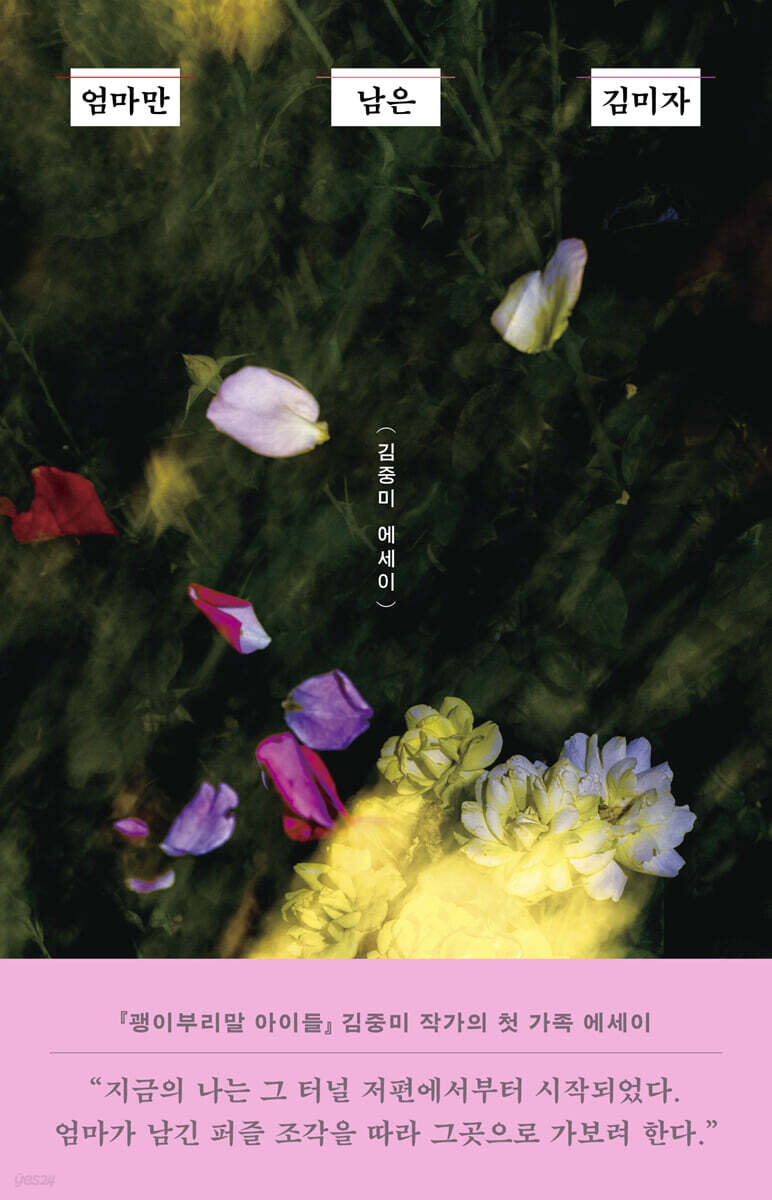

Kim Mi-ja, who is left with only her mother

|

Description

Book Introduction

Kim Jung-mi's first family essay, "The Children of the Magpie Beak"

“The me of today started from the other side of that tunnel.

“I’m trying to get there by following the puzzle pieces my mother left behind.”

Beginning with "The Children of the Magpie" in 2000, author Kim Jung-mi has consistently shown diverse aspects of society to children and adolescents through literature, offering empathy and comfort. Now, she tells her own intimate family story for the first time.

The author unravels the story of her family, beginning in the 1970s, while caring for her mother, who has cognitive impairment.

The story begins with the author's original family and spreads to the next generation, capturing the lives of those who have been forced to the margins as Korean society has developed over the past 50 years.

In a story that begins with care for the elderly within a family, the author takes a fresh look at the time spent by women in that era.

Just as the writer's life is connected to the mother's time, the mother's life is also connected to the maternal grandmother's time.

The landscape encompasses not only the female narrative, but also the lives of men who inevitably influence each other, the relationship between fathers and daughters, the author's concerns about the roles of wife and mother as she builds a family within the community after starting the slum movement, and even her reflections on art at the time.

By the end of the essay, readers will have looked back at the society that has deeply permeated our daily lives and the places we stand from with a different perspective.

“When readers encounter transparent writing that even reveals the internal organs, they are pierced.

“My heart fluttered throughout the reading, as if it were threaded through the text.” _Reporter and writer Lee Moon-young

“The me of today started from the other side of that tunnel.

“I’m trying to get there by following the puzzle pieces my mother left behind.”

Beginning with "The Children of the Magpie" in 2000, author Kim Jung-mi has consistently shown diverse aspects of society to children and adolescents through literature, offering empathy and comfort. Now, she tells her own intimate family story for the first time.

The author unravels the story of her family, beginning in the 1970s, while caring for her mother, who has cognitive impairment.

The story begins with the author's original family and spreads to the next generation, capturing the lives of those who have been forced to the margins as Korean society has developed over the past 50 years.

In a story that begins with care for the elderly within a family, the author takes a fresh look at the time spent by women in that era.

Just as the writer's life is connected to the mother's time, the mother's life is also connected to the maternal grandmother's time.

The landscape encompasses not only the female narrative, but also the lives of men who inevitably influence each other, the relationship between fathers and daughters, the author's concerns about the roles of wife and mother as she builds a family within the community after starting the slum movement, and even her reflections on art at the time.

By the end of the essay, readers will have looked back at the society that has deeply permeated our daily lives and the places we stand from with a different perspective.

“When readers encounter transparent writing that even reveals the internal organs, they are pierced.

“My heart fluttered throughout the reading, as if it were threaded through the text.” _Reporter and writer Lee Moon-young

index

Prologue | Mom, Who Am I?

Poverty is powerless, but love is, really?

Mother's letter

Father's Broken Wing

Grandma's table where anyone could come

My grandmother asked.

What is Central America's dream?

Kim Mi-ja, who is left with only her mother

A grain of rice chases away ten ghosts

Poverty didn't even allow my mother neighbors.

That care saved me

The Pandemic Reveals the Reality of Elder Care

Between my daughter's tuition and the Paul Mauriat Orchestra's concert in Korea

Your mom and dad loved you so passionately

Somewhere between love and hate and respect

Dad, thank you for waiting.

Breaking free from the eldest daughter complex and taking a new path

The days in Dongducheon where I felt and learned

Sister, can we sleep holding hands?

A pretty useful defense mechanism, I'm a strong kid.

The comfort and strength that the art I dreamed of gave me

What was your mother's dream?

Mom's sheep are strawberries and pears in a cold box

Why did I become a task-oriented mom?

Am I the only one here?

Epilogue | A Happy Life Can't Be Achieved Alone

Author's Note

Poverty is powerless, but love is, really?

Mother's letter

Father's Broken Wing

Grandma's table where anyone could come

My grandmother asked.

What is Central America's dream?

Kim Mi-ja, who is left with only her mother

A grain of rice chases away ten ghosts

Poverty didn't even allow my mother neighbors.

That care saved me

The Pandemic Reveals the Reality of Elder Care

Between my daughter's tuition and the Paul Mauriat Orchestra's concert in Korea

Your mom and dad loved you so passionately

Somewhere between love and hate and respect

Dad, thank you for waiting.

Breaking free from the eldest daughter complex and taking a new path

The days in Dongducheon where I felt and learned

Sister, can we sleep holding hands?

A pretty useful defense mechanism, I'm a strong kid.

The comfort and strength that the art I dreamed of gave me

What was your mother's dream?

Mom's sheep are strawberries and pears in a cold box

Why did I become a task-oriented mom?

Am I the only one here?

Epilogue | A Happy Life Can't Be Achieved Alone

Author's Note

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

Who I am today is the result of the time I have lived through, as well as the time my mother Kim Mi-ja, father Kim Chang-sam, maternal grandmother Choi Eo-jin, and paternal grandmother Jeong Ok-saeng have lived through.

It took courage to refine the time of my mother and the time of my father, who had lost the opportunity to speak in language.

--- p.29

I remember going to Shinpo Market with my grandmother and the merchants slowly avoiding her.

Grandma knew at a glance which crabs and fish were the best among those on display at the market stalls.

Whether the merchant quoted a high or low price, the grandmother paid the price you set and bought it.

If the merchant quoted too cheaply, he would give more money, saying, "Can you make a living like that?" If he quoted too expensively, he would yell at him and call him a thief.

--- p.52

The regulars at Grandma's outdoor cafe were diverse, including men pulling carts or carrying containers at Incheon Port, women who served customers at clubs all night, and merchants and elderly people doing business in Gwandong.

The grandmother even invited strangers passing by on the street to coffee.

Coffee wasn't the only thing Grandma shared.

In Gwandong, near Incheon Port, there were as many wandering people as permanent residents.

For those people, the time they spent sitting on the bench in front of the rice shop once in the morning and feeling the presence of others must have been more energizing than a cup of coffee.

--- pp.69-70

That day my grandmother asked me.

“What is Central America’s dream?”

It was a very embarrassing question.

At that time, no one asked me about my dream.

(…) I thought it would be better to quickly erase dreams that could not be achieved from life.

--- p.88

Even while my mother was losing her memory alone in the villa living room, I only thought about my own life.

(…) It was sad for Kim Mi-ja, who only had ‘Mom’ as her identity, as her mother had lost all her memories.

--- p.95

Although I lived in a different era than my mother, I still treated cooking as a trivial task.

But that 'food' bound the young people gathered in the study room together as a community.

So, like my mother, I couldn't give up that food.

It took a long time for the community to share a meal together.

Eating together is a precious medium that connects us to each other.

But the problem was that cooking rice was always the woman's job.

--- p.111

"Why is Mom Dad's? Mom is just Kim Mi-ja."

--- p.185

It would have been nice to push me down even further since I was already at a low point.

There were people there that I liked and that I would come to love.

--- p.253

The way the people have lived for a long time.

But now it is disappearing or being forgotten, and so it is a way that we want to protect even more desperately.

The way our mothers and grandmothers lost it during the Japanese colonial period and war, and spent their entire lives trying to reconnect it.

To restore that way of life in reality, a place for living, a community, was needed.

--- p.355

My mother taught me through life that a happy life cannot be achieved alone.

From my mother and grandmother, I learned how to respect others, how to be by their side, and how to live a happy life of service, consideration, and sharing.

So I was able to go out into the world without being confined within my family.

The adults around me showed me what community is like.

It took courage to refine the time of my mother and the time of my father, who had lost the opportunity to speak in language.

--- p.29

I remember going to Shinpo Market with my grandmother and the merchants slowly avoiding her.

Grandma knew at a glance which crabs and fish were the best among those on display at the market stalls.

Whether the merchant quoted a high or low price, the grandmother paid the price you set and bought it.

If the merchant quoted too cheaply, he would give more money, saying, "Can you make a living like that?" If he quoted too expensively, he would yell at him and call him a thief.

--- p.52

The regulars at Grandma's outdoor cafe were diverse, including men pulling carts or carrying containers at Incheon Port, women who served customers at clubs all night, and merchants and elderly people doing business in Gwandong.

The grandmother even invited strangers passing by on the street to coffee.

Coffee wasn't the only thing Grandma shared.

In Gwandong, near Incheon Port, there were as many wandering people as permanent residents.

For those people, the time they spent sitting on the bench in front of the rice shop once in the morning and feeling the presence of others must have been more energizing than a cup of coffee.

--- pp.69-70

That day my grandmother asked me.

“What is Central America’s dream?”

It was a very embarrassing question.

At that time, no one asked me about my dream.

(…) I thought it would be better to quickly erase dreams that could not be achieved from life.

--- p.88

Even while my mother was losing her memory alone in the villa living room, I only thought about my own life.

(…) It was sad for Kim Mi-ja, who only had ‘Mom’ as her identity, as her mother had lost all her memories.

--- p.95

Although I lived in a different era than my mother, I still treated cooking as a trivial task.

But that 'food' bound the young people gathered in the study room together as a community.

So, like my mother, I couldn't give up that food.

It took a long time for the community to share a meal together.

Eating together is a precious medium that connects us to each other.

But the problem was that cooking rice was always the woman's job.

--- p.111

"Why is Mom Dad's? Mom is just Kim Mi-ja."

--- p.185

It would have been nice to push me down even further since I was already at a low point.

There were people there that I liked and that I would come to love.

--- p.253

The way the people have lived for a long time.

But now it is disappearing or being forgotten, and so it is a way that we want to protect even more desperately.

The way our mothers and grandmothers lost it during the Japanese colonial period and war, and spent their entire lives trying to reconnect it.

To restore that way of life in reality, a place for living, a community, was needed.

--- p.355

My mother taught me through life that a happy life cannot be achieved alone.

From my mother and grandmother, I learned how to respect others, how to be by their side, and how to live a happy life of service, consideration, and sharing.

So I was able to go out into the world without being confined within my family.

The adults around me showed me what community is like.

--- p.402

Publisher's Review

Standing with the poor in a world that encourages us to have more

Confessions of author Kim Jung-mi, who has personally become a networker.

Kim Jung-mi, who chose voluntary poverty and started 'A Room Next to the Railroad' in Manseok-dong, Incheon in 1987, then 'Study Room Next to the Railroad' in 1988, and 'Small School Next to the Railroad' in Ganghwa in 2001, has published a new family essay, 'Kim Mi-ja, Who Only Has a Mother Left Behind.'

Following the essay 『The More Flowers, the Better』, which deals with community activities, and the youth essay 『How to Remember Friends』, which focuses on friendship, this is the first time that a piece containing the author's own family story has been published.

Manseok-dong's old name, 'Gwangiburimal', is a place where refugees gathered after the Korean War and homeless people gathered during the industrialization period to form a village.

The author published the children's book "The Children of the Magpie" based on his life in Manseok-dong, which became the first children's book to sell over 2 million copies, illuminating many people with the structural problems of poverty.

The author thought it was wrong to use the royalties from a book that was made known through broadcasting for personal use, so he used them to help the Community Chest of Korea, local movements, labor movement groups and individuals, and young people in private study rooms who needed tuition.

The author's writing has always captured the dark and lower levels of society.

In a world that encourages us to have more, where does the author's inspiration come from, who has personally connected the poor with his life, preventing them from being isolated?

The author has lived in a community for a long time and has met mothers who have lived difficult lives, bound by the shackles of patriarchy, and who have to be the breadwinners of their families as daughters and the eldest sons.

At the same time, he was “shocked by the family system that is not a family that helps each other, but rather a family that becomes a trap for each other.”

The author confesses, “I never imagined that I, someone like myself, would write a ‘family story,’” and sets out to find the times that made me who I am today.

“Poverty was familiar to my mother, but loneliness was unfamiliar.

“Mom had to go to the turtle market to meet someone she knew.”

The essay begins with the author's recent story of caring for her mother, who has cognitive impairment.

When the writer encounters Kim Mi-ja, who has lost all her memories but never forgot the fact that she is a mother, and is left with only a 'mother', he begins to wonder about Kim Mi-ja, who is not a 'mother'.

The author, who has done her best as a child simply by enduring the poverty of her family, gains a new understanding of her mother through the stories of her siblings and relatives.

In the past, poverty was something my mother was rather familiar with, and more than that, she was someone who could not stand the social isolation that came with poverty.

The neighborhood I went to in search of cheaper monthly rent had a regular change of people, and since my mother was also in a situation where she had to leave again, I couldn't even maintain social relationships like neighbors.

The author learned in Dongducheon, where he spent his childhood, that socially vulnerable people must band together to survive in this harsh world.

At that time, the neighborhood women only protected my child and did not like people who tried to feed him more.

If there was a child in the neighborhood who was not attending school, we looked into the situation, reported it to the town office, and collected clothes from home and gave them to them.

At the time, when beggars who were called lepers came to beg, my mother would not let them use the word leprosy, which was a derogatory term for Hansen's disease, and in a time when not even a ten-won coin was used carelessly, she would give the beggars a hundred-won bill.

It was also my mother who introduced me to poet Han Ha-un's poem 'Jeolla-do Road'.

The porch of the Dongducheon house was a place where neighborhood housewives and middle and high school students would constantly stay to look for their mothers.

As they moved to Incheon due to the constant job losses, the author's parents became nothing more than Mr. Kim and the restaurant owner.

In the city, my mother was a shabby person, wearing a rubber skirt and a worn-out shirt, and in the factory housing, there were no neighbors with whom she could cry and laugh.

The alleys where people met disappeared due to redevelopment and high-rise buildings, and the village could not exist in the vertical passageways.

My mother, who had been shrinking from the unfamiliar loneliness, left the company house and went to Songnim-dong, a mountain village similar to Dongducheon, where she gradually made acquaintances.

The author, who had just graduated from high school and started working, recalls that after a hard day's work, he would climb up to that mountain village and for some reason, his tension would ease and he would feel relaxed.

Since then, we moved every two years in the mountain village, and my mother always chose a place that wasn't too far from the turtle market.

Because I had to go there to meet someone I knew.

“It would have been nice if you had pushed me down even further since I was already at a low point.

“There were people there that I was compatible with, people I would come to love.”

When the author was diagnosed with depression and her mother's cognitive impairment, she felt guilty for having to turn away from her mother, who sat alone in a dark room.

Kim Mi-ja, who doesn't know that the person in front of her is her daughter, says that she likes nursing homes because she remembers that she was someone's mother.

It's not just because I don't have to cook, but because it's a place where there are people to build relationships with, a place where there's 'me' in addition to my mom.

The author says that the fact that her maternal grandmother, aunt, and mother all suffered from severe cognitive impairment may not be genetic, but rather “a heartbreaking legacy from the journeys they have lived.”

Discovering an individual who had been obscured by social roles directs the author's gaze to older generations of women.

Kim Mi-ja's story leads to the life of her mother, Choi Eo-jin, and her father, Kim Chang-sam's story leads to the life of his mother, Jeong Ok-saeng.

My maternal grandmother, who tried to live as a new woman, was the one who asked the author, “What is your dream in Central America?” at a time when no one asked about dreams, and my paternal grandmother, who was sold as a daughter-in-law, was like a big tree who readily prepared a meal for anyone who looked hungry.

The adults around him each lived different lives, but they all shared the experience that "even if you don't have much, sharing what you have makes you happy."

Experience becomes reality, and its repetition becomes belief, which is naturally embodied in the body and mind.

Beliefs that cannot be easily forgotten become actions, become someone's life, and change the world little by little.

The 40-year-long struggle for the poor was not a difficult but grand task for the writer.

It is a daily routine that we must learn by seeing and doing.

In his essays, the author also reveals moments when the community experienced a crisis.

When faced with each other's differences and the roots of the community are shaken, the author simply chooses to remain shaken.

“If Auntie goes somewhere, can’t you leave the lights on in the study room?” asked the children who had stayed on the road until night, waiting for their parents who had gone to work.

“Even when we’re out playing at night, I feel safe when the lights in the study room are on.” At those words, the author promises, “The lights in the study room will never go out, and I will wait there, just like my mom did.”

The author's journey of seeking a lower place through life rather than words itself makes us reflect on what kind of warmth and shame we should share with society.

Confessions of author Kim Jung-mi, who has personally become a networker.

Kim Jung-mi, who chose voluntary poverty and started 'A Room Next to the Railroad' in Manseok-dong, Incheon in 1987, then 'Study Room Next to the Railroad' in 1988, and 'Small School Next to the Railroad' in Ganghwa in 2001, has published a new family essay, 'Kim Mi-ja, Who Only Has a Mother Left Behind.'

Following the essay 『The More Flowers, the Better』, which deals with community activities, and the youth essay 『How to Remember Friends』, which focuses on friendship, this is the first time that a piece containing the author's own family story has been published.

Manseok-dong's old name, 'Gwangiburimal', is a place where refugees gathered after the Korean War and homeless people gathered during the industrialization period to form a village.

The author published the children's book "The Children of the Magpie" based on his life in Manseok-dong, which became the first children's book to sell over 2 million copies, illuminating many people with the structural problems of poverty.

The author thought it was wrong to use the royalties from a book that was made known through broadcasting for personal use, so he used them to help the Community Chest of Korea, local movements, labor movement groups and individuals, and young people in private study rooms who needed tuition.

The author's writing has always captured the dark and lower levels of society.

In a world that encourages us to have more, where does the author's inspiration come from, who has personally connected the poor with his life, preventing them from being isolated?

The author has lived in a community for a long time and has met mothers who have lived difficult lives, bound by the shackles of patriarchy, and who have to be the breadwinners of their families as daughters and the eldest sons.

At the same time, he was “shocked by the family system that is not a family that helps each other, but rather a family that becomes a trap for each other.”

The author confesses, “I never imagined that I, someone like myself, would write a ‘family story,’” and sets out to find the times that made me who I am today.

“Poverty was familiar to my mother, but loneliness was unfamiliar.

“Mom had to go to the turtle market to meet someone she knew.”

The essay begins with the author's recent story of caring for her mother, who has cognitive impairment.

When the writer encounters Kim Mi-ja, who has lost all her memories but never forgot the fact that she is a mother, and is left with only a 'mother', he begins to wonder about Kim Mi-ja, who is not a 'mother'.

The author, who has done her best as a child simply by enduring the poverty of her family, gains a new understanding of her mother through the stories of her siblings and relatives.

In the past, poverty was something my mother was rather familiar with, and more than that, she was someone who could not stand the social isolation that came with poverty.

The neighborhood I went to in search of cheaper monthly rent had a regular change of people, and since my mother was also in a situation where she had to leave again, I couldn't even maintain social relationships like neighbors.

The author learned in Dongducheon, where he spent his childhood, that socially vulnerable people must band together to survive in this harsh world.

At that time, the neighborhood women only protected my child and did not like people who tried to feed him more.

If there was a child in the neighborhood who was not attending school, we looked into the situation, reported it to the town office, and collected clothes from home and gave them to them.

At the time, when beggars who were called lepers came to beg, my mother would not let them use the word leprosy, which was a derogatory term for Hansen's disease, and in a time when not even a ten-won coin was used carelessly, she would give the beggars a hundred-won bill.

It was also my mother who introduced me to poet Han Ha-un's poem 'Jeolla-do Road'.

The porch of the Dongducheon house was a place where neighborhood housewives and middle and high school students would constantly stay to look for their mothers.

As they moved to Incheon due to the constant job losses, the author's parents became nothing more than Mr. Kim and the restaurant owner.

In the city, my mother was a shabby person, wearing a rubber skirt and a worn-out shirt, and in the factory housing, there were no neighbors with whom she could cry and laugh.

The alleys where people met disappeared due to redevelopment and high-rise buildings, and the village could not exist in the vertical passageways.

My mother, who had been shrinking from the unfamiliar loneliness, left the company house and went to Songnim-dong, a mountain village similar to Dongducheon, where she gradually made acquaintances.

The author, who had just graduated from high school and started working, recalls that after a hard day's work, he would climb up to that mountain village and for some reason, his tension would ease and he would feel relaxed.

Since then, we moved every two years in the mountain village, and my mother always chose a place that wasn't too far from the turtle market.

Because I had to go there to meet someone I knew.

“It would have been nice if you had pushed me down even further since I was already at a low point.

“There were people there that I was compatible with, people I would come to love.”

When the author was diagnosed with depression and her mother's cognitive impairment, she felt guilty for having to turn away from her mother, who sat alone in a dark room.

Kim Mi-ja, who doesn't know that the person in front of her is her daughter, says that she likes nursing homes because she remembers that she was someone's mother.

It's not just because I don't have to cook, but because it's a place where there are people to build relationships with, a place where there's 'me' in addition to my mom.

The author says that the fact that her maternal grandmother, aunt, and mother all suffered from severe cognitive impairment may not be genetic, but rather “a heartbreaking legacy from the journeys they have lived.”

Discovering an individual who had been obscured by social roles directs the author's gaze to older generations of women.

Kim Mi-ja's story leads to the life of her mother, Choi Eo-jin, and her father, Kim Chang-sam's story leads to the life of his mother, Jeong Ok-saeng.

My maternal grandmother, who tried to live as a new woman, was the one who asked the author, “What is your dream in Central America?” at a time when no one asked about dreams, and my paternal grandmother, who was sold as a daughter-in-law, was like a big tree who readily prepared a meal for anyone who looked hungry.

The adults around him each lived different lives, but they all shared the experience that "even if you don't have much, sharing what you have makes you happy."

Experience becomes reality, and its repetition becomes belief, which is naturally embodied in the body and mind.

Beliefs that cannot be easily forgotten become actions, become someone's life, and change the world little by little.

The 40-year-long struggle for the poor was not a difficult but grand task for the writer.

It is a daily routine that we must learn by seeing and doing.

In his essays, the author also reveals moments when the community experienced a crisis.

When faced with each other's differences and the roots of the community are shaken, the author simply chooses to remain shaken.

“If Auntie goes somewhere, can’t you leave the lights on in the study room?” asked the children who had stayed on the road until night, waiting for their parents who had gone to work.

“Even when we’re out playing at night, I feel safe when the lights in the study room are on.” At those words, the author promises, “The lights in the study room will never go out, and I will wait there, just like my mom did.”

The author's journey of seeking a lower place through life rather than words itself makes us reflect on what kind of warmth and shame we should share with society.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 28, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 408 pages | 380g | 121*188*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791169814058

- ISBN10: 1169814050

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)