

What do Roman Polanski, Michael Jackson, Pablo Picasso, Miles Davis, and Hemingway have in common?

The point is that they are artists who have achieved great success in their respective fields.

These are naturally followed by adjectives like ‘best’, ‘genius’, and ‘world-class’.

The second thing they have in common? They were all at the center of a scandal.

They were artists who created great works, but they were also sexual predators, abusers, drug addicts, and pimps.

While any human being can have many faces, we often use the expression "monstrous" to describe those who evoke polar opposite emotions of admiration and disgust.

Monsters are everywhere.

The film "Tar" vividly shows us the monsters that could be around us.

Lydia Tarr, the world's greatest conductor with overwhelming charisma, is a monster not only in terms of skill but also in how she uses her position as a means to satisfy her personal desires.

This work, which calmly follows her decline from the pinnacle of life, makes the audience think about the separation between art and the artist's life.

The New York Times Magazine recently published an article addressing the controversy surrounding a documentary about the singer Prince.

The conflict between the production team, who wanted to show Prince, a figure who left his mark on American pop history, without any editing, and the Prince Foundation, which is desperately trying to block the broadcast, claiming that the girlfriend's testimony that Prince assaulted her is false, is a clear example of what a "monster" looks like in our society, and on the other hand, it makes us think about how we should deal with a monster artist with revealed moral flaws.

With the development of social media, the boundaries between personal lives are becoming blurred, and we are now able to observe the stars we have always admired from a much closer distance than before.

The more this happens, the deeper the dilemma becomes.

You've built a deep sense of intimacy and trust by following a star, peering into their daily lives. But what if they one day turn out to be a criminal? Would unfollowing them be enough to resolve the issue? What if even after unfollowing, they, their work, and their traces linger in your mind? "Monsters" confronts head-on the dilemma between monsters and the audience who consume their creations.

The question of whether the work and its creator should be separated is a long-standing debate, but while there have been numerous attempts to hear and compare the opinions of both sides, there has been no result in which a single author has become a party to the dilemma and persistently delves into the subject, which is a welcome achievement.

Book of the Year selected by leading media outlets

From Roman Polanski to Joni Mitchell—Geniuses Who Became Monsters

Author Claire Dederer is an art enthusiast who explores film, music, art, and books to explore the dilemmas we face in our daily lives in a candid and intelligent way.

As the New York Times reviewed, this book, which is “part thesis, part memoir, and part everything else,” was named a “book of the year” by major American media outlets, receiving praise such as “the year’s most intellectually satisfying nonfiction book” (Times) and “a valuable reflection on the most pressing cultural questions of our time” (Library Journal).

It all started with Roman Polanski.

He is a genius film director who directed films such as “Disgust,” “The Satanic Verses,” and “Chinatown.” Cinephiles around the world, including author Dederer, praise his film aesthetics.

But in his private life, he is a child molester who drugged and sexually assaulted a thirteen-year-old girl.

This gap also created a rift in the hearts of fans.

I love his movies so much, but knowing this, I can't enjoy them as much as I want.

Our conscience hinders us.

The gap between reality, which we thought was limited to private sorrow and dilemma, has become a realm of collective anger with the 'MeToo' movement.

This is how the author's journey began.

Monsters don't discriminate between genders.

If male monsters are generally depicted as heinous criminals, female monsters are generally associated with 'motherhood'.

When a woman is deemed to lack the maternal love that society considers normal, such as abandoning or neglecting a child, she becomes a monster.

As a feminist writer, the author questions this too.

The moment when the standard of 'motherhood' is so easily turned into 'monsters' by Doris Lessing, who left her children behind and became a successful writer, and Joni Mitchell, who gave her baby up for adoption, the part where women in the arts reflect on where they should stand has great implications for our society.

A book that shines with the author's efforts to weave a dense web of thought.

As an essay, the most brilliant part of this book is the part where the author looks into his own 'monstrousness'.

Rather than simply typifying monstrosity, Dederer seeks to look at the 'monster' within herself as a writer and mother.

The author, too, is not free from ‘motherhood.’

I ask myself if my work would be better if I were more selfish (pursuing ambitions like a man, ignoring the stroller in the hallway, closing the door with my back to the children, etc.).

I wonder if I failed as a writer because I didn't aspire to greater selfishness.

The author's willingness to remain true to his own feelings and to acknowledge the duality and contradictions within himself is what has enabled this book to garner the sympathy and support of so many.

‘Emotion’ is also an important keyword that runs through this book.

“How should we treat the work of a monster artist?” may seem like a philosophical question at first glance, but for the author it is an emotional question, and that emotion is ultimately love.

We say we 'consume' art, but in fact, it would be more accurate to add the modifier 'emotional' before that.

Because art is something that goes beyond the commodities of a consumer society and directly interacts with our emotions.

At this point, the author's question expands to:

"What should we do about the monstrous people we 'love'?" This book shines with the author's history of enjoying and loving various forms of art, and his effort to nimbly weave a dense web of thought by nimbly catching the thoughts and questions that arise from time to time.

The deepening dilemma of fans

What do Roman Polanski, Michael Jackson, Pablo Picasso, Miles Davis, and Hemingway have in common?

The point is that they are artists who have achieved great success in their respective fields.

These are naturally followed by adjectives like ‘best’, ‘genius’, and ‘world-class’.

The second thing they have in common? They were all at the center of a scandal.

They were artists who created great works, but they were also sexual predators, abusers, drug addicts, and pimps.

While any human being can have many faces, we often use the expression "monstrous" to describe those who evoke polar opposite emotions of admiration and disgust.

Monsters are everywhere.

The film "Tar" vividly shows us the monsters that could be around us.

Lydia Tarr, the world's greatest conductor with overwhelming charisma, is a monster not only in terms of skill but also in how she uses her position as a means to satisfy her personal desires.

This work, which calmly follows her decline from the pinnacle of life, makes the audience think about the separation between art and the artist's life.

The New York Times Magazine recently published an article addressing the controversy surrounding a documentary about the singer Prince.

The conflict between the production team, who wanted to show Prince, a figure who left his mark on American pop history, without any editing, and the Prince Foundation, which is desperately trying to block the broadcast, claiming that the girlfriend's testimony that Prince assaulted her is false, is a clear example of what a "monster" looks like in our society, and on the other hand, it makes us think about how we should deal with a monster artist with revealed moral flaws.

With the development of social media, the boundaries between personal lives are becoming blurred, and we are now able to observe the stars we have always admired from a much closer distance than before.

The more this happens, the deeper the dilemma becomes.

You've built a deep sense of intimacy and trust by following a star, peering into their daily lives. But what if they one day turn out to be a criminal? Would unfollowing them be enough to resolve the issue? What if even after unfollowing, they, their work, and their traces linger in your mind? "Monsters" confronts head-on the dilemma between monsters and the audience who consume their creations.

The question of whether the work and its creator should be separated is a long-standing debate, but while there have been numerous attempts to hear and compare the opinions of both sides, there has been no result in which a single author has become a party to the dilemma and persistently delves into the subject, which is a welcome achievement.

Book of the Year selected by leading media outlets

From Roman Polanski to Joni Mitchell—Geniuses Who Became Monsters

Author Claire Dederer is an art enthusiast who explores film, music, art, and books to explore the dilemmas we face in our daily lives in a candid and intelligent way.

As the New York Times reviewed, this book, which is “part thesis, part memoir, and part everything else,” was named a “book of the year” by major American media outlets, receiving praise such as “the year’s most intellectually satisfying nonfiction book” (Times) and “a valuable reflection on the most pressing cultural questions of our time” (Library Journal).

It all started with Roman Polanski.

He is a genius film director who directed films such as “Disgust,” “The Satanic Verses,” and “Chinatown.” Cinephiles around the world, including author Dederer, praise his film aesthetics.

But in his private life, he is a child molester who drugged and sexually assaulted a thirteen-year-old girl.

This gap also created a rift in the hearts of fans.

I love his movies so much, but knowing this, I can't enjoy them as much as I want.

Our conscience hinders us.

The gap between reality, which we thought was limited to private sorrow and dilemma, has become a realm of collective anger with the 'MeToo' movement.

This is how the author's journey began.

Monsters don't discriminate between genders.

If male monsters are generally depicted as heinous criminals, female monsters are generally associated with 'motherhood'.

When a woman is deemed to lack the maternal love that society considers normal, such as abandoning or neglecting a child, she becomes a monster.

As a feminist writer, the author questions this too.

The moment when the standard of 'motherhood' is so easily turned into 'monsters' by Doris Lessing, who left her children behind and became a successful writer, and Joni Mitchell, who gave her baby up for adoption, the part where women in the arts reflect on where they should stand has great implications for our society.

A book that shines with the author's efforts to weave a dense web of thought.

As an essay, the most brilliant part of this book is the part where the author looks into his own 'monstrousness'.

Rather than simply typifying monstrosity, Dederer seeks to look at the 'monster' within herself as a writer and mother.

The author, too, is not free from ‘motherhood.’

I ask myself if my work would be better if I were more selfish (pursuing ambitions like a man, ignoring the stroller in the hallway, closing the door with my back to the children, etc.).

I wonder if I failed as a writer because I didn't aspire to greater selfishness.

The author's willingness to remain true to his own feelings and to acknowledge the duality and contradictions within himself is what has enabled this book to garner the sympathy and support of so many.

‘Emotion’ is also an important keyword that runs through this book.

“How should we treat the work of a monster artist?” may seem like a philosophical question at first glance, but for the author it is an emotional question, and that emotion is ultimately love.

We say we 'consume' art, but in fact, it would be more accurate to add the modifier 'emotional' before that.

Because art is something that goes beyond the commodities of a consumer society and directly interacts with our emotions.

At this point, the author's question expands to:

"What should we do about the monstrous people we 'love'?" This book shines with the author's history of enjoying and loving various forms of art, and his effort to nimbly weave a dense web of thought by nimbly catching the thoughts and questions that arise from time to time.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 30, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 340 pages | 376g | 128*190*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788932475233

- ISBN 10: 8932475237

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)